Abstract

Objective:

Patients with multiple medical conditions and complex social issues are at risk for high utilization and poor outcomes. The Connecting Provider to Home program deployed teams of a social worker and a community health worker (CHW) to support patients with social issues and access to primary care. Our objectives were to examine the impact of the program on utilization and satisfaction with care among older adults with complex social and medical issues.

Design:

Retrospective quasi-experimental observational study with matched comparator group.

Setting:

Community-based program in Southern California.

Participants:

Four hundred twenty community dwelling adults.

Intervention:

Community-based healthcare program delivered by a social worker and CHW team for older adults with complex medical and social needs.

Measurements:

Acute hospitalization and emergency department (ED) visits in the 12 months preceding and following enrollment in the pilot program. A “difference-in-difference” analysis using a matched comparator group was conducted. Comparator group data of patients receiving usual care were obtained. Surveys were conducted to assess patient satisfaction and experiences with the program.

Results:

The mean age of patients was 74 years, and the program demonstrated statistically significant reductions in acute hospitalizations and ED use compared with 700 comparator patients. Pre/post-acute hospitalizations and ED visits were reduced in the intervention group. The average per patient per year reduction in acute hospitalizations was −0.66, whereas the average per patient reduction in ED use was −0.57. Patients enrolled in the program reported high levels of satisfaction and rated the program favorably.

Conclusions:

A care model with a social worker and CHW can be linked to primary care to address patient social needs and potentially reduce utilization of healthcare services and enhance patient experiences with care.

Keywords: community health worker, community-based care, social determinants of health, social worker

INTRODUCTION

Older adults with multiple medical conditions and complex social issues are at risk for avoidable hospitalizations and emergency department (ED) visits and poor self-management of chronic conditions.1–3 When the physician has limited knowledge of the patient’s condition and functioning at home, it may result in misinformed treatment plans, goals of care not being met, and unnecessary healthcare utilization. An effective way to improve health outcomes for older adults with complex medical and social needs is by implementing partnered and team-based models of care4,5 that include social workers6 and community health workers (CHWs).7 Research has shown the efficacy of CHWs in successfully improving patient outcomes, and the national academies of medicine recommend expanded roles for them in chronic disease care.8 Social work services have also demonstrated positive outcomes, particularly in mental health and substance use, for vulnerable older adult populations who are often disadvantaged by multiple social determinants of health.6,9

CHWs often have a connection to the community served and deliver interventions directly in the patient’s home.8,10 CHWs have been shown to be effective at addressing the social determinants of health that contribute to poor clinical outcomes and are utilized in the team-based care of chronic conditions.8,11–17 Furthermore, CHWs are able to address socioeconomic issues by incorporating a culturally and linguistically adjusted intervention approach that may include families or care-givers.8,15,18 A team that incorporates a CHW and a social worker6,19 may be well positioned for delivering interventions to older adults with chronic conditions20–26 in the setting of complex social needs.7,11,16,27–30 There is evidence that CHW interventions in different healthcare settings are associated with reductions in preventable hospitalizations and overall cost of care.8,11,12,16,28,31

New models of community-based care for vulnerable older adults need to incorporate culturally and linguistically appropriate care to help close costly disparities in care.32 There are 8.1 million racial and ethnic minority older adults in the United States, comprising 20.4% of the population aged 65 years and older.33 This number will continue to rise between now and 2030 with minority older adults projected to increase by approximately 125% compared with 54% for older non-Hispanic whites.34 Community-based models of care that incorporate community and social work participation present an opportunity to reduce preventable hospitalizations and overall cost of care in ethnically diverse communities.8,11,26,28

The Connecting Provider to Home pilot program is designed to improve health care for older adults by providing additional home and community-based care, co-management, and oversight to patients who are most in need, as determined by their primary care physicians (PCP) and/or medical group. The underlying assumption is that once social barriers are mitigated, potential medical care gaps will be addressed; patients’ overall quality of care will improve; treatment plans will be more person-centered, and patients will be more likely to understand and comply with their medical care regimens.35,36 The objectives of the pilot study were to reduce unnecessary utilization, enhance provider and patient satisfaction, and improve communication between the patient and the healthcare team by understanding and addressing the social needs of vulnerable older adults.

EVALUATION

Evaluation of study design

In this case study of the Connecting Provider to Home pilot program, we conducted a retrospective quasi-experimental observational study to evaluate its impact on utilization of ED visits and hospitalizations compared with similar patients in usual care. We also conducted survey interviews with a convenience sample of patients to evaluate the acceptability of the program. The evaluation was approved by the University of California Los Angeles Institutional Review Board.

Setting and participants

Participants enrolled in the Connecting Home to Provider pilot program (intervention group, n = 420) were patients receiving care in one of six SCAN provider partner medical groups in California. The distribution of participants across medical groups ranged from 11.1% to 26.2%. The pilot was launched in December 2015 with one medical group and sequentially expanded to include five additional medical group partners. Medical groups were urban/semirural and provided health care across six counties to a linguistically and culturally diverse population. The structure of the program is community and team-based and interdisciplinary and is composed of a social worker and a CHW who are integrated into community medical groups.

Patients were eligible for the pilot evaluation if they were referred by their medical group’s case management team (frequent hospitalizations or ED visits and needs were too intense for usual medical group or health plan case management), were community dwelling, and had an initial home assessment conducted by the social worker and CHW. Patients in nursing homes or assisted living facilities were not eligible for participation. There were no specific hospitalization or ED thresholds that triggered a patient referral or enrollment. Medical groups referred those with a need too intense for usual medical group case management and had failed to improve after usual case management. A separate random pool of patients (n = 4053) from the same provider partner medical groups was used to construct a comparator group of similar patients (n = 700) based on demographics (Table 1), but not enrolled in the pilot program. Propensity score (PS) matching was used to match groups based on available characteristics.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of Connecting Provider to Home participants and matched comparator usual care patients

| Characteristics | Connecting Provider to Home patients (n = 420) | Matched comparator usual care group (n = 700) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean years | 74.4 | 75.0 | 0.50 |

| Gender, % | 0.72 | ||

| Male | 41.0 | 40.0 | |

| Female | 58.6 | 60.0 | |

| Race/Ethnicity, % | |||

| Hispanic | 20.9 | 19.1 | 0.06 |

| White | 22.1 | 20.7 | |

| Black | 5.1 | 4.6 | |

| Asian | 1.1 | 1.2 | |

| Other | 50.8 | 54.3 | |

| Language, % | |||

| English | 45.3 | 44.2 | 0.12 |

| Spanish | 14.5 | 13.3 | |

| Asian language | 1.9 | 0.7 | |

| Other/unknown | 38.3 | 41.5 | |

| Medical group risk score | 2.67 | 2.56 | 0.40 |

| Diabetes mellitus, % | 53.1 | 47.2 | 0.14 |

| Vascular disease, % | 35.1 | 30.7 | 0.25 |

| Congestive heart failure, % | 27.7 | 25.8 | 0.59 |

| Pulmonary disease (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease), % | 24.2 | 26.0 | 0.65 |

| Cancer, % | 1.5 | 3.7 | 0.09 |

Home-based social intervention

The pilot sought to implement and test a home-based social program that tightly links a team of a social worker and a CHW to older adults in their homes and connects them to social services and supports primary care. The unique combination of the social worker and CHW allow the team to seamlessly first focus on nonmedical interventions (e.g., community referrals for food or housing, financial barriers, behavioral health, and caregiver support) to address social barriers to self-care and management and only then to shift focus to medical and disease-centric support.

A team consisting of one social worker and one CHW had a caseload of about 50 patients. Three medical groups had two teams, and the other three medical groups had one team. Four of the medical groups are full risk for all costs of care, and two are shared-risk groups that collaborated with SCAN.

Training

Initial training includes in office (e.g., identifying social issues, brief motivational interviewing, patient activation and goal setting, geriatric syndromes, and chronic disease self-care) and on the field training with supervision. To help with fidelity in training, audit tools are used. During the on the field training, dyad teams start with few cases and require frequent contact with supervisors and are audited and observed. After initial training, all the teams meet for 1 day per month to help with the uniformity and fidelity of the intervention approach across medical group partners. The care coordination manager and lead social worker lead the monthly training sessions where sample scenarios are discussed along with communication with clinical teams, finding community resources, basic familiarity with geriatric syndromes, chronic disease self-care, and motivational interviewing approaches. CHWs were bilingual and had a bachelor’s level education that allowed them to address the needs of vulnerable older adults with highly complex social challenges.

Interventions, workflows, and referrals

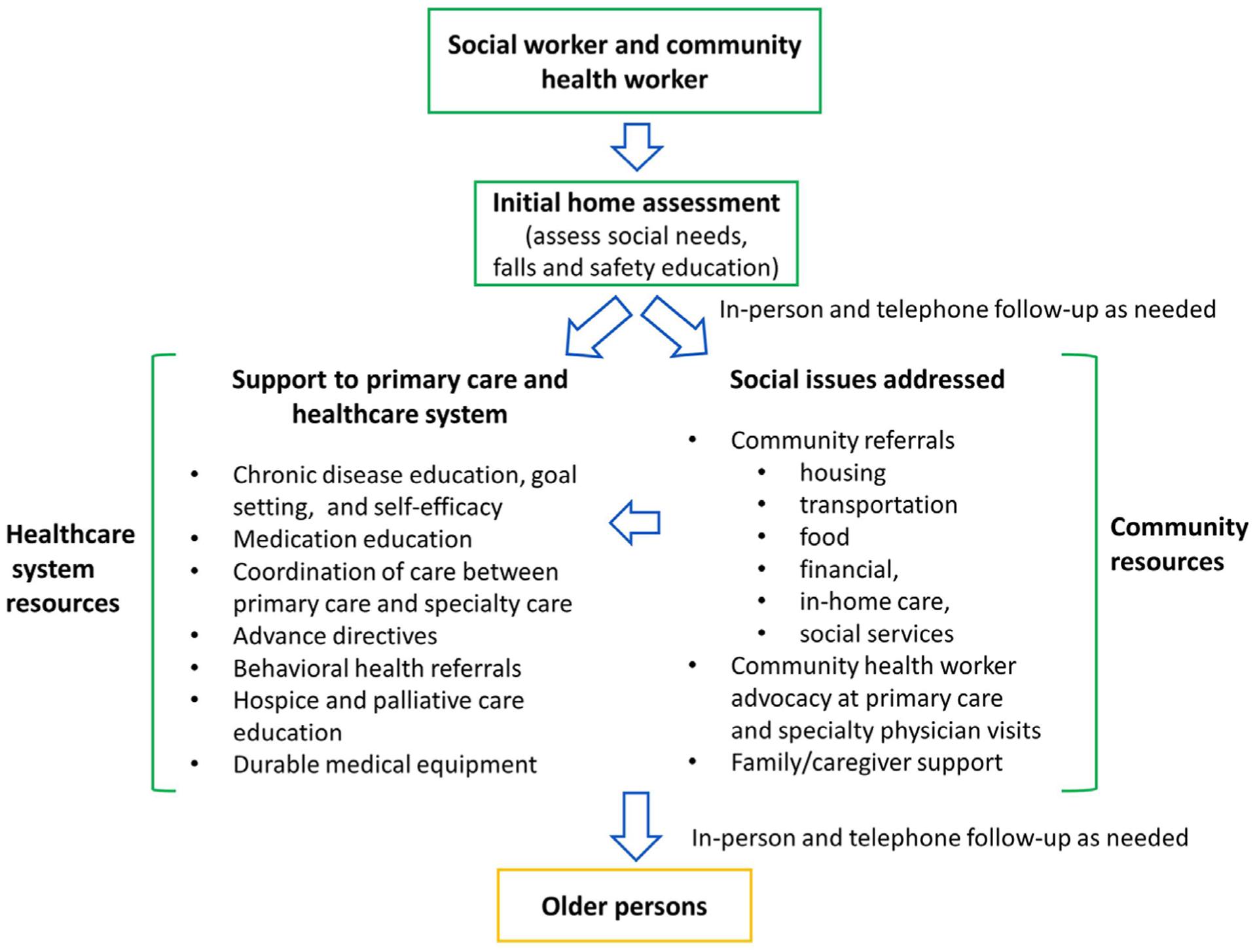

The social worker and CHW team supports patients by addressing social needs so that medical issues are addressed simultaneously or the patient could address them afterward. Once a referral is received from the medical group by the social worker, both the social worker and the CHW conduct an initial home visit with a standardized comprehensive assessment (Data S1) used to identify social needs and create a care plan and recommendations.37–40 After the initial home assessment, the team connects patients to community resources or social services (e.g., food, income support, housing, or transportation) in an individualized process that may take up to 6 months to address all of the social issues. While addressing social barriers, the team connects with the patient’s PCP to clarify issues or deliver support such as teaching patients to use inhalers, diabetes education, addressing barriers to polypharmacy and medication adherence, and facilitating the delivery and use of durable medical equipment, and provide other health services like assistance with referrals or accessing specialists (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Illustration of the Connecting Provider to Home model of care

In addition to patient social needs, the program supports the efforts of the PCP and healthcare care teams by conducting an initial in-home assessment; initiating a plan of care based on the patient’s social needs and the outcome of the in-home assessment; helping identify issues impacting patient health early, before they escalate; escalating issues that might otherwise get missed; participating in interdisciplinary care team meetings within partner medical groups and communicating findings and progress; identifying and helping remove barriers to care plan adherence and patient safety; attending scheduled doctors’ appointments (primary care and specialty physicians) as needed to improve patient self-efficacy during doctor visits and enhance understanding of treatment plan; and helping patients to adhere to care and treatment plans. The weekly interdisciplinary team meetings varied by medical group and included nursing and other medical group program representation (e.g., chronic disease management).

The most common interventions were referrals to community resources, care coordination among multiple providers, and addressing issues related to medications and polypharmacy (Figure 1). Interventions were documented in separate care management systems, and these data were not available due to limited data collection resources and heterogeneity in IT infrastructure across the medical groups.

Follow-up visits to the home depend on the individual needs of the patient and may include only the CHW. Once urgent social or medical issues are addressed, the CHW follows up through periodic telephone calls at least once a month. The teams used the telephone to communicate with the doctor’s office any urgent clinical needs identified during home assessments or follow-up calls. The primary care offices address urgent clinical issues. Enrollment in the pilot program was not limited to a prespecified amount of time.

Measures

Administrative, pilot program, and claims data were used to abstract participant measures and characteristics. Hospitalizations and ED use were the primary outcomes for the analysis. Elective hospitalizations were removed from outcome measures and analysis. Other patient-level measures included in the analysis were age, gender, language, race, ethnicity, medical group risk score, and diagnosis of chronic conditions (e.g., diabetes mellitus, vascular disease, cancer, and depression). Dummy variables for each partner medical group were constructed.

Participant surveys

A cross-sectional survey using a convenience sample of Connecting Provider to Home participants was administered among those that had at least 6 months enrolled in the program. The survey was conducted over the telephone and incorporated quality of care and communication items published in the literature.41

Analysis

The evaluation study design for utilization was a “difference-in-difference” (DID) analysis with a matched comparator group evaluation. We used a 12-month pre-time period and 12-month intervention time period for the analysis. Because the pilot program participants were referred for a home assessment at different time periods in time, the start (index dates) and end dates of the 12-month pre-time period and intervention windows vary by participant.42 The index date for each patient in the intervention group, which determines the start of the intervention, was determined by the date of the first home assessment conducted by the Connecting Provider to Home team.

The pseudo or quasi-intervention index date for the comparator group was chosen based on the median within network (provider partner group) intervention date. We conducted sensitivity analyses that included constructing a quasi-intervention index date for the comparator group that was the same as the first Connecting Provider to Home assessment date within each network.

We computed univariate frequencies and means for variables available for the evaluation, including the survey results. We performed cross-tabulations or stratifications by the evaluation study group for all variables. We also stratified outcome variables by pre/post-time periods and intervention versus comparator group assignments. Nearest-neighbor PS matching of 1:3 was used to identify a comparison group of patients/members with similar characteristics but not enrolled in the Connecting Provider to Home pilot program.43 We assessed comparability of means and proportions for individual baseline variables before and after PS matching using standardized differences considered to represent an acceptable level of balance between groups. To avoid potential bias from differential dropout across the two comparison groups, we censored both the Connecting Provider to Home pilot participant and their PS-matched non-participant at any point when we had data, indicating that either subject was no longer in care in the provider medical group.

We estimated (1) linear mixed effects models and (2) negative binomial mixed effects models both with a random effects, DID regression modeling that included a variable to denote “intervention” used to estimate monthly utilization rates before and after participants’ first Connecting Provider to Home assessment. The analysis models present incident rate ratios (IRRS) in Table 2 where the DID is presented as the interaction between time periods with the intervention group. The regression modeling included an interaction term for pre/post-time periods to account for secular trends and remaining differences in baseline utilization for the study groups.

TABLE 2.

Number and percent of persons in each group with no, one, or two or more hospitalizations and no, one, or two or more ED visits during one-year periods

| Variable | Connecting Provider to Home (n = 420) | Matched Comparator Usual Care (n = 700) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-time period | Post-time period | Difference | Pre-time period | Post-time period | Difference | |

| Hospitalizations | ||||||

| 0 | 231 (55.9%) | 281 (66.8%) | 50 (10.9%)* | 510 (72.9%) | 547 (78.2%) | 37 (5.3%) |

| 1 | 81 (19.6%) | 68 (16.2%) | −13 (3.2%) | 120 (17.2%) | 97 (13.8%) | −23 (3.4%) |

| 2 or more | 101 (24.5%) | 71 (17.0%) | −30 (7.5%) | 70 (9.9%) | 56 (8.0%) | −14 (1.9%) |

| ED visits | ||||||

| 0 | 183 (44.3%) | 238 (56.7) | 55 (12.3%)* | 441 (63.0%) | 454 (64.9) | 13 (1.9%) |

| 1 | 80 (19.4%) | 64 (15.2%) | −16 (4.2%) | 108 (15.5%) | 103 (14.7%) | −5 (0.8%) |

| 2 or more | 150 (36.3%) | 118 (28.1%) | −32 (8.2%) | 151 (21.5%) | 143 (20.4%) | −8 (1.1%) |

p < 0.05.

All quantitative statistical analyses were computed using SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC).

EVALUATION RESULTS

A total of 420 patients were enrolled and received services from the Connecting Provide to Home program during the study period. The demographics of the patients enrolled in the program are described in Table 1. Patients enrolled in the Connecting Provider to Home pilot program were 59% female, 45% with English as their primary language, and with an average age of 74 years. Over half of the patients in the pilot program had diabetes mellitus and less than a third had congestive heart failure. Characteristics for the comparator group are listed in Table 1.

Table 2 shows the number and percent of persons in each analysis group with no, one, or two or more hospitalizations and no, one, or two or more ED visits during one-year periods.

Participation in the Connecting Provider to Home program was associated with statistically significant reductions in hospitalizations and ED visits use when compared with the matched comparison group. In the DID analysis, pre/post-acute hospitalizations were reduced in the intervention group relative to the change over time observed in the comparator group. The average change in hospitalizations for the matched comparators was 0.04 compared with −0.66 in the intervention group. The average change in ED visits for the matched comparators was −0.17 compared with −0.57 in the intervention group.

Table 3 lists results where the adjusted IRRs for utilization of ED visits and hospitalizations among those who participated in the Connecting Provider to Home program compared with the usual care comparator group. Among participants in the Connecting Provider to Home program, there were statistically significant findings of a 33% lower relative risk of ED visits and an 18% lower relative risk of hospital utilization compared with the comparator group of patients.

TABLE 3.

IRRs for utilization among Connecting Provider to Home participants and matched comparator usual care patients

| Intervention by time periods | Hospitalizations estimate, IRR (SE) | p-value | Emergency department visits estimate, IRR (SE) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12 months | ||||

| Preintervention | Reference | Reference | ||

| Postintervention | 0.82 (0.73–0.91) | 0.006 | 0.67 (0.51–0.87) | 0.003 |

| 6 months | ||||

| Preintervention | Reference | Reference | ||

| Postintervention, 0–180 days | 0.92 (0.86–0.96) | 0.023 | 0.88 (0.80–0.96) | 0.009 |

| Postintervention, 181–365 days | 0.79 (0.74–0.85) | <0.001 | 0.36 (0.25–0.51) | <0.001 |

Note: Models were adjusted for age, gender, partner network/medical group, comorbidities, risk score, and baseline utilization 1 year before intervention. Difference in differences is presented as the interaction between time periods with the intervention group.

Abbreviations: IRR, adjusted incident rate ratio; SE, standard error.

Table 4 reports results of the patient satisfaction interview surveys among participants in the Connecting Provider to Home program. Participants reported high quality of communication with the social worker and CHW and rated the program highly globally. Patients believed the Connecting Provider to Home program was a key resource to improving their disease self-management skills and decreasing the use of the ED and the hospital. Patients viewed the CHW as complimentary to the social worker and as an integral asset that was accessible and was the first contact for enrolled patients. Most respondents rated their self-reported health as “good.” Patient participants rated the program favorably with a 4.8 global mean score (scale 1–5).

TABLE 4.

Satisfaction with Connecting Provider to Home program and team among patient participants (n = 168)

| Patient Satisfaction Survey Question | % |

|---|---|

| Explains things in a way that was easy to understand | |

| Always | 94 |

| Usually | 6 |

| Sometimes/never | 0 |

| Listen carefully | |

| Always | 94 |

| Usually | 6 |

| Sometimes/never | 0 |

| Show respect | |

| Always | 94 |

| Usually | 6 |

| Sometimes/never | 0 |

| Provided advice helpful in managing your health condition | |

| Always | 97 |

| Usually | 3 |

| Sometimes/never | 0 |

| Satisfied with the amount of time spent with you | |

| Always | 97 |

| Usually | 2 |

| Sometimes/never | 1 |

| Questions answered by the team | |

| Yes | 99 |

| No | 1 |

| Coordination of care with doctor’s office | |

| Yes | 91 |

| No | 9 |

| Prepared you for doctors’ appointments | |

| Always | 84 |

| Usually | 17 |

| Sometimes/never | 0 |

| Actively involved you in decision-making | |

| Always | 88 |

| Usually | 12 |

| Sometimes/never | 0 |

| Health status | |

| Excellent | 16 |

| Very good | 3 |

| Good | 49 |

| Fair | 32 |

| Poor | 0 |

| Recommend program | |

| Strongly agree | 88 |

| Agree | 14 |

| Disagree/strongly disagree | 0 |

| Improved my health | |

| Strongly agree | 75 |

| Agree | 25 |

| Disagree/strongly disagree | 0 |

| Global rating of program (1–5 scale), mean | 4.8 (range 3–5) |

DISCUSSION

In this study, we found that a home-based social worker and CHW intervention was associated with significant reductions in utilization rates for ED visits and hospitalizations in the 12 months after program enrollment as compared with the 12 months before enrollment. It is important to highlight that participants were vulnerable and ethnically diverse older adults with complex unmet social and medical needs. The reductions in utilization among the intervention group were statistically significant in analysis that controlled for potential confounders including preintervention utilization trends. The ability of the community health and social worker dyad to observe the patient in the home environment allows them to address social needs and then coordinate with the PCP in adapting treatment plans to optimize patient care. Likely mechanisms or reasons for these results could be due to additional primary care and specialty visits and urgent care visit. In addition, patients who participated in the pilot program self-reported high levels of satisfaction with the care, quality of communication with the team, and quality of care. Survey respondents highly rated the program high and reported that the CHW was someone they connected with and was easily accessible.

The Connecting Provider to Home program has similarities with other community and home-based models of care in that they focus on providing interdisciplinary care for older adults with very complex needs in the home.44–47 However, it expands the current models in important ways by utilizing an approach that includes and focuses on the community health and social worker dyad in high-intensity patient interventions over long periods of time in partnership with community PCPs in nonacademic settings. This program was conceived as a home-based “social” program, and the unique and combined professional skillsets of a social worker and a CHW provide optimal opportunities to focus on “upstream” interventions as opposed to after-the-fact interventions (downstream) in other programs.31

A critical question that remains unanswered is determining the optimal social worker-to-CHW ratio needed for scaling up the program to serve more patients. Although the pilot study was not designed to answer this question, SCAN took the approach of having teams that included a community health and social worker dyad to cover a specific medical group population and geographic region to better align the teams with the cultural and linguistic needs of a diverse population in California. Future research should also investigate sustainability46 and ways to effectively implement and sustain the program in different communities with varying healthcare systems that have different levels of capacity and experiences with community-based home care for older adults. A 12-month intervention analysis period was selected because regression to the mean is a concern in studies with patients having overwhelming complex health and social needs. Future directions could also include analyzing results after patients are no longer enrolled to see if regression to the mean occurs after disenrollment.

For partner medical groups, depending on the Medicare Advantage plan, the benefits of reducing ED visits and hospitalizations are intrinsic to the health plan in a risk-sharing contract or by a full-risk medical group.

Sustainability

Challenges to dissemination and sustainability in non-integrated settings include training the teams across different health plans and healthcare settings, varying IT infrastructure and systems across medical groups/practices, and a buy-in from leadership across medical groups or provider partners. As a result, it is crucial that financial alignment exists such that the return on investment accrues to the party making the investment. Future areas of study should include return on investments.

The experience with the pilot reaffirmed SCAN’s commitment to ameliorate the impact of the social determinants of heath on older adults. There are several successes of the pilot program related to sustainability and impact on the organization. After the pilot ended,

Two of the three full-risk medical groups self-funded and implemented the program with some variations specific to their medical group infrastructure.

SCAN also continued the program with a shared-risk medical group that participated in the pilot.

SCAN also added an additional shared-risk medical group.

SCAN collaborated with a new full-risk medical group to deliver multiple programs addressing social determinants and included a new Connecting Provider to Home team.

SCAN implemented two new programs that focus on (1) persons experiencing homelessness and (2) a CHW-only program that aims to mitigate barriers to the effective management of diabetes mellitus among older adults with diabetes mellitus, focusing primarily on Hispanic members.

SCAN continues to assist medical groups with training of CHWs.

Limitations

This pilot evaluation has limitations. The results may not be generalizable to other communities and healthcare settings, and this program was implemented in an ethnically and linguistically diverse community in California. All participants were community dwelling. The study design lacks randomization, and therefore, causal inferences should be interpreted with caution. Regression to the mean is also a possibility. Comparator group matching is a limitation, as we do not know that these two cohorts matched well in terms of social variables not measured. There is a possibility that we were not able to measure confounders at the patient and medical group level as we relied on administrative and Electronic Medical Record data to capture patient characteristics. Finally, long-term reductions in utilization cannot be inferred from the evaluation results.

Because the teams were embedded within the individual medical group provider partners, they recorded interventions in separate care management systems and these data were not available due to limited resources. The survey sample was nonrandom and responses are subject to bias due to socially desirable answers.

Our findings suggest that a home-based social determinants program that integrates social workers and CHWs successfully into community primary care teams to address patient social needs has the potential to reduce healthcare utilization and enhance satisfaction with care. Integrating community-based social workers and CHWs into primary and specialty care might result in positive outcomes for patients and providers.

Supplementary Material

Key Points

A home-based social determinants program can be successfully embedded in primary care

A social worker and a community health worker connected older adults to services and supported medical care

Why Does this Article Matter?

Addressing the social needs of older adults may prevent unnecessary utilization and enhance satisfaction with care.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to acknowledge Dr. Dan Osterweil MD, FACP, VP/Medical Director SCAN Health Plan, for his support and review of the draft manuscript. The authors are likewise grateful to all Connecting Provider to Home staff.

A summary of the findings was presented as an oral presentation in the 2019 Academy Health, 2019 Annual Research Meeting, Washington DC, June 2–4, 2019; as an oral presentation at the LeadingAge Annual Meeting & EXPO, Philadelphia, PA, October 28–31, 2018; as an oral presentation at the American Geriatrics Society Annual Scientific Meeting, Portland, OR, May 2–4, 2019; as an oral presentation at the Innovations in Chronic Care Management for Health Plans, Chicago, IL, May 20–21, 2019; as a poster presentation at the Gerontological Society of America Annual Scientific Meeting, Austin, TX, November 13–17, 2019; as a poster presentation at the North American Primary Care Research Group, Toronto, Ontario, Canada, November 16–20, 2019; and as a poster presentation at the IHI National Forum on Quality Improvement in Health Care, Orlando, FL, December 8–11, 2019.

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE

Drs. Moreno and Mangione received support for this work from the UCLA Resource Center for Minority Aging Research (NIA P30AG021684). Dr. Mangione also received support from the UCLA Clinical Translational Science Institute (NCATS UL1TR001881) and from the Barbara A. Levey and Gerald S. Levey Endowed Chair in Medicine.

SPONSOR’S ROLE

This work was supported by Independence at Home, a SCAN Community Service.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest.

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Additional supporting information may be found online in the Supporting Information section at the end of this article.

Data S1 Sample assessment form.

REFERENCES

- 1.Huang BY, Cornoni-Huntley J, Hays JC, Huntley RR, Galanos AN, Blazer DG. Impact of depressive symptoms on hospitalization risk in community-dwelling older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48(10):1279–1284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Salanitro AH, Hovater M, Hearld KR, et al. Symptom burden predicts hospitalization independent of comorbidity in community-dwelling older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(9): 1632–1637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maust DT, Kim HM, Chiang C, Langa KM, Kales HC. Predicting risk of potentially preventable hospitalization in older adults with dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67:2077–2084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bodenheimer T, Sinsky C. From triple to quadruple aim: care of the patient requires care of the provider. Ann Fam Med. 2014;12(6):573–576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ghorob A, Bodenheimer T. Sharing the care to improve access to primary care. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(21):1955–1957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Steketee G, Ross AM, Wachman MK. Health outcomes and costs of social work services: a systematic review. Am J Public Health. 2017;107(S3):S256–S266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Campos BM, Kieffer EC, Sinco B, Palmisano G, Spencer MS, Piatt GA. Effectiveness of a community health worker-led diabetes intervention among older and younger Latino participants: results from a randomized controlled trial. J Geriatrics. 2018;3(47). https://www.mdpi.com/2308-3417/3/3/47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pittman M, Sunderland A, Barnett K. Bringing Community Health Workers into the Mainstream of U.S. Health Care Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rizzo VM, J.M. R Cost-effectiveness of social work services inaging: an updated systematic review. Res Social Work Prac. 2016;26(6):653–667. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Malcarney MB, Pittman P, Quigley L, Horton K, Seiler N. The changing roles of community health workers. Health Serv Res. 2017;52(Suppl 1):360–382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim K, Choi JS, Choi E, et al. Effects of community-based health worker interventions to improve chronic disease management and care among vulnerable populations: a systematic review. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(4):e3–e28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kangovi S, Mitra N, Norton L, et al. Effect of community health worker support on clinical outcomes of low-income patients across primary care facilities: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(12):1635–1643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim KB, Kim MT, Lee HB, Nguyen T, Bone LR, Levine D. Community health workers versus nurses as counselors or case managers in a self-help diabetes management program. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(6):1052–1058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lohr AM, Ingram M, Nunez AV, Reinschmidt KM, Carvajal SC. Community-clinical linkages with community health workers in the United States: a scoping review. Health Promot Pract. 2018;19(3):349–360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Arvey SR, Fernandez ME. Identifying the core elements of effective community health worker programs: a research agenda. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(9):1633–1637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kangovi S, Mitra N, Grande D, Huo H, Smith RA, Long JA. Community health worker support for disadvantaged patients with multiple chronic diseases: a randomized clinical trial. Am J Public Health. 2017;107(10):1660–1667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kangovi S, Mitra N, Turr L, Huo H, Grande D, Long JA. A randomized controlled trial of a community health worker intervention in a population of patients with multiple chronicdiseases: study design and protocol. Contemp Clin Trials. 2017; 53:115–121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Basu S, Jack HE, Arabadjis SD, Phillips RS. Benchmarks for reducing emergency department visits and hospitalizations through community health workers integrated into primary care: a cost-benefit analysis. Med Care. 2017;55(2):140–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rizzo VM, Rowe JM. Studies of the cost-effectiveness of social work services in aging: a review of the literature. Res Social Work Prac. 2006;16(1):67–73. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Palmas W, March D, Darakjy S, et al. Community health worker interventions to improve glycemic control in people with diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(7):1004–1012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vaughan EM, Johnston CA, Cardenas VJ, Moreno JP, Foreyt JP. Integrating CHWs as part of the team leading diabetes group visits: a randomized controlled feasibility study. Diabetes Educ. 2017;43(6):589–599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lutes LD, Cummings DM, Littlewood K, Dinatale E, Hambidge B. A community health worker-delivered intervention in African American women with type 2 diabetes: a 12-month randomized trial. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2017;25(8): 1329–1335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carrasquillo O, Lebron C, Alonzo Y, Li H, Chang A, Kenya S. Effect of a community health worker intervention among Latinos with poorly controlled type 2 diabetes: the Miami healthy heart initiative randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(7):948–954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Spencer MS, Kieffer EC, Sinco B, et al. Outcomes at 18 months from a community health worker and peer leader diabetes self-management program for Latino adults. Diabetes Care. 2018;41 (7):1414–1422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Trump LJ, Mendenhall TJ. Community health workers in diabetes care: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Fam Syst Health. 2017;35(3):320–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jacob V, Chattopadhyay SK, Hopkins DP, et al. Economics of community health workers for chronic disease: findings from community guide systematic reviews. Am J Prev Med. 2019;56 (3):e95–e106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Balaban RB, Galbraith AA, Burns ME, Vialle-Valentin CE, Larochelle MR, Ross-Degnan D. A patient navigator intervention to reduce hospital readmissions among high-risk safetynet patients: a randomized controlled trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(7):907–915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jack HE, Arabadjis SD, Sun L, Sullivan EE, Phillips RS. Impact of community health workers on use of healthcare services in the United States: a systematic review. J Gen Intern Med. 2017; 32(3):325–344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mitchell P, Wynia M, Golden R, et al. Core Principles & Values of Effective Team-Based Health Care. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 30.American Geriatrics Society Expert Panel on the Care of Older Adults with Multimorbidity. Patient-centered care for older adults with multiple chronic conditions: a stepwise approach from the American Geriatrics Society: American Geriatrics Society Expert Panel on the Care of Older Adults with Multimorbidity. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(10):1957–1968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lin MP, Blanchfield BB, Kakoza RM, et al. ED-based care coordination reduces costs for frequent ED users. Am J Manag Care. 2017;23(12):762–766. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Waidmann T Estimating the Cost of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities. Washington, DC: The Urban Institute; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Federal Interagency Forum on Aging-Related Statistics. Older Americans 2012: Key Indicators of Well-Being. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Baron RM, Kenny D. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social Physchological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1986;51(6): 1173–1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cacchione PZ. Age-friendly health systems: the 4Ms framework. Clin Nurs Res. 2020;29(3):139–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Finkelstein A, Zhou A, Taubman S, Doyle J. Health care hotspotting - a randomized, controlled trial. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(2):152–162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gilbody S, Richards D, Brealey S, Hewitt C. Screening for depression in medical settings with the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ): a diagnostic meta-analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(11):1596–1602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Moreno G, Morales LS. Hablamos Juntos (together we speak): interpreters, provider communication, and satisfaction with care. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(12):1282–1288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hargraves JL, Hays RD, Cleary PD. Psychometric properties of the consumer assessment of health plans study (CAHPS) 2.0 adult core survey. Health Services Res. 2003;38(6 Pt 1):1509–1527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Morales LS, Weech-Maldonado R, Elliott M, Weidmer B, Hays RD. Psychometric properties of Spanish consumer assessments of health plans survey. Hispanic J Behav Sci. 2003; 25(3):386–409. [Google Scholar]

- 41.McDonald KM, Schultz E, Pineda N, Lonhart J, Chapman T, Davies S. Agency for Healthcare Research and QualityAgency for Healthcare Research and Quality. AHRQ Publication No. 12–0019-EF 2012; https://www.pcmh.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/attachments/care%20coord%20account%20measures%20for%20pc.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Clarke R, Bharmal N, Capua PD, et al. Innovative approach to patient-centered CareCoordination in primary care practices. Am J Managed Care. 2015;21(9):623–630. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Austin PC. An Introduction to propensity score methods for reducing the effects of confounding in observational studies. Multivar Behav Res. 2011;46(3):399–424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Daaleman TP, Ernecoff NC, Kistler CE, Reid A, Reed D, Hanson LC. The impact of a community-based serious illness care program on healthcare utilization and patient care experience. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67(4):825–830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Reckrey JM, Soriano TA, Hernandez CR, et al. The team approach to home-based primary care: restructuring care to meet individual, program, and system needs. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63(2):358–364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schubert CC, Myers LJ, Allen K, Counsell SR. Implementing geriatric resources for assessment and care of elders team care in a veterans affairs medical center: lessons learned and effects observed. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64(7):1503–1509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gawande A The hot spotters. The New Yorker. January 16, 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.