Abstract

Women at high risk for breast cancer may benefit from enhanced screening and risk-reduction strategies. However, limited time during clinical encounters is one barrier to routine breast cancer risk assessment. We evaluated if electronic health record (EHR) data downloaded using Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resources (FHIR) is sufficient for breast cancer risk calculation in our decision support tools, RealRisks and BNAV. We accessed EHR data using FHIR for six patient advocates, and downloaded and parsed XML documents. We searched for relevant clinical variables, and evaluated if data was sufficient to calculate risk using validated models (Gail, Breast Cancer Screening Consortium [BCSC], BRCAPRO). While only one advocate had sufficient EHR data to calculate risk using the BCSC model only, we identified variables including age, race/ethnicity, mammographic density, and prior breast biopsy in most advocates. EHR data from FHIR could be incorporated into automated breast cancer risk calculation in clinical decision support tools.

Introduction

Breast cancer is the most common cancer among women in the United States, with approximately 280,000 new cases and 40,000 deaths from breast cancer each year1. While breast cancer mortality has declined over the past three decades because of improved detection and therapeutic advances, this decline has begun to plateau, particularly among racial/ethnic minorities2. The identification of women who could benefit from enhanced breast cancer screening and preventive measures could further improve breast cancer mortality. Women at high risk for breast cancer, defined as an estimated 5-year risk of invasive breast cancer ≥ 1.67% and/or lifetime risk ≥ 20%, are eligible for chemoprevention with anti-estrogen agents, which reduce the risk of invasive breast cancer by approximately 50% to 65%3-8. In addition, multiple national medical organizations recommend more intensive screening with annual mammography and consideration of supplemental breast MRI or ultrasound among high-risk women9-11. However, rates of chemoprevention uptake remain low12, with barriers that include concerns about potential side effects of treatment, insufficient knowledge about breast cancer risk assessment and chemoprevention among patients and providers, and time constraints during clinical encounters13-16. There is therefore a clear unmet need for interventions to facilitate accurate breast cancer risk assessment and enhance shared decision-making about breast cancer screening and risk-reducing measures.

We have developed the web-based decision support tools RealRisks and Breast cancer risk NAVIgation (BNAV) for patients and primary care providers, respectively, that calculate an individual patient’s estimated breast cancer risk using validated models17-19 and include interactive educational modules on breast cancer risk assessment, genetic testing, screening, and chemoprevention20-22. RealRisks is patient-facing and available in English and Spanish, while BNAV is provider-facing. Through these interventions, we aim to improve accuracy of patients’ breast cancer risk perception, enhance breast cancer screening and chemoprevention knowledge, and inform decisions regarding genetic testing, screening and risk reduction. One barrier to seamless integration of RealRisks and BNAV into clinic workflow is the requirement for manual input of patients’ personal and family history for individualized breast cancer risk calculations. Current breast cancer risk models incorporate information including patient age, race/ethnicity, breast density (assessed during mammography), reproductive history, prior breast biopsy (and pathologic diagnoses), and family history. Automation of patients’ breast cancer risk calculations using data extracted from the electronic health record (EHR) could allow for more rapid, routine risk assessment. In addition, automated presentation of patients’ relevant medical histories to patients and providers could facilitate shared decision-making regarding therapeutic decisions such as recommendations regarding chemopreventive agents and lifestyle modification for risk reduction.

Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resources (FHIR) is a standard and application programming interface (API) created by the Health Level Seven International (HL7) health-care standards organization for the exchange of electronic healthcare information across platforms, particularly to support automated clinical decision support23. To facilitate faster, logical, and consistent data exchange among healthcare applications, FHIR defines and organizes data elements into “resources,” such as “Condition,” “Procedure,” and “FamilyMemberHistory,” that are easily identified and understood by recipient applications. Multiple widely-used EHR vendors, including Epic and Cerner, support FHIR in order to comply with national regulatory requirements for interoperability from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) and Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology (ONC)24,25. FHIR has previously been evaluated as a potential method of automatically populating documentation and registries in clinical trials26-28, which might allow for streamlined identification of potential candidates for enrollment and more seamless clinical trial data sharing. FHIR therefore might also facilitate automated breast cancer risk calculation.

Utilizing a unique multidisciplinary team composed of biomedical informaticists, software developers, and medical oncologists from Columbia University Irving Medical Center in New York, NY, we evaluated whether the FHIR standard could support automated breast cancer risk calculations in RealRisks and BNAV as well as presentation of relevant patient medical history to patients and providers to facilitate shared decision-making.

Methods

Clinical Variables of Interest for Risk Calculation

Our primary objective was to find clinical variables within patient data downloaded from the FHIR API to allow for future automation of breast cancer risk calculation in RealRisks and BNAV. RealRisks and BNAV use two validated risk models, the Gail17 and Breast Cancer Screening Consortium18 models, to estimate a patient’s breast cancer risk, and the BRCAPRO tool to estimate a patient’s risk of carrying a deleterious mutation in BRCA1 and/or BRCA219, which are associated with up to an 80% lifetime risk of developing breast cancer29. The clinical variables required for these models are summarized below (Table 1). While there are differences across models in the types of variables required, variables generally fall into one of five categories: 1) Demographics, 2) Reproductive factors, 3) Family history of breast cancer, 4) Breast pathology , and 5) Breast imaging.

Table 1.

Summary of variables required for breast cancer risk calculation according to the Gail, Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium (BCSC), and BRCAPRO models.

| Variable | Model | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Gail | BCSC | BRCAPRO | |

| Demographics | |||

| Age | X | X | X |

| Race/Ethnicity | X | X | X |

| Reproductive Factors | |||

| Age at first live birth | X | ||

| Age at first menstrual period | X | ||

| Family Cancer History | |||

| First-degree relative with breast cancer | X | X | |

| Second-degree relative with breast cancer | X | ||

| Relative with ovarian cancer | X | ||

| Relative with male breast cancer | X | ||

| Relative with bilateral breast cancer | X | ||

| Ashkenazi Jewish descent | X | ||

| Breast Pathology | |||

| History of benign breast biopsy | X | X | |

| # of breast biopsies | X | ||

| History of atypical hyperplasia | X | ||

| Detailed breast pathology results | X | ||

| Breast Imaging | |||

| Mammographic density (BI-RADS) | X | ||

Of note, the BCSC model requires classification of pathology results into: 1) Prior biopsy, unknown diagnosis; 2) Non-proliferative lesion; 3) Proliferative changes without atypia; 5) Proliferative changes with atypia; 6) Lobular carcinoma in situ, as well as classification of mammographic density into the four BI-RADS categories: 1) Almost entirely fatty; 2) Scattered fibroglandular densities; 3) Heterogeneously dense; 4) Extremely dense.

In addition, a secondary objective was to find additional relevant medical history within patient data downloaded from the FHIR API that could be presented within RealRisks and BNAV with the goal of facilitating shared decision-making about chemoprevention and other risk-aligned preventive options. The variables of interest are summarized below (Table 2). These variables were chosen for their potential to guide choice of chemoprevention (for example, menopausal status, history of thrombosis or endometrial cancer, osteoporosis), discussion of testing for hereditary cancer syndromes (family history of non-breast cancers including pancreatic and prostate), and recommendation for other non-chemoprevention risk-reducing measures (for example, alcohol use, body mass index [BMI]).

Table 2.

Summary of variables of interest to facilitate shared decision-making about breast cancer prevention.

| Variable |

|---|

| Personal Medical and Surgical History |

| History of venous or arterial thrombosis, pulmonary embolism |

| Cardiovascular risk factors: Hypertension, Hyperlipidemia, Diabetes mellitus, Coronary artery disease, Congestive heart failure |

| Osteoporosis or osteopenia |

| Endometrial cancer |

| Hysterectomy and/or oophorectomy |

| Bilateral mastectomy |

| Gynecologic History |

| Menopausal status (premenopausal, perimenopausal, postmenopausal) |

| Age at menopause |

| Number of live births |

| Use of oral contraceptives |

| Use of hormone replacement therapy |

| Social History |

| Alcohol use |

| Smoking history |

| Drug use |

| Vital Signs |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) |

| Systolic and diastolic blood pressure |

| Medications (Current or Previous) |

| Chemoprevention (tamoxifen, raloxifene, anastrozole, exemestane) |

| Oral contraceptive pills |

| Estrogen- and/or progesterone-containing medications |

| Family Cancer History |

| Relative with pancreatic cancer |

| Relative with prostate cancer |

| Relative with colorectal cancer |

| Relative with endometrial cancer |

| Imaging |

| Breast magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) |

| Breast ultrasound |

| Bone density scan (DEXA) |

| Genetic Testing/Counseling |

| Genetic counseling notes |

| Germline genetic testing results (BRCA1/2, multigene panel testing) |

| Lab Tests |

| FSH, LH, estradiol (to assess menopausal status) |

Download of Patient Data from FHIR API

We invited six patient advocates to access RealRisks and allow for their EHR data to be downloaded using our RealRisks SMART on FHIR add-on. We used FHIR versions Second Draft Standard for Trial Use (DSTU2), Release 3 Standard for Trial Use (STU3), and Release 4 (R4), and only accessed data from medical providers utilizing the Epic EHR. In order to locate clinical variables within FHIR, we downloaded data from the following FHIR resources: “Patient,” “CarePlan,” “DiagnosticReport,” “Condition,” “MedicationStatement,” “Procedure,” “Observation” (Smoking History, Vitals, Labs), “FamilyMemberHistory,” and “DocumentReference” (Consolidated-Clinical Document Architecture [CCDA] documents). These resources consisted of documents formatted via XML.

Data Parsing

We automatically parsed patient birthdate, race, and ethnicity from the FHIR “Patient” resource. The remainder of data from the FHIR API was downloaded the form of XML documents, which we parsed to have a tree structure using the lxml package (version 4.5.2) in Python (version 3.8.3). Two file types, “Patient Health Summary” and “Encounter Summary,” as well as many components contained in these files (such as patient allergies, medications, problems, test results, and coded diagnoses) were identified and separated for information extraction. Keywords related to the variables of interest were searched using regular expression and then exported.

Results

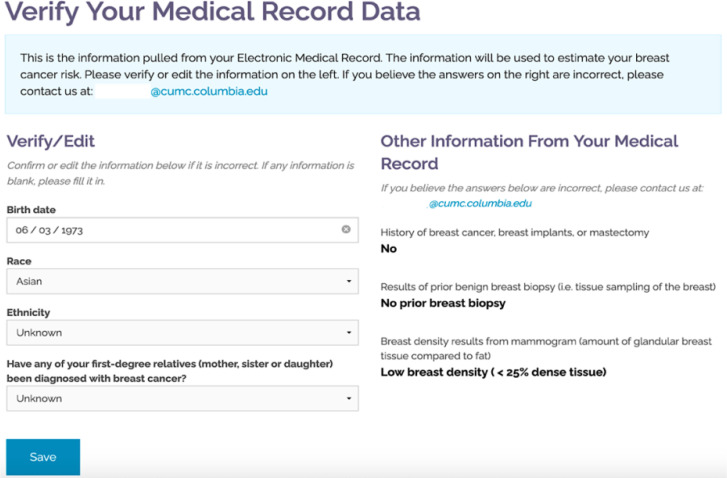

We successfully accessed EHR data for all six patient advocates. We automatically populated patient birthdate, race and ethnicity from the FHIR “Patient” resource into the RealRisks application. The RealRisks patient-facing window for risk calculation using the BCSC model (Figure 1) incorporates automatically populated variables alongside variables that were manually populated by the study team at time of patient RealRisks account creation.

Figure 1.

Example of a RealRisks patient-facing window for risk calculation using the BCSC model. Birthdate, race, and ethnicity (on the left) are automatically populated from the FHIR “Patient” resource. Family history of breast cancer in a first-degree relative was not auto-populated, and was documented as “unknown.” When family history is not available in the EHR, patients can enter this data by interacting with the pedigree generating function in RealRisks. On the right, variables including personal history of breast cancer or surgery, mammographic density, and prior breast biopsy were manually populated by the study team at the time of RealRisks account creation, and the patient is given the option to request changes in the current version.

We then parsed the “Patient Health Summary” and “Encounter Summary” XML files for each of the six advocates. While each patient had one “Patient Health Summary” file summarizing key clinical data, a single patient could have multiple “Encounter Summary” documents, with each file representing a single encounter (such as office visit, hospitalization, imaging study). For example, one patient advocate had 153 “Encounter Summary” files representing 153 separate encounters in Epic. The contents of these files are summarized below (Table 3).

Table 3.

Contents of “Patient Health Summary” and “Encounter Summary” XML files downloaded from FHIR. A component would be present in the document if the patient has relevant records.

| Component Name | LOINC Code | Description of Contents |

|---|---|---|

| Patient Health Summary | ||

| Patient information | Patient name, gender, birth date, marital status, religion, race, ethnicity, language. | |

| Allergies | 48765-2: Allergies and adverse reactions Document | Allergies, associated reactions, and severity. Substance codes in RxNorm and FDA Unique Ingredient Identifier (UNII). Reaction codes in SNOMED-CT. |

| Medications | 10160-0: History of Medication use Narrative | Active medications, medication start time, doses, administration time, and administration methods. Drug codes in but not limited to RxNorm. |

| Active Problems | 11450-4: Problem list - Reported | Active problems and time. Codes in SNOMED-CT, ICD9, ICD10, and Intelligent Medical Objects ProblemIT. |

| Resolved Problems | 11348-0: History of past illness | Resolved problems and time. Codes in SNOMED-CT, ICD9, ICD10, and Intelligent Medical Objects ProblemIT. |

| Immunizations | 11369-6: History of Immunization Narrative | Immunization names, time, manufacturers, and performers. Substance codes in CVX. |

| Procedures | 47519-4: History of Procedures Document | Procedure names, time, reasons of performing, and performer. Procedure codes in Epic.EAP.ID. |

| Results | 30954-2: Relevant diagnostic tests/laboratory data Narrative | Results of laboratory tests. Sorted by time. Up to 200 results per patient. |

| Encounter Summary | ||

| Patient information | Same as above | |

| Reason for Visit | 29299-5: Reason for visit 8661-1: Chief Complaint | Reason for visit, specialty, diagnosis/procedures, provider referred (by and to). |

| Encounter Details | 46240-8: History of encounters | Encounter date, type, department, location, care team. |

| Social History | 29762-2: Social history Narrative | Tobacco use (including packs/day, years used), alcohol use (including drinks/week, oz/week), sex assigned at birth, occupation (including job start date, industry), travel history. Codes in SNOMED-CT and LOINC. |

| Last Filed Vital Signs | 8716-3: Vital signs | Blood pressure, pulse, temperature, respiratory rate, oxygen saturation, height, weight, body mass index. |

| Progress Notes | 10164-2: History of Present Illness | Sharing of progress notes is not supported in DSTU2. |

| Anesthesia Record | 59774-0: Anesthesia Records | Anesthesia records, date, provider. |

| Medications at Time of Discharge | 10183-2: Hospital Discharge Medications 75311-1: Discharge Medications | Medications, Signatura, amount dispensed, date, and author. Drug codes in but not limited to RxNorm. |

| Plan of Treatment | 18776-5: Plan of care note | Date, type, specialty, and care team of upcoming encounter. |

| Patient Instructions | 61146-7: Instructions | Provider instructions during the encounter. |

| Discharge Instructions | 8653-8: Discharge Instructions | Provider instructions at discharge and patient education. |

| Goals | 61146-7: Goals | Goals of the encounter. |

| Procedures | 47519-4: History of Procedures Document | Relevant procedures. |

| Results | 30954-2: Relevant diagnostic tests/laboratory data Narrative | Relevant test results. |

| Visit Diagnoses | 51848-0: Assessments | Diagnoses associated with the encounter. |

| Administered Medications | 29549-3: Medications administered | Medications, Signatures, action dates, and author. |

Shown below are available FHIR data for breast cancer risk calculation and additional relevant clinical variables for each patient advocate and in total (Table 4). Among those variables required for risk calculation, variables with documentation in the majority of advocates were age (100%), race/ethnicity (67%), history of benign breast biopsy and number of breast biopsies (67%), and mammographic breast density (67%). Only one-third of advocates had documentation of family history including first- or second-degree relative with breast cancer and relative with ovarian cancer, male breast cancer, or bilateral breast cancer, and none had documentation of Ashkenazi descent or reproductive factors including age at menarche and age at first live birth. While one (17%) had documentation of a history of atypical hyperplasia, no patient advocate had available breast pathology reports. One advocate (Patient Advocate #1) had sufficient data from the FHIR XML files to calculate risk using the BCSC model, but no patient advocate had sufficient data to calculate risk using the Gail model or BRCAPRO.

Table 4.

Available FHIR data for relevant clinical variables for each patient advocate and in total. An X denotes that documentation of a variable was found in XML files for that individual “Continued”.

| Variable | Patient Advocate | Total | ||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |||

| Necessary for Risk Calculation | ||||||||

| Age | X | X | X | X | X | X | 100% (6/6) | |

| Race/Ethnicity | X | X | X | X | 67% (4/6) | |||

| History of benign breast biopsy | X | X | X | X | 67% (4/6) | |||

| Number of breast biopsies | X | X | X | X | 67% (4/6) | |||

| Mammographic density | X | X | X | X | 67% (4/6) | |||

| First-degree relative with breast cancer | X | X | 33% (2/6) | |||||

| Second-degree relative with breast cancer | X | X | 33% (2/6) | |||||

| Relative with ovarian cancer, male breast cancer, or bilateral breast cancer | X | X | 33% (2/6) | |||||

| History of atypical hyperplasia | X | 17% (1/6) | ||||||

| Breast pathology reports available | 0% (0/6) | |||||||

| Age at first menstrual period | 0% (0/6) | |||||||

| Age at first live birth | 0% (0/6) | |||||||

| Ashkenazi Jewish descent | 0% (0/6) | |||||||

| Additional Relevant Variables | ||||||||

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | X | X | X | X | X | X | 100% (6/6) | |

| Systolic and diastolic blood pressure | X | X | X | X | X | X | 100% (6/6) | |

| Alcohol use | X | X | X | 50% (3/6) | ||||

| Breast ultrasound | X | X | X | 50% (3/6) | ||||

| Chemoprevention use | X | X | 33% (2/6) | |||||

| Use of oral contraceptives | X | 17% (1/6) | ||||||

| Smoking history | X | 17% (1/6) | ||||||

| Cardiovascular risk factors | X | 17% (1/6) | ||||||

| Bilateral mastectomy | X | 17% (1/6) | ||||||

| Menopausal status | X | 17% (1/6) | ||||||

| Family history of non-breast cancers | X | 17% (1/6) | ||||||

| Breast magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) | X | 17% (1/6) | ||||||

| Bone density scan (DEXA) | X | 17% (1/6) | ||||||

| FSH, LH, estradiol | X | 17% (1/6) | ||||||

| Age at menopause | 0% (0/6) | |||||||

| Number of live births | 0% (0/6) | |||||||

| Use of hormone replacement therapy | 0% (0/6) | |||||||

| Hysterectomy and/or oophorectomy | 0% (0/6) | |||||||

| Osteoporosis or osteopenia | 0% (0/6) | |||||||

| Endometrial cancer | 0% (0/6) | |||||||

| History of venous or arterial thrombosis, pulmonary embolism | 0% (0/6) | |||||||

| Drug use | 0% (0/6) | |||||||

| Genetic counseling notes | 0% (0/6) | |||||||

| Germline genetic testing reports | 0% (0/6) | |||||||

Among relevant (but not required) clinical variables, all advocates (100%) had documentation of blood pressure as well as height and weight for calculation of BMI. Half of advocates had breast ultrasound reports, and one had a breast MRI report. The remainder of variables had documentation in one or no advocate. For example, while one advocate had documentation of menopausal status, none had age of menopause or number of live births documented. No advocate had a genetic testing results report or a genetic counseling note.

Discussion:

We evaluated whether the FHIR standard could support automated breast cancer risk calculations in RealRisks using data downloaded for six patient advocates. While only one patient advocate had sufficient information for risk calculation using the BCSC model and none had complete information for risk calculation using the Gail or BRCAPRO models, we found that the majority of advocates had documentation of age, race/ethnicity, prior breast biopsy, and mammographic density. We also found additional data, including vital signs (blood pressure, BMI) and coexisting medical conditions, that would be relevant to patient-provider discussions and decision-making regarding chemoprevention and risk-reducing measures.

To our knowledge, our group is the first to investigate the use of the FHIR API to enhance and automate breast cancer risk calculation. Our current project represents our initial attempts to locate relevant patient data in downloads from the FHIR API, and even with a small sample size of only six patients, demonstrates that data for variables including breast pathology, breast imaging, vital signs, and race/ethnicity can be successfully found in FHIR downloads. We previously demonstrated that there was moderate agreement between information on breast cancer risk extracted from the EHR compared to patient self-report30, and also found that while self-report identifies more women who are potentially eligible for chemoprevention or genetic testing for hereditary breast and ovarian cancer (HBOC) based upon family history, more specific information on breast pathology or mammographic density can be obtained from the EHR30,31.

In this study, certain categories of patient data, particularly gynecologic history, family history of cancer, and history of genetic counseling and testing, were documented less frequently than other data types or not at all. This is consistent with our previous finding that family history is better represented in self-report than EHR data, but also highlights the limitations of using EHR data alone in risk calculation, with the potential for missing or inaccurate data32-34. The presence of information is dependent on documentation by providers in the EHR, which often does not include regular documentation of pertinent negative history (for example, that a patient does not have a family history of breast cancer) and also varies based upon individual providers’ scope of practice. Some missing data can also be explained by current gaps in FHIR coverage. For example, FHIR DSTU2 does not support sharing progress notes, and gynecologic history and family history are often present free-text in progress notes and not in structured data. FHIR R4 is anticipated to provide this coverage, but R4 support for progress notes was not available at the time of our study. However, an important consideration is that much of the information required for adequate and accurate risk assessment, if present, is dispersed throughout patients’ medical charts, recorded by multiple providers in different places such as progress notes and mammography reports and in both structured and unstructured form35. Finding such data requires approaches that search for free-text within notes and other documents, in addition to structured data such as billing codes.

One potential solution for automated risk calculation in our RealRisks and BNAV decision support tools is to incorporate both self-reported data and data automatically populated using the FHIR API, with the goal of harnessing the strengths of each approach. We plan to update RealRisks to automatically populate the necessary patient information for risk calculation, with a screen that shows this data to patients with a request to review and modify data before running the risk assessments. This will allow for patients to add any missing data and correct erroneous data, with the goal of making the process faster and more accurate. If feasible, an ultimate goal is to store this semi-automated, patient-corrected risk information and return to the EHR for ongoing use by providers; given that our work is still in early stages, we have not yet implemented this. In future, we also plan to develop a screen for both patients and providers to review automatically populated additional medical history that would be relevant to shared decision-making about breast cancer risk reduction with chemoprevention, testing for susceptibility genes, screening and other preventive strategies. While a personalized approach to prevention or early detection of breast cancer has emerged as a highly promising strategy, several barriers exist including the time required to conduct risk assessment of each women in a population36. Presenting a summary of auto-populated relevant history to the provider could save time during patient encounters and enhance discussions and recommendations about personalized screening and prevention options, which could overcome some barriers to increasing the uptake of underutilized breast cancer prevention services.

We are currently evaluating RealRisks and BNAV in a randomized controlled trial among women with high-risk breast lesions (atypical hyperplasia, lobular or ductal carcinoma in situ); patients and their providers will be randomized to have access to these tools plus standard educational materials versus standard educational materials alone, and the frequency of chemoprevention informed choice will be compared at six months37. Given that the majority of participating sites in this trial use Epic, we anticipate that we will have access through the RealRisks SMART on FHIR add-on to many participants’ EHR data, and therefore we plan to implement our automated risk calculation method described above to evaluate usability among a larger cohort of women. In particular, this trial will allow us to evaluate the accuracy of the EHR data pulled from FHIR through comparison with breast cancer risk data that is manually entered by the study team at time of patient enrollment. In addition, our data parsing during this initial study was more time-intensive given that we sought to locate data within the downloaded data files, but we will next use natural language-processing methods to parse unstructured data from progress notes, particularly to automatically extract family history.

Strengths of our study, as stated above, include its innovative approach to meet the unmet clinical need of automating breast cancer risk calculations utilizing FHIR data, as well as our creation of a multidisciplinary team including medical oncologists, biomedical informaticists, and software developers to best inform our study questions and approach. A major limitation is its small sample size of only six patients, of whom all were patient advocates known to the study team; this likely introduced bias into the type of data variables that would be found (or missing) in the downloaded files, and therefore might limit the generalizability of our findings. However, this study represented an initial analysis of the feasibility of using FHIR to obtain breast cancer risk factors from the EHR, and further evaluation of our methods using a larger population in a prospective clinical trial will overcome these limitations.

Conclusion:

We were able to identify relevant patient data in FHIR that could be incorporated into automated breast cancer risk calculation in the RealRisks and BNAV decision support tools. We will next evaluate an automated risk calculation method incorporating patient EHR data from FHIR as part of an ongoing prospective clinical trial among patients at high risk for developing breast cancer.

Acknowledgements:

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH), National Cancer Institute (NCI) R01CA177995 R01CA226060 (S1904), P30 CA013696; an American Cancer Society (ACS) Research Scholar Grant RS G-17-103-01; and a National Library of Medicine Biomedical Informatics Training Award T15 LM007079-29. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Figures & Table

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fuchs HE, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2021. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71:7–33. doi: 10.3322/caac.21654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.DeSantis CE, Ma J, Gaudet MM, et al. Breast cancer statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin. 2019;69:438–51. doi: 10.3322/caac.21583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wickerham DL, Costantino JP, Vogel VG, et al. The use of tamoxifen and raloxifene for the prevention of breast cancer. Recent Results Cancer Res. 2009;181:113–9. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-69297-3_12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cuzick J, Sestak I, Cawthorn S, et al. Tamoxifen for prevention of breast cancer: Extended long-term follow-up of the ibis-i breast cancer prevention trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16:67–75. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)71171-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vogel VG, Costantino JP, Wickerham DL, et al. Update of the national surgical adjuvant breast and bowel project study of tamoxifen and raloxifene (star) p-2 trial: Preventing breast cancer. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2010;3:696–706. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-10-0076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goss PE, Ingle JN, Alés-Martínez JE, et al. Exemestane for breast-cancer prevention in postmenopausal women. New England Journal of Medicine. 2011;364:2381–91. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1103507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cuzick J, Sestak I, Forbes JF, et al. Anastrozole for prevention of breast cancer in high-risk postmenopausal women (ibis-ii): An international, double-blind, randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2014;383:1041–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62292-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Allred DC, Anderson SJ, Paik S, et al. Adjuvant tamoxifen reduces subsequent breast cancer in women with estrogen receptor–positive ductal carcinoma in situ: A study based on nsabp protocol b-24. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2012;30:1268–73. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.34.0141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Breast cancer screening and diagnosis (version 1.2020) at https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/breast-screening.pdf.)

- 10.Saslow D, Boetes C, Burke W, et al. Vol. 57. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians; 2007. American cancer society guidelines for breast screening with mri as an adjunct to mammography; pp. 75–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Monticciolo DL, Newell MS, Moy L, Niell B, Monsees B, Sickles EA. Breast cancer screening in women at higher-than-average risk: Recommendations from the acr. Journal of the American College of Radiology. 2018;15:408–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2017.11.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ropka ME, Keim J, Philbrick JT. Patient decisions about breast cancer chemoprevention: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2010;28:3090–5. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.27.8077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bober SL, Hoke LA, Duda RB, Regan MM, Tung NM. Decision-making about tamoxifen in women at high risk for breast cancer: Clinical and psychological factors. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2004;22:4951–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.05.192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Melnikow J, Paterniti D, Azari R, et al. Preferences of women evaluating risks of tamoxifen (power) study of preferences for tamoxifen for breast cancer risk reduction. Cancer. 2005;103:1996–2005. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaplan CP, Haas JS, Pérez-Stable EJ, Des Jarlais G, Gregorich SE. Factors affecting breast cancer risk reduction practices among california physicians. Prev Med. 2005;41:7–15. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.09.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Salant T, Ganschow PS, Olopade OI, Lauderdale DS. "Why take it if you don't have anything?" Breast cancer risk perceptions and prevention choices at a public hospital. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:779–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00461.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Costantino JP, Gail MH, Pee D, et al. Validation studies for models projecting the risk of invasive and total breast cancer incidence. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999;91:1541–8. doi: 10.1093/jnci/91.18.1541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tice JA, Bissell MCS, Miglioretti DL, et al. Validation of the breast cancer surveillance consortium model of breast cancer risk. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2019;175:519–23. doi: 10.1007/s10549-019-05167-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Berry DA, Iversen ES, Jr, Gudbjartsson DF, et al. Brcapro validation, sensitivity of genetic testing of brca1/brca2, and prevalence of other breast cancer susceptibility genes. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:2701–12. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.05.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kukafka R, Yi H, Xiao T, et al. Why breast cancer risk by the numbers is not enough: Evaluation of a decision aid in multi-ethnic, low-numerate women. J Med Internet Res. 2015;17:e165. doi: 10.2196/jmir.4028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Coe AM, Ueng W, Vargas JM, et al. Usability testing of a web-based decision aid for breast cancer risk assessment among multi-ethnic women. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2016;2016:411–20. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kukafka R, Fang J, Vanegas A, Silverman T, Crew KD. Pilot study of decision support tools on breast cancer chemoprevention for high-risk women and healthcare providers in the primary care setting. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2018;18:134. doi: 10.1186/s12911-018-0716-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fhir overview. (Accessed February 28, 2021, at https://www.hl7.org/fhir/overview.html.)

- 24.Cms interoperability and patient access final rule (cms-9115-f) 2020 at https://www.cms.gov/files/document/cms-9115-f.pdf.)

- 25.Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology (ONC) Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology at the Department of Health and Human Services; 21st century cures act: interoperability, information blocking, and the onc health it certification program. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zong N, Wen A, Stone DJ, et al. Developing an fhir-based computational pipeline for automatic population of case report forms for colorectal cancer clinical trials using electronic health records. JCO Clin Cancer Inform. 2020;4:201–9. doi: 10.1200/CCI.19.00116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gulden C, Blasini R, Nassirian A, et al. Prototypical clinical trial registry based on fast healthcare interoperability resources (fhir): Design and implementation study. JMIR Med Inform. 2021;9:e20470. doi: 10.2196/20470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Garza MY, Rutherford M, Myneni S, et al. Evaluating the coverage of the hl7® fhir® standard to support esource data exchange implementations for use in multi-site clinical research studies. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2020:472–81. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kuchenbaecker KB, Hopper JL, Barnes DR, et al. Risks of breast, ovarian, and contralateral breast cancer for brca1 and brca2 mutation carriers. JAMA. 2017;317:2402–16. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.7112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jiang X, McGuinness JE, Sin M, Silverman T, Kukafka R, Crew KD. Identifying women at high risk for breast cancer using data from the electronic health record compared with self-report. JCO Clin Cancer Inform. 2019;3:1–8. doi: 10.1200/CCI.18.00072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sin M, McGuinness JE, Trivedi MS, et al. Automatic genetic risk assessment calculation using breast cancer family history data from the ehr compared to self-report. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2018;2018:970–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Patel N, Miller DP, Jr, Snavely AC, et al. A comparison of smoking history in the electronic health record with self-report. Am J Prev Med. 2020;58:591–5. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2019.10.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kharrazi H, Wang C, Scharfstein D. Prospective ehr-based clinical trials: The challenge of missing data. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29:976–8. doi: 10.1007/s11606-014-2883-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Polubriaginof FCG, Ryan P, Salmasian H, et al. Challenges with quality of race and ethnicity data in observational databases. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2019;26:730–6. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocz113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Payne TH, Zhao LP, Le C, et al. Electronic health records contain dispersed risk factor information that could be used to prevent breast and ovarian cancer. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2020;27:1443–9. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocaa152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pashayan N, Antoniou AC, Ivanus U, et al. Personalized early detection and prevention of breast cancer: Envision consensus statement. Nature Reviews Clinical Oncology. 2020;17:687–705. doi: 10.1038/s41571-020-0388-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Crew KD, Silverman TB, Vanegas A, et al. Study protocol: Randomized controlled trial of web-based decision support tools for high-risk women and healthcare providers to increase breast cancer chemoprevention. Contemp Clin Trials Commun. 2019;16:100433. doi: 10.1016/j.conctc.2019.100433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]