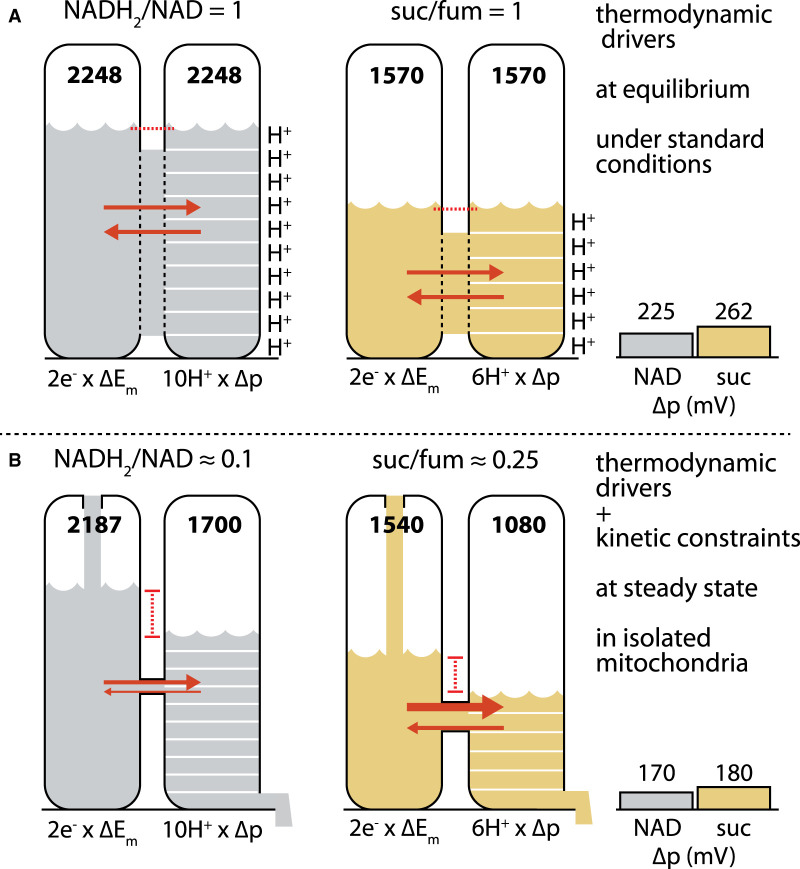

Figure 1. Thermodynamic and kinetic determinants of protonmotive force (pmf, Δp) in (A) isolated mitochondria under standard conditions at equilibrium and (B) liver mitochondria oxidizing excess substrates (succinate or pyruvate/malate) in steady-state resting conditions.

(A) Under standard equilibrium conditions (50% reduction in redox couples, pH 7.4) at equilibrium, 2ΔEm for NADH2 oxidation is 2248 mV, supporting an nΔp of 2248 mV (n is the gearing: the number of protons pumped as 2e− flow to O2). 2ΔEm for succinate oxidation is 1570 mV, supporting an nΔp of 1570 mV. Since n is 10 for NADH2 oxidation and 6 for succinate oxidation, Δp values of 225 mV (from NADH2 oxidation) and 262 mV (from succinate oxidation) result. (B) Kinetics of supply and demand in liver mitochondria under non-standard conditions and steady-state resting respiration yield lower 2ΔEh than under standard conditions because redox couples are more oxidized: for NADH2, 2ΔEh is 2187 mV; for succinate, 2ΔEh is 1540 mV. Net flow between 2ΔEh and nΔp requires that nΔp < 2ΔEh. The diameter of the connecting pipe reflects the restriction of flow between the two pools that contributes to displacement between 2ΔEh and nΔp. Succinate oxidation generally operates faster, and closer to equilibrium than NADH2 oxidation, shown by a wider pipe diameter and smaller difference in pool levels. These constraints operating on thermodynamic drivers result in Δp of ∼170 mV (NADH2) and 180 mV (succinate). Extensive kinetic controls on succinate dehydrogenase/Complex II activity (which alter the diameter of the connecting pipe in this analogy) may serve to keep the pmf supported by succinate oxidation within acceptable limits in cells (see text). Suc/fum: succinate/fumarate. ‘NAD' and ‘suc' in plots at right refer to the NADH2/NAD couple and succinate/fumarate couple, respectively.