Abstract

Background

The COVID-19 pandemic has reduced access to endomyocardial biopsy (EMB) rejection surveillance in heart transplant (HT) recipients. This study is the first in Canada to assess the role for noninvasive rejection surveillance in personalizing titration of immunosuppression and patient satisfaction post-HT.

Methods

In this mixed-methods prospective cohort study, adult HT recipients more than 6 months from HT had their routine EMBs replaced by noninvasive rejection surveillance with gene expression profiling (GEP) and donor-derived cell-free DNA (dd-cfDNA) testing. Demographics, outcomes of noninvasive surveillance score, hospital admissions, patient satisfaction, and health status on the medical outcomes study 12-item short-form health survey (SF-12) were collected and analyzed, using t tests and χ2 tests. Thematic qualitative analysis was performed for open-ended responses.

Results

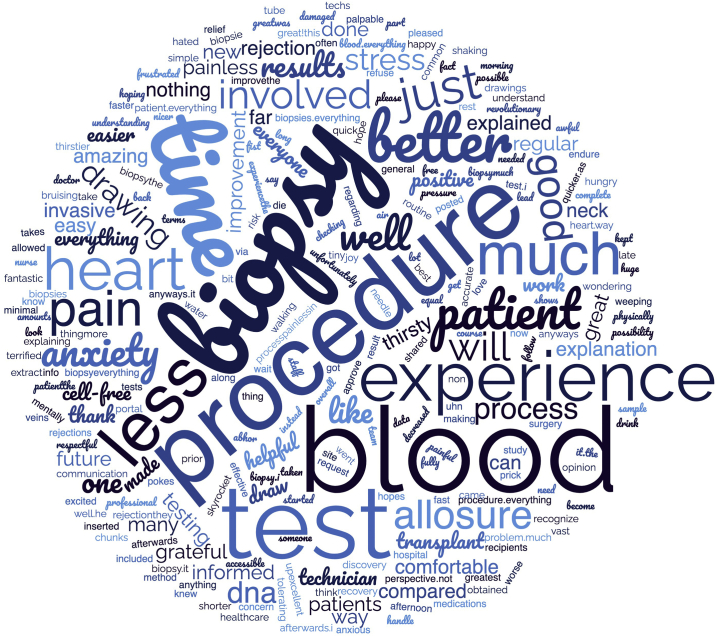

Among 90 patients, 31 (33%) were enrolled. A total of 36 combined GEP/dd-cfDNA tests were performed; 22 (61%) had negative results for both, 10 (27%) had positive GEP/negative dd-cfDNA results, 4 (11%) had negative GEP/positive dd-cfDNA results, and 0 were positive on both. All patients with a positive dd-cfDNA result (range: 0.19%-0.81%) underwent EMB with no significant cellular or antibody-mediated rejection. A total of 15 cases (42%) had immunosuppression reduction, and this increased to 55% in patients with negative concordant testing. Overall, patients’ reported satisfaction was 90%, and on thematic analysis they were more satisfied, with less anxiety, during the noninvasive testing experience.

Conclusions

Noninvasive rejection surveillance was associated with the ability to lower immunosuppression, increase satisfaction, and reduce anxiety in HT recipients, minimizing exposure for patients and providers during a global pandemic.

Graphical abstract

Résumé

Contexte

La pandémie de COVID-19 a réduit l’accès à la biopsie endomyocardique pour surveiller le risque de rejet après une greffe du cœur. Cette étude est la première à être menée au Canada pour évaluer le rôle de la surveillance non invasive du risque de rejet en personnalisant le titrage de l’immunosuppression et la satisfaction du patient après la greffe cardiaque.

Méthodologie

Dans le cadre de cette étude de cohorte prospective à méthodes mixtes, des adultes ayant reçu une greffe cardiaque depuis plus de six mois ont vu leurs biopsies endomyocardiques régulières remplacées par une surveillance non invasive du risque de rejet qui consiste à établir le profil de l’expression génique et à analyser l’ADN acellulaire dérivé du donneur. Les données démographiques, les résultats du score de surveillance non invasive, les admissions à l’hôpital, la satisfaction des patients et l’état de santé tirés du questionnaire SF-12 (questionnaire abrégé sur la santé comprenant 12 items) de l’étude sur les issues médicales ont été colligés et analysés au moyen des tests T et des tests χ2. Les réponses ouvertes ont fait l’objet d’une analyse qualitative thématique.

Résultats

Parmi 90 patients, 31 (33 %) ont été recrutés. Au total, 36 tests combinés de profilages de l’expression génique et d’ADN acellulaire dérivé du donneur ont été réalisés; les résultats ont été négatifs pour les deux tests dans 22 cas (61 %), positifs pour le profilage de l’expression génique et négatifs pour l’ADN acellulaire dans 10 cas (27 %), négatifs pour le profilage de l’expression génique et positifs pour l’ADN acellulaire dans quatre cas (11 %) et aucun cas n’a donné de résultats positifs pour les deux types de tests. Tous les patients qui ont donné des résultats positifs à l’analyse de l’ADN acellulaire dérivé du donneur (fourchette : 0,19 % à 0,81 %) ont subi une biopsie endomyocardique n’ayant révélé aucun rejet cellulaire ou à médiation par anticorps important. Au total, 15 cas (42 %) affichaient une immunosuppression réduite, proportion qui a grimpé à 55 % chez les patients dont les tests de concordance ont donné des résultats négatifs. Dans l’ensemble, le niveau de satisfaction rapporté par les patients était de 90 % et, à l’analyse thématique, ils étaient plus satisfaits et moins anxieux pendant les tests non invasifs.

Conclusions

La surveillance non invasive du risque de rejet a été associée à la capacité de diminuer l’immunosuppression, d’augmenter la satisfaction et de réduire l’anxiété chez les patients qui ont reçu une greffe cardiaque, en plus de réduire l’exposition des patients et du personnel médical dans le contexte d’une pandémie.

Survival after heart transplantation (HT) has significantly increased since the standardization of the monitoring and treatment of allograft acute cellular rejection (ACR). Universally, HT programs have protocolized surveillance endomyocardial biopsies (EMBs) to monitor for allograft rejection as the “gold standard.” However, the desire to replace or reduce the number of biopsies remains, given their cost, invasiveness, and potential for complications.1, 2, 3, 4 This desire has been amplified during the COVID-19 pandemic, during which access has been reduced for invasive care, and alternative noninvasive methods to monitor for ACR are particularly relevant.

Indeed, during the COVID-19 pandemic, our institution has experienced closures in the catheterization lab, as well as limited procedure times due to pandemic restrictions and personnel redeployment. Thus, we were unable to use routine EMB to safely reduce immunosuppression in cardiac transplant recipients and required alternative surveillance monitoring to assist with immunosuppression titration in these patients.

Significant advances have been made in the field of novel transplant-rejection biomarkers. Other centres are beginning to use noninvasive screening methods to follow HT patients remotely and reduce hospital visits and procedures.5 Gene expression profiling (GEP) (AlloMap, CareDx Inc., Brisbane, CA), a noninvasive blood test for the surveillance of transplant recipients, reduces the frequency of EMB, with no difference in adverse outcomes.2,3 However, GEP has limitations in that it cannot be used within 55 days of HT or in the setting of recent high-dose immunosuppression, as these factors can influence the predictive value of GEP testing, and these patients were excluded from trials.3,6,7 GEP may be falsely positive in recipients with active viral infections and should be interpreted with caution in this cohort.3,6,7

More recently, donor-derived cell-free DNA (dd-cfDNA; AlloSure, CareDx Inc.) from peripheral blood samples has been safely used to rule out ACR and antibody-mediated rejection (AMR) as early as 2 weeks after transplantation and allows for surveillance of rejection in HT recipients.8 HeartCare (CareDx Inc.) provides a comprehensive assessment of graft rejection by combining GEP and dd-cfDNA—the tests complement each other to provide a more holistic picture of graft health.9

Using blood samples to rule out rejection reduces the need for invasive surveillance and potential complications associated with invasive EMB. Noninvasive surveillance reduces procedural risk to patients and leads to improved patient satisfaction and health status survey scores.2,3

In this study, we aimed to reduce the number of EMBs in HT recipients by using combined noninvasive screening kits. The goal was to provide surveillance monitoring for rejection and immunosuppression adjustments, improve patient quality of life, and mitigate risk during invasive testing to HT patients and healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods

This study used mixed methods with a convergent, parallel design, collecting quantitative and qualitative data simultaneously but analyzing results separately. First, a prospective cohort study of HT patients was screened by the study team for eligibility to have their EMBs replaced by noninvasive screening. Second, thematic analysis was conducted on open-ended survey results. The study was approved by the University Health Network Quality Improvement Review Committee with a waiver of consent from the research ethics board (QI 21-0420).

Patient selection

Eligible HT recipients included adult patients (age > 17 years) undergoing surveillance EMBs at least 6 months post-HT. Patients were excluded if they were multi-organ transplant recipients, required dialysis, were less than 6 months after HT, or were at high risk for rejection (recent International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation [ISHLT] ACR ≥ grade 2R rejection [on one of prior 2 biopsies in the past 6 months], new graft dysfunction [drop in left ventricular ejection fraction by 15% or more on echocardiogram], or patient-reported symptoms of heart failure). This study was part of a quality-improvement initiative, so no randomization or control groups were used. If participants met the inclusion criteria, they were evaluated by our transplant team. If no exclusion criteria were met, participants were scheduled for noninvasive testing.

GEP and dd-cfDNA protocol

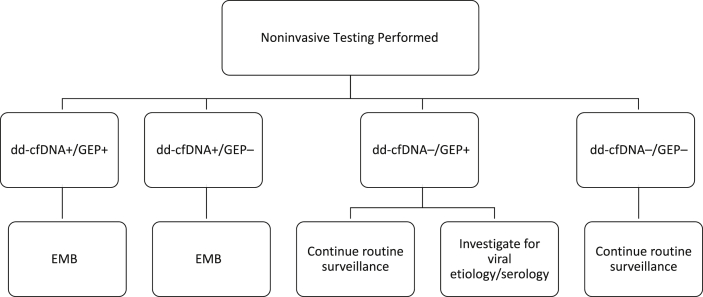

Patients were enrolled during the third wave of the COVID-19 pandemic (from May 2021 to August 2021) and had their routine EMBs replaced by noninvasive screening with combined GEP and dd-cfDNA kits. Adjustment to immunosuppression and routine care was provided to all patients based on our previously established HT program protocol. A high-risk or positive AlloMap score was ≥ 34 for rejection, but an abnormal result on GEP did not mandate a biopsy. A threshold dd-cfDNA level of ≤ 0.15% was used to rule out significant rejection. If the dd-cfDNA result was positive, then a “for cause” EMB occurred to screen for histopathologic signs of rejection (ACR and/or AMR; Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Action flow map for noninvasive surveillance testing. dd-cfDNA, donor-derived cell-free DNA; EMB, endomyocardial biopsy; GEP, gene expression profiling. +, positive test result; –, negative test result.

Data were collected on patient demographics, medical history after transplantation, rejection history, immunosuppression, infection prophylaxis at the time of testing, and allograft function. The outcomes of HeartCare kit score, death, admission to hospital, patient quality of life, and patient satisfaction were also collected. Health-related quality of life was measured using the Medical Outcomes Study 12-item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-12) mental and physical health component scores (Supplemental Appendix S1) and a patient satisfaction survey (Supplemental Appendix S2).10 Patients completed the survey after having their noninvasive blood draw completed. For the duration of time post-HT (minimum of 6 months), all patients had prior experience with EMB and could compare this experience to that of noninvasive testing.

Qualitative analysis

Thematic analysis was performed for open-ended responses from the patient satisfaction survey. The words of participants were examined carefully, and recurring ideas were separated into different codes, consistent with the NVivo coding process described by Miles et al.11 Codes were selected and thematic analysis was used to establish themes and assertions to interpret qualitative data.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are presented as median (interquartile range [IQR]), and categorical variables are presented as frequency. Comparisons between groups were done, using the Student t test or Mann-Whitney U test for continuous variables according to normality, and the χ2 test or Fisher test for categorical variables.

Results

Demographics

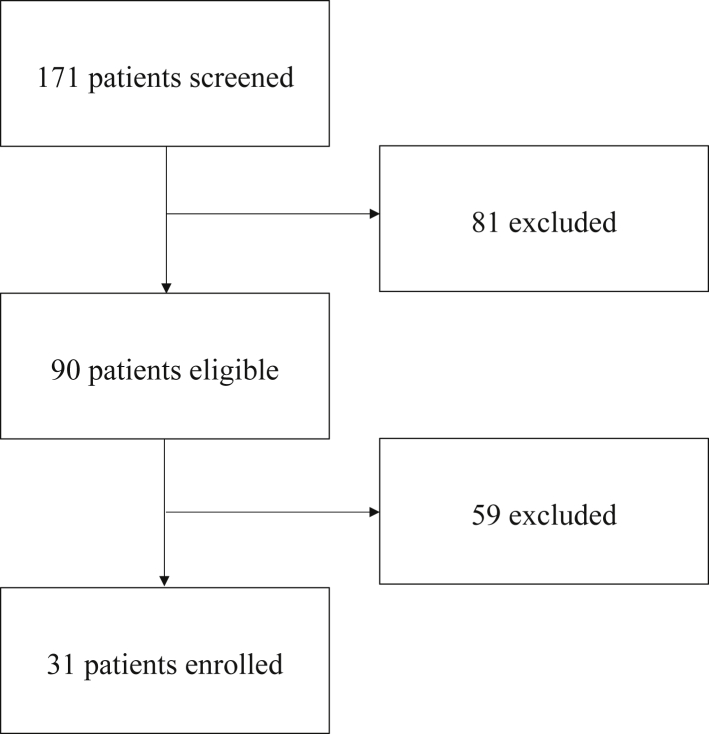

A total of 171 patients were scheduled for EMBs over the enrollment period; 81 of these were excluded, and 90 were eligible. Among the 90 remaining patients after exclusion criteria were applied, 31 (33%) were enrolled to have their routine EMBs replaced by noninvasive rejection screening, owing to the limited number of testing kits for eligible participants (Fig. 2). Of the 37 kits processed, 36 combined total tests were available. The median time since HT was 1.9 years (IQR: 1.1, 6.4 years) (Supplemental Fig. S1). As shown in Table 1, this cohort was predominantly male (68%) and Caucasian (52%), with the primary reason for transplant being related to a nonischemic etiology (51.6%). With regard to graft function, 10% had a history of primary graft dysfunction, 32% had a history of cardiac allograft vasculopathy, 53% had a history of treated ACR at 1 year, and 7% had a history of treated AMR. The majority of patients (84%) remained on prednisone at the time of noninvasive testing.

Figure 2.

Patient flow diagram.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of participants

| Characteristic | Total (N = 31) |

|---|---|

| Age at heart transplant, y | 47.6 (33.0–60.9) |

| Female | 10 (32.3) |

| Race | |

| Caucasian | 16 (51.6) |

| Black | 5 (16.1) |

| Asian | 7 (22.6) |

| Mixed | 3 (9.7) |

| Indication for cardiac transplant | |

| Nonischemic | 16 (51.6) |

| Ischemic | 6 (19.4) |

| Hypertrophic | 5 (16.1) |

| Congenital | 1 (3.2) |

| Other | 3 (9.7) |

| Bridged with durable LVAD | 10 (32.3) |

| Bridged with CMAG or ECMO | 4 (12.9) |

| Medical history after transplant | |

| Hypertension | 17 (54.8) |

| Diabetes | 14 (45.2) |

| Chronic kidney disease | 10 (32.3) |

| Graft function | |

| Pacemaker | 6 (20.0) |

| History of primary graft dysfunction | 3 (10.0) |

| Cardiac allograft vasculopathy | 9 (32.1) |

| Acute cellular rejection at 1 year | 16 (53.3) |

| Treated antibody-mediated rejection | 2 (6.7) |

| Persistent donor-specific antibody | 7 (23.3) |

| History of graft impairment (LVEF < 50%) | 4 (12.9) |

| LVEF, % | 61.0 (57.0–65.0) |

| Complications after transplant | |

| Cancer | 3 (10.0) |

| Treated CMV | 5 (16.7) |

| Immunosuppression | |

| Prednisone | 26 (83.9) |

| Tacrolimus | 23 (74.2) |

| Cyclosporine | 5 (16.1) |

| Mycophenolic acid | 24 (77.4) |

| Sirolimus | 10 (32.3) |

Data are presented as median (interquartile range) and count (percentage) for continuous and categorical data, respectively. Graft dysfunction was defined as any history of decline in LVEF of 15% or more from baseline.

CMAG, CentriMag biventricular assist device; CMV, cytomegalovirus; ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; LVAD, left ventricular assist device; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction.

GEP and dd-cfDNA testing

A total of 36 combined tests were conducted, among which 22 (61%) had a negative GEP and dd-cfDNA result; 10 (28%) had a negative dd-cfDNA but a positive GEP result, and 4 (11%) had a negative GEP but a positive dd-cfDNA result. None had both a positive dd-cfDNA and GEP result (Table 2). All 4 patients with a positive dd-cfDNA result (range: 0.19%-0.81%) underwent EMB; 2 patients had ISHLT ACR grade 1R, and 2 patients had grade 0 rejection. One patient with a positive dd-cfDNA test result was within 6 months post-HT, and 3 were ≥ 1 year post-HT. None of the patients had evidence of AMR (all ISHLT AMR 0). Five patients had serial combined testing as shown in Table 3. Overall, noninvasive screening safely eliminated 32 EMBs (89%).

Table 2.

Combination matrix for noninvasive testing for GEP (positive threshold ≥ 34) and dd-cfDNA (positive threshold > 0.15%)

| dd-cfDNA |

Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive | Negative | |||

| GEP | Positive | 0 | 10 | 10 |

| Negative | 4 | 22 | 26 | |

| Total | 4 | 32 | 36 | |

dd-cfDNA, donor-derived cell-free DNA; GEP, gene expression profiling.

Table 3.

GEP score and dd-cfDNA level results for patients with serial testing

| 1st GEP score | 1st dd-cfDNA level, % | 2nd GEP score | 2nd dd-cfDNA level, % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 35 | ≤ 0.15 | 35 | ≤ 0.15 |

| 2 | 37 | ≤ 0.15 | 34 | ≤ 0.15 |

| 3 | 28 | ≤ 0.15 | 29 | ≤ 0.15 |

| 4 | 33 | ≤ 0.15 | 28 | ≤ 0.15 |

| 5 | 29 | ≤ 0.15 | 33 | 0.32 |

dd-cfDNA, donor-derived cell-free DNA; GEP, gene expression profiling.

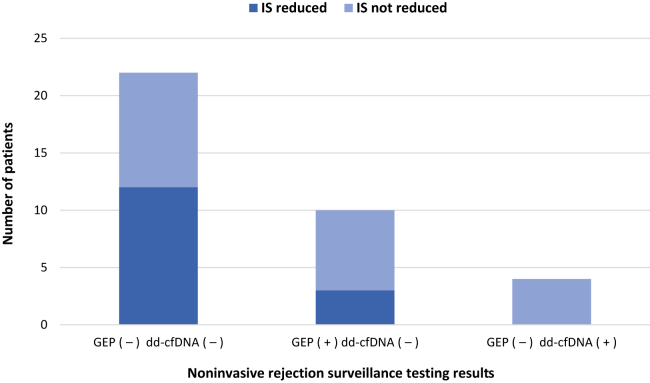

Changes in immunosuppression

Baseline immunosuppression dose and/or drug levels were determined for all enrolled HT patients, and stratified by time posttransplant (Supplemental Table S1). In 15 cases (42%), testing results triggered a decrease in immunosuppression dosage. In patients who had a negative concordant test, immunosuppression was reduced among 55%, and it was reduced in 30% among those with a positive GEP and a negative dd-cfDNA test result (Fig. 3). Specifically, 80% of patients had a reduction in prednisone, 13% had a reduction in mycophenolic acid, and 7% had a reduction in calcineurin inhibitor.

Figure 3.

Instances of reduction in immunosuppression (IS) stratified by noninvasive rejection surveillance testing results (n = 36). Positive gene expression profiling (GEP) was a score ≥ 34 and donor-derived cell-free DNA (dd-cfDNA) positive test results (+) were > 0.15%. No patients had concordant testing in the category of gene expression profiling (GEP +) dd-cfDNA (+). (–), negative test result.

COVID-19 and GEP

In our cohort, 17 patients (51%) had received 2 COVID-19 vaccines, and 1 had contracted COVID-19 at 6 months prior to noninvasive testing. A total of 23.8% of the tests after vaccination had a positive GEP result, compared with 33.3% of those performed in nonvaccinated patients (P = 0.690). The median time from vaccine to noninvasive testing was 51 days (IQR: 17, 66 days). No significant relationship was seen between the score positivity and the time from vaccination. No difference was seen in the median GEP scores between those who were vaccinated and those who were not (GEP score in vaccinated, 30.0, vs 33.5, P = 0.721).

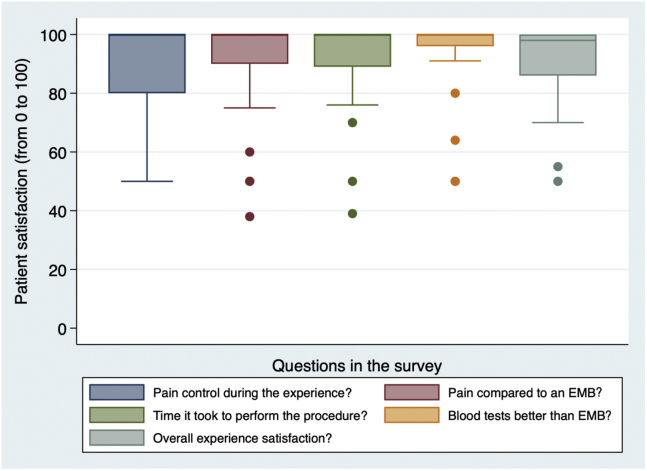

Health status and patient satisfaction

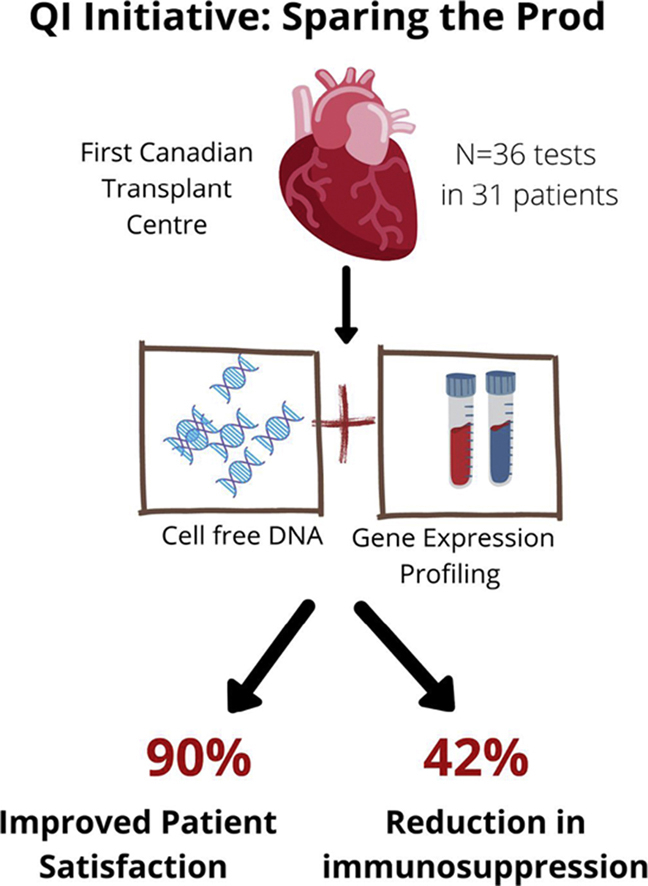

All patients completed the SF-12 and a patient satisfaction survey. Patients’ self-reported satisfaction was 90%, indicating the following: they were very satisfied with noninvasive biomarkers; testing was less painful; they had good pain control; and they had a greater preference for noninvasive surveillance testing, compared with EMB (Fig. 4). The median anxiety-level score was 50 (IQR: 10, 71) prior to EMB, compared with 2.5 (IQR: 0, 7.5) prior to noninvasive testing (Fig. 5A). The median physical health score was 43 (IQR: 37, 53), and the median mental health score was 53 (IQR: 44, 58; Fig. 5B). A mean score of 50 points out of 100 represents the US population average.

Figure 4.

Patient satisfaction with noninvasive rejection surveillance screening by blood test, compared with that for invasive endomyocardial biopsy (EMB; n = 29).

Figure 5.

Patient-reported anxiety and medical outcomes study 12-item short-form health survey (SF-12) scores. (A) Boxplot comparison of patient median anxiety rating before endomyocardial biopsy (EMB) or noninvasive rejection screening blood test with gene expression profiling (GEP) and donor-derived cell-free DNA (dd-cfDNA) as measured on a self-reported scale from 0 to 100 (n = 28). (B) Boxplot comparison of median SF-12 score for physical health component score (PCS) and mental health component score (MCS) from 0 to 100 (n = 31).

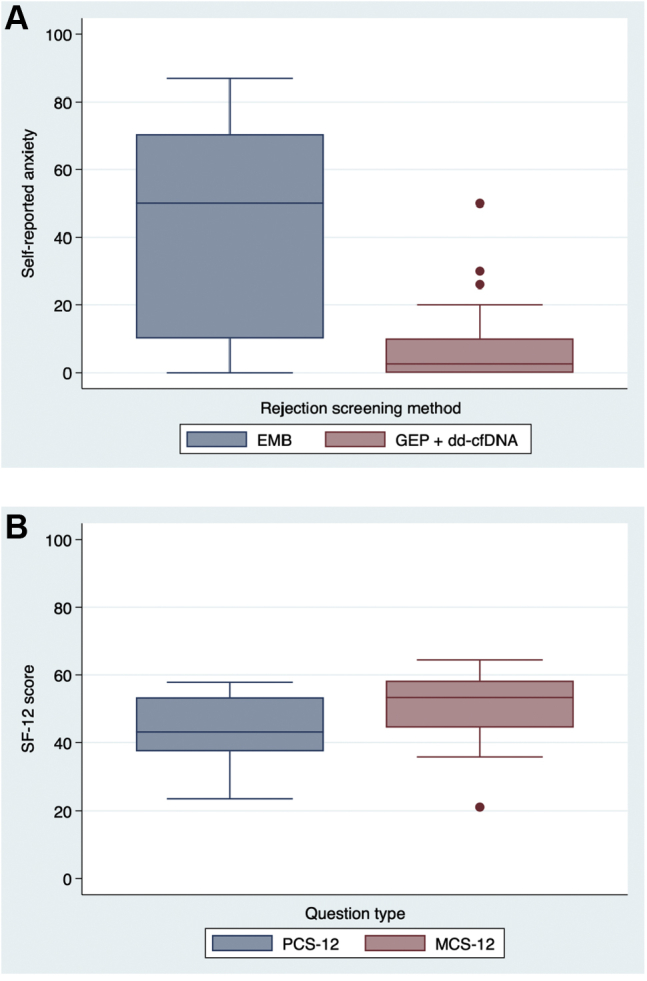

For qualitative data from patient satisfaction surveys, 4 codes (“emotions” [pain, anxiety, fear], “time,” “compared to biopsy,” and “accuracy”) were used to analyze data. This process uncovered 2 common themes: “superiority to biopsy” (codes: emotions, time, compared to biopsy); and “mental or physical stress” (codes: emotions, time, accuracy). Patients described feeling more satisfied and less emotionally distressed with the noninvasive screening. Reasons included that they felt this test was superior to a biopsy (“so much less invasive,” “no pain or any recovery time as compared to biopsy,” and “much faster”). A visual representation of the qualitative open-ended survey responses was created in the form of a word cloud (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

Word-cloud visual representation of participants’ open-ended survey responses.

Multiple emotions were captured under the theme of “mental or physical stress” that patients were able to avoid by replacing a painful, invasive, or very stressful procedure with something as simple and relatively painless as a blood draw. The noninvasive screening increased patient satisfaction with “no stress and concern” and being “much less pain, anxiety and quicker.” All participants reported increased satisfaction with noninvasive testing, reflected by combined themes of superiority to biopsy and reduced mental or physical stress, as indicated by the following responses:

• “I am so excited that there is a new way to test rejection! [Before a biopsy] I was terrified and started weeping and shaking . . . each time my anxiety would skyrocket. . . . Each time, I knew there was the possibility that I would die. The tiny needle prick to extract DNA info was amazing!!! I am so grateful.”

• “Quick, painless and stress free. Anything is better than a heart biopsy.”

Negative feedback on the noninvasive testing included patients' concerns about interpretation of these new results. Overall, patients were more satisfied, had less fear and anxiety, and were pleased with the experience of noninvasive testing.

Discussion

EMBs are used to diagnose or exclude rejection as part of a routine surveillance protocol that can allow for the reduction of higher doses of immunosuppression with its associated toxicities.1,2 Despite resource limitations and concerns of infection during COVID-19, continuing to taper immunosuppression to the lowest tolerated levels is essential to avoid potential complications of its long-term use, such as malignancy and early and late post-HT infections.1,12,13 In our patient population, 84% were on prednisone, highlighting the importance of ongoing surveillance and reduction of immunosuppression. Patients with higher prednisone doses have greater risk of infection episodes,12 and our group has shown that tapering off prednisone within the first year is associated with reduced risk of cardiac allograft vasculopathy.13

Noninvasive screening tests—ie, GEP and dd-cfDNA, are proving to be safe, practical, and desired methods of surveillance, with high levels of patient satisfaction.2,3,8,14 Our study, a quality-improvement initiative during COVID-19, allowed us to continue rejection surveillance and guide medical decisions at a time when access to biopsy procedures was limited. Through this initiative, 89% of invasive EMB procedures were safely eliminated in our cohort. Although many HT recipients could have had their biopsies delayed to a later time, this initiative allowed for further reduction of immunosuppression in nearly half of the patients who underwent noninvasive surveillance. A strength of this study is that, despite a global pandemic, we found that qualitatively, from the patients’ perspective, they had reduced anxiety and increased satisfaction with noninvasive screening. In immunocompromised patients, minimizing risk during waves of rising COVID-19 cases and reducing patients’ anxiety surrounding testing are important to prevent nosocomial infection, reduce mental health burden, and improve quality of life. Given this, we hope to continue this resource-allocation strategy as the pandemic wanes.

Although the EMB is a gold standard, variability in agreement of histopathologic assessments does result in unnecessary anti-rejection therapies and/or hospital admission.15, 16, 17 Even experienced cardiac pathologists can overrate moderate rejection (ISHLT ACR ≥ grade 2R), with low agreement when classifying significant ACR ( ≥ grade 2R), which has important implications for immunosuppression and could lead to overtreatment.15, 16, 17 A threshold GEP score of ≥ 34 for patients > 6 months post-HT has a sensitivity of 51.1%, a specificity of 63.4%, a positive predictive value of 2.82%, and a of 98.5%.18 In the multicentre Donor-Derived Cell-Free DNA-Outcomes AlloMap Registry (D-OAR) study, 740 HT recipients had biopsy samples paired with a quantified dd-cfDNA test, which showed a negative predictive value of 97.1% using a threshold of 0.20%.8,19 Therefore, noninvasive surveillance provides a more objective way to exclude rejection to further reduce immunosuppression.2,3,8,14,20

In our cohort, 4 patients underwent EMB for discordant noninvasive screening with positive dd-cfDNA testing. None of these patients had clinically significant rejection (either ACR or AMR) requiring immunosuppression change, hospital admission, or further intervention. Although these are “false-positive,” the increased levels of dd-cfDNA may be the result of other graft or endothelial injury that we are unable to detect in this study due to the limited follow-up time.8,14,20,21 Other studies using a combination of noninvasive surveillance methods in patients over 6 months posttransplant were able to avoid the need for EMB in many more patients using combination dd-cfDNA and GEP testing, rather than isolated GEP screening (83.9% vs 72.2%).22

In this study, nearly a third of tests were discordant with a positive GEP test and a negative dd-cfDNA test. The GEP test has several limitations that can be associated with a false-positive test, leading to a limited positive predictive value for cellular rejection. We suspect that several false-positive GEP results were associated with viral infection, including cytomegalovirus (CMV), which can cause elevated levels on a GEP test, with normal dd-cfDNA test results.6,7,12 In our cohort, 5 patients had prior CMV infection, and none of the patients had active CMV. Our group has shown that risk of CMV infection is higher at increased prednisone dose and for female recipients.12 Patients with viral infections were more likely to have elevated GEP scores, although these scores remained below the threshold for rejection screening.12 A similar-sized, single-centre trial of 37 HT recipients greater than 1 year post-HT had 6 patients who required EMB after elevation in either GEP or dd-cfDNA test levels.23 In this study, 61% of patients remained on prednisone therapy after 1 year. In the patients with elevated dd-cfDNA levels, 2 patients had cardiac allograft vasculopathy, and one had CMV infection, indicating the importance of screening for alternative conditions that may be causing graft injury while using dd-cfDNA testing as a noninvasive surveillance method in patients at a later time point posttransplant. We did not find any significant association between the COVID-19 vaccination and GEP scores, which we predicted may be associated with elevated GEP scores due to the immune response caused by mRNA vaccines. However, our cohort included only 17 patients vaccinated at variable times before the noninvasive testing.

The cost effectiveness of biomarkers assessing for acute rejection has been previously evaluated in a simulation model comparing GEP to EMB in the US.24 The model accounted for the probability of complication rates and incorporated published utility estimates and direct medical costs. This analysis suggested that GEP was an economically dominant strategy compared to EMB, with an average per-patient cost-saving of $27,244 and a quality-adjusted life-year gain of 0.046 over the first 5 years.24 Although these cost-savings may be overestimated in a socialized healthcare system, our patient satisfaction survey reinforces the benefits by highlighting the reduction in anxiety and fear that comes with avoiding a biopsy via a routine blood test. In previous studies, GEP was found to improve patient satisfaction without increasing the risk of adverse outcomes.2,3 Our patients had SF-12 physical health component scores that were slightly below average, and mental health component scores slightly above average, compared with those in the US population, and were similar when compared to SF-12 scores found in GEP studies for rejection surveillance.2,3 Noninvasive rejection surveillance eliminates the preparation time, recovery time, and risk of an invasive procedure, which may impact the mental health of HT recipients. Patients had increased satisfaction with noninvasive testing compared with EMB. These findings are similar to the HT recipient satisfaction described by Pham et al. in the Invasive Monitoring Attenuation through Gene Expression (IMAGE) trial, in which a significant increase in satisfaction was found in the GEP group over time, and this difference in satisfaction for the GEP compared to EMB patients persisted throughout the study follow-up period.3 Similar findings occurred in the Early Invasive Monitoring Attenuation Through Gene Expression (EIMAGE) trial, in which patients had a median satisfaction score of 10 of 10, which was significantly increased compared with that in the EMB group at 1 year.2

The most important limitation in this study is the lack of long-term follow-up to ensure the safety of the reduction of immunosuppression based on noninvasive testing. Nevertheless, several studies have shown longer-term safety with a dd-cfDNA threshold of ≤ 0.15%, and we do not anticipate harm.8,14,19 Additionally, none of the patients managed by noninvasive testing had clinically significant rejection, allograft dysfunction, or hemodynamic deterioration within a median follow-up time of 3 months. Since completing the dd-cfDNA testing for this study, all patients have undergone further surveillance testing with repeat standard testing (biopsy or GEP). We are confident that none of the patients have had any evidence of significant rejection (ACR > grade 1R or any evidence of AMR). We also limited our patient population to those who were at least 6 months post-HT, as this is our current local practice for noninvasive testing, but GEP has validity evidence for use as early as 55 days post-HT, and dd-cfDNA levels stabilize after 28 days post-HT.2,3,8,14 Future studies should include patients at all eligible time points posttransplant. This study was part of a quality-improvement initiative and therefore used no randomization or control groups. In this type of design (open-label, prospective time series), the goal is not to demonstrate that a given intervention increases or reduces the risk of rejection; rather, we were aiming to show that despite the limitations in access to surveillance EMB, we were able to adhere to our institutional surveillance protocol without experiencing excess short-term morbidity.

Other limitations of this study include the small sample size and the low incidence of allograft rejection. None of our patients developed significant ACR or AMR during the study period, so we were not able to interpret these results or follow trends in noninvasive testing in assessment of patients with rejection. Based on our institutional transplant protocol, we require surveillance biopsies in all transplant recipients who undergo initiation of mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitor or a change in target levels. In our cohort, 45% of patients required a surveillance biopsy for significant changes in immunosuppression beyond 2 years after transplant, when a biopsy may not have been warranted. Although elimination of all EMBs in the short-term is unlikely, we showed that using noninvasive surveillance is possible to safely reduce the total burden of this procedure on local resources without increasing short-term adverse events during a global pandemic. Further prospective research to assess applicability of noninvasive rejection surveillance in a post-pandemic era is warranted.

In conclusion, this study is the first in Canada to assess the role for noninvasive rejection surveillance in personalizing titration of immunosuppression post-HT. Overall, noninvasive rejection surveillance was associated with increased satisfaction and reduced anxiety in HT recipients, while minimizing exposure for patients and providers during a global pandemic.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the following: the Peter Munk Centre for Excellence in Heart Function, Toronto General Hospital; the Ted Rogers Centre for Heart Research; and the Ajmera Transplant Centre, University Health Network, all in Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

Funding Sources

This study was supported by CareDx Inc., Brisbane, CA, with in-kind donations of HeartCare testing kits to provide dd-cfDNA and GEP testing for patients. E.R.-A. is partially funded by the Spanish Society of Cardiology (Magda Heras grant, SEC/MHE-MOV-INT 21/001).

Disclosures

This study was supported by CareDx Inc., Brisbane, CA, with in-kind donations of HeartCare testing kits to provide dd-cfDNA and GEP testing for patients. The authors have no other conflicts of interest to disclose.

Footnotes

Ethics Statement: The study was approved by the University Health Network Quality Improvement Review Committee with a waiver of consent from the research ethics board (QI 21-0420).

See page 486 for disclosure information.

To access the supplementary material accompanying this article, visit CJC Open at https://www.cjcopen.ca/ and at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cjco.2022.02.002.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Costanzo M.R., Costanzo M.R., Dipchand A., et al. The International Society of Heart and Lung Transplantation guidelines for the care of heart transplant recipients. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2010;29:914–956. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2010.05.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kobashigawa J., Patel J., Azarbal B., et al. Randomized pilot trial of gene expression profiling versus heart biopsy in the first year after heart transplant: early invasive monitoring attenuation through gene expression trial. Circ Heart Fail. 2015;8:557–564. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.114.001658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pham M.X., Teuteberg J.J., Kfoury A.G., et al. Gene-expression profiling for rejection surveillance after cardiac transplantation. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1890–1900. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0912965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baraldi-Junkins C., Levin H.R., Kasper E.K., et al. Complications of endomyocardial biopsy in heart transplant patients. J Heart Lung Transplant. 1993;12:63–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Slomovich S., Roth Z., Clerkin K., et al. Remote monitoring of heart transplant recipients during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2021;40:S26. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kanwar M.K., Khush K.K., Pinney S., et al. Impact of cytomegalovirus infection on gene expression profile in heart transplant recipients. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2021;40:101–107. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2020.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kanwar M., Pinney S., Shah P., Kobashigawa J. Correlation of longitudinal gene-expression profiling (GEP) score to cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection: results from the Outcomes Allomap Registry. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2020;39:S83–S84. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Khush K.K., Patel J., Pinney S., et al. Noninvasive detection of graft injury after heart transplant using donor-derived cell-free DNA: a prospective multicenter study. Am J Transplant. 2019;19:2889–2899. doi: 10.1111/ajt.15339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Henricksen E.J., Purewal S., Moayedi Y., et al. Combining donor derived cell-free DNA and gene expression profiling for non-invasive surveillance after heart transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2021;40:S43. doi: 10.1111/ctr.14699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ware J., Kosinski M., Keller S.D. A 12-item short-form health survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care. 1996;34:220–233. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199603000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miles M., Huberman A., Saldaña J. 3rd ed. SAGE; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2014. Qualitative Data Analysis: A Methods Sourcebook. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moayedi Y., Gomez C.A., Fan C.P.S., et al. Infectious complications after heart transplantation in patients screened with gene expression profiling. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2019;38:611–618. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2019.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moayedi Y., Fan C.P.S., Tremblay-Gravel M., et al. Risk factors for early development of cardiac allograft vasculopathy by intravascular ultrasound. Clin Transplant. 2020;34 doi: 10.1111/ctr.14098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sean Agbor-Enoh, Shah P., Tunc I., et al. Cell-free DNA to detect heart allograft acute rejection. Circulation. 2021;143:1184–1197. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.049098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marboe C.C., Billingham M., Eisen H., et al. Nodular endocardial infiltrates (quilty lesions) cause significant variability in diagnosis of ISHLT grade 2 and 3A rejection in cardiac allograft recipients. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2005;24:S219–S226. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2005.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Crespo-Leiro M.G., Zuckermann A., Bara C., et al. Concordance among pathologists in the second Cardiac Allograft Rejection Gene Expression Observational Study (CARGO II) Transplantation. 2012;94:1172–1177. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e31826e19e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Crespo-Leiro M.G., Stypmann J., Schulz U., et al. Clinical usefulness of gene-expression profile to rule out acute rejection after heart transplantation: CARGO II. Eur Heart J. 2016;37:2591–2601. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moayedi Y., Foroutan F., Miller R.J.H., et al. Risk evaluation using gene expression screening to monitor for acute cellular rejection in heart transplant recipients. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2019;38:51–58. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2018.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Khush K.K. Clinical utility of donor-derived cell-free DNA testing in cardiac transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2021;40:397–404. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2021.01.1564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Richmond M.E., Zangwill S.D., Kindel S.J., et al. Donor fraction cell-free DNA and rejection in adult and pediatric heart transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2020;39:454–463. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2019.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Holzhauser L., Clerkin K.J., Fujino T., et al. Donor-derived cell-free DNA is associated with cardiac allograft vasculopathy. Clin Transplant. 2021;35 doi: 10.1111/ctr.14206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gondi K.T., Kao A., Linard J., et al. Single-center utilization of donor-derived cell-free DNA testing in the management of heart transplant patients. Clin Transplant. 2021;35 doi: 10.1111/ctr.14258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kewcharoen J., Kim J., Cummings M.B., et al. Initiation of noninvasive surveillance for allograft rejection in heart transplant patients > 1 year after transplant. Clin Transplant. 2022;36 doi: 10.1111/ctr.14548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hollander Z., Mohammadi T.H., Assadian S., et al. Cost-effectiveness of a blood-based biomarker compared to endomyocardial biopsy for the diagnosis of acute allograft rejection. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2016;35:S53. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.