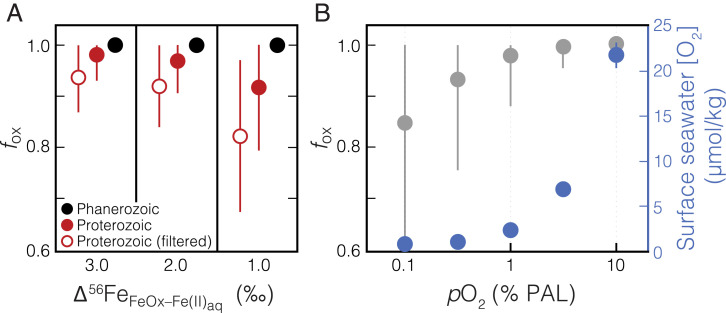

Fig. 4.

A model for Fe(II) oxidation in Proterozoic and Phanerozoic ironstones as a function of atmospheric pO2. (A) Using a Rayleigh distillation model, the fraction of the shallow seawater Fe(II) reservoir oxidized (fox) can be estimated based upon each ironstone Fe isotope value (i.e., more positive δ56Fe values indicate a lesser extent of oxidation; SI Appendix). Assuming three different scenarios for the overall isotope fractionation effect of the combined processes of Fe(II) oxidation and precipitation as Fe(III) (oxyhydr)oxides (Δ56FeFeOx–Fe(II)aq = 1.0, 2.0, and 3.0‰), mean results for fox are shown for the combined Proterozoic data (filled red circles) and combined Phanerozoic data (filled black circles). Error bars show ±1σ for the estimated fox values of the entire subsampled dataset. Given that positive δ56Fe values can only be explained by low [O2], yet a range of lower δ56Fe values are expected in this scenario, minimum fox estimates based upon the degree of fractionation within a sample set are relevant to estimating background [O2] levels. Therefore, we also calculate a range of minimum fox estimates by filtering Proterozoic data to exclude nonfractionated samples relative to the range of likely input values (−0.5 < δ56Fe < 0.3‰; open red circles). Shown in B are results for fox estimated from a kinetic model of Fe(II) oxidation, resampled 10,000 times at each atmospheric pO2 value (relative to PAL), across a range of seawater pH and temperature values (SI Appendix). Error bars show ±1σ. The corresponding surface seawater [O2] values at each atmospheric pO2 value, assuming gas-exchange equilibrium (42), are shown in blue. The systematics of the observed Proterozoic samples are difficult to explain unless atmospheric pO2 was below ∼1% PAL, while Phanerozoic data imply a minimum atmospheric pO2 of ∼5% PAL.