Abstract

Objective

The purpose of this review was to identify quality indicators described in the literature that may be used as quality measures in hospital physical therapy units.

Methods

The following sources were searched for quality indicators or articles: Web of Science, MEDLINE, IBECS, Latin American and Caribbean Health Sciences Literature, Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health, Academic Search Complete, SportDiscus, SciELO, PsychINFO, Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Cientificas, and Scopus databases; the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, National Health System Indicator Portal, Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations, and Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development websites; and the National Quality Forum’s measures inventory tool. Search terms included “quality indicator,” “quality measure,” “physiotherapy,” and “physical therapy.” Inclusion criteria were articles written in English, Spanish, French, or Portuguese aimed at measuring the quality of care in hospital physical therapy units. Evidence-based indicators with an explicit formula were extracted by 2 independent reviewers and then classified using the structure-process-outcome model, quality domain, and categories defined by a consensus method.

Results

Of the 176 articles identified, only 19 met the criteria. From these articles and from the indicator repository searches, 178 clinical care indicators were included in the qualitative synthesis and presented in this paper. Process and outcome measures were prevalent, and 5 out of the 6 quality domains were represented. No efficiency measures were identified. Moreover, structure indicators, equity and accessibility indicators, and indicators in the cardiovascular and circulatory, mental health, pediatrics, and intensive care categories were underrepresented.

Conclusions

A broad selection of quality indicators was identified from international resources, which can be used to measure the quality of physical therapy care in hospital units.

Impact

This review identified 178 quality of care indicators that can be used in clinical practice monitoring and quality improvement of hospital physical therapy units. The results highlight a lack of accessibility, equity, and efficiency measures for physical therapy units.

Keywords: Health Care, Hospital, Hospital Administration, Physical Therapy Department, Practice Management, Quality Assurance

Introduction

Quality of care concepts have long been promoted by the seminal works of Avedis Donabedian and other experts in the field,1–3 but they have not permeated every discipline or every country at the same pace. Quality of care is “the degree to which health services for individuals and populations increase the likelihood of desired health outcomes and are consistent with current professional knowledge.”4 This definition is further operationalized through 6 domains (accessibility, effectiveness, efficiency, equity, patient-centered care, and safety) proposed by the National Academy of Medicine4 and the World Health Organization.5 Besides, Donabedian’s structure-process-outcome model constitutes a must when measuring and improving quality.6 Both definition and model apply to all health care services and disciplines.

In this regard, some attempts have been proposed for providing a specific conceptual framework to the physical therapy discipline using the Donabedian model,7 though no consensus has been reached.8 In fact, instead of conceiving health care quality in physical therapy as an individual, separate conceptual framework, a proper understanding of the concept, and an operationalization of its dimensions in measurable aspects are needed. This will certainly contribute to add value to the physical therapy profession and to the health care system overall.

Physical therapy may benefit from the application of the existing framework to identify tools that measure structures, processes, and outcomes related to physical therapy in areas of urgent need for improvement such as patient education,9 efficiency in treatments and optimization of time with patients,10 further implementation of clinical reasoning in daily practice, and referrals to physical therapy.11,12 From a quality measurement and improvement perspective, these goals require standardized, evidence-based tools that can serve to evaluate, monitor, and guide clinical practice improvement.13 Such tools include quality indicators that quantify performance in relation to the aforementioned Donabedian elements of care by comparing them with evidence-based criteria for quality or any of its domains.4,5 Such measurement tools are necessary to guide decision-making and evaluate the success of physical therapy services, but physical therapists may not be aware of the extent to which measures exist. To the best of our knowledge, there is no systematic review on quality indicators for hospital physical therapy units.

The objective of this systematic review was to identify and describe quality indicators for use in hospital physical therapy units. A secondary objective was to present a classification matrix for categorizing quality indicators. Furthermore, as the first of a series about quality indicators for hospital physical therapy units, this paper focused on clinical care indicators for assessing evidence-based practices.

Methods

This systemic review was performed in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items of Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines,14 with 2 substantial modifications. First, we developed inclusion and exclusion criteria for both articles and indicators, the latter being the unit of analysis in our work. Second, we retrieved individual quality indicators from databases and web pages that serve as indicator repositories. The protocol of this review is registered at https://osf.io/ceybw (doi: 10.17605/OSF.IO/N569S).

Data Sources and Searches

A literature search was conducted using Web of Science, PubMed/MEDLINE, IBECS, LILACS, CINAHL, Academic Search Complete, SportDiscus, SciELO, PsycINFO, CSIC bibliographic databases, and Scopus. Additionally, we searched the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Indicators database, the United Kingdom’s National Health System Indicator portal, The Joint Commission website, the National Quality Forum’s measure inventory tool, and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development Health Statistics database. Searches were conducted between May and June of 2019.

Search strategies were predefined and created by the 2 principal investigators (D.A.G. and I.M.N.). Due to the a priori lack of quality indicators for physical therapy, we implemented a broad search strategy using the search strings (“quality indicator” OR “quality measure”) AND (“physiotherapy” OR “physical therapy”). Manual searches were used for web pages and repositories without a built-in search engine, and references from the most relevant studies were reviewed for additional papers.

Study Selection

Eligible articles included those written in English, Spanish, French, or Portuguese measuring the quality of care in hospital physical therapy units (eg, reviews of indicators, indicator development studies, health care evaluation studies, or studies of quality improvement interventions that included quality measures). Studies without explicitly described quality measures were excluded.

We identified potential quality indicators in the selected studies as those based on evidence (at least graded or stated by the authors) and with an explicit calculation formula described (a numerator and denominator or similar). Indicators that were not specific to physical therapy (eg, those aimed at the whole rehabilitation unit or specialties other than physical therapy) were excluded. Indicators that could not be used in the Spanish context due to legal or regulatory aspects of the physical therapy profession in Spain also were excluded. These criteria were similarly applied for the indicator databases and repositories.

After removing duplicates, 2 independent reviewers (D.A.G. and I.M.N.) selected articles by title using the Rayyan QCRI web application.15 If discrepancies arose, both reviewers discussed the adequacy of articles until they reached an agreement. The full texts (including annexes and additional materials) of the remaining articles were then reviewed.

Data Extraction

Two reviewers extracted the data (B.S. and A.M.). Discrepancies in data extraction were resolved by consensus. The following data were extracted from each indicator: name, reference, link, denominator, numerator, and level of evidence. We entered all data into an Excel spreadsheet.

Data Synthesis and Analysis

To synthesize the data, we first developed a classification matrix composed of 3 main taxonomy groups: the 3 elements of care (structure, process, and outcome),6 also known as the Donabedian model; the 6 health care quality domains (accessibility, effectiveness, efficiency, equity, patient-centered care, and safety) proposed by the National Academy of Medicine and the international community4,5 (see Tab. 1 for definitions); and specific categories of measurement in hospital physical therapy units, as defined through a consensus approach.

Table 1.

Definitions of the 6 Health Care Quality Domains by the World Health Organization

| Health Care Quality Domain | Description |

|---|---|

| Accessibility | Timely, geographically reasonable, and provided in a setting where skills and resources are appropriate to medical need |

| Acceptability or patient-centered care | Accounts for preferences and aspirations of individual service users and the cultures of their communities |

| Effectiveness | Adheres to an evidence base and results in improved health outcomes for individuals and communities, based on need |

| Efficiency | Maximizes resource use and avoids waste |

| Equity | Consistent in quality across personal characteristics such as gender, race, ethnicity, geographical location, or socioeconomic status |

| Safety | Minimizes risks and harm to service users |

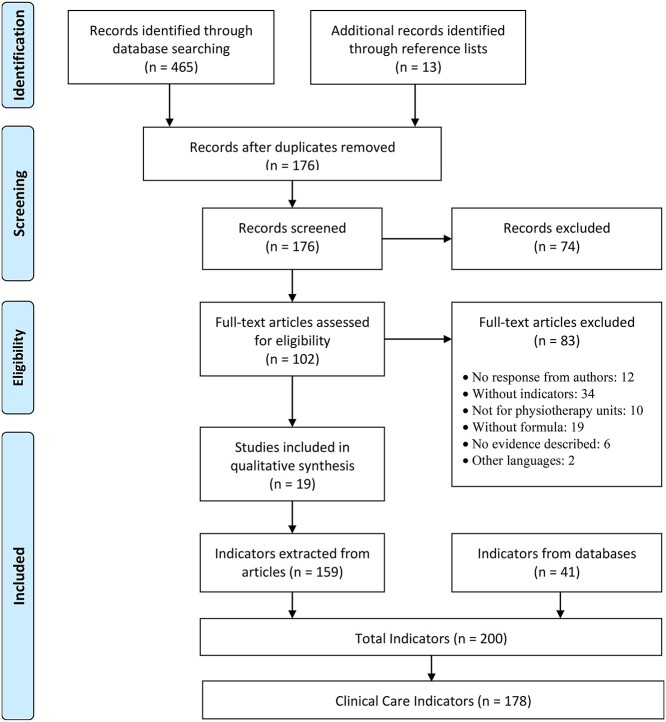

Next, a brainstorming session and nominal group technique16 were employed to identify and refine categories of measurement. Participants included 9 (3 male and 6 female; mean age 45.8 years) heads of physical therapy units at public hospitals who were in charge of 5 to 25 (mean: 13.3) physical therapists. All 9 participated in a working session guided by 2 quality management specialists. In the session, participants conducted 2 rounds of rating, discussion, and rerating. Categories identified in the first round were separated into 2 primary domains: clinical care and unit management. A final consensus was reached by establishing 13 pathology-related clinical care categories that were grouped in 3 applicability settings (ambulatory care, inpatient care, or both), and 10 management categories that could be distributed in 2 accountability perspectives (internal management for indicators related to workflow of the unit itself and external management for indicators related to relationships with other units and shared workflow). Figure 1 depicts the composition of this classification matrix.

Figure 1.

Classification matrix for quality indicators in hospital physical therapy units.

All indicators retrieved from searches were catalogued in the matrix. Indicators that could be classified in more than one quality domain were assigned to their primary domain to maintain clear categorizations. Their original titles were adapted and translated into Spanish, French, Italian, and English. Original levels of evidence also were translated into the Oxford Center of Evidence-Based Medicine scale,17 where Level 1 is the highest level of evidence and Level 5 the lowest. Only clinical indicators are presented in the current publication.

Role of the Funding Source

The funders played no role in the design, conduct, or reporting of this study.

Results

Literature and Indicator Searches

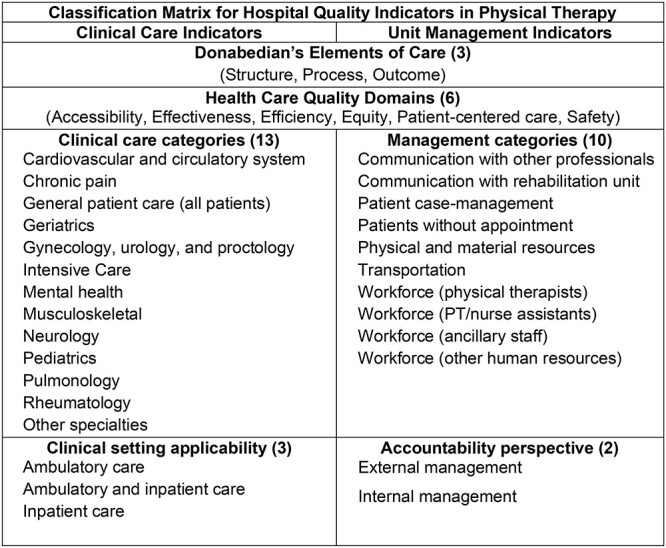

Figure 2 shows the Preferred Reporting Items of Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flow diagram. From the literature databases, we retrieved 465 articles, 176 of which were screened. After selecting by title and abstract, we reviewed the full text of 102 articles and selected 19 that met our criteria.18–37 These publications comprised 1 guideline,19 4 quality of care evaluations,18,22,32,37 and 14 indicator development articles,20,21,23–31,33–36 of which only 3 reported feasibility or reliability measurements.21,28,34 A total of 200 indicators were obtained, of which 178 were specific clinical care indicators (145 extracted from publications and 33 retrieved from repositories).

Figure 2.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram of the systematic review of hospital physical therapy quality indicators.

Classification of Quality Indicators for Hospital Physical Therapy Units

Table 2 shows the distribution of indicator type (Donabedian model), clinical care categories, clinical setting applicability, and quality of care domain. Regarding the 3 elements of care, process indicators were the most prevalent (n = 136; 76.4%), followed by outcome indicators (n = 40; 22.5%), and only 2 structure indicators were present.

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics for Clinical Care Indicators

| Characteristics | Donabedian Model |

Total (n = 178) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Structure (n = 2) |

Process (n = 136) |

Outcome (n = 40) |

||

| Clinical care category | ||||

| Cardiovascular and circulatory system | 0 (0%) | 1 (0.7%) | 1 (2.5%) | 2 (1.1%) |

| Chronic pain | 0 (0%) | 2 (1.5%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (1.1%) |

| General patient care (all patients) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 17 (42.5%) | 17 (9.6%) |

| Geriatrics | 0 (0%) | 22 (16.2%) | 1 (2.5%) | 23 (12.9%) |

| Gynecology, urology, proctology | 0 (0%) | 9 (6.6%) | 0 (0%) | 9 (5.1%) |

| Intensive care | – | – | – | 0 (0%) |

| Mental health | 0 (0%) | 1 (0.7%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (0.6%) |

| Musculoskeletal | 0 (0%) | 30 (22.1%) | 8 (20%) | 38 (21.4%) |

| Neurology | 1 (50%) | 7 (5.2%) | 5 (12.5%) | 13 (7.3%) |

| Pediatrics | – | – | – | 0 (0%) |

| Pulmonology | 1 (50%) | 37 (27.2%) | 5 (12.5%) | 43 (24.2%) |

| Rheumatology | 0 (0%) | 22 (16.2%) | 1 (2.5%) | 23 (12.9%) |

| Other specialties | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (2.5%) | 1 (0.6%) |

| Clinical setting applicability | ||||

| Ambulatory care | 1 (50%) | 38 (27.9%) | 5 (12.5%) | 44 (24.7%) |

| Ambulatory and inpatient care | 1 (50%) | 94 (69.1%) | 26 (65%) | 121 (68%) |

| Inpatient care | 0 (0%) | 4 (2.9%) | 9 (22.5%) | 13 (7.3%) |

| Health care quality domain | ||||

| Accessibility | 0 (0%) | 1 (0.7%) | 1 (2.5%) | 2 (1.1%) |

| Effectiveness | 1 (50%) | 114 (83.8%) | 32 (80%) | 147 (82.6%) |

| Efficiency | – | – | – | 0 (0%) |

| Equity | 1 (50%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (0.6%) |

| Patient-centered care | 0 (0%) | 11 (8.1%) | 2 (5%) | 13 (7.3%) |

| Safety | 0 (0%) | 10 (7.4%) | 5 (12.5%) | 15 (8.4%) |

| Level of evidence (Oxford Center of Evidence-Based Medicine) | ||||

| Level 1 | 1 (50%) | 44 (32.4%) | 2 (5%) | 47 (26.4%) |

| Level 2 | 0 (0%) | 14 (10.3%) | 4 (10%) | 18 (10.1%) |

| Level 3 | 0 (0%) | 20 (14.7%) | 4 (10%) | 24 (13.5%) |

| Level 4 | 0 (0%) | 8 (5.9%) | 4 (10%) | 12 (6.7%) |

| Level 5 | 1 (50%) | 50 (36.8%) | 26 (65%) | 77 (43.3%) |

They covered a wide range of clinical areas, though some areas were underrepresented, such as cardiovascular (n = 2; 1.1%), chronic pain (n = 2; 1.1%), mental health (n = 1; 0.5%), pediatrics (n = 0), and intensive care (n = 0). Four clinical areas accounted for 70% of the quality indicators: pulmonology (n = 43; 24.2%), musculoskeletal (n = 38; 21.4%), geriatrics (n = 29; 16.3%), and rheumatology (n = 23; 12.9%). Most indicators (n = 121; 68%) were applicable to both inpatient care and ambulatory care (Tab. 1).

Effectiveness was the most populated domain of quality of care (n = 147; 82.6%). Equity and efficiency were less populated, with 1 (0.6%) and 0 indicators, respectively.

In terms of level of evidence, the median was 3 (interquartile range = 1–5) for process indicators, 5 (interquartile range = 2–5) for outcome indicators, and 3 (one indicator with 1 and another with 5) for structure indicators. Table 3 shows examples of indicators with highest level of evidence (Level 3 to Level 1). The online supplementary material includes all clinical care indicators, along with their characteristics and a short title translated into English (available upon request with their translated titles in Spanish, French, and Italian).

Table 3.

Examples of Clinical Care Indicators by Health Care Quality Domain

| Domain | Description |

Level of Evidence |

Type of Indicator |

Category |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effectiveness | Percentage of vulnerable elderly with symptomatic knee or hip osteoarthritis for 3 mo and for which a directed or supervised program of muscle strengthening or aerobic exercise has been recommended | 1 | Process | Geriatrics |

| Percentage of women with urge urinary incontinence or overactive bladder who have been advised on behavior modification, including fluid restriction and bladder training | 1 | Process | Gynecology, urology, and proctology | |

| Percentage of patients diagnosed with vestibular function problems who have received vestibular rehabilitation | 1 | Process | Neurology | |

| Percentage of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease who completed a pulmonary rehabilitation program with at least a minimum number of sessions and whose functional capacity in 6-min walk test improved by at least 25 m | 1 | Outcome | Pulmonology | |

| Equity | Evidence that a pulmonary rehabilitation program admits patients who have previously had pulmonary rehabilitation | 1 | Structure | Pulmonology |

| Patient-centered care | Adjusted rate of change in admission-discharge self-care score in patients >21 y hospitalized with physical therapy treatment | 2 | Outcome | All patients |

| Safety | Fall rate with injury per 1000 patient d | 3 | Outcome | All patients |

| Percentage of vulnerable elderly people whose balance or proprioception decrease or who postural deviation increases for whom an adequate exercise program has been offered and need for an assistive device has been evaluated | 1 | Process | Geriatrics | |

| Percentage of vulnerable elderly patients who were asked about the occurrence of recent falls | 3 | Process | Geriatrics |

Discussion

We developed a systematic review of the literature databases and indicator databases to identify quality indicators for measuring and improving the quality of care of hospital physical therapy units. Our search yielded 178 evidence-based clinical care indicators classified into 13 categories, covering all 3 indicator types (structure, process, and outcome) and 5 of the 6 quality domains (accessibility, effectiveness, equity, patient-centered care, and safety). To classify these indicators, we developed a classification matrix composed of 4 taxonomy groups: Donabedian elements of care, quality of care domain, clinical care category, and clinical setting.

State of the Art of Physical Therapy Quality of Care Measurement

To our knowledge, no systematic review of physical therapy quality indicators has been published. In our results, process indicators were overrepresented, probably because they are easier to measure.2,38,39 However, these indicators usually cannot be used to infer quality of care unless there is an a priori establishment of a cause-and-effect relationship between the process and the outcome of interest,2 which is mostly warranted for the indicators in our study because we considered only those based on evidence and could be further appraised by the level of evidence of each one. Another reason for the overrepresentation might be the international favoring of process indicators to translate evidence into practice38,39 and the utilization of recent methods of quality improvement, such as clinical pathways40 or other process-oriented approaches.41

Structure measures were scarce in our results. Only 2 indicators were identified: 1 for a referral admission procedure from pulmonary rehabilitation and 1 for a complete record of complications in stroke patients. This paucity is striking given the importance of these basic structural components. In addition to human and material resource support, structural tools such as these also are crucial, particularly evidence-based decision-making tools (eg, clinical practice guidelines, protocols, and standardized assessments) that help to reduce variability of processes and enhance quality of care.42 Standardized assessments are instruments that are constructed, administered, scored, and interpreted in a consistent manner to ensure reliability and to quantify and document a patient’s baseline status, progress, and outcomes.43,44 Although the registering activity is a process, standardized assessments may be considered structural elements that should be prioritized in preliminary improvement initiatives.

Regarding their clinical purpose, a reasonable number of indicators applied to the main areas of practice in physical therapy (pulmonology, musculoskeletal conditions, geriatrics, and rheumatology), but no indicators were identified in other areas with critical impacts on patient health, such as cardiovascular45 or intensive care.46 In addition, some indicators in these areas might have key roles in efficiency strategies (eg, readmission avoidance or length-of-stay reduction), although readmission and length-of-stay measures should be considered as global efficiency outcomes affected by multidisciplinary workflow. Thus, methodological considerations apply when using these indicators.38,39

Indeed, efficiency indicators were totally absent from our results, and accessibility had little representation despite the extent of poor referrals in many contexts.47 Similarly, equity and patient-centered care seem to be neglected by current research and quality indicator developers, although recent work on patient-centered care in physical therapy could be a good framework for developing indicators in this critical issue.48,49

Scientific Soundness of Current Quality Indicators for Hospital Physical Therapy Units

The current methodological guides for quality indicators38,50–55 include at least 3 proposals to appraise quality indicators.52,56,57 Yet, we found few indicators with an exhaustive validation and pilot-testing background. Only 3 articles reported a pilot test and data on reliability or feasibility of their indicators.20,27,34 None addressed important elements such as the impact of data gathering on routine clinical practice, predefined standards, or risk-adjustment methods.38,55 These 3 elements relate closely to the contextual circumstances of each health care center, its needs, and its capabilities. So, even with well-developed quality indicators, it is recommended to assess these characteristics and judge the need for adapting them to a new care setting. Specifically, reviewing and adapting international indicators or indicators new to a team who intends to use them is advisable to ensure the measurement tool will be accepted by the professionals involved in quality improvement initiatives. The literature offers several examples of this review and adaptation process,51,58 which can serve as guides for physical therapists who are less experienced in quality management.

Implications for Practice (How to Use Quality Indicators)

An extensive collection of quality indicators has been developed for physical therapy. We encourage those in charge of physical therapy units to select 1 or more indicators presented in this study to measure their unit’s activity. To make these selections, consensus methods (eg, nominal group technique, modified-Delphi) could be used.14 A pilot test is also advisable. The literature cited in this study can be useful for these purposes.

A training in quality assessment and improvement should be included in entry level and continuing education for physical therapists. To this end, and to help support naïve teams in starting quality improvement activities, we recommend contacting a quality manager in the hospital.

Limitations

We did not conduct a critical appraisal of the indicators, which are thus subject to variability in reliability, feasibility, and usefulness. However, we established eligibility criteria to ensure proper, evidence-based indicators with explicit formulas. Furthermore, our classification helps to recognize the purpose of the indicator and provide an initial framework for quality measurement and improvement in hospital physical therapy units. Nonetheless, the classification matrix needs further validation by experts from different countries to generalize its use in different contexts, such as diverse hospital structures and across the various roles of physical therapists.

The physical therapy discipline has access to a broad selection of quality indicators, mainly in the process and outcome domains. These indicators cover most clinical areas (exceptions include cardiovascular and circulatory system, mental health, pediatrics, and intensive care areas). Accessibility, efficiency, and equity indicators are still lacking. More research is necessary to provide proven, evidence-based quality measures to fill the identified gaps and determine how indicators can be implemented in everyday practice. Using currently available measures, physical therapists at hospitals can start evaluating and improving quality of care in their units.

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Daniel Angel-Garcia, Department of Physiotherapy, Catholic University of Murcia (UCAM), Guadalupe, Murcia, Spain.

Ismael Martinez-Nicolas, Department of Physiotherapy, Catholic University of Murcia (UCAM), Guadalupe, Murcia, Spain.

Bianca Salmeri, Department of Physiotherapy, Catholic University of Murcia (UCAM), Guadalupe, Murcia, Spain.

Alizée Monot, Department of Physiotherapy, Catholic University of Murcia (UCAM), Guadalupe, Murcia, Spain.

Author Contributions

Concept/idea/research design: D. Angel-Garcia, I. Martinez-Nicolas, B. Salmeri, A. Monot

Writing: D. Angel-Garcia, I. Martinez-Nicolas, B. Salmeri, A. Monot

Data collection: D. Angel-Garcia, I. Martinez-Nicolas, A. Monot

Data analysis: D. Angel-Garcia, I. Martinez-Nicolas, A. Monot

Project management: D. Angel-Garcia, A. Monot

Fund procurement: D. Angel-Garcia, I. Martinez-Nicolas

Consultation (including review of manuscript before submitting): D. Angel-Garcia, I. Martinez-Nicolas, A. Monot

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the heads of the 9 public physical therapy units involved in this project for all of their support during indicator prioritization and development of the categorization matrix: Antonio San Martin, Francisco Rodríguez Jiménez, Juana María Cerdá Tomás, Manoli García Alcaraz, María de los Ángeles Martínez de Salazar Arboleas, María Encarnación Melgarejo Gonzalez-Conde, María Isabel Novas Gutiérrez, Miguel Díaz Serrano, and Silvia Vázquez Giménez. The authors also thank the Spanish General Council of Physical Therapy and Juan Sánchez Garre for their support.

Funding

This work was supported by the Fundación Española de Calidad Asistencial (FECA) [grant number 2018/2].

Systematic Review Registration

The protocol of this review is registered at OSF Registries (https://osf.io/ceybw – doi: 10.17605/OSF.IO/N569S).

Disclosures

The authors completed the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest and reported no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1. Lohr KN. Medicare: A Strategy for Quality Assurance. Washington, DC, USA: National Academy Press; 1990. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Donabedian A. An Introduction to Quality Assurance in Health Care. New York, NY, USA: Oxford University Press Inc; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rodkey GV, Itani KMF. Evaluation of healthcare quality: a tale of three giants. Am J Surg. 2009;198:S3–S8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Institute of Medicine (IOM) . Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, DC, USA: National Academies Press; 2001. http://www.nap.edu/catalog.php?record_id=10027. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. World Health Organization . In: Bengoa R, Kawar R, Key P, Leatherman S, Massoud R, Saturno P, eds., Quality of Care: A Process for Making Strategic Choices in Health Systems. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Donabedian A. The quality of care. How can it be assessed? JAMA. 1988;260:1743–1748. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3045356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Jesus TS, Hoenig H. Postacute rehabilitation quality of care: toward a shared conceptual framework. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2015;96:960–969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Strasser DC. Medical aspects of disability for the rehabilitation professional. In: Moroz A, Flanagan SR, Zaretsky H, eds. Medical Aspects of Disability for the Rehabilitation Professional. 5th ed. New York, NY, USA: Springer Publishing Company; 2016:773–786. doi: 10.1891/9780826132284 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Forbes R, Mandrusiak A, Smith M, Russell T. A comparison of patient education practices and perceptions of novice and experienced physiotherapists in Australian physiotherapy settings. Musculoskelet Sci Pract. 2017;28:46–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Traeger AC, Moynihan RN, Maher CG. Wise choices: making physiotherapy care more valuable. J Physiother. 2017;63:63–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hensher M. Improving general practitioner access to physiotherapy: a review of the economic evidence. Health Serv Manag Res. 1997;10:225–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Piscitelli D, Furmanek MP, Meroni R, De Caro W, Pellicciari L. Direct access in physical therapy: a systematic review. Clin Ter 2018;169:e249–e260. doi: 10.7417/CT.2018.2087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Westby MD, Klemm A, Li LC, Jones CA. Emerging role of quality indicators in physical therapist practice and health service delivery. Phys Ther. 2016;96:90–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and Meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000097. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, Elmagarmid A. Rayyan—a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst Rev. 2016;5:210. 10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Fink A, Kosecoff J, Chassin M, Brook RH. Consensus methods: characteristics and guidelines for use. Am J Public Health. 1984;74:979–983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Jeremy H, Iain C, Paul G et al. The Oxford Levels of Evidence 2. 2011. Accessed January 17, 2022. https://www.cebm.ox.ac.uk/resources/levels-of-evidence/ocebm-levels-of-evidence.

- 18. Anger JT, Alas A, Litwin MS et al. The quality of care provided to women with urinary incontinence in 2 clinical settings. J Urol. 2016;196:1196–1200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. British Thoracic Society (BTS) . Quality Standards for Pulmonary Rehabilitation in Adults. Vol 6. London, UK: British Thoracic Society; 2014. https://www.brit-thoracic.org.uk/document-library/quality-standards/pulmonary-rehabilitation/bts-quality-standards-for-pulmonary-rehabilitation-in-adults/. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Mac Lean CH, Pencharz JN, Saag KG. Quality indicators for the care of osteoarthritis in vulnerable elders. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55:S383–S391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Minaya-Muñoz F, Medina-Mirapeix F, Valera-Garrido F. Quality measures for the care of patients with lateral epicondylalgia. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2013;14:310. 10.1186/1471-2474-14-310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Østerås N, Jordan KP, Clausen B et al. Self-reported quality care for knee osteoarthritis: comparisons across Denmark, Norway, Portugal, and the UK. RMD Open. 2015;1:e000136. 10.1136/rmdopen-2015-000136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Peter WF, Hurkmans EJ, van der Wees PJ, Hendriks EJM, van Bodegom-Vos L, Vliet Vlieland TPM. Healthcare quality indicators for physiotherapy management in hip and knee osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis: a Delphi study. Musculoskeletal Care. 2016;14:219–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Petersson IF, Strömbeck B, Andersen L et al. Development of healthcare quality indicators for rheumatoid arthritis in Europe: the eumusc.net project. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73:906–908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Rizk H, Agrawal Y, Barthel S et al. Quality improvement in neurology: neurotology quality measurement set. Otolaryngol Neck Surg. 2018;159:603–607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Rubenstein LZ, Powers CM, Mac Lean CH. Quality indicators for the management and prevention of falls and mobility problems in vulnerable elders. Ann Intern Med. 2001;135:686. 10.7326/0003-4819-135-8_Part_2-200110161-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Salvat-Plana M, Abilleira S, Jiménez C, Marta J, Gallofré M. Priorización de indicadores de calidad de la atención al paciente con ictus a partir de un método de consenso. Rev Calid Asist. 2011;26:174–183. 10.1016/j.cali.2010.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Saturno PJ, Ángel-García D, Martínez-Nicolás I et al. Development and pilot test of a new set of good practice indicators for chronic nonmalignant pain management. Pain Pract. 2019;19:37–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Schnelle JF, Smith RL. Quality indicators for the management of urinary incontinence in vulnerable community-dwelling elders. Ann Intern Med. 2001;135:752. 10.7326/0003-4819-135-8_Part_2-200110161-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Cavalheiro LV, Eid RAC, Talerman C, Prado C, do, Gobbi, Andreoli PB de FCM, A. Design of an instrument to measure the quality of care in physical therapy. Einstein (São Paulo). 2015;13:260–268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Chang JT, Ganz DA. Quality indicators for falls and mobility problems in vulnerable elders. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55:S327–S334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Evans DW, Breen AC, Pincus T et al. The effectiveness of a posted information package on the beliefs and behavior of musculoskeletal practitioners. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2010;35:858–866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Grossman JM. Quality indicators for the management of osteoporosis in vulnerable elders. Ann Intern Med. 2001;135:722. 10.7326/0003-4819-135-8_Part_2-200110161-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Grube MM, Dohle C, Djouchadar D et al. Evidence-based quality indicators for stroke rehabilitation. Stroke. 2012;43:142–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Güell MR, Cejudo P, Rodríguez-Trigo G et al. Estándares de calidad asistencial en rehabilitación respiratoria en pacientes con enfermedad pulmonar crónica. Arch Bronconeumol. 2012;48:396–404.22835266 [Google Scholar]

- 36. Khanna D, Arnold EL, Pencharz JN et al. Measuring process of arthritis care: the Arthritis Foundation’s quality indicator set for rheumatoid arthritis. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2006;35:211–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Livingstone I, Hefele J, Nadash P, Barch D, Leland N. The relationship between quality of care, physical therapy, and occupational therapy staffing levels in nursing homes in 4 years’ follow-up. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2019;20:462–469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Mainz J. Developing evidence-based clinical indicators: a state of the art methods primer. Int J Qual Health Care. 2003;15:i5–i11 http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14660518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Rubin HR, Pronovost P, Diette GB. The advantages and disadvantages of process-based measures of health care quality. Int J Qual Health Care. 2001;13:469–474 http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11769749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Richter P, Schlieter H. Process-based quality management in care: adding a quality perspective to pathway modelling. In: Lecture Notes in Computer Science (Including Subseries Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence and Lecture Notes in Bioinformatics). Vol 11877 LNCS. New York, NY, USA: Springer; 2019:385–403. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-33246-4_25 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Vos L, Chalmers SE, Dückers MLA, Groenewegen PP, Wagner C, van Merode GG. Towards an organisation-wide process-oriented organisation of care: a literature review. Implement Sci. 2011;6:8. 10.1186/1748-5908-6-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Institute of Medicine (IOM) . Clinical Practice Guidelines We Can Trust. Washington, DC, USA: The National Academies Press; 2011. http://nap.edu/catalog.php?record_id=13058. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Duncan PW, Zorowitz R, Bates B et al. Management of adult stroke rehabilitation care. Stroke. 2005;36:e100–e143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Waltz CF, LE Strickland OL. Standardized approaches to measurement. In: Measurement in Nursing Research. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA, USA: F.A. Davis; 1991: 257–288. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Huang R, Palmer SC, Cao Y et al. Cardiac rehabilitation programs for chronic heart disease: a Bayesian network meta-analysis. Can J Cardiol. 2021;37:162–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Herbsman JM, D’Agati M, Klein D et al. Early mobilization in the pediatric intensive care unit: a quality improvement initiative. Pediatr Qual Saf. 2020;5:e256. 10.1097/pq9.0000000000000256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Hatamabadi HR, Sum S, Tabatabaey A, Sabbaghi M. Emergency department management of falls in the elderly: a clinical audit and suggestions for improvement. Int Emerg Nurs. 2016;24:2–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Wijma AJ, Bletterman AN, Clark JR et al. Patient-centeredness in physiotherapy: what does it entail? A systematic review of qualitative studies. Physiother Theory Pract. 2017;33:825–840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Cheng L, Leon V, Liang A et al. Patient-centered care in physical therapy: definition, operationalization, and outcome measures. Phys Ther Rev. 2016;21:109–123. [Google Scholar]

- 50. Kötter T, Blozik E, Scherer M. Methods for the guideline-based development of quality indicators—a systematic review. Implement Sci. 2012;7:21. 10.1186/1748-5908-7-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Stelfox HT, Straus SE. Measuring quality of care: considering conceptual approaches to quality indicator development and evaluation. J Clin Epidemiol. 2013;66:1328–1337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Shekelle PG. Quality indicators and performance measures: methods for development need more standardization. J Clin Epidemiol. 2013;66:1338–1339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Stelfox HT, Straus SE. Measuring quality of care: considering measurement frameworks and needs assessment to guide quality indicator development. J Clin Epidemiol. 2013;66:1320–1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Center for Health Policy/Center for Primary Care and Outcomes Research and Battelle Memorial Institute . Quality Indicator Measure Development, Implementation, Maintenance, and Retirement. Rockville, MD, USA: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 55. Rubin HR, Pronovost P, Diette GB. From a process of care to a measure: the development and testing of a quality indicator. Int J Qual Health Care. 2001;13:489–496 http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11769752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Perera R, Dowell T, Crampton P, Kearns R. Panning for gold: an evidence-based tool for assessment of performance indicators in primary health care. Health Policy (New York). 2007;80:314–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. De Koning J. Development and validation of a measurement instrument for appraising indicator quality: appraisal of indicators through research and evaluation (AIRE) instrument. Paper presented in: Kongress Medizin Und Gesellschaft 2007. Düsseldorf, Germany: German Medical Science GMS Publishing House; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 58. Campbell SM, Braspenning J, Hutchinson A, Marshall M. Research methods used in developing and applying quality indicators in primary care. Qual Saf Health Care. 2002;11:358–364. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=1758017&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.