Abstract

Hydrogen bond engineering is widely exploited to impart stretchability, toughness, and self-healing capability to hydrogels. However, the enhancement effect of conventional hydrogen bonds is severely limited by their weak interaction strength. In nature, some organisms tolerate extreme conditions due to the strong hydrogen bond interactions induced by trehalose. Here, we report a trehalose network–repairing strategy achieved by the covalent-like hydrogen bonding interactions to improve the hydrogels’ mechanical properties while simultaneously enabling them to tolerate extreme environmental conditions and retain synthetic simplicity, which proves to be useful for various kinds of hydrogels. The mechanical properties of trehalose-modified hydrogels including strength, stretchability, and fracture toughness are substantially enhanced under a wide range of temperatures. After dehydration, the modified hydrogels maintain their hyperelasticity and functions, while the unmodified hydrogels collapse. This strategy provides a versatile methodology for synthesizing extremotolerant, highly stretchable, and tough hydrogels, which expand their potential applications to various conditions.

Trehalose network–repairing strategy is developed to greatly enhance the performances of hydrogels under various conditions.

INTRODUCTION

Hydrogels are biocompatible, mechanically tunable, conductive, and optically transparent, making them ideal materials for tissue engineering (1, 2), microlenses (3), ionic conductors (4), ionotronic devices (5), electroluminescent devices (6), soft robotic actuators (7–9), etc. These applications rely on the stable and excellent mechanical properties of hydrogels under various conditions such as dehydration and low temperatures. However, network imperfections in hydrogels have a considerable effect on their mechanical properties, which often lead to mechanical properties degradation. For example, the mechanical properties of hydrogels are far below their corresponding theoretical values under the perfect network assumption, which can vary by several orders of magnitude (10). Moreover, the material properties of hydrogels can be further exacerbated due to water crystallization at low temperatures and water loss caused by air drying since they become damaged, brittle, rigid, and nonconductive, which will result in malfunction of hydrogel devices such as contact lens (11) and microcarries (12) under these environmental stresses.

The significant gap between theory and experiment suggests a great potential to improve the mechanical properties of hydrogels by repairing network imperfections. Currently, intense efforts have been devoted to improving mechanical properties of hydrogels (13–17), while these strategies suffer from one or more limitations: complicated synthetic process, limited enhancement, lack of generality and biocompatibility, loss of functions after dehydration, and narrow working temperature range. It is very challenging to develop a general strategy to enhance the mechanical properties of hydrogels under various conditions while simultaneously retaining biocompatibility and synthetic simplicity. To this end, one needs to select an effective agent to fulfill the network-repairing function by introducing strong molecular interactions. Besides, a qualified agent should be biocompatible and ensure the sound operation of hydrogels under extreme conditions.

In nature, numerous organisms, including bacteria, fungi, yeast, plants, insects, and tardigrades, can survive against adverse environmental conditions such as low temperatures and dehydration (18–21). Especially, water bears can withstand extreme temperatures from −273° to 100°C, almost complete dehydration (22), and high pressure (23). Evidence shows that they adapt by synthesizing a large amount of trehalose when exposed to these environmental stresses (24). Specifically, trehalose molecules can stabilize biomolecules by forming the strong interactions between the ─OH groups in trehalose and polar groups in biomolecules, and they can even replace hydration water molecules with stronger hydrogen bonding to biomolecules (19, 25, 26). Besides, trehalose protects against water crystallization at low temperatures since it deconstructs the tetrahedral hydrogen bond network of water and inhibits the emergence of ice-forming hydrogen bond configurations (24, 26–29). It is well known that incorporating salts such as CaCl2 into hydrogels can improve their anti-freezing capabilities; however, this strategy can degrade their mechanical properties. For example, the mechanical properties of CaCl2-modified hydrogels, such as strength and stretchability, decrease obviously with the addition of CaCl2 at various temperatures (30). In addition, adding organic liquids such as propylene glycol into hydrogels can also improve their operating temperature range (31); however, the toxicity of organic liquids can result in health hazards and environmental pollution (32). In contrast, trehalose and its derivatives are environmentally benign and biocompatible. Inspired by its unique properties, trehalose can act as an effective network-repairing agent for hydrogels by introducing the covalent-like hydrogen bonding interactions, which is aimed to impart extra stretchability, high toughness, extremotolerant property, and self-healing capability to hydrogels.

RESULTS

Trehalose network–repairing strategy

Hydrogel network contains various imperfections; examples include dangling chains (e.g., chain ends or branched chains) and loop defects. After adding trehalose into polyacrylamide (PAAm) hydrogels, strong hydrogen bonds can be formed between trehalose molecules and many polar groups in the long polymer chains. As a result, there are many ways of interaction between trehalose and hydrogel network (Fig. 1A), for example, the dangling chains can be connected with the other dangling chains or the cross-linked polymer chains by trehalose at multiple interaction points, the cross-linked polymer chains can also interact with the other cross-linked polymer chains by trehalose, and so forth. All of these interaction ways can reinforce the hydrogel network. To quantitatively study the interaction strengths among water molecules (W), trehalose molecules (T), and PAAm molecules (P) in the hydrogel (Fig. 1B), Materials Studio is used to simulate the molecular structures and calculate the interaction energies based on density functional theory (DFT) (fig. S1 and Supplementary Text) (33–37). The interaction energy of T-W is smaller than those of W-W and P-W (table S1), suggesting that the stability of coexisted water and trehalose molecules is stronger than those of W-W and P-W. Besides, a smaller interaction energy of P-T compared with those of P-W and T-W indicates that stronger hydrogen bonds are formed between trehalose and PAAm molecular chains. Therefore, trehalose molecules are preferentially hydrogen-bonded to the polar groups of PAAm molecular chains. Hydrogen bond energies can span more than two orders of magnitude (from about −0.2 to −45.8 kcal/mol), and the nature of hydrogen bond within this range varies, i.e., its covalent, electrostatic, and dispersion contributions can change in their relative weights (38, 39). The hydrogen bond has a wide transition zone, which continuously merges with the covalent bond, van der Waals, and ionic interaction. On the basis of the DFT calculations (table S1), P-T generally has quadruple hydrogen bonds with interaction energy of −68.36 kcal/mol, and the averaged interaction energy (−17.09 kcal/mol) is within the range of hydrogen bond of strongly covalent nature (39).

Fig. 1. Trehalose network–repairing strategy achieved by the covalent-like hydrogen bonding interaction.

(A) Network-repairing strategy enabled by the covalent-like interactions between trehalose molecules and many polar groups in PAAm polymer chains, which can reinforce the hydrogel network. (B) Molecular models used to calculate the interaction energies among water, trehalose, and PAAm molecules. (C) FTIR spectra of 0, 10, 20, and 30 wt % trehalose–modified PAAm hydrogels. a.u., arbitrary units. (D) 1H-NMR spectra of 0, 10, 20, and 30 wt % trehalose–modified PAAm hydrogels.

Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) and proton nuclear magnetic resonance (1H-NMR) spectra are also used to characterize the hydrogen bonds induced by trehalose. PAAm hydrogel displays several characteristic peaks at 3478 and 3206 cm−1 for the stretching vibration of N─H and at 1705 cm−1 for the stretching of C═O. The formation of intermolecular hydrogen bonds between trehalose and PAAm chains is responsible for the shifts of the N─H and C═O peaks (Fig. 1C). We also characterized the hydrogen bonding interactions in the hydrogel in its original hydrated state by using the attenuated total reflectance FTIR spectroscopy because the hydrogel subjected to freeze-drying and grinding will not be 100% the same as its original hydrated state. The peak at 1654 cm−1 of the as-prepared PAAm hydrogel, which is attributed to the stretching of C═O, shifts to 1624 cm−1 in the 30 weight % (wt %) trehalose–modified PAAm hydrogel. Peaks at 3225 and 3369 cm−1 representing the stretching vibration of N─H shift to 3183 and 3322 cm−1 in the 30 wt % trehalose–modified PAAm hydrogels (fig. S2). FTIR spectra of hydrogels in the original hydrated state are similar to that in the dried state, both of which suggest the formation of intermolecular hydrogen bonds between trehalose and PAAm chains.

The covalent-like hydrogen bonds between trehalose and PAAm polymer chains have been further confirmed by 1H-NMR. The peaks at about 5.57 and 6.15 parts per million (ppm) can be attributed to H in ═CH2 groups (H1, H2), the peak at about 6.06 ppm is attributed to ═CH─ groups (H3), and the peaks at about 7.04 and 7.48 ppm represent H in ─NH2 groups (H4 and H5) of PAAm (Fig. 1D). In the trehalose-modified PAAm hydrogels, the peaks in the range of 4.31 to 4.86 ppm are attributed to the ─OH groups in trehalose. Besides, the characteristic peaks of PAAm become much smoother than that of the pure PAAm hydrogel (fig. S3), indicating the formation of the covalent-like hydrogen bonds between trehalose molecule and PAAm chains.

Enhancement effect

We synthesized a series of hydrogels by adding 0, 10, 20, and 30 wt % trehalose to the PAAm hydrogels and characterized the mechanical properties of these hydrogels by measuring the stress-stretch curves of notched and intact samples (Materials and Methods). Figure 2A shows the stress-stretch curves of 0, 10, 20, and 30 wt % trehalose–modified hydrogels, respectively, at room temperature. The strength and stretchability of hydrogels measured by the pure shear tests increase from 19 kPa and 1150% to 81 kPa and 4100%, respectively, as the trehalose content increases from 0 to 30 wt %. The enhancement effect of trehalose is also very pronounced for PAAm hydrogels soaked in trehalose solutions. To test the mechanical properties of soaked hydrogels, we first synthesized four identical PAAm hydrogels based on the preparation method. Then, the three PAAm hydrogels are soaked in solutions with 10, 20, and 30 wt % concentrations of trehalose, respectively. After reaching the final equilibrium states, the soaked hydrogels were taken out for mechanical characterization, the mechanical test of pure PAAm hydrogel was also performed, and the stress-stretch curves of all hydrogels were obtained (fig. S4). Compared with the pure PAAm hydrogel, the strength and stretchability of hydrogels soaked in solutions with different trehalose concentrations are significantly enhanced, increasing from 40 kPa and 1330% to 365 kPa and 2520%, respectively, as the trehalose content increases. As shown in Fig. 2A, the initial shear modulus, which can be approximately evaluated as one-fourth of the initial slope of stress-stretch curves under the pure shear test (40), decreases with the increasing trehalose content. In contrast with the slightly decreased initial shear modulus of modified PAAm hydrogels synthesized in situ, the initial shear modulus of soaked PAAm hydrogels increases with increasing trehalose content (fig. S4).

Fig. 2. Enhancement effect of trehalose network–repairing strategy on the mechanical properties of PAAm hydrogels at room temperature.

(A) Stress-stretch curves of 0, 10, 20, and 30 wt % trehalose–modified hydrogels at 25°C measured by the pure shear tests. (B) Stress-stretch curves of precut hydrogels with different trehalose contents measured by the pure shear tests. (C) Fracture toughness and maximum elongation of the modified hydrogels increase greatly with increasing trehalose content. (D) Toughening mechanisms of the trehalose-modified hydrogels; the size of the failure process zone around the crack tip becomes larger. (E) Fractocohesive lengths of PAAm hydrogels increase with increasing trehalose content. (F) A mechanical properties space for soft materials; the two axes represent the fracture energy Г and the work to rupture W*, respectively, and the dashed line represents the fractocohesive length Г/W*. The trehalose-modified PAAm hydrogels are compared with PAAm hydrogels, DN hydrogels (2), alginate hydrogels (55), PVA hydrogels (56), skin (57), natural rubbers (58), and polyurethane (46). (G) Trehalose-modified hydrogels with the edge cut are highly stretchable and exhibit flaw-tolerant capability. Photo credit: Zilong Han, Zhejiang University.

The initial shear modulus can be estimated by (10, 40, 41). ϕp is the volume fraction of polymer in the hydrogel, N is the number of polymer chains per unit volume of the dry polymer, and kT can be taken as 4.1 × 10–21 J at room temperature. On the basis of the preparation method (Materials and Methods), the mass and volume fraction of water, trehalose, and PAAm can be calculated. The mass fraction of water in all hydrogels decreases with the increasing trehalose content, while the volume fraction of polymer ϕp in all hydrogels remains nearly the same (about 0.11). It is revealed that simple sugar molecules such as trehalose can block polymer formation (42, 43). Specifically, trehalose binds to the exposed groups on polymer, which can affect the transition step from native to polymer state, thus making the polymer less polymerogenic. As for the polymerization process of PAAm hydrogel, high concentrations of trehalose can bind to many exposed polar groups on polymer chains and monomers through the extra strong hydrogen bonds, thus making PAAm less polymerogenic. Therefore, high concentrations of trehalose affect the polymerization process of PAAm, which can directly decrease the number of chains per unit volume N. The estimated number of chains per unit volume is within the range of 0.69 × 1024 to 2.07 × 1024 m−3, which is consistent with the predicted results (40). In addition, the strong hydrogen bonding interactions between trehalose and polymer chains might decrease the intrachain van der Waals interactions because the spacing of polar groups in the polymer chains is altered (19). Therefore, compared with the pure PAAm hydrogel, the synergistic effect of these mechanisms results in the decreased initial shear modulus of modified hydrogels. In contrast, the number of chains per unit volume N is the same for all PAAm hydrogels since they are synthesized by the same preparation method. After soaking in the trehalose solution, the effective number of chains per unit volume increases because trehalose molecules strongly interact with the hydrogel polymer network (Fig. 1A). As a result, the initial shear modulus of soaked hydrogel increases as the trehalose content increases. Cross-linked polymer chains generally exist in the form of random coils; the initial effect of applied loading is to stretch these coil segments, followed by chain scission and chain pullout. Upon further stretching, chain scission occurs in effective polymer chains, causing failure of the trehalose-free hydrogel. However, trehalose can repair the hydrogel network dynamically by the covalent-like hydrogen bonding interactions, which accounts for the high stretchability of modified hydrogels. Besides, more hydrogen bonds are introduced at multiple link sites, which is responsible for the improved strength of trehalose-modified hydrogels. Such simultaneous enhancement in several mechanical properties without sacrificing specific property is very pronounced for the original weak PAAm hydrogel (10).

Following the Rivlin-Thomas method (44, 45), we also measured the fracture toughness of all hydrogels by performing the pure shear tests (Materials and Methods). Specifically, we used another sample with the same dimension and the edge cut of length 5 mm is introduced into the sample (Fig. 2B and movies S1 to S4). The fracture toughnesses of 0, 10, 20, and 30 wt % trehalose–modified PAAm hydrogels are evaluated as 474, 1163, 2039, and 5116 J/m2, respectively. It is obvious that the fracture toughness increases greatly with increasing trehalose content (Fig. 2C). Fracture toughness is the energy dissipated in advancing a unit area of the crack. The Irwin-Orowan model indicates that the fracture process of hydrogel includes the rupture of a layer of chains on the crack plane and some polymer chains off the crack plane (10). Therefore, the fracture toughness Γ of hydrogel is the sum of the intrinsic fracture energy Γ0 and the mechanical dissipation in the process zone around the crack tip ΓD (45). Γ0 represents the energy required to fracture a layer of chains on the crack plane. As for the trehalose-modified PAAm hydrogels, both Γ0 and ΓD are enhanced by the covalent-like hydrogen bonding interaction. Compared with the unmodified PAAm hydrogel, more energy is required to fracture a layer of polymer chains per unit crack area since the extra “polymer chains” are formed across the crack plane by the strong hydrogen bonds between trehalose and polymer chains; the mechanical dissipation ΓD in the dissipation zone around the crack tip is also significantly increased since the mechanically dissipated energy per unit volume of the process zone and the size of the process zone become much larger (Fig. 2D). As the mechanical work is imported to the trehalose-modified hydrogel, energy dissipates to break not only the original polymer chains but also the extra polymer chains on and off the crack plane. The covalent-like hydrogen bonding interactions enable extra energy dissipation, which is responsible for the greatly improved fracture toughness of trehalose-modified hydrogels.

Noticing that the trehalose-modified PAAm hydrogels with the precut are still highly stretchable, we analyzed the flaw sensitivity of modified PAAm hydrogels. For this purpose, we performed the mechanical tests on the modified hydrogels with the edge cut of different lengths such as 10 and 15 mm. The stretchability of trehalose-free PAAm hydrogels is sensitive to flaws. By contrast, the trehalose-modified PAAm hydrogels with large cut are still highly stretchable, which exhibit the flaw-tolerant capability (fig. S5 and Supplementary Text), i.e., the stretchability and strength are insensitive to small cuts in the sample but drop significantly when the cuts become very large. The transition occurs when the cut length of sample is larger than its fractocohesive length (46), which is defined as the ratio of fracture energy to work to rupture, namely, ξ ~Γ/W∗. When the flaw size is small compared to ξ, the stretchability is insensitive to the flaw; when the flaw size is large compared to ξ, the stretchability decreases significantly as the flaw size increases. The fractocohesive lengths of 0, 10, 20, and 30 wt % trehalose–modified PAAm hydrogels are calculated as 3.02, 11.35, 16.56, and 19.48 mm, respectively (Fig. 2E). It is obvious that trehalose significantly increases the flaw-tolerant capability of hydrogels. As for the trehalose-modified hydrogels, their fracture energy is significantly enhanced from 474 to 5116 J/m2, which tends to increase the fractocohesive length of the hydrogel. In general, improving the fracture energy of hydrogel makes them more flaw tolerant (45). Physically, the fractocohesive length describes the size of failure zone around the crack tip where the mechanical dissipation sets in (47). Figure 2D shows that the size of failure process zone around the crack tip becomes larger due to the covalent-like hydrogen bonding interactions, which is manifested as large mechanical dissipation. As expressed in the space of Г and W* (Fig. 2F), the trehalose-modified PAAm hydrogels show excellent flaw-tolerant ability, which is essential for wearable hydrogel electronics, hydrogel origami and kirigami structures, wound dressings, and soft devices. Specifically, the cut in trehalose-free hydrogels runs rapidly through the entire sample when stretched to about nine times its original height (Fig. 2G). By contrast, the trehalose-modified hydrogels with the cut are highly stretchable, which can even be stretched to about 41 times.

Tolerating low temperatures

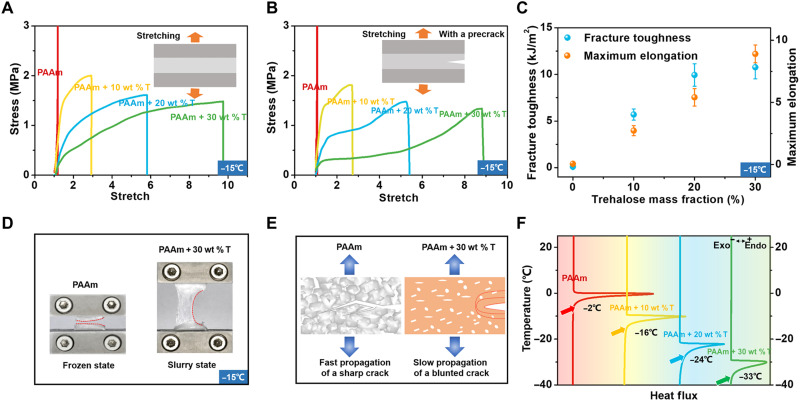

Since trehalose can endow hydrogels with anti-freezing capability, we further explored the mechanical behaviors of trehalose-modified PAAm hydrogels at low temperatures. For this purpose, the mechanical responses of PAAm hydrogels with 0, 10, 20, and 30 wt % trehalose are measured at −15°C. The stress-stretch curves of intact and notched samples are shown in Fig. 3 (A and B, respectively). The trehalose-free PAAm hydrogel is fully frozen and becomes stiff and brittle, while the trehalose-modified hydrogels retain their high stretchability and flexibility (fig. S6). Compared with the mechanical properties of hydrogels at room temperature, the elastic moduli and strengths of all hydrogels increase, while their stretchability decreases, which are attributed to the gradually increasing volume fraction of ice crystals.

Fig. 3. Trehalose-modified PAAm hydrogels maintain their hyperelasticity and flexibility at low temperatures.

(A) Tensile stress-stretch curves of 0, 10, 20, and 30 wt % trehalose–modified hydrogels at −15°C. (B) Tensile stress-stretch curves of precut hydrogels with different trehalose contents. (C) Fracture toughness and maximum elongation of the modified PAAm hydrogels increases with increasing trehalose content. (D) Failure scenarios of 0 and 30 wt % trehalose–modified hydrogels at low temperatures. (E) Toughening mechanisms of the modified hydrogels at low temperatures. (F) Experimental DSC results for all hydrogels.

The fracture toughness of modified hydrogels is measured at −15°C by using the pure shear tests, which is a function of trehalose content. As shown in Fig. 3C, fracture toughness greatly increases with increasing trehalose content at −15°C. For the 0 wt % trehalose hydrogel, fracture toughness at −15°C is smaller than that at 25°C, which is consistent with the results (30). The 0 wt % trehalose hydrogel almost completely freezes at −15°C, and it fails by a sharp crack rapidly propagating through the sample (Fig. 3D), resulting in relatively low fracture toughness. By contrast, the fracture toughnesses of hydrogels with 10, 20, and 30 wt % trehalose at −15°C shoot up several times compared to their corresponding values at 25°C. Trehalose can deconstruct the hydrogen bond network of water, thus inhibiting the formation of ice crystals in hydrogels at low temperatures (26). Therefore, the modified hydrogels maintain a partially frozen state over a wide temperature range, i.e., small ice crystals are randomly distributed in hydrogels (fig. S7). The failure scenarios show that a large blunted crack appears to stagnate at the crack front as the tension increases (Fig. 3, D and E). Complicated crack paths (e.g., zigzag and discontinuous) due to crack pinning and deflection were observed in the trehalose-modified hydrogels, and the final crack surfaces are rough, which accounts for the enhanced toughness at low temperatures.

The states of water in hydrogel can be classified as nonfreezing and strongly bound water (non–freezing bound water), freezing and weakly bound water (freezing bound water), and non–bound free water (free water), which will freeze below 0°C (48). The fraction of different states of water in hydrogel depends on the trehalose content. As a result, the state of hydrogels can be largely affected by the trehalose content at low temperatures. To measure the transition temperature from slurry state to frozen state, we characterized the PAAm hydrogels with various compositions by using dynamic scanning calorimetry (DSC) (Materials and Methods). Depending on the trehalose content, the hydrogels freeze over a range of temperatures from 0° to −33°C. The transition temperature decreases as the trehalose content increases (Fig. 3F).

Tolerating dehydration

Water loss in hydrogels generally results in severe degradation of material properties (49, 50). However, trehalose can effectively slow down the water loss process of hydrogels and confers protection to the hydrogel network during and after dehydration (fig. S8 and Supplementary Text). Correspondingly, the mechanical properties of trehalose-modified hydrogels are maintained, while the unmodified hydrogels suffer severe degradation of mechanical properties, thus losing their desired functions. After 72 hours of freeze-drying at −80°C, the volume and weight of all hydrogel samples were reduced due to water loss (figs. S9 and S10). The 0 wt % trehalose hydrogel collapse and becomes stiff and brittle, losing its flexibility and functions. By contrast, the 30 wt % trehalose hydrogel maintains its hyperelasticity and flexibility (Fig. 4, A and B), which can be stretched, folded, and twisted (movies S5 to S7). The water-retaining capability of trehalose-modified hydrogels is further investigated. We compared trehalose with the traditional water retention agents such as LiCl and CaCl2 (50). We prepared the modified PAAm hydrogels with the same molar concentration (0.53 M) of LiCl, CaCl2, and trehalose and measured the change in mass of these hydrogels subjected to 168 hours of freeze-drying at −80°C (figs. S11 and S12). After 168 hours of freeze-drying, the unmodified hydrogel lost 96.8% of the initial mass of water in the hydrogel, the CaCl2-modified hydrogel lost 90.3% of the initial mass of water in the hydrogel, the LiCl-modified hydrogel lost 90.0% of the initial mass of water in the hydrogel, and the mass of trehalose-modified hydrogel lost 81.4% of the initial mass of water in the hydrogel. Therefore, trehalose-modified hydrogels have the most excellent water retention capacity, which benefits from the extra strong hydrogen bonding interactions.

Fig. 4. Trehalose-modified PAAm hydrogels maintain their mechanical properties after dehydration.

(A) Tensile tests of 0 and 30 wt % trehalose–modified hydrogels subjected to 72 hours of freeze-drying at −80°C; the modified hydrogels maintain their hyperelasticity, while the unmodified hydrogels become stiff and brittle. (B) Stress-stretch curves of 0 and 30 wt % trehalose–modified hydrogels subjected to 72 hours of freeze-drying at −80°C. (C) Cross-sectional SEM images of the 0, 10, 20, and 30 wt % trehalose–modified hydrogels after freeze-drying viewed at different magnifications; trehalose clusters are distributed randomly throughout the modified hydrogel network.

To investigate the protective mechanisms induced by trehalose, we analyzed the microstructures and chemical compositions of all hydrogels by performing scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and energy-dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) characterization. Figure 4C shows the SEM images of all hydrogels under different magnifications, in which the polymer network of the 0 wt % trehalose–modified PAAm hydrogel collapses due to the lack of water support. As for the trehalose-modified PAAm hydrogels, molecular clusters displayed as circular or elliptical shapes are distributed randomly throughout the hydrogel network as shown in the cross-section SEM images. To identify the chemical compositions of these clusters, EDS spectra of the specified region of 30 wt % trehalose–modified PAAm hydrogel were characterized. The EDS spectrum of the cluster position shows the characteristic peak of carbon and oxygen element but does not show the characteristic peak of nitrogen element (fig. S13), suggesting that the cluster regions are not pores and polymer chains. Besides, as shown in Fig. 4C, the SEM image of 30 wt % trehalose–modified PAAm hydrogel shows circular or elliptical clusters, which is in stark contrast with the pores with irregular shapes in the SEM image of pure PAAm hydrogel. Furthermore, trehalose molecules can bind with each other through hydrogen bonds to form clusters of various sizes (51). The EDS spectrum of polymer network position shows the peak of nitrogen element (fig. S13) because only the PAAm polymer chain contains the nitrogen element. Therefore, by characterizing the distribution of nitrogen, carbon, and oxygen element, the smooth circular or elliptical regions of trehalose-modified PAAm hydrogel are trehalose clusters.

The presence of trehalose clusters can provide effective support for the network of hydrogels after dehydration. When subjected to 72 hours of freeze-drying at −80°C, the trehalose-modified PAAm hydrogel is still in the partially hydrated state; trehalose can effectively slow down the water loss process of hydrogels since the strong hydrogen bonding interactions are formed between water molecule, trehalose molecule, and PAAm chains (table S1). Besides, trehalose molecules can replace water molecules bonded to the polymer chains since stronger hydrogen bonds are formed between trehalose and polymer chains. The protective effect of trehalose on the hydrogel network during and after dehydration is mainly attributed to the support of trehalose clusters and the water-retaining mechanism.

General applicability

The trehalose network–repairing strategy is proved to be useful for enhancing various kinds of hydrogels. The widely used hydrogels, including PAAm-alginate double-network (DN) hydrogel, polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) hydrogel, and tetra-arm polyethylene glycol (PEG) hydrogel, are chosen as model materials (Supplementary Text). We synthesized the trehalose-modified PAAm-alginate DN and PVA hydrogels and measured their stress-stretch curves (Materials and Methods). Compared with the unmodified DN hydrogels, the stretchability and strength of modified DN hydrogels are improved (Fig. 5, A and B). The enhancement effect by trehalose is more pronounced for PVA hydrogels; the strength and stretchability of modified hydrogels are significantly enhanced (Fig. 5, C and D), which is attributed to the strong interaction between trehalose and polymer chains promoting the formation of physical cross-linking points (fig. S14 and Supplementary Text). As for the modified DN hydrogels synthesized in situ with trehalose, their average initial modulus slightly decreases with the increasing trehalose content (Fig. 5B), which is consistent with the modified PAAm hydrogel formed in situ with trehalose. The PAAm hydrogels and the DN hydrogels are formed by covalent cross-linking, while the PVA hydrogels prepared by the repeated freezing and thawing method are the physically cross-linked hydrogels. More physical cross-linkers are introduced into the PVA hydrogels induced by trehalose, which is responsible for the increased initial shear modulus.

Fig. 5. General applicability of trehalose network–repairing strategy.

(A) Enhancement effect of trehalose on PAAm-alginate DN hydrogels. (B) Fracture stress and Young’s modulus of the DN hydrogels as a function of trehalose content. (C) Enhancement effect of trehalose on PVA hydrogels. (D) Fracture stress and Young’s modulus of the PVA hydrogels as a function of trehalose content.

We also synthesized the tetra-arm PEG hydrogels (52) with ideal network or controlled densities of network imperfections by using the method (53). Since the N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS) group can become inactive by hydrolyzing the activated esters, defects such as dangling chains can be introduced into hydrogels by controlling the degradation time of PEG-NHS. The stress-stretch curves of the tetra-arm PEG hydrogel with ideal networks (P) and controlled defects (D) are measured. The strength decreases, and the critical stretch increases due to the introduced network imperfections, i.e., dangling chains (fig. S15). Then, both the ideal and defective PEG hydrogels are soaked in solutions with 10 wt % concentrations of trehalose. After reaching the equilibrium states, the trehalose-modified PEG hydrogels were taken out for mechanical characterization, and the stress-stretch curves are also shown in fig. S15. For the ideal PEG hydrogel, its strength and stretch increase slightly with the addition of trehalose because the cross-linked polymer chains can interact with the other cross-linked polymer chains by trehalose (Fig. 1A). Similarly, for the defective PEG hydrogel, its strength and stretch increase significantly with the addition of trehalose because polymer chains, including the dangling chains, interact strongly with the remaining polymer chains, such as dangling chains and cross-linked polymer chains (Fig. 1A).

Trehalose endows hydrogels with self-healing capability due to the abundant covalent-like hydrogen bonds between trehalose and PAAm chains (fig. S16). Furthermore, the network-repairing strategy can be easily achieved by soaking the hydrogel samples into the trehalose solution, which will simultaneously enhance their mechanical properties such as strength, stretchability, initial shear modulus, and fracture energy. Inspired by the unique properties of trehalose, the network-repairing strategy might be extended to other types of saccharides. For this purpose, we also synthesized the PAAm hydrogels modified by other types of saccharides such as sucrose, lactose, and glucose and then measured their mechanical responses at room temperature (fig. S17). The mechanical properties of all modified hydrogels, including strength and stretchability, are enhanced in varying degrees. Among all the tested saccharide-modified hydrogels, the enhancement effect by trehalose on the hydrogels’ mechanical properties is the most pronounced.

Applications

The integrated properties of modified hydrogels expand their potential applications under various conditions. During the preparation process of PAAm hydrogel, ammonium persulfate is added as the initiator, and the free ions such as NH4+, S2O82−, HSO4−, H+, and SO42− are introduced into the hydrogels. As a result, the PAAm hydrogel shows a conductivity of about 0.32 S/m, which will become nonconductive at low temperatures. However, the trehalose-modified hydrogels can maintain their conductivity at low temperatures since they are partially frozen (Fig. 6A). The conductivity of all hydrogels was measured at 25°, −5°, and −15°C. The 0 wt % trehalose hydrogel completely freezes at low temperatures, and its conductivity decreases from 0.32 S/m at 25°C to about 0 S/m at −15°C. Thus, the modified hydrogels illuminate the light-emitting diode (LED) lamp at −5°C, whereas the 0 wt % trehalose hydrogel does not (fig. S18). Conductivity degradation can be alleviated by the addition of trehalose. Specifically, the difference in conductivities between 25° and −15°C would decrease as the mass fraction of trehalose increases, and the situation is similar for the difference in conductivities between 25° and −5°C.

Fig. 6. Applications are enabled by the stretchable, tough, anti-freezing, and anti-drying hydrogels.

(A) Trehalose mitigates conductivity reduction of hydrogels caused by decreasing temperature (conductivity difference between 25° and −5° or 25° and −15°C). (B) Relative resistance ratio of the trehalose-modified hydrogels at −5°C when subjected to press loading. (C) Stretch loading. (D) Stress-strain curves, residual strain, and recovery ratio of the trehalose-modified hydrogels vary with loading/unloading cycles at −5°C.

We also demonstrated a simple pressure/strain sensor working at low temperatures that requires both good conductivity and excellent mechanical properties of hydrogels. The mechanical loadings are applied to the hydrogels in the electric circuit. The relative resistance variation (R − R0)/R0 was measured, where R0 and R are the initial resistance and the real-time resistance. Figure 6 (B and C) illustrates the responses of the sensors operating at −5°C subjected to pressing and stretching, respectively. The relative resistance variation increases to different levels as the mechanical loading is applied, and it will return to the initial value after releasing the loading. The current-time curves with a high signal-to-noise ratio were recorded under each mechanical stimulus. Furthermore, when subjected to cyclic loading, the sensors display excellent stability and reversibility characterized by stable relative resistance variation, small residual strain, and large recovery ratio (Fig. 6D and fig. S19).

DISCUSSION

We report a versatile strategy to enhance the mechanical properties of various hydrogels including PAAm, PVA, and PAAm-alginate DN hydrogels while simultaneously enabling them to tolerate adverse environmental conditions and to retain synthetic simplicity. Trehalose acts as the network-repairing agent by forming the covalent-like hydrogen bonds between trehalose and polymer chains. As a result, the strength, stretchability, and fracture toughness of the modified hydrogels significantly increase with increasing trehalose content. Since trehalose inhibits the formation of ice crystals by deconstructing the ice-forming hydrogen bond configurations, the modified hydrogels can retain their high stretchability, fracture toughness, and conductivity at low temperatures. Furthermore, trehalose protects the molecular structure of hydrogels after dehydration and consequently maintains their mechanical properties and functions. The protective roles are attributed to the support of trehalose clusters and the water-retaining mechanism. Last, we demonstrated several applications that require both good conductivity and excellent mechanical properties of hydrogels. This strategy provides a versatile methodology for greatly improving the mechanical properties of hydrogels under various conditions, which will expand the scope of hydrogel applications.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

AAm 99% (lot number A108465), trehalose (lot number D110019), PVA with a hydrolysis degree of 99% (lot number P105126), sodium alginate (S100128), and calcium sulfate dihydrate (CaSO4∙2H2O; lot number C101878) were purchased from Aladdin, Shanghai, China. N,N′-methylenebisacrylamide 98% (MBAA; lot number 146072) and ammonium persulfate 98% (lot number 248614) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. The tetra-amine–terminated PEG macromers (PEG-NH2) and tetra-NHS–terminated PEG macromers (PEG-NHS) were purchased from SINOPEG, Xiamen. All chemicals were used as received.

Preparation of the trehalose-modified PAAm hydrogels

Trehalose (0, 2, 4, and 6 g) was dissolved in distilled water to form the sugar solutions with mass fractions of 0, 10, 20, and 30%, respectively. For every 1 ml of each solution, 0.14 g of AAm was added as hydrogel monomers, 4 μl of MBAA (0.1 M) was added as the cross-linker, and 20 μl of ammonium persulfate (0.1 M) was added as the initiator. Then, the solutions were completely stirred, degassed, poured into acrylic molds, and covered with transparent acrylic sheets. The covered molds were then placed under ultraviolet lamps. The mixed solutions were exposed to ultraviolet irradiation for 60 min to complete polymerization (fig. S20). Afterward, samples were taken out from the molds and used for testing.

Preparation of the trehalose-modified DN hydrogels

We prepared PAAm-alginate DN hydrogels by following the method (2). AAm (13.5 g), alginate (3.25 g), and trehalose powder (0, 2.5, 5, and 10 g) were dissolved in 100 ml of distilled water to form aqueous solutions. After 6 hours of stirring, 0.0081 g of MBAA, 0.0336 g of tetramethylethylenediamine, 0.135 g of ammonium persulfate, and 0.297 g of CaSO4∙2H2O were added to the aqueous solutions. Then, the solutions were degassed, poured into acrylic molds, and kept at room temperature for 24 hours to allow complete polymerization.

Preparation of the trehalose-modified PVA hydrogels

Trehalose-repaired PVA hydrogels were prepared by the freeze-thaw process (54). An aqueous solution containing 12 wt % PVA was prepared by heating at 80°C. Trehalose (0, 1, 3, and 5 wt %) was added to the PVA solution, respectively. The solutions were sonicated and vortexed for 1 hour to remove the air bubble and to ensure that the polymer solutions were thoroughly mixed. The solutions were then poured into acrylic molds followed by freezing at −20°C for 18 hours and cooling at room temperature (30 min) for three continuous cycles.

Preparation of the trehalose-modified tetra-arm PEG hydrogels

By using the method (53), the tetra-arm PEG hydrogels were synthesized on the basis of PEG-NH2 and PEG-NHS. Specifically, we dissolve and vigorously mix 0.8 g of PEG-NH2 in 8 ml of phosphate buffer solution, which has a pH of 7.4 and an ionic strength of 0.1 M. Then, we dissolve and vigorously mix 0.8 g of PEG-NHS in 8 ml of phosphate-citric acid buffer solution, which has a pH of 5.8 and an ionic strength of 0.1 M. The tetra-arm PEG hydrogels with controlled defects are obtained with the degraded time of 1 hour. Thereafter, we vigorously mix the solutions of PEG-NH2 and PEG-NHS and poured the mixed solution into a rectangular-shaped mold (50 mm × 30 mm × 2 mm). Subsequently, the samples are placed in a humidity chamber for at least 24 hours. Last, both the ideal and defective PEG hydrogels are soaked in solutions with 10 wt % concentrations of trehalose.

FTIR characterization

Infrared spectra of the trehalose-modified hydrogels in the dried state were measured by using FTIR spectroscopy (Nicolet iS10 FTIR; Thermo Fisher Scientific). Hydrogel samples were lyophilized and grinded in liquid nitrogen. The dried sample powder was blended homogeneously with KBr pellet and scanned against a blank KBr pellet background. All the spectra were obtained at room temperature with 32 scans and a resolution of 4 cm−1 in the range of 400 to 4000 cm−1.

Infrared spectra of the trehalose-modified hydrogels in the original hydrated state were measured by using attenuated total reflectance FTIR spectroscopy (Nicolet iS10 ATR-FTIR, Thermo Fisher Scientific). All the spectra were also obtained at room temperature with 32 scans and a resolution of 4 cm−1 in the range of 400 to 4000 cm−1.

1H-NMR characterization

The trehalose-modified hydrogels were characterized by 1H-NMR (400 MHz Bruker Avance II NMR spectrometer, Bruker BioSpin Co., Switzerland) with deuterated dimethyl sulfoxide as the solvent. NMR peak of the solvent (δ = 2.50 ppm) was used as the reference.

Mechanical characterization

At least four specimens were used for all test conditions. The nominal stress-stretch curves were measured by using the hydrogel specimens with the width of 25 mm (L), the height of 5 mm, and the thickness of 2 mm at room temperature (25°C). Tensile tests were performed to fracture by the test machine (Instron 5944) at a strain rate of 0.2 s−1. The nominal stress was evaluated by dividing the applied load by the initial cross-sectional area of the sample (the product of width and thickness), and the stretch was computed by dividing the deformed length by the initial length. In addition, a humidifier is used to prevent water loss.

We measured the fracture toughness of hydrogels using the pure shear test; a razor blade was used to create a notch of 5 mm starting from the edge of the identical specimens (25 mm in width, 5 mm in height, and 2 mm in thickness). Then, we measured the stress-stretch curves of specimens with the notch, and the critical stretch for fast fracture of the notched specimen was determined. By using the method proposed by Rivlin and Thomas (44), the critical energy release rate was determined

Γ = W(λc)H

where H is the initial height of the specimen and W(λc) is the area below the nominal stress-stretch curve of the unnotched specimen integrated up to the critical stretch λc of the notched specimen. For all tests, a humidifier was used to prevent the hydrogel from losing water.

At low temperatures (−15°C), hydrogel samples with a rectangular shape (10 mm in width, 2 mm in height, and 1 mm in thickness) were fixed to two rigid acrylic grips and mounted in the dynamic mechanical analysis (RSA-G2). Liquid nitrogen was used to control the environmental temperature. Tensile tests of all hydrogels were performed at a strain rate of 0.2 s−1 and recorded with a digital camera (Nikon D7200).

Thermal characterization

Differential scanning calorimeter (TA Instruments, DSC Q20) was used to characterize the samples. Samples were placed in hermetically sealed aluminum crucibles during the test, and a reference crucible was also contained. The nitrogen flow rate was 50 μl min−1. The sample was initially equilibrated at temperature of 40°C and then cooled to −90°C at the rate of −5°C min−1. After an isothermal period of at least 90 min, samples were heated up to 40°C at the rate of 5°C min−1.

Microstructure characterization

The PAAm hydrogels and the trehalose-modified PAAm hydrogels were subjected to freeze-drying treatment. Then, their microstructure was characterized by a SEM (Phenom-World, Holland) at an acceleration voltage of 10 kV. To identify the chemical compositions of the specified regions of hydrogels, EDS characterization of the specified regions of 30 wt % trehalose–modified PAAm hydrogel was performed using a HITACHI SU-7 instrument (Tokyo, Japan) operated at an accelerating voltage of 20 kV.

Electrical properties characterization

The samples were prepared and cut into a rectangular shape with a dimension of 20 mm × 10 mm × 2 mm. The sample’s resistance (R) in the static state was measured with a multimeter (Keithley, DAQ6510), and the conductivity σ was calculated on the basis of the following equation

σ = L/(A × R)

where L and A are the thickness and area, respectively. The measurement was performed for each hydrogel composition at room temperature and low temperatures (−5° and −15°C), respectively.

To measure the relative resistance variations of the hydrogels at −5°C, two-sided copper tapes were used to connect the sample ends to the probes. Then, the sample’s electrical resistance was tested and recorded with a two-probe digital multimeter (Keysight Co. Ltd., 34465a) when the sample was subjected to the repeated mechanical loading and unloading (press loading and stretch loading).

Acknowledgments

We thank K. Sharma and B. Yiming for their help in the experiments and/or discussions.

Funding: This work is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (nos. 91748209, 11525210, and 12132014), the 111 Project (no. B21034), Key Research and Development Program of Zhejiang Province (2020C05010), and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (no. 2020XZZX005-02).

Author contributions: S.Q., P.W., and W.Y. guided the entire work. Z.H., P.W., and S.Q. conceived the concept. Z.H., P.W., and Y.L. designed and performed the experiments and processed the data. P.W. drafted the manuscript. All authors contributed to the writing of the manuscript.

Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Data and materials availability: All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials.

Supplementary Materials

This PDF file includes:

Supplementary Text

Figs. S1 to S20

Table S1

Other Supplementary Material for this manuscript includes the following:

Movies S1 to S7

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Hua M., Wu S., Ma Y., Zhao Y., Chen Z., Frenkel I., Strzalka J., Zhou H., Zhu X., He X., Strong tough hydrogels via the synergy of freeze-casting and salting out. Nature 590, 594–599 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sun J. Y., Zhao X., Illeperuma W. R. K., Chaudhuri O., Oh K. H., Mooney D. J., Vlassak J. J., Suo Z., Highly stretchable and tough hydrogels. Nature 489, 133–136 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dong L., Agarwal A. K., Beebe D. J., Jiang H., Adaptive liquid microlenses activated by stimuli-responsive hydrogels. Nature 442, 551–554 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Keplinger C., Sun J.-Y., Foo C. C., Rothemund P., Whitesides G. M., Suo Z., Stretchable, transparent, ionic conductors. Science 341, 984–987 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yang C., Suo Z., Hydrogel ionotronics. Nat. Rev. Mater. 3, 125–142 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Larson C., Peele B., Li S., Robinson S., Totaro M., Beccai L., Mazzolai B., Shepherd R., Highly stretchable electroluminescent skin for optical signaling and tactile sensing. Science 351, 1071–1074 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wehner M., Truby R. L., Fitzgerald D. J., Mosadegh B., Whitesides G. M., Lewis J. A., Wood R. J., An integrated design and fabrication strategy for entirely soft, autonomous robots. Nature 536, 451–455 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cangialosi A., Yoon C., Liu J., Huang Q., Guo J., Nguyen T. D., Gracias D. H., Schulman R., DNA sequence–directed shape change of photopatterned hydrogels via high-degree swelling. Science 357, 1126–1130 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Han Z., Wang P., Mao G., Yin T., Zhong D., Yiming B., Hu X., Jia Z., Nian G., Qu S., Yang W., Dual pH-responsive hydrogel actuator for lipophilic drug delivery. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 12, 12010–12017 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yang C., Yin T., Suo Z., Polyacrylamide hydrogels. I. Network imperfection. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 131, 43–55 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maldonado-Codina C., Efron N., Impact of manufacturing technology and material composition on the mechanical properties of hydrogel contact lenses. Ophthalmic Physiol. Opt. 24, 551–561 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hernández R. M., Orive G., Murua A., Pedraz J. L., Microcapsules and microcarriers for in situ cell delivery. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 62, 711–730 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gong J. P., Katsuyama Y., Kurokawa T., Osada Y., Double-network hydrogels with extremely high mechanical strength. Adv. Mater. 15, 1155–1158 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang Q., Mynar J. L., Yoshida M., Lee E., Lee M., Okuro K., Kinbara K., Aida T., High-water-content mouldable hydrogels by mixing clay and a dendritic molecular binder. Nature 463, 339–343 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huang T., Xu H. G., Jiao K. X., Zhu L. P., Brown H. R., Wang H. L., A novel hydrogel with high mechanical strength: A macromolecular microsphere composite hydrogel. Adv. Mater. 19, 1622–1626 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haraguchi K., Takehisa T., Nanocomposite hydrogels: A unique organic–inorganic network structure with extraordinary mechanical, optical, and swelling/de-swelling properties. Adv. Mater. 14, 1120–1124 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sun T. L., Kurokawa T., Kuroda S., Ihsan A. B., Akasaki T., Sato K., Haque M. A., Nakajima T., Gong J. P., Physical hydrogels composed of polyampholytes demonstrate high toughness and viscoelasticity. Nat. Mater. 12, 932–937 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ash C., Trehalose confers superpowers. Science 358, 1398–1399 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Crowe J. H., Crowe L. M., Chapman D., Preservation of membranes in anhydrobiotic organisms: The role of trehalose. Science 223, 701–703 (1984). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Duong T., Barrangou R., Russell W. M., Klaenhammer T. R., Characterization of the tre locus and analysis of trehalose cryoprotection in Lactobacillus acidophilus NCFM. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72, 1218–1225 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Elbein A. D., Pan Y. T., Pastuszak I., Carroll D., New insights on trehalose: A multifunctional molecule. Glycobiology 13, 17R–27R (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hashimoto T., Horikawa D. D., Saito Y., Kuwahara H., Kozuka-Hata H., Shin-I T., Minakuchi Y., Ohishi K., Motoyama A., Aizu T., Enomoto A., Kondo K., Tanaka S., Hara Y., Koshikawa S., Sagara H., Miura T., Yokobori S.-i., Miyagawa K., Suzuki Y., Kubo T., Oyama M., Kohara Y., Fujiyama A., Arakawa K., Katayama T., Toyoda A., Kunieda T., Extremotolerant tardigrade genome and improved radiotolerance of human cultured cells by tardigrade-unique protein. Nat. Commun. 7, 12808 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Seki K., Toyoshima M., Preserving tardigrades under pressure. Nature 395, 853–854 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jain N. K., Roy I., Effect of trehalose on protein structure. Protein Sci. 18, 24–36 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Crowe L. M., Reid D. S., Crowe J. H., Is trehalose special for preserving dry biomaterials? Biophys. J. 71, 2087–2093 (1996). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Corradini D., Strekalova E. G., Stanley H. E., Gallo P., Microscopic mechanism of protein cryopreservation in an aqueous solution with trehalose. Sci. Rep. 3, –1218 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee S. L., Debenedetti P. G., Errington J. R., A computational study of hydration, solution structure, and dynamics in dilute carbohydrate solutions. J. Chem. Phys. 122, 204511 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lerbret A., Bordat P., Affouard F., Descamps M., Migliardo F., How homogeneous are the trehalose, maltose, and sucrose water solutions? An insight from molecular dynamics simulations. J. Phys. Chem. B 109, 11046–11057 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Branca C., Magazu S., Maisano G., Migliardo P., Anomalous cryoprotective effectiveness of trehalose: Raman scattering evidences. J. Chem. Phys. 111, 281–287 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Morelle X. P., Illeperuma W. R., Tian K., Bai R., Suo Z., Vlassak J. J., Highly stretchable and tough hydrogels below water freezing temperature. Adv. Mater. 30, 1801541 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gao H., Zhao Z., Cai Y., Zhou J., Hua W., Chen L., Wang L., Zhang J., Han D., Liu M., Jiang L., Adaptive and freeze-tolerant heteronetwork organohydrogels with enhanced mechanical stability over a wide temperature range. Nat. Commun. 8, 15911 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wieslander G., Norbäck D., Lindgren T., Experimental exposure to propylene glycol mist in aviation emergency training: Acute ocular and respiratory effects. Occup. Environ. Med. 58, 649–655 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hu C., Zhang Y., Wang X., Xing L., Shi L., Ran R., Stable, strain-sensitive conductive hydrogel with antifreezing capability, remoldability, and reusability. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 10, 44000–44010 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Han L., Liu K., Wang M., Wang K., Fang L., Chen H., Zhou J., Lu X., Mussel-inspired adhesive and conductive hydrogel with long-lasting moisture and extreme temperature tolerance. Adv. Funct. Mater. 28, 1704195 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 35.Delley B., From molecules to solids with the DMol 3 approach. J. Chem. Phys. 113, 7756–7764 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- 36.Delley B., Hardness conserving semilocal pseudopotentials. Phys. Rev. B. 66, 155125 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- 37.Perdew J. P., Burke K., Ernzerhof M., Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865–3868 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dereka B., Yu Q., Lewis N. H. C., Carpenter W. B., Bowman J. M., Tokmakoff A., Crossover from hydrogen to chemical bonding. Science 371, 160–164 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Steiner T., The hydrogen bond in the solid state. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 41, 48–76 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang E., Bai R., Morelle X. P., Suo Z., Fatigue fracture of nearly elastic hydrogels. Soft Matter 14, 3563–3571 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bai R., Yang J., Suo Z., Fatigue of hydrogels. Eur. J. Mech. A Solids 74, 337–370 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 42.Naseem A., Khan M. S., Ali H., Ahmad I., Jairajpuri M. A., Deciphering the role of trehalose in hindering antithrombin polymerization. Biosci. Rep. 39, (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Martínez-Martínez I., Trehalose: Is it a potential inhibitor of antithrombin polymerization? Biosci. Rep. 39, (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rivlin R., Thomas A. G., Rupture of rubber. I. Characteristic energy for tearing. J. Polym. Sci. 10, 291–318 (1953). [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhao X., Chen X., Yuk H., Lin S., Liu X., Parada G., Soft materials by design: Unconventional polymer networks give extreme properties. Chem. Rev. 121, 4309–4372 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chen C., Wang Z., Suo Z., Flaw sensitivity of highly stretchable materials. Extreme Mech. Lett. 10, 50–57 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 47.Long R., Hui C.-Y., Gong J. P., Bouchbinder E., The fracture of highly deformable soft materials: A tale of two length scales. Annu. Rev. Condens. Matter Phys. 12, 71–94 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gun’ko V. M., Savina I. N., Mikhalovsky S. V., Properties of water bound in hydrogels. Gels 3, 37 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Li Y., Hu C., Lan J., Yan B., Zhang Y., Shi L., Ran R., Hydrogel-based temperature sensor with water retention, frost resistance and remoldability. Polymer 186, 122027 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bai Y., Chen B., Xiang F., Zhou J., Wang H., Suo Z., Transparent hydrogel with enhanced water retention capacity by introducing highly hydratable salt. Appl. Phys. Lett. 105, 151903 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sapir L., Harries D., Linking trehalose self-association with binary aqueous solution equation of state. J. Phys. Chem. B. 115, 624–634 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sakai T., Matsunaga T., Yamamoto Y., Ito C., Yoshida R., Suzuki S., Sasaki N., Shibayama M., Chung U.-i., Design and fabrication of a high-strength hydrogel with ideally homogeneous network structure from tetrahedron-like macromonomers. Macromolecules 41, 5379–5384 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lin S., Ni J., Zheng D., Zhao X., Fracture and fatigue of ideal polymer networks. Extreme Mech. Lett. 48, 101399 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 54.Liu J., Lin S., Liu X., Qin Z., Yang Y., Zang J., Zhao X., Fatigue-resistant adhesion of hydrogels. Nat. Commun. 11, 1071 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Drury J. L., Dennis R. G., Mooney D. J., The tensile properties of alginate hydrogels. Biomaterials 25, 3187–3199 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Koshut W. J., Rummel C., Smoot D., Kirillova A., Gall K., Flaw sensitivity and tensile fatigue of poly(vinyl alcohol) hydrogels. Macromol. Mater. Eng. 306, 2000679 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 57.Li J., Illeperuma W. R., Suo Z., Vlassak J. J., Hybrid hydrogels with extremely high stiffness and toughness. ACS Macro Lett. 3, 520–523 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wegst U., Ashby M., The mechanical efficiency of natural materials. Philos. Mag. 84, 2167–2186 (2004). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Text

Figs. S1 to S20

Table S1

Movies S1 to S7