Abstract

Background

The incidence of early-onset colorectal cancer (EOCRC) is increasing at an alarming rate and further studies are needed to identify risk factors and to develop prevention strategies.

Methods

Risk factors significantly associated with EOCRC were identified using meta-analysis. An individual risk appraisal model was constructed using the Rothman–Keller model. Next, a group of random data sets was generated using the binomial distribution function method, to determine nodes of risk assessment levels and to identify low, medium, and high risk populations.

Results

A total of 32,843 EOCRC patients were identified in this study, and nine significant risk factors were identified using meta-analysis, including male sex, Caucasian ethnicity, sedentary lifestyle, inflammatory bowel disease, and high intake of red meat and processed meat. After simulating the risk assessment data of 10,000 subjects, scores of 0 to 0.0018, 0.0018 to 0.0036, and 0.0036 or more were respectively considered as low-, moderate-, and high-risk populations for the EOCRC population based on risk trends from the Rothman–Keller model.

Conclusion

This model can be used for screening of young adults to predict high risk of EOCRC and will contribute to the primary prevention strategies and the reduction of risk of developing EOCRC.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12885-022-09238-4.

Keywords: Early-onset colorectal cancer, Risk factors, Meta-analysis, Rothman–Keller model, Risk assessment

Background

Although the incidence of colorectal cancer (CRC) has declined with the support of medical technology and prevention policies, a completely opposite trend has been observed in young adults under the age of 50 years [1, 2]. Early-onset colorectal cancer (EOCRC) is defined as colorectal cancer diagnosed before the age of 50 years, and has shown a progressively increasing incidence worldwide. Studies have reported that approximately 11% of CRC cases registered in the National Cancer Database were diagnosed in adults aged 18 to 49 years [3]. Similarly, recent data from Europe indicate that the incidence of CRC increased by 7.9, 4.9, and 1.6% per year among subjects aged 20–29, 30–39, and 40–49 years from 2004 to 2016, respectively [4]. Most cases of EOCRC are diagnosed after the onset of symptoms, which include bloody stool and abdominalgia, increasing the danger of delayed diagnosis and poor prognosis [5, 6].

The causes of the rising incidence of EOCRC have not been fully elucidated. The majority of EOCRC cases are disseminated and may be associated with changes in environmental, behavioral, and dietary patterns. Several studies have reported an increased risk of EOCRC from alcohol consumption, sedentary lifestyle, and high intake of red and processed meats [7–10]. In addition, lower levels of schooling may also increase the prevalence of EOCRC [7, 11]. Primary prevention is a key strategy to reduce the burden of this disease. The American Cancer Society has lowered the age of screening for people at risk of colorectal cancer from 50 to 45 years of age [12]. Studies demonstrate that increasing participation in population-based risk screening not only reduces mortality but also reduces health care costs [13]. Therefore, it is important to identify risk factors for EOCRC. Previous meta-analyses have identified risk factors such as family history of CRC, male sex, and obesity. However, there are still other factors that have revealed non-significant associations due to small sample sizes with insufficient statistical power [14, 15]. Due to the needs of large-scale population screening, it is essential to build an individualized risk prediction and evaluation model, which can help evaluate and identify high-risk populations for EOCRC. Previous studies have found that individualized risk-based screening is more likely to be accepted [16].

Accordingly, we established the EOCRC risk appraisal and prediction system using the Rothman–Keller model, aiming at early and effective identification of high-risk populations of EOCRC. Our scoring system also provides easy risk prediction formulas for individuals to achieve potential risk reduction.

Methods

Search strategy and study selection

Based on a previously published meta-analysis [14], we conducted a comprehensive search in PubMed and the Web of Science (WOS) to discover new original studies using the following terms: “colorectal cancer,” “colorectal neoplasms,” “colon tumor,” “rectum tumor,” “colon cancer,” “rectum cancer,” “early onset,” “young onset,” “young adult”, “age of 50”, “risk”. Multiple combinations of the above search terms were used. Studies that met the following criteria were considered: i) Diagnosis consistent with EOCRC, ii) cohort studies or case-control studies, and iii) control group age-matched with non-EOCRC patients of the case group. Only studies published in English were considered. Literature management and review was performed using Endnote × 9 (V9.3.3, Clarivate Analytics) [17]. References that met the inclusion criteria were manually screened to avoid omissions. Reviews, case reports, experimental studies, duplicate publications, and studies that did not meet the diagnosis of EOCRC were excluded. The titles, abstracts, and subsequent full text of the retrieved publications were screened by two independent reviewers. A third reviewer decided on any disagreements.

Data extraction

Baseline data were collected from all patients, including sex, race, past medical history (diabetes, inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), hyperlipidemia, hypertension), dietary factors (processed meat, red meat), lifestyle habits (sedentary, obesity, alcohol intake, smoking, dessert), and medication history (aspirin and NSAIDs). Screening of risk factors for EOCRC was derived from meta-analysis and the factors that significantly correlated with EOCRC (P < 0.05) were included in subsequent model construction.

Construction of the risk appraisal model

The Rothman–Keller model was used to construct an individualized risk appraisal model for EOCRC [18]. It was first applied in 1972 to assess the effects of alcohol and tobacco on the risk of oral and laryngeal cancers. It considers both independent and interactive effects of influencing factors and has been applied in the risk assessment and prevention of a multitude of chronic diseases [19]. The relative ratio (RR) can be replaced by the odds ratios (OR) when the outcome occurs in less than 10% [20, 21]. The computational procedure of Rothman–Keller model is as follows:

-

(I)

Population attributable risk percentage (PAR%)

-

(II)

Baseline incidence ratio (ρ)

Pi: the proportion of individuals exposed to a risk factor in the overall population; RRi: the relative risk of exposure to a risk factor.

-

(III)

Risk score (S) and combined risk score (θ)

Mi: risk factor scores for S ≥ 1; Ni: risk factor scores for S < 1

-

(IV)

Individual risk prediction score of EOCRC (I)

QEOCRC: The incidence of EOCRC.

Statistical analysis

We performed sensitivity analysis on variables that were significant. Only variables that showed significance (P < 0.05) in the fixed-effects model combined with the random-effects model were considered stable. These eligible variables were then included in the risk scoring system. Variables that exhibit significance in only one model will be excluded from the risk system since they were considered to be unstable [19]. The risk of publication bias was calculated using Egger’s test. Simulated data of 10,000 subjects were randomly generated using the binomial distribution function method. The individual risk prediction scores of EOCRC (I) were calculated after substitution of the simulated data into the Rothman–Keller model. Statistical analysis was performed using STATA 15.1 software (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX, USA) and RStudio software (version 1.4).

Results

Literature selection

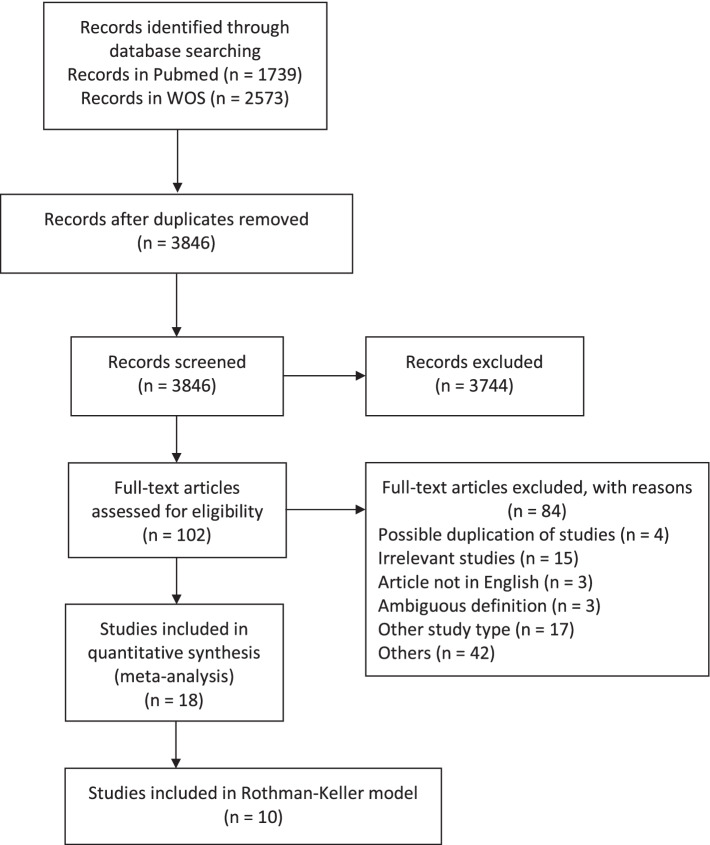

The literature search identified 4312 publications, of which 3846 were unique studies. A total of 3744 publications were excluded because they did not meet the inclusion criteria. After screening the full text of the remaining 102 studies, 18 articles were included in the meta-analysis, four of which were new compared to the previously published meta-analysis. Ten studies were used for the construction of the risk appraisal model as they provided baseline data of case and control groups, containing a total of 32,843 cases and 25,806,408 controls. Figure 1 shows the flow chart of the study selection and identification.

Fig. 1.

The flow chart of the study selection and identification

Risk factors for EOCRC

As shown in Table 1, based on the combined ORs and P-values, we identified nine core risk factors influencing the development of EOCRC, namely male sex, Caucasian ethnicity, family history of CRC, sedentary behavior, alcohol intake, obesity, diabetes, IBD, and high intake of red meat. However, the use of NSAIDs or aspirin and high intake of dessert were excluded due to the lack of sufficient studies (n = 2). The results of the fixed-effects and random-effects models showed that the joint effect of smoking, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and educational level was unstable (P for fixed-effects model < 0.05 while P for random-effects model > 0.05). Thus, these factors were excluded in the Rothman–Keller model. In addition, although high intake of processed meat did not show a significant association in the meta-analysis, it was included in the construction of the prediction model as a potential factor for EOCRC because it showed a significant trend (OR = 1.24, 95% CI = 0.99–1.55). No publication bias was found using Egger’s test (P>0.05).

Table 1.

Results of the combined assessment of various risk factors

| Risk factors | No.a | Cases, n Exposure (+/−) | Controls, n Exposure (+/−) | Reference for data mining | Fixed effect model | Random effects model | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95%CI | P | OR | 95%CI | P | |||||

| Male sex | 9 | 8533/8073 | 5,013,326/6,907,255 | [7, 9, 22–27] | ||||||

| Yes | 1.16 | 1.12–1.20 | 0.001 | 1.18 | 1.02–1.37 | 0.031 | ||||

| No | 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| Caucasian ethnicity | 6 | 16,790/7037 | 15,145,866/10,614,153 | [8, 22–25, 27] | ||||||

| Yes | 1.77 | 1.72–1.83 | 0.001 | 1.41 | 1.16–1.73 | 0.001 | ||||

| No | 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| Family history of CRC | 9 | 2350/8496 | 308,951/11,502,258 | [7, 9, 22, 23, 25, 27] | ||||||

| Yes | 7.03 | 6.67–7.41 | 0.001 | 4.13 | 1.68–10.13 | 0.002 | ||||

| No | 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| Sedentary | 5 | 294/1167 | 592/3175 | [7, 9, 23, 28] | ||||||

| Yes | 1.26 | 1.06–1.48 | 0.007 | 1.33 | 1.05–1.70 | 0.02 | ||||

| No | 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| Smoking | 9 | 10,860/16,576 | 8,367,277/17,375,989 | [7, 8, 22–25, 27, 28] | ||||||

| Yes | 1.44 | 1.40–1.47 | 0.001 | 1.23 | 0.93–1.64 | 0.039 | ||||

| No | 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| Alcoholb | 5 | 2852/5403 | 2,833,801/8,971,210 | [7, 9, 23, 27, 28] | ||||||

| Yes | 1.66 | 1.58–1.75 | 0.001 | 1.52 | 1.28–1.80 | 0.001 | ||||

| No | 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| Obesity | 10 | 12,195/15,887 | 8,114,710/17,676,715 | [8, 22–24, 26, 27] | ||||||

| Yes | 2.30 | 2.25–2.36 | 0.001 | 1.42 | 1.13–1.78 | 0.003 | ||||

| No | 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| Hypertension | 5 | 4794/22,980 | 2,886,828/22,846,354 | [8, 22, 25–27] | ||||||

| Yes | 1.49 | 1.44–1.54 | 0.001 | 1.36 | 0.84–2.21 | 0.213 | ||||

| No | 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| Hyperlipidemia | 5 | 5602/22,172 | 2,125,036/23,608,146 | [8, 22, 25–27] | ||||||

| Yes | 2.11 | 2.05–2.19 | 0.001 | 1.39 | 0.94–2.06 | 0.099 | ||||

| No | 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| Diabetes | 8 | 1663/25,143 | 494,375/13,511,324 | [7–9, 22–26] | ||||||

| Yes | 1.47 | 1.39–1.55 | 0.001 | 1.25 | 1.04–1.50 | 0.019 | ||||

| No | 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| IBD | 3 | 936/9716 | 396,324/11,446,050 | [25–27] | ||||||

| Yes | 3.46 | 3.23–3.71 | 0.001 | 3.20 | 1.60–6.41 | 0.001 | ||||

| No | 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| Red meat | 3 | 1214/1081 | 1260/1945 | [7, 9, 23] | ||||||

| Yes | 1.12 | 1.07–1.17 | 0.001 | 1.12 | 1.07–1.17 | 0.001 | ||||

| No | 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| Processed meat | 4 | 658/573 | 872/1443 | [7, 9, 23, 28] | ||||||

| Yes | 1.10 | 1.03–1.19 | 0.007 | 1.24 | 0.99–1.55 | 0.064 | ||||

| No | 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| High school education | 4 | 1572/2705 | 2174/4441 | [7, 9, 23, 25] | ||||||

| Less | 1.14 | 1.09–1.20 | 0.001 | 1.49 | 0.78–2.87 | 0.230 | ||||

| More | 1 | 1 | ||||||||

aNumber of studies for meta-analysis

bPooled effect estimates to obtain the highest exposure defined category compared with the lowest

Parameters of the risk appraisal model

The proportion of exposed individuals in the control group was used as an estimate of the overall population exposure rate (Pi). The RR values (RRs) in the Rothman–Keller model were replaced by the combined OR values (ORi) from the meta-analysis. The parameters of the EOCRC risk appraisal model are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Risk assessment model parameters of EOCRC

| Risk factor | RRi | Pi | PAR% | ρ | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | |||||

| Yes | 1.18 | 0.4206 | 0.0704 | 0.9296 | 1.0970 |

| No | 1 | 0.5794 | 0.9296 | ||

| Caucasian ethnicity | |||||

| Yes | 1.41 | 0.5880 | 0.1942 | 0.8058 | 1.1361 |

| No | 1 | 0.4120 | 0.8058 | ||

| Family history of CRC | |||||

| Yes | 4.13 | 0.0262 | 0.0757 | 0.9243 | 3.8175 |

| No | 1 | 0.9738 | 0.9243 | ||

| Sedentary | |||||

| Yes | 1.33 | 0.1572 | 0.0493 | 0.9507 | 1.2644 |

| No | 1 | 0.8428 | 0.9507 | ||

| Alcohol | |||||

| Yes | 1.52 | 0.2401 | 0.1110 | 0.8890 | 1.3513 |

| No | 1 | 0.7599 | 0.8890 | ||

| Obesity | |||||

| Yes | 1.42 | 0.3146 | 0.1167 | 0.8833 | 1.2543 |

| No | 1 | 0.6854 | 0.8833 | ||

| Diabetes | |||||

| Yes | 1.25 | 0.0353 | 0.0087 | 0.9913 | 1.2391 |

| No | 1 | 0.9647 | 0.9913 | ||

| IBD | |||||

| Yes | 3.2 | 0.0335 | 0.0686 | 0.9314 | 2.9806 |

| No | 1 | 0.9665 | 0.9314 | ||

| Red meat | |||||

| Yes | 1.12 | 0.3931 | 0.0451 | 0.9549 | 1.0695 |

| No | 1 | 0.6069 | 0.9549 | ||

| Processed meat | |||||

| Yes | 1.24 | 0.3767 | 0.0829 | 0.9171 | 1.1372 |

| No | 1 | 0.6233 | 0.9171 | ||

Calculation of the EOCRC individualized risk assessment

Individualized combined risk scores (I) were calculated based on the parameters in Table 2 (Formula III and IV). For example, a male subject (subject A) younger than age 50 years (S = 1.0970), Caucasian (S = 1.1361), with a family history of CRC (S = 3.8175), history of alcohol consumption (S = 1.3513), diabetes (S = 1.2391), and high intake of red meat (S = 1.0685), but without the characteristics of IBD (S = 0.9314), sedentary lifestyle (S = 0.9507), obesity (S = 0.8833), and high intake of processed meat (S = 0.9171). Accordingly, the combined risk score (θ) of subject A = (1.0970–1) + (1.1361–1) + (3.8175–1) + (1.3513–1) + (1.2391–1) + (1.0685–1) + 0.9314 × 0.9507 × 0.8833 × 0.9171 = 4.427. A study based on the U.S. Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database reported a 0.12% prevalence of EOCRC [8]. Therefore, the individual risk prediction score of EOCRC (I) for subject A = 0.12% * 4.427 = 0.531%.

Level of EOCRC risk assessment

Figure 2 and Supplementary Table 1 show the individual risk scores of 10,000 simulated subjects sorted in ascending order. The 8795th (I = 0.0018, point A) and 9591st (I = 0.0036, point B) positions were selected as the nodes for the level of EOCRC risk assessment. Individual risk prediction scores (I) of 0 to 0.0018, 0.0018 to 0.0036, and 0.0036 or higher were considered low, medium, or high risk. Accordingly, Subject A was in a high-risk group, and we strongly recommend that he should receive health education and clinical screening.

Fig. 2.

The predictive analysis of Rothman–Keller model for EOCRC

Discussion

Although CRC is still relatively rare in the younger aged population (0.12%), the alarming increasing in EOCRC patients cannot be ignored [29, 30]. The clinical cases, molecular, and familial features of EOCRC strongly suggest that it may be a separate disease rather than a subset of CRC [31, 32]. It is estimated that there may be a 30–120% increase in young colorectal cancer patients by 2030 based on current trends [33]. In addition, most EOCRCs are insidious and have a worse prognosis compared to late-onset CRC, which undoubtedly increases the difficulty of diagnosis and disease prevention [34]. Although annual screening is strongly recommended for individuals with a family history of CRC in first-degree relatives, the lack of subjective knowledge about the high risks of CRC and the negative attitudes towards clinical screening are the main reasons why most young adults are reluctant to undergo screening, which undoubtedly increases the difficulty of primary prevention in high-risk groups [35, 36]. It is important to construct a risk assessment system based on clinical or behavioral factors. Previous studies have developed clinical prediction models based on colonoscopy or stool test results [37–39]. Although such tests identify a subset of patients that may benefit from them, most predictive tools require specialized assessment by clinicians and are not suitable for prospective population screening [40]. In addition, precise cancer screening or modified screening regimens based on risk-stratification may allow adults to benefit more from CRC screening than conventional age-based strategies [41]. Therefore, we prefer to build a risk prediction system in which subjects can independently participate, and contributes to encouraging young adults to screen for potential disease probability before visiting the clinic.

Compared to the previous meta-analysis [14], we identified significant associations between sedentary, IBD, diabetes, high intake of red meat and processed meat, and the development of EOCRC, as we included more original studies. Although the correlation between the high intake of processed meats and EOCRC was not statistically significant, the trend it exhibited was equally alarming [42]. The role of non-genetic factors, especially dietary factors, in the pathogenesis of EOCRC should not be ignored. Several studies have also reported a positive association between reduced intake of folate, fiber, citrus fruits, and greater risk of EOCRC [7, 9]. Unfortunately, most studies do not include regional factors as one of the variables, which prevents us from understanding the contribution of urban-rural or regional differences to the incidence of EOCRC, although this appears to be potentially relevant at present [43–45]. Our study constructed a more accurate model based on a meta-analysis that considered and quantified interactions among risk factors, providing a prediction system for individuals under the age of 50 years. In contrast to non-modifiable factors such as sex and race, most risk factors we identified were common and changeable behavioral factors, such as sedentary lifestyle, high intake of red meat and processed meat, and alcohol consumption. This means that young subjects who are alerted may reduce the incidence of EOCRC by modifying their diet or daily behavior patterns. As far as we know, most people appear to be more receptive to modifying their personal risk through diet and exercise [16]. Despite the prevalence of these factors among the general CRC population, we can still find some evidence on how these variables influence the development of EOCRC. It is well known that family history of cancer, obesity, sedentary lifestyle and high consumption of high calorie, high fat, high sucrose diet are the key factors in CRC [46]. The prevalence of obesity has increased in the USA, especially among young patients, which may play a role in reducing the age of CRC onset [33]. Similar problems exist in other countries [47, 48]. The prevalence of known risk factors such as diabetes, smoking, and alcohol consumption continues to rise [49–51], and these high-risk behaviors in young adults increase the incidence of EOCRC despite measures already in place to counter. Patients with longstanding IBD have a two to three times increased risk of CRC, especially when diagnosed at an early age [52]. Approximately 2–5% of the general CRC population is affected by hereditary cancer syndromes. However, this appears to be higher (22%) in patients diagnosed with EOCRC [2]. Besides, the increasing global prevalence of non-Mediterranean Western dietary patterns, characterized by a high intake of red and processed meats, among the young population has undoubtedly increased the burden of EOCRC [53]. Therefore, there is a significant need to enhance health education to control these potential risk factors.

This study had some limitations. First, although we generated a group of random data sets using a binomial distribution method, there is a lack of evidence supporting and validating results from multicenter, large-scale, and real-world studies. Second, studies on risk factors for EOCRC are still very limited and lead to the exclusion of other potential risk factors from the model construction due to insufficient statistical power.

Conclusions

We established a risk appraisal model for EOCRC based on meta-analysis and the Rothman–Keller model to provide personalized health education and screening for individuals with different risk levels, which can be used for primary prevention of CRC and to help reduce the incidence of EOCRC.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1. The individual risk scores of 10,000 simulated subjects.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- EOCRC

Early-onset colorectal cancer

- CRC

Colorectal cancer

- WOS

Web of Science

- SEER

Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database

Authors’ contributions

GJL and LY contributed to the concept, design, and writing of the manuscript. YJL, HM, and JY contributed to literature search, data acquisition, data analysis, and statistical analysis. HCH and LLC contributed to data acquisition, supervision, editing of the manuscript. HJG and WGL performed the manuscript review. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 82004288), Project of National Clinical Research Base of Traditional Chinese Medicine in Jiangsu Province (No. JD2019SZXYB04) and Jiangsu province TCM leading talent training project (No. SLJ0211).

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Jialin Gu and Yan Li equal first authors.

Contributor Information

Guoli Wei, Email: weiguoli1987@163.com.

Jiege Huo, Email: huojiege@jsatcm.com.

References

- 1.Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, Bray F. Global Cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(3):209–249. doi: 10.3322/caac.21660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mauri G, Sartore-Bianchi A, Russo AG, Marsoni S, Bardelli A, Siena S. Early-onset colorectal cancer in young individuals. Mol Oncol. 2019;13(2):109–131. doi: 10.1002/1878-0261.12417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Virostko J, Capasso A, Yankeelov TE, Goodgame B. Recent trends in the age at diagnosis of colorectal cancer in the US National Cancer Data Base, 2004-2015. Cancer. 2019;125(21):3828–3835. doi: 10.1002/cncr.32347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vuik FE, Nieuwenburg SA, Bardou M, Lansdorp-Vogelaar I, Dinis-Ribeiro M, Bento MJ, Zadnik V, Pellise M, Esteban L, Kaminski MF, et al. Increasing incidence of colorectal cancer in young adults in Europe over the last 25 years. Gut. 2019;68(10):1820–1826. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2018-317592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Myers EA, Feingold DL, Forde KA, Arnell T, Jang JH, Whelan RL. Colorectal cancer in patients under 50 years of age: a retrospective analysis of two institutions' experience. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19(34):5651–5657. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i34.5651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yeo H, Betel D, Abelson JS, Zheng XE, Yantiss R, Shah MA. Early-onset colorectal Cancer is distinct from traditional colorectal Cancer. Clin Colorectal Cancer. 2017;16(4):293–299 e296. doi: 10.1016/j.clcc.2017.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Archambault AN, Lin Y, Jeon J, Harrison TA, Bishop DT, Brenner H, Casey G, Chan AT, Chang-Claude J, Figueiredo JC, et al. Nongenetic determinants of risk for early-onset colorectal Cancer. JNCI Cancer Spectr. 2021;5(3):pkab029. doi: 10.1093/jncics/pkab029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Elangovan A, Skeans J, Landsman M, Ali SMJ, Elangovan AG, Kaelber DC, Sandhu DS, Cooper GS. Colorectal Cancer, age, and obesity-related comorbidities: a large database study. Dig Dis Sci. 2020;66(9):3156–3163. doi: 10.1007/s10620-020-06602-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rosato V, Bosetti C, Levi F, Polesel J, Zucchetto A, Negri E, La Vecchia C. Risk factors for young-onset colorectal cancer. Cancer Causes Control. 2013;24(2):335–341. doi: 10.1007/s10552-012-0119-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nguyen LH, Liu PH, Zheng X, Keum N, Zong X, Li X, Wu K, Fuchs CS, Ogino S, Ng K, et al. Sedentary behaviors, TV viewing time, and risk of young-onset colorectal Cancer. JNCI Cancer Spectr. 2018;2(4):pky073. doi: 10.1093/jncics/pky073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sondergaard G, Mortensen LH, Andersen AM, Andersen PK, Dalton SO, Osler M. Social inequality in breast, lung and colorectal cancers: a sibling approach. BMJ Open. 2013;3(3):e002114. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-002114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fedewa SA, Siegel RL, Goding Sauer A, Bandi P, Jemal A. Colorectal cancer screening patterns after the American Cancer Society's recommendation to initiate screening at age 45 years. Cancer. 2020;126(6):1351–1353. doi: 10.1002/cncr.32662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ladabaum U, Mannalithara A, Meester RGS, Gupta S, Schoen RE. Cost-effectiveness and National Effects of initiating colorectal Cancer screening for average-risk persons at age 45 years instead of 50 years. Gastroenterology. 2019;157(1):137–148. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.03.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.O'Sullivan DE, Sutherland RL, Town S, Chow K, Fan J, Forbes N, Heitman SJ, Hilsden RJ, Brenner DR. Risk factors for early-onset colorectal Cancer: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;S1542-3565(21):00087–00082. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2021.01.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Breau G, Ellis U. Risk factors associated with young-onset colorectal adenomas and Cancer. A systematic review and Meta-analysis of observational research. Cancer Control. 2020;27(1):1073274820976670. doi: 10.1177/1073274820976670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rainey L, van der Waal D, Wengstrom Y, Jervaeus A, Broeders MJM. Women's perceptions of the adoption of personalised risk-based breast cancer screening and primary prevention: a systematic review. Acta Oncol. 2018;57(10):1275–1283. doi: 10.1080/0284186X.2018.1481291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bramer WM. Reference checking for systematic reviews using endnote. J Med Libr Assoc. 2018;106(4):542–546. doi: 10.5195/jmla.2018.489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rothman K, Keller A. The effect of joint exposure to alcohol and tobacco on risk of cancer of the mouth and pharynx. J Chronic Dis. 1972;25(12):711–716. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(72)90006-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang B, Shen T, Mao L, Xie L, Fang QL, Wang XP. Establishment of a risk prediction model for mild cognitive impairment among elderly Chinese. J Nutr Health Aging. 2020;24(3):255–261. doi: 10.1007/s12603-020-1335-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Viera AJ. Odds ratios and risk ratios: what's the difference and why does it matter? South Med J. 2008;101(7):730–734. doi: 10.1097/SMJ.0b013e31817a7ee4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang J, Yu KF. What's the relative risk? A method of correcting the odds ratio in cohort studies of common outcomes. JAMA. 1998;280(19):1690–1691. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.19.1690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schumacher AJ, Chen Q, Attaluri V, McLemore EC, Chao CR. Metabolic risk factors associated with early onset colorectal adenocarcinoma: a case-control study at Kaiser Permanente Southern California. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2021;30(10):1792–1798. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-20-1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chang VC, Cotterchio M, De P, Tinmouth J. Risk factors for early-onset colorectal cancer: a population-based case-control study in Ontario, Canada. Cancer Causes Control. 2021;32(10):1063–1083. doi: 10.1007/s10552-021-01456-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Low EE, Demb J, Liu L, Earles A, Bustamante R, Williams CD, Provenzale D, Kaltenbach T, Gawron AJ, Martinez ME, et al. Risk factors for early-onset colorectal Cancer. Gastroenterology. 2020;159(2):492–501. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gausman V, Dornblaser D, Anand S, Hayes RB, O'Connell K, Du M, Liang PS. Risk factors associated with early-onset colorectal Cancer. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;18(12):2752–2759. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2019.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen H, Zheng X, Zong X, Li Z, Li N, Hur J, Fritz CD, Chapman W, Jr, Nickel KB, Tipping A, et al. Metabolic syndrome, metabolic comorbid conditions and risk of early-onset colorectal cancer. Gut. 2021;70(6):1147–1154. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2020-321661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Syed AR, Thakkar P, Horne ZD, Abdul-Baki H, Kochhar G, Farah K, Thakkar S. Old vs new: risk factors predicting early onset colorectal cancer. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2019;11(11):1011–1020. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v11.i11.1011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Peters RK, Garabrant DH, Yu MC, Mack TM. A case-control study of occupational and dietary factors in colorectal cancer in young men by subsite. Cancer Res. 1989;49(19):5459–5468. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hofseth LJ, Hebert JR, Chanda A, Chen H, Love BL, Pena MM, Murphy EA, Sajish M, Sheth A, Buckhaults PJ, et al. Early-onset colorectal cancer: initial clues and current views. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;17(6):352–364. doi: 10.1038/s41575-019-0253-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Akimoto N, Ugai T, Zhong R, Hamada T, Fujiyoshi K, Giannakis M, Wu K, Cao Y, Ng K, Ogino S. Rising incidence of early-onset colorectal cancer - a call to action. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2021;18(4):230–243. doi: 10.1038/s41571-020-00445-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Silla IO, Rueda D, Rodriguez Y, Garcia JL, de la Cruz VF, Perea J. Early-onset colorectal cancer: a separate subset of colorectal cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(46):17288–17296. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i46.17288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kirzin S, Marisa L, Guimbaud R, De Reynies A, Legrain M, Laurent-Puig P, Cordelier P, Pradere B, Bonnet D, Meggetto F, et al. Sporadic early-onset colorectal Cancer is a specific sub-type of Cancer: a morphological, molecular and genetics study. PLoS One. 2014;9(8):e103159. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0103159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bailey CE, Hu CY, You YN, Bednarski BK, Rodriguez-Bigas MA, Skibber JM, Cantor SB, Chang GJ. Increasing disparities in the age-related incidences of colon and rectal cancers in the United States, 1975-2010. JAMA Surg. 2015;150(1):17–22. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2014.1756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.O’Connell JB, Maggard MA, Liu JH, Etzioni DA, Livingston EH, Ko CY. Do young colon cancer patients have worse outcomes? World J Surg. 2004;28(6):558–562. doi: 10.1007/s00268-004-7306-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tan KK, Lopez V, Wong ML, Koh GC. Uncovering the barriers to undergoing screening among first degree relatives of colorectal cancer patients: a review of qualitative literature. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2018;9(3):579–588. doi: 10.21037/jgo.2018.03.02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tan KK, Lim TZ, Chan DKH, Chew E, Chow WM, Luo N, Wong ML, Koh GC. Getting the first degree relatives to screen for colorectal cancer is harder than it seems-patients' and their first degree relatives' perspectives. Int J Color Dis. 2017;32(7):1065–1068. doi: 10.1007/s00384-017-2818-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kaminski MF, Polkowski M, Kraszewska E, Rupinski M, Butruk E, Regula J. A score to estimate the likelihood of detecting advanced colorectal neoplasia at colonoscopy. Gut. 2014;63(7):1112–1119. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2013-304965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rank KM, Shaukat A. Stool based testing for colorectal Cancer: an overview of available evidence. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2017;19(8):39. doi: 10.1007/s11894-017-0579-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sun M, Liu J, Hu H, Guo P, Shan Z, Yang H, Wang J, Xiao W, Zhou X. A novel panel of stool-based DNA biomarkers for early screening of colorectal neoplasms in a Chinese population. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2019;145(10):2423–2432. doi: 10.1007/s00432-019-02992-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Church TR, Wandell M, Lofton-Day C, Mongin SJ, Burger M, Payne SR, Castanos-Velez E, Blumenstein BA, Rosch T, Osborn N, et al. Prospective evaluation of methylated SEPT9 in plasma for detection of asymptomatic colorectal cancer. Gut. 2014;63(2):317–325. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-304149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Murphy CC. Colorectal Cancer in the young: does screening make sense? Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2019;21(7):28. doi: 10.1007/s11894-019-0695-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mehta SS, Arroyave WD, Lunn RM, Park YM, Boyd WA, Sandler DP. A prospective analysis of red and processed meat consumption and risk of colorectal Cancer in women. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2020;29(1):141–150. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-19-0459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zahnd WE, Gomez SL, Steck SE, Brown MJ, Ganai S, Zhang J, Arp Adams S, Berger FG, Eberth JM. Rural-urban and racial/ethnic trends and disparities in early-onset and average-onset colorectal cancer. Cancer. 2021;127(2):239–248. doi: 10.1002/cncr.33256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Muller C, Ihionkhan E, Stoffel EM, Kupfer SS. Disparities in Early-Onset Colorectal Cancer. Cells. 2021;10(5):1018. doi: 10.3390/cells10051018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Siegel RL, Medhanie GA, Fedewa SA, Jemal A. State variation in early-onset colorectal Cancer in the United States, 1995-2015. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2019;111(10):1104–1106. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djz098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Marley AR, Nan H. Epidemiology of colorectal cancer. Int J Mol Epidemiol Genet. 2016;7(3):105–114. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhang L, Cao F, Zhang G, Shi L, Chen S, Zhang Z, Zhi W, Ma T. Trends in and predictions of colorectal Cancer incidence and mortality in China from 1990 to 2025. Front Oncol. 2019;9(98):98. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2019.00098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Patel P, De P. Trends in colorectal cancer incidence and related lifestyle risk factors in 15-49-year-olds in Canada, 1969-2010. Cancer Epidemiol. 2016;42:90–100. doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2016.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang L, Gao P, Zhang M, Huang Z, Zhang D, Deng Q, Li Y, Zhao Z, Qin X, Jin D, et al. Prevalence and ethnic pattern of diabetes and Prediabetes in China in 2013. JAMA. 2017;317(24):2515–2523. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.7596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ordonez-Mena JM, Walter V, Schottker B, Jenab M, O'Doherty MG, Kee F, Bueno-de-Mesquita B, Peeters PHM, Stricker BH, Ruiter R, et al. Impact of prediagnostic smoking and smoking cessation on colorectal cancer prognosis: a meta-analysis of individual patient data from cohorts within the CHANCES consortium. Ann Oncol. 2018;29(2):472–483. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdx761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cai S, Li Y, Ding Y, Chen K, Jin M. Alcohol drinking and the risk of colorectal cancer death: a meta-analysis. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2014;23(6):532–539. doi: 10.1097/CEJ.0000000000000076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Triantafillidis JK, Nasioulas G, Kosmidis PA. Colorectal cancer and inflammatory bowel disease: epidemiology, risk factors, mechanisms of carcinogenesis and prevention strategies. Anticancer Res. 2009;29(7):2727–2737. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zheng X, Hur J, Nguyen LH, Liu J, Song M, Wu K, Smith-Warner SA, Ogino S, Willett WC, Chan AT, et al. Comprehensive assessment of diet quality and risk of precursors of early-onset colorectal Cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2021;113(5):543–552. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djaa164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1. The individual risk scores of 10,000 simulated subjects.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].