Abstract

Objective

To describe the clinical data from the first 108 patients seen in the Mayo Clinic post–COVID-19 care clinic (PCOCC).

Methods

After Institutional Review Board approval, we reviewed the charts of the first 108 patients seen between January 19, 2021, and April 29, 2021, in the PCOCC and abstracted from the electronic medical record into a standardized database to facilitate analysis. Patients were grouped into phenotypes by expert review.

Results

Most of the patients seen in our clinic were female (75%; 81/108), and the median age at presentation was 46 years (interquartile range, 37 to 55 years). All had post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection, with 6 clinical phenotypes being identified: fatigue predominant (n=69), dyspnea predominant (n=23), myalgia predominant (n=6), orthostasis predominant (n=6), chest pain predominant (n=3), and headache predominant (n=1). The fatigue-predominant phenotype was more common in women, and the dyspnea-predominant phenotype was more common in men. Interleukin 6 (IL-6) was elevated in 61% of patients (69% of women; P=.0046), which was more common than elevation in C-reactive protein and erythrocyte sedimentation rate, identified in 17% and 20% of cases, respectively.

Conclusion

In our PCOCC, we observed several distinct clinical phenotypes. Fatigue predominance was the most common presentation and was associated with elevated IL-6 levels and female sex. Dyspnea predominance was more common in men and was not associated with elevated IL-6 levels. IL-6 levels were more likely than erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein to be elevated in patients with post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Abbreviations and Acronyms: COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; CRP, C-reactive protein; CRS, cytokine release syndrome; CS, central sensitization; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; IL, interleukin; PASC, post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection; PCOCC, post–COVID-19 care clinic; PoCoS, post-COVID syndrome; POTS, postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2

Since its identification in December 2019, the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), which causes coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), has had a devastating global impact with more than 4.7 million deaths worldwide as of September 2021. In addition to mortality, patients have been left with significant debility after recovering from acute COVID-19. The earliest report of this condition was a case series from Italy of 143 patients who had been hospitalized for COVID-19. In this population, persistent symptoms were observed for 60 days from initial onset in 87.4% of cases, with a predominance of fatigue (53.1%), dyspnea (43.4%), joint pain (27.3%), and chest pain (21.7%) during outpatient follow-up.1 These findings were confirmed in a subsequent 6-month cohort study of 1733 patients from Wuhan, China, which again reported persistent fatigue or muscle weakness (63%) as well as sleep difficulties (26%) and anxiety and depression (23%).2 Recent studies have estimated that between 10% and 30% of patients who recover from COVID-19 experience persistent symptoms months after resolution of acute illness.1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 These persistent symptoms have been described by several terms, including post-COVID syndrome (PoCoS), post–acute COVID-19, and long-haul COVID.4, 5, 6, 7 The National Institutes of Health developed the term post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection (PASC) to describe those patients with COVID-19 who have at least 1 symptom that developed after the acute infection and has persisted after the expected resolution of acute disease.

Direct organ damage from COVID-19 has been observed in PASC patients with single-system involvement, such as anosmia, cardiomyopathy, neuropathy, or interstitial lung disease. Causes of disability beyond lingering effects of direct organ damage include widespread pain, fatigue with postexertional malaise, orthostatic intolerance, and cognitive impairment including the commonly reported “brain fog.” This cluster of symptoms is similar to that seen in other postinfectious syndromes, which may progress to fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue syndrome, postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS), and other central sensitization (CS) syndromes. These CS syndromes are thought to share a common pathophysiologic mechanism with central neuroinflammation and remodeling of brain and spinal cord pathways leading to enhanced sensitivity to multiple stimuli, sympathetic hyperactivity, and decreased efficacy of inhibitory pathways.8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19

Research in CS has recently turned to the role of proinflammatory mediators in the development and persistence of these conditions.20 Prominent cytokine and chemokine elevations have included interleukin (IL) 6, IL-8, IL-17, IL-1β, and tumor necrosis factor α.20, 21, 22 High-sensitivity C-reactive protein (CRP) has been found to be comparably elevated in both fibromyalgia and chronic fatigue syndrome, with mixed data on elevated CRP.23 Not surprisingly, there has been similar interest in the cytokine release syndrome (CRS) attributed to severe cases of COVID-19, especially in regard to IL-6.24 The potential overlap between the inflammatory response of CS and PASC has not yet been determined.

In response to the COVID-19 pandemic and the rising cases of PASC, our institution developed a multispecialty team to coordinate efforts and to share clinical and research approaches to PASC. This multispecialty team is composed of physicians and scientists from general internal medicine, preventive medicine, physical medicine and rehabilitation, psychology, allergy and immunology, infectious disease, pulmonology, neurology, cardiology, pediatrics, and otorhinolaryngology services. Subspecialists experienced in acute COVID-19 and PASC directly see patients with symptoms limited to their specific organ system, whereas the general internal medicine and preventive medicine clinics evaluate patients with multiple affected systems.25

Herein we describe the clinical presentation and associated laboratory findings from our inaugural cohort of 108 patients seen in the post–COVID-19 care clinic (PCOCC).

Methods

Patients

The study was approved by the Mayo Clinic COVID-19 Research Taskforce and the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board. The data for all patients in the PCOCC who had provided research authorization were entered into a prospectively maintained internal REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture) database. Patients seen between January 19, 2021, and April 29, 2021, were included. Acute symptoms (within the first 4 weeks of COVID-19 diagnosis or symptom onset) were recorded, followed by chronic symptoms (those persisting beyond 4 weeks from diagnosis or symptom onset). Laboratory and other diagnostic testing data (protocol described later) were also collected as available.

Statistical Analyses

Data were abstracted from the electronic medical record and entered into a REDCap database.26 , 27 Patients’ clinical symptoms were analyzed by reviewers, and they were assigned to 1 of 6 phenotypes: dyspnea, chest pain, myalgia, orthostasis, fatigue, and headache predominant. Laboratory data were entered from the electronic medical record exactly with 1 exception as the lower limit of CRP in our laboratory is reported as less than 3.0 μg/L. As we could not identify exact values of data below this threshold, this value was entered as 3.0 throughout in REDCap. Data were then analyzed using χ 2 analysis to identify differences between phenotypes for categorical values such as sex and analysis of variance to identify differences between phenotypes for quantitative data.

Care Team Design

Patients who had persistent symptoms after COVID-19 infection were either self-referred or physician referred to the PCOCC. All patients completed a standardized questionnaire that contains 52 questions about initial COVID-19 infection, symptoms, and treatment along with ongoing and persistent symptoms that continue to affect them. Patient questionnaires were reviewed by a general internal medicine physician, and those with symptoms limited to a single organ system were directly referred to the subspecialty team for management of PASC symptoms; for example, patients with anosmia were referred directly to the otorhinolaryngology service. Patients with symptoms in multiple organ systems were initially evaluated by a 30-minute virtual visit for the purpose of introducing the PCOCC and appropriate preordering of tests and consultations. Patients would then be evaluated in person during a condensed itinerary of tests and consultations geared toward the predominant symptoms. Patients with no evidence of tissue damage on testing were likely to have a CS phenotype, which was treated with a virtual treatment program aimed at patient education with elements of cognitive-behavioral therapy, health coaching, and paced rehabilitation. This program is 8 hours long, delivered as two 4-hour segments, and accompanied by health coaching and nursing follow-up for 6 months.

As part of the PCOCC evaluation, the team developed a standardized evaluation to be ordered for any patient presenting to the clinic. This included basic laboratory testing (complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel, erythrocyte sedimentation rate [ESR], CRP), markers of COVID-19 inflammation (ferritin, D-dimer, IL-6), autoimmune screening (antinuclear antibody and CRP with reflex to full panel if response to either is positive), 6-minute walk test, and pulmonary function tests and chest imaging if the patient had dyspnea.

Results

Demographic Characteristics of the Patients

The first 108 patients evaluated by our PCOCC team were included. Of these, 81 (75%) were female, with a median age of 46 years (interquartile range, 37 to 55 years). The average female age was slightly younger than in the overall cohort at 45 years. Of our patients, 94% (102) were White/Caucasian, 4% (4) were Black/African American, and 2% (2) were American Indian/Pacific Islander; 98% (106) of our patients identified as non-Hispanic, and 2% (2) were Hispanic (Table 1 ). The most common comorbidities identified in our population were obesity (42 [39%]), anxiety (36 [33%]), depression (30 [28%]), and gastrointestinal disease (27 [25%]). Symptoms reported most commonly in the acute COVID-19 infection included fatigue (64 [59%]), cough (58 [54%]), shortness of breath (56 [52%]), and myalgia (54 [50%]; Supplemental Table 1, available online at http://www.mayoclinicproceedings.org); 16% of our population was admitted for acute COVID-19. Patients were evaluated in our clinics on average 148.5 days after the onset of symptoms (interquartile range, 111.5 to 179.3 days). At the time of evaluation, the most common symptoms were fatigue (96 [89%]), shortness of breath (75 [69%]), brain fog (74 [69%]), anxiety (67 [62%]), and unrefreshing sleep (63 [58%]; Supplemental Table 2, available online at http://www.mayoclinicproceedings.org).

Table 1.

| Characteristic | (N=108) |

|---|---|

| Age (y) | 46 (37-55) |

| Sex | |

| Female | 81 (75) |

| Male | 27 (25) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Non-Hispanic | 106 (98) |

| Hispanic | 2 (2) |

| Race | |

| White | 102 (94) |

| African/African American | 4 (4) |

| Asian | 0 (0) |

| Pacific Islander | 0 (0) |

| American Indian/Native American | 2 (2) |

| Comorbidities | |

| Psychiatric disorder | 45 (42) |

| Anxiety | 36 (33) |

| Depression | 30 (28) |

| Obesity (BMI >30 kg/m2) | 42 (39) |

| Gastrointestinal disease | 27 (25) |

| IBS | 5 (5) |

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 19 (18) |

| Asthma | 13 (12) |

| Headache | 16 (15) |

| Diabetes | 15 (14) |

| Cardiovascular disease | 11 (10) |

| Coronary artery disease | 4 (4) |

| Stroke | 2 (2) |

| Arrhythmia | 2 (2) |

| Time since symptom onset (d) | 148.5 (111.5-179.3) |

| Admitted for COVID | 16 (16) |

BMI, body mass index; COVID, coronavirus disease; IBS, irritable bowel syndrome; PCOCC, post–COVID-19 care clinic.

Categorical variables are presented as number (percentage). Continuous variables are presented as median (interquartile range).

Phenotypes

Six phenotypes were identified (Table 2 ): fatigue predominant (n=69), dyspnea predominant (n=23), myalgia predominant (n=6), orthostasis predominant (n=6), chest pain predominant (n=3), and headache predominant (n=1). Distribution of phenotypes by sex was unequal, with more women being predominant for fatigue (58/69 [84%]), orthostasis (6/6 [100%]), and chest pain (3/3 [100%]). More men were predominant for dyspnea (12/23 [52%]) and headache (1/1 [100%]). Myalgia-predominant phenotype was evenly distributed between sexes (3/3 [50%]). These sex differences by phenotype were statistically significant (P=.0004).

Table 2.

| Phenotype | Patients | Women | P value, phenotype by sexd | IL-6 (pg/mL) | P value, phenotype by IL-6e | CRP (mg/L) | P value, phenotype by CRPe | ESR (mm/h) | P value, phenotype by ESRe | Time since onset of symptoms (d) | P value, phenotype by time since onsete |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chest pain | 3 | 3 | .0004 | 1.3 (0.3) | .0009 | 3 (0) | .11 | 3 (1.7) | .18 | 141.3 (43.5) | .29 |

| Dyspnea | 23 | 11 | 1.7 (0.9) | 4.9 (3.7) | 9.1 (7.8) | 155.7 (43.2) | |||||

| Fatigue | 69 | 58 | 2.5 (1.1) | 5.9 (5.3) | 13.5 (12.1) | 147.8 (53.3) | |||||

| Myalgia | 6 | 3 | 4.9 (3.8) | 16.04 (28.6) | 12.25 (14.1) | 157.2 (40.9) | |||||

| Orthostasis | 6 | 6 | 2.9 (0.4) | 6.5 (3.9) | 21.8 (20.8) | 106.2 (36.2) | |||||

| Headachef | 1 | 0 | 34 (0) | 42 (0) | |||||||

| Total | 108 | 81 | |||||||||

| Central sensitization | 82 | 67 | <.0001 | 2.8 (1.6) | .01 | 7.0 (9.6) | .32 | 14.2 (13.1) | .06 | 154 (42.6) | .45 |

| Not central sensitization | 26 | 14 | 1.6 (0.9) | 4.6 (3.4) | 8.1 (7.5) | 145.4 (52.3) |

CRP, C-reactive protein; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; IL-6, interleukin 6; PCOCC, post–COVID-19 care clinic.

To convert CRP values to nmol/L, multiply by 9.524.

Values are reported as mean (standard deviation).

P value by χ2 test.

P value by analysis of variance.

One patient with headache who had elevated ESR and CRP; IL-6 not measured.

Laboratory Markers

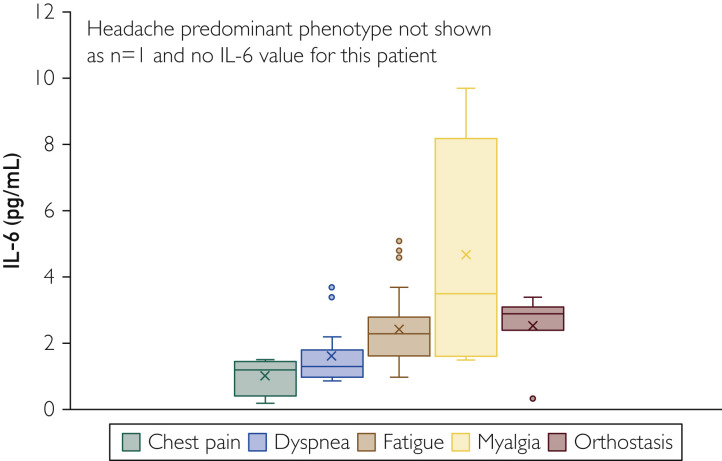

Laboratory markers varied significantly (Supplemental Figure 1, available online at http://www.mayoclinicproceedings.org; Table 2), with IL-6 elevated in a higher proportion of patients (61%) than CRP (17%) and ESR (20%). Interleukin 6 was elevated in a statistically significant proportion of women (69% vs 39% in men; P=.05), whereas there were no statistically significant differences in elevated ESR (18% in women vs 26% in men; P=.76) and CRP (15% in women vs 21% in men) between the sexes (Supplemental Table 3, available online at http://www.mayoclinicproceedings.org; Table 3 ). Laboratory markers also varied by phenotype, with IL-6 levels being more elevated in patients with the fatigue-predominant, myalgia-predominant, and orthostasis-predominant phenotypes (Figure 1 ).

Table 3.

Elevated Inflammatory Markers by Sex

| Test | No. elevated (No. with result) | Women | P value (elevated inflammatory marker by sex) |

|---|---|---|---|

| IL-6 | 41 (67 [61%]) | 34 (49 [69%]) | .046 |

| CRP | 12 (71 [17%]) | 8 (52 [15%]) | .72 |

| ESR | 14 (69 [20%]) | 9 (50 [18%]) | .76 |

CRP, C-reactive protein; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; IL-6, interleukin 6.

Figure 1.

Interleukin 6 (IL-6) levels in patients by clinic phenotype. Headache-predominant phenotype is not shown (n=1 and no IL-6 value for this patient).

Central Sensitization

The fatigue-predominant, myalgia-predominant, and orthostasis-predominant phenotypes were considered together as CS phenotypes, given their similarity across groups as well as similarity to existing CS conditions of chronic fatigue syndrome, fibromyalgia, and POTS. When considered together against the non-CS phenotype (dyspnea and chest pain [n=26]), the CS phenotype (n=82) had statistically significantly higher IL-6 levels (P=.01) and higher ESR and CRP levels, but these did not reach statistical significance (Supplemental Figure 2, available online at http://www.mayoclinicproceedings.org; Table 2). The CS phenotype also had a statistically significantly higher proportion of women (82%) than the non-CS phenotype (54%; P<.0001). Age was not significantly different between patients with CS (mean 45.7 years, SD 13.6 years) and patients without CS (mean 48.7 years, SD 14.8 years).

Discussion

The main objective of the PCOCC is to phenotype and then to treat PASC patients who are struggling with persistent symptoms for more than 3 months. There are 3 major novel findings from the first 108 PASC patients seen in the PCOCC: (1) there is female predominance in the patients seeking care for PASC (n=81 [75%]); (2) women are more likely than men to have an elevated IL-6 (69% vs 28%); and (3) ongoing fatigue is the most common phenotype in women (n=58 [72%]) and dyspnea the most common in men (n=12 [52%]). Most patients seen in the PCOCC did not have clear end-organ disease or damage to account for the ongoing symptoms, and CS phenotype (fatigue, myalgia, orthostasis) was the most common categorization. Of patients with CS phenotypes, 67 of 82 were women (82%), consistent with the known female predominance in CS (Table 2).28 , 29

The majority (n=62 [57%]) of patients seen in the PCOCC had elevated levels of the proinflammatory cytokine IL-6 at least 3 months after acute infection, which was highly discordant with ESR and CRP levels. To our knowledge, this has not been described in PASC. Acute COVID-19 infection has demonstrated a pattern of inflammatory response similar to but more pronounced than in other CRSs, such as sepsis, burns, and acute respiratory distress syndrome. The CRS response includes important components of the innate immune system, such as IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, and monocyte chemoattractant protein 1.30, 31, 32, 33, 34 This innate hyperinflammatory CRS response seen during severe COVID-19 is thought to be the primary mechanism behind adverse outcomes. In addition, IL-6 has been independently associated with mortality in COVID-19 patients requiring mechanical ventilation.24 It has been postulated that IL-6 inhibits antiviral activity, and blockade has been identified as a potential therapeutic target34 , 35; however, recent trials of tocilizumab, a monoclonal antibody against IL-6 receptor alpha, in hospitalized patients with COVID-19 have had mixed results.36 , 37 Further research is needed to determine whether IL-6 levels correlate with PASC symptom severity and resolution.

This study found that the persistent (>3-month) elevation in IL-6 level was more frequent in women, and we hypothesize that this could be partially responsible for the sex differences observed in PASC.38, 39, 40, 41, 42 Sex is one of several variables known to influence the overall immune responses to COVID-19. In a number of acute COVID-19 cohort studies, men had higher rates of hospitalization, critical illness, and mortality when adjusted for comorbidities and age.39 , 42 , 43 A cohort study of hospitalized COVID-19–positive patients who had not received immunomodulatory medications and had detailed cytokine, chemokine, and blood cell phenotyping samples compared with healthy controls found that men had a higher innate inflammatory response (IL-8 and IL-18) than women; but when women had elevated innate immune responses, it positively correlated with disease progression.43 Sex-based differences in the immune response vary throughout the life cycle, with postpuberty/premenopausal women having higher levels of inflammatory cytokines (IL-6, tumor necrosis factor, and IL-1β) compared with postpuberty/adult men. These effects may be mediated by sex hormones estradiol, progesterone, and androgens as this difference changes in older age, with men having higher inflammatory cytokine levels as they age.43, 44, 45

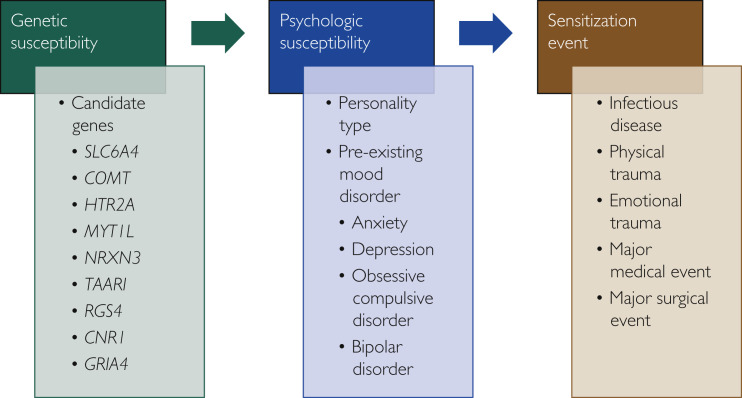

Many patients seen in the PCOCC have clinical presentations similar to those of other CS phenotypes, such as fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue syndrome, and POTS.46, 47, 48, 49, 50 Symptoms also overlap with the post–intensive care syndrome and postinfectious syndromes such as posttreatment Lyme disease syndrome.46 , 51 This centrally sensitized subset of PASC patients is referred to as having PoCoS. The presence of a common pathway mediated by immune dysregulation provides a common cause of these conditions, and IL-6 is elevated in these syndromes.52, 53, 54, 55, 56 Interleukin 6 is associated with fatigue and sleep disturbance in chronic stress and inflammation in CS syndromes.57 Diagnosis of these conditions has traditionally been frustrating as patients will have multiple disabling symptoms yet will have few (if any) abnormalities on laboratory and procedural testing. The most compelling explanation is that of CS, wherein the brain and spinal cord become more sensitive to stimuli, thereby reducing the stimulus threshold for perception and amplifying existing stimuli.58 Changes in the areas of the brain recruited secondary to a standard stimulus vary significantly between healthy controls and those with CS on both positron emission tomography/computed tomography and functional magnetic resonance imaging of the brain.59, 60, 61, 62 Besides commonalities in clinical presentation, persistent elevation of immune markers, and changes in functional imaging, patients often display symptoms of persistent sympathetic system hyperactivity with palpitations, exercise intolerance, difficulty in initiating and maintaining sleep, and sensitivity to external stimuli.47, 48, 49, 50 A familial predisposition to CS syndromes has been reported, with up to a 13-fold increase in incidence of CS compared with the general population.63 This suggests a genetic component to CS, which has been supported by several studies identifying genes that occur at a higher frequency in patients with CS, with fibromyalgia being the best studied of these syndromes.63 , 64 Finally, in our experience, patients affected by these syndromes also share personality traits, often describing themselves as “people pleasers” and “detail oriented.”58 Indeed, there has been some overlay between the genetics of fibromyalgia and anxiety, and these conditions are highly comorbid.65 With these considerations in mind, we propose a “3-hit” hypothesis wherein patients need to have the appropriate candidate genes to have the potential for development of CS, the personality type associated with CS, and then a “sensitizing event” that causes significant systemic distress, often viral in nature but that may include other forms of trauma (life events, physical trauma, surgery, major medical illness; Figure 2 ). The symptoms predominant during the sensitization event often remain predominant in the illness phenotype, but other symptoms may develop as the illness progresses. This expansion of symptoms is likely to be related to secondary changes, including impaired sleep and the distress and concern due to the impact of symptoms on life and physical activities.

Figure 2.

Proposed "3-hit" model for development of central sensitization.

This study had several limitations. First, the study design is a prospective cohort without strict inclusion criteria, which allows heterogeneity across the sample population. This was intentional as the general internal medicine clinic is best suited for evaluating patients with symptoms across multiple systems. Second, the selection of patients with multiple symptoms increased the concentration of patients with PoCoS as patients with limited symptoms suggestive of 1 organ system involvement or those with already identified post-COVID end-organ damage were directly triaged to the appropriate specialty (eg, anosmia to the otorhinolaryngology service, pulmonary fibrosis to the pulmonology service). This was also intentional as we had designed a treatment program directed at helping these individuals. Third, our population was either self-referred or provider referred, which may introduce an element of selection bias, thereby diminishing generalizability to the general population. Fourth, our population was 94% White/Caucasian and involved no patients of Hispanic descent. This was unintentional and probably secondary to our local demographic and differences in health-seeking behaviors. Therefore, future research in a more diverse population is warranted. Fifth, the standard laboratory panel was not ordered in all patients, which reflects referring provider preference or patient-specific clinical decisions. Because of these limitations, our study data may not be widely generalizable to all PASC patients but provide previously unreported insights into PoCoS and its likely immune dysregulation etiology.

Conclusion

In our PCOCC, we observed 6 distinct clinical phenotypes, of which the fatigue- and dyspnea-predominant phenotypes were most common in women and men, respectively. The phenotypes resembling known CS syndromes (fatigue, myalgia, and orthostasis predominant) were collectively considered PoCoS. This phenotype was associated with elevated IL-6, predominantly occurred in women, and presented with 3 major subtypes—fatigue, myalgia, and orthostasis. Knowledge of these phenotypes and the insights gleaned from the clinical data reported in this study may help in defining etiology and treatment options for PoCoS.

Footnotes

For editorial comment, see page 429

Grant Support: REDCap software provided by internal grant UL1TR002377.

Potential Competing Interests: A.D.B. is supported by grants from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (AI110173 and AI120698), amfAR (109593), and Mayo Clinic (HH Sheik Khalifa Bib Zayed Al-Nahyan Named Professorship of Infectious Diseases). A.D.B. is a paid consultant for Abbvie and Flambeau Diagnostics; is a paid member of the Data and Safety Monitoring Board for Corvus Pharmaceuticals, Equillium, and Excision Biotherapeutics; has received fees for speaking for Reach MD; owns equity for scientific advisory work in Zentalis and Nference; and is founder and President of Splissen Therapeutics. R.T.H. is a consultant for Nestle.

Data Previously Presented: A preliminary report of this work was previously published on medRxiv, June 2, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.05.25.21257820

Supplemental material can be found online at http://www.mayoclinicproceedings.org. Supplemental material attached to journal articles has not been edited, and the authors take responsibility for the accuracy of all data.

Supplemental Online Material

References

- 1.Carfì A., Bernabei R., Landi F. Persistent symptoms in patients after acute COVID-19. JAMA. 2020;324(6):603–605. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.12603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Garrigues E., Janvier P., Kherabi Y., et al. Post-discharge persistent symptoms and health-related quality of life after hospitalization for COVID-19. J Infect. 2020;81(6):e4–e6. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.08.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Greenhalgh T., Knight M., A'Court C., Buxton M., Husain L. Management of post–acute covid-19 in primary care. BMJ. 2020;370:m3026. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m3026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ladds E., Rushforth A., Wieringa S., et al. Persistent symptoms after Covid-19: qualitative study of 114 "long Covid" patients and draft quality principles for services. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20(1):1144. doi: 10.1186/s12913-020-06001-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ladds E., Rushforth A., Wieringa S., et al. Developing services for long COVID: lessons from a study of wounded healers [erratum appears in Clin Med (Lond). 2021;21(2):160] Clin Med (Lond) 2021;21(1):59–65. doi: 10.7861/clinmed.2020-0962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Logue J.K., Franko N.M., McCulloch D.J., et al. Sequelae in adults at 6 months after COVID-19 infection [erratum appears in JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(3):e214572] JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(2) doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.0830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Townsend L., Dyer A.H., Jones K., et al. Persistent fatigue following SARS-CoV-2 infection is common and independent of severity of initial infection. PLoS One. 2020;15(11) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0240784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cook R.L., Xu X., Yablonsky E.J., et al. Demographic and clinical factors associated with persistent symptoms after West Nile virus infection. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2010;83(5):1133–1136. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2010.09-0717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Duvignaud A., Fianu A., Bertolotti A., et al. Rheumatism and chronic fatigue, the two facets of post-chikungunya disease: the TELECHIK cohort study on Reunion island. Epidemiol Infect. 2018;146(5):633–641. doi: 10.1017/S0950268818000031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Islam M.F., Cotler J., Jason L.A. Post-viral fatigue and COVID-19: lessons from past epidemics. Fatigue. 2020;8(2):61–69. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kristiansen M.S., Stabursvik J., O'Leary E.C., et al. Clinical symptoms and markers of disease mechanisms in adolescent chronic fatigue following Epstein-Barr virus infection: an exploratory cross-sectional study. Brain Behav Immun. 2019;80:551–563. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2019.04.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leis A.A., Grill M.F., Goodman B.P., et al. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha signaling may contribute to chronic West Nile virus post-infectious proinflammatory state. Front Med (Lausanne) 2020;7:164. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2020.00164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moldofsky H., Patcai J. Chronic widespread musculoskeletal pain, fatigue, depression and disordered sleep in chronic post-SARS syndrome; a case-controlled study. BMC Neurol. 2011;11:37. doi: 10.1186/1471-2377-11-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pedersen M., Asprusten T.T., Godang K., et al. Predictors of chronic fatigue in adolescents six months after acute Epstein-Barr virus infection: a prospective cohort study. Brain Behav Immun. 2019;75:94–100. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2018.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pedersen M., Asprusten T.T., Godang K., et al. Fatigue in Epstein-Barr virus infected adolescents and healthy controls: a prospective multifactorial association study. J Psychosom Res. 2019;121:46–59. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2019.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rodriguez-Morales A.J., Simon F. Chronic chikungunya, still to be fully understood. Int J Infect Dis. 2019;86:133–134. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2019.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sejvar J.J., Curns A.T., Welburg L., et al. Neurocognitive and functional outcomes in persons recovering from West Nile virus illness. J Neuropsychol. 2008;2(2):477–499. doi: 10.1348/174866407x218312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sepulveda N., Carneiro J., Lacerda E., Nacul L. Myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome as a hyper-regulated immune system driven by an interplay between regulatory T cells and chronic human herpesvirus infections. Front Immunol. 2019;10:2684. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.02684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shikova E., Reshkova V., Kumanova A., et al. Cytomegalovirus, Epstein-Barr virus, and human herpesvirus-6 infections in patients with myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome. J Med Virol. 2020;92(12):3682–3688. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ji R.R., Nackley A., Huh Y., Terrando N., Maixner W. Neuroinflammation and central sensitization in chronic and widespread pain. Anesthesiology. 2018;129(2):343–366. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000002130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Banfi G., Diani M., Pigatto P.D., Reali E. T cell subpopulations in the physiopathology of fibromyalgia: evidence and perspectives. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(4):1186. doi: 10.3390/ijms21041186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Theoharides T.C., Tsilioni I., Bawazeer M. Mast cells, neuroinflammation and pain in fibromyalgia syndrome. Front Cell Neurosci. 2019;13:353. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2019.00353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Groven N., Fors E.A., Reitan S.K. Patients with fibromyalgia and chronic fatigue syndrome show increased hsCRP compared to healthy controls. Brain Behav Immun. 2019;81:172–177. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2019.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Popadic V., Klasnja S., Milic N., et al. Predictors of mortality in critically ill COVID-19 patients demanding high oxygen flow: a thin line between inflammation, cytokine storm, and coagulopathy. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2021;2021:6648199. doi: 10.1155/2021/6648199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vanichkachorn G., Newcomb R., Cowl C.T., et al. Post–COVID-19 syndrome (long haul syndrome): description of a multidisciplinary clinic at the Mayo Clinic and characteristics of the initial patient cohort. Mayo Clin Proc. 2021;96(7):1782–1791. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2021.04.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Harris P.A., Taylor R., Minor B.L., et al. The REDCap consortium: building an international community of software platform partners. J Biomed Inform. 2019;95:103208. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2019.103208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Harris P.A., Taylor R., Thielke R., Payne J., Gonzalez N., Conde J.G. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Meester I., Rivera-Silva G.F., Gonzalez-Salazar F. Immune system sex differences may bridge the gap between sex and gender in fibromyalgia. Front Neurosci. 2019;13:1414. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2019.01414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wolfe F., Walitt B., Perrot S., Rasker J.J., Hauser W. Fibromyalgia diagnosis and biased assessment: sex, prevalence and bias. PLoS One. 2018;13(9) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0203755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lorenz G., Moog P., Bachmann Q., et al. Cytokine release syndrome is not usually caused by secondary hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in a cohort of 19 critically ill COVID-19 patients. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):18277. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-75260-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Han H., Ma Q., Li C., et al. Profiling serum cytokines in COVID-19 patients reveals IL-6 and IL-10 are disease severity predictors. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2020;9(1):1123–1130. doi: 10.1080/22221751.2020.1770129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ingraham N.E., Lotfi-Emran S., Thielen B.K., et al. Immunomodulation in COVID-19. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8(6):544–546. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30226-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lagunas-Rangel F.A., Chavez-Valencia V. High IL-6/IFN-γ ratio could be associated with severe disease in COVID-19 patients. J Med Virol. 2020;92(10):1789–1790. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mazzoni A., Salvati L., Maggi L., et al. Impaired immune cell cytotoxicity in severe COVID-19 is IL-6 dependent. J Clin Invest. 2020;130(9):4694–4703. doi: 10.1172/JCI138554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Behm F.G., Jin M., Mohapatra G., Barkhordar F., Gavin I.M., Gillis B.S. Interleukin deficiency disorder patient responses to COVID-19 infections. J Adv Med Med Res. 2021;33(8):40–45. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Salama C., Han J., Yau L., et al. Tocilizumab in patients hospitalized with Covid-19 pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(1):20–30. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2030340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stone J.H., Frigault M.J., Serling-Boyd N.J., et al. Efficacy of tocilizumab in patients hospitalized with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(24):2333–2344. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2028836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Huang Y., Pinto M.D., Borelli J.L., et al. COVID symptoms, symptom clusters, and predictors for becoming a long-hauler: looking for clarity in the haze of the pandemic. medRxiv. 2021 doi: 10.1101/2021.03.03.21252086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Klein S.L., Dhakal S., Ursin R.L., Deshpande S., Sandberg K., Mauvais-Jarvis F. Biological sex impacts COVID-19 outcomes. PLoS Pathog. 2020;16(6) doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1008570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Klein S.L., Flanagan K.L. Sex differences in immune responses. Nat Rev Immunol. 2016;16(10):626–638. doi: 10.1038/nri.2016.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rubin R. As their numbers grow, COVID-19 "long haulers" stump experts. JAMA. 2020;324(14):1381–1383. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.17709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sudre C.H., Murray B., Varsavsky T., et al. Attributes and predictors of long COVID [erratum appears in Nat Med. 2021;27(6):1116] Nat Med. 2021;27(4):626–631. doi: 10.1038/s41591-021-01292-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Takahashi T., Ellingson M.K., Wong P., et al. Sex differences in immune responses that underlie COVID-19 disease outcomes. Nature. 2020;588(7837):315–320. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2700-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kragholm K., Andersen M.P., Gerds T.A., et al. Association between male sex and outcomes of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)—a Danish nationwide, register-based study. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;73(11):e4025–e4030. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Raza H.A., Sen P., Bhatti O.A., Gupta L. Sex hormones, autoimmunity and gender disparity in COVID-19. Rheumatol Int. 2021;41(8):1375–1386. doi: 10.1007/s00296-021-04873-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Aucott J.N., Rebman A.W. Long-haul COVID: heed the lessons from other infection-triggered illnesses. Lancet. 2021;397(10278):967–968. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00446-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Blitshteyn S., Whitelaw S. Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS) and other autonomic disorders after COVID-19 infection: a case series of 20 patients [erratum appears in Immunol Res. 2021;69(2):212.] Immunol Res. 2021;69(2):205–211. doi: 10.1007/s12026-021-09185-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Poenaru S., Abdallah S.J., Corrales-Medina V., Cowan J. COVID-19 and post-infectious myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome: a narrative review. Ther Adv Infect Dis. 2021;8 doi: 10.1177/20499361211009385. 20499361211009385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Raj S.R., Arnold A.C., Barboi A., et al. Long-COVID postural tachycardia syndrome: an American Autonomic Society statement. Clin Auton Res. 2021;31(3):365–368. doi: 10.1007/s10286-021-00798-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wong T.L., Weitzer D.J. Long COVID and myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS)—a systemic review and comparison of clinical presentation and symptomatology. Medicina (Kaunas) 2021;57(5):418. doi: 10.3390/medicina57050418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stam H.J., Stucki G., Bickenbach J. Covid-19 and post intensive care syndrome: a call for action. J Rehabil Med. 2020;52(4) doi: 10.2340/16501977-2677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fletcher M.A., Zeng X.R., Barnes Z., Levis S., Klimas N.G. Plasma cytokines in women with chronic fatigue syndrome. J Transl Med. 2009;7:96. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-7-96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jason L.A., Cotler J., Islam M.F., Sunnquist M., Katz B.Z. Risks for developing myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome in college students following infectious mononucleosis: a prospective cohort study. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;73(11):e3740–e3746. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.O'Mahony L.F., Srivastava A., Mehta P., Ciurtin C. Is fibromyalgia associated with a unique cytokine profile? Rheumatology (Oxford) 2021;60(6):2602–2614. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keab146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Vernino S., Stiles L.E. Autoimmunity in postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome: current understanding. Auton Neurosci. 2018;215:78–82. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2018.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mousa R.F., Al-Hakeim H.K., Alhaideri A., Maes M. Chronic fatigue syndrome and fibromyalgia-like symptoms are an integral component of the phenome of schizophrenia: neuro-immune and opioid system correlates. Metab Brain Dis. 2021;36(1):169–183. doi: 10.1007/s11011-020-00619-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rohleder N., Aringer M., Boentert M. Role of interleukin-6 in stress, sleep, and fatigue. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2012;1261:88–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2012.06634.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fleming K.C., Volcheck M.M. Central sensitization syndrome and the initial evaluation of a patient with fibromyalgia: a review. Rambam Maimonides Med J. 2015;6(2) doi: 10.5041/RMMJ.10204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fujii H., Sato W., Kimura Y., et al. Altered structural brain networks related to adrenergic/muscarinic receptor autoantibodies in chronic fatigue syndrome. J Neuroimaging. 2020;30(6):822–827. doi: 10.1111/jon.12751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Maksoud R., du Preez S., Eaton-Fitch N., et al. A systematic review of neurological impairments in myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome using neuroimaging techniques. PLoS One. 2020;15(4) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0232475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tirelli U., Chierichetti F., Tavio M., et al. Brain positron emission tomography (PET) in chronic fatigue syndrome: preliminary data. Am J Med. 1998;105(3A):54S–58S. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(98)00179-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Diers M., Schley M.T., Rance M., et al. Differential central pain processing following repetitive intramuscular proton/prostaglandin E2 injections in female fibromyalgia patients and healthy controls. Eur J Pain. 2011;15(7):716–723. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2010.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Arnold L.M., Fan J., Russell I.J., et al. The fibromyalgia family study: a genome-wide linkage scan study. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65(4):1122–1128. doi: 10.1002/art.37842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.D'Agnelli S., Arendt-Nielsen L., Gerra M.C., et al. Fibromyalgia: genetics and epigenetics insights may provide the basis for the development of diagnostic biomarkers. Mol Pain. 2019;15 doi: 10.1177/1744806918819944. 1744806918819944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Fernandez-de-Las-Penas C., Ambite-Quesada S., Gil-Crujera A., Cigaran-Mendez M., Penacoba-Puente C. Catechol-O-methyltransferase Val158Met polymorphism influences anxiety, depression, and disability, but not pressure pain sensitivity, in women with fibromyalgia syndrome. J Pain. 2012;13(11):1068–1074. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2012.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.