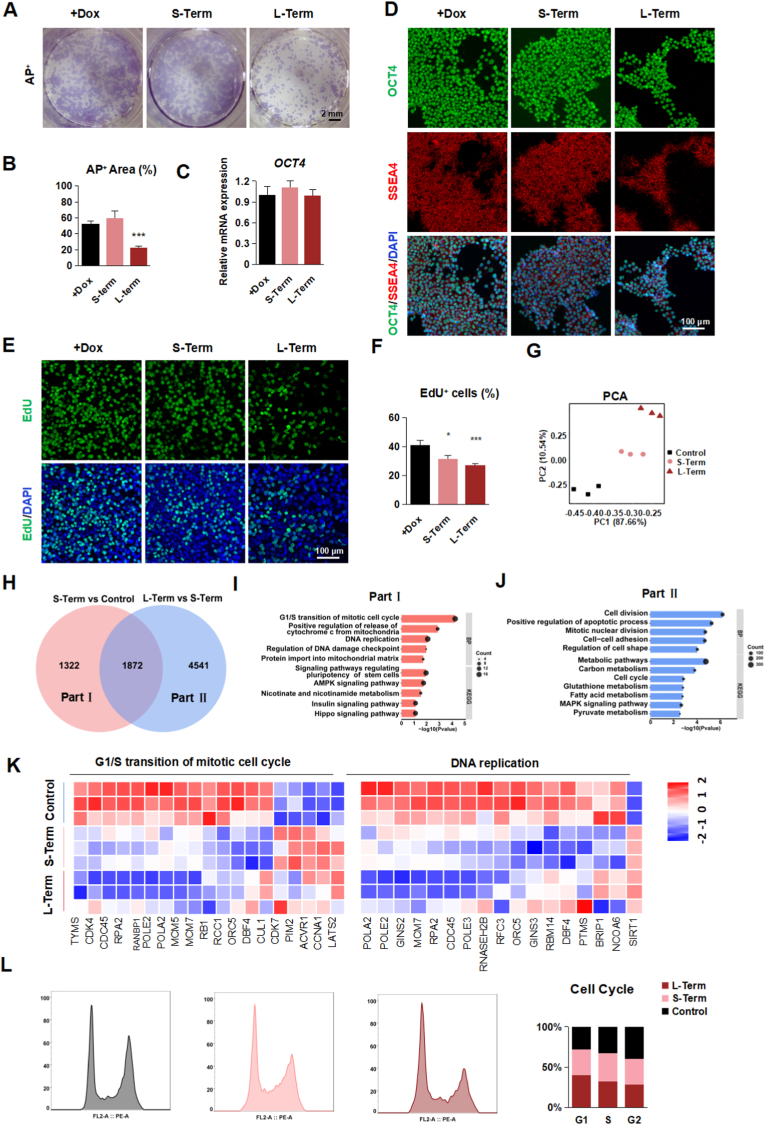

Fig. 2.

TFAM is critical for hPSC self-renewal

(A-B) Representative staining images (A) and quantification (B) of AP+ (purple) in TFAM-/- hPSCs treated with or without Dox. Scale bars, 2 mm. Data were shown as Mean ± SEM (n = 3, ***p < 0.001 compared with the +Dox group).

(C) Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of the expression level of OCT4 in TFAM-/- hPSCs treated with or without Dox. Data were shown as Mean ± SEM (n = 3).

(D) Representative immunostaining images for OCT4+ (green), SSEA4+ (red) and DAPI (blue) in TFAM-/- hPSCs treated with or without Dox. Scale bars, 100 μm.

(E–F) Representative immunostaining images (E) and quantification (F) of EdU+ (green) and DAPI (blue) in TFAM-/- hPSCs treated with or without Dox. Scale bars, 100 μm. Data were shown as Mean ± SEM (n = 8, *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001 compared with the +Dox group).

(G) PCA scatter plot of gene expression in group + Dox, Short-Term, and Long-Term. (n = 3).

(H) Venn diagram representation of the common pool of differentially regulated genes in three groups.

(I–J) GO and KEGG analysis in Part Ⅰ (I) and Part Ⅱ (J).

(K) The heatmap displays the Logarithm of fold change (Log2FC) in the G1/S transition of the mitotic cell cycle and DNA replication.

(L) Flow cytometry assessment of cell cycle in group +Dox, Short-Term, and Long-Term. (n = 3). (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)