Abstract

As people around the world work to stop the COVID-19 pandemic, mutated COVID-19 (Delta strain) that are more contagious are emerging in many places. How to develop effective and reasonable plans to prevent the spread of mutated COVID-19 is an important issue. In order to simulate the transmission of mutated COVID-19 (Delta strain) in China with a certain proportion of vaccination, we selected the epidemic situation in Jiangsu Province as a case study. To solve this problem, we develop a novel epidemic model with a vaccinated population. The basic properties of the model is analyzed, and the expression of the basic reproduction number is obtained. We collect data on the Delta strain epidemic in Jiangsu Province, China from July 20, to August 5, 2021. The weighted nonlinear least square estimation method is used to fit the daily asymptomatic infected people, common infected people and severe infected people. The estimated parameter values are obtained, the approximate values of the basic reproduction number are calculated . Through the global sensitivity analysis, we identify some parameters that have a greater impact on the prevalence of the disease. Finally, according to the evaluation results of parameter influence, we consider three control measures (vaccination, isolation and nucleic acid testing) to control the spread of the disease. The results of the study found that the optimal control measure is to dynamically adjust the three control measures to achieve the lowest number of infections at the lowest cost. The research in this paper can not only enrich theoretical research on the transmission of COVID-19, but also provide reliable control suggestions for countries and regions experiencing mutated COVID-19 epidemics.

Keywords: COVID-19 Model, Delta strain, Imperfect vaccination, Weighted nonlinear least square estimation, Optimal control

MSC: 34D23, 49J15

1. Introduction

The outbreak of COVID-19 in 2020 has yet to be fundamentally contained. It puts a long pause button on the lives of people around the globe. It has seriously affected people’s health, life and work [1]. To help people out, experts in many countries are working on COVID-19 vaccines. In early 2021, the global epidemic improved thanks to the development of vaccines and the control of vaccination rates by many countries [2].

New strains of COVID-19 with high transmission rates are circulating around the world, such as the Alpha strain in the UK, the Beta strain in South Africa and the Delta strain in India [3]. At a recent WHO regular COVID-19 briefing, Soumya Swaminathan, WHO Chief Scientist, said that this novel Coronavirus variant is on its way to becoming the main circulating novel Coronavirus variant globally due to the significantly increased transmissibility of the Delta variant. It is characterized by rapid transmission, strong infectivity and atypical initial symptoms. The effectiveness of existing COVID-19 vaccines against Delta strain has been reduced, and some vaccinated people can still become infected with Delta strain, but must not become severely infected [4]. When The Chinese mainland was enjoying the victory over the epidemic, the imported Delta strain began a new round of transmission in the Chinese mainland [5].

On July 20, 2021, seven positive samples were found during routine nucleic acid tests at Lukou Airport in Nanjing, all of them from airport cleaning staff [6]. On July 21, four districts in Nanjing were upgraded to medium-risk areas. On July 22, and 23, 12 new cases were confirmed daily, and some areas of Nanjing were elevated to high-risk areas. Since then, six cities in Jiangsu province have confirmed cases of Delta strain.

Many scholars have studied the spread of COVID-19 in various places from different perspectives. One of the important ideas is to study the spread of COVID-19 through mathematical models. To that end, a number of mathematical models have been developed over the past two years to study local infections, estimate peaks in the number of people infected, and suggest ways to control the spread of the disease [7], [8], [9], [10], [11], [12], [13], [14], [15], [16], [28], [29], [30], [31], [32], [33], [34], [35], [36], [37], [38], [39], [40].

Sun et al. [7] established a SEIQR mathematical model to analyze the impact of the lockdown measures in Wuhan in 2020 on the spread of COVID-19. Neto et al. [8] built a SEHCR mathematical model, using a multi-objective genetic algorithm to analyze the local COVID-19 prevalence in Sao Paulo, Brazil, and suggested that the best intervention is to limit social distancing. Considering that communities and hospitals are different from other Spaces in the process of disease transmission, Zhu et al. [9] proposed a SEIR-HC mathematical model to analyze the dynamic properties of disease transmission in Wuhan. The analysis showed that the base reproduction number for COVID-19 was 7.9, much higher than for many other infectious diseases. Kwuimy et al. [10] developed a SEIR mathematical model, taking into account public behavior and government interventions, and used the genetic algorithms to simulate and analyze COVID-19 data in South Korea in 2020. Olaniyi et al. [11] proposed a COVID-19 model with a new incidence, performed parameter estimation and cost-effective analysis on the transmission of COVID-19 in Nigeria, and provided a most cost-effective control scheme.

Optimal control theory, a major branch of modern control theory, is a subject to study and solve the search for optimal solutions from all possible control schemes. Optimal control theory has been applied by many scholars to solve the problem of infectious disease control in recent years [17], [18], [19], [20]. Zhang et al. [17] considered a Huanglongbing model with comprehensive intervention means and applied optimal control theory to get the optimal control strategy. The results showed that the coupled control strategy of spraying insecticide and clearing HLB symptom tree was the most cost-effective strategy. Li and Guo [18] considered the influence of media on game addiction and established an online game addiction model with positive and negative media reports. Through the analysis of optimal control theory, the results showed that reasonable control of media coverage can effectively reduce the phenomenon of game addiction. Alzahrani et al. [19] developed a mathematical model of mutated Zika virus, estimated parameters using data from Colombia in 2016, and proposed a set of control measures to eliminate Zika virus from communities. Yıldız and Karaoǧlu [20] considered the situation of exogenous reinfection of tuberculosis to establish a new dynamic model with treatment at home and treatment at hospital. Through the analysis of optimal control, the control strategy with optimal conversion rate between treatment at home and treatment at hospital was obtained.

There are two important differences between the spread of COVID-19 in 2021 and 2020. The first is that a certain percentage of people in many countries will already be vaccinated in 2021. While these vaccines can’t completely protect people from infection, they can reduce the severity of infection to some extent when fighting COVID-19. The second is that there are many different types of mutations in COVID-19 that make them different in their infectivity and mortality. Much has been written about control measures for COVID-19 as it spreads around the world in 2020. However, noting these differences, there have been few studies on the spread of mutated COVID-19 in populations with a certain proportion of vaccinations.

Inspired by the above literatures, in order to simulate and control the spread of mutated COVID-19 (Delta strain) in a vaccinated population in China, a novel mathematical model with vaccinated populations was developed.

2. The model formulation

2.1. System description

We divided the total population into seven compartments.

: the group of susceptible people who are not vaccinated;

: the group that has been vaccinated and has developed antibodies;

: the group that has been vaccinated but whose antibodies decrease over time;

: the group of asymptomatic infected persons;

: the group of people infected with common symptoms;

: the group of people with severe symptoms;

: the confirmed asymptomatic cases;

: the confirmed common cases;

: the confirmed severe cases;

: the group of people who have been infected with COVID-19 and have recovered.

Thus, the total population is given by:

| (1) |

The population flow among those compartments is shown in Fig. 1 . A susceptible person can become infected with COVID-19 when they come into contact with an infected person in , and . The intensity of the infection is

A susceptible person who has not been vaccinated in may become asymptomatic infected person , ordinary infected person , or severe infected person . Since the vaccine can prevent the infected person from becoming severe infection with a 100% probability [4], the susceptible person vaccinated in may become asymptomatic infection or ordinary infection .

Fig. 1.

Transfer diagram of model.

Thus, the transfer diagram leads to the following system of ordinary differential equations:

| (2) |

where

is the birth rate;

is the natural mortality rate in all classes;

denotes the rate of vaccination;

denotes the rate of supplemental vaccination;

denotes the rate at which antibodies are gradually lost in the body;

is transmission rate of contact with asymptomatic infected persons;

is transmission rate of contact with common infected persons;

is transmission rate of contact with severe infected persons;

is the proportion of susceptible population to severe infected persons ;

is the proportion of susceptible population to common infected persons ;

is the proportion of the population with weakened antibodies to common infected persons ;

is the rate of treatment of asymptomatic infected persons after diagnosis;

is the rate of treatment of common infected persons after diagnosis;

is the rate of treatment of severe infected persons after diagnosis;

is the recovery rate of asymptomatic infected people;

is the recovery rate of common infected people;

is the recovery rate of severe infected people;

is the death rate due to COVID-19 infection;

For the convenience of expression, let’s make the following shorthand. , , , , , , , , .

2.2. Positivity and boundedness of solutions

Since the number of people in each compartment of model (2) is nonnegative and finite, we want to verify here that the solution of model (2) is non-negative and bounded for all .

System (2) can be put into the matrix form

| (3) |

where and is given by

Letting , the first equation of model (2) yields

Since system (2) has non-negative initial values, we use the integrating factor method and the solution is as follows.

Similarly, we can get the rest of the variables to be positive. Because of , we get

Thus,

is a positive invariant set of system (2).

2.3. The basic reproduction number

By solving system (2), we can get a disease-free equilibrium as follows.

| (4) |

In the following, the basic reproduction number of system (2) will be obtained by the next generation matrix method [21]. Let , then system (2) can be written as

| (5) |

where

The Jacobian matrices of and at the disease-free equilibrium are

where

The basic reproduction number [21], denoted by , is given by

where represents the spectral radius of a matrix . Since is greater than 0, the basic reproduction number is always positive.

2.4. Existence of endemic equilibrium

The Endemic Equilibrium of system (2) is determined by equations:

By solving the above equations, we get the following conclusion.

| (6) |

where

| (7) |

Equations in (6) are substituted into Eq. (7), and we get the following relationship.

| (8) |

where

| (9) |

Clearly, and is negative when . Thus, the following theorem is established.

Theorem 1

For the model (2), there exists an Disease-Free Equilibrium=,,, 0,0,0,0,0,0,0). And the model (2) has:

- (i)

If, then model (2) has a unique Endemic Equilibrium if,

- (ii)

If,or, then model (2) has a unique Endemic Equilibrium,

- (iii)

If,andthen model (2) has two Endemic Equilibrium,

- (iv)

Otherwise no Endemic Equilibrium exists.

3. Stability of disease-free equilibrium

In this section, we will discuss the local and global stability of Disease-Free Equilibrium. For the local stability, we propose the following result.

Theorem 2

The Disease-Free Equilibriumis locally asymptotically stable ifand unstable otherwise.

Proof

The Jacobian matrix at the Disease-Free Equilibrium is

(10) where

We can easily obtain the characteristic roots of the matrix (10): , , , , , and are the characteristic roots of , , , and are the characteristic roots of , where

The characteristic equation of is

Because and are positive, the characteristic roots of have negative real parts. The characteristic equation of is

where

And after some simplifying, we can get

When , we can conclude that the following inequalities are true.

Thus, we obtain that , and . By using the Routh-Hurtwiz criteria, the Disease-Free Equilibrium of the system (2) is Locally Asymptotically Stable (LAS). □

The Global Asymptotic Stability of DFE of the model (2) is proved in the following theorem.

Theorem 3

The Disease-Free Equilibriumof model (2) is Globally Asymptotically Stable ifand unstable otherwise.

Proof

A continuous differentiable and positive definite Lyapunov function constructed for the COVID-19 model (2) is as follows.

where, are nonnegative constants to be determined.

The time derivative of along the solution path of system (2) is given by

Assuming , we can obtain the expressions of and .

So

Thus, it is obvious that when . By using the LaSalle’s invariant principle, is Globally Asymptotically Stable in the region . □

4. Optimal control

In this section, we will use the Pontriagin maximum principle in optimal control theory to find the optimal control strategy during the transmission of COVID-19. Our goal is to minimize the cumulative number of infections and the cost associated with the spread of the disease. We consider the following key control measures: increasing vaccination rates, increasing the intensity of daily isolation and nucleic acid testing for all people in the city. The specific control means are described below.

-

(1)

represents vaccination measure aimed at preventing and controlling the spread of COVID-19 by increasing the number of people vaccinated. The control measures are mainly implemented through two programmes: one is to increase vaccination in unvaccinated susceptible group ; The second is to supplement the COVID-19 antibody to , a population with weakened antibodies. represents the rate of vaccination in and .

-

(2)

represents the measure to isolate the virus, which are mainly achieved through isolation of infected persons, disinfection of the environment and increasing the daily wear of masks when going out.

-

(3)

stands for nucleic acid test for all people in the city, with the aim of screening out all asymptomatic infected person , common infected person and severe infected person , and then treating them separately. represents the probability of successful screening of a nucleic acid test.

We consider the above three control variables into model (2) to determine the optimal control strategy and get the following nonlinear systems.

| (11) |

The effect of control is determined by the following objective function,

| (12) |

where are the weight coefficients of the infected people. The constants are the weight coefficients of the control variables . Our main concern is to find optimal controls such that

| (13) |

Here, , for all , . The control set is shown as

| (14) |

On the basis of the Pontryagin’s maximum principle [22], we set up the Hamiltonian function as follows

where are the adjoint variables.

Theorem 4

Given optimal control pairsand solutions,,,,,,,,,of the state system (18), there exist adjoint variables, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10), satisfying the following adjoint system

The terminal condition of adjoint equations is given by

(15) And the optimal controls are given by

Proof

According to the Pontryagin’s Maximum Principle [22], we differentiate the Hamiltonian operator . The adjoint system can be written as

and satisfy the condition

By solving the above equations, the proof is completed. □

5. Numerical simulation

5.1. Data colloction

We obtained relevant case data from the official website of Health Commission of Jiangsu Province, China [6]. The data, including new cases, cumulative cases, asymptomatic cases, common cases and severe cases, are shown in Table 1 .

Table 1.

Statistics Population in NHC of Jiangsu Province, China.

| Date | New cases | Cumulative cases | Confirmed asymptomatic cases | Confirmed common cases | Confirmed severe cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2021/07/20 | 7 | 7 | 4 | 3 | 0 |

| 2021/07/21 | 4 | 11 | 6 | 5 | 0 |

| 2021/07/22 | 12 | 23 | 12 | 10 | 1 |

| 2021/07/23 | 12 | 35 | 19 | 15 | 1 |

| 2021/07/24 | 2 | 37 | 20 | 16 | 1 |

| 2021/07/25 | 39 | 76 | 41 | 33 | 2 |

| 2021/07/26 | 31 | 110 | 66 | 39 | 2 |

| 2021/07/27 | 48 | 158 | 81 | 70 | 4 |

| 2021/07/28 | 20 | 178 | 78 | 90 | 7 |

| 2021/07/29 | 18 | 196 | 86 | 99 | 8 |

| 2021/07/30 | 19 | 215 | 93 | 110 | 9 |

| 2021/07/31 | 30 | 245 | 97 | 137 | 8 |

| 2021/08/01 | 40 | 288 | 97 | 177 | 8 |

| 2021/08/02 | 45 | 335 | 116 | 203 | 8 |

| 2021/08/03 | 35 | 373 | 122 | 234 | 6 |

| 2021/08/04 | 40 | 413 | 131 | 253 | 12 |

| 2021/08/05 | 61 | 474 | 135 | 299 | 16 |

The cumulative cases are shown in Fig. 2 . Figure 2 also reflects the spread of mutated COVID-19 (Delta strain) in populations with a certain proportion of vaccination. As can be seen from Fig. 2, the growth rate of the curve is slower than that of [40]. This suggests that the transmission rate of Delta virus in a population in which a fraction of the population has been vaccinated has slowed. Although the mutated strain is more infectious, the intensity of transmission can still be greatly reduced by the vaccine. Vaccination plays a role in controlling the spread of COVID-19 among people.

Fig. 2.

The cumulative cases per day in Jiangsu Province, China from July 20, 2021 to August 8, 2021.

5.2. Parameter estimation

This section uses COVID-19 model (2) to simulate the data obtained above. Before parameter estimation, some parameter values can be obtained from some existing literatures. For example, according to the data of the seventh national population census released by the National Bureau of Statistics of China in 2020, the average life expectancy of Chinese people is 77 years old [23], so we assume the natural mortality rate per day. It also shows that the total population of Jiangsu province in 2020 is 84,748,016. We assume that is the limit cumulative number without infection, so per day. At the same time, we are pleased to note that there were no deaths due to COVID-19 during this period due to improved health care, adequate medical resources and vaccine protection, so we set the death rate .

In order to make full use of the collected data, we choose nonlinear weighted least square estimation method for parameter estimation [24]. The main steps of this statistical method are described as follows. The sum of the squares errors (SSE), is expressed mathematically as:

where are the reported data, are the solution of the model (2) at time . , and are the weight coefficients of each reported data sequence, and their values are the reciprocal of the variances of each sequence. The goal is to minimize the following objective function

| (16) |

We use the fminsearch function in MATLAB to fit the real data, and the fitting results are shown in Fig. 3 . It can be seen from the results in Fig. 3 that the fitting results are very close to the real data and the obtained results are reliable. All of the resulting parameter values are shown in Table 2 . Combined with the expression of the basic reproduction number in the previous theory, we can get the approximate value of the basic reproduction number is .

Fig. 3.

Fitting result to the reported data using model (2).

Table 2.

Estimated parameters for model (2).

| Parameters | Descriptions | Values | Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| Natural death rate | Estimated | ||

| Recruitment rate | Estimated | ||

| Rate of vaccination | 0.016699 | Fitted | |

| Rate of supplemental vaccination | 0.006981 | Fitted | |

| The percentage of vaccine antibodies that decline | 0.010396 | Fitted | |

| Contact rate of asymptomatic infected people | 0.436923 | Fitted | |

| Contact rate of common infected people | 0.768044 | Fitted | |

| Contact rate of severe infected people | 0.000131 | Fitted | |

| Transmission rate from to | 0.076371 | Fitted | |

| Transmission rate from to | 0.008571 | Fitted | |

| Transmission rate from to | 0.007979 | Fitted | |

| Rate of being diagnosed in | 0.196831 | Fitted | |

| Rate of being diagnosed in | 0.059082 | Fitted | |

| Rate of being diagnosed in | 0.006502 | Fitted | |

| Recovery rate of asymptomatic infected people | 0.715480 | Fitted | |

| Recovery rate of common infected people | 0.000207 | Fitted | |

| Recovery rate of severe infected people | 0.214278 | Fitted |

By the biological significance of the basic reproduction number, we know that when , the disease gradually spreads out in the population. The main means of controlling the spread of disease through drug intervention is vaccination. We increased the values of vaccination proportion and supplemental vaccine antibody proportion separately to observe their effects on the number of infections. The results are shown in Fig. 4 .

Fig. 4.

Increasing the rate of vaccination and supplemental vaccination .

As can be seen from the comparison results in Fig. 4, when we increase and , the number of people in all three infected compartments decreases to varying degrees. This result is what we would like to see. By comparing the subplots in Fig. 4, we can see that increasing has better results than increasing . But that’s just a graphical observation. In order to quantify and evaluate the influence of each parameter on the basic reproduction number , we will further perform uncertainty and sensitivity analysis on the model.

5.3. Uncertainty analysis and global sensitivity analysis

In this section, we discuss the uncertainty and sensitivity analysis of the important threshold parameters, namely, , to determine those model parameters that have the greatest impact on disease dynamics. This analysis quantifies the uncertainty in any complex model in math. In particular, sensitivity analysis is used to study the contribution of initial parameters and conditions to model results. In order to achieve this goal, we use a very efficient statistical techniques that a combination of latin hypercube sampling (LHS) and partial rank correlation coefficient (PRCC) is used. In the method, we obtain the values of PRCC for each parameter, which can be used to help estimate the level of uncertainty in mathematical models. For a more detailed introduction of this method, please refer to [25].

In order to generate the LHS matrices, we make all parameters subject to uniform distribution. We set up a total of 1000 simulations. After Latin hypercube sampling, we get the LHS matrix of the corresponding basic reproduction number. We removed some sparse outliers less than 0 or greater than 5. The frequency of is shown in Fig. 5 . As shown in Fig. 5, we get that the mean, 5th and 95th percentiles being 1.1506, 0.1548 and 3.1995 of the distribution for . In the previous section, we estimated to be 1.378, which is close to the mean. The estimate of is indicated by a red dotted line in Fig. 5. We notice that the distribution of is very wide, so its uncertainty is very high. And most of the values of are smaller than the estimated values of . Therefore, we want to further analyze which parameters have a greater influence on and consider the control means in reality through the analysis results. PRCC values of all parameters in are shown in Fig. 6 in the form of bar charts, and the corresponding P-values are shown in Table 3 .

Fig. 5.

Uncertainty analysis of .

Fig. 6.

Global sensitivity analysis of model parameters and PRCC results for .

Table 3.

Partial rank correlation coefficient for .

| Parameters | PRCC | P-value | Parameters | PRCC | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| -0.006183 | 0.846100 | 0.355045 | 0.000000 | ||

| -0.422072 | 0.000000 | -0.011950 | 0.707551 | ||

| -0.193928 | 0.000000 | -0.014944 | 0.638945 | ||

| 0.213412 | 0.000000 | -0.368768 | 0.000000 | ||

| 0.276643 | 0.000000 | -0.340624 | 0.000000 | ||

| 0.229595 | 0.000000 | -0.313606 | 0.000000 | ||

| 0.334942 | 0.000000 |

The PRCC values of all parameters in , the significance results of the parameters are given in Table 3. When , there is a significant correlation between the input parameters and the output result . As can be seen from the results in Fig. 6, , , , and have higher positive PRCC values. This suggests that we can reduce by decreasing the value of these parameters. On the other hand, , , , and have large negative PRCC values. This indicates that if we increase the values of these parameters, it will help to reduce the basic reproduction number . is the rate at which antibodies disappear in the body, and is the percentage of susceptible people who become asymptomatic after becoming infected. These are factors that are not easy to control. The remaining important influence parameters will be divided into three groups for discussion.

-

(1)

and : represent the rate of vaccination and the rate of supplementary vaccination respectively, which have a very strong influence on . Therefore, increasing vaccination to establish an immune barrier as quickly as possible can effectively reduce . So we are considering increasing vaccination coverage as an important measure to control the spread of COVID-19.

-

(2)

, and : represent the contact rates of the three infected chambers respectively. We can see from Fig. 6 that their PRCC values are positive, indicating that they are positively correlated with . We can consider reducing the exposure rate to reduce the value of , so as to achieve the effect of suppressing the spread of COVID-19. In reality, the answer is that all people need to maintain social distancing and reduce the chance of intersecting. Therefore, we consider isolation as the second important measure to control COVID-19.

-

(3)

, and : represent the rates at which people from the three infected compartments were transferred to treatment chambers after being confirmed by nucleic acid tests. As shown in Fig. 6, they all have large negative PRCC values, which means that we can reduce by increasing their values to achieve the effect of controlling the spread of COVID-19. In practice, the response would be to test everyone in the area for nucleic acid, so as to get as many infected people as possible to treatment and reduce the likelihood of further transmission. Therefore, we will consider nucleic acid testing for all people as a third important means of control.

5.4. Optimal control

In this subsection, we will perform numerical simulations on the model without control (2) and model with control (9) to illustrate the importance of control means. An efficient forward-backward sweep method is used to solve the system with control. For detailed introduction and application of this method, please refer to references [17], [18], [19], [20], [21], [22], [23]. The values of all parameters are shown in Table 2. The time span of the simulation is 30 days. After investigation, it is known that the effective rate of Chinese vaccination to produce antibodies is 65% [4], [26]. The usual incubation period for COVID-19 is 14 days, with an average of 7 days [27]. So we choose , . After some experimental calculations, these weight parameters are evaluated as:, . In the objective world, the control effect will be affected by a variety of factors and it is very difficult to achieve the ideal 100% state, so we set the maximum value of the control variable as 0.8. In order to explore the effect of each control means, we set up the following control scheme.

-

•Scenario 1: Single control strategies

- Strategy A: Vaccination only ().

- Strategy B: Isolation only ().

- Strategy C: Detection only ().

-

•Scenario 2: Double control strategies

- Strategy D: Vaccination () + Isolation ().

- Strategy E: Vaccination () + Detection ().

- Strategy F: Isolation () + Detection ().

-

•Scenario 3: Triple control strategies

- Strategy G: Vaccination () + Isolation () + Detection ().

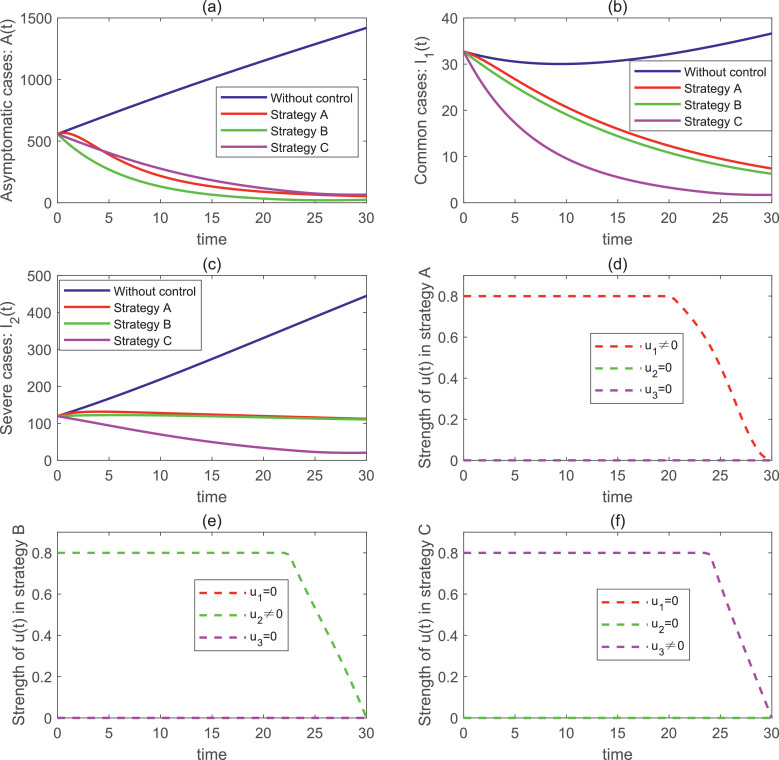

Fig. 7 (a–c) show the changes in the number of asymptomatic infected people , common infected people and severe infected people in scenario 1. Fig. 7(d–f) reflect the change rule of the control variable in scenario 1. As can be seen from the Fig. 7(d), the control strength of should be maintained at the maximum strength of 0.8 at the beginning for 20 days, and then gradually decrease to 0. In strategy B, the control strength of should be kept at the maximum strength of 0.8 from the beginning, and gradually decreased to 0 until the 22nd day. In strategy C, the control intensity of needs to maintain a maximum intensity of 0.8 for the first 24 days and then gradually decrease to 0.

Fig. 7.

The dynamical trajectories of , , and in scenario 1.

From Fig. 7(a–c), we can see that the number of infected people under strategy A, strategy B and strategy C are significantly lower than that without control. Moreover, we also found that strategy B had the lowest number of asymptomatic infections, while strategy C had the lowest number of common and severe cases.

These results show that all three control measures have some inhibitory effect on the spread of mutated COVID-19. The best single control measure is strategy C.

Figure 8 (a–c) show the changes in the number of asymptomatic infected people , common infected people and severe infected people in scenario 2. Figure 8 (d–f) reflect the change rule of the control variable in scenario 2. As can be seen from the Fig. 8(d), the control strength of and should be maintained at the maximum strength of 0.8 at the beginning for 2 days and 18 days, then gradually decrease to 0. In strategy E, the control strength of and should be kept at the maximum strength of 0.8 from the beginning, and gradually decreased to 0 until day 5 and day 12, respectively. In strategy F, the control intensity of and needs to maintain a maximum intensity of 0.8 for the first 12 days and then gradually decrease to 0.

Fig. 8.

The dynamical trajectories of , , and in scenario 2.

In Fig. 8 (a), we can see that strategy F will have the lowest number of asymptomatic infections. In Fig. 8 (b-c), we can see that the number of cases in both strategy E and strategy F is very small. Therefore, we believe that in scenario 2 of double control measures, strategy F is the most effective double control strategy.

Figure 9 (a–c) show the changes in the number of asymptomatic infected people, common infected people and severe infected people under without control and strategy G. Figure 9(d) shows the changes in the strength of the two control variables under strategy G. The control variables , and need to be maintained at the maximum strength of 0.8 at the beginning, which lasts until the 2nd, 9th and 11th day respectively, and then gradually decreases to 0.

Fig. 9.

The dynamical trajectories of , , and in scenario 3.

As can be seen from Fig. 9(a–c), the number of people in each infected compartment under strategy G decreased significantly compared with that without control. Comparing Fig. 7, Fig. 8 and 9, we find that strategy G seems to have the least number of infections, but it is not so clear from the image alone. To compare all control strategies, we need to further calculate the total infectious individuals and the total averted cases , where () denote the infected people of without control, () denote the infected people of a control strategy. The results of all calculations are shown in Table 4 .

Table 4.

Comparison of different strategies.

| Strategy | Total infectious individuals(TI) | Total averted infectious individuals (TA) | Infection averted ratio(IAR) | Objective function (J) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Without control | 39377.1470 | - | - | 39377.1470 |

| Strategy A | 10259.6806 | 29117.4664 | 73.9451% | 11023.3541 |

| Strategy B | 7904.3330 | 31472.8140 | 79.9266% | 8703.9809 |

| Strategy C | 8720.8212 | 30656.3258 | 77.8531% | 9548.0656 |

| Strategy D | 7092.5969 | 32284.5501 | 81.9880% | 7983.1850 |

| Strategy E | 4344.2031 | 35032.9439 | 88.9677% | 5186.5590 |

| Strategy F | 3559.6179 | 35817.5291 | 90.9602% | 4588.0139 |

| Strategy G | 3329.9874 | 36047.1596 | 91.5434% | 4298.7053 |

As you can see from the IAR data of Table 4, strategy G can prevent more people from becoming infected. This also indicates that strategy G is the optimal control strategy we are looking for. We should implement , and at the same time according to the control plan shown in Fig. 9(d), so as to minimize the number of infections and control the spread of the disease as soon as possible.

In Fig. 9(d), it is shown that the three control measures should change dynamically. The first control, which increased the rate of vaccination, was initially at maximum intensity, rapidly decreasing to a level of 0.2 between day 2 and day 7, and slowly decreasing to 0 over the following 23 days. Because of the level of vaccine production and the number of health workers, it is difficult to rely on vaccination to make a large number of people produce antibodies in a short period of time and stop the spread of COVID-19. Therefore, maintaining maximum vaccination levels is not very effective in preventing the spread of COVID-19. Increased vaccination controls should be viewed as a complementary measure in the event of a sudden outbreak of COVID-19 transmission.

The second control measure (isolation) should be maintained at the maximum control level at the beginning and gradually reduced to zero by the 9th day. This is mainly because, in the case of a sudden outbreak of COVID-19, quarantine measures are effective in stopping the spread of the disease by cutting off the route of transmission in the real world. At the same time, it is worth noting that the effectiveness of this measure depends not only on the control of government departments, but also on the active cooperation of people.

The third control measure (detection), at the beginning, also needs to be maintained at the maximum level of control so that infected people can be quickly transferred to hospitals and isolated for treatment as soon as possible. The control intensity of the test continued until day 11 and then gradually decreased to 0. This measure effectively reduces the source of COVID-19 transmission in the population and plays an important role in the rapid control of COVID-19 transmission from the source.

6. Conclusion

Since the beginning of 2020, COVID-19 has spread rapidly across the globe, posing important challenges to people’s health. The spread of the disease has been curbed to some extent by the advent of the COVID-19 vaccine. But the mutated COVID-19 (Delta strain) is much more contagious, once again creating a pandemic. To study the spread of Delta strain in populations, we developed a new mathematical model of COVID-19 transmission with imperfect vaccination.

The first part of this paper was some theoretical analysis of the model. Firstly, we studied the positivity and boundedness of the solution of the model, and obtained the expression of the basic reproduction number with important biological significance by using the method of the next generation matrix. Then a new status system with control variables was obtained by embedding three controls (vaccination , isolation and detection ). Using the Pontryagin maximum principle, the expression of optimal control was obtained.

The second part of this paper was numerical simulation. First of all, we collected the data of daily infection cases from July 20, to August 5, 2021 on the official website of Jiangsu Provincial Health Commission of China. In order to make full use of these high quality data, the nonlinear weighted least squares estimation method was applied to estimate parameters. The approximate value of the basic reproduction number . This result showed a significant decrease in value compared with previous literature, suggesting that vaccination also had a certain inhibitory effect on the transmission of the Delta strain. Through the sensitivity analysis, the effect of each parameter on the system was shown. Finally, we simulated the results of each strategy by using the forward and backward sweep method with the fourth order Runge-kutta, and obtained the optimal control strategy by analyzing the data of infection averted ratio of each strategy.

Based on the research work done in this paper, some novel contents different from the existing papers are summarized as follows:

-

•

A novel mathematical model of mutated COVID-19 has been developed. In the model, we took into account not only the important differences between vaccinated, antibody weakened and unvaccinated populations, but also the fact that the inactivated vaccine has some effect on the Delta strain, preventing it from becoming severely ill but still potentially infected.

-

•

In parameter estimation, unlike many scholars who only fit the total number of confirmed cases, we used weighted nonlinear least squares estimation method to fit the data of officially reported asymptomatic, mild and severe cases. More detailed fitting results can provide more accurate analysis results and is the basis for effective follow-up work.

-

•

In the control simulation, different from the control measures (isolation and detection) in the previous literature, we consider the control measures to increase the speed of vaccination. Our study found that with the inclusion of vaccination measures, dynamic adjustment of the strength of the three control measures could further reduce the number of infected individuals.

Mutated COVID-19 (the Delta strain), due to its strong infectivity, can produce mass transmission in populations with imperfect vaccination. How to formulate effective control measures has become an important problem. The results of this study suggest how three different control strategies should be dynamically adjusted to minimize the number of infections and cost as much as possible. These findings clearly demonstrate the feasibility of developing an optimal vaccine schedule. The results can provide an important reference for many countries and regions that are experiencing the spread of delta virus to develop vaccine programs.

The fractional derivative can be regarded as the globalization of the integral derivative, which can show more properties that the integral derivative does not have. Many scholars have applied fractional derivative differential equations to study the spread of COVID-19, and many important research results have been obtained [31], [32], [33], [34], [35], [36]. If we consider fractional COVID-19 model for parameter estimation, different results with higher fitting degree may be obtained, and the measures taken may be changed. This is an interesting question, and we leave it for later.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Tingting Li: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Formal analysis, Resources, Data curation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Youming Guo: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Supervision.

Declaration of Competing Interest

There are no conflicts of interest by the authors.

Acknowledgment

The authors are grateful to the editor and the reviewers for their valuable comments and suggestions.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Weekly epidemiological update on COVID-19. 2021a. May 20, https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/weekly-epidemiological-update-on-covid-19-20-May-2021. Accessed: 2021-05-20.

- 2.Bollyky T.J. U.S. COVID-19 vaccination challenges go beyond supply. Ann Intern Med. 2021;174(4):558–559. doi: 10.7326/M20-8280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization. Tracking SARS-CoV-2 variants. 2021b. May 31, https://www.who.int/en/activities/tracking-SARS-CoV-2-variants. Accessed: 2021-05-31.

- 4.Li X.N., Huang Y., Wang W., Jing Q.L., Zhang C.H., Qin P.Z., et al. Effectiveness of inactivated SARS-CoV-2 vaccines against the Delta variant infection in Guangzhou: a test-negative case-control real-world study. Emerg Microbes Infec. 2021;10(1):1751–1759. doi: 10.1080/22221751.2021.1969291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wu B., Zhang H., Wang Y.C., Tang A., Li K.F., Li P., et al. Sequencing on an imported case in China of COVID-19 Delta variant emerging from India in a cargo ship in Zhoushan. China J Med Virol. 2021;1:1–5. doi: 10.1002/jmv.27239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jiangsu Commission of Health. Reports of new confirmed cases of COVID-19. 2021. July 21, http://wjw.jiangsu.gov.cn/art/2021/7/21/art_7290_9893771.html. Accessed: 2021-7-21.

- 7.Sun G.Q., Wang S.F., Li M.T., Li L., Zhang J., Zhang W., et al. Transmission dynamics of COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: effects of lockdown and medical resources. Nonlin Dyn. 2020;101:1981–1993. doi: 10.1007/s11071-020-05770-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Neto O.P., Kennedy D.M., Reis J.C., Wang Y., Brizzi A.C.B., Zambrano G.J., et al. Mathematical model of COVID-19 intervention scenarios for Sao Paulo-Brazil. Nat Commun. 2021;12(1):418. doi: 10.21203/rs.3.rs-32962/v1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhu H., Li Y., Jin X., Huang J., Liu X., Qian Y., et al. Transmission dynamics and control methodology of COVID-19: a modeling study. Appl Math Model. 2021;89:1983–1998. doi: 10.1101/2020.03.29.20047118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kwuimy C.A.K., Nazari F., Jiao X., Rohani P., Nataraj C. Nonlinear dynamic analysis of an epidemiological model for COVID-19 including public behavior and government action. Nonlin Dyn. 2020;101:1545–1559. doi: 10.1007/s11071-020-05815-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Olaniyi S., Obabiyi O.S., Okosun K.O., Oladipo A.T., Adewale S.O. Mathematical modelling and optimal cost-effective control of COVID-19 transmission dynamics. Eur Phys J Plus. 2020;135(11):938. doi: 10.1140/epjp/s13360-020-00954-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Khan M.A., Atangana A. Modeling the dynamics of novel coronavirus (2019-nCov) with fractional derivative. Alex Eng J. 2020;59(4):2379–2389. doi: 10.1016/j.aej.2020.02.033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Asamoah J.K.K., Owusu M.A., Jin Z., Oduro F.T., Abidemi A., Gyasi E.O. Global stability and cost-effectiveness analysis of COVID-19 considering the impact of the environment: using data from Ghana. Chaos Soliton Fract. 2020;140:110103. doi: 10.1016/j.chaos.2020.110103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hezam I.M., Foul A., Alrasheedi A. A dynamic optimal control model for COVID-19 and cholera co-infection in Yemen. Adv Differ Equ-Ny. 2021;2021(1):108. doi: 10.1186/s13662-021-03271-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wickramaarachchi W.P.T.M., Perera S.S.N. An SIER model to estimate optimal transmission rate and initial parameters of COVD-19 dynamic in Sri Lanka. Alex Eng J. 2021;60(1):1557–1563. doi: 10.1016/j.aej.2020.11.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ullah S., Khan M.A. Modeling the impact of non-pharmaceutical interventions on the dynamics of novel coronavirus with optimal control analysis with a case study. Chaos Soliton Fract. 2020;139:110075. doi: 10.1016/j.chaos.2020.110075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang F., Qiu Z., Huang A., Zhao X. Optimal control and cost-effectiveness analysis of a Huanglongbing model with comprehensive interventions. Appl Math Model. 2021;90:719–741. doi: 10.1016/j.apm.2020.09.033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li T., Guo Y. Optimal control of an online game addiction model with positive and negative media reports. J Appl Math Comput. 2021;66(1):599–619. doi: 10.1007/s12190-020-01451-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alzahrani E.O., Ahmad W., Khan M.A., Malebary S.J. Optimal control strategies of Zika virus model with mutated. Commun Nonlin Sci. 2021;93:105532. doi: 10.1016/j.cnsns.2020.105532. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yıldız T.A., Karaoǧlu E. Optimal control strategies for tuberculosis dynamics with exogenous reinfections in case of treatment at home and treatment in hospital. Nonlin Dyn. 2019;97(4):2643–2659. doi: 10.1007/s11071-019-05153-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Driessche P.v.d., Watmough J. Reproduction numbers and sub-threshold endemic equilibria for compartmental models of disease transmission. Math Biosci. 2002;180:29–48. doi: 10.1016/S0025-5564(02)00108-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pontryagin L., Boltyanskii V., Gramkrelidze R., Mischenko E. Wiley Interscience; 1962. The mathematical theory of optimal processes. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.The seventh national census of China in 2020. 2020. http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjsj/tjgb/rkpcgb/, Accessed: 2021-05-11.

- 24.Kristensen M.R. Parameter estimation in nonlinear dynamical systems. Department of Chemical Engineering, Technical University of Denmark; 2004. Master’s thesis. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Khan M.A., Shah S.W., Ullah S., Gómez-Aguilar J.F. A dynamical model of asymptomatic carrier Zika virus with optimal control strategies. Nonlin Anal-Real. 2019;50:144–170. doi: 10.1016/j.nonrwa.2019.04.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lopez Bernal J., Andrews N., Gower C., Gallagher E., Simmons R., Thelwall S., et al. Effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines against the B.1.617.2 (Delta) variant. New Engl J Med. 2021;385(7):585–594. doi: 10.1056/NEJMdo006116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lauer S.A., Grantz K.H., Bi Q., Jones F.K., Zheng Q., Meredith H.R., et al. The incubation period of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) from publicly reported confirmed cases: estimation and application. Ann Intern Med. 2020;172(9):577–582. doi: 10.7326/M20-0504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Han S., Cai J., Yang J., Zhang J., Wu Q., Zheng W., et al. Time-varying optimization of COVID-19 vaccine prioritization in the context of limited vaccination capacity. Nat Commun. 2021;12:4673. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-24872-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Khan A., Zarin R., Hussain G., Ahmad N.A., Mohd M.H., Yusuf A. Stability analysis and optimal control of COVID-19 with convex incidence rate in Khyber Pakhtunkhawa (Pakistan) Results Phys. 2021;20:103703. doi: 10.1016/j.rinp.2020.103703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kolebaje O.T., Vincent O.R., Vincent U.E., McClintock P.V.E. Nonlinear growth and mathematical modelling of COVID-19 in some african countries with the Atangana-Baleanu fractional derivative. Commun Nonlin Sci Numer Simul. 2022;105:106076. doi: 10.1016/j.cnsns.2021.106076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Panwar V.S., Sheik Uduman P.S., Gómez-Aguilar J.F. Mathematical modeling of coronavirus disease COVID-19 dynamics using CF and ABC non-singular fractional derivatives. Chaos Soliton Fract. 2021;145:110757. doi: 10.1016/j.chaos.2021.110757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pandey P., Chu Y.M., Gómez-Aguilar J.F., Jahanshahi H., Aly A.A. A novel fractional mathematical model of COVID-19 epidemic considering quarantine and latent time. Results Phys. 2021;26:104286. doi: 10.1016/j.rinp.2021.104286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Khan M.S., Samreen M., Ozair M., Hussain T., Gómez-Aguilar J.F. Bifurcation analysis of a discrete-time compartmental model for hypertensive or diabetic patients exposed to COVID-19. Eur Phys J Plus. 2021;136(8):853. doi: 10.1140/epjp/s13360-021-01862-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gómez-Aguilar J.F., Alderremy A.A., Aly S., Saad K.M. A fuzzy fractional model of coronavirus (COVID-19) and its study with Legendre spectral method. Results Phys. 2021;21:103773. doi: 10.1016/j.rinp.2020.103773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Beigi A., Yousefpour A., Yasami A., Gómez-Aguilar J.F., Bekiros S., Jahanshahi H. Application of reinforcement learning for effective vaccination strategies of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) Eur Phys J Plus. 2021;136(5):609. doi: 10.1140/epjp/s13360-021-01620-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rahman M.U., Arfan M., Shah K., Gómez-Aguilar J.F. Investigating a nonlinear dynamical model of COVID-19 disease under fuzzy Caputo, random and ABC fractional order derivative. Chaos Soliton Fract. 2020;140:110232. doi: 10.1016/j.chaos.2020.110232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Khan M.A., Ullah S., Kumar S. A robust study on 2019-nCOV outbreaks through non-singular derivative. Eur Phys J Plus. 2021;136:168. doi: 10.1140/epjp/s13360-021-01159-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ramos A.M., Vela-Perez M., Ferrandez M.R., Kubik A.B., Ivorra B. Modeling the impact of SARS-CoV-2 variants and vaccines on the spread of COVID-19. Commun Nonlin Sci Numer Simul. 2021;102:105937. doi: 10.1016/j.cnsns.2021.105937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Freire-Flores D., Llanovarced-Kawles N., Sanchez-Daza A., Olivera-Nappa A. On the heterogeneous spread of COVID-19 in Chile. Chaos Soliton Fract. 2021;150:111156. doi: 10.1016/j.chaos.2021.111156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Planas D., Veyer D., Baidaliuk A., Staropoli I., Guivel-Benhassine F., Rajah M.M., et al. Reduced sensitivity of SARS-CoV-2 variant delta to antibody neutralization. Nature. 2021;596:276–280. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03777-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]