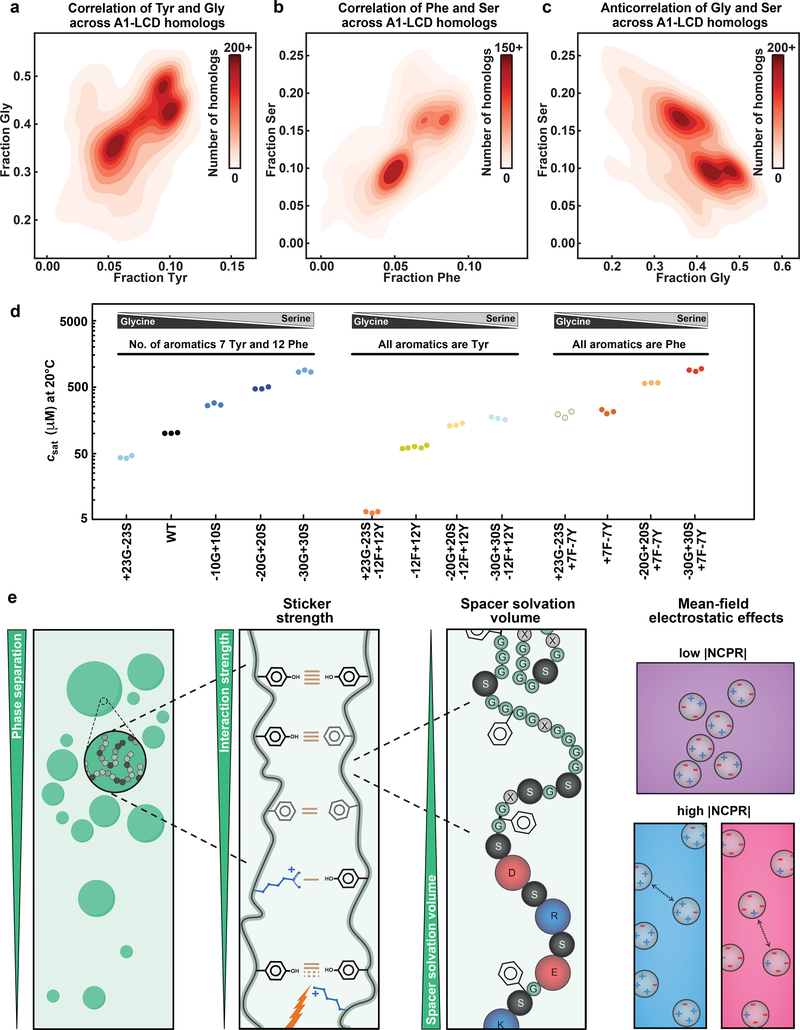

Fig. 7: Gly and Ser are spacers with different effective solvation volume.

(a-c) 2D histograms quantifying covariations in fractions of Tyr versus Gly (a), Phe versus Ser (b), and Ser versus Gly (c) residues across A1-LCD homologs. (d) A1-LCD variant saturation concentrations measured at 20°C. Gly vs. Ser content is titrated in the WT A1-LCD (left), in the background of the variant in which all aromatic residues are Tyr (middle), or in the background of the variant in which all aromatic residues are Phe (right). (e) Cartoon highlighting the hierarchy of physicochemical effects underlying the driving force of phase separation encoded in the evolutionarily conserved composition of PLCDs. Cohesive interactions between disordered chains made up of sticker and spacer residues (beads of grey shades) result in condensates (green droplets). Tyr-Tyr, Tyr-Phe and Phe-Phe interactions have, in order, decreasing pairwise interaction strengths. Arg residues act as auxiliary stickers with aromatic residues if the NCPR is favorable. Lys residues weaken sticker-sticker interactions via 3-body effects. Glycine, serine and charged residues are spacer residues that modulate the driving forces for phase separation through their effects on the ves of spacers. The higher the ves, the weaker is the driving force for phase separation. The NCPR of PLCDs affects phase separation via mean-field electrostatic effects, modulating the saturation concentration by up to three orders of magnitude. NCPR values close to electroneutrality favor phase separation whereas unbalanced charges increase solubility and weaken phase separation.