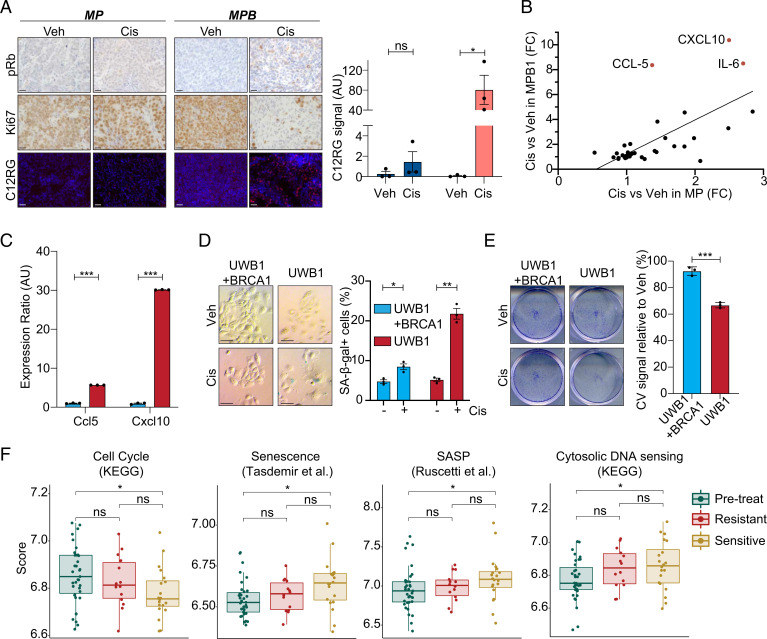

Fig. 3.

Cisplatin treatment preferentially induces tumor cell senescence and alters immune infiltrates in HR-deficient HGSOC. (A) Immunohistochemical staining of phospho-Rb (pRb) and Ki67 and staining of C12RG, a fluorogenic substrate for SA-β-gal activity, of subcutaneously transplanted tumors treated with vehicle or cisplatin. (Scale bar, 20 µm.) Quantification of SA-β-gal activity is shown on the Right (n = 3). (B) Cytokine expression in MP (x axis) or MPB1 (y axis) cell lines treated with cisplatin relative to vehicle (n = 2 independent cell lines per genotype). (C) RT-qPCR analysis of Ccl5 and Cxcl10 in cisplatin-treated BRCA1-proficient (UWB1 + BRCA1) or -deficient (UWB1) human ovarian cancer cells (n = 3 technical replicates). (D) SA-β-gal staining (Left) and quantification (Right) of either BRCA1-proficient (UWB1 + BRCA1) or -deficient (UWB1) human ovarian cancer cell lines after treatment with vehicle or 100 nM cisplatin for 6 d (n = 3). (Scale bar, 50 µm.) (E) Clonogenic crystal violet (CV) assay of human ovarian cancer cells replated in the absence of drugs after 6-d pretreatment as in D (n = 3). (F) Expression of senescence and SASP signatures in patient samples isolated pretreatment and after three cycles of chemotherapy during the Cambridge Translational Cancer Research Ovarian Study 01 (CTCR-OV01) clinical trial (49, 50) (GSE15622). Posttreatment samples are subdivided into resistant and sensitive cases. *P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01, ***P ≤ 0.001, ns: not significant; mean ± SEM; analyses performed using unpaired t test (A and C–E) and Wilcoxon signed-rank test (F).