Abstract

Background:

Type 2 diabetes mellitus is associated with an increased risk of developing heart failure. However, few recent studies have examined the characteristics of older adults living in US nursing homes with heart failure and diabetes mellitus. This study is important for clinical practice and public health action plans for heart failure.

Objective:

To estimate the prevalence of, and factors associated with, heart failure in long-stay nursing home residents with diabetes mellitus.

Methods:

We conducted a cross-sectional study using the US 2016 Minimum Data Set data consisting of all residents with diabetes aged ≥ 65 years in Medicare/Medicaid certified nursing homes (n=297,570). Diabetes mellitus and heart failure were operationalized using the resident’s transfer notes at admission and the progress notes during admission through physical examination findings and current treatment orders.

Results:

Among all residents with diabetes, 26.4% had heart failure. Increasing age of residents, and comorbidities including coronary artery disease (aOR: 1.34; 95% CI: 1.31–1.37), end stage renal disease (aOR: 1.30; 95% CI: 1.26–1.35), and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (aOR: 1.60; 95% CI: 1.57–1.63) were associated with a higher odds of heart failure.

Conclusions:

This is one of the first U.S studies to examine the prevalence and factors associated with heart failure in nursing home residents with diabetes mellitus. It highlights a clinically complex population with multiple comorbid conditions. Future research is needed to understand the pharmacological management of these residents and the extent to which appropriate management can improve quality of life for a medically vulnerable population.

Keywords: heart failure, epidemiology, nursing homes, aging, comorbidities, diabetes mellitus

1. INTRODUCTION

Globally, over 64 million people are afflicted with heart failure, contributing to nearly 10 million years lost due to disability (Lippi & Sanchis-Gomar, 2020). The estimated global indirect and direct expenditures on heart failure were $108 billion annually, making this condition one of the top global health and economic burdens (Cook, Cole, Asaria, Jabbour, & Francis, 2014). Heart failure is associated with increased morbidity and mortality (Butler, Fonseka, Barclay, Sembhi, & Wells, 1999; Daamen et al., 2015; Orr, Forman, De Matteis, & Gambassi, 2015), contributing to more than 250,000 deaths annually in the United States and 88% of these cases are in adults aged >65 years (Graves, 1992).

In many industrialized countries, including the United States (U.S.), heart failure is common (between 15% – 45%) among nursing home residents. Type 2 diabetes is also highly prevalent in U.S. nursing home residents (between 10–26%). Residents with Type 2 diabetes have complex care needs including regular monitoring for complications, individualized care plans, access to nutritionists, and regular monitoring of their serum glucose levels to prevent comorbidities, disability, and cognitive impairment (Bansal, Dhaliwal, & Weinstock, 2015; Sinclair, Allard, & Bayer, 1997). In older adults, overtreatment of diabetes may result in severe complications including hypoglycemia (Tseng, Soroka, Maney, Aron, & Pogach, 2014).

Although the exact pathogenesis and molecular mechanisms involved in the development of heart failure among residents living with Type 2 diabetes mellitus are unknown, there are various physiological contributors to this condition, and diabetes mellitus is a predictor of poor outcomes in patients with heart failure (Forman & Rich, 2003). The Framingham Heart Study revealed that men with diabetes mellitus had twice the risk of developing heart failure, while women with diabetes mellitus were five-times more likely to develop heart failure (Kannel & McGee, 1979). Using risk prediction models, advanced age, adiposity, blood pressure, electrocardiographic parameters, and high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol were associated with heart failure in adults with diabetes mellitus (Segar et al., 2019). To our knowledge, no studies have extensively examined the characteristics of nursing home residents with heart failure among those with Type 2 diabetes mellitus. Using a nationally representative and contemporary database, the aim of this study is to describe the frequency of, and factors associated with, heart failure in nursing home residents with diabetes mellitus. These data describe the prevalence of heart failure among nursing home residents with diabetes mellitus, and factors associated with this condition, which will assist clinicians in managing the complex needs of residents and will aid in their decision-making process.

2. METHODS

2.1. Design and Data Source

This cross-sectional study used the national 2016 Minimum Data Set Version 3.0 (MDS 3.0, 2016). The MDS is a Centers for Medicare and Medicaid tool for standardized assessment and care management for nursing home residents. It was established and implemented in all Medicare/Medicaid certified nursing homes in the US with the aim of improving the quality of care and has its roots in the Institute of Medicine Report on Nursing Home Quality of 1987 (Rahman & Applebaum, 2009). This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Massachusetts Medical School.

The MDS is conducted by trained nursing home staff on all residents at admission and discharge, in addition to other time intervals (e.g., quarterly, annually, and when residents experience a significant change in status). The sample consists of all residents in all Medicare and Medicaid Services-certified nursing homes (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, 2016).

2.2. Study Sample

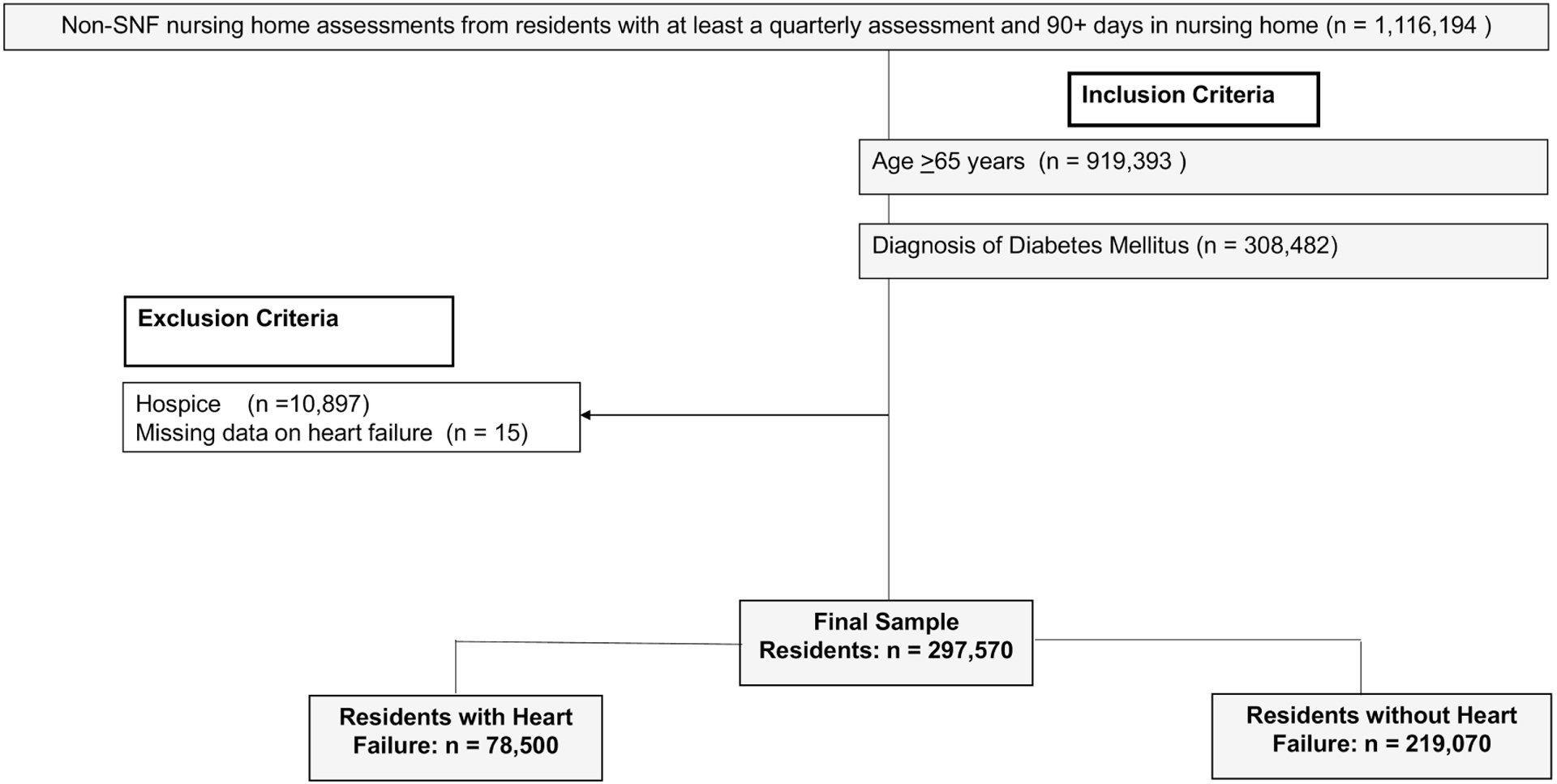

Figure 1 shows the construction of our study sample. We identified all residents with at least one quarterly assessment or annual assessment. We considered these to be long-stay nursing home residents. From these residents, we applied the following inclusion criteria: (1) age 65 years and older; and (2) documented diabetes mellitus on the MDS. At admission, nursing home staff determined the diagnosis of diabetes from the transfer notes of the resident. Also, an active diagnosis of diabetes was made for residents living in the nursing home through tests and symptoms, and this information was added to the resident’s progress notes (MDS Code: 12900). Residents were categorized as having diabetes if they were currently taking medication (e.g., insulin or other antidiabetic medication) or had some other complication for diabetes that affected their clinical care plan such as diabetic nephropathy, neuropathy and retinopathy. All these parameters were assessed on the MDS with a seven-day look-back period (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, 2016). We excluded nursing home residents receiving hospice care or who were missing data on heart failure diagnosis. The final sample consisted of 297,570 residents.

Fig. 1.

Sample selection flow chart of heart failure in nursing home residents with diabetes mellitus.

2.3. Heart Failure Diagnostic Criteria

The diagnosis of heart failure was coded by the nursing home staff using information obtained from review of transfer notes, physical examination findings, medication and other treatment orders and hospital discharge documentation in the last 60 days. The MDS manual directs staff to code a diagnosis that actively affected the resident’s care plan in the last seven days preceding the MDS assessment (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, 2016).

2.4. Covariates

Demographics variables were all obtained from the MDS assessments, and included age, sex, and race. Race was based on self-report or if the resident was unable to self-report, family (or staff if family unavailable) reported the resident’s race. We collapsed the race indicator into four categories: Non-Hispanic white, Non-Hispanic black, Hispanic, and others (American Indian / Native Alaskan / Native Hawaiian / Other Pacific Islander), due to the small number of respondents in our sample (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, 2016).

The Charlson Comorbidity Index was used as an indicator of disease burden. The Charlson Comorbidity Index predicts the risk of death within one year of hospitalization for people with 19 specific comorbid conditions. Each comorbidity has an associated weight (from 1 to 6), based on the adjusted risk of mortality or resource use, and the sum of all the weights results in a single comorbidity score for each resident. The Charlson Comorbidity Index was categorized as: 1 – 4, 5, 6 – 7, ≥8. Albeit not in the nursing home population, the higher the Charlson Comorbidity Index score, the more likely the predicted outcome will result in mortality or higher health care resource use (M. E. Charlson, Pompei, Ales, & MacKenzie, 1987).

Covariates evaluated as factors associated with heart failure included nephropathy, neurological conditions (i.e., Alzheimer’s disease, dementia, stroke), depression, hyperlipidemia, obesity, hypertension, anemia, cirrhosis, peripheral vascular disease, coronary artery disease, gastroesophageal reflux disease, pneumonia, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and cancer. Depression, dementia, and Alzheimer’s disease commonly occur in residents with heart failure which significantly contributes to cognitive decline among older adults (Doehner, 2019). Lung disease is a critical complication of heart failure, 30% of people diagnosed with pneumonia develop heart failure within 10 years (Bartlett, Ludewick, Lee, & Dwivedi, 2019) and heart failure is prevalent among adults diagnosed with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) (Lainscak et al., 2009; Ukena et al., 2010). Each of these comorbid conditions was documented on the MDS which includes a seven-day look back period from the date of assessment for active diagnosis by clinicians (as permitted by state law) at the nursing home facility. On-going medication / therapy, or a positive study, test, or procedure, are also positive indications of an active disease. The resident’s weight is regularly and consistently measured, and the nursing home residents’ most recent height (inches) and weight (pounds) measures were used to operationalize body mass index (BMI): ≤ 18.5 kg/m2, between ≥18.5 kg/m2 and ≤25 kg/m2, between >25 kg/m2 and <30 kg/m2, and BMI ≥30 kg/m2 (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, 2016).

Assessment for cognitive impairment was performed via the Cognitive Function Scale (Thomas, Dosa, Wysocki, & Mor, 2017) which combines information from the Brief Interview for Status with a seven-day look-back period and a scoring system ranging from 0 – 15 and the Cognitive Performance Scale with a score ranging from 0 – 6 (Chodosh et al., 2008). Functional status was determined from the MDS Activities of Daily Living (ADL) Self- Performance Hierarchy scale. The ADL Hierarchy Scale ranges from 0 – 6, with scores between 0 – 4 indicating physical independence, scores between 5 – 8 indicating mild dependence, scores between 9 – 12 indicating moderate dependence, and scores between 5 – 6 indicating total dependence (Morris, Fries, & Morris, 1999).

2.5. Statistical Analysis

We examined differences in the prevalence of demographic, clinical characteristics, and comorbid conditions according to the presence or absence of heart failure among residents with diabetes. We evaluated correlations and estimated variance inflation factors for the covariates to be considered in the multivariable model. Any variable whose variance inflation factor exceeded 2.5 was not included in the fully adjusted model because of multicollinearity. We constructed crude and adjusted multivariable logistic regression models with a generalized estimating equations approach to account for the clustering of residents within nursing homes. We estimated crude and adjusted odds ratios and corresponding 95% confidence intervals for all the covariates in the analysis. For the model including the Charlson Comorbidity Index, we removed the individual comorbid conditions because of multicollinearity. Further, we excluded cirrhosis and pneumonia from the fully adjusted model, and separately estimated their adjusted odds ratios with a subset of covariates included (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Association between sociodemographic, clinical characteristics and comorbid conditions and heart failure among nursing home residents living with diabetes

| Characteristics | Unadjusted Odds Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) | Full Model Odds Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years): | Reference | Reference |

| 65–74 | ||

| 75–84 | 1.12 (1.10 – 1.13) | 1.18 (1.16 – 1.19) |

| ≥85+ | 1.20 (1.18 – 1.22) | 1.30 (1.21 – 1.40) |

| Gender | Reference | Reference |

| Men | ||

| Women | 1.09 (1.08 – 1.11) | 1.03 (1.01 – 1.05) |

| Race/Ethnicity: | Reference | Reference |

| Non-Hispanic White | ||

| Non-Hispanic Black | 0.86 (0.84 – 0.87) | 0.96 (0.94 – 0.98) |

| Hispanic | 0.71 (0.69 – 0.74) | 0.85 (0.82 – 0.87) |

| American Indian / Native Alaskan / Native Hawaiian / Other Pacific Islander | 0.64 (0.61 – 0.67) | 0.81 (0.77 – 0.85) |

| Activities of daily living limitations: | ||

| Independent | 0.96 (0.95 – 0.99) | 0.96 (0.94 – 0.98) |

| Mild Dependence | Reference | Reference |

| Modified dependence | 1.02 (1.00 – 1.03) | 1.00 (0.96 – 1.06) |

| Dependent | 0.77 (0.75 – 0.79) | 1.01 (0.98 – 1.05) |

| Cognitive Impairment: | Reference | Reference |

| Intact | ||

| Mildly Impaired | 0.87 (0.85 – 0.88) | 0.98 (0.94 – 1.02) |

| Moderately Impaired | 0.69 (0.68 – 0.70) | 0.86 (0.83 – 0.89) |

| Severely Impaired | 0.52 (0.50 – 0.54) | 0.72 (0.69 – 0.74) |

| Body mass index (kg/m2): | ||

| <18.5 | 0.91 (0.87 – 0.96) | 0.92 (0.88 – 0.97) |

| 18.5 to 25.0 | Reference | Reference |

| 25 to <30 | 1.19 (1.16 – 1.21) | 1.14 (1.12 – 1.16) |

| ≥30 | 1.66 (1.64 – 1.69) | 1.40 (1.37 – 1.44) |

| Co-Morbid Conditions: | ||

| Alzheimer’s Disease | 0.78 (0.76 – 0.79) | 0.90 (0.88 – 0.92) |

| Dementia | 0.83 (0.82 – 0.84) | 0.95 (0.92 – 0.99) |

| Coronary Artery Disease | 1.64 (1.62 – 1.66) | 1.34 (1.31 – 1.37) |

| Cerebrovascular Disease | 0.93 (0.91 – 0.94) | 0.99 (0.96 – 1.03) |

| Renal Insufficiency/End Stage Renal Disease | 1.66 (1.64 – 1.69) | 1.30 (1.26 – 1.35) |

| Hypertension | 1.37 (1.33 – 1.40) | 1.19 (1.16 – 1.22) |

| Hyperlipidemia | 1.15 (1.14 – 1.17) | 1.01 (0.98 – 1.03) |

| Peripheral Vascular Disease | 1.38 (1.35 – 1.40) | 1.07 (0.99 – 1.16) |

| Anemia | 1.36 (1.35 – 1.38) | 1.15 (1.13 – 1.18) |

| Pneumonia | 1.57 (1.52 – 1.64) | 1.52 (1.46 – 1.57) |

| Depression | 1.12 (1.11 – 1.14) | 1.00 (0.95 – 1.05) |

| Cancer | 1.06 (1.03 – 1.09) | 0.98 (0.94 – 1.03) |

| Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease/Asthma | 1.92 (1.89 – 1.94) | 1.60 (1.57 – 1.63) |

| Cirrhosis | 1.20 (1.12 – 1.29) | 1.26 (1.18 – 1.35) |

| Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease /Ulcer | 1.27 (1.26 – 1.29) | 1.04 (1.01 – 1.06) |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index: | Reference | Reference |

| 1 – 4 | ||

| 5 | 1.36 (1.33 – 1.38) | 1.34 (1.31 – 1.36) |

| 6 – 7 | 1.74 (1.71 – 1.76) | 1.67 (1.64 – 1.70) |

| ≥ 8 | 1.99 (1.95 – 2.03) | 1.86 (1.83 – 1.90) |

Odds ratio estimates and corresponding 95% confidence intervals were derived from models accounting for clustering of residents within nursing homes via generalized estimating equations. Estimates for cirrhosis and pneumonia were adjusted for age, gender, race/ethnicity, activities of daily living, cognitive impairment, body mass index, Alzheimer’s disease, and dementia. Estimates for Charlson Comorbidity Index adjusted for age, sex, race/ethnicity, activities of daily living, cognitive impairment, and body mass index. All other estimates are adjusted for age, gender, race/ethnicity, activities of daily living, cognitive impairment, body mass index, and comorbidities excluding cirrhosis, pneumonia, and Charlson Comorbidity Index.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Characteristics of the Study Population

The final study sample consisted of 297,570 long stay residents in more than 15,000 nursing homes in the United States. Overall, the prevalence of heart failure was 26.4% in residents with diabetes. Approximately two-thirds were women, and the majority (70.2%) of the residents were of non-Hispanic white ethnicity (Table 1). Overall, 87.7% had a diagnosis of hypertension, 58.8% had hyperlipidemia, 53.9% reported depression, 40.3% had a BMI ≥30 kg/m2, 39.9% had gastroesophageal reflux disease or an ulcer, 58.5 % had moderate or total dependence on nursing home staff for their activities of daily living, 40.1% had moderate or severe cognitive impairment, and 31.2% had a Charlson Comorbidity Score ≥6.

Table 1:

Characteristics of Long Stay Residents with Diabetes Mellitus living in US nursing homes in 2016 (N = 297,570)

| Characteristics | Total n = 297,570 |

|---|---|

| Percentage | |

| Age category (years): | |

| 65–74 | 28.9 |

| 75–84 | 35.9 |

| ≥85 | 35.3 |

| Women | 65.6 |

| Race/Ethnicity: | |

| Non-Hispanic White | 70.2 |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 18.4 |

| Hispanic | 7.8 |

| American Indian/Native Alaskan or Hawaiian/Pacific Islander | 3.6 |

| Activities of daily living limitations: | |

| Independent | 15.0 |

| Mild dependence | 26.6 |

| Moderate dependence | 43.9 |

| Total Dependence | 14.6 |

| Cognitive Impairment: | |

| Cognitively Intact | 35.4 |

| Mildly Impaired | 24.5 |

| Moderately Impaired | 31.0 |

| Severely Impaired | 9.1 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2): | |

| <18.5 | 2.7 |

| 18.5 to 25 | 26.8 |

| 25 to <30 | 30.2 |

| ≥30 | 40.3 |

| Co-Morbid Conditions | |

| Alzheimer’s Disease | 14.0 |

| Other dementia | 45.5 |

| Coronary Artery Disease | 25.1 |

| Cerebrovascular Disease | 14.0 |

| Renal Insufficiency / End Stage Renal Disease | 18.5 |

| Hypertension | 87.7 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 58.8 |

| Peripheral Vascular Disease | 15.8 |

| Anemia | 33.4 |

| Pneumonia | 1.5 |

| Depression | 53.9 |

| Cancer | 5.3 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease/asthma | 24.9 |

| Cirrhosis | 0.6 |

| Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease/ Ulcer | 39.9 |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index: | |

| 1–4 | 51.4 |

| 5 | 17.4 |

| 6–7 | 19.7 |

| ≥ 8 | 11.5 |

Missing Data on Race/ethnicity: n=4,084; Activities of Daily Living: n=89; Body mass index n=3,340; Comorbidity index n=1,977; Alzheimer’s Disease: n=17, Other dementia n=4,402; Coronary artery disease: n=4,169, End stage renal disease n=4,167; Cancer n=4,185; Cirrhosis n=4,152; Stroke: n=11; Hypertension: n=13; Hyperlipidemia: n=17; Peripheral vascular disease: n=5; Anemia: n=17; Pneumonia: n=12; Depression: n=17; Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease/asthma: n=11, Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease/ Ulcer: n=4,181.

Table 2 shows the prevalence of heart failure according to various characteristics of the NH residents. The prevalence of heart failure increased with advancing age. Among women, 27.2% had heart failure and in men, 24.8% had heart failure. Twenty-eight percent of non-Hispanic White residents had heart failure, whereas 24.1% of non-Hispanic Black residents and one in five Hispanic residents had heart failure. Eighteen percent of American Indians/Native Alaskan or Native Hawaiian, or Other Pacific Islanders had heart failure. The prevalence of heart failure was inversely associated with activities of daily living and with cognitive impairment. The prevalence of heart failure ranged from 20.1% among those whose Charlson comorbidity index was 1 to 4 to 39.8% in those whose Charlson comorbidity index was ≥9. The prevalence of heart failure was highest among residents with pneumonia and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Table 2:

Prevalence of Heart Failure by Characteristics of Long Stay Residents with Diabetes Mellitus Living in US Nursing Homes in 2016

| Characteristics | Heart Failure Prevalence % |

|---|---|

| Age category (years): | |

| 65–74 | 23.7 |

| 75–84 | 26.4 |

| ≥85 | 28.5 |

| Women | 27.2 |

| Men | 24.8 |

| Race/Ethnicity: | |

| Non-Hispanic White | 28.2 |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 24.1 |

| Hispanic | 20.1 |

| American Indian/Native Alaskan/Native Hawaiian / Pacific Islander |

18.0 |

| Activities of daily living limitations: | |

| Independent | 26.2 |

| Mild dependence | 27.3 |

| Moderate dependence | 27.7 |

| Total Dependence | 21.0 |

| Cognitive Impairment: | |

| Cognitively Intact | 31.9 |

| Mildly Impaired | 27.7 |

| Moderately Impaired | 22.0 |

| Severely Impaired | 16.7 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2): | |

| <18.5 | 18.2 |

| 18.5 to 25.0 | 20.0 |

| 25 to <30 | 23.7 |

| >30 | 33.3 |

| Co-Morbid Conditions | |

| Alzheimer’s Disease | 21.4 |

| Other dementia | 23.9 |

| Coronary Artery Disease | 37.3 |

| Cerebrovascular Disease | 24.9 |

| Renal Insufficiency / End Stage Renal Disease | 39.1 |

| Hypertension | 27.4 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 28.0 |

| Peripheral Vascular Disease | 34.6 |

| Anemia | 32.2 |

| Pneumonia | 41.1 |

| Depression | 27.9 |

| Cancer | 28.0 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease/asthma | 41.4 |

| Cirrhosis | 31.4 |

| Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease/ Ulcer | 30.4 |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index: | |

| 1 – 4 | 20.1 |

| 5 | 27.2 |

| 6 – 7 | 34.7 |

| > 8 | 39.8 |

Missing Data on Race/ethnicity: n=4,084; Activities of Daily Living: n=89; Body mass index n=3,340; Comorbidity index n=1,977; Alzheimer’s Disease: n=17, Other dementia n=4,402; Coronary artery disease: n=4,169, End stage renal disease n=4,167; Cancer n=4,185; Cirrhosis n=4,152; Stroke: n=11; Hypertension: n=13; Hyperlipidemia: n=17; Peripheral vascular disease: n=5; Anemia: n=17; Pneumonia: n=12; Depression: n=17; Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease/asthma: n=11, Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease/ Ulcer: n=4,181.

3.2. Factors Associated with Heart Failure in Nursing Home Residents with Diabetes

Compared with residents who are between 65 – 74 years, residents aged 75 – 84 years had 1.18 times the odds of heart failure (95% CI 1.16 – 1.19), and residents aged 85 years and older had 1.30 times the odds of heart failure (95% CI 1.21 – 1.40).(Table 3) While women had slightly higher odds of heart failure relative to men (aOR: 1.03; 95% CI: 1.01–1.05), racial/ethnic minorities had lower odds relative to non-Hispanic Whites (e.g., Hispanic aOR: 0.85; 95% CI: 0.82 – 0.87). Residents with increased cognitive impairment were less likely to have heart failure relative to cognitively intact residents (e.g., severe cognitive impairment aOR: 0.72; 95% CI: 0.69–074). Relative to residents with a BMI of 18.5 to 25 kg/m2, residents with BMI 25 – 30 kg/m2 (aOR: 1.14; 95% CI: 1.12 – 1.16) and ≥30 kg/m2 (aOR: 1.40; 95% CI: 1.37 – 1.44) had a higher odds of heart failure.

The prevalence of heart failure was higher among those with coronary artery disease, end stage renal disease, hypertension, anemia, cirrhosis, GERD, and those with lung problems such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease/asthma and pneumonia (Table 3). Residents with coronary artery disease had a 34% higher odds of heart failure, compared to those without coronary artery disease, while those with end stage renal disease and hypertension had 1.30 times the odds (95% CI 1.26 – 1.35) and 1.19 times the odds (95% CI 1.16 – 1.22) respectively of heart failure, compared to those without these conditions. Residents with pneumonia and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease were at increased odds for HF compared to those without these comorbid conditions. The odds of heart failure increased with a higher CCI score from 34% higher odds in the residents with a CCI of 5 to 67% higher odds in those with CCI 6–7 and 86% higher odds in those with CCI of ≥8 relative to residents with a CCI of 1–4.

4. DISCUSSION

Nursing home residents with diabetes and heart failure are a clinically complex population. Heart failure and diabetes mellitus are often managed concurrently, collaboratively between the cardiologist, nephrologist, endocrinologist, and resident to improve symptomatology, reduce hospitalizations, and improve patient’s overall survival (Joseph, Palardy, & Bhave, 2020; Schefold, Filippatos, Hasenfuss, Anker, & von Haehling, 2016). Different morphologic and physiologic contributors to heart failure in older adults have been identified, such as vascular changes from stiffening caused by collagen / calcifications, myocardial changes from afterload pressures, apoptosis, and related hypertrophy leading to stiffness of the ventricular walls, and age-related autonomic changes (Forman & Rich, 2003). For this reason, it is important to evaluate factors associated with heart failure in nursing home residents.

In this study of nursing home residents with diabetes in the United States, we found that approximately 1 in four residents had heart failure, there was a high prevalence among women, Non-Hispanic Whites, and increasing age was associated with an increase in heart failure. This is consistent with existing literature as in older adults that have reported increased risks of heart failure with age, among women and within the Non-Hispanic White population (Ahluwalia et al., 2011; Berthelot, Nouhaud, Lafuente-Lafuente, Assayag, & Hittinger, 2019; Yang et al., 2019). In the Framingham Heart Study, the age categories were younger (45 – 74 years), but a similar trend of increasing prevalence of heart failure by age was observed (Kannel & McGee, 1979). In 2016, there were 5.1 million cases of heart failure of whom 52.9% were men (Mozaffarian et al., 2016). In our study among nursing home residents, the prevalence of heart failure in women was slightly higher than in men. After adjusting for multiple factors including other sociodemographic and clinical conditions, this gender difference remained (albeit the effect size was modest). Our findings are aligned with those from the Framingham Heart Study which reported that women had a higher risk for heart failure than men after adjustment for other associated factors (Kannel & McGee, 1979).

The majority of our population was cognitively intact, but residents with increased cognitive impairment had lower odds of having heart failure compared to cognitively intact residents. Little is known about the association between Alzheimer’s disease / dementia and heart failure, but the existing literature suggests that there may be a reduced risk for heart attacks among those taking Alzheimer’s disease medications (i.e., cholinesterase inhibitors such as donepezil, rivastigmine and galantamine), because of their anti-inflammatory properties and control over heart rate. Therefore, this lower odds of heart failure among those with moderate to severe cognitive impairment might be due to their medication regimen which protects against cardiovascular disease (Nordström P et al., 2013). Alternatively, residents with cognitive impairment may be otherwise healthier than other residents admitted to nursing homes. The overall prevalence of activities of daily living was evenly distributed among independence, mild, moderate and total dependence in our study sample, but after adjusting for sociodemographic characteristics and comorbidities, there was little to no association between activities of daily living and heart failure.

Our results showed a high prevalence of heart failure among those who had chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, pneumonia, coronary artery disease, renal insufficiency/end stage renal disease, hypertension and peripheral vascular disease. These results are consistent with a previous study examining heart failure in U.S nursing home residents using the Minimum Data Set 3.0 cross-linked to Medicare data (2011–2012), which found a high prevalence of heart failure among women, older adults, and those who have comorbid conditions including obesity, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, coronary artery disease and hypertension (Li et al., 2018).

We found that many co-morbid conditions were associated with heart failure including coronary artery disease, renal insufficiency/end stage renal disease, hypertension, anemia, pneumonia, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, cirrhosis, gastroesophageal reflux disease, and obesity, while Alzheimer’s disease/dementia, cognitive impairment, cerebrovascular disease/stroke, cancer, or being underweight were associated with a decrease in heart failure prevalence. Other findings in our study were consistent with previous studies as evidenced by comorbid conditions such as hypertension, coronary artery disease, and obesity being significant risk factors for heart failure (Ahluwalia et al., 2011; Franklin et al., 2004; Kannel & McGee, 1979; Li et al., 2018).

4.1. Clinical Implications

In both the crude and multivariable adjusted models, there was an increasing odds of heart failure seen in those with a higher Charlson Comorbidity Index, and the clinical complexity of residents with heart failure and diabetes may impact survival. In a similar study conducted among older adults in the Netherlands, the odds of mortality increased in those with heart failure and Charlson Comorbidity Index was the strongest independent predictor of mortality (Oudejans, Mosterd, Zuithoff, & Hoes, 2012). Another study conducted in the U.S showed that the Charlson Comorbidity Index was one of the factors with the most prediction power for 30-days mortality or rehospitalizations among nursing home residents with heart failure (Li et al., 2019). The extent to which the appropriate pharmacological management of nursing home residents with co-morbid heart failure and diabetes improves survival in nursing home residents warrants further exploration.

Pharmacological management of heart failure and diabetes mellitus can influence resident outcomes. According to the American Diabetes Association (ADA), the recommended first-line pharmacotherapy for heart failure in those who have diabetes mellitus are the renin-angiotensin system (RAS) inhibitors (i.e., angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACE inhibitors), angiotensin-receptor blockers (ARBs), direct renin inhibitors and/or beta-blockers (Association, 2021a; Kenny & Abel, 2019; Ponikowski et al., 2016; Yancy et al., 2016), while the recommended pharmacotherapy for diabetes mellitus in those who have heart failure are the sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitor (SGLT2) or glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist, because of their cardiovascular benefits (Association, 2021b). In addition, heart failure, diabetes mellitus and a comorbidity such as end stage renal disease usually coexist, and management of these diseases is complex. Clinicians often start with very low dosages of the renin-angiotensin system (RAS) inhibitors with close monitoring of estimated glomerular filtration rate and serum potassium, to avoid the risks of hypertension and hyperkalemia, leading to frequent fluid imbalance and requiring volume management strategies (Rangaswami & McCullough, 2018). Furthermore, depression is a common side effect of using beta blockers for management of heart failure (Patten & Lavorato, 2001).

4.2. Study Strengths and Limitations

With regards to the strengths of this study, we used a nationally representative dataset with virtually all residents of all Medicare/Medicaid certified nursing homes in the US (~98% of all homes). Missing data were minimal. Another strength was the utilization of the Charlson Comorbidity Index to determine the risk of death within one-year of hospitalization with specific comorbid conditions (M. E. Charlson et al., 1987). This summary measure is also useful to prospectively identify residents who will incur high future healthcare costs (M. Charlson, Wells, Ullman, King, & Shmukler, 2014).

There are several limitations recognized in our study. We did not have a measure for left ventricular function, which can be helpful to determine the forms of heart failure commonly experienced (i.e., systolic, or diastolic) (Paulus et al., 2007). We did not examine other covariates such as lab values, positive family history of heart failure, health behaviors, and individual genetic predisposition to heart failure in the study as these factors were not in the data source used. We recognized that our heart failure prevalence estimates in men and women derived from a cross-sectional study design may have been biased due to selective survival because men die sooner than women with increasing age.

In summary, nursing home residents with heart failure and diabetes mellitus represent a clinically challenging group to manage as evidenced by the application of the CCI in this study. There is a need to conduct future research to inform the scientific community about the influence of pharmacotherapy on our results and determine the severity of heart failure in nursing home residents using the New York Heart Staging by the American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association. This will give further guidance to clinicians about the complex treatment of heart failure in the presence of comorbid conditions.

Highlights.

In U.S nursing homes, the prevalence of heart failure increases with advancing age

Factors associated with heart failure includes pneumonia, obesity, CAD, hypertension

Older adults with pneumonia and COPD had the highest odds for heart failure

Those with a higher comorbidity index have an increased odd of one-year mortality

Heart failure with comorbid conditions require multidisciplinary care approach

Funding

This study was funded by National Institutes of Health grants to Dr. Lapane (R01NR016977) and Dr. Nunes (R21NR019160).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Ahluwalia SC, Gross CP, Chaudhry SI, Leo-Summers L, Van Ness PH, & Fried TR (2011). Change in comorbidity prevalence with advancing age among persons with heart failure. Journal of general internal medicine, 26(10), 1145–1151. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21573881 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3181289/. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1725-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Association AD (2021a). 10. Cardiovascular Disease and Risk Management: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes—2021. Diabetes Care, 44(Supplement 1), S125–S150. Retrieved from https://care.diabetesjournals.org/content/diacare/44/Supplement_1/S125.full.pdf. doi: 10.2337/dc21-S010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Association AD (2021b). 11. Microvascular Complications and Foot Care: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes—2021. Diabetes Care, 44(Supplement 1), S151–S167. Retrieved from https://care.diabetesjournals.org/content/diacare/44/Supplement_1/S151.full.pdf. doi: 10.2337/dc21-S011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bansal N, Dhaliwal R, & Weinstock RS (2015). Management of Diabetes in the Elderly. Medical Clinics of North America, 99(2), 351–377. Retrieved from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0025712514001989. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2014.11.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartlett B, Ludewick HP, Lee S, & Dwivedi G (2019). Cardiovascular complications following pneumonia: focus on pneumococcus and heart failure. Curr Opin Cardiol, 34(2), 233–239. doi: 10.1097/hco.0000000000000604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berthelot E, Nouhaud C, Lafuente-Lafuente C, Assayag P, & Hittinger L (2019). [Heart failure in patients over 80 years old]. Presse Med, 48(2), 143–153. doi: 10.1016/j.lpm.2019.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler R, Fonseka S, Barclay L, Sembhi S, & Wells S (1999). The health of elderly residents in long term care institutions in New Zealand. N Z Med J, 112(1099), 427–429. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. (2016). Long-Term Care Facility Resident Assessment Instrument 3.0 User’s Manual.

- Charlson M, Wells MT, Ullman R, King F, & Shmukler C (2014). The Charlson comorbidity index can be used prospectively to identify patients who will incur high future costs. PLoS One, 9(12), e112479. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0112479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, & MacKenzie CR (1987). A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis, 40(5), 373–383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chodosh J, Edelen MO, Buchanan JL, Yosef JA, Ouslander JG, Berlowitz DR, … Saliba D (2008). Nursing home assessment of cognitive impairment: development and testing of a brief instrument of mental status. J Am Geriatr Soc, 56(11), 2069–2075. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01944.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook C, Cole G, Asaria P, Jabbour R, & Francis DP (2014). The annual global economic burden of heart failure. Int J Cardiol, 171(3), 368–376. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2013.12.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daamen MAMJ, Hamers JPH, Gorgels APM, Brunner-La Rocca H-P, Tan FES, van Dieijen-Visser MP, & Schols JMGA (2015). Heart failure in nursing home residents; a cross-sectional study to determine the prevalence and clinical characteristics. BMC Geriatrics, 15(1), 167. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-015-0166-1. doi: 10.1186/s12877-015-0166-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doehner W (2019). Dementia and the heart failure patient. European Heart Journal Supplements, 21(Supplement_L), L28–L31. Retrieved from 10.1093/eurheartj/suz242. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/suz242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forman DE, & Rich MW (2003). Heart Failure in the Elderly. Congestive Heart Failure, 9(6), 311–323. Retrieved from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1527-5299.2003.00798.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1527-5299.2003.00798.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin K, Goldberg RJ, Spencer F, Klein W, Budaj A, Brieger D, … Gore JM (2004). Implications of diabetes in patients with acute coronary syndromes. The Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events. Arch Intern Med, 164(13), 1457–1463. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.13.1457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graves EJ (1992). Detailed diagnoses and procedures, national hospital discharge survey, 1990. Vital Health Stat 13(113), 1–225. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joseph MS, Palardy M, & Bhave NM (2020). Management of heart failure in patients with end-stage kidney disease on maintenance dialysis: a practical guide. Rev Cardiovasc Med, 21(1), 31–39. doi: 10.31083/j.rcm.2020.01.24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kannel WB, & McGee DL (1979). Diabetes and cardiovascular disease. The Framingham study. Jama, 241(19), 2035–2038. doi: 10.1001/jama.241.19.2035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenny HC, & Abel ED (2019). Heart Failure in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Circulation Research, 124(1), 121–141. Retrieved from https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/abs/10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.118.311371. doi:doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.118.311371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lainscak M, Hodoscek LM, Düngen HD, Rauchhaus M, Doehner W, Anker SD, & von Haehling S (2009). The burden of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in patients hospitalized with heart failure. Wien Klin Wochenschr, 121(9–10), 309–313. doi: 10.1007/s00508-009-1185-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Baek J, Jesdale BM, Hume AL, Gambassi G, Goldberg RJ, & Lapane KL (2019). Predicting 30-day mortality and 30-day re-hospitalization risks in Medicare patients with heart failure discharged to skilled nursing facilities: development and validation of models using administrative data. J Nurs Home Res Sci, 5, 60–67. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Jesdale BM, Hume A, Gambassi G, Goldberg RJ, & Lapane KL (2018). Who are they? Patients with heart failure in American skilled nursing facilities. J Cardiol, 71(4), 428–434. doi: 10.1016/j.jjcc.2017.09.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lippi G, & Sanchis-Gomar F (2020). Global epidemiology and future trends of heart failure. AME Medical Journal, 5. Retrieved from https://amj.amegroups.com/article/view/5475. [Google Scholar]

- Morris JN, Fries BE, & Morris SA (1999). Scaling ADLs within the MDS. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci, 54(11), M546–553. doi: 10.1093/gerona/54.11.m546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, Go AS, Arnett DK, Blaha MJ, Cushman M, … Turner MB (2016). Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics—2016 Update. Circulation, 133(4), e38–e360. Retrieved from https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/abs/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000350. doi:doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nordström P, Religa D, Wimo A, Winblad B, Eriksdotter M. (2013). The use of cholinesterase inhibitors and the risk of myocardial infarction and death: a nationwide cohort study in subjects with Alzheimer’s disease, European Heart Journal, Volume 34, Issue 33, Pages 2585–2591, 10.1093/eurheartj/eht182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orr NM, Forman DE, De Matteis G, & Gambassi G (2015). Heart Failure Among Older Adults in Skilled Nursing Facilities: More of a Dilemma Than Many Now Realize. Current Geriatrics Reports, 4(4), 318–326. Retrieved from 10.1007/s13670-015-0150-9. doi: 10.1007/s13670-015-0150-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oudejans I, Mosterd A, Zuithoff NP, & Hoes AW (2012). Comorbidity Drives Mortality in Newly Diagnosed Heart Failure: A Study Among Geriatric Outpatients. Journal of Cardiac Failure, 18(1), 47–52. Retrieved from 10.1016/j.cardfail.2011.10.009. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2011.10.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patten SB, & Lavorato DH (2001). Medication use and major depressive syndrome in a community population. Compr Psychiatry, 42(2), 124–131. doi: 10.1053/comp.2001.21218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulus WJ, Tschöpe C, Sanderson JE, Rusconi C, Flachskampf FA, Rademakers FE, … Brutsaert DL (2007). How to diagnose diastolic heart failure: a consensus statement on the diagnosis of heart failure with normal left ventricular ejection fraction by the Heart Failure and Echocardiography Associations of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J, 28(20), 2539–2550. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehm037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponikowski P, Voors AA, Anker SD, Bueno H, Cleland JG, Coats AJ, … van der Meer P (2016). 2016 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: The Task Force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Developed with the special contribution of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur J Heart Fail, 18(8), 891–975. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahman AN, & Applebaum RA (2009). The Nursing Home Minimum Data Set Assessment Instrument: Manifest Functions and Unintended Consequences—Past, Present, and Future. The Gerontologist, 49(6), 727–735. Retrieved from 10.1093/geront/gnp066. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnp066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rangaswami J, & McCullough PA (2018). Heart Failure in End-Stage Kidney Disease: Pathophysiology, Diagnosis, and Therapeutic Strategies. Seminars in Nephrology, 38(6), 600–617. Retrieved from 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2018.08.005. doi: 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2018.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schefold JC, Filippatos G, Hasenfuss G, Anker SD, & von Haehling S (2016). Heart failure and kidney dysfunction: epidemiology, mechanisms and management. Nat Rev Nephrol, 12(10), 610–623. Retrieved from http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/27573728 https://doi.org/10.1038/nrneph.2016.113. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2016.113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segar MW, Vaduganathan M, Patel KV, McGuire DK, Butler J, Fonarow GC, … Pandey A (2019). Machine Learning to Predict the Risk of Incident Heart Failure Hospitalization Among Patients With Diabetes: The WATCH-DM Risk Score. Diabetes Care, 42(12), 2298. Retrieved from http://care.diabetesjournals.org/content/42/12/2298.abstract. doi: 10.2337/dc19-0587 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinclair AJ, Allard I, & Bayer A (1997). Observations of diabetes care in long-term institutional settings with measures of cognitive function and dependency. Diabetes Care, 20(5), 778–784. doi: 10.2337/diacare.20.5.778 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas KS, Dosa D, Wysocki A, & Mor V (2017). The Minimum Data Set 3.0 Cognitive Function Scale. Med Care, 55(9), e68–e72. doi: 10.1097/mlr.0000000000000334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tseng C-L, Soroka O, Maney M, Aron DC, & Pogach LM (2014). Assessing Potential Glycemic Overtreatment in Persons at Hypoglycemic Risk. JAMA Internal Medicine, 174(2), 259–268. Retrieved from 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.12963. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.12963 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ukena C, Mahfoud F, Kindermann M, Kindermann I, Bals R, Voors AA, … Böhm M (2010). The cardiopulmonary continuum systemic inflammation as ‘common soil’ of heart and lung disease. Int J Cardiol, 145(2), 172–176. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2010.04.082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, Butler J, Casey DE Jr., Colvin MM, … Westlake C (2016). 2016 ACC/AHA/HFSA Focused Update on New Pharmacological Therapy for Heart Failure: An Update of the 2013 ACCF/AHA Guideline for the Management of Heart Failure: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Failure Society of America. J Am Coll Cardiol, 68(13), 1476–1488. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.05.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang M-X, An H, Fan X-Q, Tao L-Y, Tu Q, Qin L, … Ren J-Y (2019). Age-specific differences in non-cardiac comorbidities among elderly patients hospitalized with heart failure: a special focus on young-old, old-old, and oldest-old. Chinese medical journal, 132(24), 2905–2913. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31809320 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6964950/. doi: 10.1097/CM9.0000000000000560 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]