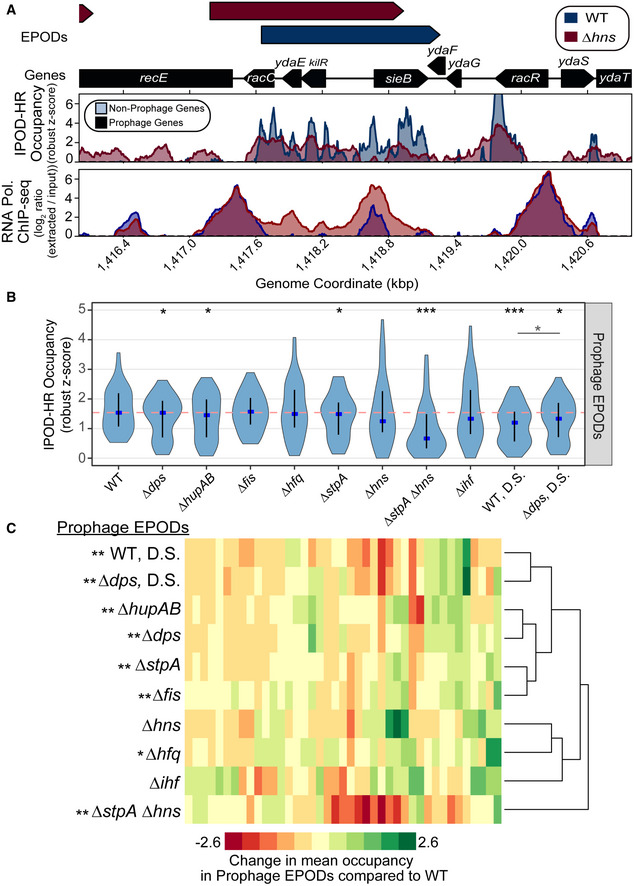

Figure 5. Nucleoid‐associated proteins contribute to protein occupancy at EPODs that contain prophages.

- IPOD‐HR occupancy and RNA polymerase occupancy over a known H‐NS silenced prophage in WT (blue) and ∆hns (red) cells. The quantile‐normalized robust z scores of the protein occupancy at each 5 bp are represented by the IPOD‐HR occupancy.

- The mean protein occupancy (IPOD‐HR occupancy) was calculated over WT EPOD locations that contain prophages (41 EPOD locations). As in Fig 2D, the blue dots denote the median and the black line displays the interquartile ranges in each condition. The dashed pink line represents the WT median. (*) indicate significance assessed via a Wilcoxon rank‐sum test comparing the change in pseudomedian versus WT for each condition (against a null hypothesis of no difference in medians), after application of a Benjamini–Hochberg correction for multiple hypothesis testing. The smaller horizontal line denotes the same comparison between the D.S. conditions. Q value < 0.05 = *, < 0.005=**, < 0.0005=***. Data were averaged across 2 (hupAB, fis, stpA, ihf, dps), 3 (WT, hfq, WT DS, dps DS), or 4 (hns, stpA/hns) biological replicates.

- Mean protein occupancy was calculated across all WT EPOD locations that contain annotated prophages. The change in mean protein occupancy compared to WT was calculated for each condition, where anything negative is a loss in occupancy compared to WT. Hierarchical clustering was performed to examine which genotypes clustered together and were more similar. Permutation tests comparing the change in occupancy over EPODs containing prophages were performed against the rest of the genome. P value < 0.05 = *, < 0.005 = ** indicate a negative mean change in occupancy compared to WT.