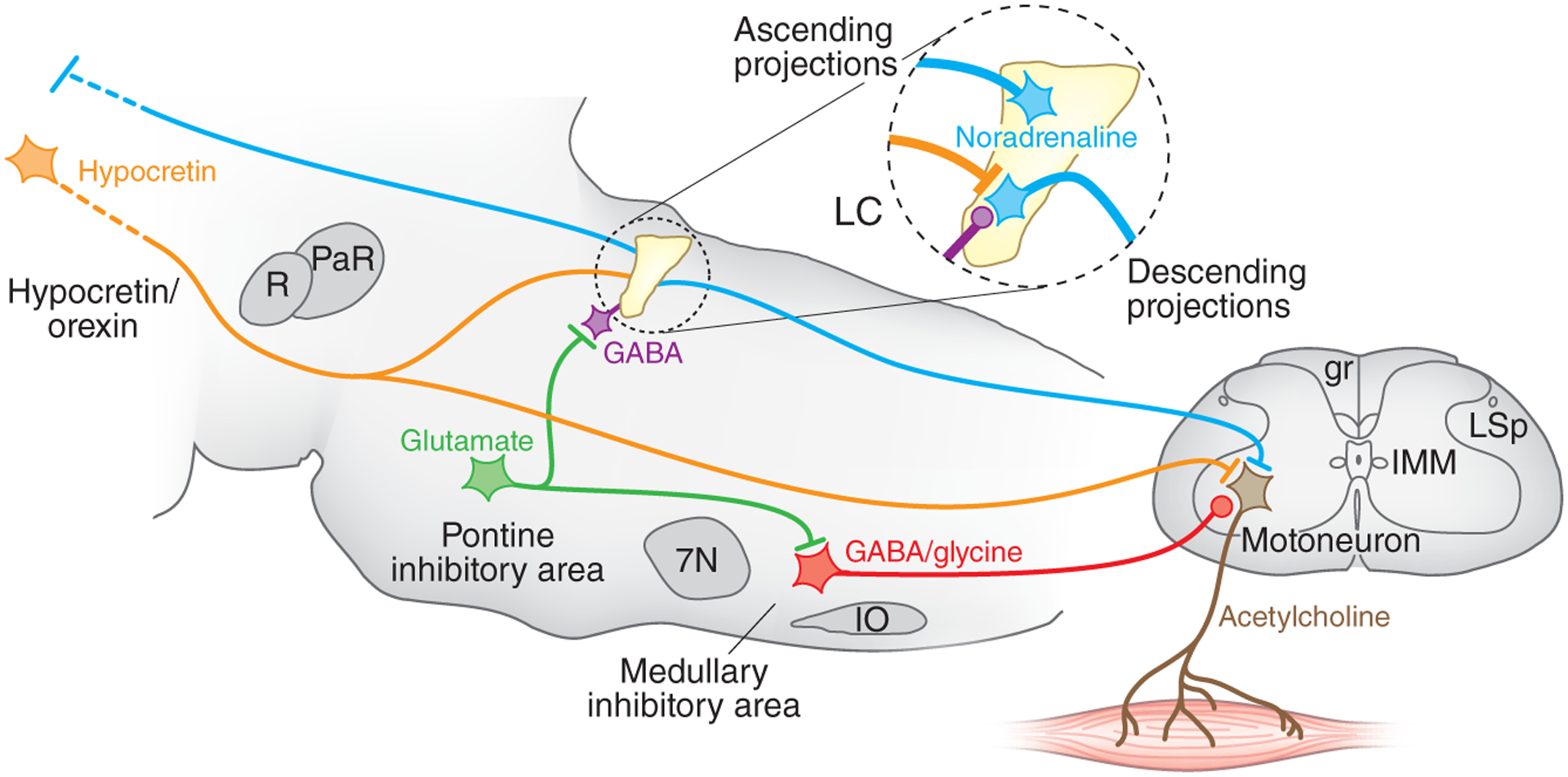

Figure 1.

The locus coeruleus and muscle tone regulation. Shown is a sagittal section of the brainstem modeling some important elements of the circuit regulating muscle tone. Circled region shows the inputs and outputs to the locus coeruleus, which contains noradrenergic cells. The locus coeruleus projects ascending axons to the forebrain, where it can increase alertness, and to spinal motoneurons, where it facilitates muscle tone. Locus coeruleus cells shut off before and during REM sleep and before and during cataplexy. Muscle tone is lost in REM sleep. It is also lost in cataplexy, but in cataplexy waking is maintained. The cessation of noradrenaline release disfacilitates muscle tone. Carter et al.2 found that depletion of noradrenaline by high-frequency stimulation also produces a loss of muscle tone. Hypocretin (orexin) neurons, located in the hypothalamus and inactive in sleep, excite both locus coeruleus and motoneurons. Loss of muscle tone in REM sleep and cataplexy results not only from disfacilitation but also from active inhibition by glycine and GABA. The glutamatergic cells in the pontine inhibitory region, which are selectively active in REM sleep, inhibit locus coeruleus neurons through a GABAergic interneuron and excite cells in the medullary inhibitory region, which directly or indirectly release GABA and glycine onto motoneurons, depicted at the L7 level. Lines at axon terminations indicate excitatory connections and circles indicate inhibitory connections. gr, gracile fasciculus; IMM, intermedio-medial nucleus; IO, inferior olive; LC, locus coeruleus; LSp, lateral spinal nucleus; PaR, pararubral nucleus; R, red nucleus; 7N, seventh nerve nucleus.