Abstract

With rates of tobacco use among youth in the United States on the rise, further analysis of disproportionately impacted populations, like Native Hawaiian and other Pacific Islanders (NHPIs), is needed. NHPIs face a unique set of challenges compared to other ethnic minorities that contribute to their health disparities from tobacco use. This systematic literature review investigated empirical studies published between 2010–2020 on tobacco use among NHPI youth and young adults. Using comprehensive literature search engines and focused author searches of tobacco researchers in NHPI communities, 7,208 article abstracts were extracted for potential inclusion. Explicit inclusionary and exclusionary criteria were used to identify peer-reviewed articles related to tobacco use correlates and interventions for NHPI youth populations. A total of 17 articles met our criteria for inclusion in this study. Community influences, peer pressure, social status, variety of flavors, craving, and stimulation were correlates found in smoking and vaping for NHPI youth. There were also few published tobacco use prevention and intervention studies focused specifically on NHPI youth. Our study addresses the needs of an under-researched population that is heavily affected by the adverse consequences of short-term and long-term use of cigarettes and e-cigarettes. Additional research should focus on developing effective and culturally relevant interventions to reduce NHPI health disparities.

Keywords: tobacco, smoking, cigarettes, e-cigarettes, Native Hawaiian, Pacific Islanders

According to a report published by the United States Surgeon General, combustible cigarette use among U.S. adults fell from nearly 50% to less than 20% between 1964 and 2013 (National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (US) Office on Smoking and Health, 2014). That percentage dropped even lower to 13.7% in 2018 (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2019). Although combustible cigarette use in the United States has been decreasing over time, the emergence of electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes) and the rising prevalence of other nicotine products has caused smoking rates to spike in recent years (Cullen et al., 2018). Further, little is known regarding the impact of increased availability and choice of tobacco and nicotine products on diverse youth populations. A systematic literature review including Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders (NHPIs), for example, found them to have higher smoking prevalence rates than other major ethnic groups in Hawai‘i (Kim et al., 2007). However, because Kim et al.’s findings predated the increase in the use of electronic nicotine delivery systems (including e-cigarettes), an updated examination of the state of the science focused on NHPI youth tobacco use is needed to address smoking and related health disparities (e.g., cancer and cardiovascular disease) of NHPI populations.

The purpose of this study is to systematically examine the recent published scientific literature related to tobacco use among NHPI youth and young adults. This study examined published literature from 2010–2020 targeting Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander youth across the United States and The United States Affiliated Pacific Islands (USAPI). The latter region encompasses Guam, the Federated States of Micronesia (FSM; Pohnpei, Kosrae, Chuuk, and Yap), and the Marshall Islands. Using a set of discrete inclusionary and exclusionary criteria, we identified and analyzed studies focused on determinants of tobacco use and interventions focused on preventing tobacco use for NHPI youth and young adults. Implications for culturally-focused tobacco prevention interventions are discussed.

Literature Review

Health Effects of Youth Tobacco Use: A Contemporary Perspective

In addition to the widely known health issues associated with smoking, new injuries and illnesses are being identified in association with e-cigarette use. Not only are e-cigarette users at risk for lung cancer, cardiovascular disease, and respiratory illness, but those who partake in vaping are at risk for lipoid pneumonia, bronchiolitis obliterans, primary spontaneous pneumothorax, and on rare occasion, exploding vape pen devices (Broderick, 2021; United States Food and Drug Administration, 2020). The COVID-19 pandemic of 2020–2021 has exposed a new concern regarding cigarette and e-cigarette use among youth. According to Gaiha et al. (2020), adolescent e-cigarette and dual-users are 5 and 7 times more likely to be diagnosed with COVID-19, respectively. This evidence suggests that e-cigarette and combustible cigarette users are more at risk of contracting COVID-19 than their non-smoking peers. Additionally, due to the relatively recent emergence of vaping compared with combustible cigarettes, many long-term effects of vaping are still unknown.

Alarmingly, many youths who have not used combustible cigarettes have used e- cigarettes, which poses a significant problem (Boyle et al., 2019). Further, these youth have been found to have a greater risk of using combustible cigarettes later in their adolescence (Wills et al., 2017). Considered a safer alternative to combustible cigarette use among adult habitual smokers, e-cigarettes pose a health risk to youths and novice users by exposing them to high concentrations of nicotine and other harsh chemicals. Due to the e-cigarette epidemic, it is imperative to identify precursors for smoking onset and determine successful prevention programs before smoking becomes more normalized, especially for high-risk communities, such as NHPI populations.

The Sociocultural Context NHPI Youth Tobacco Use

Several studies have shown that the social and relational context within NHPI communities influence substance use. Specifically, close, interconnected relational networks of NHPI youth comprised of cousins and adult extended family members in their communities have been found to encourage and discourage tobacco use (Okamoto et al., 2009, 2010, 2014; Pokhrel et al., 2019). Studies have also suggested that NHPI youth who receive higher scores on stress and hostility tests are more likely to be heavy smokers. For example, there is a clear correlation between Samoan male young adults with high-stress levels and heavy smoking (Rainer et al., 2019). More research is necessary to examine the culturally specific risk and protective factors for NHPI youth populations. Identifying these factors may provide guidance toward developing more effective prevention and cessation programs for these youth.

The sociohistorical and rural contexts of NHPIs have also served as unique risk factors that exacerbate health disparities. For example, NHPIs have experienced historical trauma passed down from generation to generation, often resulting in socio-economic hardship and drug use in their communities (Chen et al., 2014; Pokhrel & Herzog, 2014; Wills et al., 2013). Cultural and historical trauma as a result of forced colonization has been related to the increased likelihood of poorer mental health and tobacco, drug, and alcohol abuse (Pokhrel & Herzog, 2014). High concentrations of Native Hawaiians reside in rural areas in Hawai‘i, and are simultaneously exposed to elevated ecological risks for use of tobacco and other substances (Okamoto et al., 2014). Despite these risks, there is a lack of intervention and treatment options for Native Hawaiian youth, particularly for those in rural communities in Hawai‘i (Okamoto et al., 2010).

Relevance and Purpose of the Study

Recent surveillance data has indicated the need to understand tobacco use of NHPI youth. For example, 18% of all middle school youth in the state of Hawai‘i currently use an electronic vapor product, ranking first nationally among all states collecting data on middle school youth (CDC, 2020). Of these youth, 30% are of Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander ancestry, representing the highest percentage of e-cigarette users among major ethnic groups in Hawai‘i. Despite these emerging trends, the most recent review of the state of the science related to NHPI tobacco use was published prior to the emergence of the e-cigarette epidemic (Kim et al., 2007). Kim et al’s systematic literature review found elevated smoking rates for Native Hawaiian, Pacific Islander, and Filipino youth compared to other ethnic groups in Hawai‘i. However, because they primarily included studies that aggregated NHPI youth with Asian American youth in their review, their study lacked an in-depth examination of NHPI-specific findings. Their review also pre-dated the emergence of literature focused on e-cigarette use. A current understanding of smoking and tobacco use patterns in NHPI youth populations will lead to more effective and culturally relevant prevention and intervention programs for these youth.

Thus, the purpose of this study is to examine the state of the science related to tobacco use of NHPI youth and young adults residing in the United States and United States Affiliated Pacific Islands (USAPI). Using established procedures for systematic literature reviews, we examined literature focused on the correlates of tobacco use for NHPI youth and young adults, as well as published interventions that have addressed NHPI tobacco use. The present study provides a needed update to the Kim et al. (2007) review, and has implications for culturally relevant interventions for NHPI youth populations.

Methods

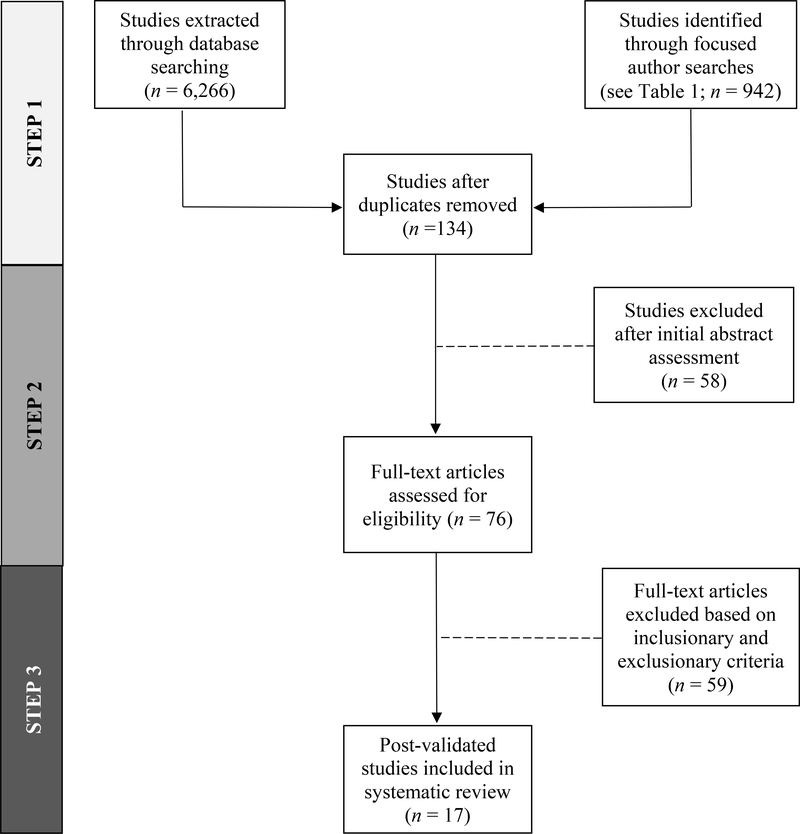

Figure 1 illustrates our systematic literature search and review processes. In Step 1, articles were found through PubMed, PsycNet (both PsycArticles and PsycInfo), and a focused author search on Google Scholar (see Table 1). The latter search method was used to identify articles that may have been overlooked using library literature search engines and to validate the articles included in this review that were identified using these search engines. Our primary database search terms were “Native Hawaiian and/or Pacific Islander,” “Asian American and Pacific Islander,” and “tobacco”. During these broader searches, we used additional search terms—“smoking,” “nicotine,” “cigarette,” “e-cigarette,” “vape,” “vaping,” “JUUL,” “hookah,” and “betel nut” (if it contained nicotine)—in order to refine the search perimeter. Authors were selected for our focused author search, due to their high research productivity in the areas of tobacco use, Asian Americans, Native Hawaiians and/or Pacific Islanders. The online database search yielded a total of 6,266 studies and the focused author search yielded a total of 942 studies (7,208 total). After eliminating duplicate studies from multiple databases and the focused author search, there were 134 unique studies for potential inclusion in this review. In Step 2, the primary authors (MHR, DLJ, and KSM) reviewed the abstracts of the remaining studies from this initial search, to determine whether they focused on our primary investigative constructs (i.e., a focus on Native Hawaiian and/or Pacific Islander youth and tobacco product use). Fifty-eight studies were excluded after an initial assessment of the abstracts.

Figure 1.

PRISMA Flow Diagram for Literature Review. This figure illustrates our process for identifying and reducing the number of articles included this review, in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) Statement.

Table 1.

Focused Author Searches: 2010–2020

| Author | Number of Articles |

|---|---|

| Cassel, Kevin | 10 |

| Clark, Trenette T. | 35 |

| Hofstette, Richard C. | 17 |

| Huh, Jimi | 53 |

| Kim, Seo-Ryung | 146 |

| Leventhal, Adam | 68 |

| Maxwell, Annette E. | 52 |

| Moon, Sung Seek | 246 |

| Pokhrel, Pallav | 50 |

| Rogers, Christopher J. | 4 |

| Subica, Andrew M. | 28 |

| Tanjasiri, Sora Park | 15 |

| Unger, Jennifer B. | 128 |

| Wills, Thomas A. | 30 |

| Zhu, Shu-Hong | 60 |

| Total | 942 |

In Step 3, the full text of the 76 remaining articles were examined by the primary authors for potential inclusion in the study, by applying a discrete set of inclusionary and exclusionary criteria. Articles were included in this review if they met the following criteria—(1) they reported empirical findings (i.e., qualitative, quantitative, or mixed-methods findings); (2) they were published between 2010–2020; (3) the samples in the study were drawn from the United States or the USAPI; (4) they included at least 20% of NHPIs in their study samples; and (5) the age of the study samples were less than or equal to 29 and/or had a mean age of 29. Articles were excluded in this review, if (1) the study sample included less than 20% of NHPIs; (2) the study did not specifically examine tobacco product use; (3) the study was published prior to 2010; (4) the study was not peer-reviewed; and (5) the study focused on non-human samples. The primary authors excluded 59 articles based on the inclusionary and exclusionary criteria of this study. As a result, 17 empirical articles meeting the criteria were included in this systematic review.

Results

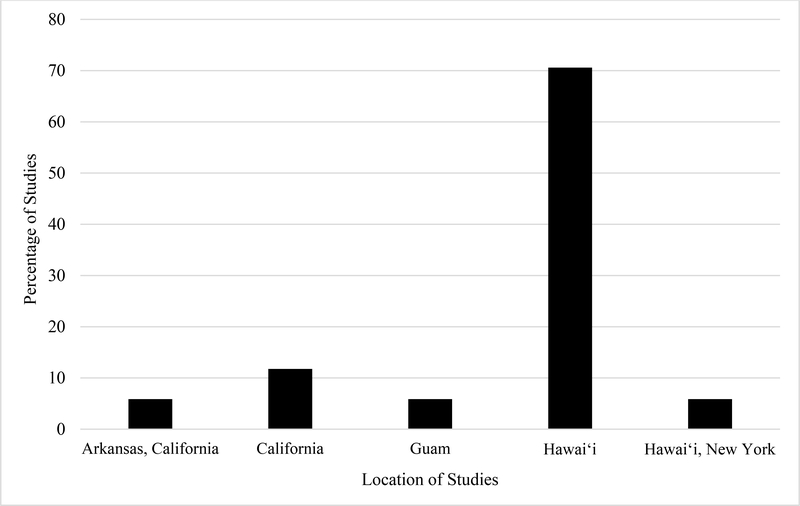

Table 1 describes the 17 studies included in this review. Two of these studies (11.8%) examined prevention interventions and the remaining 15 (88.2%) examined correlates of combustible cigarette, e-cigarette, or generalized tobacco use. Quantitative (n = 13; 76.4%), qualitative (n = 1; 5.8%) and mixed methods (n = 3; 17.6%) were identified from our search. Research participants resided in the coastal regions of the Continental U.S. (California and/or New York; n = 4, 29%) and in Hawai‘i (n = 12; 70.5%; See Figure 2). Eight separate first authors were identified in the studies included in this review—Pokhrel (n = 6; 35.3%), Wills (n = 3; 17.6%), Okamoto (n = 3; 17.6%), Rainer (n = 1; 5.9%), Yang (n = 1; 5.9%), Subica (n = 1; 5.9%), Mitschke (n = 1; 5.9%), and Lee (n = 1; 5.9%).

Figure 2.

Percentage of Studies by Location

Social and Attitudinal Correlates

Of the 17 studies, the majority covered social and community-based factors, and were focused on Native Hawaiian youth. For example, Native Hawaiian youth had access to tobacco frequently, even when they were not seeking it, and experienced peer pressure (Okamoto et al., 2014; Wills et al., 2013). Lack of support from family members, lower education from parents, and conflict within the household were found to increase Native Hawaiian youths’ willingness to smoke/vape (Pokhrel et al., 2020; Wills et al., 2016; Wills et al., 2017). Samoan and Marshallese youth were the second most studied ethnic groups in this review. Samoan young adults who were heavy smokers scored higher in psychosocial factors, such as hostility and stress within their community (Rainer et al., 2019). Similarly, youth in Guam were 4–5 times more likely to use tobacco than their counterparts in the U.S. due to social influences (Pokhrel et al., 2019). The latter study was the only study to correlate nicotine use with betel nut use.

Studies that examined the ecological context of tobacco users revealed that social relationships were complicated and often heavily influenced youths’ tobacco use. For example, Okamoto et al. (2010), found that girls were offered gateway drugs (including tobacco) more often and found it more difficult to refuse these offers. This may be due to the cultural fear of damaging social relationships by refusing offers by friends and family members to use substances. In a related study, it was found that Native Hawaiian youth had higher exposure to drug offers than non-Hawaiian counterparts. Familial relationships, peer pressure, and unexpected offers to use drugs within their communities may have resulted in higher exposure to tobacco usage (Okamoto et al., 2014). Interestingly, according to Pokhrel et al. (2016), in Native Hawaiian communities, high levels of social support were correlated with low levels of tobacco use, but high frequencies of interaction within the community resulted in feelings of low social support, demonstrating the complexity of relationships within Native Hawaiian communities. Additionally, conflicting qualitative narratives were found when youth were asked about tobacco exposure and acceptance within families. Some youth reported that they were consistently exposed to tobacco by family members, but that those same family members would advise them against smoking. Further, Native Hawaiian youth described the interconnected network of relationships within their communities that served to intensify tobacco use risk and protection. Some feared their parents and other caregivers would be told if they were seen smoking by other family members (Okamoto et al., 2010). These fears were often enough to delay or prevent smoking onset due to the negative reaction anticipated from elders.

Within NHPI populations, e-cigarette use was correlated with the perception of safety compared to combustible cigarettes, desirable flavors, benefits related to vapor instead of smoke, recreational activities, social influence, and positive expectancies (Pokhrel, Herzog, Muranaka, & Fagan, 2015; Pokhrel, Herzog, Muranaka, Regmi, & Fagan, 2015; Wills et al., 2017; Wills et al., 2016; Subica et al., 2020). Young users are more attracted to the sensory stimulation of e-cigarettes compared to combustible cigarettes, and consider e-cigarette use to be consistent with healthy lifestyle activities, such as going to the gym (Pokhrel, Herzog, Muranaka, & Fagan, 2015). However, the onset of e-cigarette use also appears to be a gateway into youths’ smoking of combustible cigarettes when they otherwise would have been low risk (Wills et al., 2016; Wills et al., 2017, Yang et al., 2013). Dual use of e-cigarettes and combustible cigarettes was found to be common due to e-cigarettes being more socially acceptable in public settings (Pokhrel, Herzog, Muranaka, Regmi, & Fagan, 2015).

Intervention Studies

Intervention studies focused on increasing awareness and education of tobacco use while also promoting adaptive alternatives to stress-induced situations, like family or peer conflict. There were two studies identified in this review, both of which were prevention studies that took place in Hawai‘i (Mitschke et al., 2010; Okamoto et al., 2019). Mitschke et al. examined the effects of anti-tobacco drama performances in Native Hawaiian, Samoan, Tongan, and Marshallese participants. They found a decrease in youth that were vulnerable to becoming smokers and an increase in knowledge of drug addiction. Okamoto et al. evaluated a culturally grounded curriculum that focused primarily on gateway drug use, and included content on cigarette and e-cigarette use. They found that youth exposed earlier to the curriculum had a slower growth in cigarette and e-cigarette use over time, supporting the efficacy of the curriculum for tobacco prevention.

Discussion

This study systematically reviewed the empirical literature focused on Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander tobacco use. The findings indicated that there were multiple sociocultural and psychosocial influences affecting NHPI youth tobacco use, such as familial and peer influences, social pressure, stress relief, and perceived health benefits. Intervention programs directly addressed NHPI cultural context, and have shown modest, positive effects. However, much of this research has been geographically isolated to Hawai‘i and coastal regions of the Continental U.S. Within these regions, there are concentrations of NHPI youth within both rural and urban communities whose tobacco use behaviors are strongly influenced by their social context, particularly close relational networks of biological and ascribed family members (Bills et al., 2016; Okamoto et al., 2009). These social and relational networks are uniquely associated with NHPI youth tobacco use across studies in this review.

While the regional focus of studies included in this review elucidates the area of NHPI tobacco use, it is important to note that the diaspora of Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders is widespread. Much remains unknown regarding tobacco use in communities with high concentrations of NHPIs across many regions of the Continental U.S., such as FSM communities in Arkansas, PI communities in Nevada and Arizona, and NHPI communities in Utah and Washington. Further, with only one identified tobacco use study within the USAPI (Pokhrel et al., 2019), much is still unknown about youth tobacco use within this region. According to the United States 2010 census, out of the 1,225,195 NHPI individuals within the United States, only 504,125 lived within Hawai‘i and California (Hixson et al., 2012). Thus, there appears to be a geographic disparity in tobacco research among NHPI communities, and additional research is necessary to address these knowledge gaps.

Since 2010, there has been an emergence of alternative methods of tobacco use that have impacted NHPI youth populations. E-cigarettes are an emerging method of tobacco use that has become prevalent in adolescents and young adults in recent years, and has disproportionately impacted NHPI youth. Researchers are only beginning to understand the effects of vaping on the lungs, and NHPI youths’ correlates to e-cigarette use. Further, the use of tobacco and betel nut in the USAPI is a unique regional and cultural phenomenon that needs further investigation. Addressing these gaps in knowledge will help to inform the foundation for culturally and regionally specific tobacco use interventions for NHPI youth populations.

Implications for Tobacco Interventions

This review provides guidance toward the development of culturally specific intervention programs for NHPI youth. The findings from the studies suggest that interventions should address the unique sociocultural and psychosocial influences impacting NHPI youth, including familial networks, peer networks, and social influences of NHPI youth. For example, a culturally grounded substance use prevention curriculum (Ho’ouna Pono) emphasized both a relational and skills-based approach to addressing substance use for rural Native Hawaiian youth (Okamoto et al., 2019). The goal of this program was to provide NHPI youth the skills to refuse tobacco offers, while simultaneously preserving relational harmony with parents, aunts/uncles, cousins and peers (Bills et al., 2016). Due to the close-knit, communal nature of NHPI communities, programs that intervene beyond the individual level may be most relevant (e.g. family-, community-, or school-based programs). Programs should also work toward providing normative education on tobacco use, including dispelling outdated perceptions of the health benefits of youths’ e-cigarette use that are pervasive within NHPI communities. At a broader level, these programs should work to complement existing population-based efforts, such as tobacco regulatory and policy approaches, in order to address tobacco disparities at multiple levels within NHPI communities.

Limitations of the Study

There were several limitations to this study. First, the findings were limited to the most recent 10-year time period. This decision was made to avoid overlap with a related systematic literature review (Kim et al., 2007), as well as to capture the bulk of e-cigarette and related research with NHPI youth. This may have left out studies relevant to NHPI youth prior to 2010 that were not captured in prior review articles. Second, unpublished (grey) literature was not included in this review. Historically, research focused on NHPI youth have had challenges in reaching publication, often due to perceptions that research with this population lacks scientific priority or generalizability (Okamoto, 2010). As a result, there may be several relevant studies that remain unpublished and/or are disseminated in smaller, regional outlets that may not have been captured in this review. Finally, articles that are in their early (pre-publication) stages may not have been captured in this review.

Conclusions

This study examined contemporary tobacco use of NHPI youth in the United States and USAPI. Sociocultural and psychosocial correlates were associated with smoking/vaping in NHPI adolescents and young adults. More research is needed with NHPI youth across a broader geographic range, in order to further understand the correlates to tobacco product use for these youth at a national level. This type of research would also help to inform culturally tailored smoking/vaping prevention, intervention, and cessation programs. Finally, much more culturally focused intervention research is necessary to address tobacco use disparities for NHPI youth.

Table 2.

Results of Systematic Literature Review

| Study | Age Range (M) | Region | Primary Ethnicities | Study Design | Sample Size (N) | Tobacco Type(s) | Study Focus | Description | Major Finding(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lee et al. (2019) | 12–19 | HI | CHUK, MARSH, SAMO | QUAN | 284 | TOB | COR | Examined the health implications related to biculturalism in PI communities. | Biculturalism indirectly leads to higher self-esteem which impacts different health aspects. Tobacco use risk was not directly impacted by self-esteem. Teaching the value of multiculturalism may have positive health benefits. |

| Mitschke et al. (2010) | 9–16 | HI | NH, SAMO, TONG, MARSH | MIX | 2142 | TOB | PREV | Evaluated an intervention model based on anti-tobacco drama performances of middle school AAPI youth. | Assessments indicated a statistically significant decrease in youth who thought they would become smokers within 5 years. It also showed a significant increase in the understanding of addiction. |

| Okamoto et al. (2010) | (11.9, 12.2) | HI | NH, PI | MIX | 194, 47 | CC | COR | Examined gender differences in drug-offer situations. | Girls were offered drugs more often and found it more difficult to refuse. This may be because of the cultural perspective of how refusal may harm the relationship. |

| Okamoto et al. (2014) | 11–12 | HI | NH, PI | QUAN | 249 | CC | COR | Examined NH vs non-NH differences in drug-offer situations. | NH youth had significantly higher rates of offers and drug usage than non-NH counterparts. Peer pressure, family drug offers, and unanticipated offers may have contributed to the higher usage. |

| Okamoto et al. (2019) | 10–13+ | HI | NH, PI | QUAN | 486 | E-CIG, CC | PREV | Evaluated a Culturally grounded, school-based prevention curriculum. | Small, significant reductions in CC, e-cigarette, and hard drug use were found in schools receiving the Ho‘ouna Pono curriculum, compared to comparison schools. |

| Pokhrel et al. (2014) | 18+ (27.5) |

HI | NH | QUAN | 128 | CC | COR | Examined discrimination, historical trauma, and substance use, including tobacco in NH populations. | Cigarette use was positively correlated with discrimination. Findings indicated an indirect path to higher substance use through perceived discrimination. Additionally, a direct path between historical trauma and lower substance use was found. |

| Pokhrel…Fagen (2015) | 18–35 (25.1) |

HI | NH | MIX | 62 | E-CIG | COR | Examined reasons ENDS users liked and disliked e-cigarettes. | Participants indicated 12 categories of reasons for liking and 6 categories of reasons for not liking e-cigarettes. Themes that arose included: perception of e-cigarettes’ safety, benefits related to vapor, attractive flavors, and recreational use. |

| Pokhrel...Regmi, & Fagan (2015) | 18–35 (25.1) |

HI | NH | QUAL | 62 | E-CIG, CC | COR | Examined the contexts regarding CC and e-cigarette use in dual users. | Participants expressed the following contexts surrounding their CC use: craving/stimulation, activities that trigger use, places, and other substance use. E-cigarette use included situations where CCs were not available or their usage was not permitted. |

| Pokhrel et al. (2016) | 18–35 (25.6) |

HI | NH | QUAN | 435 | CC | COR | Examined the relationship between smoking and social networks in AAPI groups | In NH, lower recent cigarette use was directly correlated with a large social network and high social support. High-frequency interaction with network members resulted in feelings of low social support in NH. |

| Pokhrel et al. (2019) | >18 | GU | CHAM | QUAN | 2449, 670 | TOB, E-CIG, CC |

COR | Examined risk, prevalence, and protective factors of tobacco use among youth in Guam. | Tobacco use in Guam is 4 to 5 times higher than in the U.S. Youth who had higher risk perceptions were less likely to use tobacco and betel nut. Social influence appears to be a correlate to nicotine and betel nut use. |

| Pokhrel et al. (2020) | 18–25 (21.2) |

HI | NH | QUAN | 2401 | CC | COR | Explored the relationship between CC and e-cigarette use with physical activity. | Higher moderate physical activity was significantly associated with reduced CC use at six-month mark. At follow-up, higher physical activity of all intensities was linked with heightened e-cigarette use. |

| Rainer et al. (2019) | 18–35 | CA | SAMO, TONG, NH, CHAM, MARSH | QUAN | 278 | CC | COR | Examined psycho-social factors that influence smoking in Tongan and Samoan communities. | Heavy smoking (HS) Samoan men had significantly higher stress, hostility, depression, and urgency scores. Samoan HS women had higher stress and hostility scores. Tongan women had higher sensation-seeking scores. Tongan men had no significant associations. |

| Subica et al. (2020) | 18–35 | CA, AR | SAMO, MARSH | QUAN | 143 | E-CIG | COR | Examined correlates of current e-cig use within PI communities. | Found a relationship between current marijuana use and current e-cig use. Also identified a relationship between e-cig use and positive expectations from e-cig use. Additional research is needed. |

| Wills et al. (2013) | (12.8, 13.5) |

NY, HI | NH, PI | QUAN | 601, 881 | TOB | COR | Tested dual-process model to determine substance use predictions in two diverse groups. | Good self-control had an inverse effect on substance use, including tobacco use. Poor emotional regulation had a risk-promoting effect on substance use. |

| Wills et al. (2016) | (14.7) | HI | NH, PI | QUAN | 2338 | E-CIG, CC | COR | Examined the relationship between e-cigarette use and future CC onset, in addition to predictors of e-cigarette onset. | E-cigarette users were more likely to begin using CCs. Older age, NH ethnicity, and rebelliousness were associated with smoking onset. Initiating e-cigarette use was associated with age, NH ethnicity, lower parent education and support, rebelliousness, and health perceptions. |

| Wills et al. (2017) | (14.7) | HI | NH | QUAN | 2309 | E-CIG, CC | COR | Explored the relationships between e-cigarette use, willingness to smoke CCs, and social-cognitive factors that predict smoking CCs. | Youth who used e-cigarettes were more willing to use CCs partially due to positive expectations regarding smoking. Conflict between parents and youth and parental monitoring were precursors to a willingness to smoking CCs. Future CC start was associated with willingness. |

| Yang et al. (2013) | 14–16 | HI | PI | QUAN | 1136 | E-CIG, CC |

COR | Studied assessed the difference between low-risk and high-risk youth regarding e-cigarette onset. | Risk factors for future CC use included e-cig use among never-smokers. Caucasian, Filipino, NH, and those from other backgrounds were at higher risk for smoking onset than AA. |

NOTE. Race/Ethnicity: AA = Asian American, AAPI = Asian American and Pacific Islander, NH = Native Hawaiian, SAM = Samoan, TONG = Tongan, CHAM = Chamorro, MARSH = Marshallese, CHUK = Chuukese, PI = Pacific Islander; Location: AR = Arkansas, CA = California, GU = Guam, HI = Hawai‘i, NY = New York; Study Design: QUAN = Quantitative, QUAL = Qualitative, MIX = Mixed Methods; Tobacco Type: TOB = Tobacco, E-CIG = Electronic Cigarettes, CC = Combustible Cigarettes; Study Focus: COR = Tobacco Use Correlates, PREV = Prevention

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by funding from the National Institutes of Health/National Institute on Drug Abuse (R34 DA046735; PI: Okamoto), National Institutes of Health/National Institute on General Medical Sciences (U01 GM138435; PI: Vakalahi), and the National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute (R01 CA228905, R01 CA202277; PIs: Pokhrel). The authors do not claim any conflicts of interests or competing interests in the publication of this study.

References

Studies included in this literature review are noted with an asterisk.

- Bills K, Okamoto SK, & Helm S (2016). The role of relational harmony in the use of drug refusal strategies of rural Native Hawaiian youth. Journal of Ethnic and Cultural Diversity in Social Work, 25(3), 208–226. 10.1080/15313204.2016.1146190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyle RG, Richter S, & Helgertz S (2019). Who is using and why: Prevalence and perceptions of using and not using electronic cigarettes in a statewide survey of adults. Addictive Behavior Reports, 10, 100227. 10.1016/j.abrep.2019.100227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broderick SR (2021). What does vaping do to your lungs? Johns Hopkins Medicine. https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/wellness-and-prevention/what-does-vaping-do-to-your-lungs

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019). Cigarette smoking among U.S. adults hits all-time low. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2019/p1114-smoking-low.html. [Google Scholar]

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020). 1995–2019 Middle School Youth Risk Behavior Survey Data. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. http://nccd.cdc.gov/youthonline/. [Google Scholar]

- Chen AC, Szalacha LA, & Menon U (2014). Perceived discrimination and its associations with mental health and substance use among Asian American and Pacific Islander undergraduate and graduate students. Journal of American College Health, 62(6), 390–398. 10.1080/15313204.2016.114619010.1080/07448481.2014.917648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cullen KA, Ambrose BK, Gentzke AS, Apelberg BJ, Jamal A, & King BA (2018). Notes from the field: Use of electronic cigarettes and any tobacco product among middle and high school students - United States, 2011–2018. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/67/wr/mm6745a5.htm?s_cid=mm6745a5_w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaiha SM, Cheng J, & Halpern-Felsher B (2020). Association between youth smoking, electronic cigarette use, and COVID-19. Journal of Adolescent Health, 67(4), 519–523. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.07.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hixson L, Hepler B, & Kim MO (2012, May). The Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander population: 2010. U.S. Department of Commerce Economics and Statistics Administration, U.S. Census Bureau. [Google Scholar]

- Kim SS, Ziedonis D, & Chen K (2007). Tobacco use and dependence in Asian American and Pacific Islander adolescents: A review of the literature. Journal of Ethnicity in Substance Abuse, 6(3), 113–142. 10.1300/J233v06n03_05 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Lee H, Lee HE, Cassel K, Hagiwara MI, & Somera LP (2019). Protective effect of biculturalism for health amongst minority youth: The case of Pacific Islander migrant youths in Hawai‘i. British Journal of Social Work, 49(4), 1003–1022. 10.1093/bjsw/bcz042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Mitschke D, Loebl K, Tatafu E, Matsunaga D, & Cassel K (2010). Using drama to prevent teen smoking: Development, implementation, and evaluation of crossroads in Hawai‘i. Health Promotion Practice, 11(2), 244–248. 10.1177/1524839907309869 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (US) Office on Smoking and Health. (2014). The health consequences of smoking—50 years of progress: A report of the Surgeon General. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Okamoto SK, Kulis SS, Helm S, Chin SK, Hata J, Hata E, & Lee A (2019). An efficacy trial of the Ho’ouna Pono drug prevention curriculum: An evaluation of a culturally grounded substance abuse prevention program in rural Hawai‘i. Asian American Journal of Psychology, 10(3), 239–248. 10.1037/aap0000164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto SK, Helm S, Po’a-Kekuawela K, Chin CI, & Nebre LR (2009). Community risk and resiliency factors related to drug use of rural Native Hawaiian youth: an exploratory study. Journal of Ethnicity in Substance Abuse, 8(2), 163–177. 10.1080/15332640902897081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto SK (2010). Academic marginalization? The journalistic response to social work research on Native Hawaiian youths. Social Work, 55(1), 93–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Okamoto SK, Kulis S, Helm S, Edwards C, & Giroux D (2010). Gender differences in drug offers of rural Hawaiian youths: A mixed-methods analysis. Affilia, 25(3), 291–306. 10.1177/0886109910375210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Okamoto SK, Kulis S, Helm S, Edwards C, & Giroux D (2014). The social contexts of drug offers and their relationship to drug use of rural Hawaiian youth. Journal of Child & Adolescent Substance Abuse, 23(4), 242–252. 10.1080/1067828X.2013.786937 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Pokhrel P, Dalisay F, Pagano I, Buente W, Guerrero E, & Herzog TA (2019). Adolescent tobacco and betel nut use in the US-affiliated Pacific Islands: Evidence from Guam. American Journal of Health Promotion, 33(7), 1058–1062. 10.1177/0890117119847868 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Pokhrel P, Fagan P, Cassel K, Trinidad DR, Kaholokula JK, & Herzog TA (2016). Social network characteristics, social support, and cigarette smoking among Asian/Pacific Islander young adults. American Journal of Community Psychology, 57(3–4), 353–365. 10.1002/ajcp.12063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Pokhrel P, & Herzog TA (2014). Historical trauma and substance use among Native Hawaiian college students. American Journal of Health Behavior, 38(3). 10.5993/AJHB.38.3.11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Pokhrel P, Herzog TA, Muranaka N, & Fagan P (2015). Young adult e-cigarette users’ reasons for liking and not liking e-cigarettes: A qualitative study. Psychology & Health, 30(12), 1450–1469. 10.1080/08870446.2015.1061129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Pokhrel P, Herzog TA, Muranaka N, Regmi S, & Fagan P (2015). Contexts of cigarette and e-cigarette use among dual users: A qualitative study. BMC Public Health, 15, 859. 10.1186/s12889-015-2198-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Pokhrel P, Schmid S, & Pagano I (2020). Physical activity and use of cigarettes and e-cigarettes among young adults. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 58(4), 580–583. 10.1016/j.amepre.2019.10.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potvin S, Tikàsz A, Dinh-Williams LL, Bourque J, & Mendrek A (2015). Cigarette cravings, impulsivity, and the brain. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 6, 125. 10.3389/fpsyt.2015.00125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Rainer MA, Xie B, Sabado-Liwag M, Kwan PP, Pike JR, Tan NS, Vaivao DES, Tui’one May V, Ka’ala Pang J, Pang VK, Toilolo TB, Tanjasiri SP, & Palmer PH (2019). Psychosocial characteristics of smoking patterns among young adult Samoans and Tongans in California. Addictive Behaviors Reports, 9, Article 100177. 10.1016/j.abrep.2019.100177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Subica AM, Guerrero E, Wu LT, Aitaoto N, Iwamoto D, & Moss HB (2020). Electronic cigarette use and associated risk factors in U.S.-dwelling Pacific Islander young adults. Substance Use & Misuse, 55(10), 1702–1708. 10.1080/10826084.2020.1756855 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United States Food and Drug Administration. (2020). Tips to Help Avoid “Vape” Battery Explosions. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. https://www.fda.gov/tobacco-products/products-ingredients-components/tips-help-avoid-vape-battery-explosions. [Google Scholar]

- *Wills TA, Bantum EO, Pokhrel P, Maddock JE, Ainette MG, Morehouse E, & Fenster B (2013). A dual-process model of early substance use: Tests in two diverse populations of adolescents. Health Psychology, 32(5), 533–542. 10.1037/a0027634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Wills TA, Knight R, Sargent JD, Gibbons FX, Pagano I, & Williams RJ (2017). Longitudinal study of e-cigarette use and onset of cigarette smoking among high school students in Hawaii. Tobacco Control, 26(1), 34–39. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2015-052705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Wills TA, Sargent JD, Knight R, Pagano I, & Gibbons FX (2016). E-cigarette use and willingness to smoke: A sample of adolescent non-smokers. Tobacco Control, 25(E1), 52. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2015-052349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Yang F, Cheng WJY, Ho M-HR, & Pooh K (2013). Psychosocial correlates of cigarette smoking among Asian American and Pacific Islander adolescents. Addictive Behaviors, 38(4), 1890–1893. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.12.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]