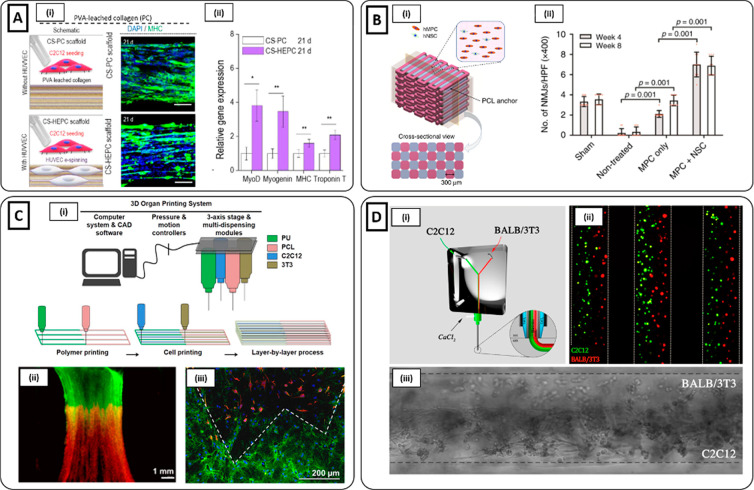

Figure 9.

Advanced hydrogel fiber-based methods for the fabrication of skeletal muscle tissue interfaces. (Ai) Schematic of C2C12-seeded alginate/PEO electrospun scaffold (CS-PC), C2C12-seeded on HUVEC-electrospun alginate/PEO scaffold (CS-HEPC), and corresponding fluorescent images of MHC (green) and nuclei (blue) on day 21. Enhanced MHC expression and (ii) relative myogenic gene expression was observed for C2C12/HUVEC scaffolds compared to those with C2C12-only (Reproduced with permission from ref (205). Copyright 2020 Elsevier). (Bi) Schematic of hMPC/hNSC-laden 3D bioprinted scaffold for the fabrication of neuronal/muscle interface. (ii) A higher number of NMJs was detected on hMPC/hNSC-laden 3D bioprinted scaffold (MPC+NSC) compared to hMPC-laden 3D bioprinted scaffold (MPC) after 8 weeks of implantation (Reproduced with permission from ref (144). Copyright 2020 The Authors, Springer Nature CCBY-NC-ND 4.0). (Ci) Schematic of the 3D integrated organ printing (IOP) system for the fabrication of MTU. (ii) Fluorescently labeled 3D bioprinted MTU constructs (green C2C12 myoblasts; red NIH 3T3 fibroblasts; yellow interface region). (iii) C2C12 myoblasts and NIH 3T3 fibroblasts expressed desmin (red) and collagen type I (green), respectively. At the interface region, cells created a pattern reliable with a native tissue interface (Reproduced with permission from ref (143). Copyright 2015 IOP Publishing). (Di) Multicellular 3D bioprinting through a Y-shaped microfluidic printing head. (ii) C2C12 myoblasts (green) and BALB/3T3 fibroblasts (red) were simultaneously extruded to obtain a Janus-like configuration which (iii) retained high compartmentalization after 5 days of culture (Reproduced with permission from ref (7). Copyright 2017 Elsevier CCBY-NC-ND 4.0).