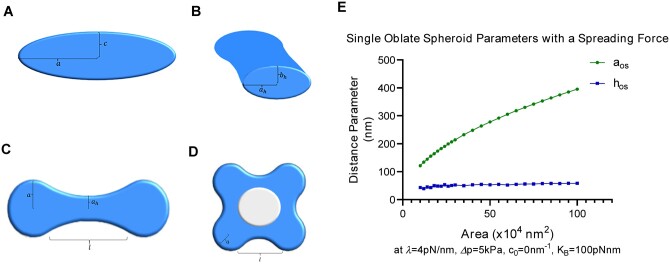

Figure 2.

Approximating cell plate structures using a variational approach. A–D, Examples of membrane structure parameterizations used for modeling. A, Cross-section of an oblate spheroid through the polar axis. The major axis radius is labeled and the minor axis radius is labeled . This structure is used to model vesicles, or mature cell plate structures in the case where . B, Cross-section of an elliptic hyperboloid at its center, showing the skirt radii. The hyperboloid can be parameterized by its length and its skirt radius in the equatorial plane , the skirt radius in the axial plane is given by , which can be written as a function of the other parameters listed as shown in Supplemental Equation S3. C, An example of a tubulo-vesicular structure parameterized by two oblate spheroids connected by a single elliptic hyperboloid (referred to as a 2 × 1 × 0 structure). Only the top view is shown. D, An example of a 4 × 4 × 1 conformation that models a transition to a fenestrated network with genus . E, Evolution of single oblate spheroid parameters in the presence of a spreading force. In the presence of a spreading force, the thickness of the oblate spheroid remains in the 40–80 nm range despite the increase in area. This reflects the thicknesses and growth patterns found in intermediate cell plate stages (Samuels et al., 1995). Here, = ( shown in A), represents the overall height, or thickness, of the oblate spheroid. In the absence of a spreading force, , or the thickness, is estimated to grow in values that are not observed experimentally. For reference, an area of is roughly equal to that of a single vesicle.