Abstract

Background

The effective reproduction number, Rt, is a tool to track and understand pandemic dynamics. This investigation of Rt estimations was conducted to guide the national COVID-19 response in Qatar, from the onset of the pandemic until August 18, 2021.

Methods

Real-time “empirical” RtEmpirical was estimated using five methods, including the Robert Koch Institute, Cislaghi, Systrom-Bettencourt and Ribeiro, Wallinga and Teunis, and Cori et al. methods. Rt was also estimated using a transmission dynamics model (RtModel-based). Uncertainty and sensitivity analyses were conducted. Correlations between different Rt estimates were assessed by calculating correlation coefficients, and agreements between these estimates were assessed through Bland-Altman plots.

Results

RtEmpirical captured the evolution of the pandemic through three waves, public health response landmarks, effects of major social events, transient fluctuations coinciding with significant clusters of infection, and introduction and expansion of the Alpha (B.1.1.7) variant. The various estimation methods produced consistent and overall comparable RtEmpirical estimates with generally large correlation coefficients. The Wallinga and Teunis method was the fastest at detecting changes in pandemic dynamics. RtEmpirical estimates were consistent whether using time series of symptomatic PCR-confirmed cases, all PCR-confirmed cases, acute-care hospital admissions, or ICU-care hospital admissions, to proxy trends in true infection incidence. RtModel-based correlated strongly with RtEmpirical and provided an average RtEmpirical.

Conclusions

Rt estimations were robust and generated consistent results regardless of the data source or the method of estimation. Findings affirmed an influential role for Rt estimations in guiding national responses to the COVID-19 pandemic, even in resource-limited settings.

The severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) pandemic is the most serious global health challenge in recent history [1,2]. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) morbidity and mortality has imposed unparalleled burdens on health care systems worldwide, and necessitated unprecedented restrictions on mobility and on social and economic activities [3,4]. Tracking and monitoring each wave of infection have become essential to avoid the adverse consequences of infection transmission [5-8]. With such serious consequences to the health care system, economy, and society, decisions regarding the escalation or easing of restrictions have become a critical facet of policymaking since the discovery of the virus in December of 2019 [6,9,10].

The effective reproduction number (Rt), the average number of secondary infections each infection is generating at a given point in time [6,11-13], has been shown to be an influential tool in monitoring and tracking the epidemic, and informing the escalation and easing of public health restrictions [6,11-13]. The basic underlying hypothesis of the present study, through its application for Qatar, is that Rt offers an effective method to capture epidemic dynamics during an evolving epidemic, and helps establishing national policy decisions and public heath interventions. In essence, we report here on what has become a successful country experience.

Qatar is a peninsula in the Arabian Gulf with a diverse population of 2.8 million people [5,14] that has been affected by three SARS-CoV-2 pandemic waves [5,6,15-20]. The first wave started with the introduction of the virus in February of 2020 and peaked in late May 2020 [5,6]. The second wave started in mid-January, 2021, and was triggered by the introduction and expansion of the Alpha [21] (B.1.1.7) variant [15-19,22]. This wave peaked in the first week of March, but was followed immediately by a third wave that was triggered by introduction and rapid expansion of the Beta [21] (B.1.351) variant, which started in mid-March and peaked in mid-April, 2021 [15-19,22].

The overarching aim of the present article was to describe the two forms of Rt estimation that have been used in Qatar to inform the national COVID-19 response. Each proved to have its own intrinsic public health value. The first is the real-time “empirical” estimation which is done by calculating Rt directly from diagnosed cases. Different methods were explored for estimating the empirical Rt (henceforth, RtEmpirical), and based on this exploration the Robert Koch Institute method [13,23] was used for feasibility, ease of use, and functionality in consideration of the kind of data available in Qatar. The second estimation method was model-based by calculating RtE using a population-level compartmental transmission dynamics model [6,24], hereafter designated as RtModel-based.

METHODS

Data sources

Mathematical modeling analyses were conducted using the centralized, integrated, and standardized national SARS-CoV-2 databases compiled at Hamad Medical Corporation (HMC), the main public health care provider and the nationally designated provider for all COVID-19 health care needs. These databases have captured all SARS-CoV-2-related data since the start of the pandemic, including all records of polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing, antibody testing, COVID-19 hospitalizations, vaccinations, infection severity classification per World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines [25], and COVID-19 deaths, also assessed per WHO guidelines [26].

Every PCR test conducted in Qatar, regardless of location (outpatient clinic, drive-through, or hospital, etc.), is classified on the basis of symptoms and the reason for testing (clinical symptoms, contact tracing, random testing campaigns, individual requests, health care routine testing, pre-travel, and at port of entry). PCR-confirmed infections are classified as “symptomatic” if testing was done because of clinical suspicion due to symptoms compatible with a respiratory tract infection.

Classification of infections by variant type was informed by weekly rounds of viral genome sequencing and multiplex, real-time reverse-transcription PCR (RT-qPCR) variant screening [27] of randomly collected clinical samples [15-19], as well as by results of deep sequencing of wastewater samples [17]. Based on existing evidence [28-30] and confirmation with viral genome sequencing [22], an Alpha case was defined as an S-gene “target failure” using the TaqPath COVID-19 Combo Kits (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) [31]. This method accounted for >85% of PCR testing in Qatar, applying the criterion of a PCR cycle threshold (Ct) value ≤30 for both the N and ORF1ab genes, and a negative outcome for the S gene [30]. This definition was used to derive the Alpha case series data that were used subsequently to derive RtEmpirical for only the Alpha variant.

Empirical estimation methods

Five methods [13,32] of common use in the literature and in public health practice were investigated and compared for calculating RtEmpirical from daily diagnosed cases. To minimize effects of bias due to variation in the PCR testing volume over time, RtEmpirical was calculated using only the time series of cases diagnosed due to presence of clinical symptoms. Cases diagnosed through testing conducted for other reasons were not used in these analyses, except in a sensitivity analysis.

Robert Koch Institute method

This method, which was chosen as the standard method for RtEmpirical estimation in Qatar, utilizes the generation time (τG), the time interval between the infection of an infector and an infectee in a transmission pair [13,23], to provide an estimate for RtEmpirical. RtEmpirical is calculated as the sum of newly diagnosed cases during τG consecutive days over the sum of previously diagnosed cases during the τG preceding days [23]. τG was assumed to be seven days, as informed by empirical evidence [33,34]. To smooth the curve and to avoid strong daily variations due to noise, RtEmpirical was calculated as a three-day moving average.

The range of uncertainty in the estimated RtEmpirical due to sampling variation was derived by applying the binomial sampling distribution to the number of positive PCR tests out of all tests, day by day, and repeating this process 1000 times.

Four sensitivity analyses on the estimated RtEmpirical were conducted. In the first sensitivity analysis, the time series of all diagnosed cases (regardless of reason for PCR testing) was used instead of the time series of only symptomatic cases. In the second and third sensitivity analyses, the time series of hospital admissions in acute-care beds and ICU-care beds was used to proxy the pandemic trend, instead of the time series of symptomatic cases. In the fourth sensitivity analysis, the generation time τG was assumed to be 5, 7, and 10 days, instead of the fixed value of seven days [33,34].

Cislaghi method

This method utilizes the incubation time (τI), the time interval between infection and symptom onset in an infected individual [34], to generate an estimate for RtEmpirical. RtEmpirical is calculated as the number of newly diagnosed cases on day s over the number of newly diagnosed cases on day s – τI [35]. τI was assumed to be five days [33,34]. To smooth the curve and to avoid strong daily variations due to noise, RtEmpirical was calculated as a three-day moving average.

Wallinga and Teunis method

This method utilizes the serial interval (τS), the time interval between symptom onset of an infector and that of an infectee [34], to generate an estimate for RtEmpirical. A likelihood-based estimate for RtEmpirical is derived by using pairs of diagnosed cases and the probability distribution for τS [36]. τS was assumed to have a Weibull distribution with a mean of 5.19 days and a standard deviation of 1.39 days, as informed by a meta-analysis of available data for SARS-CoV-2 infection [37].

Systrom-Bettencourt and Ribeiro method

This method utilizes an approximate relationship between RtEmpirical and the exponential growth of the pandemic, and assumes that RtEmpirical evolves as a Gausian process to provide a Bayesian RtEmpirical estimation [12,38-40]. A Gaussian filter was applied to account for daily variations (noise) in RtEmpirical using a variance that was estimated by maximizing the log-likelihood of observing newly diagnosed cases [12,38-40].

Cori et al. method

This method utilizes the infectivity profile (ωS) of an infected individual to generate an estimate for RtEmpirical [32]. The average RtEmpirical is estimated by the ratio of the number of newly diagnosed cases at time step t, to the sum of newly diagnosed cases up to time step t – 1, weighted by ωS. The infectivity profile was approximated by the distribution of the serial interval [32]. Bayesian statistical inference based on a Poisson process was used to generate the posterior distribution of RtEmpirical, after assuming a gamma prior distribution for RtEmpirical [32].

Model-based estimation method

An age-structured deterministic mathematical model was developed to describe SARS-CoV-2 transmission dynamics in the population of Qatar [6,24]. The model was developed as informed by other models [6,24,41-43], and has been used, expanded, and continuously refined since the onset of the pandemic. This model has been the reference model for policy decision-making in Qatar, for providing forecasts, investigating epidemiology, and assessing the impact of public health interventions [6,24].

The model stratified the population into compartments according to age group (0-9, 10-19, 20-29, …, ≥80 years), infection status (infected, uninfected), infection type (asymptomatic/mild, severe, and critical), COVID-19 disease type (severe or critical disease), and vaccination status (vaccinated, unvaccinated) using sets of coupled, nonlinear differential equations (Figure S1 in the Online Supplementary Document).

The model was parameterized using current data for SARS-CoV-2 natural history and epidemiology [6,24]. It was fitted to the national standardized, integrated, and centralized databases of SARS-CoV-2 diagnosed cases, SARS-CoV-2 PCR and antibody testing, COVID-19 hospitalizations, and COVID-19 mortality [6], as well as to data of a series of SARS-CoV-2 epidemiological studies in Qatar [5,22,44-49]. The size and demographic structure of the population of Qatar were based on data from Qatar’s Planning and Statistics Authority [5,14,50].

RtModel-based was derived using this model and was expressed in terms of the social contact rate in the population, transmission probability of the infection per contact, duration of infectiousness, and proportion of the population that is still susceptible to the infection [6,24]. A detailed description of the model, its input data, and fitting are available in References [6,24]. The model was coded, fitted, and analyzed using MATLAB R2019a [51].

Correlations and agreements between Rt estimates

Correlations between different Rt estimates were assessed by calculating both the Pearson correlation coefficient, to assess the existence of a linear relationship, and also by calculating the Spearman correlation coefficient, to assess the existence of a monotonic (rank) relationship. Agreements between different Rt estimates were assessed through Bland-Altman plots.

Ethical approvals

This study was approved by the HMC and Weill Cornell Medicine-Qatar Institutional Review Boards.

RESULTS

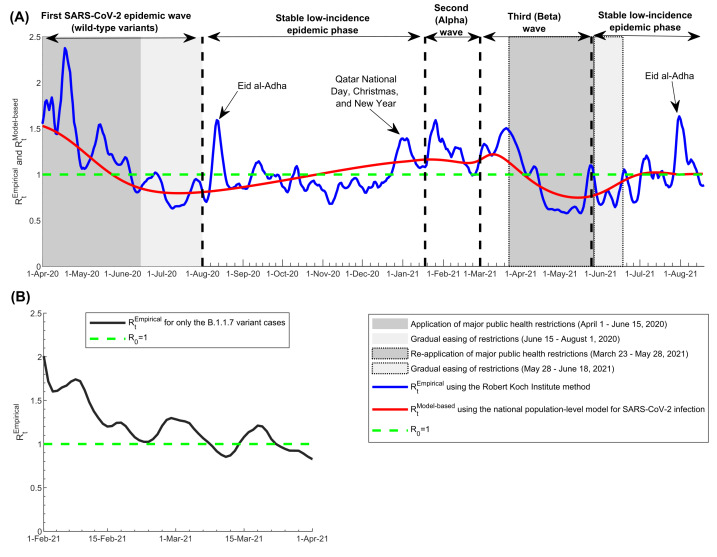

The RtEmpirical calculated using the Robert Koch Institute method captured effectively the evolution of the pandemic through its three waves, starting from the first wave (the wild-type variant wave) [5,6], the second (Alpha) wave [15-19,22], and the third (Beta) wave [15-19,22] (Figure 1, Panel A). It also captured and correlated with key response landmarks, such as partial lockdowns during the three waves and subsequent easing of public health restrictions, and major social events that led to transient increases in the social contact rate in the population. It further captured transient fluctuations that were associated with significant clusters of infection, especially during low-incidence phases between August 1, 2020 and January 17, 2021, and between May 25, 2021 and August 18, 2021.

Figure 1.

Effective reproduction numbers RtEmpirical and RtModel-based in Qatar. A) Trend in RtEmpirical and RtModel-based, April 1, 2020 to August 18, 2021, and association with major events, response landmarks, and introduction and expansion of the Alpha (B.1.1.7) and Beta (B.1.135) variants. B) Trend in RtEmpirical for only the Alpha variant cases, February 1, 2021 to April 1, 2021. RtEmpirical was estimated using the Robert Koch Institute method [23] applied to symptomatic case series data. The dashed green line represents the threshold of R0 = 1.

The pandemic expansion of Alpha cases starting from January 18, 2021 was associated with a large and rapid increase in RtEmpirical (Figure 1, Panel A), suggesting the higher infectiousness of this variant. RtEmpirical calculated using only Alpha case series data are shown in Figure 1, Panel B, and demonstrated higher values, confirming further the higher infectiousness of this variant. RtEmpirical for only the Alpha variant averaged 1.45 during the exponential growth phase of the second (Alpha) wave (February 1-22, 2021). It was unstable during the first two weeks of this wave (January 18-31, 2021; not shown), as transmission appears to have been influenced by one or more superspreading events that were not representative of the average community transmission. It was also unstable after April 1, 2021, as the number of daily Alpha cases was too small.

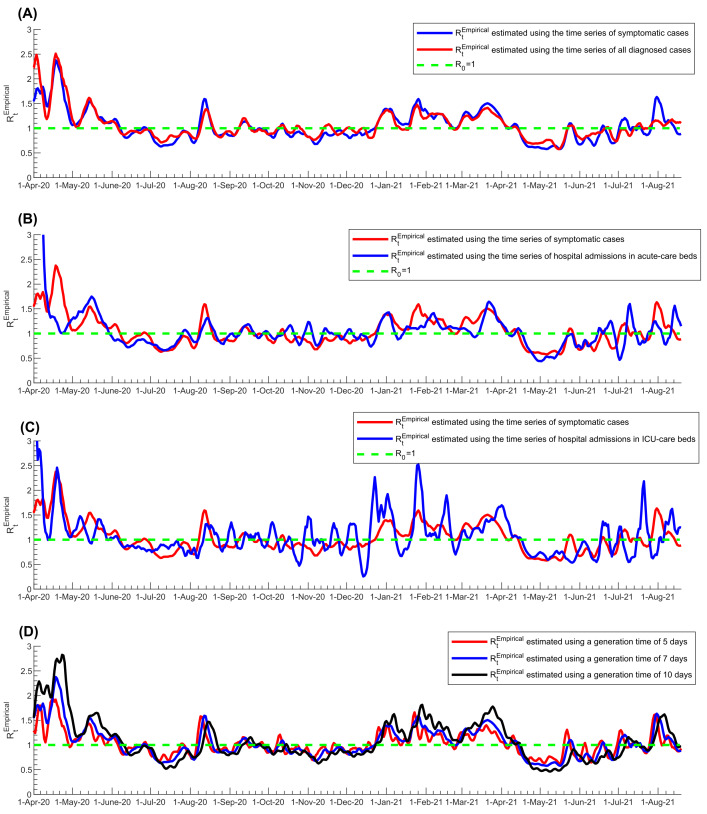

The first sensitivity analysis on the estimated RtEmpirical, in which the time series of all diagnosed cases was used instead of only symptomatic cases, showed overall excellent correlation, negligible bias, and narrow limits of agreement regardless of the input-data source used to calculate RtEmpirical (Figure 2, Panel A. and Figure S2A in the Online Supplementary Document). The Pearson correlation coefficient was 0.914 (P < 0.001) and the Spearman correlation coefficient was 0.913 (P < 0.001), both confirming the excellent correlation. There were only few noticeable differences that occurred when the number of diagnosed cases was too small (periods when SARS-CoV-2 incidence was low); thus, RtEmpirical was more susceptible to transient variation in the number of diagnosed cases, such as due to sporadic, random PCR testing campaigns. Peaks in RtEmpirical were also slightly larger using only symptomatic cases vs all diagnosed cases.

Figure 2.

Sensitivity analyses of estimated RtEmpirical using the Robert Koch Institute method. A) Sensitivity analysis using the time series of all diagnosed cases instead of only symptomatic cases in estimating RtEmpirical. B) Sensitivity analysis using the time series of hospital admissions in acute-care beds instead of symptomatic cases in estimating RtEmpirical. C) Sensitivity analysis using the time series of hospital admissions in ICU-care beds instead of symptomatic cases in estimating RtEmpirical. D) Sensitivity analysis using different values for the generation time in estimating RtEmpirical. The dashed green line represents the threshold of R0 = 1.

The second sensitivity analysis, in which the time series of acute-care hospital admissions was used to proxy the pandemic trend, instead of the time series of symptomatic cases, showed rather strong correlation, negligible bias, and adequate limits of agreement between RtEmpirical estimates (Figure 2, Panel B, and Figure S2B in the Online Supplementary Document). The Pearson correlation coefficient was 0.512 (P < 0.001) and the Spearman correlation coefficient was 0.716 (P < 0.001), both confirming strong correlation. The third sensitivity analysis, in which the time series of ICU-care hospital admissions was used to proxy the pandemic trend, instead of the time series of symptomatic cases, also showed rather strong correlation, negligible bias, and adequate limits of agreement between the RtEmpirical estimates, but also large fluctuations in RtEmpirical (Figure 2, Panel C, and Figure S2C in the Online Supplementary Document). The Pearson correlation coefficient was 0.589 (P < 0.001) and the Spearman correlation coefficient was 0.550 (P < 0.001), both confirming strong correlation, but rather inferior to that for acute-care hospital admissions (Figure 2, Panel B vs Panel C).

The fourth sensitivity analysis, in which different values for the generation time τG were used, showed also excellent correlation, negligible bias, and adequate limits of agreement between different RtEmpirical estimates (Figure 2, Panel D, and Figure S2D in the Online Supplementary Document). The Pearson correlation coefficient was 0.901 (P < 0.001) and the Spearman correlation coefficient was 0.900 (P < 0.001), both confirming excellent correlation. The main differences between the estimates occurred in the timing and magnitude of peaks of the pandemic waves, as expected, since variation in generation time changes the rate of pandemic growth [52]. The differences were larger at higher RtEmpirical values (Figure S2D in the Online Supplementary Document).

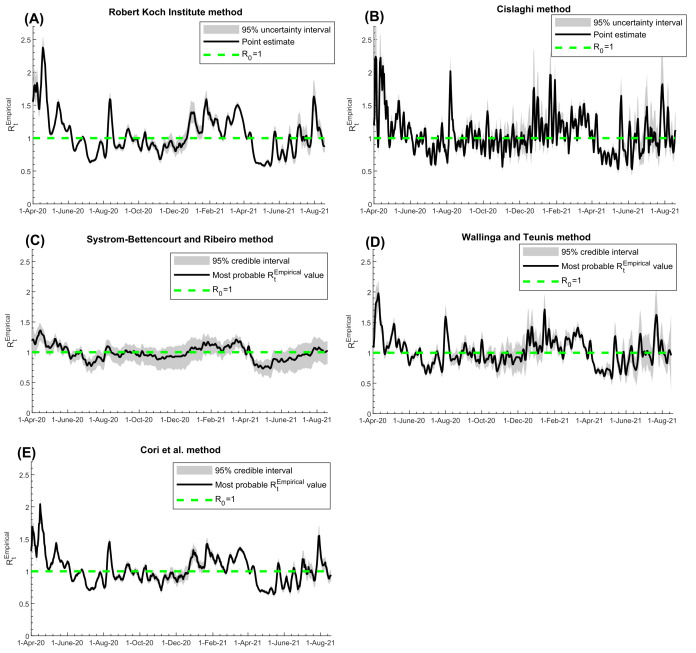

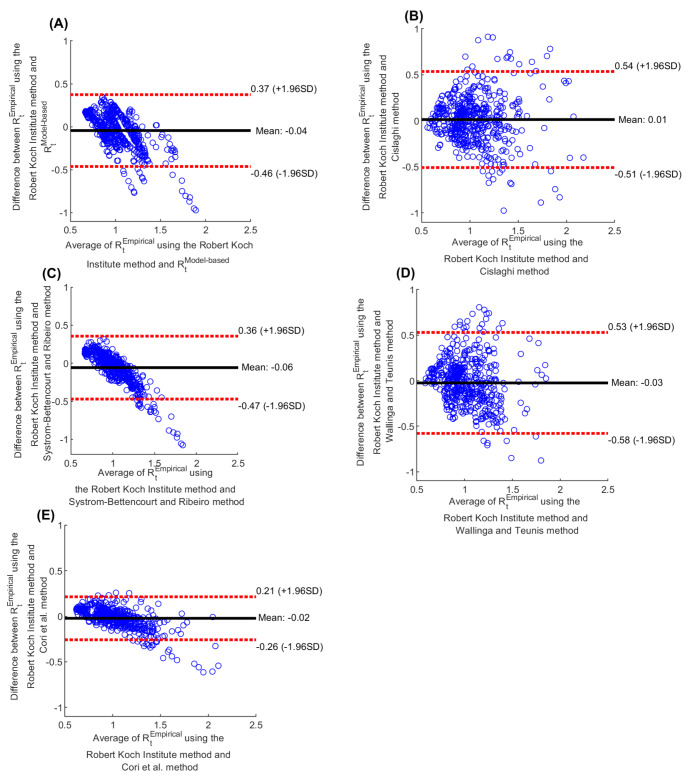

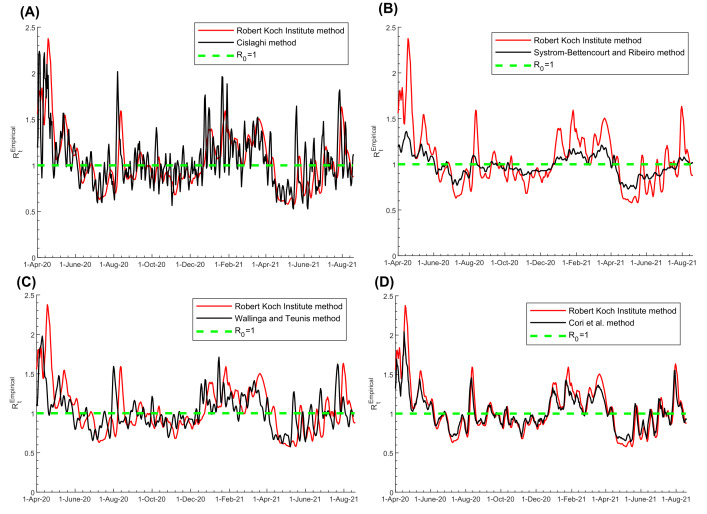

RtEmpirical estimated using the Robert Koch Institute method (Figure 3, Panel A), Cislaghi method (Figure 3, Panel B), Systrom-Bettencourt and Ribeiro method (Figure 3, Panel C), Wallinga and Teunis method (Figure 3, Panel D), and Cori et al. method (Figure 3, Panel E), all showed similar results and were able to capture the evolution of pandemic waves and transient variations due to national public-health response landmarks and major social events. There were also overall strong correlations between them (Table 1). Bland-Altman plots showed overall negligible bias and narrow or adequate limits of agreement between RtEmpirical estimated using the Robert Koch Institute method and each of the other methods (Figure 4). However, the Systrom-Bettencourt and Ribeiro method (Figure 3, Panel C) tended to provide something of an average RtEmpirical and was not as sensitive to transient changes in RtEmpirical (Figure 3 and Figure 5).

Figure 3.

Trend in RtEmpirical in Qatar, April 1, 2020 to August 18, 2021, using the A) Robert Koch Institute method [23], B) Cislaghi method [35], C) Systrom-Bettencourt and Ribeiro method [12,38-40], D) Wallinga and Teunis method [36], and E) Cori et al. method [32]. The figure includes the 95% uncertainty or credible interval, as applicable for each method. The dashed green line represents the threshold of R0 = 1.

Table 1.

Correlations between RtModel-based and RtEmpirical using the A) Robert Koch Institute method [23], B) Cislaghi method [35], C) Systrom-Bettencourt and Ribeiro method [12,38-40], D) Wallinga and Teunis method [36], and E) Cori et al. method [32]

| RtModel-based | RtEmpirical, Robert Koch Institute method | RtEmpirical, Cislaghi method | RtEmpirical, Systrom-Bettencourt and Ribeiro method | RtEmpirical, Wallinga and Teunis method | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Pearson correlation coefficient:

| |||||

|

RtEmpirical, Robert Koch Institute method

|

0.731 (P < 0.001) |

|

|

|

|

|

RtEmpirical, Cislaghi method

|

0.567 (P < 0.001) |

0.605 (P < 0.001) |

|

|

|

|

RtEmpirical, Systrom-Bettencourt and Ribeiro method

|

0.785 (P < 0.001) |

0.852 (P < 0.001) |

0.718 (P < 0.001) |

|

|

|

RtEmpirical, Wallinga and Teunis method

|

0.648 (P < 0.001) |

0.471 (P < 0.001) |

0.446 (P < 0.001) |

0.589 (P < 0.001) |

|

|

RtEmpirical, Cori et al. method

|

0.718 (P < 0.001) |

0.943 (P < 0.001) |

0.760 (P < 0.001) |

0.886 (P < 0.001) |

0.469 (P < 0.001) |

|

Spearman correlation coefficient:

| |||||

|

RtEmpirical, Robert Koch Institute method

|

0.684 (P < 0.001) |

|

|

|

|

|

RtEmpirical, Cislaghi method

|

0.540 (P < 0.001) |

0.597 (P < 0.001) |

|

|

|

|

RtEmpirical, Systrom-Bettencourt and Ribeiro method

|

0.749 (P < 0.001) |

0.853 (P < 0.001) |

0.718 (P < 0.001) |

|

|

|

RtEmpirical, Wallinga and Teunis method

|

0.635 (P < 0.001) |

0.492 (P < 0.001) |

0.421 (P < 0.001) |

0.608 (P < 0.001) |

|

| RtEmpirical, Cori et al. method | 0.677 (P < 0.001) | 0.946 (P < 0.001) | 0.745 (P < 0.001) | 0.880 (P < 0.001) | 0.473 (P < 0.001) |

Figure 4.

Bland-Altman plots for agreement between different methods for estimating Rt. A) Bland-Altman comparison between RtEmpirical estimated using the Robert Koch Institute method [23] and RtModel-based. Bland-Altman comparison between RtEmpirical estimated using the Robert Koch Institute method [23] and that estimated using the B) Cislaghi method [35], C) Systrom-Bettencourt and Ribeiro method [12,38-40], D) Wallinga and Teunis method [36], and E) Cori et al. method [32]. The black line is the mean difference (bias) and the dashed red lines show the 95% limits of agreement.

Figure 5.

Pairwise comparison between RtEmpirical estimated using the Robert Koch Institute method [23] and that estimated using the A) Cislaghi method [35], B) Systrom-Bettencourt and Ribeiro method [12,38-40], C) Wallinga and Teunis method [36], and D) Cori et al. method [32]. The dashed green line represents the threshold of R0 = 1.

There were differences in how rapidly each method detected a change in pandemic dynamics (Figure 5). The Wallinga and Teunis method was the fastest at detecting a change, while the Robert Koch Institute method was the slowest, leading to weaker Pearson and Spearman correlation coefficients between them (Table 1). For instance, the surge in RtEmpirical during the first Eid al-Adha after pandemic onset (a festival that occurred between July 30 and August 6, 2020 and is associated with celebrations and social gatherings) was detected on August 1, August 7, August 8, August 11, and August 13 using the Wallinga and Teunis, Cislaghi, Systrom-Bettencourt and Ribeiro, Cori et al., and Robert Koch Institute methods, respectively.

Uncertainty intervals around the RtEmpirical estimates of the various methods were narrow overall, except when the number of diagnosed symptomatic cases or the number of PCR tests was small, specifically during the low-incidence phases of the pandemic (Figure 3). Overall, the uncertainty in RtEmpirical estimates did not impact the interpretation of the RtEmpirical results (Figure 3). The only exception was for the Systrom-Bettencourt and Ribeiro method, as it showed rather wide uncertainty intervals compared to the point estimates for RtEmpirical (Figure 3, Panel C).

The RtModel-based correlated strongly with the RtEmpirical using different methods (Table 1), and provided somewhat of an average of the RtEmpirical (Figure 1). For example, RtModel-based and RtEmpirical averaged 1.15 and 1.14 during the first wave, respectively. While it captured the three pandemic waves, it could not capture the transient fluctuations in RtEmpirical nor the effects of significant clusters during low-incidence phases.

DISCUSSION

RtEmpirical and RtModel-based estimated in Qatar proved useful in real-time tracking of pandemic trends, understanding pandemic dynamics, and setting interventions to control transmission, such as application or easing of public health restrictions. Both forms were integral to the national public health response and to formulating evidence-based policy decisions to minimize the pandemic’s toll on health, society, and the economy throughout the phases of this pandemic.

RtEmpirical effectively captured the evolution of the pandemic during its three waves, the effects of the response landmarks, such as the partial lockdowns and easing of public health restrictions, and the major social events that affected the social contact rate in the population. Even transient fluctuations in infection transmission that occurred because of significant infection clusters were captured by RtEmpirical. Strikingly, the introduction and expansion of the Alpha variant [22], that resulted in the second pandemic wave, was discovered immediately through RtEmpirical monitoring, as there was a sudden large, sustained increase in Rt that coincided precisely with a rapidly increasing number of S-gene “target failures” in PCR testing, even before viral genome sequencing was conducted to confirm the presence and expansion of this variant in the population [18].

While RtModel-based provided an average Rt that closely tracked the average RtEmpirical, it did not have the resolution to capture transient changes in RtEmpirical other than major changes associated with the three pandemic waves. Still, RtEmpirical was useful and influential, as it was, along with the model that generated it [6,24], the basis for forecasting and future planning, such as forecasting the pandemic time-course and pandemic potential, forecasting health care needs of acute-care and ICU-care bed hospitalizations, predicting the impact of social and physical distancing restrictions, planning for easing of restrictions, and forecasting the impact of different mass vaccination strategies [6,24]. Therefore, both forms of RtEmpirical complement each other and should be part of any effective COVID-19 national response.

RtEmpirical estimation proved robust in sensitivity analyses conducted to assess its utility. Baseline estimation of RtEmpirical was based on the time series of symptomatic cases as a proxy of the actual incidence of SARS-CoV-2 infection in the population, which is unknown. Using the time series of all diagnosed cases instead of just symptomatic cases did not appreciably impact RtEmpirical estimation, even though PCR testing volume and strategies varied throughout the pandemic. Using the time series of acute-care hospital admissions instead of the time series of symptomatic cases also led to comparable estimates for RtEmpirical This was also the case, but with weaker correlation, when the time series of ICU-care hospital admissions was used to proxy trends in infection incidence. This is not surprising as there is a long delay between onset of infection and ICU-care hospital admission, and the number of ICU-care admissions was relatively small with the low COVID-19 severity in Qatar’s predominantly young and working-age population [5,49]. Variations in the assumed value for the generation time in the RtEmpirical estimation did not heavily impact estimates. These findings support the robustness of the approach employed to estimate RtEmpirical.

Examination of different methods to estimate RtEmpirical demonstrated consistency of the results, generally strong correlations between the estimates, and an acceptable level of uncertainty in them. The only exception was the Systrom-Bettencourt and Ribeiro method which tended to provide something of an average RtEmpirical. It was not as sensitive to transient changes in RtEmpirical, and had wide uncertainty intervals compared to the point estimates. There were also differences in how rapidly each method detected a change in pandemic dynamics. The Wallinga and Teunis method was the fastest to detect a change, while the Robert Koch Institute method was the slowest. Yet, overall, these findings support the robustness of using these methods in RtEmpirical estimation and to guide COVID-19 national responses.

This study has limitations. The estimated RtEmpirical and RtModel-based are contingent on the validity and generalizability of input data. There were not sufficient data on infection seroprevalence and seroincidence to refine the model used to generate RtModel-based. However, the model was fitted to the standardized and centralized national databases of SARS-CoV-2 PCR and antibody testing, documented infections, hospitalizations, mortality, and vaccinations in Qatar. The uncertainty/credible intervals estimated here accounted for the uncertainty arising from sampling variation, or from our imperfect knowledge of specific epidemiological quantities, such as the serial interval, but did not account for other sources of uncertainty, such as our imperfect knowledge of the true incidence of infection in the population. To reduce bias due to variation in volume and strategies of PCR testing over time, RtEmpirical was calculated using the time series of symptomatic cases, but the distribution of the delay between onset of infection and onset of symptoms may bias these estimates. RtModel-based was estimated using a deterministic compartmental model, but this type of model may not be representative of stochastic transmission dynamics, particularly when the number of infections is small. Despite these limitations, RtEmpirical and RtModel-based were able to capture the evolution of the pandemic through its several waves, and to effectively inform the national response and policy decision-making.

CONCLUSIONS

Rt estimations played a critical and influential role in the COVID-19 national response in Qatar. RtEmpirical effectively captured the evolution of the pandemic during its three waves in Qatar, and proved useful in understanding pandemic dynamics and setting interventions to control transmission. Even though surveillance data of SARS-CoV-2 infection are imperfect and prone to bias, Rt estimations were robust and generated consistent results regardless of the data source used, or the method employed in generating estimates. These findings affirm the value and complementarity of using both RtEmpirical and RtModel-based to track the pandemic in real-time and to inform public health decision making at a national level across countries. This can also be done despite low-resource demands, as Rtl estimation utilizes existing surveillance data. Moreover, application of some of the estimation methods is feasible even without established expertise in infectious disease modeling. Since the choice of estimation method does not impact the estimates, each country may decide on the best approach, method, and source of data to be used in the estimation, weighing feasibility, ease of use, and functionality, given its specific circumstances.

Additional material

Footnotes

Funding: HHA and RB acknowledge the joint support of Qatar University and Marubeni M-QJRC-2020-5. The authors are grateful for support provided by the Biomedical Research Program and the Biostatistics, Epidemiology, and Biomathematics Research Core, both at Weill Cornell Medicine-Qatar, as well as for support provided by the Ministry of Public Health and Hamad Medical Corporation. The developed mathematical models were made possible by NPRP grant number 9-040-3-008 (Principal investigator: LJA) and NPRP grant number 12S-0216-190094 (Principal investigator: LJA) from the Qatar National Research Fund (a member of Qatar Foundation; https://www.qnrf.org). The authors are also grateful for the Qatar Genome Programme for institutional support for the reagents needed for the viral genome sequencing. The statements made herein are solely the responsibility of the authors. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Authorship contributions: RB and HHA constructed, coded, and parameterized the mathematical models, and conducted the analyses. HC conducted statistical analyses. HHA and LJA conceived and led the design of the study, construct and parameterization of the mathematical models, and wrote the first draft of the article. All authors contributed to discussion and interpretation of the results and to the writing of the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests: Dr Butt has received institutional grant funding from Gilead Sciences unrelated to the work presented in this paper. The authors have completed the ICMJE Declaration of Interest Form (available upon request from the corresponding author), and declare no further conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.COVID-19 Outbreak Live Update Available from: https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/. Accessed on March 27, 2020. 2020.

- 2.United Nations. Shared responsibility, global solidarity: Responding to the socio-economic impacts of COVID-19. 2020. Available: https://www.un.org/sites/un2.un.org/files/sg_report_socio-economic_impact_of_covid19.pdf. Accessed on: 16 April 2020.

- 3.Kaplan J, Frias L, McFall-Johnsen M. A third of the global population is on coronavirus lockdown. Available from: https://www.businessinsider.com.au/countries-on-lockdown-coronavirus-italy-2020-3 Accessd on: April 25, 2020. Business Insider Australia. 2020.

- 4.Gilardino RE.Does “flattening the curve” affect critical care services delivery for COVID-19? A global health perspective. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2020;9:503-7. 10.34172/ijhpm.2020.117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abu-Raddad LJ, Chemaitelly H, Ayoub HH, Al Kanaani Z, Al Khal A, Al Kuwari E, et al. Characterizing the Qatar advanced-phase SARS-CoV-2 epidemic. Sci Rep. 2021;11:6233. 10.1038/s41598-021-85428-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ayoub HH, Chemaitelly H, Seedat S, Makhoul M, Al Kanaani Z, Al Khal A, et al. Mathematical modeling of the SARS-CoV-2 epidemic in Qatar and its impact on the national response to COVID-19. J Glob Health. 2021;11:05005. 10.7189/jogh.11.05005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kretzschmar ME, Rozhnova G, Bootsma MC, van Boven M, van de Wijgert JH, Bonten MJ.Impact of delays on effectiveness of contact tracing strategies for COVID-19: a modelling study. Lancet Public Health. 2020;5:e452-9. 10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30157-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hozé N, Paireau J, Lapidus N, Tran Kiem C, Salje H, Severi G, et al. Monitoring the proportion of the population infected by SARS-CoV-2 using age-stratified hospitalisation and serological data: a modelling study. Lancet Public Health. 2021;6:e408-15. 10.1016/S2468-2667(21)00064-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reiner RC, Barber RM, Collins JK, Zheng P, Adolph C, Albright J, et al. Modeling COVID-19 scenarios for the United States. Nat Med. 2021;27:94-105. 10.1038/s41591-020-1132-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abueg M, Hinch R, Wu N, Liu L, Probert W, Wu A, et al. Modeling the effect of exposure notification and non-pharmaceutical interventions on COVID-19 transmission in Washington state. NPJ Digit Med. 2021;4:49. 10.1038/s41746-021-00422-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Khailaie S, Mitra T, Bandyopadhyay A, Schips M, Mascheroni P, Vanella P, et al. Development of the reproduction number from coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 case data in Germany and implications for political measures. BMC Med. 2021;19:32. 10.1186/s12916-020-01884-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gostic KM, McGough L, Baskerville EB, Abbott S, Joshi K, Tedijanto C, et al. Practical considerations for measuring the effective reproductive number, Rt. PLOS Comput Biol. 2020;16:e1008409. 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1008409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Annunziato A, Asikainen T. Effective Reproduction Number Estimation from Data Series, EUR 30300 EN, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg, 2020, ISBN 978-92-76-20749-8, 10.2760/036156. 10.2760/036156 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Planning and Statistics Authority-State of Qatar. Qatar Monthly Statistics. Available from: https://www.psa.gov.qa/en/pages/default.aspx. Accessed on: May 26, 2020. 2020.

- 15.Abu-Raddad LJ, Chemaitelly H, Butt AA, National Study Group for Covid-19 Vaccination Effectiveness of the BNT162b2 Covid-19 Vaccine against the B.1.1.7 and B.1.351 Variants. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:187-9. 10.1056/NEJMc2104974 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chemaitelly H, Yassine HM, Benslimane FM, Al Khatib HA, Tang P, Hasan MR, et al. mRNA-1273 COVID-19 vaccine effectiveness against the B.1.1.7 and B.1.351 variants and severe COVID-19 disease in Qatar. Nat Med. 2021;27:1614-21. 10.1038/s41591-021-01446-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.National Project of Surveillance for Variants of Concern and Viral Genome Sequencing. Qatar viral genome sequencing data. Data on randomly collected samples. 2021. Available: https://www.gisaid.org/phylodynamics/global/nextstrain/. Accessed: 15 October 2021.

- 18.Benslimane FM, Al Khatib HA, Al-Jamal O, Albatesh D, Boughattas S, Ahmed AA, et al. One year of SARS-CoV-2: Genomic characterization of COVID-19 outbreak in Qatar. Front Cell Infect Microbiol.2021;11:768883. 10.3389/fcimb.2021.768883 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hasan MR, Kalikiri MKR, Mirza F, Sundararaju S, Sharma A, Xaba T, et al. Real-Time SARS-CoV-2 Genotyping by High-Throughput Multiplex PCR Reveals the Epidemiology of the Variants of Concern in Qatar. Int J Infect Dis. 2021;112:52-4. 10.1016/j.ijid.2021.09.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chemaitelly H, Tang P, Hasan MR, AlMukdad S, Yassine HM, Benslimane FM, et al. Waning of BNT162b2 Vaccine Protection against SARS-CoV-2 Infection in Qatar. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(24):e83. 10.1056/NEJMoa2114114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.World Health Organization. Tracking SARS-CoV-2 variants. Available from: https://www.who.int/en/activities/tracking-SARS-CoV-2-variants/. Accessed on: June 5, 2021. 2021.

- 22.Abu-Raddad LJ, Chemaitelly H, Ayoub HH, Coyle P, Malek JA, Ahmed AA, et al. Introduction and expansion of the SARS-CoV-2 B.1.1.7 variant and reinfections in Qatar: A nationally representative cohort study. PLoS Med. 2021;18:e1003879. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003879 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rober Koch Institut. Epidemiologisches Bulletin. 2020. Available: https://www.rki.de/DE/Content/Infekt/EpidBull/Archiv/2020/Ausgaben/17_20.pdf?__blob=publicationFile. Accessed: 28 May 2021.

- 24.Ayoub HH, Chemaitelly H, Makhoul M, Al Kanaani Z, Al Kuwari E, Butt AA, et al. Epidemiological impact of prioritising SARS-CoV-2 vaccination by antibody status: mathematical modelling analyses. BMJ Innovations. 2021;7:327. 10.1136/bmjinnov-2021-000677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.World Health Organization. COVID-19 clinical management: living guidance. 2021. Available: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-2019-nCoV-clinical-2021-1. Accessed: 15 May 2021.

- 26.World Health Organization. International guidelines for certification and classification (coding) of COVID-19 as cause of death. 2020. Available: https://www.who.int/classifications/icd/Guidelines_Cause_of_Death_COVID-19-20200420-EN.pdf?ua=1. Accessed: 15 May 2021.

- 27.Vogels C, Fauver J, Grubaugh N. Multiplexed RT-qPCR to screen for SARS-COV-2 B.1.1.7, B.1.351, and P.1 variants of concern V.3. 10.17504/protocols.io.br9vm966. 2021. Available: https://www.protocols.io/view/multiplexed-rt-qpcr-to-screen-for-sars-cov-2-b-1-1-br9vm966. Accessed: 15 October 2021. 10.17504/protocols.io.br9vm966 [DOI]

- 28.European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Rapid increase of a SARS-CoV-2 variant with multiple spike protein mutations observed in the United Kingdom. 2020. Available: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/SARS-CoV-2-variant-multiple-spike-protein-mutations-United-Kingdom.pdf. Accessed: 10 February 2021.

- 29.Galloway SE, Paul P, MacCannell DR, Johansson MA, Brooks JT, MacNeil A, et al. Emergence of SARS-CoV-2 B.1.1.7 Lineage - United States, December 29, 2020-January 12, 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70:95-9. 10.15585/mmwr.mm7003e2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Challen R, Brooks-Pollock E, Read JM, Dyson L, Tsaneva-Atanasova K, Danon L.Risk of mortality in patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 variant of concern 202012/1: matched cohort study. BMJ. 2021;372:n579. 10.1136/bmj.n579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thermo Fisher Scientific. TaqPath™ COVID-19 CE-IVD RT-PCR Kit instructions for use. 2020. Available: https://assets.thermofisher.com/TFS-Assets/LSG/manuals/MAN0019215_TaqPathCOVID-19_CE-IVD_RT-PCR%20Kit_IFU.pdf. Accessed: 2 December 2020.

- 32.Cori A, Ferguson NM, Fraser C, Cauchemez S.A New Framework and Software to Estimate Time-Varying Reproduction Numbers During Epidemics. Am J Epidemiol. 2013;178:1505-12. 10.1093/aje/kwt133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Deng Y, You C, Liu Y, Qin J, Zhou X-H.Estimation of incubation period and generation time based on observed length-biased epidemic cohort with censoring for COVID-19 outbreak in China. Biometrics. 2021;77:929-41. 10.1111/biom.13325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lehtinen S, Ashcroft P, Bonhoeffer S.On the relationship between serial interval, infectiousness profile and generation time. J R Soc Interface. 2021;18:20200756. 10.1098/rsif.2020.0756 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cislaghi C. Un cruscotto per monitorare l'evoluzione dell'epidemia. Scienzainrete. 2020 April 9, 2020.

- 36.Wallinga J, Teunis P.Different Epidemic Curves for Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Reveal Similar Impacts of Control Measures. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;160:509-16. 10.1093/aje/kwh255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rai B, Shukla A, Dwivedi LK.Estimates of serial interval for COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Epidemiol Glob Health. 2021;9:157-61. 10.1016/j.cegh.2020.08.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bettencourt LMA, Ribeiro RM.Real Time Bayesian Estimation of the Epidemic Potential of Emerging Infectious Diseases. PLoS One. 2008;3:e2185. 10.1371/journal.pone.0002185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Systrom K. The Metric We Need to Manage COVID-19. Systrom - Data, Machine Learning and Technology. 2020 April 12, 2020.

- 40.Systrom K. Estimating COVID-19's Rt in Real-Time. Realtime R0. United States of America: Github; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Makhoul M, Ayoub HH, Chemaitelly H, Seedat S, Mumtaz GR, Al-Omari S, et al. Epidemiological impact of SARS-CoV-2 vaccination: Mathematical modeling analyses. Vaccines (Basel). 2020;8:668. 10.3390/vaccines8040668 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ayoub HH, Chemaitelly H, Mumtaz GR, Seedat S, Awad SF, Makhoul M, et al. Characterizing key attributes of the epidemiology of COVID-19 in China: Model-based estimations. Glob Epidemiol. 2020;100042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ayoub HH, Chemaitelly H, Seedat S, Mumtaz GR, Makhoul M, Abu-Raddad LJ.Age could be driving variable SARS-CoV-2 epidemic trajectories worldwide. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0237959. 10.1371/journal.pone.0237959 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Al-Thani MH, Farag E, Bertollini R, Al Romaihi HE, Abdeen S, Abdelkarim A, et al. SARS-CoV-2 infection is at herd immunity in the majority segment of the population of Qatar. Open Forum Infectious Diseases. 2021;8:b221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Coyle PV, Chemaitelly H, Kacem M, Al Molawi NHA, El Kahlout RA, Gilliani I, et al. SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalence in the urban population of Qatar: An analysis of antibody testing on a sample of 112,941 individuals. iScience. 2021;24:102646. 10.1016/j.isci.2021.102646 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Abu-Raddad LJ, Chemaitelly H, Malek JA, Ahmed AA, Mohamoud YA, Younuskunju S, et al. Assessment of the risk of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) reinfection in an intense reexposure setting. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;73:e1830-e1830. 10.1101/2020.08.24.20179457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Abu-Raddad LJ, Chemaitelly H, Coyle P, Malek JA, Ahmed AA, Mohamoud YA, et al. SARS-CoV-2 antibody-positivity protects against reinfection for at least seven months with 95% efficacy. EClinicalMedicine. 2021;35:100861. 10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.100861 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jeremijenko A, Chemaitelly H, Ayoub HH, Alishaq M, Abou-Samra AB, Al Ajmi J, et al. Herd Immunity against Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 Infection in 10 Communities, Qatar. Emerg Infect Dis. 2021;27:1343-52. 10.3201/eid2705.204365 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Seedat S, Chemaitelly H, Ayoub HH, Makhoul M, Mumtaz GR, Al Kanaani Z, et al. SARS-CoV-2 infection hospitalization, severity, criticality, and fatality rates in Qatar. Sci Rep. 2021;11:18182. 10.1038/s41598-021-97606-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Planning and Statistics Authority-State of Qatar. The Simplified Census of Population, Housing & Establishments. 2019. Available: https://www.psa.gov.qa/en/statistics/Statistical%20Releases/Population/Population/2018/Population_social_1_2018_AE.pdf Accessed: 2 April 2020.

- 51.MATLAB®. The Language of Technical Computing. The MathWorks, Inc. 2019.

- 52.Anderson RM, May RM. Infectious diseases of humans: dynamics and control. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- Vogels C, Fauver J, Grubaugh N. Multiplexed RT-qPCR to screen for SARS-COV-2 B.1.1.7, B.1.351, and P.1 variants of concern V.3. 10.17504/protocols.io.br9vm966. 2021. Available: https://www.protocols.io/view/multiplexed-rt-qpcr-to-screen-for-sars-cov-2-b-1-1-br9vm966. Accessed: 15 October 2021. 10.17504/protocols.io.br9vm966 [DOI]