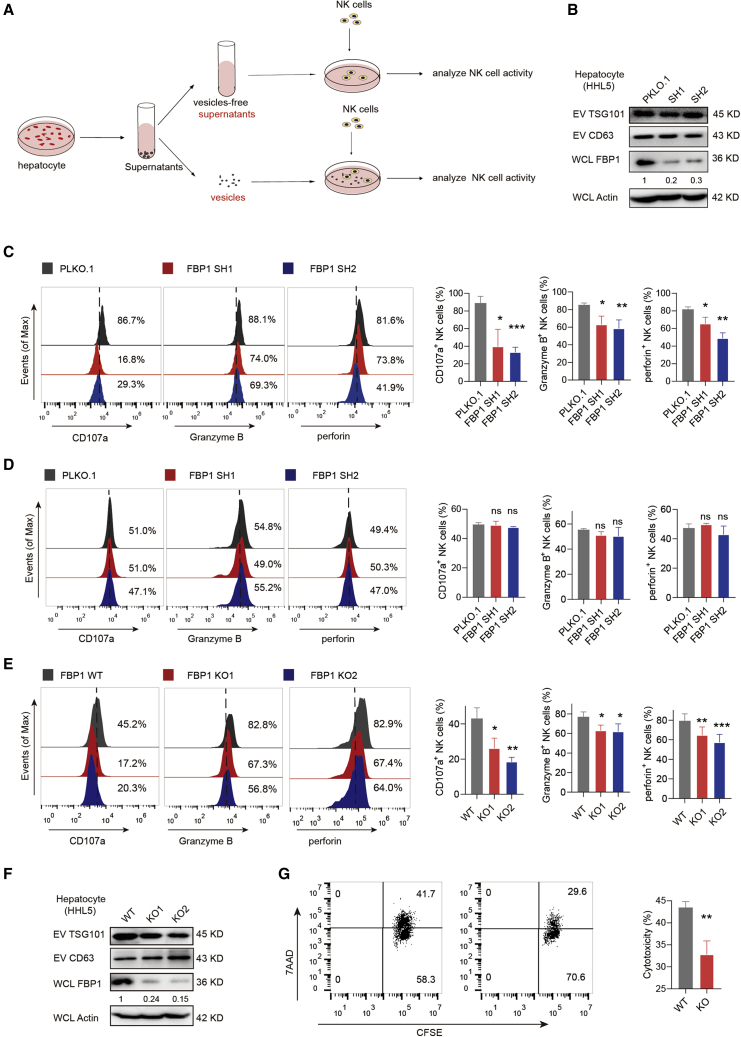

Figure 2.

EVs secreted by FBP1-deficient hepatocytes impair NK cell function

(A) Flowcharts illustrating the experimental design to examine the communication events between hepatocyte-derived EVs and NK cells. (B) Western blots confirming the knockdown efficiencies of FBP1 shRNAs. (C) Representative histograms (left) and quantifications (right) of indicated markers in NK cells incubated with equal amounts of EVs secreted from HHL5 cells with control PLKO.1 or FBP1 shRNAs. The quantification graphs display average relative frequencies of perforin+, CD107a+, or granzyme B+ NK cells. (D) Representative histograms (left) and quantifications (right) of indicated markers in NK cells incubated with equal amounts of vesicle-free supernatants from HHL5 cells with control PLKO.1 or FBP1 shRNAs. The quantification graphs display average relative frequencies of perforin+, CD107a+, or granzyme B+ NK cells. (E) Representative histograms (left) and quantifications (right) of indicated markers in NK cells incubated with equal amounts of EVs secreted from HHL5 cells with or without FBP1-targeting sgRNAs. (F) Western blots of TSG101 and CD63 expression in EVs secreted from FBP1-depleted HHL5 cells. (G) Cytotoxicity assay of primary NK cells incubated with EVs derived from hepatocytes with or without FBP1 against K562 target cells. The representative flow cytometry (FCM) profiles and quantifications of carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl amino ester+ 7-Aminoactinomycin D+ (CFSE+7AAD+) K562 cells were shown. Data are the mean ± SD. ns, no significant difference; ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, and ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001 by unpaired Student’s t test. See also Figure S3.