Abstract

Gastrointestinal mucositis is one of the most debilitating side effects of the chemotherapeutic agent irinotecan (CPT-11). Andrographolide, a natural bicyclic diterpenoid lactone, has been reported to possess anti-colitis activity. In this study, andrographolide treatment was found to significantly relieve CPT-11-induced colitis in tumor-bearing mice without decreasing the tumor suppression effect of CPT-11. CPT-11 causes DNA damage and the release of double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) from the intestine, leading to cyclic-GMP-AMP synthase (cGAS)‒stimulator of interferon genes (STING)-mediated colitis, which was significantly decreased by andrographolide both in vivo and in vitro. Mechanistic studies revealed that andrographolide could promote homologous recombination (HR) repair and downregulate dsDNA‒cGAS‒STING signaling and contribute to the improvement of CPT-11-induced gastrointestinal mucositis. These results suggest that andrographolide may be a novel agent to relieve gastrointestinal mucositis caused by CPT-11.

KEY WORDS: CPT-11, Gastrointestinal mucositis, Andrographolide, Homologous recombination, cGAS‒STING

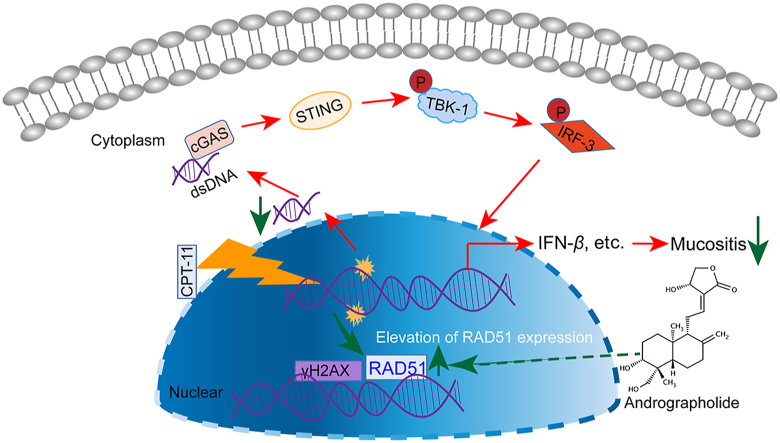

Graphical abstract

Andrographolide could accelerate HR repair of DNA damage-induced by elevating expression of RAD51 and downregulate cGAS‒STING, thereby improving mucosal damage.

1. Introduction

Irinotecan (CPT-11) is a basic chemotherapy drug for the first or second-line treatment for patients with advanced colorectal cancer1. According to the statistical data, up to 87% of patients who received CPT-11 treatment would suffer from clinically significant diarrhea, with 30%–40% incidence of diarrhea at grade 3 or 4. Long-duration diarrhea may impede the quality of life. In addition, the effectiveness of chemotherapy would be influenced by the need to lower the dosage or even suspend the treatment. In a murine model, CPT-11 dose-dependently induced mucosal colon length reduction2,3.

CPT-11, derived from the plant alkaloid camptothecin, is a topoisomerase I inhibitor. During DNA replication, topoisomerase I relieves torsional strain by inducing reversible single-strand breaks. CPT-11 prevents the religation of these single-strand breaks by interacting with the topoisomerase I/DNA complex, leading to lethal double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) breaks. This action eventually causes the retardation of DNA replication and triggers apoptotic cell death4. Besides, cell death, damaged DNA accumulation, especially dsDNA in the cytosol, triggers the innate immune response and pro-inflammatory cytokine production5. dsDNA can be sensed by its receptor, cyclic-GMP-AMP synthase (cGAS), through direct colocalization with markers of DNA damage, such as phosphorylated histone H2AX (γH2AX), or translocating into the nucleus and binding to locations of double strand breaks (DSBs)6. dsDNA triggers conformational changes and induces the enzymatic activity of cGAS, which activates the adapter molecule named stimulator of interferon genes (STING). Upon activation, STING activated the subsequent signal axis including TANK-binding kinase 1 (TBK1) and interferon regulatory factor 3 (IRF3). Phosphorylated IRF3 activates the transcription of genes, such as interferon-β (IFN-β), chemokine ligand 10 (CXCL10), and C–C motif chemokine 5 (CCL5), after dimerization and translocation to the nucleus. Overactivation of STING-mediated signaling has been demonstrated to be involved in the several pathological processes, including Aicardi‒Goutières syndrome, in a range of more complex inflammatory diseases7, 8, 9.

The natural product andrographolide isolated from the plant Andrographis paniculata exhibits wide range of bioactivities such as anti-inflammatory, anti-tumor, antibiotic, anti-obesity, immunomodulatory, anti-virus, and hypoglycemic activities10, 11, 12, 13. Previous studies have shown that andrographolide significantly alleviates colitis induced by 2,4,6-trinitrobenzenesulfonic acid (TNBS) or dextran sulfate sodium (DSS)14,15. In this study, the effect of andrographolide on CPT-11-induced colitis in vivo and characterized the probable mechanism of action in intestinal epithelial cells, such as the HCT116 cell line in vitro, were investigated. Our data revealed that accelerating DNA damage homologous recombination (HR) repair and downregulation of cGAS–STING by andrographolide is one of the principal mechanisms for protecting the colon from damage induced by CPT-11. Furthermore, andrographolide at the indicated doses for colitis reversion did not alter the tumor suppression effect of CPT-11. These findings provide a scientific basis for the utility of this clinically used medicine for amelioration relieving CPT-11-induced side-effects in cancer patients.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Materials

CPT-11 was provided by HengRui Medicine Co., Ltd. (Lianyungang, China). Andrographolide was purchased from Sigma–Aldrich (St. Louis, USA). Primary antibodies against cGAS (15102S), STING (13647S), p-TBK1 (5483T), p-IRF3 (37829S), γH2AX (80312), DNA repair protein RAD51 homolog 1 (RAD51, 88755), β-actin (3700), and β-tubulin (2128) were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA, USA). Anti-dsDNA (sc-80772) were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (CA, USA). Anti-CD8-FITC (100706), anti-CD4-FITC (100406), and anti-CD11b-PE (101207) were obtained from BioLegend (San Diego, CA, USA). Anti-CD11b (A15390) antibody and Quant-iT™ PicoGreen™ dsDNA Assay Kit were purchased from Life Technology (Waltham, MA, USA). The Trevigen Comet Assay™ Kit was obtained from Trevigen Inc. (Gaithersburg, MD, USA). Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick-end labeling (TUNEL) assay kits and Cell Counting Kit 8 (CCK-8) were purchased from Vazyme Biotech Co., Ltd. (Nanjing, China). Immunohistochemical (IHC) analysis Kit (3,3ʹ-diaminobenzidine, DAB) was purchased from Proteintech (Wuhan, China). pHPRT-DR-GFP, pCBASceI, and pimEJ5GFP (Addgene plasmid #44026, #26476, and #26477) were purchased from Addgene (USA).

2.2. Cell culture

HCT116 and HT29 (human colon cancer) and CT26 (mouse colon cancer) cell lines were obtained from the Type Culture Collection of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (Shanghai, China). CT26 and HT29 cells were cultured in DMEM culture medium (Biological Industries, Israel), and HCT116 cells were cultured in McCoy's 5A culture medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Biological Industries), in an incubator with a humidified 5% CO2 at 37 °C.

2.3. Animals and syngeneic model

BALB/c mice and syngeneic models were raised and conducted as previously described13. Animal welfare and experimental procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Nanjing University (Nanjing, China). All efforts were made to reduce the number of animals used and to minimize animal suffering. For the tumor-bearing syngeneic model, CT26 cells (2 × 106) were inoculated in the right flank of mice. Mice with a tumor volume of 50 mm3 were divided into four groups (n = 6 per group). Mice in group I were administered a daily oral gavage with phosphate buffer saline (PBS, vehicle); in groups II, III, and IV, mice were administered the following doses intraperitoneally: 45 mg/kg CPT-11 on Days 1–5 and 22.5 mg/kg on Days 6–8. Mice in groups III and IV were also administered andrographolide (12.5 and 25 mg/kg) by intraperitoneal injection on Days 1–10. Tumor largest diameter (a) and perpendicular (b) of the tumor were measured and tumor volume were calculated (volume = a × b2/2). After sacrificing the mice on Day 11, solid tumors were separated. For the non-tumor-bearing model, C57BL/6 mice were divided into four groups. Mice in groups II, III, and IV were intraperitoneally injected with 45 mg/kg CPT-11 on Days 1–4, and mice in groups III and IV were intraperitoneally injected with andrographolide at 12.5 and 25 mg/kg, respectively, on Days 5–9. Body weight was measured daily, and the mice were sacrificed on Day 10.

2.4. Cell viability

Three thousand cells were plated into 96-well plates and incubated with various concentrations of CPT-11 and/or andrographolide as indicated. At the indicated timepoints, cell viability was examined by the CCK-8 assay. CCK-8 (10 μL/well) was added and after 4 h of additional incubation, absorption values at 470 nm were detected.

2.5. Western blot and real-time PCR

Western blot and real-time PCR were conducted as described previously reported13. Primer sequences were as follows: human IFN-β: 5ʹ-GCTTGGATTCCTACAAAGAAGCA-3ʹ and 5ʹ-ATAGATGGTCAATGCGGCGTC-3ʹ; human CXCL10: 5ʹ-GTGGCATTCAAGGAGTACCTC-3ʹ and 5ʹ-TGATGGCCTTCGATTCTGGATT-3ʹ; human CCL5: 5ʹ-CCAGCAGTCGTCTTTGTCAC-3ʹ and 5ʹ-CTCTGGGTTGGCACACACTT-3ʹ; human TGF-β: 5ʹ-CCTCTCTCTAATCAGCCCTCTG-3ʹ and 5ʹ-GAGGACCTGGGAGTAGATGAG-3ʹ; human IL-1β: 5ʹ-GGACAAGCTGAGGAAGATGC-3ʹ and 5ʹ-TCCATATCCTGTCCCTGGAG-3ʹ; human IL-18: 5ʹ-CTTCCAGATCGCTTCCTCTC-3ʹ and 5ʹ-TCAAATAGAGGCCGATTTCC-3ʹ; human IL-6: 5ʹ-CAGCCCTGAGAAAGGAGACAT-3ʹ and 5ʹ-GGTTCAGGTTGTTTTCTGCCA-3ʹ; human actin: 5ʹ-CATGTACGTTGCTATCCAGGC-3ʹ and 5ʹ-CTCCTTAATGTCACGCACGAT-3ʹ; mouse Ifn-β: 5ʹ-AGCTCCAAGAAAGGACGAACA-3ʹ and 5ʹ-GCCCTGTAGGTGAGGTTGAT-3ʹ; mouse Cxcl10: 5ʹ-CCAAGTGCTGCCGTCATTTTC-3ʹ and 5ʹ-TCCCTATGGCCCTCATTCTCA-3ʹ; mouse Ccl5: 5ʹ-TTTGCCTACCTCTCCCTCG-3ʹ and 5ʹ-AAGTCTGGCTCGTTCTCAGTG-3ʹ; mouse Tgf-β: 5ʹ-TGAACTTCGGGGTGATCGGTC-3ʹ and 5ʹ-AGCCTTGTCCCTTGAAGAGAAC-3ʹ; mouse Il-1β: 5ʹ-CTTCAGGCAGGCAGTATCACTC-3ʹ and 5ʹ-TGCAGTTGTCTAATGGGAACGT-3ʹ; mouse Il-18: 5ʹ-GCCTCAAACCTTCCAAATCA-3ʹ and 5ʹ-TGGATCCATTTCCTCAA AGG-3ʹ; mouse Il-6: 5ʹ-ACAACCACGGCCTTCCCTAC-3ʹ and 5ʹ-TCTCATTTCCACGATTTCCCAG-3ʹ; mouse actin: 5ʹ-GTATGCCTCGGTCGTACCA-3ʹ and 5ʹ-CTTCTGCATCCTGTCAGCAA-3ʹ.

2.6. IHC and immunofluorescence (IF)

Staining was performed as previously reported16. The sections were blocked with 3% goat serum, and incubated with primary antibodies for 4 h at room temperature. The sections were then detected using DAB (IHC) or fluorescent labeled antibodies (IF). Images were acquired, and the optical or fluorescence intensity was evaluated by ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, USA).

2.7. Quantification of dsDNA

Levels of dsDNA were detected by using the PicoGreen assay Kit (Life Technologies, USA)3. Briefly, dsDNA in cell culture medium was collected and mixed 1:1 with the PicoGreen and fluorescence was then measured (ex: 485 nm, em: 528 nm). The DNA concentrations were calculated using a standard curve.

2.8. Comet assays

Comet assays were performed as previously reported17. Cells were collected and resuspended in PBS mixed with agarose (low-melting), and 80 μL of cell suspension was spread on a comet slide. Slides were placed in lysis buffer overnight, followed by electrophoresis, transfer and stained with ethylene dibromide (EB, 20 μg/mL). Nuclei were visualized, and the percentage of DNA in the tail was determined using the Comet Score software (TriTek, USA).

2.9. DNA damage repair assays

DNA damage repair including HR and non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) repair in HCT116 cells were detected as reported18,19. Briefly, 5 × 105 HCT116 cells were co-transfected with 2 μg pCBASce or empty pcDNA vector, and either 4 μg pimEJ5-GFP or pHPRT-DR-GFP plasmid. GFP expression in cells was analyzed using FACS at 48 h.

2.10. Intestinal barrier function assay

Fluorescein isothiocyanate-labeled dextran (FITC-dextran) was used to assess intestinal barrier function as previously reported20. Mice were administrated FITC-dextran (4 kD, Sigma–Aldrich, ig, 0.6 mg/g body weight). Serum was collected 4 h later. Fluorescence emission was measured on a microplate reader (ex: 490 nm, em: 530 nm).

2.11. Statistical analysis

GraphPad Prism Software Version 5.0 (La Jolla, CA, USA) was used to analyze the data which were expressed as mean ± standard error of mean (SEM). A two-tailed Student's t-test was performed to compare the two groups, differences were considered statistically significant at P < 0.05.

3. Results

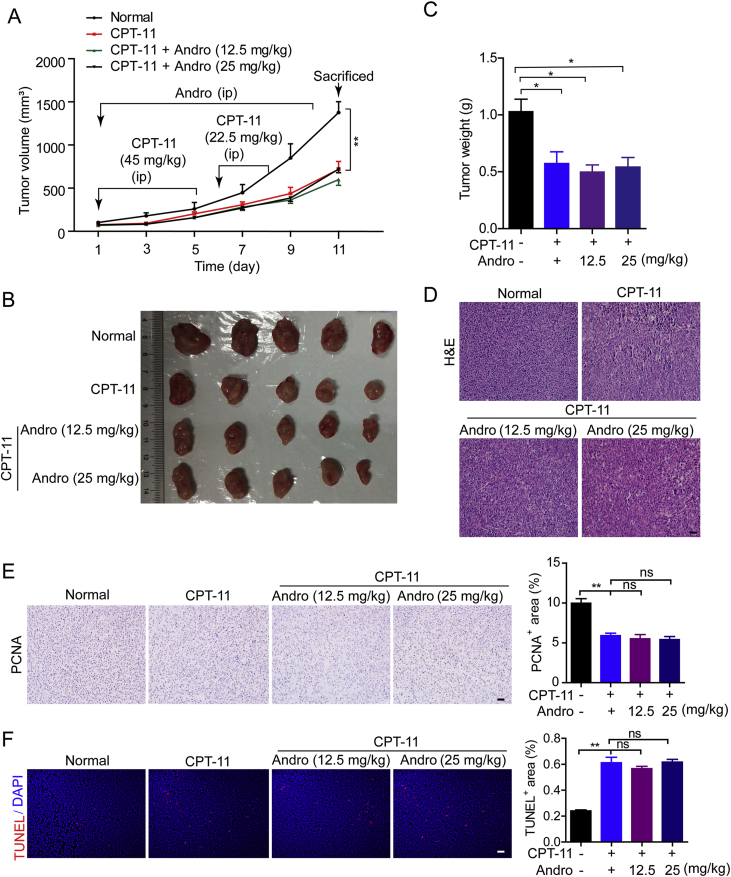

3.1. Andrographolide had no impact on the tumor suppression effect of CPT-11 in a colorectal cancer model

To examine whether andrographolide affects the chemotherapeutic effect of CPT-11, a CT26 colon cancer cell transplant mouse model was generated. CPT-11 and andrographolide treatments were conducted as described in Fig. 1A. Tumor growth was significantly inhibited by CPT-11 monotherapy, and neither dose of andrographolide promoted the tumor suppression effect of CPT-11 (andrographolide alone showed no inhibitory effect); no difference in tumor volume was observed between CPT-11 monotherapy and co-therapy with CPT-11 and andrographolide (Fig. 1A and B). Tumor weight markedly decreased with CPT-11 monotherapy compared with that in the control group, whereas the co-therapy group showed no further decrease (Fig. 1C). The morphology of tumor tissue in each group was examined by H&E staining, while proliferation and apoptosis of tumor cells were analyzed for proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) and TUNEL staining of tumor tissues (Fig. 1D‒F). In the CPT-11-treated groups, the structure of tumor tissue became loose with proliferation inhibition and enhanced apoptosis; no further increase in proliferation inhibition or enhanced apoptosis was observed in the co-therapy group. These results indicated that co-therapy with CPT-11 and andrographolide provide no improvement in the anti-neoplastic effect.

Figure 1.

Andrographolide did not alter the tumor suppressive effect of CPT-11 in vivo. Tumor-bearing mice were treated with 45 mg/kg CPT-11 (ip) on Days 1–5 and 22.5 mg/kg on Days 6–8. Meanwhile andrographolide was injected (ip, 12.5 and 25 mg/kg) on Days 1–10. (A) Schematic overview of the experiment design. ip, intraperitoneal injection. Tumor volumes were recorded. (B) Tumor was photographed. (C) Tumor tissues were weighed immediately after the masses were stripped from mice. (D) Representative images of hematoxylin-eosin (H&E) staining. (E) Expression of PCNA examined by IHC and quantified by ImageJ of three random images in each group. (F) TUNEL staining and the quantification of TUNEL-positive cells in CT26 tumor tissues. Data are represented as mean ± SEM (n = 6 in each group). ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01. ns, not significant. Scale bar: 100 μm.

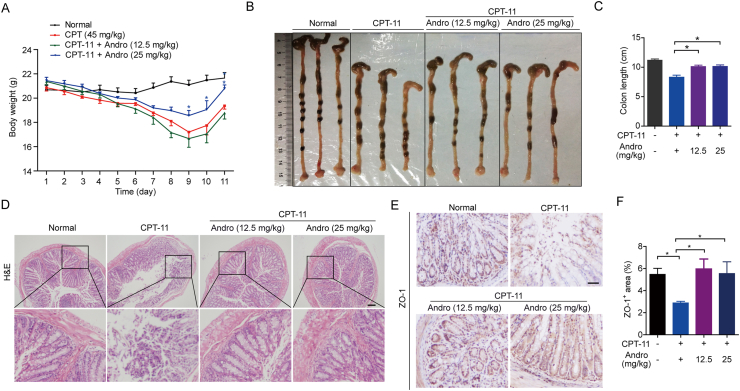

3.2. Andrographolide relieved CPT-11-induced colitis in tumor-bearing mice

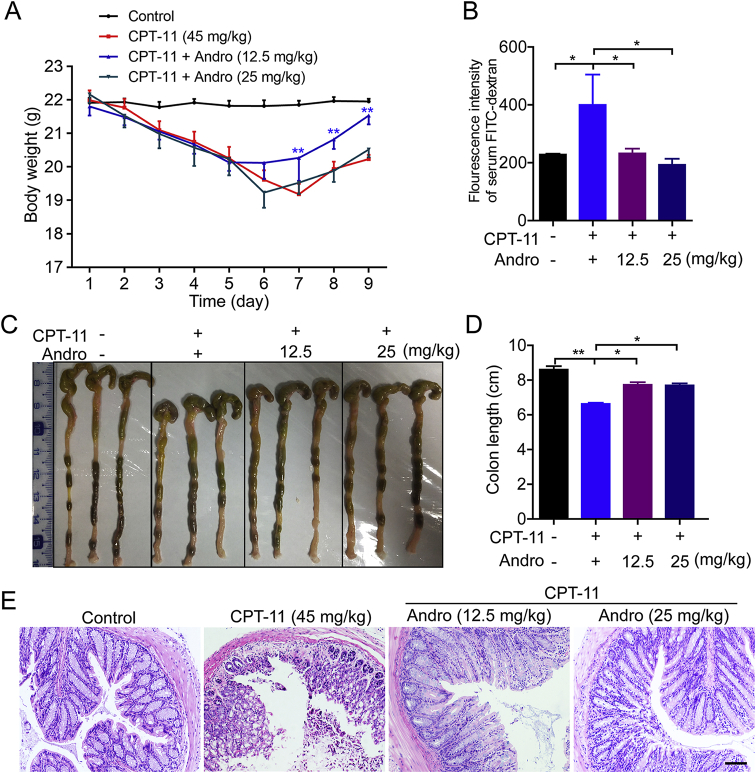

Although andrographolide did not enhance the tumor suppression effect of CPT-11, a significant improvement in intestinal mucositis caused by CPT-11 was observed after co-treatment with andrographolide. It was observed that CPT-11 exposure caused substantial body weight loss in mice. This weight loss was significantly ameliorated in the CPT-11 plus 25 mg/kg andrographolide treatment group compared to that in the CPT-11 group. All mice subsequently regained their weight when CPT-11 was stopped (Fig. 2A). After sacrificing the mice on Day 11, the colon lengths of mice treated with CPT-11 alone were shortened compared to those in the control group. Colon length shortening was inhibited when andrographolide was co-administered (Fig. 2B and C). To observe the damage to colon tissues in each group, the tissues were analyzed by H&E and IHC staining. Tissue damage was markedly happened in the villi and crypts in the CPT-11-treated mice, while the damage was reduced after andrographolide administration (Fig. 2D and E). As a marker of tight junction structure21,22, the distribution and expression of tight junction protein ZO-1 (ZO-1) were diminished by CPT-11, which was reversed by andrographolide (Fig. 2F). Furthermore, a “therapeutic” model was set up by CPT-11 on Days 1–4 and andrographolide was injected ip with doses of 12.5 or 25 mg/kg on Days 5–9. Administration of andrographolide after CPT-11 challenge also decreased the body weight loss (Fig. 3A) and colon damage (Fig. 3B‒E). The above findings suggest that andrographolide can all alleviate the colon damage triggered by CPT-11.

Figure 2.

Andrographolide prevented intestinal mucositis caused by CPT-11 in tumor-bearing mice. Tumor-bearing mice were treated with 45 mg/kg CPT-11 (ip) on Days 1–5 and 22.5 mg/kg on Days 6–8. Meanwhile, andrographolide was injected (ip, 12.5 and 25 mg/kg) on Days 1–10. (A) Body weight was recorded. (B) The colon was photographed. (C) Colon length was measured. (D) Representative images of the histopathology of the colon sections from tumor-bearing mice. (E, F) IHC staining and qualification of ZO-1 in colon tissues. Data are represented as mean ± SEM (n = 6 in each group). ∗P < 0.05. Scale bar: 100 μm.

Figure 3.

Andrographolide ameliorated intestinal mucositis caused by CPT-11. Mice were treated with 45 mg/kg CPT-11 (ip) only on Days 1–4. Andrographolide was injected (ip, 12.5 and 25 mg/kg) on Days 5–9 in groups III and group IV, respectively. (A) Body weight was recorded. (B) Effect of CPT-11 on intestinal permeability in vivo was examined. (C) The colon was photographed. (D) Colon length was measured. (E) Representative images of the histopathology of the colon sections. Data are represented as mean ± SEM (n = 6 in each group). ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01. Scale bar: 100 μm.

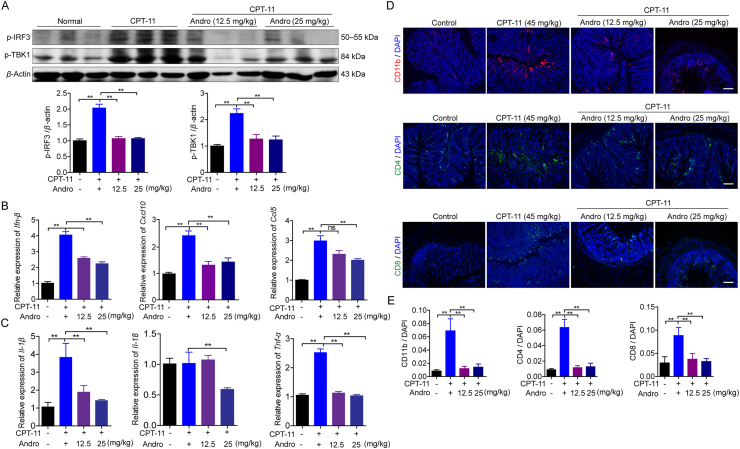

3.3. Andrographolide down-regulated CPT-11-induced cGAS‒STING signaling pathway in vivo

To further explore the effect of andrographolide on CPT-11-induced damage in vivo, the activation of the cGAS‒STING signaling pathway in colon tissues was examined. In the CPT-11 monotherapy group, protein levels of p-TBK-1 and p-IRF3 were markedly increased compared to those in the control group whereas this increase was strongly suppressed by andrographolide at either 12.5 or 25 mg/kg (Fig. 4A). The same trend was observed in the mRNA expression of cytokines downstream of cGAS–STING, such as Ifn-β, Cxcl10, and Ccl5 (Fig. 4B), as well as inflammatory cytokines, including Il-1β, Tnf-α, and Il-18 (Fig. 4C). Moreover, the increased infiltration of immunocytes, including CD11b, CD4, as well as CD8, was also inhibited by andrographolide treatment (Fig. 4D and E). These results suggest that andrographolide may exert its colon-protective actions via inhibition of the cGAS‒STING pathway activity.

Figure 4.

Andrographolide down-regulated CPT-11-induced activation of the cGAS‒STING pathway in vivo. (A) Western blot analysis of protein in cGAS‒STING signal pathway in colon tissues isolated from tumor-bearing mice treated with PBS, CPT-11 alone, or with andrographolide. (B, C) The relative expression level of Ifn-β, Cxcl10, and Ccl5 as well as Il-1β, Il-18, and Tnf-α in colon tissues. (D, E) Representative images and qualification of CD11b (red), CD4 (green), CD8 (green) immunostaining, and DAPI nuclear staining (blue) in colon tissues. Data are represented as mean ± SEM (n = 6 in each group). ∗∗P < 0.01.

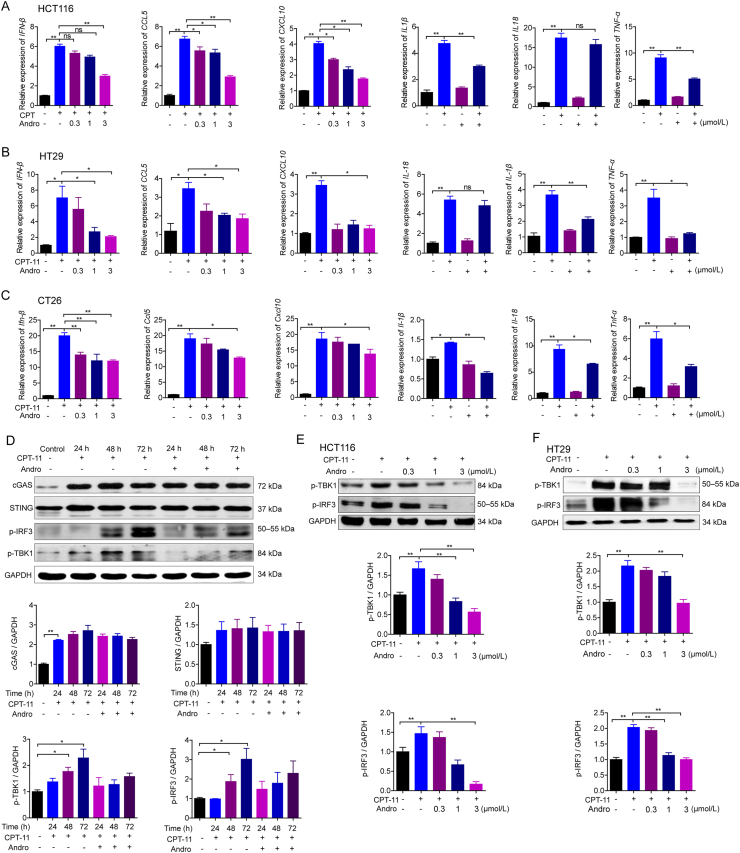

3.4. Andrographolide down-regulated CPT-11-induced cGAS‒STING signaling pathway in vitro

dsDNA can activate the cGAS‒STING‒TBK1‒IRF3 signaling to initiate IFN-β transcription23. Hence, we were interested in determining whether the same pathway is involved in dsDNA release stimulated by CPT-11. The mRNA expression levels of IFN-β, CXCL10, and CCL5 were enhanced in HCT116, CT26, and HT29 cells by CPT-11 as compared to the levels in the control at 24 h, which was significantly reduced following treatment with 3 μmol/L andrographolide (Fig. 5A‒C). In addition, the levels of p-TBK1 and p-IRF3 were time-dependently upregulated in HCT116 cells activated by 30 μmol/L CPT-11, and these were dramatically inhibited by 3 μmol/L andrographolide (Fig. 5D). Notably, p-TBK1 and p-IRF3 were dose-dependently reduced by andrographolide when HCT116 and HT29 cells were cultured with 30 μmol/L CPT-11 for 48 h (Fig. 5E and F). More importantly, the mRNA expression levels of inflammatory cytokines activated by CPT-11 were reduced after andrographolide treatment, such as TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-18 (Fig. 5A–C). In general, these findings imply that andrographolide was able to alleviate the cGAS‒STING‒TBK1‒IRF3 pathway activated by CPT-11, thus relieving intestinal mucositis caused by CPT-11 chemotherapy.

Figure 5.

Andrographolide down-regulated the CPT-11-induced activation of cGAS‒STING pathway in cancer cells. (A–C) HCT116, CT26, and HT29 were treated with CPT-11 (30 μmol/L) alone or with andrographolide for 24 h. Quantitative PCR analysis of downstream cytokines of cGAS‒STING, including IFN-β, CXCL10, and CCL5, respectively. (D) HCT116 cells were treated with CPT-11 (30 μmol/L) for the indicated time alone or with andrographolide (3 μmol/L). Expression of protein related to cGAS‒STING signal pathway were examined. (E, F) Western blot analysis of p-TBK1 and p-IRF3 in HCT116 and HT29 cells with CPT-11 (30 μmol/L) alone or with andrographolide for 24 h. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM (n = 3). ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01.

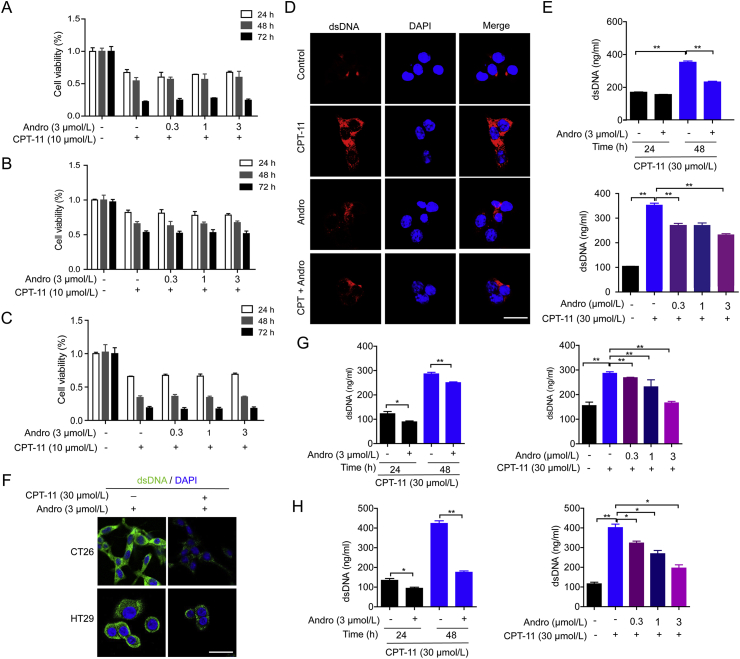

3.5. Andrographolide inhibited CPT-11-induced dsDNA release in vitro

To evaluate whether andrographolide could affect CPT-11-induced cytotoxic effects in vitro, the cytotoxic effect of CPT-11, alone and in combination with andrographolide, on HCT116, CT26, and HT29 cells at 24, 48, and 72 h was detected by CCK-8. Andrographolide did not increase the cytotoxic effect of CPT-11 at concentrations less than or equal to 3 μmol/L (Fig. 6A‒C). Next, we examined dsDNA release in intestinal epithelial cells in the cytoplasm and supernatants treated with CPT-11 and andrographolide. IF monitoring revealed the level of dsDNA was upregulated by CPT-11 monotherapy and downregulated by co-treatment with CPT-11 and andrographolide (Fig. 6D). CPT-11-induced dsDNA release was decreased significantly at 48 h with 3 μmol/L andrographolide using the PicoGreen assay (Fig. 6E), which was also observed in CT26 and HT29 cells (Fig. 6F‒H). These data indicated that andrographolide relieved DNA damage caused by CPT-11 in cells.

Figure 6.

Andrographolide inhibited CPT-11-induced dsDNA release in intestinal epithelial cells. (A–C) HCT116, CT26, and HT29 were treated with CPT-11 (30 μmol/L) alone or with andrographolide for the indicated time. Cell viability was detected by CCK-8. (D) HCT116 cells were treated with CPT-11 and/or andrographolide for 24 h, dsDNA (red) in the cells were analyzed by IF. (E) HCT116 were treated with CPT-11 (30 μmol/L) and andrographolide for the indicated time and dose. Concentrations of dsDNA in the culture medium of were examined. (F) CT26 and HT29 cells were treated with CPT-11 (30 μmol/L) and andrographolide (3 μmol/L) for 24 h and dsDNA (green) in the cells were analyzed by IF. (G, H) CT26 and HT29 were treated with CPT-11 (30 μmol/L) and andrographolide (3 μmol/L) for the indicated time and dose. Concentrations of dsDNA in the culture medium of were examined. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM (n = 3). ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01. Scale bar: 100 μm.

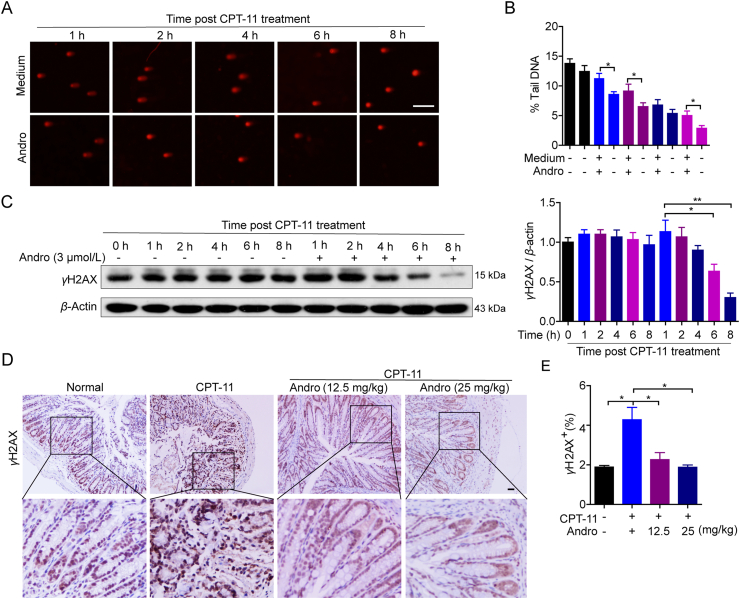

3.6. Andrographolide accelerated DNA damage repair triggered by CPT-11

To confirm whether andrographolide affects DNA damage induced by CPT-1124 in HCT116 cells, cells were incubated with CPT-11 (30 μmol/L) for 24 h and then with 3 μmol/L andrographolide for 1, 2, 4, 6, and 8 h. Then the comet assay was conducted to measure DSBs. The reduced tail length of DNA in the andrographolide-treated group revealed that repair of DSBs was advanced compared to that in the medium-treated group, and DNA damage was almost repaired at 8 h post CPT-11 stimulation (Fig. 7A and B). Western blot analysis showed that andrographolide treatment downregulated the level of γH2AX at 4 h and almost decreased to null at 8 h (Fig. 7C). In vivo, IHC analysis showed a sharp increase of γH2AX-positive cells in colon tissues in the CPT-11 monotherapy group, which was downregulated almost to normal by co-therapy with CPT-11 and andrographolide (Fig. 7D and E). In summary, these data suggest that andrographolide could protect colon tissue from damage induced by CPT-11 chemotherapy by promoting DNA damage repair.

Figure 7.

Andrographolide accelerated DNA damage‒repair in vitro and in vivo. (A–C) HCT116 were treated with CPT-11 (30 μmol/L) for 24 h and withdraw. Then the cells were cultured with or without andrographolide (3 μmol/L) for the indicated time. Comet assay were done to examine the DNA damage (A, B) and Western blot for expression γH2AX (C). (D, E) Representative IHC images and quantification of γH2AX-positive stain in colon tissues from tumor-bearing mice. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM (n = 3). ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01. Scale bar: 100 μm.

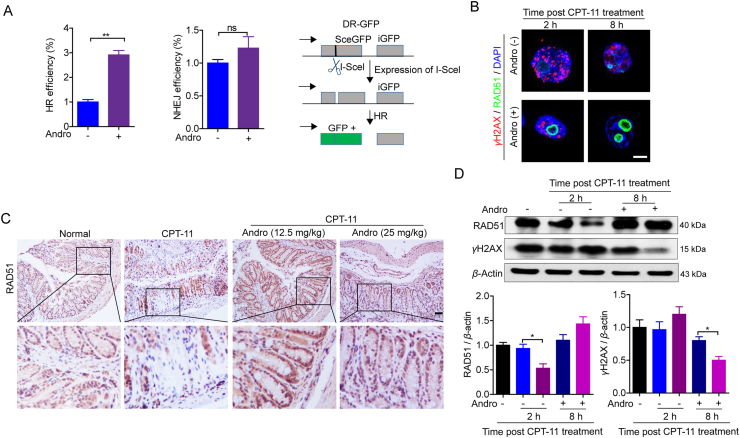

3.7. Andrographolide improved the HR-mediated DNA damage repair

It is known that DNA DSBs damage are repaired mainly via NHEJ and HR18,19,25,26. To identify the DSB repair pathway altered by andrographolide, a site-specific DSB induced by the I-SceI endonuclease using direct repeat-GFP (DR-GFP) and the total-NHEJ-GFP reporter systems for HR and NHEJ were employed. Andrographolide significantly promoted HR, but not NHEJ (Fig. 8A). Moreover, the recruitment of one critical HR factor, RAD51, to DSB foci in response to DNA damage caused by CPT-11 was significantly promoted after andrographolide treatment (Fig. 8B), which is consistent with the favorable role of andrographolide in homologous HR. Finally, it is interesting that andrographolide was shown to increase the RAD51 expression both in vivo and in vitro (Fig. 8C and D). These results indicate that andrographolide decreases dsDNA production by accelerating HR repair.

Figure 8.

Andrographolide improved homologous recombination pathway mediated DNA damage repair. (A) HCT116 cells (5 × 105) were seeded in 6-well plates co-transfected with 2 μg I-SceI expression plasmid (pCBASce) and either 4 μg pimEJ5-GFP or pHPRT-DR-GFP plasmid. Twenty-four hours post transfection, cells were incubated with andrographolide (3 μmol/L) for another 24 h. Cells were harvested and analyzed by flow cytometry analysis for GFP expression. (B, C) HCT116 were treated with CPT-11 (30 μmol/L) for 24 h and withdraw. Then the cells were cultured with or without andrographolide (3 μmol/L) for the indicated time. The cells were subjected to IF analysis for RAD51 and γH2AX foci (B) and Western blot for expression of RAD51 and γH2AX (C). (D) IHC staining of RAD51 in colon tissues resected from tumor-bearing mice. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM (n = 3). ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01. Scale bar: 100 μm.

4. Conclusions and discussion

The occurrence of mucosal damage manifested as diarrhea and enteritis is one of obstacles for the treatment of cancer patients with CPT-11. Novel agents for relieving these side effects are required. In this study, we verified that andrographolide exhibited an appreciable effect in protecting the damaged colon tissue from chemotherapy by promoting DNA repair mediated by HR and downregulating the cGAS‒STING pathway.

As a natural diterpenoid, andrographolide was shown to suppress tumor growth in mice (approximately 200 mg/kg)27. Andrographolide enhanced 5-FU-induced hepatocellular carcinoma apoptosis in a caspase-8-dependent manner12. Our previous study pointed out that andrographolide elevated 5-FU sensitivity in 5-FU resistant HCT116 cells by elevating BAX expression13. In this study, andrographolide did not enhance the efficacy of CPT-11 in tumor-bearing mice at low doses (12.5 and 25 mg/kg) in vivo. However, a significant protective effect against CPT-11 induced intestinal mucosal injury was observed after andrographolide co-treatment in vivo. Nevertheless, this activity by andrographolide may prolong the treatment duration, as the common side effect resolved can improve drug tolerance in patients.

Traditionally, the DNA damage response (DDR) is thought to mainly affect genome integrity and cell fate, and accumulating evidence suggests that genomic instability has impact on the inflammatory response, which was connected with aberrant activation of the cGAS‒STING pathway28. In Aicardi‒Goutières syndrome, cGAS‒STING pathway and chronic IFN signaling are excessively activated in mouse models deficient in nuclear DNA damage relative genes such as Trex129 or RNase H218. Importantly, cGAS‒STING is considerably stimulated in the mucosa of patients with inflammatory bowel diseases30. In our study, dsDNA caused by CPT-11 accumulated in the cytosol and released into the extracellular space, which was sensed by cGAS in intestinal epithelial cells themselves, causing the activation of the IRF3 and upregulation of inflammatory cytokines in vitro and in vivo. This mechanism is different from a previous report that CPT-11 induced intestinal inflammatory responses are mediated by absent in melanoma 2 (AIM2) inflammasome activation in macrophages3. Importantly, the activation of cGAS‒STING pathway both in CPT-11 treated mice and colonic epithelial cells were inhibited by andrographolide. This action was shown to contribute to the relief of CPT-11-induced intestinal mucositis. As a widely reported anti-inflammatory natural product, andrographolide has been shown to attenuate inflammation by inhibiting activation and function of macrophages31, 32, 33, 34. For example, by inhibiting the NLR family pyrin domain containing 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome in macrophages, andrographolide alleviates colitis and prevents colitis-associated cancer14. However, the effect of andrographolide on colonic epithelial cells has not yet been explored. A recent study showed that andrographolide could ameliorate chronic colitis by decreasing intestinal fibrosis21, suggesting that colonic epithelial cells may also be the target of andrographolide. Here, inhibition of the cGAS‒STING pathway in CPT-11 chemotherapy induced colonic epithelial damage was shown to be a new mechanism for andrographolide.

As dysregulation of the DDR and the immune system are at the core of many human afflictions35, 36, 37, the regulation of DNA damage repair plays an indispensable role in disease determination. A previous study revealed that the inhibition of nucleus translocation of cGAS could resume HR by interrupting the interactions between cGAS and proteins involved in DNA repair, including poly ADP-ribose polymerase 1 (PARP1) and H2AX18. Moreover, by compacting bound dsDNA, cGAS prevented the amenable to invasion by RAD51, which also inhibited HR DNA repair25. RAD51 plays a central role in DSB repair and replication fork processing while defects of which triggers a STING-dependent immune response38,39. In our study, andrographolide improved the HR pathway of DNA damage in HCT116 cells via elevating protein levels of RAD51 both in vitro and in vivo. Accordingly, restoration of RAD51 expression by andrographolide could inhibit the dsDNA-mediated STING activation. Our data suggest that the regulation of RAD51 might be a novel strategy for DNA damage-triggered inflammation. Thus, further research focusing on the mechanism by which andrographolide regulates RAD51 expression is required.

In summary, we demonstrated that DNA damage-induced cGAS‒STING pathway activation plays a pivotal role in mucosal damage induced by CPT-11, and that andrographolide could accelerate HR of repair and downregulate cGAS‒STING thereby improved chemotherapeutic outcome. It has been reported that CPT-11 could activate NLRP3 inflammasome through JNK and NF-κB signaling in macrophage2 and AIM2 inflammasome via “self-DNA” released from colonic epithelial cells3. Andrographolide-driven mitophagy mediated NLRP3 inflammasome inhibition has significant alleviation effect on colitis14. All these effects of andrographolide were investigated on macrophages. And reports have showed that andrographolide could affect various cells or signaling pathway in different disease40,41. Although it is difficult to rule out other effects of andrographolide on macrophage or T or other cells involved in its improvement on CPT-11-induced damage in vivo, the study here found out the effect of andrographolide on CPT-11-induced damage on colonic epithelial cells in vitro and in vivo as no studies was reported before from this point of view. As probed by andrographolide in this study, we found that promotion of DNA damage repair as well as downregulation of cGAS‒STING pathway activation in colonic epithelial cells services for the relief of CPT-11-induced intestinal mucositis. On one side, this investigation provided scientific support for clinical use of andrographolide or other cGAS–STING inhibitors with CPT-11. On the other side, our study here suggested a direction for andrographolide structure optimization by working on the phenotype including HR promotion or cGAS–STING inhibition.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (81871944, 81572389, 81922067), Jiangsu 333 project (BRA2016517, China), Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (BK20190306, China), Jiangsu Province Key Medical Talents (ZDRCA2016026, China), and Priority Academic Program Development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions and Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (14380114, China).

Author contributions

Wen Liu, Yanhong Gu, and Wenjie Guo conceived this project and designed the study. Yuanyuan Wang, Bin Wei, and Jianhua Gao performed the experiments and analyzed the data. Danping Wang, Haiqing Zhong, Jingjing Wu, Yang Sun, and Qiang Xu gave methodological support and conceptual advice. Wenjie Guo and Yuanyuan Wang wrote the manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Chinese Pharmaceutical Association and Institute of Materia Medica, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences.

Contributor Information

Wen Liu, Email: liuwen1849@126.com.

Yanhong Gu, Email: guyhphd@163.com.

Wenjie Guo, Email: guowj@nju.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Markman M. Chemotherapy: topotecan or treosulfan—that is the question. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2009;6:559–560. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2009.144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li Q., Zhang X., Wang W., Li L., Xu Q., Wu X., et al. CPT-11 activates NLRP3 inflammasome through JNK and NF-κB signalings. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2015;289:133–141. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2015.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lian Q., Xu J., Yan S., Huang M., Ding H., Sun X., et al. Chemotherapy-induced intestinal inflammatory responses are mediated by exosome secretion of double-strand DNA via AIM2 inflammasome activation. Cell Res. 2017;27:784–800. doi: 10.1038/cr.2017.54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alagoz M., Gilbert D.C., El-Khamisy S., Chalmers A.J. DNA repair and resistance to topoisomerase I inhibitors: mechanisms, biomarkers and therapeutic targets. Curr Med Chem. 2012;19:3874–3885. doi: 10.2174/092986712802002590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wu Y., Wei Q., Yu J. The cGAS/STING pathway: a sensor of senescence-associated DNA damage and trigger of inflammation in early age-related macular degeneration. Clin Interv Aging. 2019;14:1277–1283. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S200637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Motwani M., Pesiridis S., Fitzgerald K.A. DNA sensing by the cGAS–STING pathway in health and disease. Nat Rev Genet. 2019;20:657–674. doi: 10.1038/s41576-019-0151-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ahn J., Gutman D., Saijo S., Barber G.N. STING manifests self DNA-dependent inflammatory disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:19386–19391. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1215006109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.An J., Durcan L., Karr R.M., Briggs T.A., Rice G.I., Teal T.H., et al. Expression of cyclic GMP-AMP synthase in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017;69:800–807. doi: 10.1002/art.40002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kerur N., Fukuda S., Banerjee D., Kim Y., Fu D., Apicella I., et al. cGAS drives noncanonical-inflammasome activation in age-related macular degeneration. Nat Med. 2018;24:50–61. doi: 10.1038/nm.4450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xia Y.F., Ye B.Q., Li Y.D., Wang J.G., He X.J., Lin X., et al. Andrographolide attenuates inflammation by inhibition of NF-κB activation through covalent modification of reduced cysteine 62 of p50. J Immunol. 2004;173:4207–4217. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.6.4207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Peng S., Hang N., Liu W., Guo W., Jiang C., Yang X., et al. Andrographolide sulfonate ameliorates lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury in mice by down-regulating MAPK and NF-κB pathways. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2016;6:205–211. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2016.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yang L., Wu D., Luo K., Wu S., Wu P. Andrographolide enhances 5-fluorouracil-induced apoptosis via caspase-8-dependent mitochondrial pathway involving p53 participation in hepatocellular carcinoma (SMMC-7721) cells. Cancer Lett. 2009;276:180–188. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang W., Guo W., Li L., Fu Z., Liu W., Gao J., et al. Andrographolide reversed 5-FU resistance in human colorectal cancer by elevating BAX expression. Biochem Pharmacol. 2016;121:8–17. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2016.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guo W., Sun Y., Liu W., Wu X., Guo L., Cai P., et al. Small molecule-driven mitophagy-mediated NLRP3 inflammasome inhibition is responsible for the prevention of colitis-associated cancer. Autophagy. 2014;10:972–985. doi: 10.4161/auto.28374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu W., Guo W., Guo L., Gu Y., Cai P., Xie N., et al. Andrographolide sulfonate ameliorates experimental colitis in mice by inhibiting Th1/Th17 response. Int Immunopharmacol. 2014;20:337–345. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2014.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhao M., Guo W., Wu Y., Yang C., Zhong L., Deng G., et al. SHP2 inhibition triggers anti-tumor immunity and synergizes with PD-1 blockade. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2019;9:304–315. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2018.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mi Y., Gurumurthy R.K., Zadora P.K., Meyer T.F., Chumduri C. Chlamydia trachomatis inhibits homologous recombination repair of DNA breaks by interfering with PP2A signaling. mBio. 2018;9 doi: 10.1128/mBio.01465-18. e01465-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pierce A.J., Johnson R.D., Thompson L.H., Jasin M. XRCC3 promotes homology-directed repair of DNA damage in mammalian cells. Genes Dev. 1999;13:2633–2638. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.20.2633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bennardo N., Cheng A., Huang N., Stark J.M. Alternative-NHEJ is a mechanistically distinct pathway of mammalian chromosome break repair. PLoS Genet. 2008;4 doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li H., Fan C., Lu H., Feng C., He P., Yang X., et al. Protective role of berberine on ulcerative colitis through modulating enteric glial cells-intestinal epithelial cells-immune cells interactions. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2020;10:447–461. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2019.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gao J., Cui J., Zhong H., Li Y., Liu W., Jiao C., et al. Andrographolide sulfonate ameliorates chronic colitis induced by TNBS in mice via decreasing inflammation and fibrosis. Int Immunopharmacol. 2020;83:106426. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2020.106426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lin J.C., Wu J.Q., Wang F., Tang F.Y., Sun J., Xu B., et al. QingBai decoction regulates intestinal permeability of dextran sulphate sodium-induced colitis through the modulation of notch and NF-κB signalling. Cell Prolif. 2019;52:e12547. doi: 10.1111/cpr.12547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ruangkiattikul N., Nerlich A., Abdissa K., Lienenklaus S., Suwandi A., Janze N., et al. cGAS–STING–TBK1–IRF3/7 induced interferon-β contributes to the clearing of non tuberculous mycobacterial infection in mice. Virulence. 2017;8:1303–1315. doi: 10.1080/21505594.2017.1321191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wood J.P., Smith A.J., Bowman K.J., Thomas A.L., Jones G.D. Comet assay measures of DNA damage as biomarkers of irinotecan response in colorectal cancer in vitro and in vivo. Cancer Med. 2015;4:1309–1321. doi: 10.1002/cam4.477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jiang H., Xue X., Panda S., Kawale A., Hooy R.M., Liang F., et al. Chromatin-bound cGAS is an inhibitor of DNA repair and hence accelerates genome destabilization and cell death. EMBO J. 2019;38 doi: 10.15252/embj.2019102718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu H., Zhang H., Wu X., Ma D., Wu J., Wang L., et al. Nuclear cGAS suppresses DNA repair and promotes tumorigenesis. Nature. 2018;563:131–136. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0629-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rajagopal S., Kumar R.A., Deevi D.S., Satyanarayana C., Rajagopalan R. Andrographolide, a potential cancer therapeutic agent isolated from Andrographis paniculata. J Exp Ther Oncol. 2003;3:147–158. doi: 10.1046/j.1359-4117.2003.01090.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li T., Chen Z.J. The cGAS–cGAMP–STING pathway connects DNA damage to inflammation, senescence, and cancer. J Exp Med. 2018;215:1287–1299. doi: 10.1084/jem.20180139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gray E.E., Treuting P.M., Woodward J.J., Stetson D.B. Cutting edge: cGAS is required for lethal autoimmune disease in the Trex1-deficient mouse model of Aicardi–Goutières syndrome. J Immunol. 2015;195:1939–1943. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1500969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu S., Zhang Y., Ren J., Li J. Microbial DNA recognition by cGAS–STING and other sensors in dendritic cells in inflammatory bowel diseases. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2015;21:901–911. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liao W., Tan W.S., Wong W.S. Andrographolide restores steroid sensitivity to block lipopolysaccharide/IFN-γ-induced IL-27 and airway hyperresponsiveness in mice. J Immunol. 2016;196:4706–4712. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1502114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ren Y.Q., Zhou Y.B. Inhibition of andrographolide in RAW 264.7 murine macrophage osteoclastogenesis by downregulating the nuclear factor-kappaB signaling pathway. Genet Mol Res. 2015;14:15955–15961. doi: 10.4238/2015.December.7.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gao J., Peng S., Shan X., Deng G., Shen L., Sun J., et al. Inhibition of AIM2 inflammasome-mediated pyroptosis by andrographolide contributes to amelioration of radiation-induced lung inflammation and fibrosis. Cell Death Dis. 2019;10:957. doi: 10.1038/s41419-019-2195-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kim N., Lertnimitphun P., Jiang Y., Tan H., Zhou H., Lu Y., et al. Andrographolide inhibits inflammatory responses in LPS-stimulated macrophages and murine acute colitis through activating AMPK. Biochem Pharmacol. 2019;170:113646. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2019.113646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kang C., Xu Q., Martin T.D., Li M.Z., Demaria M., Aron L., et al. The DNA damage response induces inflammation and senescence by inhibiting autophagy of GATA4. Science. 2015;349:aaa5612. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa5612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Meira L.B., Bugni J.M., Green S.L., Lee C.W., Pang B., Borenshtein D., et al. DNA damage induced by chronic inflammation contributes to colon carcinogenesis in mice. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:2516–2525. doi: 10.1172/JCI35073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Praveen Kumar M.K., Shyama S.K., Sonaye B.S., Naik U.R., Kadam S.B., Bipin P.D., et al. Evaluation of γ-radiation-induced DNA damage in two species of bivalves and their relative sensitivity using comet assay. Aquat Toxicol. 2014;150:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.aquatox.2014.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bhat K.P., Cortez D. RPA and RAD51: fork reversal, fork protection, and genome stability. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2018;25:446–453. doi: 10.1038/s41594-018-0075-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bhattacharya S., Srinivasan K., Abdisalaam S., Su F., Raj P., Dozmoro I v, et al. RAD51 interconnects between DNA replication, DNA repair and immunity. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:4590–4605. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tan W.S.D., Liao W., Zhou S., Wong W.S.F. Is there a future for andrographolide to be an anti-inflammatory drug? Deciphering its major mechanisms of action. Biochem Pharmacol. 2017;139:71–81. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2017.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yang C.H., Yen T.L., Hsu C.Y., Thomas P.A., Sheu J.R., Jayakumar T. Multi-targeting andrographolide, a novel NF-κB inhibitor, as a potential therapeutic agent for stroke. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18:1638. doi: 10.3390/ijms18081638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]