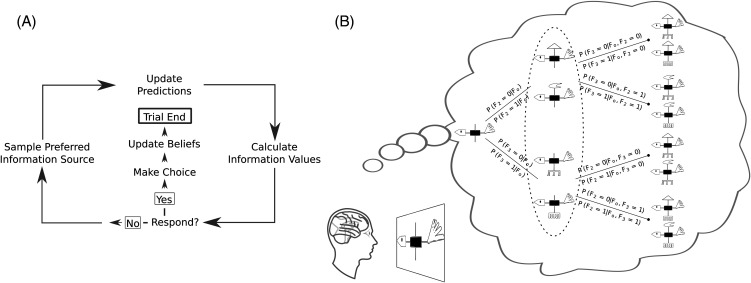

Figure 3. Active Learning and Preposterior Analysis.

Note. Active learning requires decisions, not only about the final choice but also about what information sources should be sampled. (A) When the cost of sampling an information source exceeds the expected gain in utility, a purely exploitative decision maker should commit to a final choice. (B) To decide whether to stop deliberating, or to sample an additional stimulus dimension, SEA performs preposterior analysis. In the illustrated example, two of the four features used by Rehder and Hoffman (2005a, that is, the head and tail of an abstract bird stimulus) have been observed, and all possible future sequences of samples are simulated. In typical categorization tasks, participants strive to maximize the accuracy of the final choice (as in Table 1), and the cost of sampling each dimension is equivalent. For other kinds of decisions (e.g., those involving medical diagnoses), outcomes associated with the final choice can be associated with asymmetric values (e.g., the cost of a false negative is often greater than the cost of a false positive). Similarly, different tests can impose different costs (e.g., an MRI is more expensive than a blood test). Our beliefs about costs, values, and the probabilities of future events influence what information is sampled, and therefore what is ultimately learned. Ellipse: A decision maker using a myopic planning process would consider the possible results of only a single sample into the future, and then make the best possible response. Full preposterior analysis is generally more accurate, as it also considers the potential results of subsequent samples.