Abstract

Introduction

Guselkumab is approved for the treatment of both moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis and active psoriatic arthritis (PsA) in the USA. However, little is known about patients initiating guselkumab in a real-world setting. The objective of this study was to describe baseline characteristics among patients with plaque psoriasis who initiated guselkumab at or after enrollment in CorEvitas’ Psoriasis Registry.

Methods

Adult patients who initiated guselkumab in the Psoriasis Registry between July 18, 2017 and November 6, 2018 were included. Demographics, disease characteristics, and patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) were assessed at the time of guselkumab initiation (baseline). Patients with psoriasis were stratified according to the number of previously received biologics (0 to 4+) for comparison. A subset of patients with psoriasis and concomitant dermatologist-diagnosed PsA were stratified into biologic-naïve and biologic-experienced groups.

Results

Among 687 patients with psoriasis who initiated guselkumab, biologic-naïve patients and those with four or more prior biologics had the most severe disease and the worst PROM scores at baseline. Among 251 patients with concomitant dermatologist-diagnosed PsA, biologic-naïve patients had more severe disease and worse PROM scores than biologic-experienced patients.

Conclusions

These findings highlight important differences in baseline characteristics according to biologic experience among patients with plaque psoriasis with or without concomitant PsA initiating guselkumab in a real-world setting.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s13555-021-00637-2.

Keywords: CorEvitas’ Psoriasis Registry, Guselkumab, Patient characteristics, Psoriasis, Psoriatic arthritis, Real-world evidence

Key Summary Points

| Why carry out this study? |

| Guselkumab is an anti-interleukin-23 biologic approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of adult patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis or active psoriatic arthritis (PsA); however, characteristics of patients who initiate guselkumab in a real-world setting are not well described. |

| The objective of this study was to describe baseline demographics, disease characteristics, and patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) among patients with plaque psoriasis—including a subset of patients with concomitant dermatologist-diagnosed PsA—who initiated guselkumab in CorEvitas’ Psoriasis Registry. |

| What was learned from the study? |

| After patients with psoriasis were stratified according to the number of previously received biologics for comparison, biologic-naïve patients and those with the greatest previous exposure to biologics (4+ prior biologics) had the most severe disease and the worst PROM scores at baseline. |

| Among patients with psoriasis and concomitant dermatologist-diagnosed PsA, biologic-naïve patients had more severe disease and worse PROM scores than biologic-experienced patients. |

| This study is among the first to describe characteristics of patients with psoriasis with or without concomitant PsA initiating treatment with guselkumab in the real world, and the findings show important differences in baseline demographics, disease characteristics, and PROMs according to previous experience with biologic therapy. |

Introduction

Psoriasis is a chronic, immune-mediated dermatologic disease characterized by inflammatory skin lesions that result in pain, itching, and scaling [1–3]. In the USA, the disease has a prevalence of approximately 3.2% and affects more than 7.4 million individuals [4]. Psoriasis is associated with a substantial impact on the physical and psychological well-being of patients, and often results in reduced quality of life (QoL) [5–8]. Approximately 25–30% of patients with psoriasis also have concomitant psoriatic arthritis (PsA), a chronic, immune-mediated inflammatory disease characterized by peripheral arthritis, enthesitis, dactylitis, axial disease, and skin and nail lesions associated with psoriasis [9–11]. The high clinical and humanistic burden of psoriasis is commonly exacerbated by concomitant PsA, as well as comorbidities such as anxiety, depression, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, and cancer [9, 12–16].

Biologic therapies targeting inflammatory cytokines have become a key component of treatment for moderate-to-severe psoriasis [10, 17–19]. The first biologics used for the disease included tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors (i.e., adalimumab, etanercept, and infliximab) and the interleukin (IL)-12/23 inhibitor ustekinumab [3, 10, 18]. However, research over the last decade has established critical roles for IL-17 and IL-23 in the pathogenesis of psoriasis, and the focus has shifted to developing therapies that target these cytokines [18, 20–22]. Current US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved biologics that inhibit IL-17 include brodalumab, ixekizumab, and secukinumab, while those targeting IL-23 include guselkumab, risankizumab, and tildrakizumab [3, 18, 23].

Guselkumab (Janssen Biotech, Inc., Horsham, PA, USA) is a fully human monoclonal antibody that binds to the p19 subunit of IL-23, inhibiting its intracellular and downstream signaling [2, 24, 25]. Guselkumab was approved by the FDA in July 2017 [24] for the treatment of adult patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis on the basis of results from two phase III clinical trials: VOYAGE 1 (NCT02207231) [2] and VOYAGE 2 (NCT02207244) [25]. Both trials assessed the efficacy and safety of guselkumab compared with placebo and with the TNF antagonist adalimumab in patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis, and included an open-label extension phase through 5 years [26, 27]. Guselkumab also received FDA approval for the treatment of adult patients with active PsA [24] in July 2020 on the basis of results from the two phase III clinical trials DISCOVER-1 (NCT03162796) [28] and DISCOVER-2 (NCT03158285) [29].

Patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis may receive several different successive biologic agents over the course of their disease [17, 30–34], and prior exposure to biologics may impact the response to subsequent therapies [35–37]. In addition, patient- and disease-related characteristics may differ between biologic-naïve and biologic-experienced patients [35–37]. Patients with PsA may also be exposed to multiple biologics over the course of their disease [38–40]; evidence is mixed regarding the impact of biologic experience on outcomes with subsequent therapies in these patients [38–41].

Assessments of real-world data can provide important insights into potential differences in patient- and disease-related characteristics at the time of new treatment initiation. As noted above, such differences may impact response to treatment [35–37]. The baseline characteristics of patients initiating treatment with guselkumab in the real world are not well described. The objective of this study was to describe baseline demographics, disease characteristics, treatment history, and patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) among patients with psoriasis who initiated guselkumab in CorEvitas’ Psoriasis Registry. These outcomes were also examined in a subset of patients with psoriasis and concomitant dermatologist-diagnosed PsA.

Methods

Patient Population

CorEvitas’ Psoriasis Registry is an independent, prospective, multicenter, observational, North American registry that was launched in April 2015 in collaboration with the National Psoriasis Foundation (NPF) [3, 42–44]. Participating physicians may enroll eligible patients aged at least 18 years old who have been diagnosed with psoriasis by a dermatologist and who initiated an eligible medication at enrollment (incident user) or within the previous 12 months before enrollment (prevalent user). Medications deemed eligible for patients to be enrolled in the registry include biologic therapies and nonbiologic systemic medications that are approved by the FDA for the treatment of psoriasis [3, 42–44]. At the time of the present analysis, this included the biologic therapies adalimumab, brodalumab, certolizumab pegol, etanercept, guselkumab, infliximab, ixekizumab, secukinumab, and ustekinumab, and the systemic nonbiologic therapies acitretin, apremilast, cyclosporine, and methotrexate.

The present study evaluated data for patients with plaque psoriasis who initiated guselkumab at or after registry enrollment (i.e., incident guselkumab users) between July 18, 2017 (immediately after the approval of guselkumab) and November 6, 2018 (most recent data cut available at the time of the analysis). Data were also analyzed for a subset of patients with both plaque psoriasis and dermatologist-diagnosed PsA who initiated guselkumab at or after registry enrollment during the same time period. Data for a smaller subset of patients who reported that their diagnosis of PsA had been confirmed by a rheumatologist are included in the Supplementary Material. Rheumatologist-confirmed PsA as reported by the patient was recorded by the residing dermatologist on the case report form.

All participating investigators were required to obtain full board approval for conducting research involving human subjects. Sponsor approval and continuing review was obtained through a central IRB (IntegReview, Protocol number is Corrona-PSO-500). For academic investigative sites that did not receive a waiver to use the central IRB, approval was obtained from the respective governing IRBs and documentation of approval was submitted to the sponsor prior to initiating any study procedures. All registry subjects were required to provide written informed consent prior to participating. This study was performed in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1964 and its later amendments.

Measures

All measures were assessed at the index date (defined as the date of first guselkumab initiation for incident users). Measures of interest included:

Demographics (age, gender, race, health insurance type, education, work status, smoking history, body weight, and body mass index [BMI])

Disease characteristics (comorbidities [reported by the physician and based on CorEvitas questionnaires], psoriasis morphology and duration, diagnosis of PsA, Psoriasis Epidemiology Screening Tool [PEST] score; body surface area [BSA] affected [0–100%], Investigator Global Assessment [IGA; 0–4], and Psoriasis Area and Severity Index [PASI; 0–72])

Treatment characteristics (concomitant therapy use, psoriasis treatment history, and reasons for initiating guselkumab)

PROMs (patient-reported itch, fatigue, and skin pain due to psoriasis; patient-reported joint pain and wellness as a result of PsA among patients with dermatologist-diagnosed PsA; Patient Global Assessment [PGA] of psoriasis; Work Productivity and Activity Impairment [WPAI] questionnaire; Dermatology Life Quality Index [DLQI] questionnaire; and EuroQoL-5 dimensions, 3 levels [EQ-5D-3L] visual analog scale [VAS] health state and categorical domains)

Patient-reported overall itch, fatigue, and skin pain due to psoriasis, PGA of psoriasis, joint pain due to PsA, and wellness as a result of PsA were measured on a VAS of 0–100, with higher scores indicating more severe symptoms or higher disease activity [3, 42]. The WPAI questionnaire was used to assess the impact of psoriasis on workplace productivity and on daily activities among currently employed individuals across the following four domains: the mean percentage of work hours missed, mean percentage of impairment while working, mean overall percentage of work hours affected, and mean percentage of daily activities impaired [3, 45]. The DLQI questionnaire was used to measure the impact of psoriasis on QoL with a composite score of 0–30, with higher scores indicating greater impact on QoL (effect on life categories: 0–1 = no effect; 2–5 = small effect; 6–10 = moderate effect; 11–20 = large effect; and 21–30 = extremely large effect) [3, 46]. Finally, the EQ-5D-3L VAS was used to measure QoL on a scale of 0–100, where 0 equates to “the worst imaginable health state” and 100 equates to the “best imaginable health state” [47]. Categorical domains of the EQ-5D-3L were reported as percentage of patients reporting at least some problem with walking, self-care, usual activities, pain and discomfort, anxiety and depression, and sleeping.

Statistical Analysis

Characteristics at the index date were calculated as mean (standard deviation [SD]) for continuous variables and frequency (percentage) of patients for categorical variables. Patients with psoriasis were stratified according to the number of previously used biologic therapies to detect whether baseline characteristics differed between these groups. For comparisons of characteristics across patients with psoriasis stratified according to the number of prior biologics received, Kruskal–Wallis tests were used to analyze continuous variables and chi-squared tests or Fisher’s exact tests were used to analyze categorical variables. Comparisons with P < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. For the subgroup of patients with psoriasis and concomitant PsA, standardized differences were used to compare all characteristics between biologic-naïve and biologic-experienced patients. Characteristics with standardized differences of greater than 0.10 were considered to differ meaningfully between groups [48]. Different approaches were used for comparisons in the main psoriasis cohort and in the subgroup of patients with concomitant PsA because of the smaller sample size in the PsA subgroup (i.e., not enough patients to stratify according to number of prior biologics).

Results

Demographics and Disease Characteristics

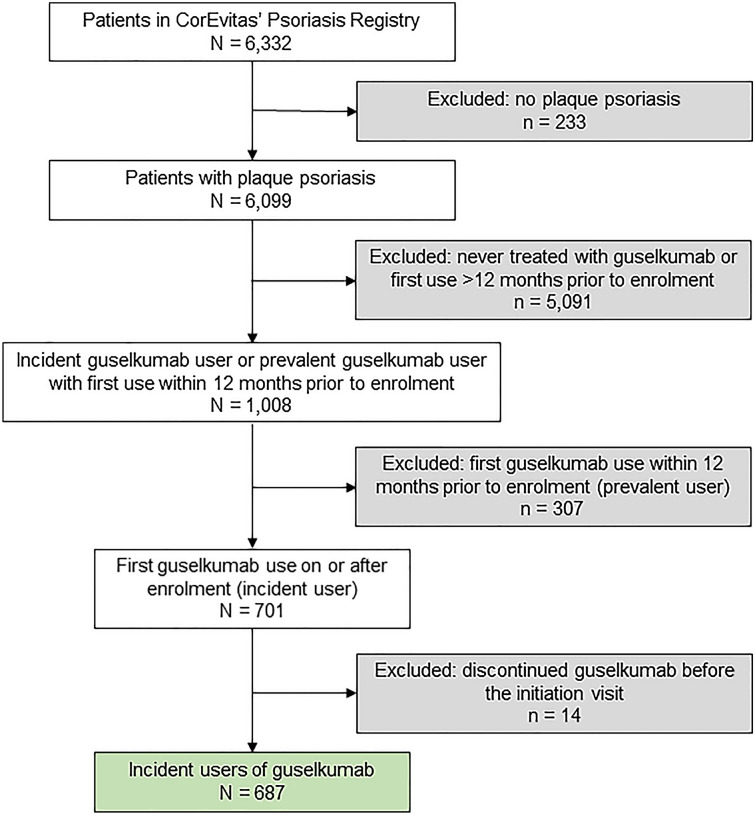

Review of CorEvitas’ Psoriasis Registry identified 687 patients with plaque psoriasis who were incident users of guselkumab during the study period (Fig. 1). The baseline demographics and disease characteristics for these patients are presented in Table 1. The mean age was 50.1 (SD 14.3) years, 48.0% of patients were female, 81.2% were white, mean body weight was 94.9 (25.5) kg, and 55.3% of patients had a BMI > 30 kg/m2. Concomitant PsA was found in 37.0% of patients with psoriasis. The mean duration of psoriasis was 16.8 (13.3) years, the mean duration of PsA was 9.3 (9.1) years, and 29.7% of patients had a PEST score ≥ 3 (indicating a risk of having PsA and warranting a rheumatology referral [49]). In terms of clinical disease severity measures, mean BSA affected was 12.6% (14.2%), mean PASI score was 8.0 (7.5), and mean IGA score was 2.8 (0.9); these mean scores indicate that, on average, patients in the study population had moderate-to-severe disease [50–52]. The majority of patients had prior experience with biologic therapy (81.5%), most of whom had previously received at least two different agents (69.5%) before initiating guselkumab (Table 1). These included IL-12/23 inhibitors, which have a partially shared mechanism of action with guselkumab (ustekinumab: 52.4% of patients); TNF inhibitors (adalimumab, etanercept, infliximab, or certolizumab pegol: 63.2% of patients); and IL-17 inhibitors (secukinumab, ixekizumab, or brodalumab: 38.9% of patients). Among patients who reported reasons for initiation of guselkumab (n = 130), the most common reason was “active disease” (88.5%).

Fig. 1.

Flow chart of study population

Table 1.

Baseline demographics and disease characteristics of patients with plaque psoriasis who initiated guselkumab in CorEvitas’ Psoriasis Registry

| Characteristicsa | Patients initiating guselkumab (N = 687) |

|---|---|

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 50.1 (14.3) |

| Female, n (%) | 329 (48.0) |

| White, n (%) | 558 (81.2) |

| Private health insurance, n (%) | 558 (81.2) |

| Some college or more, n (%) | 513 (74.9) |

| Employed full time, n (%) | 428 (62.4) |

| Current smoker, n (%) | 120 (17.7) |

| Body weight (kg), mean (SD) | 94.9 (25.5) |

| BMI > 30 kg/m2, n (%) | 379 (55.3) |

| History of comorbidities, n (%) | |

| Cancerb | 44 (6.4) |

| Serious infections | 25 (3.6) |

| Cardiovascular diseasec | 29 (4.2) |

| Hypertension | 145 (21.1) |

| Hyperlipidemia | 94 (13.7) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 43 (6.3) |

| Crohn’s disease | 5 (0.7) |

| Ulcerative colitis | 4 (0.6) |

| Depression | 69 (10.0) |

| Anxiety | 76 (11.1) |

| BSA (%), mean (SD) | 12.6 (14.2) |

| PASI (score 0–72), mean (SD) | 8.0 (7.5) |

| IGA, mean (SD) | 2.8 (0.9) |

| Psoriasis morphology | |

| Scalp | 267 (38.9) |

| Nail | 119 (17.3) |

| Palmoplantar | 93 (13.5) |

| Genital | 49 (7.1) |

| Psoriasis duration (years), mean (SD) | 16.8 (13.3) |

| PsA, n/N1 (%) | 251/678 (37.0) |

| Confirmed by rheumatologist, n/N1 (%) | 113/216 (52.3) |

| PsA duration (years), mean (SD) (n = 226) | 9.3 (9.1) |

| PEST score ≥ 3, n/N1 (%) | 202/679 (29.7) |

| Initiated guselkumab because of active disease, n/N1 (%) | 115/130 (88.5) |

| Concomitant therapy, n (%) | |

| Systemic therapyd | 106 (15.4) |

| Topical agents | 276 (40.2) |

| Biologic-experienced patientse, n (%) | 560 (81.5) |

| 1 previous biologic agent received, n (%) | 171 (30.5) |

| ≥ 2 previous biologic agents received, n (%) | 389 (69.5) |

BMI body mass index, BSA body surface area, IGA Investigator’s Global Assessment, PASI Psoriasis Area Severity Index, PEST Psoriasis Epidemiology Screening Tool, PsA psoriatic arthritis, SD standard deviation, TIA transient ischemic attack

aItem non-response was < 2% for all cells unless denominator is reported

bCancer includes lymphoma, lung, breast, skin (basal cell, squamous cell, melanoma), and any other cancers

cCardiovascular disease includes baseline history of any of the following: cardiac revascularization procedure, ventricular arrhythmia, cardiac arrest, myocardial infarction, acute coronary syndrome, unstable angina, coronary artery disease, and congestive heart failure; cerebrovascular disease includes baseline history of any of the following: stroke, TIA, peripheral vascular disease, peripheral arterial disease

dSystemic therapy includes biologics listed above and the non-biologics apremilast, cyclosporine, acitretin, and methotrexate

eBiologic medications included adalimumab, brodalumab, certolizumab pegol, etanercept, guselkumab, infliximab, ixekizumab, secukinumab, and ustekinumab

Baseline demographics and disease characteristics among incident guselkumab users were compared among patients stratified according to the number of previously received biologic therapies (Table 2). The numbers of patients (%) in each group were as follows: no prior biologics/biologic-naïve, 127 (18.5%); one prior biologic, 171 (24.9%), two prior biologics, 150 (21.8%); three prior biologics, 110 (16.0%); and four or more prior biologics, 129 (18.8%). No statistically significant differences were found among groups for most demographics, with some exceptions. Mean body weight and the proportion of patients with BMI > 30 kg/m2 were significantly different among groups (both P < 0.001); both characteristics were lowest among biologic-naïve patients and highest among those who previously received four or more biologics (Table 2).

Table 2.

Baseline demographics and disease characteristics of patients with plaque psoriasis who initiated guselkumab in CorEvitas’ Psoriasis Registry by number of prior biologics

| Characteristicsa | Number of prior biologicsb (n) | P valuec | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 (n = 127) | 1 (n = 171) | 2 (n = 150) | 3 (n = 110) | 4+ (n = 129) | ||

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 48.9 (15.9) | 49.7 (15.2) | 50.5 (12.6) | 51.1 (13.4) | 50.7 (14.1) | 0.14 |

| Female, n (%) | 61 (48.0) | 93 (54.4) | 62 (41.3) | 51 (46.8) | 62 (48.1) | 0.24 |

| White, n (%) | 105 (82.7) | 136 (79.5) | 116 (77.3) | 91 (82.7) | 110 (85.3) | 0.47 |

| Private health insurance, n (%) | 106 (83.5) | 139 (81.3) | 121 (80.7) | 88 (80.0) | 104 (80.6) | 0.96 |

| Some college or more, n (%) | 95 (75.4) | 128 (74.9) | 112 (74.7) | 87 (79.8) | 91 (70.5) | 0.61 |

| Employed full time n, (%) | 82 (64.6) | 100 (58.5) | 98 (65.3) | 69 (63.3) | 79 (61.2) | 0.73 |

| Current smoker, n (%) | 17 (13.7) | 25 (14.7) | 33 (22.3) | 16 (14.8) | 29 (22.8) | 0.11 |

| Body weight (kg), mean (SD) | 88.3 (22.7) | 91.6 (24.9) | 96.0 (27.3) | 97.8 (23.6) | 102.1 (26.5) | < 0.001 |

| BMI > 30 kg/m2, n (%) | 51 (40.5) | 85 (50.0) | 83 (55.3) | 73 (66.4) | 87 (67.4) | < 0.001 |

| History of comorbidities, n (%) | ||||||

| Cancerd | 6 (4.7) | 12 (7.0) | 12 (8.0) | 8 (7.3) | 6 (4.7) | 0.71 |

| Serious infections^ | 0 (0.0) | 8 (4.7) | 8 (5.3) | 2 (1.8) | 7 (5.4) | 0.03 |

| Cardiovascular diseasee | 7 (5.5) | 5 (2.9) | 7 (4.7) | 5 (4.5) | 5 (3.9) | 0.85 |

| Hypertension | 36 (28.3) | 36 (21.1) | 30 (20.0) | 17 (15.5) | 26 (20.2) | 0.18 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 22 (17.3) | 23 (13.5) | 19 (12.7) | 16 (14.5) | 14 (10.9) | 0.64 |

| Diabetes mellitus^ | 10 (7.9) | 8 (4.7) | 13 (8.7) | 4 (3.6) | 8 (6.2) | 0.40 |

| Crohn’s disease^ | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.6) | 2 (1.3) | 2 (1.8) | 0 (0.0) | 0.34 |

| Ulcerative colitis^ | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.3) | 1 (0.9) | 1 (0.8) | 0.46 |

| Depression | 24 (18.9) | 19 (11.1) | 8 (5.3) | 7 (6.4) | 11 (8.5) | 0.002 |

| Anxiety | 23 (18.1) | 22 (12.9) | 11 (7.3) | 9 (8.2) | 11 (8.5) | 0.03 |

| BSA (%), mean (SD) | 15.0 (13.6) | 10.3 (12.1) | 12.8 (14.4) | 10.8 (15.2) | 14.6 (15.8) | < 0.001 |

| PASI (score 0–72), mean (SD) | 8.9 (7.4) | 6.8 (7.1) | 7.6 (6.2) | 7.3 (6.8) | 9.6 (9.5) | 0.003 |

| IGA, mean (SD) | 2.9 (0.8) | 2.6 (0.9) | 2.7 (0.9) | 2.7 (0.9) | 3.0 (0.8) | 0.004 |

| Psoriasis morphology | ||||||

| Scalp | 52 (40.9) | 57 (33.3) | 54 (36.0) | 43 (39.1) | 61 (47.3) | 0.15 |

| Nail | 16 (12.6) | 20 (11.7) | 29 (19.3) | 22 (20.0) | 32 (24.8) | 0.02 |

| Palmoplantar | 14 (11.0) | 16 (9.4) | 18 (12.0) | 15 (13.6) | 30 (23.3) | 0.007 |

| Genital | 19 (15.0) | 11 (6.4) | 6 (4.0) | 5 (4.5) | 8 (6.2) | 0.004 |

| Psoriasis duration (years), mean (SD) | 10.8 (11.6) | 16.6 (14.6) | 17.8 (13.3) | 19.7 (12.0) | 19.2 (12.4) | < 0.001 |

| PsA, n/N1 (%) | 17/126 (13.5) | 49/168 (29.2) | 60/150 (40.0) | 56/109 (51.4) | 69/125 (55.2) | < 0.001 |

| Confirmed by rheumatologist, n/N1 (%) | 10/16 (62.5) | 18/38 (47.4) | 24/53 (45.3) | 24/47 (51.1) | 37/62 (59.7) | 0.48 |

| PsA duration (years), mean (SD) |

n = 16 10.5 (15.4) |

n = 45 6.2 (8.4) |

n = 55 8.0 (8.3) |

n = 53 11.6 (9.1) |

n = 57 10.7 (7.3) |

< 0.001 |

| PEST score ≥ 3, n/N1 (%) |

24/126 (19.0) |

36/170 (21.2) |

49/146 (33.6) |

36/110 (32.7) |

57/127 (44.9) |

< 0.001 |

| Concomitant therapy, n (%) | ||||||

| Systemic therapyf | 10 (7.9) | 20 (11.7) | 26 (17.3) | 24 (21.8) | 26 (20.2) | 0.009 |

| Topical agents | 66 (52.0) | 61 (35.7) | 60 (40.0) | 46 (41.8) | 43 (33.3) | 0.02 |

BMI body mass index, BSA body surface area, IGA Investigator’s Global Assessment, PASI Psoriasis Area Severity Index, PEST Psoriasis Epidemiology Screening Tool, PsA psoriatic arthritis, SD standard deviation, TIA transient ischemic attack

aItem non-response was < 3% for all cells unless denominator is reported

bBiologic medications included adalimumab, brodalumab, certolizumab pegol, etanercept, guselkumab, infliximab, ixekizumab, secukinumab, and ustekinumab

cKruskal–Wallis tests for continuous variables and χ2 tests or Fisher’s exact tests (denoted with ^) for categorical variables. Statistically significant differences (P < 0.05) are bolded

dCancer includes lymphoma, lung, breast, skin (basal cell, squamous cell, melanoma), and any other cancers

eCardiovascular disease includes baseline history of any of the following: cardiac revascularization procedure, ventricular arrhythmia, cardiac arrest, myocardial infarction, acute coronary syndrome, unstable angina, coronary artery disease, and congestive heart failure; cerebrovascular disease includes baseline history of any of the following: stroke, TIA, peripheral vascular disease, peripheral arterial disease

fSystemic therapy includes biologics listed above and the non-biologics apremilast, cyclosporine, acitretin, and methotrexate

All measures of clinical severity of psoriasis included in the study differed significantly among groups (BSA: P < 0.001; PASI: P = 0.003; IGA: P = 0.004) (Table 2). The biologic-naïve (mean BSA affected 15.0% [SD 13.6%]; mean PASI score 8.9 [7.4]; mean IGA score 2.9 [0.8]) and four or more prior biologics (mean BSA affected 14.6% [15.8%]; mean PASI score 9.6 [9.5]; mean IGA score 3.0 [0.8]) groups consistently showed the highest mean scores of clinical severity (Table 2).

The mean duration of psoriasis (P < 0.001) generally increased with more prior biologic therapies (mean duration 10.8 [SD 11.6] years in the biologic-naïve group and 19.2 [12.4] years in the four or more prior biologics group) (Table 2). The proportion of patients with dermatologist-diagnosed PsA was significantly different among groups (P < 0.001), with the lowest rate in the biologic-naïve group (13.5%) and the highest rate in the four or more prior biologics group (55.2%). Similarly, the proportion of patients with PEST score ≥ 3 (P < 0.001) was lowest in the biologic-naïve group (19.0%) and highest in the four or more prior biologics group (44.9%). The mean duration of PsA (P < 0.001) was shortest in the one prior biologic group (6.2 [8.4] years) and longest in the three prior biologics group (11.6 [9.1] years). In terms of concomitant therapies, use of another systemic therapy generally increased with a greater number of prior biologics (P = 0.009), whereas use of topical agents showed the opposite relationship (P = 0.02).

Patient-Reported Outcome Measures

At baseline, most PROM results differed significantly across patients with psoriasis when stratified according to prior number of biologics (Table 3). Mean overall itch/pruritus (P < 0.001) and PGA (P = 0.001) were highest in the four or more prior biologics (59.0 [SD 32.0] and 52.5 [28.9], respectively) and biologic-naïve (59.3 [31.4] and 52.4 [28.2]) groups, whereas mean overall fatigue (P < 0.001) and skin pain (P = 0.004) were highest in the four or more prior biologics group (45.6 [31.1] and 40.7 [33.4], respectively) and generally decreased with fewer prior biologic therapies.

Table 3.

Baseline patient-reported outcome measures for patients with plaque psoriasis who initiated guselkumab in CorEvitas’ Psoriasis Registry by number of prior biologics

| Characteristicsa | Number of prior biologicsb (n) | P valuec | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 (n = 127) | 1 (n = 171) | 2 (n = 150) | 3 (n = 110) | 4+ (n = 129) | ||

| Overall patient-reported outcomes, mean (SD) | ||||||

| Overall itch/pruritus (VAS 0–100) | 59.3 (31.4) | 45.5 (34.3) | 47.7 (34.2) | 48.3 (33.9) | 59.0 (32.0) | < 0.001 |

| Overall fatigue (VAS 0–100) | 34.5 (27.4) | 31.6 (27.5) | 32.8 (28.3) | 37.1 (32.5) | 45.6 (31.1) | < 0.001 |

| Overall skin pain (VAS 0–100) | 33.7 (32.6) | 28.0 (30.6) | 31.5 (31.1) | 33.2 (35.8) | 40.7 (33.4) | 0.004 |

| PGA (VAS 0–100) | 52.4 (28.2) | 41.7 (29.4) | 44.2 (29.2) | 43.2 (27.6) | 52.5 (28.9) | 0.001 |

| WPAI, mean (SD) | ||||||

| Currently employed, n (%) | 92 (72.4) | 111 (65.3) | 110 (73.8) | 74 (67.3) | 85 (65.9) | 0.39 |

| % of work hours missed due to PsO |

n = 81 5.1 (17.8) |

n = 95 3.2 (12.4) |

n = 94 4.2 (16.6) |

n = 66 1.5 (5.1) |

n = 82 6.1 (17.8) |

0.16 |

| % of impairment while working due to PsO |

n = 79 23.1 (25.4) |

n = 96 14.8 (22.8) |

n = 95 413.1 (22.2) |

n = 66 10.8 (18.6) |

n = 80 16.9 (23.0) |

< 0.001 |

| % of work hours affected by PsO |

n = 79 24.3 (26.5) |

n = 94 16.4 (24.1) |

n = 92 13.9 (23.9) |

n = 66 11.6 (19.6) |

n = 80 19.1 (24.8) |

< 0.001 |

| % of daily activities impaired by PsO |

n = 125 28.8 (29.3) |

n = 168 19.0 (25.8) |

n = 150 17.4 (24.0) |

n = 108 21.3 (27.6) |

n = 124 26.5 (29.8) |

< 0.001 |

| DLQI (score 0–30), mean (SD) | 9.4 (5.5) | 7.3 (6.0) | 6.5 (5.6) | 7.5 (6.1) | 9.2 (6.7) | < 0.001 |

| DLQI “effect on life”, n (%) | 0.001 | |||||

| 0–1: none | 7 (5.6) | 32 (18.7) | 30 (20.1) | 16 (14.7) | 10 (7.8) | |

| 2–5: small | 28 (22.4) | 52 (30.4) | 48 (32.2) | 34 (31.2) | 36 (28.1) | |

| 6–10: moderate | 41 (32.8) | 38 (22.2) | 40 (26.8) | 28 (25.7) | 36 (28.1) | |

| 11–20: very large | 46 (36.8) | 43 (25.1) | 28 (18.8) | 26 (23.9) | 36 (28.1) | |

| 21–30: extremely large | 3 (2.4) | 6 (3.5) | 3 (2.0) | 5 (4.6) | 10 (7.8) | |

| EQ-5D VAS (0–100), mean (SD) | 72.6 (21.5) | 75.8 (18.1) | 73.7 (18.3) | 70.4 (19.9) | 65.0 (24.2) | < 0.001 |

| ED-5D-3L categorical domains, n (%)d | ||||||

| Walking | 16 (13.1) | 38 (22.5) | 34 (22.8) | 35 (32.7) | 52 (40.9) | < 0.001 |

| Self-care | 4 (3.3) | 10 (5.9) | 12 (8.1) | 9 (8.5) | 22 (17.5) | < 0.001 |

| Usual activities | 39 (31.2) | 41 (24.0) | 35 (23.5) | 34 (31.8) | 51 (40.2) | 0.01 |

| Pain and discomfort | 61 (49.6) | 79 (46.5) | 77 (51.7) | 59 (55.7) | 80 (64.0) | 0.04 |

| Anxiety and depression | 33 (27.3) | 51 (30.2) | 39 (26.4) | 36 (34.0) | 48 (38.1) | 0.22 |

| Problems with sleeping | 21 (16.7) | 25 (14.7) | 29 (19.5) | 17 (15.6) | 22 (17.1) | 0.84 |

DLQI Dermatology Life Quality Index, EQ-5D EuroQoL-5 dimensions, EQ-5D-3L EuroQoL-5 dimensions, 3 levels, PsO psoriasis, SD standard deviation, VAS visual analog scale

aNot all patients provided responses to all patient-reported outcomes; item non-response was < 5% for all cells unless denominator is reported. Note that the three WPAI summary scores related to working are applicable only to those who are currently employed

bBiologic medications included adalimumab, brodalumab, certolizumab pegol, etanercept, guselkumab, infliximab, ixekizumab, secukinumab, and ustekinumab

cKruskal–Wallis tests for continuous variables and χ2 tests or Fisher’s exact tests for categorical variables. Statistically significant differences (P < 0.05) are bolded

dPercentage of patients reporting at least some problem

Among patients who were employed at the index date, the productivity of those in the biologic-naïve and four or more prior biologics groups was generally the most impacted by psoriasis, as assessed using the WPAI questionnaire (Table 3). The mean percentage of impairment while working (P < 0.001), the overall percentage of work hours affected (P < 0.001), and the percentage of daily activities impaired (P < 0.001) were all highest in the biologic-naïve group (23.1% [25.4%], 24.3% [26.5%], and 28.8% [29.3%], respectively).

Similarly, QoL was most impaired among patients in the biologic-naïve and four or more prior biologics groups, as assessed using the DLQI questionnaire (Table 3). Mean DLQI scores (P < 0.001) were 9.4 (SD 5.5) in the biologic-naïve group and 9.2 (6.7) in the four or more prior biologics group, and the distribution of DLQI “effect on life” (P = 0.001) showed that these groups had the highest proportion of patients whose scores showed a moderate or greater impact of psoriasis on QoL (72.0% and 64.1%, respectively).

Scores on the EQ-5D VAS (0–100) also differed significantly across groups (P < 0.001), with a general decline in mean score with more prior biologic therapies (Table 3). The four or more prior biologics group had the lowest mean score (65.0 [SD 24.2]), indicating the worst perceived health state across groups; the highest mean score was observed in the one prior biologic group (75.8 [18.1]). A significant difference was also observed across groups on most EQ-5D-3L categorical domains (P < 0.05 for all domains except for anxiety/depression). The four or more prior biologics group had the highest proportion of patients who reported at least some problem on each domain, and the proportion of patients reporting issues generally increased with more prior biologic therapies. Problems with sleeping did not differ across groups (P = 0.84).

Baseline Characteristics and Patient-Reported Outcome Measures Among Patients with Psoriasis and Concomitant Psoriatic Arthritis

Among the 251 patients (37.0%) with concomitant dermatologist-diagnosed PsA, 17 patients (6.8%) were biologic naïve and the other 234 patients (93.2%) had previous experience with biologics (Table 4). Baseline demographics differed between groups for several variables, including but not limited to the proportion of white patients (76.5% for the biologic-naïve group vs. 81.2% for the biologic-experienced group, standardized difference = 0.11), mean body weight (93.5 [SD 23.5] kg for the biologic-naïve group vs. 98.6 [27.2] kg for the biologic-experienced group, standardized difference = 0.20), and the proportion of patients with BMI > 30 kg/m2 (52.9% for the biologic-naïve group vs. 64.1% for the biologic-experienced group, standardized difference = 0.22).

Table 4.

Baseline demographics and disease characteristics of patients with plaque psoriasis and concomitant dermatologist-diagnosed psoriatic arthritis who initiated guselkumab in CorEvitas’ Psoriasis Registry by prior biologic use

| Characteristicsa | Prior biologic useb (n) | Standardized differencec | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biologic-naïve (n = 17) | Biologic-experienced (n = 234) | ||

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 53.8 (10.9) | 52.9 (13.0) | 0.07 |

| Female, n (%) | 10 (58.8) | 127 (54.3) | 0.09 |

| White, n (%) | 13 (76.5) | 190 (81.2) | 0.11 |

| Private health insurance, n (%) | 16 (94.1) | 185 (79.1) | 0.45 |

| Some college or more, n (%) | 12 (70.6) | 165 (70.5) | 0.00 |

| Employed full time n, (%) | 11 (64.7) | 135 (57.7) | 0.14 |

| Current smoker, n (%) | 4 (25.0) | 45 (19.2) | 0.14 |

| Body weight (kg), mean (SD) | 93.5 (23.5) | 98.6 (27.2) | 0.20 |

| BMI > 30 kg/m2, n (%) | 9 (52.9) | 150 (64.1) | 0.22 |

| History of comorbidities, n (%) | |||

| Cancerd | 0 (0.0) | 12 (5.1) | 0.33 |

| Serious infections | 0 (0.0) | 15 (6.4) | 0.37 |

| Cardiovascular diseasee | 2 (11.8) | 12 (5.1) | 0.24 |

| Hypertension | 7 (41.2) | 51 (21.8) | 0.43 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 1 (5.9) | 26 (11.1) | 0.19 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 3 (17.6) | 14 (6.0) | 0.37 |

| Crohn’s disease | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.9) | 0.13 |

| Ulcerative colitis | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.9) | 0.13 |

| Depression | 2 (11.8) | 22 (9.4) | 0.08 |

| Anxiety | 2 (11.8) | 23 (9.8) | 0.06 |

| BSA (%), mean (SD) | 15.1 (13.7) | 11.9 (14.2) | 0.23 |

| PASI (score 0–72), mean (SD) | 10.9 (7.5) | 8.0 (8.1) | 0.38 |

| IGA, mean (SD) | 3.3 (0.7) | 2.8 (0.9) | 0.58 |

| Psoriasis morphology | |||

| Scalp | 10 (58.8) | 95 (40.6) | 0.37 |

| Nail | 3 (17.6) | 56 (23.9) | 0.16 |

| Palmoplantar | 2 (11.8) | 49 (20.9) | 0.25 |

| Genital | 6 (35.3) | 15 (6.4) | 0.76 |

| Psoriasis duration (years), mean (SD) | 20.6 (15.7) | 17.8 (13.1) | 0.19 |

| PsA, n (%) | 17 (100) | 234 (100) | – |

| Confirmed by rheumatologist, n/N1 (%) | 10/16 (62.5) | 103/200 (51.5) | 0.22 |

| PsA duration (years), mean (SD) |

n = 16 10.5 (15.4) |

n = 210 9.3 (8.5) |

0.10 |

| PEST score ≥ 3, n/N1 (%) | 9/17 (52.9) | 130/230 (56.5) | 0.07 |

| Concomitant therapy, n (%) | |||

| Systemic therapyf | 1 (5.9) | 49 (20.9) | 0.45 |

| Topical agents | 11 (64.7) | 84 (35.9) | 0.60 |

BMI body mass index, BSA body surface area, IGA Investigator’s Global Assessment, PASI Psoriasis Area Severity Index, PEST Psoriasis Epidemiology Screening Tool, PsA psoriatic arthritis, SD standard deviation, TIA transient ischemic attack

aItem non-response was < 6% among biologic-naïve patients and < 1% among biologic-experienced patients for all cells, unless denominator is reported

bBiologic medications included adalimumab, brodalumab, certolizumab pegol, etanercept, guselkumab, infliximab, ixekizumab, secukinumab, and ustekinumab

cMeaningful differences (standardized difference > 0.10) are bolded

dCancer includes lymphoma, lung, breast, skin (basal cell, squamous cell, melanoma), and any other cancers

eCardiovascular disease includes baseline history of any of the following: cardiac revascularization procedure, ventricular arrhythmia, cardiac arrest, myocardial infarction, acute coronary syndrome, unstable angina, coronary artery disease, and congestive heart failure; cerebrovascular disease includes baseline history of any of the following: stroke, TIA, peripheral vascular disease, peripheral arterial disease

fSystemic therapy includes biologics listed above and the non-biologics apremilast, cyclosporine, acitretin, and methotrexate

Most disease-related characteristics differed meaningfully between groups (Table 4). The proportions of patients with specific comorbidities differed meaningfully between groups for most conditions assessed; the directional differences varied by comorbidity type. Mean scores on all tools used to assess the clinical severity of psoriasis were meaningfully worse in the biologic-naïve group than in the biologic-experienced group, including BSA (15.1% [SD 13.7%] vs. 11.9% [14.2%], standardized difference = 0.23), PASI (10.9 [7.5] vs. 8.0 [8.1], standardized difference = 0.38), and IGA (3.3 [0.7] vs. 2.8 [0.9], standardized difference = 0.58) scores.

The mean duration of psoriasis was longer for the biologic-naïve group than for the biologic-experienced group (20.6 [SD 15.7] years vs. 17.8 [13.1] years, standardized difference = 0.19), but the duration of PsA was not meaningfully different between groups (standardized difference = 0.10) (Table 4). The proportion of patients with PEST score ≥ 3 also did not differ meaningfully between groups (standardized difference = 0.07), but the proportion of patients who had their diagnosis of PsA confirmed by a rheumatologist was meaningfully higher in the biologic-naïve group than in the biologic-experienced group (62.5% vs. 51.5%, standardized difference = 0.22). In terms of concomitant therapies, use of another systemic therapy was meaningfully higher among biologic-experienced patients than among biologic-naïve patients (standardized difference = 0.45), whereas use of topical agents showed the opposite relationship (standardized difference = 0.60).

There were meaningful differences between biologic-naïve and biologic-experienced patients with PsA on most of the PROMs included in this study (Table 5). The biologic-naïve group had meaningfully higher mean scores than the biologic-experienced group for overall itch/pruritus (76.9 [SD 21.5] vs. 54.1 [33.5], standardized difference = 0.81), fatigue (50.6 [27.9] vs. 44.8 [31.1], standardized difference = 0.20), skin pain (53.7 [30.9] vs. 40.8 [33.4], standardized difference = 0.40), PGA (66.6 [18.9] vs. 50.3 [27.7], standardized difference = 0.69), joint pain due to PsA (49.9 [28.5] vs. 45.6 [32.1], standardized difference = 0.14), and wellness as a result of PsA (52.6 [28.8] vs. 43.2 [30.2], standardized difference = 0.32), indicating more severe symptoms. Among patients who were employed at the index date, productivity impairments caused by psoriasis were meaningfully greater among biologic-naïve patients than biologic-experienced patients in terms of the mean percentage of impairment while working (35.5% [SD 28.9%] vs. 16.8% [24.1%], standardized difference = 0.70), the mean percentage of work hours affected (37.8% [30.3%] vs. 18.3% [26.1%], standardized difference = 0.69), and the mean percentage of daily activities impaired by psoriasis (40.9% [26.9%] vs. 29.1% [30.0%], standardized difference = 0.41) (Table 5). The mean percentage of work hours missed because of psoriasis did not differ meaningfully between biologic-naïve and biologic-experienced patients (4.3% [11.7%] vs. 5.8% [17.8%], standardized difference = 0.10).

Table 5.

Baseline patient-reported outcome measures for patients with plaque psoriasis and concomitant dermatologist-diagnosed psoriatic arthritis who initiated guselkumab in CorEvitas’ Psoriasis Registry by prior biologic use

| Characteristicsa | Prior biologic useb (n) | Standardized differencec | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biologic-naïve (n = 17) | Biologic-experienced (n = 234) | ||

| Overall patient-reported outcomes, mean (SD) | |||

| Overall itch/pruritus (VAS 0–100) | 76.9 (21.5) | 54.1 (33.5) | 0.81 |

| Overall fatigue (VAS 0–100) | 50.6 (27.9) | 44.8 (31.1) | 0.20 |

| Overall skin pain (VAS 0–100) | 53.7 (30.9) | 40.8 (33.4) | 0.40 |

| PGA (VAS 0–100) | 66.6 (18.9) | 50.3 (27.7) | 0.69 |

| PsA patient-reported outcomes, n | 16 | 206 | |

| Joint pain due to PsA (VAS 0–100), mean (SD) | 49.9 (28.5) | 45.6 (32.1) | 0.14 |

| Wellness as a result of PsA (VAS 0–100), mean (SD) | 52.6 (28.8) | 43.2 (30.2) | 0.32 |

| WPAI, mean (SD) | |||

| Currently employed, n (%) | 12 (70.6) | 150 (64.1) | 0.14 |

| % of work hours missed due to PsO |

n = 10 4.3 (11.7) |

n = 132 5.8 (17.8) |

0.10 |

| % of impairment while working due to PsO |

n = 10 35.5 (28.9) |

n = 130 16.8 (24.1) |

0.70 |

| % of work hours affected by PsO |

n = 10 37.8 (30.3) |

n = 129 18.3 (26.1) |

0.69 |

| % of daily activities impaired by PsO |

n = 16 40.9 (26.9) |

n = 229 29.1 (30.0) |

0.41 |

| DLQI (score 0–30), mean (SD) | 11.4 (4.8) | 8.6 (6.5) | 0.49 |

| DLQI “effect on life”, n (%) | 0.73 | ||

| 0–1: none | 0 (0.0) | 29 (12.6) | |

| 2–5: small | 2 (11.8) | 61 (26.4) | |

| 6–10: moderate | 6 (35.3) | 58 (25.1) | |

| 11–20: very large | 8 (47.1) | 69 (29.9) | |

| 21–30: extremely large | 1 (5.9) | 14 (6.1) | |

| EQ-5D VAS (0–100), mean (SD) | 62.2 (17.8) | 67.3 (21.4) | 0.26 |

| ED-5D-3L categorical domains, n (%)d | |||

| Walking | 7 (43.8) | 97 (42.2) | 0.03 |

| Self-care | 1 (6.3) | 36 (15.8) | 0.31 |

| Usual activities | 11 (68.8) | 96 (41.7) | 0.56 |

| Pain and discomfort | 13 (81.3) | 169 (73.5) | 0.19 |

| Anxiety and depression | 4 (25.0) | 95 (41.3) | 0.35 |

| Problems with sleeping | 3 (17.6) | 50 (21.6) | 0.10 |

DLQI Dermatology Life Quality Index, EQ-5D EuroQoL-5 dimensions, EQ-5D-3L EuroQoL-5 dimensions, 3 levels, PsA psoriatic arthritis, PsO psoriasis, SD standard deviation, VAS visual analog scale

aNot all patients provided responses to all patient-reported outcomes; item non-response was < 6% among biologic-naïve patients and < 3% among biologic-experienced patients for all cells, unless denominator is reported. Note that the three WPAI summary scores related to working are applicable only to those who are currently employed

bBiologic medications included adalimumab, brodalumab, certolizumab pegol, etanercept, guselkumab, infliximab, ixekizumab, secukinumab, and ustekinumab

cMeaningful differences (standardized difference > 0.10) are bolded

dPercentage of patients reporting at least some problem

Quality of life also differed between groups (Table 5). The mean DLQI score was meaningfully higher for the biologic-naïve group than for the biologic-experienced group (11.4 [SD 4.8] vs. 8.6 [6.5], standardized difference = 0.49), indicating a higher degree of QoL impairment. The distribution of DLQI “effect on life” (standardized difference = 0.73) also showed that there was a higher proportion of patients with scores representing a moderate or greater impact on QoL in the biologic-naïve group than in the biologic-experienced group (88.2% vs. 61.0%).

Similar to the other PROMs, mean scores on the EQ-5D VAS (0–100) for patients with PsA showed a meaningfully worse perceived health state among biologic-naïve patients than among biologic-experienced patients (mean scores 62.2 [SD 17.8] vs. 67.3 [21.4], standardized difference = 0.26) (Table 5). Meaningful differences between groups were also observed across most EQ-5D-3L categorical domains. A higher proportion of patients in the biologic-experienced group reported at least some issues with self-care (15.8% vs. 6.3%, standardized difference = 0.31) or anxiety and depression (41.3% vs. 25.0%, standardized difference = 0.35) than in the biologic-naïve group, whereas a higher proportion of patients in the biologic-naïve group reported issues with usual activities (68.6% vs. 41.7%, standardized difference = 0.56) or pain and discomfort (81.3% vs. 73.5%, standardized difference = 0.19) than in the biologic-experienced group. No meaningful differences were observed between groups on the problems with walking domain, or on the measure that assessed problems with sleeping.

Data for a smaller subset of patients with psoriasis and rheumatologist-confirmed PsA are included in Tables S1 and S2 in the Supplementary Material. The findings in this patient subset were generally similar to the subgroup of patients with dermatologist-diagnosed PsA. Although there were some differences in PROM scores among biologic-naïve and biologic-experienced patients with rheumatologist-confirmed PsA that directionally differed from the observations in the dermatologist-diagnosed PsA subgroup, these findings should be interpreted with caution given the small number of patients in the biologic-naïve subgroup.

Discussion

In this real-world analysis of patients with plaque psoriasis who initiated guselkumab in CorEvitas’ Psoriasis Registry, significant differences in several baseline demographics, disease characteristics, and PROMs were observed across patients stratified according to the number of previously received biologic therapies. Specifically, biologic-naïve patients and those with four or more prior biologics had the most severe disease and the worst scores on PROMs at the time of guselkumab initiation. In a subgroup of patients with psoriasis and concomitant dermatologist-diagnosed PsA, biologic-naïve patients had more severe disease and worse scores on PROMs than biologic-experienced patients at baseline.

In the full cohort of patients with psoriasis included in this study, mean body weight and the proportion of patients with BMI > 30 kg/m2 were lower among biologic-naïve patients than among those with prior biologic experience, a finding consistent with those of previous analyses of patients initiating secukinumab, ustekinumab, or brodalumab [35, 37]. High BMI has been associated with a reduced response to biologic therapies [53, 54] and reduced drug survival [55], which may partially explain the relationship between greater previous biologic experience and increased BMI and mean body weight in this study. However, high BMI has also been associated with increased disease severity [53, 54], and biologic-naïve patients initiating guselkumab in the present study had among the most severe disease, along with those who had previously received four or more biologic therapies. Further, there is evidence showing that some biologic drugs may be associated with weight gain among patients with psoriasis [53, 56]; therefore, directionality remains challenging to discern. Additional work is necessary to better elucidate the relationship between BMI, body weight, and biologic experience.

Notably, biologic-naïve patients and biologic-experienced patients who had previously received four or more therapies consistently had more severe disease than those who had previously received one to three biologics, as assessed using several common clinical tools. Results from previous studies have been mixed with respect to differences in baseline clinical severity by biologic experience, but these studies have not stratified biologic-experienced patients by the number of prior biologic therapies [35–37]. Biologic-naïve patients initiating guselkumab also had the shortest mean duration of psoriasis and the lowest rate of concomitant dermatologist-diagnosed PsA, both of which generally increased as more prior biologic therapies were received. These findings are consistent with previous studies that have stratified patients initiating biologic therapies into biologic-naïve and biologic-experienced groups [35–37]. The mean duration of PsA was similar between the biologic-naïve, three prior biologic, and four or more prior biologic groups. The finding of increased disease severity among biologic-naïve patients, despite the relatively short duration of psoriasis, could be the result of poor disease control with conventional therapies among patients initiating guselkumab as a first-line biologic therapy. This may potentially indicate some degree of hesitancy to initiate a biologic until the disease becomes unmanageable; however, this is speculative, as the present study did not assess correlations between variables examined.

Significant differences between patients initiating guselkumab according to biologic experience were observed for most PROMs included in this study. Biologic-naïve patients and those who had received four or more prior biologics consistently reported the worst scores on instruments used to assess patient-reported symptom severity, work productivity impairment, and QoL. Patients who had received four or more prior biologics also had the worst average perceived health state and the highest proportion of patients reporting an impact on various aspects of life, including walking, self-care, usual activities, and pain/discomfort. It is plausible that these findings may be associated with the longer mean duration of psoriasis and/or a higher number of treatment failures among patients who have received four or more prior biologics, as results from previous studies have suggested that biologic drug survival rates decrease over time and with subsequent lines of therapy, largely because of adverse events or loss of efficacy [33, 57, 58].

In contrast to the full psoriasis cohort, the mean duration of psoriasis among patients with psoriasis and concomitant dermatologist-diagnosed PsA initiating guselkumab was longer in the biologic-naïve group than in the biologic-experienced group. Interestingly, the mean duration of psoriasis in biologic-naïve patients with concomitant PsA was nearly double that of biologic-naïve patients in the full study cohort. The duration of PsA was not meaningfully different between biologic-naïve and biologic-experienced groups as determined by the standardized difference, but it is unclear whether the difference of approximately 1.2 years is clinically meaningful. Notably, the clinical severity of psoriasis was worse among biologic-naïve patients with PsA than among biologic-experienced patients, a finding that was consistent across all instruments included in this study. In addition, results from PROMs consistently showed that biologic-naïve patients had more severe symptoms of psoriasis and PsA, greater impairments of productivity and QoL due to psoriasis, and a worse perceived health state than biologic-experienced patients at baseline. A higher proportion of biologic-naïve patients than biologic-experienced patients also had their diagnosis of PsA confirmed by a rheumatologist, potentially suggesting that the severity of disease and impact on QoL among biologic-naïve patients warranted consultation with an additional specialist. It is possible that these overall findings could have been related to the increased duration of psoriasis among the small subset of biologic-naïve patients with PsA. However, these comparisons should be interpreted with caution as there were few biologic-naïve patients with psoriasis and concomitant dermatologist-diagnosed PsA who initiated guselkumab (n = 17).

In a recent retrospective, multinational cohort study by Torres and colleagues that assessed drug survival with different biologics in patients with psoriasis, guselkumab had among the highest 18-month drug survival (91.1%; second only to risankizumab [96.4%]) of the therapies included [59]. Further, guselkumab was associated with significantly longer drug survival than ustekinumab. These findings show a high rate of drug survival among patients with psoriasis treated with guselkumab in a real-world setting. However, it should be noted that there were several key differences in baseline demographics and disease characteristics between patients initiating guselkumab in the study by Torres and colleagues and those in the present study. Therefore, additional analyses are necessary to understand drug survival and other treatment outcomes among patients with psoriasis initiating guselkumab in CorEvitas’ Psoriasis Registry.

A key strength of the present analysis is that it is among the first to describe real-world patients initiating guselkumab for the treatment of plaque psoriasis with or without concomitant PsA. Furthermore, stratifying patients by the number of previously received biologics allowed for the identification of several key differences in baseline characteristics that may have otherwise been missed if biologic-experienced patients were grouped together, as has been done in previous studies.

As this was an analysis of registry data, there are limitations inherent to observational studies that should be considered. Patients and their dermatologists voluntarily participate in CorEvitas’ Psoriasis Registry, which may limit generalizability of the findings [3, 42]. Furthermore, patients in the registry routinely visit their dermatologists, and therefore may not be representative of the overall population of patients with psoriasis in the USA [11]. In addition, the characteristics of patients with psoriasis and concomitant PsA recruited from dermatology clinics (including patients in CorEvitas’ Psoriasis Registry) may be different from those of patients recruited to registries from rheumatology clinics. Therefore, the PsA characteristics of patients included in this study may vary from those reported in previous studies. Nonetheless, patients included in this registry are likely more representative of those typically seen in clinical practice than patients enrolled in randomized trials. Another limitation is that there were relatively few biologic-naïve patients with psoriasis and concomitant dermatologist-diagnosed PsA who initiated guselkumab in the registry at the data cutoff used in this study, which may have limited the analysis of the PsA subgroup, especially since the sample size was too small to further stratify biologic-experienced patients according to number of prior biologics received. A smaller subset of patients had rheumatologist-confirmed PsA, warranting additional research in this patient population. Furthermore, rheumatologist-confirmed PsA, a subgroup of patients with dermatologist-identified PsA, was self-reported by patients and recorded by the residing dermatologist on the provider form. Therefore, patients with PsA included in this study did not necessarily have a confirmed medical record rheumatologist diagnosis.

Conclusions

Overall, this study is among the first to report real-world data for patients initiating treatment with guselkumab for plaque psoriasis with or without concomitant PsA. The results showed important differences in baseline demographics, disease characteristics, and PROMs according to previous experience with biologic therapy among patients with plaque psoriasis who initiated guselkumab. Biologic-naïve patients and those who had received four or more prior biologics had the most severe disease and the worst PROM scores at the time of guselkumab initiation. In a subgroup of patients with psoriasis and concomitant PsA, biologic-naïve patients had more severe disease and worse scores on PROMs assessing symptom severity, productivity, and QoL than biologic-experienced patients at baseline. The results of this study will help to inform the design of future analyses that will assess the real-world effectiveness of guselkumab over time and compared with other biologic therapies in this registry or other real-world data sources.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all the investigators, their clinical staff, and patients who participate in CorEvitas’ Psoriasis Registry.

Funding

This study was sponsored by CorEvitas, LLC, and the analysis was funded by Janssen Biotech, Inc. Access to study data was limited to CorEvitas and CorEvitas statisticians completed all of the analysis; all authors contributed to the interpretation of the results. CorEvitas has been supported through contracted subscriptions in the last 2 years by AbbVie, Amgen, Arena, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb, Celgene, Chugai, Eli Lilly and Company, Genentech, Gilead, GSK, Janssen, LEO, Novartis, Ortho Dermatologics, Pfizer Inc., Regeneron, Sanofi, Sun, and UCB. The Psoriasis Registry was developed in collaboration with the National Psoriasis Foundation (NPF). The journal’s rapid service fee was funded by Janssen.

Medical Writing and Editorial Assistance

The authors wish to thank Dr. Ari Mendell, Dana Anger, and Dr. Leena Patel of EVERSANA™ for their support in the development of this manuscript. This support was funded by Janssen.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Author Contributions

T. Fitzgerald, A. Teeple, K. Rowland, and R.R. McLean were responsible for study conception and design. T Fitzgerald, A. Teeple, K. Rowland, R.R. McLean were responsible for acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data. T. Fitzgerald, A. Teeple, K. Rowland, R.R. McLean, and J. Uy were responsible for drafting the manuscript, and all authors were responsible for critically revising/reviewing the manuscript and for providing final approval.

Prior Presentation

Some components of the data reported in this manuscript were previously presented at the following congresses: Walsh et al. P74. Presented at the 2019 Congress of Clinical Rheumatology; September 26–29, 2019. Callis-Duffin et al. P1597 and P1590. Presented at the 2019 Congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology; October 9–13, 2019.

Disclosures

J.A. Walsh has received grant funding or consultant fees from Janssen, Abbvie, Pfizer, Merck, Lilly, Amgen, and Novartis. K. Callis Duffin reports the following conflicts (last 12 months): consultant/advisor/advisory board member for Amgen/Celgene, Abbvie, Bristol Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, Janssen, Novartis, Pfizer, UCB, and Boehringer-Ingelheim; investigator for Abbvie, Amgen, Bristol Myers Squibb, Celgene, Lilly, Janssen, Novartis, Pfizer, Stiefel Laboratories, UCB, Ortho Dermatologics, Anaptys Bio, and Boehringer-Ingelheim. A.S. Van Voorhees reports the following conflicts: investigator for Abbvie, Celgene, and Lilly; consultant for Amgen, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb, and UCB. T. Fitzgerald, A. Teeple, K. Rowland, J. Uy, and S.D. Chakravarty are employees of Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC, and stockholders of Johnson & Johnson, of which Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC is a wholly owned subsidiary. R.R. McLean, W. Malley, and A. Cronin are employees of CorEvitas LLC. J.F. Merola is a consultant and/or investigator for Amgen, Bristol Myers Squibb, Abbvie, Dermavant, Eli Lilly, Novartis, Janssen, UCB, Sanofi, Regeneron, Sun Pharma, Biogen, Pfizer, and Leo Pharma. EVERSANA is a paid consultant of Janssen and supported in the writing and submission of this manuscript.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

All participating investigators were required to obtain full board approval for conducting research involving human subjects. Sponsor approval and continuing review was obtained through a central IRB (IntegReview, Protocol number is Corrona-PSO-500). For academic investigative sites that did not receive a waiver to use the central IRB, approval was obtained from the respective governing IRBs and documentation of approval was submitted to the sponsor prior to initiating any study procedures. All registry subjects were required to provide written informed consent prior to participating. This study was performed in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1964 and its later amendments.

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available through CorEvitas, LLC (formerly Corrona), but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under a subscription agreement for the current study, and so are not publicly available.

References

- 1.Armstrong AW, Reich K, Foley P, et al. Improvement in Patient-Reported Outcomes (Dermatology Life Quality Index and the Psoriasis Symptoms and Signs Diary) with Guselkumab in Moderate-to-Severe Plaque Psoriasis: Results from the Phase III VOYAGE 1 and VOYAGE 2 Studies. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2018;20(1):155–164. doi: 10.1007/s40257-018-0396-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blauvelt A, Papp KA, Griffiths CE, et al. Efficacy and safety of guselkumab, an anti-interleukin-23 monoclonal antibody, compared with adalimumab for the continuous treatment of patients with moderate to severe psoriasis: results from the phase III, double-blinded, placebo- and active comparator-controlled VOYAGE 1 trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76(3):405–417. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2016.11.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Strober BE, Germino R, Guana A, et al. US real-world effectiveness of secukinumab for the treatment of psoriasis: 6-month analysis from the Corrona Psoriasis Registry. J Dermatolog Treat. 2020;31(4):333–341. doi: 10.1080/09546634.2019.1603361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rachakonda TD, Schupp CW, Armstrong AW. Psoriasis prevalence among adults in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70(3):512–516. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2013.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dalgard FJ, Gieler U, Tomas-Aragones L, et al. The psychological burden of skin diseases: a cross-sectional multicenter study among dermatological out-patients in 13 European countries. J Invest Dermatol. 2015;135(4):984–991. doi: 10.1038/jid.2014.530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kwan Z, Bong YB, Tan LL, et al. Determinants of quality of life and psychological status in adults with psoriasis. Arch Dermatol Res. 2018;310(5):443–451. doi: 10.1007/s00403-018-1832-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gordon KB, Armstrong AW, Han C, et al. Anxiety and depression in patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis and comparison of change from baseline after treatment with guselkumab vs. adalimumab: results from the phase 3 VOYAGE 2 study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32(11):1940–1949. doi: 10.1111/jdv.15012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Armstrong AW, Schupp C, Wu J, Bebo B. Quality of life and work productivity impairment among psoriasis patients: findings from the National Psoriasis Foundation survey data 2003–2011. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(12):e52935. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0052935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mease PJ, Gladman DD, Papp KA, et al. Prevalence of rheumatologist-diagnosed psoriatic arthritis in patients with psoriasis in European/North American dermatology clinics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69(5):729–735. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2013.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Menter A, Strober BE, Kaplan DH, et al. Joint AAD-NPF guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with biologics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80(4):1029–1072. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.11.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mease PJ, Karki C, Liu M, et al. Discontinuation and switching patterns of tumour necrosis factor inhibitors (TNFis) in TNFi-naive and TNFi-experienced patients with psoriatic arthritis: an observational study from the US-based Corrona registry. RMD Open. 2019;5(1):e000880. doi: 10.1136/rmdopen-2018-000880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Feldman SR, Tian H, Gilloteau I, Mollon P, Shu M. Economic burden of comorbidities in psoriasis patients in the United States: results from a retrospective U.S. database. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17(1):337. doi: 10.1186/s12913-017-2278-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Feldman SR, Zhao Y, Shi L, Tran MH. Economic and comorbidity burden among patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2015;21(10):874–888. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2015.21.10.874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shah K, Mellars L, Changolkar A, Feldman SR. Real-world burden of comorbidities in US patients with psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77(2):287–92.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2017.03.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Takeshita J, Grewal S, Langan SM, et al. Psoriasis and comorbid diseases: epidemiology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76(3):377–390. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2016.07.064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Elmets CA, Leonardi CL, Davis DMR, et al. Joint AAD-NPF guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with awareness and attention to comorbidities. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80(4):1073–1113. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.11.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Noe MH, Shin DB, Doshi JA, Margolis DJ, Gelfand JM. Prescribing patterns associated with biologic therapies for psoriasis from a United States Medical Records Database. J Drugs Dermatol. 2019;18(8):745–750. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Campa M, Mansouri B, Warren R, Menter A. A review of biologic therapies targeting IL-23 and IL-17 for use in moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb) 2016;6(1):1–12. doi: 10.1007/s13555-015-0092-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smith CH, Jabbar-Lopez ZK, Yiu ZZ, et al. British Association of Dermatologists guidelines for biologic therapy for psoriasis 2017. Br J Dermatol. 2017;177(3):628–636. doi: 10.1111/bjd.15665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hawkes JE, Yan BY, Chan TC, Krueger JG. Discovery of the IL-23/IL-17 signaling pathway and the treatment of psoriasis. J Immunol. 2018;201(6):1605–1613. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1800013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ratner M. IL-17-targeting biologics aim to become standard of care in psoriasis. Nat Biotechnol. 2015;33(1):3–4. doi: 10.1038/nbt0115-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grine L, Dejager L, Libert C, Vandenbroucke RE. An inflammatory triangle in psoriasis: TNF, type I IFNs and IL-17. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2015;26(1):25–33. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2014.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Erichsen CY, Jensen P, Kofoed K. Biologic therapies targeting the interleukin (IL)-23/IL-17 immune axis for the treatment of moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34(1):30–38. doi: 10.1111/jdv.15879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.US Food and Drug Administration. TREMFYA (guselkumab) Injection. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2020/761061s007lbl.pdf. Accessed 7 Aug 2020.

- 25.Reich K, Armstrong AW, Foley P, et al. Efficacy and safety of guselkumab, an anti-interleukin-23 monoclonal antibody, compared with adalimumab for the treatment of patients with moderate to severe psoriasis with randomized withdrawal and retreatment: results from the phase III, double-blind, placebo- and active comparator-controlled VOYAGE 2 trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76(3):418–431. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2016.11.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Clinicaltrials.gov. A study of guselkumab in the treatment of participants with moderate to severe plaque-type psoriasis (VOYAGE 1). https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02207231. Accessed 2021 Jan 27.

- 27.Clinicaltrials.gov. A study of guselkumab in the treatment of participants with moderate to severe plaque-type psoriasis with randomized withdrawal and retreatment (VOYAGE 2). https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02207244. Accessed 2021 Jan 27.

- 28.Deodhar A, Helliwell PS, Boehncke WH, et al. Guselkumab in patients with active psoriatic arthritis who were biologic-naive or had previously received TNFα inhibitor treatment (DISCOVER-1): a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2020;395(10230):1115–1125. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30265-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mease PJ, Rahman P, Gottlieb AB, et al. Guselkumab in biologic-naive patients with active psoriatic arthritis (DISCOVER-2): a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2020;395(10230):1126–1136. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30263-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Armstrong AW, Foster SA, Comer BS, et al. Real-world health outcomes in adults with moderate-to-severe psoriasis in the United States: a population study using electronic health records to examine patient-perceived treatment effectiveness, medication use, and healthcare resource utilization. BMC Dermatol. 2018;18(1):4. doi: 10.1186/s12895-018-0072-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Doshi JA, Takeshita J, Pinto L, et al. Biologic therapy adherence, discontinuation, switching, and restarting among patients with psoriasis in the US Medicare population. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74(6):1057–65.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2016.01.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Norlin JM, Steen Carlsson K, Persson U, Schmitt-Egenolf M. Switch to biological agent in psoriasis significantly improved clinical and patient-reported outcomes in real-world practice. Dermatology. 2012;225(4):326–332. doi: 10.1159/000345715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gniadecki R, Kragballe K, Dam TN, Skov L. Comparison of drug survival rates for adalimumab, etanercept and infliximab in patients with psoriasis vulgaris. Br J Dermatol. 2011;164(5):1091–1096. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2011.10213.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Leman J, Burden AD. Sequential use of biologics in the treatment of moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 2012;167(Suppl 3):12–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2012.11209.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Papp KA, Gordon KB, Langley RG, et al. Impact of previous biologic use on the efficacy and safety of brodalumab and ustekinumab in patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis: integrated analysis of the randomized controlled trials AMAGINE-2 and AMAGINE-3. Br J Dermatol. 2018;179(2):320–328. doi: 10.1111/bjd.16464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gottlieb AB, Lacour JP, Korman N, et al. Treatment outcomes with ixekizumab in patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis who have or have not received prior biological therapies: an integrated analysis of two phase III randomized studies. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31(4):679–685. doi: 10.1111/jdv.13990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ger TY, Huang YH, Hui RC, Tsai TF, Chiu HY. Effectiveness and safety of secukinumab for psoriasis in real-world practice: analysis of subgroups stratified by prior biologic failure or reimbursement. Ther Adv Chronic Dis. 2019;10:2040622319843756. doi: 10.1177/2040622319843756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Costa L, Perricone C, Chimenti MS, et al. Switching between biological treatments in psoriatic arthritis: a review of the evidence. Drugs R D. 2017;17(4):509–522. doi: 10.1007/s40268-017-0215-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Harrold LR, Stolshek BS, Rebello S, et al. Impact of prior biologic use on persistence of treatment in patients with psoriatic arthritis enrolled in the US Corrona registry. Clin Rheumatol. 2017;36(4):895–901. doi: 10.1007/s10067-017-3593-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Merola JF, Lockshin B, Mody EA. Switching biologics in the treatment of psoriatic arthritis. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2017;47(1):29–37. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2017.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McInnes IB, Chakravarty SD, Apaolaza I, et al. Efficacy of ustekinumab in biologic-naïve patients with psoriatic arthritis by prior treatment exposure and disease duration: data from PSUMMIT 1 and PSUMMIT 2. RMD Open. 2019;5(2):e000990. doi: 10.1136/rmdopen-2019-000990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Strober B, Karki C, Mason M, et al. Characterization of disease burden, comorbidities, and treatment use in a large, US-based cohort: results from the Corrona Psoriasis Registry. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78(2):323–332. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2017.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.National Psoriasis Foundation. Corrona Psoriasis Registry. https://www.psoriasis.org/providers/corrona-psoriasis-registry. Accessed 2020 Jul 15.

- 44.Clinicaltrials.gov. The Corrona Psoriasis (PSO) Registry. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02707341. Accessed 2020 Jul 15.

- 45.Reilly Associates. Reilly Associates Work Productivity and Activity Questionnnaire (WPAI). http://www.reillyassociates.net/WPAI-PSORIASIS-English-US_.doc. Accessed 16 July 2020.

- 46.Finlay AY, Khan GK. Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI)–a simple practical measure for routine clinical use. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1994;19(3):210–216. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.1994.tb01167.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.EuroQoL Research Foundation. EQ-5D-3L User Guide Version 6.0, December 2018. https://euroqol.org/publications/user-guides/. Accessed 16 July 2020.

- 48.Austin PC. Balance diagnostics for comparing the distribution of baseline covariates between treatment groups in propensity-score matched samples. Stat Med. 2009;28(25):3083–3107. doi: 10.1002/sim.3697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mease PJ, Palmer JB, Hur P, et al. Utilization of the validated Psoriasis Epidemiology Screening Tool to identify signs and symptoms of psoriatic arthritis among those with psoriasis: a cross-sectional analysis from the US-based Corrona Psoriasis Registry. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2019;33(5):886–892. doi: 10.1111/jdv.15443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Strober B, Karki C, Mason M, Greenberg JD, Lebwohl M. Impact of Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) on patient reported outcomes in patients with psoriasis: results from the Corrona Psoriasis Registry. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76(6 (Suppl 1)):406. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Langley RG, Feldman SR, Nyirady J, van de Kerkhof P, Papavassilis C. The 5-point Investigator's Global Assessment (IGA) Scale: a modified tool for evaluating plaque psoriasis severity in clinical trials. J Dermatolog Treat. 2015;26(1):23–31. doi: 10.3109/09546634.2013.865009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Strober B, Greenberg JD, Karki C, et al. Impact of psoriasis severity on patient-reported clinical symptoms, health-related quality of life and work productivity among US patients: real-world data from the Corrona Psoriasis Registry. BMJ Open. 2019;9(4):e027535. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-027535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kisielnicka A, Szczerkowska-Dobosz A, Nowicki RJ. The influence of body weight of patients with chronic plaque psoriasis on biological treatment response. Postepy Dermatol Alergol. 2020;37(2):168–173. doi: 10.5114/ada.2020.94835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cassano N, Galluccio A, De Simone C, et al. Influence of body mass index, comorbidities and prior systemic therapies on the response of psoriasis to adalimumab: an exploratory analysis from the APHRODITE data. J Biol Regul Homeost Agents. 2008;22(4):233–237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zweegers J, van den Reek JM, van de Kerkhof PC, et al. Body mass index predicts discontinuation due to ineffectiveness and female sex predicts discontinuation due to side-effects in patients with psoriasis treated with adalimumab, etanercept or ustekinumab in daily practice: a prospective, comparative, long-term drug-survival study from the BioCAPTURE registry. Br J Dermatol. 2016;175(2):340–347. doi: 10.1111/bjd.14552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Saraceno R, Schipani C, Mazzotta A, et al. Effect of anti-tumor necrosis factor-alpha therapies on body mass index in patients with psoriasis. Pharmacol Res. 2008;57(4):290–295. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2008.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Iskandar IYK, Warren RB, Lunt M, et al. Differential drug survival of second-line biologic therapies in patients with psoriasis: observational cohort study from the British Association of Dermatologists Biologic Interventions Register (BADBIR) J Invest Dermatol. 2018;138(4):775–784. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2017.09.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.No DJ, Inkeles MS, Amin M, Wu JJ. Drug survival of biologic treatments in psoriasis: a systematic review. J Dermatolog Treat. 2018;29(5):460–466. doi: 10.1080/09546634.2017.1398393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Torres T, Puig L, Vender R, et al. Drug survival of IL-12/23, IL-17 and IL-23 inhibitors for psoriasis treatment: a retrospective multi-country, multicentric cohort study. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2021;22(4):567–579. doi: 10.1007/s40257-021-00598-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available through CorEvitas, LLC (formerly Corrona), but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under a subscription agreement for the current study, and so are not publicly available.