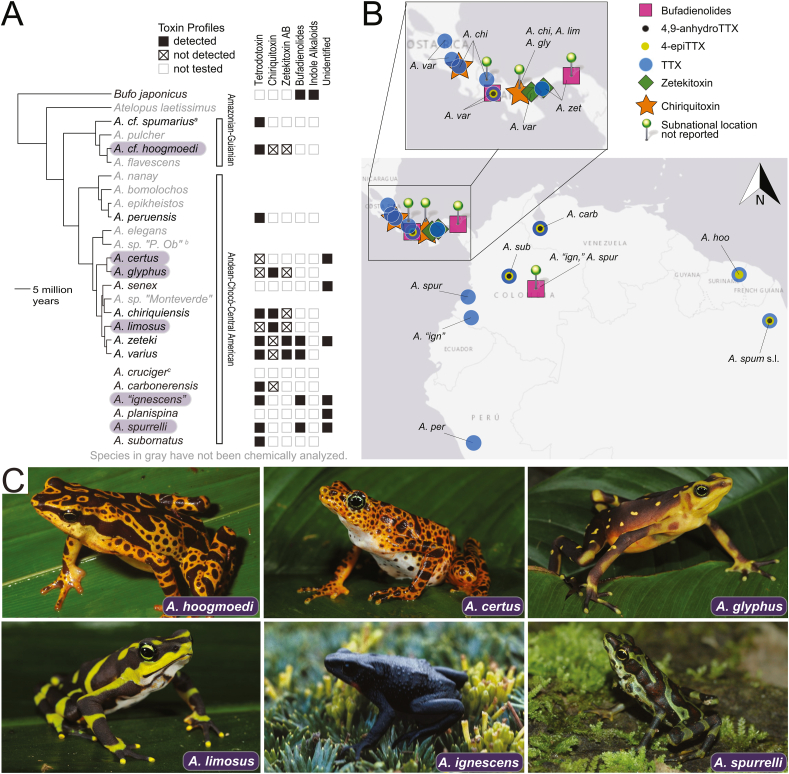

Fig. 3.

A) The phylogenetic distribution of toxic non-proteinaceous chemicals in skin, granular gland, and egg extracts of Atelopus. Bars to the right of the chronogram correspond to clades described by Lötters et al. (2011) and supported by Ramírez et al. (2020). Species listed below the chronogram were not included in the original phylogenetic analysis (Ramírez et al., 2020), and have been placed in the Andean-Chocó-Central American clade based on Lötters et al. (2011) and/or geographic range (Amphibiaweb, 2021). Species names highlighted in purple have corresponding images in Fig. 3c. a Whereas A. cf. spumarius samples from Ecuador were used in the estimation of the chronogram (Ramírez et al., 2020), the associated toxin profile data is derived from A. spumarius sensu lato collected in Colombia (Table S2; Daly et al., 1994). b “P. Ob” is an abbreviation of “Puerto Obaldia-Capurgana.” cA. cruciger are nontoxic (Mebs and Schmidt, 1989). References: Atelopus: See Table S1. Bufo japonicus: (Erspamer et al., 1964, Inoue et al., 2020). B) Geographic distribution of Atelopus toxins. Samples for which subnational data weren't reported (green pin) are mapped only when they are the sole sample containing a particular toxin collected from a given species in that country. The locations of these points were selected for ease of visualization. See Supplementary Table S2 for coordinate data. C) Selected images of Atelopus species which have been subjected to chemical analysis. Photo credits: A. hoogmoedi by Pedro L. V. Peloso via calphotos.berkeley.edu (© 2010, with permission); A. certus, A. glyphus, and A. limosus by Brian Freiermuth via calphotos.berkeley.edu (© 2013, with permission); A. ignescens by Luis A. Coloma via bioweb.bio (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), A. spurrelli by RD Tarvin (2014, Termales, Chocó, Colombia). For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.