Summary

Although perovskite/two-dimensional (2D) materials heterojunctions have been employed to improve the optoelectronic performance of perovskite photodetectors and solar cells, effects of the intrinsic potential difference (ΔVin) of asymmetrical 2D materials, like Janus TMDs (J-TMDs), were not revealed yet. Herein, by investigating the optoelectronic properties of CsPbI3/J-TMDs heterojunctions, we find a reversible type-II band alignment related to the intensity and direction of ΔVin, suggesting that carrier transport paths can be reversed by modulating the contact configuration of J-TMDs in the heterojunctions. Meanwhile, the band offset, carrier transfer efficiency and optical properties of those heterojunctions are directly determined by the intensity and direction of ΔVin. Overall, CsPbI3/MoSSe heterojunction is suggested in this work with a tunneling probability of 79.65%. Our work unveils the role of ΔVin in asymmetrical 2D materials on the optoelectronic performances of lead halide perovskite devices, and provides a guideline to design high performance perovskite optoelectronic devices.

Subject areas: Surface chemistry, Nanotechnology, Materials science

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

An intrinsic potential difference (ΔVin) exists in asymmetrical Janus TMD (J-TMD)

-

•

A reversible type-II band alignment realized by modulating the contact configuration

-

•

The transport performance of CsPbI3/J-TMD heterojunction directly determined by ΔVin

-

•

The optical absorption is enlarged by modulating the direction and intensity of ΔVin

Surface chemistry; Nanotechnology; Materials science

Introduction

In recent years, lead halide perovskites have attracted great attention in the application of high-performance photovoltaic and optoelectronic because of their large optical absorption coefficient, low cost, simple preparation, etc. (Gu et al., 2020; Guzelturk et al., 2021; Tao et al., 2021, 2020; Wang et al., 2021a; Wang et al., 2020) Photodetectors based on lead halide perovskites have been widely applied in diverse fields including optical communication, remote sensing, military surveillance, imaging technology, and industry automation control. However, it should be noted that the organic-inorganic lead halide perovskite possesses the poor stability which hinders the development of perovskite devices (Li et al., 2019; Zhou and Zhao, 2019). Alternatively, all-inorganic cesium lead halide perovskite (CsPbX3) not only shows a more effective stability (Jiang et al., 2018; Seth et al., 2019), but also demonstrates excellent optoelectronic properties, such as direct optical band gaps, large optical absorption, and high luminescence efficiency (Nedelcu et al., 2015; Protesescu et al., 2015). These optoelectronic properties make CsPbX3, especially CsPbI3, promising for solar cells, light-emitting diodes, lasers, and photodetectors (Liu et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2015).

To further improve the optoelectronic performance of perovskite devices, heterojunction engineering, especially perovskite/2D material heterojunction has been becoming an effective approach (Zhang et al., 2021). For instance, CH3NH3PbI3/graphene heterojunction not only broadened the spectral photoresponsivity of perovskite photodetector, but also increased the effective quantum efficiency to 5 × 104% under an illumination power of 1 μW (Lee et al., 2015). Moreover, CsPbBr3/MoS2 heterojunction could increase the photoresponsivity and photodetectivity to 4.4 A/W and 2.5×1010 Jones, respectively, because of the high efficient photoexcited carrier separation at the interface between MoS2 and CsPbBr3 (Song et al., 2018). CsPbI3/phosphorus heterojunctions enhanced the light absorptions especially in the infrared region (Liu et al., 2018).

Compared to the symmetrical 2D materials, 2D asymmetrical polar materials Janus TMDs (J-TMDs, namely, MXY, M = Mo, W; X = S; Y=S, SE, Te in this work), which can be prepared by selenization or tellurization of symmetrical MoS2 in experiment (Lu et al., 2017; Yun et al., 2017), not only possess excellent optical absorption, tunable band gap, high carrier mobility, but also have the intrinsic potential difference (ΔVin) of J-TMDs by destroying the out-of-plane mirror symmetry which can be regarded as another degree of freedom for modulating their properties (Yin et al., 2021). Moreover, such intrinsic ΔVin has been found to promote the electron-hole separation, band levels variation, and mobility modulation, resulting in effective inhibition of carrier recombination and enhancement of responsivity (Dong et al., 2017; Er et al., 2018; Li et al., 2018; Lian et al., 2019; Thanh et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2020; Zhou et al., 2019). Inspired by these, it is thought that the optoelectronic performances of perovskite devices based on perovskite/TMDs heterojunctions may be further improved by the intrinsic ΔVin when the TMDs are replaced by the J-TMDs.

Herein, CsPbI3/J-TMDs (MXY, M = Mo, W; X = S; Y=S, SE, Te) heterojunctions are studied to unveil the roles of ΔVin in J-TMDs on the optoelectronic properties of CsPbI3 based device. The results demonstrate that all CsPbI3/J-TMDs heterojunctions in this work have a type-II band alignment, indicating that charge transfer rather than energy transfer dominates in CsPbI3/J-TMDs heterojunctions. Moreover, a reversed type-II band alignment happened when ΔVin deviates from the interface and increases further, suggesting that carrier transport paths can be reversed by modulating the contact configuration of J-TMDs in the heterojunctions. A better optoelectronic performance was found in the heterojunction based on PbI configuration rather than CsI configuration, resulting from the former higher work function and more complete structural framework. Meanwhile, the band offset, carrier transfer efficiency, and optical properties are directly dependent on both the intensity and direction of ΔVin. In addition, the heterojunction with a larger ΔVin pointing away from the interface possesses a smaller band offset with higher carrier transfer efficiency and optical absorption. CsPbI3/MoSSe heterojunction is recommended with a tunneling probability (PTB) of 79.65%. Our work unveils the role of intrinsic ΔVin in asymmetrical polar 2D materials on the optoelectronic performances of perovskite devices, and provides a guideline to design high performance perovskite optoelectronic devices.

Results and discussion

Isolated CsPbI3 surfaces and monolayer J-TMDs

Before investigating the electronic structures of CsPbI3/J-TMDs heterojunctions, the electronic structures of their isolated surfaces are calculated by PBE and HSE06 functionals. In addition, the calculated lattice parameters are listed in Table S1 and consistent with previous experimental and theoretical results. The calculated projected band structures and corresponding parameters of those isolated surfaces are illustrated in Figure S1 (PBE), Figure 1 (HSE06), and Table 1. It can be found that electronic structures of those isolated surfaces calculated by PBE and HSE06 functionals are similar except for bandgaps, where the bandgaps calculated by HSE06 functional are consistent with experimental values. Therefore, HSE06 functional is mainly applied to investigate the electronic structure of CsPbI3/J-TMDs heterojunctions in this work.

Figure 1.

The structure models and electronic structures od isolated CsPbI3 and J-TMDs

(A) The structure models for CsPbI3 surfaces and J-TMDs monolayers.

(B) Electronic band structures of CsI surface.

(C) Electronic band structures of PbI surface.

(D) Electronic band structures of MoS2 monolayer.

(E) Electronic band structures of MoSSe monolayer.

(F) Electronic band structures of MoSTe monolayer.

(G) Electronic band structures of WSTe monolayer.

(H) Planar-averaged electrostatics potentials of Janus TMDs along the direction normal to the interface region.

(I) Exciton binding energies and effective masses of Janus TMDs as functions of the ΔVin

Table 1.

Bandgaps, effective masses and exciton energies of isolated surface of CsPbI3 and J-TMDs monolayers

| Isolated surface | CsPbI3 |

MoS2 | MoSSe | MoSTe | WSTe | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CsI | PbI | ||||||

| Band gap/eV | HSE06 | 1.75 | 1.83 | 2.01 | 1.97 | 1.62 | 1.75 |

| PBE | 1.34 | 1.43 | 1.53 | 1.32 | 1.04 | 1.21 | |

| Experimental | 1.73 | 1.98 | – | – | – | ||

| me∗/m0 | 0.19 | 0.18 | 0.41 | 0.49 | 0.51 | 0.57 | |

| mh∗/m0 | 0.29 | 0.26 | 0.48 | 0.58 | 1.21 | 1.32 | |

| Ex/meV | 106.21 | 77.98 | 262.21 | 247.69 | 238.61 | 222.92 | |

Here, two types of CsPbI3 surface namely CsI and PbI surface are considered, as shown in Figure 1A. The CsI and PbI surfaces have a direct bandgap with 1.75 and 1.83 eV, respectively, which are consistent with the previous studies ( Liu et al., 2018). The conduction band minimum (CBM) and valence band maximum (VBM) of both the CsI and PbI surfaces are dominated by Pb p-orbitals and I p-orbitals, respectively, as is illustrated in Figures S2A and S2B. As for the effective masses me∗ and mh∗, they are 0.19 and 0.29 m0 for CsI surface, whereas 0.18 and 0.26 m0 for PbI surface, respectively; such effective masses are consistent with previous research (He et al., 2019). Correspondingly, the exciton binding energy Ex calculated is 106.21 meV for CsI surface which is larger than that of 77.98 meV for PbI surface, indicating a poor carries recombination for CsI surface compared with the PbI surface. In addition, as listed in Table S2, the energies of ECsI and EPbI surfaces are −57.17 and −58.96 eV, respectively, suggesting that the PbI surface is much more stable than the CsI surface.

For J-TMDs monolayer, their electronic structures are displayed in Figures 1D–1G and S2C–S2F. MoS2 monolayer has a direct bandgap with 2.01 eV, and its CBM and VBM are mainly consisted of Mo-d orbitals and a little contribution of S-p orbitals, which are consistent with previous reports (Kadantsev and Hawrylak, 2012; Santos and Kaxiras, 2013). It is thought that both the electron and hole are transported at the Mo-S bonds. The calculated effective masses me∗ and mh∗ of MoS2 are 0.41 and 0.48 m0, leading to the exciton binding energy of 262.21 meV, which are consistent with previous studies (Park et al., 2018; Pedersen et al., 2016). For J-TMDs, evident intrinsic potential difference (ΔVin) points from the heavy atoms Y side to light atoms X side are observed, as marked in Figures 1H and S3. The ΔVins are 0.61, 1.34, and 1.38 eV for Janus MoSSe, MoSTe, and WSTe, respectively, indicating that ΔVin can be enhanced significantly by altering the chalcogens (X) or enhanced slightly by altering the metals (M) of J-TMDs. As a result, the CBMs of J-TMDs are dominated by the hybrid orbitals between M d-orbitals and p-orbitals of heavy Y, whereas the VBMs are dominated by the hybrid orbitals between M d-orbitals and p-orbitals of light X, as demonstrated in Figures 1D–1G and S2C–S2F. It is thought that electrons and holes of J-TMDs are transported at the M−Y and M-X bonds, respectively, indicating an excellent ability of electron-hole separation for J-TMDs (Tao et al., 2019; Thanh et al., 2020). It is noted that MoSSe has a direct bandgap with 1.97 eV, whereas MoSTe and WSTe have an indirect bandgap with 1.62 and 1.75 eV, respectively. The bandgap of J-TMD reduces with the enlarging ΔVin by altering the X of J-TMDs, whereas an opposite character occurs while altering the M of J-TMDs. On the contrary, the effective masses significantly increase with the enhancing ΔVin by altering the X of J-TMDs, whereas they are slightly enlarged as the variation of ΔVin induced by altering X, as listed in Table 1 and Figure 1I. It is noted that variation of me∗ and mh∗ of J-TMDs are strongly and slightly tuned by the ΔVin of J-TMDs. As a result, the exciton binding energies of J-TMDs are lower than that of MoS2 monolayer, indicating the weaker carrier recombination for J-TMDs. Moreover, the exciton binding energies of J-TMDs decrease monotonously with the increasing ΔVin of J-TMDs. Moreover, Table S2 lists out the energies of those EJ-TMDs; the stability of J-TMDs changes to worse as the intrinsic ΔVin increases while being altered by chalcogens, and changes to better when ΔVin is being altered by metals. Hence, J-MoSSe seems to be a better choice because of its perfect properties and easy selenization of MoS2 in experiment. Such dependence of electronic and transport properties of J-TMDs on the strength of intrinsic ΔVin expands the tunability of optoelectronic properties and application of 2D material in CsPbI3/2D heterojunctions.

Binding energies

Figure S4 shows the structure models of CsPbI3/J-TMDs heterojunctions, and Figure S5 illustrates the binding energies (Eb) as functions of the interlayer separation. For CsPbI3/MoS2 heterojunction, when the interlayer separations of with CsI/MoS2 and PbI/MoS2 heterojunctions are 3.2 and 3.4 Å, respectively, binding energies of corresponding CsI/MoS2 and PbI/MoS2 heterojunctions reach to the lowest negative values of about −0.039 and −0.109 eV/atom, as listed in Table S3. It indicates that the CsPbI3/MoS2 heterojunctions, in particular the PbI/MoS2 heterojunction, with such interlayer separations are stable and possible to be fabricated in experiment, which is consistent with previous reports (He et al., 2019).Similar to the CsPbI3/MoS2 heterojunction, the larger interlayer distances and lower binding energies are observed for PbI/MoS2 heterojunctions than CsI/MoS2 heterojunctions, suggesting the more stable for PbI/MoS2 heterojunctions than CsI/MoS2 heterojunctions. Moreover, it is interesting that the interlayer separations of CsPbI3/J-TMDs heterojunctions are dependent on the interfacial contact character, where the interlayer separation of interface contacted by light atoms X is shorter than that contacted by heavy atoms Y. Such opposite phenomenon is suitable to the binding energies for CsPbI3/J-TMDs heterojunctions. For examples, the equilibrium interlayer separations and binding energies of CsI/S-MoSSe and CsI/Se-MoSSe heterojunctions are 3.2 Å and 0.060 eV/atom, and 3.4 Å and 0.038 eV/atom, respectively. Moreover, all the interlayer separations are higher than the sum of radii of Pb (or Cs) and X (or Y) atoms, suggesting the van der Waals heterojunction for CsPbI3/J-TMDs heterojunctions. Except for the interfacial contact character, the intrinsic potential differences of J-TMDs also affect the binding energies of CsPbI3/J-TMDs heterojunctions, where the Eb increases with the increment of ΔVin, as listed in Table S3. It suggests the poor stability for the CsPbI3/J-TMDs heterojunctions with large intrinsic potential difference.

Electronic structures

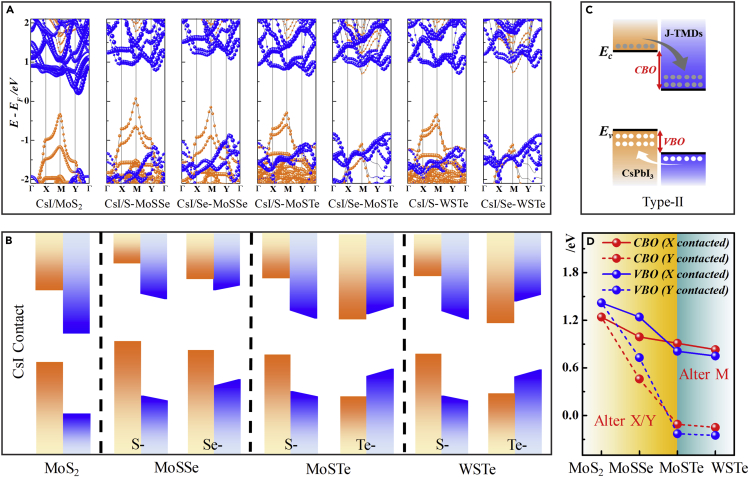

Figures 2A and S6A illustrate the projected band structures of CsI/J-TMDs and CsI/J-TMDs heterojunctions, respectively. It can be found that the electronic band structures of CsI/J-TMDs heterojunctions seem to be a simple sum of electronic band structures isolated CsI surface and J-TMDs monolayer, irrespective of heterojunction configurations. For example, the bandgaps of CsPbI3 and MoS2 parts for CsI/MoS2 heterojunctions are 1.79 and 1.97 eV (see Table 2), respectively, which are close to those of the isolated CsI surface (1.75 eV) and MoS2 monolayer (2.01 eV). Moreover, as shown in Figures 3 and S7, the CBM and VBM of isolated CsI part of CsI/MoS2 heterojunctions are dominated by Pb p-orbitals and I p-orbitals, respectively; the CBM and VBM of isolated MoS2 part of CsI/MoS2 heterojunctions both are dominated by Mo d-orbitals and S p-orbitals. The effective masses and exciton binding energy of CsI part and MoS2 part of CsI/MoS2 heterojunctions are 0.26 m0 of mh∗ and 101.61 meV, and 0.43 m0 of me∗ and 270.12 meV, respectively. These are close to those of isolated CsI surface and MoS2 monolayer, as listed in Tables 1 and 2. These phenomena are the typical characters for vdW heterojunction, suggesting the CsI/MoS2 vdW heterojunction. Similar characters are also observed for other CsI/J-TMDs vdW heterojunctions, no matter how the intrinsic ΔVins and contact characters of J-TMDs change, as demonstrated in Figure 2 and Table 2.

Figure 2.

The electronic structures of CsI/J-TMDs heterojunctions

(A) Projected band structures of CsI/J-TMDs heterojunctions.

(B) Schematic diagram of band alignment for CsI/J-TMDs heterojunctions.

(C) Schematic diagram of type-II heterojunctions.

(D) The band offsets of CsI/J-TMDs heterojunctions as a function of intrinsic ΔVin

Table 2.

The detailed bandgaps, CBM, VBM and effective masses (m0) of CsPbI3/J-TMDs heterojunctions

| Contacted surface | MoS2 | MoSSe |

MoSTe |

WSTe |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S- | Se- | S- | Te- | S- | Te- | |||

| CsI- | Eg (CsI) | 1.79 | 1.72 | 1.69 | 1.90 | 1.80 | 1.89 | 1.85 |

| Eg (MXY) | 1.97 | 1.96 | 1.96 | 1.73 | 1.64 | 1.92 | 1.75 | |

| CBM | Mo-d | Mo-d | Mo-d | Mo-d | Cs-p | Mo-d | Cs-p | |

| VBM | I-p | I-p | I-p | I-p | Mo-d | I-p | Mo-d | |

| me∗ | 0.43 | 0.59 | 0.61 | 0.55 | 0.20 | 0.55 | 0.15 | |

| mh∗ | 0.26 | 0.23 | 0.22 | 0.23 | 1.28 | 0.34 | 1.23 | |

| PbI- | Eg (CsI) | 1.76 | 1.80 | 1.88 | 1.96 | 1.94 | 2.04 | 2.02 |

| Eg (MXY) | 2.05 | 1.96 | 1.85 | 1.49 | 1.52 | 1.57 | 1.58 | |

| CBM | Mo-d | Mo-d | Mo-d | Mo-d | Cs-p | Mo-d | Cs-p | |

| VBM | I-p | I-p | I-p | I-p | Mo-d | I-p | Mo-d | |

| me∗ | 0.41 | 0.66 | 0.61 | 0.54 | 0.21 | 0.50 | 0.18 | |

| mh∗ | 0.29 | 0.24 | 0.19 | 0.20 | 1.36 | 0.25 | 1.47 | |

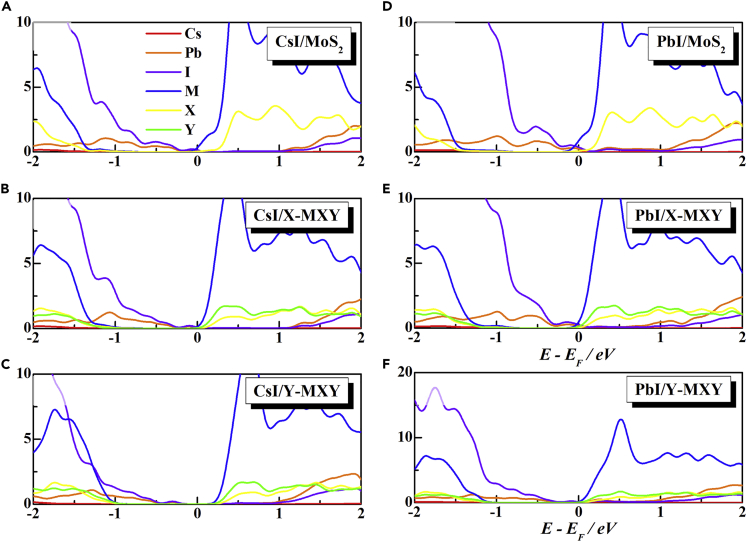

Figure 3.

Projected density of states for CsPbI3/J-TMDs heterojunctions

(A–C) Projected density of states for the heterojunctions based on CsI configuration.

(D–F) Projected density of states for the heterojunctions based on PbI configuration.

In addition, the VBM and CBM of CsI/J-TMDs heterojunctions are located at the perovskite (or J-TMD) parts and J-TMD (or perovskite) parts of heterojunctions, indicating the type-II band characters for all CsI/J-TMDs heterojunctions, as shown in Figures 2C and S6C. For example, the VBM and CBM of CsI/MoS2 heterojunctions are located at the CsI surface and MoS2 part, respectively, which are in good agreement with previous reports (He et al., 2019). It is thought that a strong ability of this heterojunction to move free electrons from perovskite to MoS2 part, and promote hole extraction from MoS2 part to perovskite surface. The conduction band offset (CBO) and valence band offset (VBO) of CsI/MoS2 heterojunctions are 1.24 and 1.42 eV, respectively. When the MoS2 layer with symmetrical structure is replaced by the J-TMD with asymmetrical structure, both the CBO and VBO of CsI/J-TMDs heterojunctions are reduced. Moreover, the band offsets, in particular the VBO, continue to decrease as the intrinsic potential difference (ΔVin) of J-TMD enlarges, as illustrated in Figure 2D. It is interesting that the decrement of CsI/J-TMDs heterojunction with heavy atom contact is stronger than that of CsI/J-TMDs heterojunction with light atom contact. As a result, the band offsets of type-II CsI/J-TMDs heterojunction with heavy atom contact are easy to turn into negative values, but the band offsets of type-II CsI/J-TMDs heterojunction with light atom contact keep positive values. It means that carrier transport paths of CsI/J-TMDs heterojunctions can be reversed by modulating the contact configuration of J-TMDs in the heterojunctions, although the CsI/J-TMDs heterojunctions remain the type-II band characters, as demonstrated in Figure S6C. Taking the CsI/MoSTe heterojunction as an example, the CBO (VBO) of CsI/Te-MoSTe heterojunction of about −0.11 eV (−0.23 eV) is smaller than that of CsI/S-MoSTe heterojunction of about 0.91 eV (0.81 eV), which are lower than that of CsI/MoS2 heterojunction of about 1.24 eV (1.42 eV). Moreover, photo-generated electron and hole of CsI/Te-MoSTe heterojunction are transport at CsPbI3 surface and MoSTe parts of heterojunctions, which are inverse to the CsI/S-MoSTe heterojunction whose photo-generated electron and hole are transport at the MoSTe and CsPbI3 parts, respectively. It is noted that the band offset of type-II heterojunction indicates the driving force and efficiency of carrier transfer at the type-II heterojunction. It suggests that the lower driving force and efficiency of electron (or hole) transfer from CsI surface (or J-TMDs layer) to J-TMDs layer (or CsI surface) for CsI/J-TMDs heterojunctions, in particular the heterojunctions with heavy atom contact, compared to those of CsI/MoS2 heterojunctions. Note that the direction of intrinsic ΔVins of J-TMD points from the heavy atomic layer to the light atomic layer of J-TMD. Thus, it is thought that the decrements of band offsets for CsI/J-TMDs heterojunctions are dependent of the direction and amount of intrinsic ΔVins of J-TMDs layers in the heterojunctions, where the CsI/J-TMDs heterojunctions show smaller band offsets when the directions of intrinsic ΔVins of J-TMDs layers point away from the contact region than those point to the contact region. In addition, because the intrinsic ΔVins of J-TMDs are significantly and gradually tuned by altering the chalcogens and metals of J-TMDs, respectively (see Figure 1), the band offsets of CsI/J-TMDs heterojunctions can be severely reduced by altering the chalcogens of J-TMDs, whereas they are slightly reduced by altering the metals of J-TMDs.

Compared to the CsI/J-TMDs heterojunctions, similar characters are observed for the PbI/J-TMDs vdW heterojunctions. However, the band offsets of PbI/J-TMDs vdW heterojunctions are larger than those of CsI/J-TMDs heterojunctions. Moreover, the variations of band offsets for PbI/J-TMDs vdW heterojunctions are more significantly tuned by the direction and strength of intrinsic potential difference than those of CsI/J-TMDs heterojunctions, as comparatively illustrated in Figures 2 and S6. In addition, it is noted that the intrinsic ΔVins of J-TMDs can result in the photo-generated electron and hole separation at the J-TMDs layer according to previous studies (Li et al., 2018; Lian et al., 2019; Thanh et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2020). Thus, the band structures of J-TMDs can be simplified as the oblique band levels. As a consequent, the photo-generated carrier can be transferred at the CsPbI3/J-TMDs contact region induced by the band offsets and J-TMDs layer induced by the intrinsic ΔVins of J-TMDs. Thus, in order to understand the band offsets and charge transfer at the CsPbI3J-TMDs heterojunctions, the band alignment diagrams of CsI/J-TMDs and PbI/J-TMDs heterojunctions are summarized in Figures 2B and S6B.

Transport properties

To further understand the carrier transfer at the CsPbI3/J-TMDs heterojunctions, energy band diagrams of CsPbI3/J-TMDs heterojunctions are illustrated in Figure 4. The energy levels of isolated CsPbI3 surface and J-TMDs layer are referenced to the vacuum level. The calculated work function (WF) of isolated CsI surface, PbI surface, and monolayer MoS2 are 4.65, 5.23, and 5.22 eV, respectively, which are consistent with previous studies (Cao et al., 2020; Matter, 2020). The carriers will flow until Fermi levels are lined up when perovskite surface and MoS2 contact. It is thought that there is a negative vacuum barrier (ΔV) between CsI surface and MoS2 layer upon forming CsI/MoS2 heterojunction with equilibrium Fermi level. As a result, CsI surface and MoS2 layer in CsI/MoS2 heterojunction demonstrate the upward and downward bending band levels, respectively (see Figure 4A), which will induce a positive energy barrier (ΔT) at when carrier transfers from CsI surface to MoS2 layer. Such vacuum barrier ΔV can be regarded as the driving force for carrier transfer at the heterojunction; such energy barrier ΔT hampers the carrier transfer efficiency at the heterojunctions. Compared to the CsI/MoS2 heterojunction, similar ΔV and ΔT are observed for the CsI/MoSSe heterojunction, except for the lower absolute values, because the MoSSe monolayer possesses the lower WF than the MoS2 monolayer. Moreover, the CsI/Se-MoSSe heterojunction shows the lower ΔV and ΔT than the CsI/S-MoSSe heterojunction, because the WF of MoSSe monolayer at the SE atomic layer is lower than that at the S atomic layer. This inconsistent WF induces the intrinsic potential difference ΔVin for MoSSe monolayer whose direction points from SE atomic layer to S atomic layer, which promotes electron transfer from the SE atomic layer to the S atomic layer of MoSSe monolayer. It means that CsI/MoSSe heterojunction, especially the CsI/Se-MoSSe heterojunction whose ΔVin direction points from SE atomic layer to S atomic layer, shows the weaker carrier transfer drive force and higher carrier transfer efficiency compared to the CsI/MoS2 heterojunction. According to the above analysis, increasing the intrinsic ΔVin by altering the X/Y and M atoms of MXY can further decrease the WF of J-TMD monolayer, as listed in Table S4. As a result, the WF of J-TMD, especially at the Y atomic layer, is lower than that of CsI surface. Consequently, the negative ΔV can turn into positive ΔV, and ΔT continues to decrease for CsI/J-TMD heterojunction with large ΔVin, as the ΔV and ΔT for CsI/Te-SMoTe and CsI/Te-SWTe heterojunctions displayed in Figure S8A. That is why the CsI/Te-SMoTe and CsI/Te-SWTe heterojunctions show the inversely type-II band alignments. It also indicates that the carrier transfer efficiency for CsI/J-TMD heterojunction can be improved by increasing the ΔVin of J-TMD.

Figure 4.

Schematic energy band diagrams for CsPbI3/J-TMDs heterojunctions

(A–C) Schematic energy band diagrams for the heterojunctions based on CsI configuration.

(D–F) Schematic energy band diagrams for the heterojunctions based on PbI configuration.

Different from the CsI/MoS2 heterojunctions, PbI/MoS2 heterojunctions demonstrate a positive ΔV because the WF of PbI surface is larger than that of MoS2 monolayer (see Figure 4D and Table S4). This positive ΔV hampers the electron transfers from the perovskite surface to MoS2 layer. Meanwhile, PbI surface and MoS2 layer in PbI/MoS2 heterojunction demonstrate the downward and upward bending band levels, respectively (see Figure 4D), which will induce a much lower energy barrier ΔT when the carrier transfers from PbI surface to the MoS2 layer. Different from the MoS2 monolayer, the MoSSe monolayer with an intrinsic ΔVin exhibits the lower WF than PbI surface, which resulting in the larger ΔV for PbI/MoSSe heterojunction than PbI/MoS2 heterojunction. It suggests the weaker drive force for charge transfer from perovskite to the MoSSe layer. Theoretically, the larger ΔV will induce the stronger band bending, which leads to the smaller ΔT for PbI/MoSSe heterojunction, in particular the PbI/Se-MoSSe heterojunction. As the intrinsic ΔVin increases, the WFs of J-TMDs will continue to decrease, which theoretically leads to the increasing ΔV and reducing ΔT for PbI/J-TMDs heterojunction, especially with the PbI/Y-MXY configuration, as displayed in Figures 4E and 4F. It is noted that PbI surface is p-type semiconductor, suggesting that hole transfers from PbI surface to J-TMDs layer. It will raise the band levels of J-TMDs layer. Meanwhile, the intrinsic ΔVin of J-TMD promotes hole transfers from the Y atomic layer to the X atomic layer of J-TMDs, which further increases the band levels of X atomic layer of J-TMDs. Consequently, the ΔT of PbI/J-TMD heterojunction with PbI/X-MXY configuration may be enlarged as the intrinsic ΔVin increases.

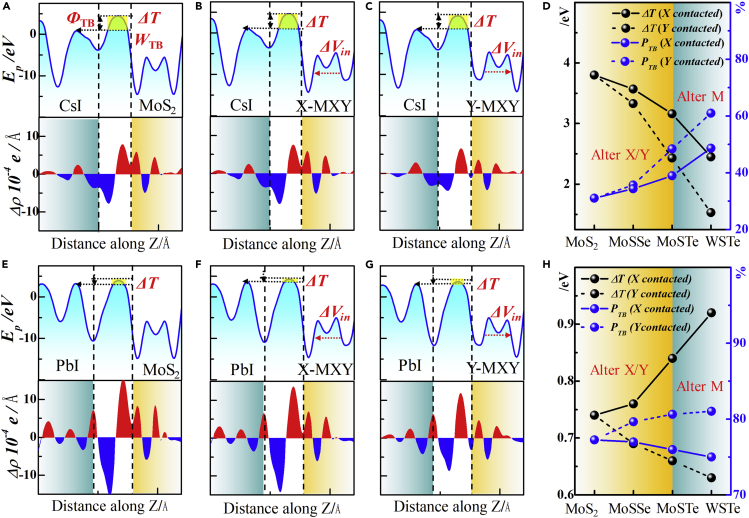

As an evidence of the analysis above, the planar-averaged electrostatics potentials (top) and planar-averaged charge density differences (bottom) of the CsPbI3/J-TMDs heterojunctions are demonstrated in Figure 5 and detailed in Figures S9–S11. It can be found that electrons and holes are mainly accumulated at the MoS2 and CsI layers of CsI/MoS2 heterojunction, respectively, suggesting that electrons transfer from the CsI surface to the MoS2 layer of heterojunction. Moreover, the charge transfer decreases when the MoS2 layer of heterojunction is replaced by J-TMDs layer with intrinsic ΔVin to form CsI/J-TMDs heterojunction, in particular the heterojunction with CsI/Y-MXY configurations, as displayed in Figures 5A–5C. The charge transfer of CsI/J-TMDs heterojunction further decreases with the enlarging intrinsic ΔVin (see Figure S12. These characters further confirm the above variation of ΔV for CsI/J-TMDs heterojunctions. Different from CsI/J-TMDs heterojunction, some electrons are accumulated at the PbI surface of PbI/J-TMDs heterojunctions, especially the heterojunction with PbI/X-MXY configuration, because holes are transferred from p-type PbI surface to J-TMDs. This is consistent with the above analysis of the band diagram. Moreover, the hole (electron) transfer are enhanced (reduced) for PbI/J-TMDs heterojunctions as the intrinsic ΔVin enlarges, which is in good agreement with the above ΔV for PbI/J-TMDs heterojunctions.

Figure 5.

Interfacial transportation properties for CsPbI3/J-TMDs heterojunctions

(A–C) Planar-averaged electrostatic potentials and charge density differences for the heterojunctions based on CsI configuration.

(D) The tunnel barriers and tunneling probabilities of CsI/J-TMDs as a function of intrinsic ΔVin.

(E–G) Planar-averaged electrostatic potentials and charge density differences for the heterojunctions based on PbI configuration.

(H) The tunnel barriers and tunneling probabilities of PbI/J-TMDs as a function of intrinsic ΔVin

It is noted that the above analyzed ΔT can be quantitatively marked in the electrostatics potentials of heterojunction, as seen in the yellow square in Figure 5. The detailed ΔTs of CsI/J-TMDs and PbI/J-TMDs heterojunctions are illustrated in Figures 5D and 5H. It can be found that the ΔTs of CsI/J-TMDs heterojunctions decline with the enlarging intrinsic ΔVin. Moreover, the ΔT reduction of CsI/J-TMDs heterojunctions with CsI/Y-MXY configuration is more significant than that with CsI/X-MXY configuration. It is thought that the carrier transfer efficiency at the CsI/J-TMDs heterojunctions, especially the heterojunction with CsI/Y-MXY configuration, increases with the enlarging intrinsic ΔVin. In contrast, the ΔTs of PbI/J-TMDs heterojunctions with PbI/X-MXY configuration enhance, whereas those of PbI/J-TMDs heterojunctions with PbI/Y-MXY configuration decline with the enlarging intrinsic ΔVin, which are consistent with the above analysis of ΔT for PbI/J-TMDs heterojunctions from band diagram.

To directly show the carrier transfer efficiency at the CsPbI3/J-TMDs heterojunctions, the tunneling probability (PTB) is calculated as follows (Yuan et al., 2020, 2021)

| (Equation 1) |

where me is the free electron mass of isolated CsPbI3 of about 0.18 m0, ħ is the reduced Plank's constant, and ΦTB and WTB are the height and full width at half maximum of the tunneling barrier, respectively. The tunneling probability PTB of CsPbI3/J-TMDs heterojunctions are detailed at Figures 5D and 5H. For the CsI/MoS2 heterojunction, the ΔT is about 3.8 eV with corresponding PTB of about 31.06%, which is consistent with previous studies, (He et al., 2019) indicating a poor carrier transfer efficiency at the CsI/MoS2 heterojunction. Moreover, as illustrated in Figure 5D, when intrinsic ΔVin is introduced into J-TMDs to form CsI/J-TMDs heterojunctions, the ΔT decreases and PTB increases with the enlarging intrinsic ΔVin, irrespective of the ΔVin direction, indicating an improved carrier transfer efficiency. In addition, the ΔT reaches to the lowest 1.53 eV with a highest PTB of about 60.98% in CsI/Te-WSTe heterojunction. Better than CsI/MoS2 heterojunction, the ΔT reduces to 0.74 eV with PTB of about 77.26% in the PbI/MoS2 heterojunction which is about twice as much as CsI/MoS2 heterojunction. Consistent with above analysis of ΔT and ΔVin in Figure 4, the ΔT (PTB) of PbI/J-TMD heterojunction enlarges (reduces) in PbI/X-MXY configuration, while being reduced (enlarges) in PbI/Y-MXY configuration as the intrinsic ΔVin increases. In addition, the PTB of PbI/Te-WSTe heterojunction reaches a maximum of 81.02% and a minimum ΔT of 0.63 eV. Those dates with an enhanced PTB suggests an improved carrier transfer efficiency in CsPbI3/J-TMDs heterojunctions compared with CsPbI3/MoS2 heterojunctions, indicating an effectively way to improve the interfacial transportation by introduce ΔVin to construct CsPbI3/J-TMDs heterojunctions.

Optical properties

It is important to study the light absorption capacity of heterojunction for its application in optoelectronic devices. The absorption spectra is calculated by the following formula

| (Equation 2) |

where is the absorption coefficient, is optical frequency, and and are the real and imaginary parts of the dielectric function, respectively. Figure 6 demonstrated the calculated absorption coefficients of the CsPbI3/J-TMDs heterojunctions, and it seems a higher optical absorption of those heterojunctions with PbI configuration rather than CsI configuration at infrared-visible range, but a lower absorption in UV region, result from the former stronger carrier transfer efficiency analyzed above. Moreover, the optical absorption of those CsI/J-TMDs heterojunctions drops in infrared region with increase in visible-ultraviolet range, and that trend enlarges further as the intrinsic ΔVin increases, irrespective of the configuration and the direction of ΔVin, as detailed in Figure S13. In UV region, those CsI/J-TMDs heterojunctions with CsI/Y-MXY configuration have higher absorption than those CsI/J-TMDs heterojunctions with CsI/X-MXY configuration, which is in good agreement with the above carrier transfer efficiency analyses. Same characteristics are observed in PbI/J-TMDs heterojunctions. These results suggest that forming CsPbI3/J-TMDs heterojunction with ΔVin has a significant enhancement for its application in photoelectric devices.

Figure 6.

Calculated absorption coefficients for CsPbI3/J-TMDs heterojunctions

In summary, the optoelectronic properties of CsPbI3/J-TMDs heterojunctions have been modulated by the intrinsic ΔVin here. It is found the heterojunction with a larger ΔVin pointing away from the interface possesses a smaller band offset with higher carrier transfer efficiency and optical absorption, but a reversed type-II band alignment occurs when ΔVin increases further, suggesting that carrier transport paths can be reversed by modulating the contact configuration of the J-TMDs in the heterojunctions. As a result, the CsPbI3/MoSSe heterojunction is suggested in this work with PTB of about 79.65%.

Conclusions

Here, the optoelectronic properties of CsPbI3/J-TMDs heterojunctions are studied by using the first-principle calculation to reveal the influence of intrinsic ΔVin on the interfacial transport properties of optoelectronic devices. Remarkably, we found that a modulable ΔVin exists in J-TMDs, which could be modulated significantly by altering chalcogens or modulated slightly by altering metals of J-TMDs. Moreover, the CsPbI3/J-TMDs heterojunctions have a type-II band alignment with the VBM and CBM located at the perovskite and J-TMDs parts, respectively, indicating an ability for separating electrons and holes continuously and effectively, similar to CsPbI3/MoS2 heterojunctions. In addition, the type-II band alignment is reversed when ΔVin deviates from the interface and increases further, suggesting that carrier transport paths can be reversed by modulating the contact configuration of J-TMDs in the heterojunctions. Meanwhile, a better optoelectronic performance is found in the heterojunction based on PbI configuration rather than CsI configuration, resulting from the former higher work function and more complete structural framework. The band offset, carrier transfer efficiency and optical absorption are directly determined by the intensity and direction of ΔVin. In addition, the heterojunction with a larger ΔVin pointing away from the interface possess a smaller band offset with higher carrier transfer efficiency and optical absorption, and CsPbI3/MoSSe heterojunction with PTB of about 79.65% is suggested in this work. Overall, modulating the intensity and direction of ΔVin can facilitate to formation type-II CsPbI3/J-TMDs heterojunctions with excellent interfacial carrier transfer efficiency, our findings are vital to design and realize novel high-performance lead halide perovskite-based optoelectronic device.

Limitations of the study

In this work, we introduced the interfacial transport modulation of lead halide perovskite by the intrinsic potential difference of asymmetrical 2D materials Janus TMDs based on CsPbI3/J-TMDs heterojunctions. The heterojunctions with ΔVin show excellent interfacial charge transport and absorption propriety. It would be more interesting to study the optoelectronic device based on CsPbI3/J-TMDs heterojunctions with ΔVin in experiment.

STAR★Methods

Key resources table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Software and algorithms | ||

| Vienna Ab-initio Simulation Package | Xidian University | VASP 5.4.1 |

Resource availability

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Jingjing Chang (jjingchang@xidian.edu.cn).

Materials availability

This study did not generate new unique reagents.

Experimental model and subject details

Our study does not use experimental models typical in the life sciences.

Method details

All calculations is performed using density functional theory (DFT), as implemented in the Vienna ab initio simulation package (VASP) code(Allouche, 2012). The projector-augmented wave (PAW) method is used to describe the interaction between ion cores and valence electrons(Bloechl, 1994). Perdew-Burk-Ernzerhof (PBE) exchange-correlation functional is employed. Van der Waals (vdW) interaction is applied total energies and forces by means of DFT-D2 method(Ilawe et al., 2015; Tran et al., 2007). The cutoff energy of plane-wave is set to be 400 eV. The convergence criterion is set to be 1 × 10−5 eV for the self-consistent process, and all atoms are allowed to be fully relaxed until the atomic Hellmann-Feynman forces are less than 0.01 eV/Å−1, respectively. A vacuum of 15 Å is considered along z direction to avoid artificial interlayer interactions. A 9 × 9×1 k-sampling generated by the Monkhorst-Pack scheme is used for the Brillouin zone integration. The hybrid functional of Heyd-Scuseria-Ernzerhof (HSE06) with the spin−orbital coupling (SOC), which adopts a mixing parameter of 0.25 and a screening parameter of 0.2 Å−1 for the Hartree-Fock exchange, is used to correct the electronic structures(Heyd et al., 2005; Heyd and Scuseria, 2004).

The CsPbI3/J-TMDs heterojunctions are composed of 1 × 1 supercell of CsPbI3 (001) surface and 2×√3 supercell of J-TMDs (001) surface. The average lattice mismatches of CsPbI3/J-TMDs heterojunctions are less than 2.39%.

To obtain the stable CsPbI3/J-TMDs heterojunctions, the binding energies (Eb) of CsPbI3/J-TMDs heterojunctions are calculated using the formula (He et al., 2019)

| (Equation 3) |

where , and respectively represent the energies of CsPbI3/J-TMDs heterojunctions, isolated CsPbI3 surface and monolayer J-TMDs. N represents the atoms number of the corresponding CsPbI3/J-TMDs heterojunctions.

The Wannier-Mott exciton binding energy (Ex) estimated based on the effective mass theory can be calculated as(Guo et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2021b)

| (Equation 4) |

where is the reduced mass given from the effective masses of electron and hole as follow

| (Equation 5) |

in which ε is the dielectric constant of surrounding material in the Coulomb interaction, me∗ and mh∗ are the effective masses of electron and hole, respectively.

The charge density difference along z direction Δρ(z) was characterized as(Zhang et al., 2019)

| (Equation 6) |

where , and are the charge densities of CsPbI3/J-TMDs heterojunctions, isolated CsPbI3 surface and monolayer J-TMDs, respectively.

Quantification and statistical analysis

Our study does not include statistical analysis or quantification.

Additional resources

Our study does not include any additional resources.

Acknowledgments

This work was financially supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2021YFA0715600, 2018YFB2202900), National Natural Science Foundation of China (52192610, 61804111), the 111 Project (B12026), Initiative Postdocs Supporting Program (BX20180234), China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2018M643578), Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities, and the Innovation Fund of Xidian University. The numerical calculations in this paper have been done on the HPC system of Xidian University.

Author contributions

H.D.Y. carried out DFT calculations, data analysis, and wrote the manuscript. J.J.C. and J. S. conceived the idea and revised the manuscript. S.Y.Z., J.Y.D., Z.H.L., J.C.Z., and J.Z. contributed to some analysis of the data. J.J.C., J.C.Z., and Y.H. supervised the project.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Published: March 18, 2022

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2022.103872.

Contributor Information

Jie Su, Email: sujie@xidian.edu.cn.

Jingjing Chang, Email: jjingchang@xidian.edu.cn.

Supplemental information

Data and code availability

Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this work paper is available from the Lead Contact upon request.

References

- Allouche A. Software news and updates gabedit — a graphical user interface for computational chemistry softwares. J. Comput. Chem. 2012;32:174–182. doi: 10.1002/jcc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloechl P.E. Projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B. 1994;50:17953. doi: 10.1103/physrevb.50.17953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao Y.H., Bai J.T., Feng H.J. Perovskite termination-dependent charge transport behaviors of the CsPbI3/black phosphorus van der Waals heterostructure. Chin. Phys. Lett. 2020;37:107301. doi: 10.1088/0256-307X/37/10/107301. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dong L., Lou J., Shenoy V.B. Large in-plane and vertical piezoelectricity in janus transition metal dichalchogenides. ACS Nano. 2017;11:8242–8248. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.7b03313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Er D., Ye H., Frey N.C., Kumar H., Lou J., Shenoy V.B. Prediction of enhanced catalytic activity for hydrogen evolution reaction in janus transition metal dichalcogenides. Nano Lett. 2018;18:3943–3949. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.8b01335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu E., Tang X., Langner S., Duchstein P., Zhao Y., Levchuk I., Kalancha V., Stubhan T., Hauch J., Egelhaaf H.J., et al. Robot-based high-throughput screening of antisolvents for lead halide perovskites. Joule. 2020;4:1806–1822. doi: 10.1016/j.joule.2020.06.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Y.J., Su J., Wang L., Lin Z., Hao Y., Chang J. Improved doping and optoelectronic properties of Zn-doped Cspbbr3 perovskite through Mn codoping approach. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2021;12:3393–3400. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpclett.1c00611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guzelturk B., Winkler T., Van de Goor T.W.J., Smith M.D., Bourelle S.A., Feldmann S., Trigo M., Teitelbaum S.W., Steinrück H.G., de la Pena G.A., et al. Visualization of dynamic polaronic strain fields in hybrid lead halide perovskites. Nat. Mater. 2021;20:618–623. doi: 10.1038/s41563-020-00865-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He J., Su J., Lin Z., Zhang S., Qin Y., Zhang J., Chang J., Hao Y. Theoretical studies of electronic and optical behaviors of all-inorganic CsPbI3 and two-dimensional MS2 (M = Mo, W) heterostructures. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2019;123:7158–7165. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcc.8b12350. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Heyd J., Peralta J.E., Scuseria G.E., Martin R.L. Energy band gaps and lattice parameters evaluated with the Heyd-Scuseria-Ernzerhof screened hybrid functional. J. Chem. Phys. 2005;123:174101. doi: 10.1063/1.2085170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heyd J., Scuseria G.E. Efficient hybrid density functional calculations in solids: assessment of the Heyd-Scuseria-Ernzerhof screened coulomb hybrid functional. J. Chem. Phys. 2004;121:1187–1192. doi: 10.1063/1.1760074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ilawe N.V., Zimmerman J.A., Wong B.M. Breaking badly: DFT-D2 gives sizeable errors for tensile strengths in palladium-hydride solids. J. Chem. Theor. Comput. 2015;11:5426–5435. doi: 10.1021/acs.jctc.5b00653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y., Yuan J., Ni Y., Yang J., Wang Y., Jiu T., Yuan M., Chen J. Reduced-dimensional α-CsPbX3 perovskites for efficient and stable photovoltaics. Joule. 2018;2:1356–1368. doi: 10.1016/j.joule.2018.05.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kadantsev E.S., Hawrylak P. Electronic structure of a single MoS2 monolayer. Solid State Commun. 2012;152:909–913. doi: 10.1016/j.ssc.2012.02.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y., Kwon J., Hwang E., Ra C.H., Yoo W.J., Ahn J.H., Park J.H., Cho J.H. High-performance perovskite-graphene hybrid photodetector. Adv. Mater. 2015;27:41–46. doi: 10.1002/adma.201402271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li R., Cheng Y., Huang W. Recent progress of janus 2D transition metal chalcogenides: from theory to experiments. Small. 2018;14:1–11. doi: 10.1002/smll.201802091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Zhou W., Li Y., Huang W., Zhang Z., Chen G., Wang H., Wu G.H., Rolston N., Vila R., et al. Unravelling degradation mechanisms and atomic structure of organic-inorganic halide perovskites by cryo-EM. Joule. 2019;3:2854–2866. doi: 10.1016/j.joule.2019.08.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lian J.C., Huang W.Q., Hu W., Huang G.F. Electrostatic potential anomaly in 2D Janus transition metal dichalcogenides. Ann. Phys. 2019;531:1–10. doi: 10.1002/andp.201900369. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu A., Almeida D.B., Bonato L.G., Nagamine G., Zagonel L.F., Nogueira A.F., Padilha L.A., Cundiff S.T. Multidimensional coherent spectroscopy reveals triplet state coherences in cesium lead-halide perovskite nanocrystals. Sci. Adv. 2021;7:1–7. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abb3594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu B., Long M., Cai M.Q., Yang J. Interface engineering of CsPbI3-black phosphorus van der Waals heterostructure. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2018;112:043901. doi: 10.1063/1.5016868. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lu A.Y., Zhu H., Xiao J., Chuu C.P., Han Y., Chiu M.H., Cheng C.C., Yang C.W., Wei K.H., Yang Y., et al. Janus monolayers of transition metal dichalcogenides. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2017;12:744–749. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2017.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matter C. Interfacial electronic properties of 2D/3D ( PtSe2/CsPbX3) perovskite heterostructure 2. J. Phys. Condens. Matter. 2020;32:445004. doi: 10.1088/1361-648X/aba775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nedelcu G., Protesescu L., Yakunin S., Bodnarchuk M.I., Grotevent M.J., Kovalenko M.V. Fast anion-exchange in highly luminescent nanocrystals of cesium lead halide perovskites (CsPbX3, X = Cl, Br, I) Nano Lett. 2015;15:5635–5640. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.5b02404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park S., Mutz N., Schultz T., Blumstengel S., Han A., Aljarb A., Li L.J., List-Kratochvil E.J.W., Amsalem P., Koch N. Direct determination of monolayer MoS2 and WSe2 exciton binding energies on insulating and metallic substrates. 2D Mater. 2018;5:025003. doi: 10.1088/2053-1583/aaa4ca. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen T.G., Latini S., Thygesen K.S., Mera H., Nikolić B.K. Exciton ionization in multilayer transition-metal dichalcogenides. New J. Phys. 2016;18:073043. doi: 10.1088/1367-2630/18/7/073043. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Protesescu L., Yakunin S., Bodnarchuk M.I., Krieg F., Caputo R., Hendon C.H., Yang R.X., Walsh A., Kovalenko M.V. Nanocrystals of cesium lead halide perovskites (CsPbX3, X = Cl, Br, and I): novel optoelectronic materials showing bright emission with wide color gamut. Nano Lett. 2015;15:3692–3696. doi: 10.1021/nl5048779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos E.J.G., Kaxiras E. Electrically driven tuning of the dielectric constant in MoS2 layers. ACS Nano. 2013;7:10741–10746. doi: 10.1021/nn403738b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seth S., Ahmed T., De A., Samanta A. Tackling the defects, stability, and photoluminescence of CsPbX3 perovskite nanocrystals. ACS Energy Lett. 2019;4:1610–1618. doi: 10.1021/acsenergylett.9b00849. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Song X., Liu X., Yu D., Huo C., Ji J., Li X., Zhang S., Zou Y., Zhu G., Wang Y., et al. Boosting two-dimensional MoS2/CsPbBr3 photodetectors via enhanced light absorbance and interfacial carrier separation. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2018;10:2801–2809. doi: 10.1021/acsami.7b14745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao W.-L., Mu Y., Hu C.-E., Cheng Y., Ji G.-F. Electronic structure, optical properties, and phonon transport in Janus monolayer PtSSe via first-principles study. Philos. Mag. 2019;99:1025–1040. doi: 10.1080/14786435.2019.1572927. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tao W., Zhang C., Zhou Q., Zhao Y., Zhu H. Momentarily trapped exciton polaron in two-dimensional lead halide perovskites. Nat. Commun. 2021;12:1–8. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-21721-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao W., Zhou Q., Zhu H. Dynamic polaronic screening for anomalous exciton spin relaxation in two-dimensional lead halide perovskites. Sci. Adv. 2020;6:2–10. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abb7132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thanh V. Van, Van N.D., Truong D. Van, Saito R., Hung N.T. First-principles study of mechanical, electronic and optical properties of Janus structure in transition metal dichalcogenides. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2020;526:146730. doi: 10.1016/j.apsusc.2020.146730. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tran F., Laskowski R., Blaha P., Schwarz K. Performance on molecules, surfaces, and solids of the Wu-Cohen GGA exchange-correlation energy functional. Phys. Rev. B Condens. Matter. 2007;75:1–14. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.75.115131. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang K., Xing G., Song Q., Xiao S. Micro- and nanostructured lead halide perovskites: from materials to integrations and devices. Adv. Mater. 2021;33:1–19. doi: 10.1002/adma.202000306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L., Su J., Guo Y., Lin Z., Hao Y., Chang J. 97.3% Pb-reduced CsPb1- xGexBr3 perovskite with enhanced phase stability and photovoltaic performance through surface Cu doping. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2021;12:1098–1103. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpclett.0c03580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Yiliu, Wan Z., Qian Q., Liu Y., Kang Z., Fan Z., Wang P., Wang Yekan, Li C., Jia C., et al. Probing photoelectrical transport in lead halide perovskites with van der Waals contacts. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2020;15:768–775. doi: 10.1038/s41565-020-0729-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin W.-J., Tan H.-J., Ding P.-J., Wen B., Li X.-B., Teobaldi G., Liu L.-M. Recent advances in low-dimensional Janus materials: theoretical and simulation perspectives. Mater. Adv. 2021;2:7543–7558. doi: 10.1039/d1ma00660f. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan H., Su J., Guo R., Tian K., Lin Z., Zhang J., Chang J., Hao Y. Contact barriers modulation of graphene/β-Ga2O3 interface for high-performance Ga2O3 devices. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2020;527:146740. doi: 10.1016/j.apsusc.2020.146740. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan H., Su J., Zhang P., Lin Z., Zhang Jincheng, Zhang Jie, Chang J., Hao Y. Tuning the intrinsic electric field of janus-TMDs to realize high-performance β-Ga2O3 device based on β-Ga2O3/janus-TMD heterostructures. Mater. Today Phys. 2021;21:100549. doi: 10.1016/j.mtphys.2021.100549. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yun S.J., Han G.H., Kim H., Duong D.L., Shin B.G., Zhao J., Vu Q.A., Lee J., Lee S.M., Lee Y.H. Telluriding monolayer MoS2 and WS2 via alkali metal scooter. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:1–10. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-02238-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang D., Eaton S.W., Yu Y., Dou L., Yang P. Solution-phase synthesis of cesium lead halide perovskite nanowires. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015;137:9230–9233. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b05404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L., Yang Z., Gong T., Pan R., Wang H., Guo Z., Zhang H., Fu X. Recent advances in emerging Janus two-dimensional materials: from fundamental physics to device applications. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2020;8:8813–8830. doi: 10.1039/d0ta01999b. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S., Su J., Lin Z., Tian K., Guo X., Zhang J., Chang J., Hao Y. Beneficial role of organolead halide perovskite CH3NH3PbI3/SnO2 interface: theoretical and experimental study. Adv. Mater. Inter. 2019;6:1–9. doi: 10.1002/admi.201900400. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z., Wang S., Liu X., Chen Y., Su C., Tang Z., Li Y., Xing G. Metal halide perovskite/2D material heterostructures: syntheses and applications. Small Methods. 2021;5:1–36. doi: 10.1002/smtd.202000937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou W., Chen J., Yang Z., Liu J., Ouyang F. Geometry and electronic structure of monolayer, bilayer, and multilayer janus WSSe. Phys. Rev. B. 2019;99:1–7. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.99.075160. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y., Zhao Y. Chemical stability and instability of inorganic halide perovskites. Energy Environ. Sci. 2019;12:1495–1511. doi: 10.1039/c8ee03559h. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this work paper is available from the Lead Contact upon request.