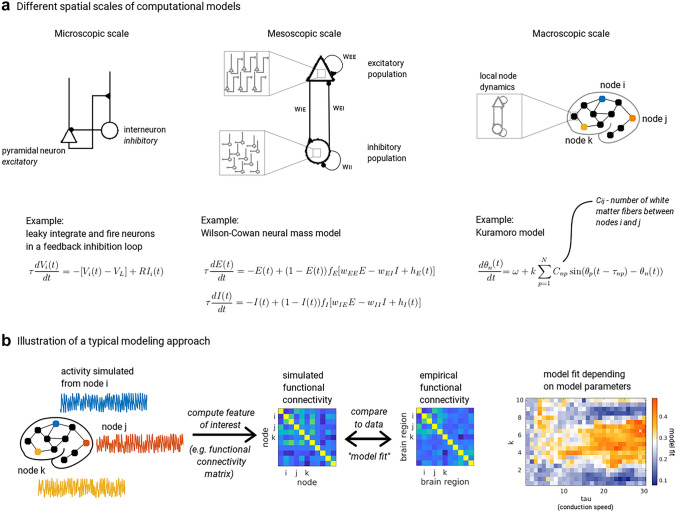

Fig. 2.

a Illustration of computational models at the three scales treated here. Microscopic scale: Simple example of two () leaky integrate-and-fire (LIF) neurons coupled together, a pyramidal neuron making an excitatory synapse to the interneuron, which in turn makes an inhibitory synapse to the pyramidal cell. This minimal circuit implements feedback inhibition, as the pyramidal cell, when activated, will excite the interneuron, which in turn will inhibit it. In the equation, is the membrane potential of each of the two cells ; is the leak, or resting potential of the cells; R is a constant corresponding to the membrane resistance; is the synaptic input that each cell receives from the other, and possibly background input; is the time constant determining how quickly decays. The model is simulated by setting a firing threshold, at which, when reached, a spike is recorded and is reset to . Mesoscopic scale: The Wilson–Cowan-model, in which an excitatory (E) and an inhibitory (I) population are coupled together. The mean field equations describe the mean activity of a large number of neurons. and are sigmoid transfer functions whose values indicate how many neurons in the population reach firing threshold, and / are external inputs like background noise. and are constants correponding to the strength of self-excitation/inhibition, and and the strength of synaptic coupling between populations. Macroscopic scale: In order to simulate long-range interactions between cortical and even subcortical areas, brain network models couple together many mesoscopic (“local”) models using the connection weights defined in the empirical structural connectivity matrix C. The example equation defines the Kuramoto model, in which the phase of each node n is used as a summary of its oscillatory activity around its natural frequency . Each node’s phase depends on the phases of connected nodes p taking into account the time delay , defined by the distances between nodes n and p. k is a global scaling parameter controlling the strength of internode connections. b Illustration of a typical modeling approach at the macroscopic scale. Activity is simulated for each node using the defined macroscopic model, e.g. the Kuramoto model from panel a, right. The feature of interest is then computed from this activity. Shown here is the functional connectivity, e.g., phase locking values between nodes (Table 1). This can then be compared to the empirical functional connectivity matrix computed in exactly the same way from experimental data, e.g. by correlating the entries of the matrix. The model fit can be determined depending on parameters of the model, e.g. the scaling parameter k or the unit speed, here indicated with “tau”