Abstract

Optical control of the spin degree of freedom is often desired in application of the spin technology. Here we report spin-rotational excitations observed through inelastic light scattering of the hexagonal LuMnO3 in the antiferromagnetically (AFM) ordered state. We propose a model based on the spin–spin interaction Hamiltonian associated with the spin rotation of the Mn ions, and find that the spin rotations are angularly quantized by 60°, 120°, and 180°. Angular quantization is considered to be a consequence of the symmetry of the triangular lattice of the Mn-ion plane in the hexagonal LuMnO3. These angularly-quantized spin excitations may be pictured as isolated flat bubbles in the sea of the ground state, which may lead to high-density information storage if applied to spin devices. Optically pumped and detected spin-excitation bubbles would bring about the advanced technology of optical control of the spin degree of freedom in multiferroic materials.

Subject terms: Nanoscience and technology, Physics

Introduction

Application of spin control is looking forward to expanding its horizon to unprecedented level of data processing and storage capability1,2. Understanding the spin–spin interaction in magnetic materials are important and required in order to control the spin degree of freedom in the materials. However, most investigations trying to discover the origin of magnetic properties have been encountered with mixed information of unknown origin, which make it hard to analyze the genuine response from the magnetic system under investigation.

Despite the aforementioned difficulty, magnetic technologies have been actively explored in various fields to overcome the practical issues with the RMnO3 (R = rare earths, Y, and Sc) which are well known materials possessing ferroelectric and antiferromagnetic (AFM) transitions simultaneously. This binary character has been investigated by several optical and magnetic techniques as well as theoretical studies because of its immense potential for application3–7. Most RMnO3 materials exhibit a new possibility of tuning the response of the electric parameters to a magnetic field and vice versa, due to strong coupling of electric and magnetic order parameters8–13.

The crystal structure of hexagonal RMnO3 in P63cm space group leads to split the 3d energy levels of Mn3+-ions, due to change in the crystal field symmetry below the Curie–Wiess temperature TC (> 700 K)14–17. A Mn3+-ion has four electrons in 3d orbital (total S = 2). When a proper energy is supplied to the system, one of the electrons in / levels can be excited to the level, called Mn d–d transition11,16–18.

The Mn3+-ions are placed at position of the triangular lattice in a xy plane in paramagnetic phase. However, below Néel temperature TN (< 100 K), they move out of the ideal site due to Mn trimerization15,19–21, giving rise to two different spin–spin interaction integrals, intra-trimer interaction J1 and inter-trimer interaction J2.

Raman spectroscopy is based on the inelastic scattering related to electronic transitions in a material. Raman selection rule can help establish the excitations of the magnetic origin with high resolution22,23. Previous Raman studies show that the spin excitations strongly correlated with a particular electronic transition are observed in hexagonal RMnO3 below the TN24–28. Spin excitations of relatively high energy (~ 0.1 eV) are optically excited in the hexagonal RMnO3 system through the resonance with the Mn d–d transition24,28–30. These are not phonons at the zone boundaries that could fold in due to structural or magnetic ordering.

LuMnO3 is of the popular hexagonal manganite family crystalized in the P63cm group below TN6,14,20,31. Unlike other rare-earth hexagonal RMnO3, only Mn3+-ion has spins in hexagonal LuMnO310,32, and the spin excitations in the Mn-ions can be well separated without screening or overlapped effects by other than Mn-ion spins. Diverse articles have been reported regarding this material for the latest several years, focusing on the ensemble of the lattice constant, crystal structure, spin structure, phonon, magnon and spin exchange integrals9,12,13,15.

In this study, we present a microscopic explanation for the origin of spin excitations based on a simple spin-spin interaction Hamiltonian in hexagonal LuMnO3 system. We propose a model associated with the spin rotation of the Mn ions in the symmetry of the triangular lattice with the AFM ordering. Our model can explain the spin excitation peaks observed in LuMnO3 within the framework of the spin-spin interaction in the Mn-trimer network below TN.

Results

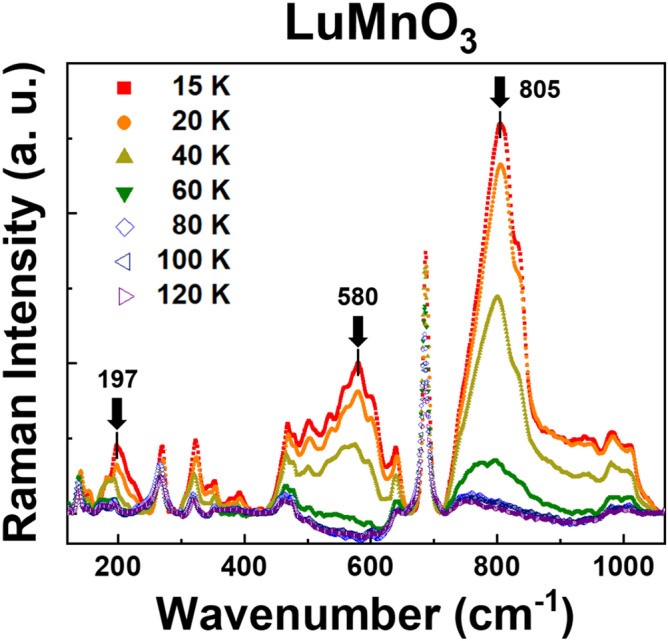

Figure 1 shows temperature-dependent Raman spectra of the hexagonal LuMnO3 single crystal in cross polarization scattering geometry from 120 to 1050 cm−1 range as a function of temperature. All the spectra were normalized by the intensity of the A1 phonon at ~ 680 cm−1. The A1 phonon should be forbidden in the cross polarization, except in the resonance condition. Other A1 (~ 266, 475 cm−1), E1 (~ 640 cm−1), and E2 (~ 318, 350, 461 cm−1) phonon modes observed in the spectra are consistent with previous results for LuMnO312. Besides these phonons, several broad peaks (~ 197, 580, 805 cm−1) are prominent at low temperatures. These broad peaks disappear above a critical temperature ~ 80 K. (See the Supplementary Information.) As in various hexagonal RMnO3, AFM spin ordering appears under ~ 100 K, and the TN values for LuMnO3 suggested by previous papers are consistent with the critical temperature ~ 80 K24,33,34. This strongly suggests that these broad peaks are in harmony with the AFM spin ordering in LuMnO3. In the sense that the peaks in the Raman scattering spectra measure the energy difference between the ground state and the excited state, it is reasonable to assume that the broad peaks represent the energy difference between the ground state and several excited states of the AFM spin ordering. The peak at 805 cm−1 may be considered as the spin-flip excitation energy for the Mn3+ ions in one triangle of the lattice (trimer) in LuMnO3 just as the 760 cm−1 peak in HoMnO3 is claimed to be due to the spin-flip excitation28. What about the origin of the other broad peaks at lower wavenumbers? In order to answer the question, we first need to look for the physical parameters from the relationship between the measured Raman peak at 805 cm−1 and the Hamiltonian for the spin-flip excitation of the Mn3+ ions in the trimer.

Figure 1.

Temperature dependence of Raman spectra of hexagonal LuMnO3 single crystal in the cross scattering configuration. Several broad peaks (~ 197, 580, 805 cm−1) are prominent at low temperatures, and disappear above 80 K (~ TN).

The spin excitation peaks in hexagonal RMnO3 have been observed by red lasers only24,29,30. The optical conductivity measurements on hexagonal RMnO3 provide convincing evidence that the Mn d–d transition take place 1.5–1.8 eV at room temperature11,16–18. In LuMnO3, Mn d–d transition would occur around 1.615 eV at 300 K, and the Mn d–d transition peak blue shifts about 0.15 eV at 10 K16. Red excitation lasers of 620–700 nm wavelength supply the energies corresponding to 1.77–2 eV, close to the energies of Mn d–d transition of LuMnO3 at 10 K. Many Raman scattering studies on hexagonal RMnO3 system support our interpretation of resonance with Mn d–d transition well24,29,30. The resonance Raman scattering is specific only to the Mn d–d transition, so that the spin excitations observed by the red lasers are independent of the disturbance from the excitations of the R ions. Therefore, the resonance Raman scattering would open a new opportunity to study the magnetic properties associated with the Mn ions selectively in hexagonal RMnO3 system.

The resonance effect with the Mn d–d transition further supports that these broad peaks observed in LuMnO3 below TN may be from the excitation of the Mn-ions. But are they due to the excitation in the spin structure of Mn-ions? Let us consider possible excited Mn3+-ion spin configurations in triangular lattice within the AFM ordering symmetry. Our aim is to calculate the excitation energy , and match with the energies of the broad peaks observed in the Raman spectra.

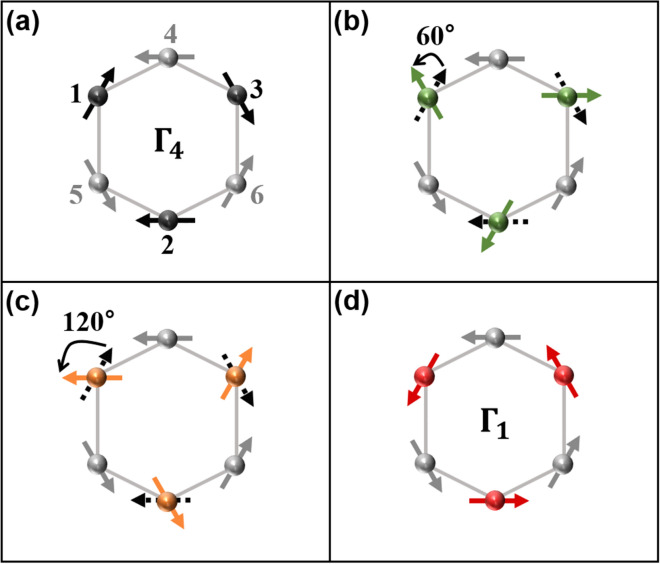

Mn d–d transition would induce a transient excited state of different spin symmetry. The new transient spin-ordered state should be consistent with the AFM structure of the P63cm space group. Spin structures in this manuscript are described by unidimensional representations as in diverse literatures19,21,31. Among the representations, is the most plausible candidate for the ground state of LuMnO3 as displayed in Fig. 2a20,34,35. The Mn-ion spins are arranged on a trimer with counterclockwise configuration in the plane (gray solid spheres), while those are arranged with clockwise configuration in the plane (black solid spheres). Layered MnO5 bipyramids are separated far enough to ignore the interaction of the Mn-ions between the planes, so the main concern would be interactions in one xy plane32,35. In this manuscript, we will assume that three Mn ions of a trimer in the plane only are excited by the resonant light.

Figure 2.

Several AFM spin configurations of hexagonal LuMnO3 single crystal. Mn-ions are indicated by solid spheres: gray spheres (number 4, 5, 6) are located in the plane and black or colored ones (number 1, 2, 3) are in the plane. Each arrow overlapped with the sphere expresses the spin direction of a Mn3+-ion (S = 2). We assume that colored spheres only are excited by the incident light. (a) The spin structure in the ground state. (b) Three spins (1, 2, 3) rotated counterclockwise by 60° (green arrows), or (c) by 120° (orange arrows). (d) Three spins (1, 2, 3) are flipped from the structure, resulting in the spin structure locally (red arrows).

Raman selection rule is resulted from the conservation of total angular momentum, . Here, is total angular momentum, is orbital angular momentum, and is spin angular momentum. Raman scattering has a two-photon process which should satisfy . As was explained above, resonance Raman scattering in hexagonal RMnO3 is linked with Mn d–d transition, so would remain unchanged, which requires . However, the probability of approaching while maintaining the AFM spin ordering would be low, due to the frustration condition imposed by the triangular lattice. As a result, is the most probable transition allowed within the AFM ordering as well as Raman selection rule. It would be possible to satisfy both conditions if all the three spins in one trimer rotate simultaneously by the same angle in the same direction. The symmetry of the triangular lattice permits only certain angles of rotation of the spins, namely, 60°, 120°, and 180°. These three rotations are illustrated in Fig. 2b–d. Details of argument on the angular quantization of the spin-rotational excitation are given in the Supplementary Information. Number 1, 2, 3 spins are rotated counterclockwise from the spin structure of symmetry shown in Fig. 2a, by 60° (Fig. 2b, green arrows), by 120° (Fig. 2c, orange arrows), and by 180° (Fig. 2d, red arrows), after excitation. Especially if all the three spins in one trimer are rotated 180° (Fig. 2d), which is identical with the flipping of all three spins, the symmetry of the spin ordering would change from to representation locally. In analogy, these may be regarded as the bubbles in the sea.

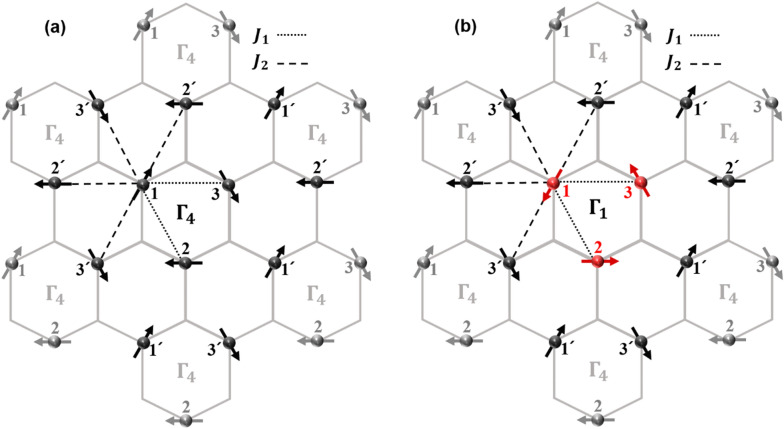

A simple Hamiltonian is suggested below to address the spin excitations involving rotation of the spins in hexagonal LuMnO3 system. The Hamiltonian includes two terms for the spin interactions; first term is the spin–spin interaction between the Mn-ions within a trimer with spin exchange integral (intra-triangular interaction), and second is that between the Mn-ions in neighboring triangles with (inter-triangular interaction). Figure 3 shows a concept of the model (Fig. 3a) in the ground state () and that (Fig. 3b) in one of the excited states (). There are six other trimers () around a norm trimer. Below TN, Mn trimerization contracting in the Mn-ion xy plane is found in LuMnO3, which makes it possible to distinguish and 15,19–21. In Fig. 3a, number 1 spin has two nearest neighbors (number 2 and 3) connected with dotted line (intra-triangular interaction ) and four next nearest neighbors (number 2′ and number 3′) connected with dashed line (inter-triangular interaction ). Likewise, each of number 2 spin and number 3 spin has also two and four interactions. Considering double counting, the Hamiltonian should be as follows;

| 1 |

where is the Mn3+-ion spin in one trimer, and is that in six neighboring trimers.

Figure 3.

A trimer composed of three Mn-ions (center), and its six neighbors in the plane in hexagonal LuMnO3 single crystal. Below TN, each trimer has two kinds of spin exchange integral: Dotted lines (nearest neighbor) indicate spin exchange integral , and dashed lines (next nearest neighbor) indicate spin exchange integral . (a) Every trimer has spin structure in the ground state. (b) Norm trimer has the spin structure locally after the spin-flip excitation, while its six neighbors remain in the spin structure.

The largest energy difference from ground state is derived from the Hamiltonian when the number 1, 2, 3 spins are rotated 180 degrees, namely, three-spin flipping. Additionally, other notable energy values are corresponding to rotation of the spins by 60° and 120°, and they are listed in Table 1. First, it suggests energy differences, , calculated by the Eq. (1). When the three spins in a trimer are rotated by the same angle simultaneously, there is no cost in the energy related to the stronger spin–spin interaction . Thus is determined by the weaker interaction only. Calculation based on the model is performed taking total S = 2 of a Mn3+-ion and assuming the excitation energy of the three-spin flipping is corresponding to the broad peak at ~ 805 cm−1 in Fig. 128. From our model, we could obtain the value of meV, which is in reasonable agreement with various researches dealing with hexagonal LuMnO320,33. It is notable that the excitation energies due to three-spin rotation by 60° and 120° precisely describe the broad peaks at 197 cm−1 and 580 cm−1 in Fig. 1, respectively.

Table 1.

Excitation energy values calculated from the model Hamiltonian in the text corresponding to the rotation angles of the three Mn-spins in a trimer in LuMnO3 single crystal.

| Rotation angle | Model calculation | Experimental data | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (meV) | (cm−1) | (meV) | (cm−1) | ||

| 24.95 | 201.3 | 24.43 | 197 | ||

| 74.85 | 603.7 | 71.91 | 580 | ||

| 99.80 | 804.9 | 99.81 | 805 | ||

In the model, and meV (Park, J. et al., Oh, J. et al.) are assumed.

Supplementary Figs. 2a, c, e, and g clearly show that spin rotations of a Mn-ion trimer by 0°, 60°, 120°, and 180° preserve the triangular symmetry by sustaining 30° or 60° angles between the spin directions. On the other hand, spin rotations by other angles, for example, 30°, 90°, and 150° do not keep the triangular symmetry (Supplementary Figs. 2b, d, f). Consequently, only 60°, 120°, and 180° rotations of a trimer are allowed in the hexagonal crystal symmetry, and thus the spin excitation energies are quantized by the inherent triangular symmetry of the hexagonal LuMnO336.

The spin excitation by 60°, 120°, and 180° rotation is a local excitation in one isolated trimer, not in the entire plane. These spin-rotational excitation of one Mn-ion trimer is like isolated flat bubble in the ground state of the sea. The spin symmetry of the bubble is locally different from the symmetry of the background.

A three-dimensional cartoon of the collection spin-rotational excitation bubbles is presented in Fig. 4 to help understand the nature of the isolated spin excitations. The spin ground states are abundant enough to form the sea below TN. When a resonant light generating the Mn d–d transition is applied to a part of the sea, in-plane spin-rotational excitations would emerge with rotation angles of 60°, 120°, and 180°. These spin excitations are isolated from each other, and each isolated excitation could be considered as an isolated flat bubble in the sea as pictured in Fig. 4. 60° rotations are depicted as green bubbles, 120° and 180° rotations, orange and red bubbles, respectively. Angularly-quantized spin-rotational excitation constitutes an example of energy quantization by the symmetry allowance.

Figure 4.

A visualization of the isolated spin-rotational excitations. Below TN, the Mn3+-ions are lying on each xy plane maintaining the spin structure. The spin states are excited by simultaneous rotation of the three spins in a trimer by 60° (green bubbles), 120° (orange bubbles), and by 180° (red bubbles) under the resonant light. The symmetry of the triangular lattice allows only these three rotations in hexagonal LuMnO3.

Discussion

We suggest a model based on a spin–spin interaction Hamiltonian to explain the spin excitation peaks observed in the Raman spectra of hexagonal LuMnO3 in the cross configuration below TN. Broad Raman peaks of hexagonal LuMnO3 below TN are excited through the resonance with the Mn d–d transition by the incident red laser (~ 1.85 eV). Our model for the spin excitation suggests simultaneous rotation of the spins of the in-plane Mn3+-ions to account for the energies of the Raman peaks. The model should meet several conditions: the Raman selection rule, preservation of the spin symmetry associated with the triangular lattice while maintaining the AFM spin ordering. A simple calculation is carried out to compare the model with our experimental Raman data. We could get a microscopic value for next nearest neighbor, meV, which is consistent with the results from the neutron scattering ( meV33) and theoretical calculations ( meV20, 3 meV37). Based on the values obtained, values are calculated by the Hamiltonian Eq. (1), therefore, we could assign the broad peaks as the isolated spin excitations associated with the spin rotation by 60°, 120°, and 180°. The ground spin state and the three-spin-flipping state represent and configuration, respectively, with the energy difference of ~ 0.1 eV (corresponding to ~ 805 cm−1).

In this study, the spin excitation peaks of LuMnO3 observed in the Raman scattering are due to the excitations solely in the Mn spins through the resonance with the Mn d–d transition. Neutron scattering and magnetization measurements of RMnO3 (R = rare earths) on the other hand, are affected by the strong paramagnetic moment of the rare-earth ions, and the magnetic excitations by the Mn-ions are hard to differentiate from those related with the rare earths. That is, resonance Raman has a potential to differentiate the magnetic phase transition due to the Mn ions especially in hexagonal RMnO3 system with strong paramagnetic moment of rare earth R3+ ions other than Lu3+ ions. Raman spectroscopy resonant with Mn d–d transition suggests a good approach to study the spin ordering of the Mn ions in other hexagonal RMnO3.

All the spin excitation peaks observed in LuMnO3 below the Néel temperature by an inelastic light scattering are explained in terms of the Heisenberg spin–spin interaction Hamiltonian. We claim that the peaks at 197, 580, and 805 cm−1 are due to excitations by Mn-ion spins rotated by 60°, 120°, and 180°, respectively. The rotation angles are quantized by 60°, 120°, and 180°, which is a consequence of the symmetry of the triangular lattice. The spin excitations are isolated in each triangular lattice. The isolated spin excitations may lead to optical control of the spin degree of freedom in future.

Materials and methods

Hexagonal LuMnO3 single crystal was grown using the traveling floating zone method and characterized by magnetization, resistivity, and x-ray powder diffraction38. Platelet sample was cleaved perpendicular to the c axis. The sample area was with thickness. Helium-closed-cycle cryostat was used to control the temperature of the sample from 15 to 120 K in vacuum chamber. Raman scattering spectra were obtained by Horiba LabRam spectrometer coupled with a liquid-nitrogen-cooled CCD under cross configuration. Excitation light source was visible red laser which has continuous 671 nm (~ 1.85 eV) wavelength, with the power of 40 mW on the chamber window. Laser spot radius was about when using × 40 objective lens. The background is subtracted from the raw Raman spectra and Adjacent-Average smoothing is performed by window size 7, threshold 0.05 after the subtraction. Whole data are normalized by the A1 phonon (~ 680 cm−1) intensity and we considered temperature dependence of the A1 phonon12 for each temperature when normalizing the spectra.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

The measurements in this work were supported by Korea Basic Science Institute (National Research Facilities and Equipment Center) grant funded by the Ministry of Education (2020R 1A 6C 101B194). Part of this research was supported by Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education (2021R1A6A1A10039823). I. S. Y. acknowledges the financial support by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korean government (Grant No. 2017R1A2B2009309). The work at Rutgers University was supported by the DOE under Grant No. DOE: DE-FG02-07ER46382.

Author contributions

S.K. performed the experiments, carried out the analyses of data, and designed a model to explain the origin of the spin-excitation. S.K. and J.N. contributed to the experimental set-up and data processing. X.X. and S.-W.C. synthesized and characterized the crystals. I.-S.Y. conceived the project and supervised the research. S.K. and I.-S.Y. wrote the draft and revised the manuscript. All authors have discussed the results and reviewed the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-022-06394-2.

References

- 1.Lottermoser T, Lonkai T, Amann U, Hohlwein D, Ihringer J, Fiebig M. Magnetic phase control by an electric field. Nature. 2004;430:541–544. doi: 10.1038/nature02728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rovillain P, et al. Electric-field control of spin waves at room temperature in multiferroic BiFeO3. Nat. Mater. 2010;9:975–979. doi: 10.1038/nmat2899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yakel Jnr HL, Koehler WC, Bertaut EF, Forrat EF. On the crystal structure of the Manganese(III) trioxides of the heavy lanthanides and yttrium. Acta Crystallogr. A. 1963;16:957–962. doi: 10.1107/S0365110X63002589. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smolenskiĭ GA, Chupis IE. Ferroelectromagnets. Sov. Phys. Uspekhi. 1982;25:475–493. doi: 10.1070/pu1982v025n07abeh004570. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fiebig M, Pavlov VV, Pisarev RV. Second-harmonic generation as a tool for studying electronic and magnetic structures of crystals: review. J. Opt. Soc. Am. B Optic. Phys. 2005;22:96–118. doi: 10.1364/josab.22.000096. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang YT, Luo CW, Kobayashi T. Understanding multiferroic hexagonal manganites by static and ultrafast optical spectroscopy. Adv. Condens. Matter Phys. 2013;2013:1–13. doi: 10.1155/2013/104806. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mochizuki M, Nagaosa N. Theoretically predicted picosecond optical switching of spin chirality in multiferroics. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2010;105:147202. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.105.147202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pimenov A, et al. Possible evidence for electromagnons in multiferroic magnanites. Nat. Phys. 2006;2:97–100. doi: 10.1038/nphys212. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tomuta DG, Ramakrishnan S, Nieuwenhuys GJ, Mydosh JA. The magnetic susceptibility, specific heat and dielectric constant of hexagonal YMnO3, LuMnO3 and ScMnO3. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter. 2001;13:4543–4552. doi: 10.1088/0953-8984/13/20/315. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Petit S, et al. Spin phonon coupling in hexagonal multiferroic YMnO3. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2007;99:266604. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.99.266604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Choi WS, et al. Optical spectroscopic investigation on the coupling of electronic and magnetic structure in multiferroic hexagonal RMnO3(R = Gd, Tb, Dy, and Ho) thin films. Phys. Rev. B. 2008;78:054440. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.78.054440. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vermette J, et al. Raman study of the antiferromagnetic phase transitions in hexagonal YMnO3 and LuMnO3. J. Phys. Condens. Matter. 2010;22:356002. doi: 10.1088/0953-8984/22/35/356002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Basistyy R, et al. Infrared-active optical phonons and magnetic excitations in the hexagonal manganites RMnO3 (R= Ho, Er, Tm, Yb, and Lu) Phys. Rev. B. 2014;90:024307. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.90.024307. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fiebig M, et al. Determination of the magnetic symmetry of hexagonal manganites by second harmonic generation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2000;84:5620–5623. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.84.5620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee S, et al. Giant magneto-elastic coupling in multiferroic hexagonal manganites. Nature. 2008;451:805–808. doi: 10.1038/nature06507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Souchkov AB, et al. Exchange interaction effects on the optical properties of LuMnO3. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2003;91:027203. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.91.027203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Degenhardt C, Fiebig M, Fröhlich D, Lottermoser T, Pisarev RV. Nonlinear optical spectroscopy of electronic transitions in hexagonal manganites. Appl. Phys. B. 2001;73:139–144. doi: 10.1007/s003400100617. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kalashnikova AM, Pisarev RV. Electronic structure of hexagonal rare-earth manganites RMnO3. JETP Lett. 2003;78:143–147. doi: 10.1134/1.1618880. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fabrèges X, et al. Spin-lattice coupling, frustration, and magnetic order in multiferroic RMnO3. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2009;103:067204. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.103.067204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Park J, et al. Doping dependence of spin-lattice coupling and two-dimensional ordering in multiferroic hexagonal Y1−xLuxMnO3 (0 ≤ x ≤ 1) Phys. Rev. B. 2010;82:054428. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.82.054428. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sim H, Oh J, Jeong J, Le MD, Park J-G. Hexagonal RMnO3: a model system for two-dimensional triangular lattice antiferromagnets. Acta Crystallogr. B. 2016;72:3–19. doi: 10.1107/S2052520615022106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Devereaux TP, Hackl R. Inelastic light scattering from correlated electrons. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2007;79:175–233. doi: 10.1103/RevModPhys.79.175. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim K, et al. Suppression of magnetic ordering in XXZ-type antiferromagnetic monolayer NIPS3. Nat. Commun. 2019;10:1–9. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-08284-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen X-B, et al. Study of spin-ordering and spin-reorientation transitions in hexagonal manganites through Raman spectroscopy. Sci. Rep. 2015;5:13366. doi: 10.1038/srep13366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nguyen TMH, et al. Raman scattering studies of the magnetic ordering in hexagonal HoMnO3 thin films. J. Raman Spectrosc. 2010;41:983–988. doi: 10.1002/jrs.2531. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nguyen TMH, et al. Raman scattering studies of hexagonal rare-earth RMnO3 (R = Tb, Dy, Ho, Er) thin films. J. Raman Spectrosc. 2011;42:1774–1779. doi: 10.1002/jrs.2925. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nguyen TMH, et al. Correlation between magnon and magnetic symmetries of hexagonal RMnO3 (R = Er, Ho, Lu) J. Mol. Struct. 2016;1124:103–109. doi: 10.1016/j.molstruc.2016.03.043. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nam, J. -Y. et al, Localized spin‐flip excitations in hexagonal HoMnO3. J. Raman Spectrosc.. 10.1002/jrs.5969 (2020).

- 29.Chen X-B, et al. Resonant A1 phonon and four-magnon Raman scattering in hexagonal HoMnO3 thin film. New J. Phys. 2010;12:073046. doi: 10.1088/1367-2630/12/7/073046. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen X-B, et al. Spin wave and spin flip in hexagonal LuMnO3 single crystal. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2017;110:122405. doi: 10.1063/1.4979037. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Solovyev IV, Valentyuk MV, Mazurenko VV. Magnetic structure of hexagonal YMnO3 and LuMnO3 from a microscopic point of view. Phys. Rev. B. 2012;86:054407. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.86.054407. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Oh J, et al. Magnon breakdown in a two dimensional triangular lattice Heisenberg antiferromagnet of multiferroic LuMnO3. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2013;111:257202. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.111.257202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lewtas HJ, et al. Magnetic excitations in multiferroic LuMnO3 studied by inelastic neutron scattering. Phys. Rev. B. 2010;82:184420. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.82.184420. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fu, Z. et al, Magnetic structures and magnetoelastic coupling of Fe-doped hexagonal manganites LuMn1−xFexO3 (0 ≤ x ≤ 0.3). Phys. Rev. B94, 125150 10.1103/PhysRevB.94.125150 (2016).

- 35.Katsufuji T, et al. Crystal structure and magnetic properties of hexagonal RMnO3 (R = Y, Lu, and Sc) and the effect of doping. Phys. Rev. B. 2002;66:134434. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.66.134434. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Choi YJ. Giant magnetic fluctuations ant the critical endpoint in insulating HoMnO3. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2013;110:157202. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.110.157202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Oh J, et al. Spontaneous decays of magneto-elastic excitations in non-collinear antiferromagnet (Y, Lu)MnO3. Nat. Commun. 2016;7:13146. doi: 10.1038/ncomms13146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lim D, et al. Coherent acoustic phonons in hexagonal manganite LuMnO3. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2003;83:4800–4802. doi: 10.1063/1.1630847. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.