Abstract

Introduction

Workplace violence (WPV) against Healthcare Workers (HCWs) has emerged as a global issue. Emergency Department (ED) HCWs as front liners are more vulnerable to it due to the nature of their work and exposure to unique medical and social situations. COVID-19 pandemic has led to a surge in the number of cases of WPV against HCWs, especially against ED HCWs. In most cases, the perpetrators of these acts of violence are the patients and their attendants as families. The causes of this rise are multifactorial; these include the inaccurate spread of information and rumours through social media, certain religious perspectives, propaganda and increasing anger and frustration among the general public, ED overcrowding, staff shortages etc. We aim to conduct a qualitative exploratory study among the ED frontline care providers at the two major EDs of Karachi city. The purpose of this study is to determine the perceptions, challenges and experiences regarding WPV faced by ED healthcare providers during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods and analysis

For this research study, a qualitative exploratory research design will be employed using in-depth interviews and a purposive sampling approach. Data will be collected using in-depth interviews from study participants working at the EDs of Jinnah Postgraduate Medical Centre (JPMC) and the Aga Khan University Hospital(AKUH) Karachi, Pakistan. Thestudy data will be analysed thematically using NVivo V.12 Plus software.

Ethics and dissemination

The ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Aga Khan University Ethical Review Committee and from Jinnah postgraduate Medical Center (JPMC). The results of the study will be disseminated to the scientific community and to the research subjects participating in the study.

The findings of this study will help to explore the perceptions of ED healthcare providers regarding WPV during the COVID-19 pandemic and provide a better understanding of study participant's’ challenges concerning WPV during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Keywords: COVID-19, accident & emergency medicine, health policy

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This exploratory qualitative study will provide an in-depth understanding of the consequences and impact of work place violence (WPV) on front-line emergency department (ED) healthcare workers (HCWs) working in an low-to-middle-income county (LMIC) during the COVID-19 pandemic, which has not been fully explored in previous studies conducted in this context.

This is a multi-centre study, including participants from public as well as private sector EDs and can serve as a base for larger multi-centre quantitative/mixed methods studies involving ED HCWs across the country.

The results of this study will guide the development of context-specific interventions to address the challenges of HCWs in LMICs experiencing WPV during the COVID-19 pandemic.

This study will also guide the formulation of approaches and strategies to combat WPV in case of any other public health crisis related to frontline ED HCWs in the future.

One limitation of the study is that since the participants will being interviewed online, authors will not have the opportunity to build rapport with participants and record non-verbal cues.

Due to the sensitive nature of the issue of experiencing WPV, participants may be hesitant to touch on some emotional triggers during the online interview.

Background

Work place Violence (WPV) is referred to an act or threat of physical or verbal violence, harassment, terrorising or other intimidating behaviour occurring at a work-site that leads to a physical or psychological injury to the victim.1 WPV has evolved as a global issue and is regarded as an epidemic in some countries.2 International research has found that staff and patient attributes, the interaction between staff and patients, as well as environmental characteristics, are important factors associated with the occurrence of patient and visitor violence.3 Healthcare workers (HCWs) are more prone to it and it ranges from threats and verbal abuse to physical assaults and even homicide4 besides the impact on healthcare professionals, violence also, directly and indirectly, affects the quality of patient care.5–7 HCWs in the emergency department (ED) are more vulnerable to violence5 8 9 due to a variety of stressors including the overcrowding of ED, unresolved issues of emergency patients, disease stress, patient pain, high acuity of patient illness, rotating staff and late hours.7 9 10

The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic has become a threat to global health and the economy. Additionaly, it has drastically manipulated our daily lives and behaviour as a common man, alongside, HCWs being the frontline fighters in this pandemic are consistently & ferociously exposed to hazards that put their lives at risk. Hazards include pathogen exposure, long working hours, psychological distress, fatigue and occupational burnout. Health workers experience stress and concern about transmitting the disease to family members and experience a constant sense of intense fear, stigmatisation and ostracism when treating patients with COVID-19.11 Rather than gaining appreciation, HCW’s experience violent behaviour in the ED by the patients and their attendants. The reasons leading to such attacks include fear, anxiety, propaganda about the spread of the pandemic and inappropriate anger among the masses.12 Other factors causing psychological distress include conspiracy theories, global socioeconomic crisis, travel restrictions, adjournment of religious, sports, cultural, and entertainment events, panic buying and hoarding.13 These mental challenges make the people displace aggression on HCWs, serving as a direct threat to them. Highlighting here an incident that occured during the initial phase of the pandemic in Royal Adelaide Hospital, South Australia, where a patient who was initially compliant presented with alcohol intoxication and suspected COVID-19 infection, reported to ED and later became agitated at being kept in isolation, blocked the door to the ED healthcare staff and set fire to their belongings,14 this behaviour could potentially harm the HCWs and also affect patient care negatively. In some places like Mexico, HCWs are being accused of spreading the virus and are being attacked by the public, some patients have also been observed to purposely cough or spit on HCWs.11 HCWs are being physically assaulted not just in Mexico,15 but cases have also been reported in the Philippines, Australia and the USA.12 It is clear from the current epidemics in Europe and the USA that COVID-19 disease will place a severe strain on health systems. This effect is likely to be more extreme in low-income settings where healthcare capacity is typically limited. Paired with the threats of WPV, the healthcare facilies in low-to-middle-income countries (LMICs) have become more challenge-able workplaces. LMICs have reported that 60%–87.5% of emergency healthcare providers (eg: nurses and physicians) experience some form of WPV annually.16 Looking at the situation in South Asia, HCWs in India are being beaten, stoned, spat on, threatened and expelled from their homes.17 Despite dying of COVID-19 and getting hospitalised due to lack of personal protective equipment, violence against healthcare providers, especially doctors and nurses, is on the rise and COVID-19 wards are daily being attacked by attendants of patients who succumb to complications of the disease, as quoted by officials.18

In Pakistan, some serious incidences of WPV against ED frontline healthcare staff are reported by media at various public and private sector hospitals but many incidences are kept unreported. In light of these events in the country, The Pakistan Islamic Medical Association (PIMA) reported that doctors and paramedics were facing double jeopardy. ‘The workforce at the healthcare facilities in Pakistan is diminishing at a rapid pace due to COVID-19 since doctors and nurses are dying daily due to the lethal infection while treating patients, and on the other hand, people are subjecting them to violence, which is unacceptable’, said a member of PIMA, while talking to The News. In addition, he maintained that doctors and healthcare facilities were being attacked on daily basis throughout the country, and blamed the smear campaign against them on social media, ignorance of some people and lack of security at the healthcare facilities.18 COVID-19 pandemic has caused the hospitals to fill up, subsequently, HCWs are being subjected to physical assaults by the angry and frustrated patients and their attendants.18 19 The World Economic Forum asserts that women comprise the majority of frontline HCWs globally, meaning that female representation is vital in tackling the coronavirus crisis. Seventy per cent of the world’s healthcare staff are made up of women. Without women in these positions, women’s issues could fail to be addressed throughout the crisis.20 On the contrary, female doctors and nurses are being subjected to WPV in an unbiased manner as of yet. Female doctors and nurses are facing the brunt of the situation in the country and many female doctors and nurses are staying away from healthcare facilities due to the growing violence against them, the resources added as cited in media.18 A major incident of stoning and destroying the whole COVID-19 ward in the ED of a public sector hospital took place in Karachi, during the initial phase of the pandemic and similar episodes took place in other hospitals as well, but no substantial actions were taken against the individual responsible for such incidences.21 The outcomes of these incidences have a deleterious impact on the physical and mental health and well-being of ED’s HCWs and frontline staff. Conclusively, there have been data sets that enable the depiction of WPV on HCW’s globally; however, the current exploratory study is planned to seek perspectives of HCW’s in ED on the effects of WPV amidst the pandemic being a compromise to public health and HCW’s efficiency.

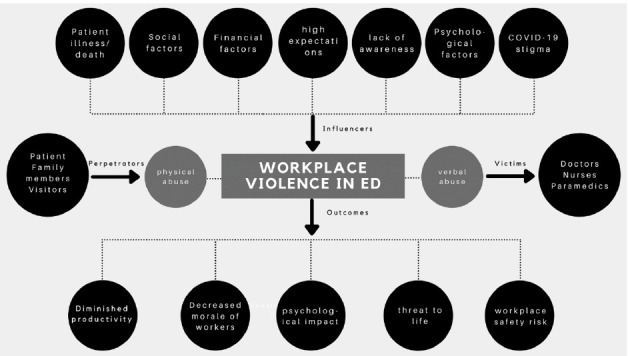

A study conducted on 179 physicians from 5 specialties to measure the association between experience of WPV and self-report of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression, anxiety and burnout reported that 1 in 6 physicians experienced physical abuse and 3 in 5 verbal abuse during their duty in the past year. PTSD symptoms were 6.7 times more commonly seen in those who experienced a physical attack.22 Another cross-sectional survey conducted in four of the largest tertiary care hospitals in Karachi, Pakistan which found that 16.5% of HCWs in ED, mainly nurses was physically assaulted and 72.5% experienced verbal abuse.23 WPV is a significant obstacle in the delivery of healthcare services which can be prevented by taking timely adequate actions. In the context of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, WPV is more frequent in the EDs leaving the HCWs vulnerable to such kinds of threats. Figure 1 depicts various factors contributing towards ED-WPV.

Figure 1.

Conceptualisation of factors in emergency department-work place violence during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods and analysis

Study design

A Qualitative exploratory research design will be employed using In-Depth Interviews (IDIs) and a purposive sampling approach. Descriptive exploratory qualitative design tends to be electric in data collection methods and designs based on general premises of constructive inquiry. The IDIs aim to explore the perceptions, challenges, and experiences regarding WPV faced by ED healthcare providers (doctors, nurses and frontline staff) during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Study setting and study participants

Data for this study will be collected from two purposively selected tertiary care hospitals (one public and one private) from Karachi, Pakistan. The study will be conducted at the EDs of Jinnah Postgraduate Medical Centre (JPMC) hospital and the Aga Khan University Hospital (AKUH) Karachi, Pakistan. The ED of JPMC receives the heaviest number of patients. AKUH is among the largest private tertiary care facility in the city. The study participants including (doctors, nurses, paramedics, pharmacists and admin staff) will be recruited through purposive sampling technique. We will only interview those participants who have been working full-time at ED since the COVID-19 outbreak in Pakistan. The objective to recruit medical and administrative staff is to explore the different perspectives and experiences of WPV at ED. Before starting the interview, the objective of the study will be shared, and written informed consent will be taken from the study participants. Only those respondents will be interviewed who will give consent and willing to participate in the study. The sample size will be determined through the ‘saturation principle’. When the researchers would observe that no more new information, themes and subthemes are emerging the data collection will be seized.

The sample size will be dependent. The purposive sampling follows the concept of theoretical saturation; this means we will include participants until the data have reached sufficient saturation to meet study objectives. The anticipated data collection followed by pilot testing will be from June 2021 till January 2022. However, we also anticipate some interruptions in data collection due to the intermittent COVID-19 surges that lead to increased workload of the frontline healthcare providers (anticipated number of participants and inclusion categories are also presented in the form of a table; see table 1).

Table 1.

Number and background of healthcare workers to be interviewed

| Type of HCPs | Number of participants to be interviewed |

| Physicians | 5 |

| Residents | 5 |

| Nurses | 5 |

| Paramedics | 3 |

| Pharmacists | 2 |

| Admin staff | 2 |

| Total (each site) | 22 |

Eligibility criteria

The following are the criteria for inclusion and exclusion of study participants.

Inclusion criteria

All ED frontline healthcare providers including doctors, nurses, paramedics, pharmacists, administration staff who are working in the ED irrespective of their status of being a victim of WPV will be included in the study.

Exclusion criteria

Refusal to consent for participation.

Data collection procedure

The data will be collected through IDIs with healthcare providers and administrative staff who have been directly or indirectly providing care of patients with COVID-19 in ED. The IDIs facilitate investigators to probe and understand the research question more precisely in the face-to-face direct communication. The data will be collected through a semistructured guide with several probing options. We anticipate conducting 22–25 IDIs with a group of ED frontline healthcare providers comprising doctors, nurses, paramedics, admin staff, and pharmacists at two tertiary care facilities (AKUH, JPMC). The data collection will be seized once sample saturation is achieved.

Data collection will be started after seeking Ethical Review Committee (ERC) approval from both the study sites. Written consent of the head of the department of ED before starting formal data collection. After seeking departmental permission, a list of staff will be obtained to contact study participants. The staff of ED will be approached through in-person, phone and email to schedule a meeting for an interview. The interview guide will be shared through email after scheduling the interview time. The brief biography of the interviewer will also be shared with the interviewee before starting the interview. Data will be collected face-to-face interviews and on the Zoom call according to the preference and availability of interviewee. Data will be collected by the Principal Investigator (PI) MN along with coinvestigators(HA-SA) in Urdu and English. Before data collection, consent of recording and note-taking will be taken from participants. If the interviewee will hesitate of being recorded his/her interview, then only notes will be taken by the coauthor. Before starting the interview, the study’s introduction and objectives will be explained. Confidentiality and anonymity of the participants will be maintained by the interviewer. At the end of the interview, participants will be asked any questions and share their feedback.

Study tool: the IDI guide

The interview guide is developed after an intensive literature review, discussion with healthcare providers and administrative staff. We have also cited some relevant literature for the pertinence of our guide and tailored the available literature-based guide according to our study question.9 24 The semistructured guide will be pilot tested before actual data collection and will be periodically updated during data collection. The guide is structured in a way that there is a flow of information coming from the participants in a continuum. The guide consists of sections based on demographic information, workplace-related information, duration of experience of ED healthcare providers, events of WPV, and questions pertaining to their perception and challenges on WPV during the pandemic. The IDI guide is also attached as a separate file (online supplemental material A).

bmjopen-2021-055788supp001.pdf (87.8KB, pdf)

Patient and public involvement

Patients or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of our research.

Data analysis

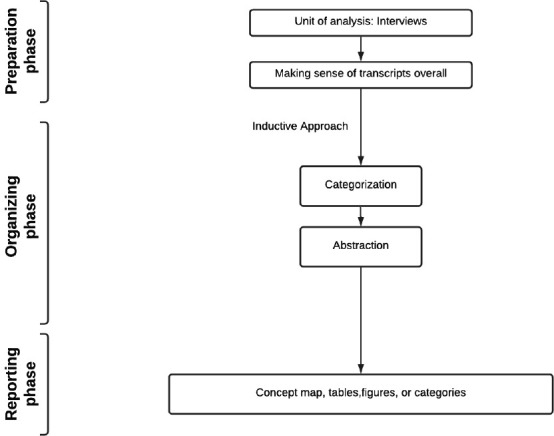

A preliminary training for carrying out data analysis will be carried out by qualitative experts(ASF and MA). The audio recordings and written notes will be transcribed and translated into English by MN and SA. The translated data will be counter-checked with audio recordings to ensure the quality of transcripts by (MN & ASF). The data will be analysed through the inductive approach on NVivo computer software. The analysis will consist of three main phases: preparation, organising, and reporting (figure 2). Thepreparation phase will include the identification of the unit of analysis, which will be the interviews of ED HCWs, and then making sense of the data as a whole. The organising phase will consist of inductive analysis. For inductive analysis, categorisation (making categories) and abstraction (further simplifying and making subcategories) will be done. This will help with grouping the data, for better understanding and generating knowledge25 The analysis approach (thematic content-based) will use a combination of predetermined and self-derived themes facilitated by observation, formal and informal discussions with study participants. Major themes and subthemes will be identified through detailed readings of transcripts and patterns of data. A codebook of relevant quotes will be generated from the data as well as concepts of interest at the outset of the study. The study themes, subthemes and quotes will be discussed among all the study investigators and discrepancies will be discussed during the analysis and interpretation of the data. The design and reporting of data will be based on the Consolidated criteria for Reporting Qualitative research(COREQ) guidelines.26

Figure 2.

Thematic approach for content analysis.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethical approval for this study will be obtained from the Aga Khan University ERC. A separate ERC will be taken for the study from JPMC as well. The study objectives and voluntary nature of the study will be explained to the participants, and oral informed consent will be obtained before each online interview. Confidentiality of participants will be maintained by placing deidentifiers instead of names and their designations (eg, physician P1, P2, etc and nurse N1, N2, etc). Also, information regarding the participant’s identity will be removed from transcripts. All audio recordings and transcripts will be saved on a password-protected computer.

Discussion

Our research will help to explore the perceptions of ED healthcare providers (doctors, nurses and frontline staff) regarding WPV during the COVID-19 pandemic. Specifically, the findings of the qualitative study will provide a better understanding of study participants’ challenges about WPV during COVID-19 pandemic. Finally, this study would suggest strategies to improve the overall experiences of HCWs working in EDs of the public and private hospitals during the COVID-19 pandemic. The study would also guide the development of context-specific interventions to address challenges of frontline ED HCWs regarding WPV during the COVID-19. The study may also serve as a strong base for a multicentre quantitative/mixed methods study at a larger sample size among ED HCWs across the country.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: MN is the Principal Investigator(PI) conceptualized the whole study, was involved study design, protocol design, IRB/ERC approval, methodology, development of study tool, data analysis plan, medical literature review, article writing, reviewing and editing. ASF is the Co-Principal Investigator and was involved in study design, protocol design, plan of analysis, methodology and article writing. HA was responsible for medical literature review and article writing. SA was responsible for medical literature review and article writing. MA was involved in methodology and article writing. SJ is the Co-Investigator and was involved in ERC approval and article writing. AM is the Co-Investigator/collaborator and was involved in project feedback, support, as well as article writing.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

References

- 1.Merchant JA, JAJAjopm L. Background, rationale, and summary. In: Workplace violence intervention research workshop, April 5–7, 2000. Washington, DC, 2001: 135–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Escribano RB, Beneit J, Luis Garcia J. Violence in the workplace: some critical issues looking at the health sector. Heliyon 2019;5:e01283. 10.1016/j.heliyon.2019.e01283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hahn S, Müller M, Needham I, et al. Factors associated with patient and visitor violence experienced by nurses in general hospitals in Switzerland: a cross-sectional survey. J Clin Nurs 2010;19:3535–46. 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2010.03361.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Erkol H, Gökdoğan MR, Erkol Z, et al. Aggression and violence towards health care providers--a problem in Turkey? J Forensic Leg Med 2007;14:423–8. 10.1016/j.jflm.2007.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Association ENAJEN . Position statement: violence in the emergency care setting, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 6.JBC L, Magarey J, McCutcheon H. Violence in the emergency department: a literature review. Australas Emerg Nurs J 2004;7:27–37. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hedayati Emam G, Alimohammadi H, Zolfaghari Sadrabad A, et al. Workplace violence against residents in emergency department and reasons for not reporting them; a cross sectional study. Emerg 2018;6:e7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chappell D, Martino D. Violence at work. International Labour Organization, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davey K, Ravishankar V, Mehta N, et al. A qualitative study of workplace violence among healthcare providers in emergency departments in India. Int J Emerg Med 2020;13:33. 10.1186/s12245-020-00290-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marx J, Walls R, Hockberger R. Rosen’s emergency medicine-concepts and clinical practice. Elsevier Health Sciences, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rodríguez-Bolaños R, Cartujano-Barrera F, Cartujano B, et al. The urgent need to address violence against health workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Med Care 2020;58:663. 10.1097/MLR.0000000000001365 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McKay D, Heisler M, Mishori R, et al. Attacks against health-care personnel must stop, especially as the world fights COVID-19. Lancet 2020;395:1743–5. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31191-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mukhtar S. Psychological health during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic outbreak. Int J Soc Psychiatry 2020;66:512–6. 10.1177/0020764020925835 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lightfoot J, Harris D, Haustead D. Challenge of managing patients with COVID-19 and acute behavioural disturbances. Emerg Med Australas 2020;32:714–5. 10.1111/1742-6723.13522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Semple K. “Afraid to be a nurse”: health workers under attack, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Benjamin Lindquist KWK, Gennosa C, Mahadevan A. Workplace Violence Experienced by Emergency Medical Technicians in India American Academy Of Emergency Medicine April 07, 2018 - April 11, 2018. Cureus 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Withnall A. Coronavirus: why India has had to pass new law against attacks on healthcare workers, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bhatti MW. Facing covid-19 and violence simultaneously, healthcare community in Pakistan has lost 24 colleagues so far. The News, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 19.SMaMA-H Zur-R. Pakistan’s Lockdown Ended a Month Ago. Now Hospital Signs Read ‘Full.’. The New York Times, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jeremy Farrar GRG. Why we need women’s leadership in the COVID-19 response. World Economic Forum, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bhatti MW. Attendants of deceased vandalise JPMC ward, claim coronavirus does not exist. The News, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zafar W, Khan UR, Siddiqui SA, et al. Workplace violence and self-reported psychological health: coping with post-traumatic stress, mental distress, and burnout among physicians working in the emergency departments compared to other specialties in Pakistan. J Emerg Med 2016;50:167–77. 10.1016/j.jemermed.2015.02.049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zafar W, Siddiqui E, Ejaz K, et al. Health care personnel and workplace violence in the emergency departments of a volatile Metropolis: results from Karachi, Pakistan. J Emerg Med 2013;45:761–72. 10.1016/j.jemermed.2013.04.049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vrablik MC, Chipman AK, Rosenman ED, et al. Identification of processes that mediate the impact of workplace violence on emergency department healthcare workers in the USA: results from a qualitative study. BMJ Open 2019;9:e031781. 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-031781 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Elo S, Kyngäs H. The qualitative content analysis process. J Adv Nurs 2008;62:107–15. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care 2008;19:349–57. 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2021-055788supp001.pdf (87.8KB, pdf)