Abstract

Background

Discharge planning is a routine feature of health systems in many countries that aims to reduce delayed discharge from hospital, and improve the co‐ordination of services following discharge from hospital and reduce the risk of hospital readmission. This is the fifth update of the original review.

Objectives

To assess the effectiveness of planning the discharge of individual patients moving from hospital.

Search methods

We searched CENTRAL, MEDLINE, Embase and two trials registers on 20 April 2021. We searched two other databases up to 31 March 2020. We also conducted reference checking, citation searching and contact with study authors to identify additional studies.

Selection criteria

Randomised trials that compared an individualised discharge plan with routine discharge that was not tailored to individual participants. Participants were hospital inpatients.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently undertook data analysis and quality assessment using a pre‐designed data extraction sheet. We grouped studies by older people with a medical condition, people recovering from surgery, and studies that recruited participants with a mix of conditions. We calculated risk ratios (RRs) for dichotomous outcomes and mean differences (MDs) for continuous data using fixed‐effect meta‐analysis. When combining outcome data it was not possible because of differences in the reporting of outcomes, we summarised the reported results for each trial in the text.

Main results

We included 33 trials (12,242 participants), four new trials included in this update. The majority of trials (N = 30) recruited participants with a medical diagnosis, average age range 60 to 84 years; four of these trials also recruited participants who were in hospital for a surgical procedure. Participants allocated to discharge planning and who were in hospital for a medical condition had a small reduction in the initial hospital length of stay (MD − 0.73, 95% confidence interval (CI) − 1.33 to − 0.12; 11 trials, 2113 participants; moderate‐certainty evidence), and a relative reduction in readmission to hospital over an average of three months follow‐up (RR 0.89, 95% CI 0.81 to 0.97; 17 trials, 5126 participants; moderate‐certainty evidence). There was little or no difference in participant's health status (mortality at three‐ to nine‐month follow‐up: RR 1.05, 95% CI 0.85 to 1.29; 8 trials, 2721 participants; moderate certainty) functional status and psychological health measured by a range of measures, 12 studies, 2927 participants; low certainty evidence). There was some evidence that satisfaction might be increased for patients (7 trials), caregivers (1 trial) or healthcare professionals (2 trials) (very low certainty evidence). The cost of a structured discharge plan compared with routine discharge is uncertain (7 trials recruiting 7873 participants with a medical condition; very low certainty evidence).

Authors' conclusions

A structured discharge plan that is tailored to the individual patient probably brings about a small reduction in the initial hospital length of stay and readmissions to hospital for older people with a medical condition, may slightly increase patient satisfaction with healthcare received. The impact on patient health status and healthcare resource use or cost to the health service is uncertain.

Keywords: Aged; Aged, 80 and over; Humans; Middle Aged; Hospitals; Length of Stay; Patient Discharge; Patient Readmission; Patient Satisfaction; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic

Plain language summary

Discharge planning from hospital

What is the aim of this review

The aim of this review was to find out if discharge planning that is tailored to an individual improves the quality of health care delivered by reducing delayed discharge from hospital, reducing transfer back to hospital and improving patients' health status. We also wanted to know how much the intervention cost. We collected and analysed all relevant studies to answer this question. This is the fifth update of the original review.

Key messages

When people leave hospital with a personalised discharge plan there is probably a small reduction in length of stay, they are probably slightly less likely to be admitted to hospital after their discharge from hospital. There is little evidence on the impact on patient health status, patient satisfaction with the care received. The cost of discharge planning is uncertain.

What was studied in the review

Discharge planning is the development of a personalised plan that assesses a patient's health and social care needs prior to them leaving hospital, to support the timely transition between hospital and home or another setting and improve the organisation of post‐discharge services.

What are the main results of the review?

We found 33 trials that compared personalised discharge plans versus standard discharge care. This review indicates that a personalised discharge plan probably leads to a very small reduction in hospital length of stay and probably slightly reduces readmission rates for people who were admitted to hospital with a medical condition, and may increase patient satisfaction. There is little evidence on health status, or the cost of discharge planning to the health service.

How up‐to‐date is this review?

The review authors searched for studies that had been published up to April 2021.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings 1. Effect of discharge planning on patients admitted to hospital.

| Effect of discharge planning on patients admitted to hospital | ||||||

|

Patient or population: patients admitted to hospital with a medical condition (27 trials), with a mix of medical and surgical conditions (4 trials), following a fall (1 trial), with a psychiatric diagnosis (2 trials), with a mix of mental health and medical diagnosis.

Settings: hospital; North America (16 trials), Europe (13 trials), Asia (4 trials), South America (1 trial), Oceania (1 trial)

Intervention: discharge planning Comparison: usual care, mostly with some discharge planning but without a formal link through a coordinator to other departments and services | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No. of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Without discharge planning | With discharge planning | |||||

| Hospital length of stay Follow‐up: 3 to 6 months | Study population admitted with a medical condition | (MD ‐0.73, 95% CI ‐1.33 to ‐0.12) |

2113 (11 trials) |

⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderateb |

Gillespie 2009; Harrison 2002; Laramee 2003; Lindpaintner 2013; Moher 1992; Naughton 1994; Naylor 1994; Preen 2005; Rich 1993; Rich 1995; Sulch 2000 | |

| The mean hospital length of stay ranged across control groups from 5.2 to 12.4 daysa | The mean hospital length of stay in the intervention groups was 0.73 lower (95% CI 1.33 to ‐0.12 lower) | |||||

|

Unscheduled readmission Follow‐up: 2 weeks to 6 months |

Study population admitted with a medical condition | RR 0.89 (0.81 to 0.97) | 5126 (17 trials) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderateb | Balaban 2008; Bonetti 2018; Farris 2014; Goldman 2014; Harrison 2002; Jack 2009; Kennedy 1987; Lainscak 2013; Laramee 2003; Legrain 2011; Lisby 2019; Moher 1992; Naylor 1994; Nazareth 2001; Nguyen 2018; Rich 1993; Rich 1995 | |

| 271 per 1,000 | 242 per 1000 (200 to 263) | |||||

| Patient health status | Mortality (follow‐up 3 to 9 months) | |||||

| 110 per 1,000 | 115 per 1,000 | RR 1.05 (0.85 to 1.29) | 2721 (8 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝b moderate |

Goldman 2014; Lainscak 2013; Laramee 2003; Legrain 2011; Nazareth 2001; Nguyen 2018; Rich 1995; Sulch 2000 | |

| Functional status and psychological health (follow‐up 1 to 6 months) | ||||||

| Most studies reported little or no differences between groups for general and disease‐specific health‐related quality of life (Harrison 2002; Kennedy 1987; Lainscak 2013; Lisby 2019; Naylor 1994; Nazareth 2001; Nguyen 2018; Preen 2005; Weinberger 1996; measured with EQ‐5D‐3L, LTCIS, SF‐12, SF‐36, VAS). Two studies that recruited participants with heart failure reported less disability (MLHFQ; MD 8.59, 95% CI 4.02 to 13.16; Cajanding 2017) and better quality of life (CHFQ; MD 22.1, SD 20.8; Rich 1995) for those allocated to the intervention. Sulch 2000 recruited participants recovering from a stroke and reported that those allocated to the intervention scored worse on activities of daily living and quality of life (EQ‐5D), with little or no difference between groups for stroke‐related disability (Rankin score) and anxiety and depression symptoms (HADS). |

2927 (12 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowc |

||||

|

Satisfaction of patients, care givers and healthcare professionals Follow‐up: 2 weeks to 6 months Measured with PSQ, SF‐PSQ‐18, in‐house developed questions |

Four studies reported an increased level of satisfaction for participants allocated to the intervention group (Cajanding 2017; Laramee 2003; Moher 1992; Weinberger 1996), and three little or no difference (Nazareth 2001; (Lindpaintner 2013; Lisby 2019). One small study reported that care givers of participants allocated to the intervention group were more satisfied with the discharge process, and little or no difference for healthcare professionals (Lindpaintner 2013). | 756 participants when reported (8 trials) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very lowd |

Satisfaction was measured in different ways (SF‐PSQ‐18 Short‐Form Patient Questionnaire, PSQ Patient Satisfaction Questionnaire) and findings were not consistent across studies; 8/35 studies reported data for this outcome. | ||

| Healthcare resource use and costs | Eleven trials reported findings on an aspect of cost to the health service, it is uncertain whether there is a difference in hospital, primary or community care costs when discharge planning is implemented for patients with a medical condition (Farris 2014; Gillespie 2009; Goldman 2014; Jack 2009; Laramee 2003; Lisby 2019; Naughton 1994; Nazareth 2001; Rich 1995; Weinberger 1996), or who are in hospital for surgery (Naylor 1994). |

5220 participants (11 trials) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very lowd |

Healthcare resources that were costed and charges varied among trials. | ||

| *The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CHFQ: Chronic Heart Failure Questionnaire; CI: Confidence interval; EQ‐5D: European Quality of Life Questionnaire; HADS: Hospital Anxiety and Depression scale; LTCIS: Long Term Care Information System; MD: Mean difference; MLHFQ: Minnesota Living With Heart Failure Questionnaire; RR: Risk ratio; SF: Short Form Survey; VAS: Visual Analogue Scale. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High:This research provides a very good indication of the likely effect. The likelihood that the effect will be substantially different (i.e., large enough to affect a decision) is low. Moderate: This research provides a good indication of the likely effect. The likelihood that the effect will be substantially different is moderate. Low: This research provides some indication of the likely effect. However, the likelihood that it will be substantially different is high. Very low: This research does not provide a reliable indication of the likely effect. The likelihood that the effect will be substantially different is very high. | ||||||

a The range excludes length of stay of 45 days reported by Sulch, due to recruiting participants who were recovering from a stroke and had a longer length of stay.

b We downgraded the evidence to moderate due to imprecision

c We downgraded the evidence to low due to concerns about inconsistency and imprecision

d We downgraded the evidence to very low due to very serious inconsistency and imprecision

Background

A delayed discharge from hospital to home or another setting can lead to poorer patient outcomes, be a cause of distress to patients and their families (Mäkelä 2020), and increase the cost to the health system (Landeiro 2019). Recent trends to support timely discharge from hospital include targeting those patients who incur greater healthcare expenditures, strengthening arrangements for the transition from hospital to home and implementing policies such as discharge planning. Even a small reduction in hospital length of stay and readmission rates could have a substantial financial impact (Burgess 2014; Finkelstein 2020; Sezgin 2020),

Description of the condition

Delayed discharge from hospital occurs when a person is medically fit to be discharged home or another setting, but arrangements for transfer and subsequent care are not in place and the person remains in hospital. Delays can be due to incomplete assessment during the hospital admission, disruption of long‐standing care arrangements, difficulty accessing follow‐up health and social care or poor communication between the hospitals and community health and social care providers (NHS 2020; Bibbins‐Domingo 2019).

Description of the intervention

Discharge planning is the development of an individualised discharge plan for a patient prior to them leaving hospital for home. The discharge plan can be a stand‐alone intervention, may include post‐discharge support (Parker 2002; Phillips 2004) or may be embedded within another intervention. For example, as a component of stroke unit care (Langhorne 2020), as part of comprehensive geriatric assessment (Ellis 2017) or it may be part of a medicine review at the time a person transitions from hospital to home (Redmond 2016). Over the years there has been increased attention on medication errors that can occur at the time of discharge from hospital, with evidence indicating that errors are more likely to occur when a patient is transferred from one healthcare setting to another during admission (WHO 2019).

How the intervention might work

The aim of discharge planning is to improve the efficiency and quality of healthcare delivery by reducing delayed discharge from hospital, facilitating the transition of patients from hospital to a post‐discharge setting and providing patients with information about the management of their health problems. There is evidence to suggest that discharge planning (i.e. an individualised plan for a patient prior to them leaving hospital for home) combined with additional post‐discharge support can reduce unplanned readmission to hospital for patients with congestive heart failure (Phillips 2004). Discharge planning with or without post‐discharge follow‐up may improve patient outcomes and contain costs, by avoiding a prolonged admission to hospital and strengthening arrangements for subsequent health and social care (Balaban 2008; NHS Long Term Plan 2019). It is possible that discharge planning might have a differential effect for different populations, such as older people with complex healthcare needs compared with people admitted to a mental health facility or recovering from elective surgery. How healthcare is organised might also impact on the effectiveness of discharge planning, procedures may vary between specialities and healthcare professionals across hospitals and within the same hospital (Ubbink 2014).

Why it is important to do this review

Clinical guidance issued by professional and government bodies in the UK (RCP 2017; Dept of Health 2020), the USA (DHHS 2019), Australia (Health Direct 2020) and Canada (Health Qual Ontario 2013) highlight the importance of planning discharge as soon as a person is admitted to hospital, of involving a multidisciplinary team to provide a comprehensive assessment, communication with the patient and their caregivers, shared decision‐making, and liaising with health and social services in the community. We have conducted a systematic review of discharge planning to categorise the different types of study populations and discharge plans being implemented, and to assess the effectiveness of organising services in this way. The focus of this review is the effectiveness of discharge planning implemented in an acute hospital setting. This is the fifth update of the original review.

Objectives

To assess the effectiveness and cost to the health service of planning the discharge of individual patients moving from hospital.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised trials.

Types of participants

All patients in hospital (acute, rehabilitation or community) irrespective of age, gender or condition.

Types of interventions

We defined discharge planning as the development of an individualised discharge plan for a patient prior to them leaving hospital for home or residential care. Where possible, we divided the process of discharge planning according to the steps identified by Marks 1994:

preadmission assessment (where possible);

case finding on admission;

inpatient assessment and preparation of a discharge plan based on individual patient needs, for example a multidisciplinary assessment involving the patient and their family, and communication between relevant professionals within the hospital;

implementation of the discharge plan, which should be consistent with the assessment and requires documentation of the discharge process;

monitoring in the form of an audit to assess if the discharge plan was implemented.

We excluded studies from the review if they did not include an assessment or implementation phase in the discharge plan; if discharge planning appeared to be a minor part of a multifaceted intervention; or if the focus was on the provision of care after discharge from hospital.

The control group had to receive standard care with no individualised discharge plan.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

1. Hospital length of stay

2. Unscheduled readmission to hospital

3. Patient health status: mortality, functional status, psychological health

4. Satisfaction of patients, caregivers and healthcare staff

5. Healthcare resource use and costs

Secondary outcomes

6. Medication use for studies evaluating a pharmacist led discharge plan

7. Place of discharge

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the following databases on 20 April 2021:

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (2021, Issue 3)

MEDLINE, Ovid (2015 to 20 April 2021)

Embase, Ovid (2015 to 20 April 2021)

CINAHL, EBSCO (2015 to 31 March 2020)

PsycINFO, Ovid (2015 to 31 March 2020)

Searches were revised for this update by evaluating titles, abstracts and index terms (MeSH) of 29 included studies from previous versions of the review using the Yale MeSH analyzer (mesh.med.yale.edu/). Sources which had not yielded any unique studies over a number of iterations of the search were searched for this update in March 2020 but were not searched for the rerun in April 2021 (PsycINFO and CINAHL). Search strategies are comprised of natural language and controlled vocabulary terms. We applied no limits on language. Searches were run from 2015 onwards ‐ the date of publication of the previous version of the review. In databases where it was possible and appropriate, study design filters for randomised trials were used; in MEDLINE we used a modified version of the Cochrane Highly Sensitive Search Strategy for identifying randomised trials in MEDLINE: sensitivity‐ and precision‐maximi zing version (2008 revision) (Lefebvre 2021). Limits were used in Embase to remove MEDLINE records in order to avoid duplication in downloaded results. Remaining results were de‐duplicated in EndNote against each other and against results from searches conducted for previous versions of the review. All search strategies used in this version of the review are provided in Appendix 1. Search strategies and search methods used in previous versions of the review are published within those prior publications.

Searching other resources

We searched two trials registers on 20 April 2021:

US National Institutes of Health trial register (ClinicalTrials.gov)

WHO ICTRP (World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform) (trialsearch.who.int/)

We reviewed systematic reviews retrieved by the searches, as well as the reference lists of all included studies. When necessary, we contacted individual trialists to clarify issues and to identify unpublished data.

Data collection and analysis

For this update, we followed the same methods defined in the protocol and used in previous versions of this systematic review. We created a summary of findings table using the following outcomes: unscheduled hospital readmission, hospital length of stay, health status, satisfaction and costs. We used the five GRADE considerations (study limitations, consistency of effect, imprecision, indirectness, and risk of bias) to assess the certainty of the evidence as it relates to the main outcomes (Guyatt 2008). We used methods and recommendations described in Section 8.5 and Chapter 12 of the Cochrane Handbook (Higgins 2011). We justified all decisions to down‐ or up‐grade the certainty of evidence using footnotes to aid readers' understanding of the review where necessary.

Selection of studies

For this update, two review authors (of DCGB, IC, NL, LC and SS) read the abstracts in the records retrieved by the electronic searches to identify publications that appeared to be eligible for this update, and two (of DCGB, IC, NL, LC, SS) independently assessed the full text of all potentially relevant papers to select studies for inclusion. We settled any disagreements by discussion. For previous versions of this review, please see details of those involved in selecting studies in the Acknowledgements section of this review.

Data extraction and management

For this update, two review authors working independently (DCGB, ACB) extracted data from the studies included in this update using a data extraction form developed by EPOC, modified and amended for the purposes of this review (EPOC 2015); these were reviewed by SS. We extracted information on study characteristics (citation, aim, setting, design, risk of bias, study duration, ethical approval, funding sources), participant characteristics (method of recruitment, inclusion/exclusion criteria, study population health problems and diagnosis, total number, withdrawals and number lost to follow‐up, socio‐demographic indicators), intervention (setting, preadmission assessment, case finding on admission, inpatient assessment and preparation of discharge plan, implementation of discharge plan, monitoring phase, and comparison), and outcomes.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

For this update, three review authors (DCGB, ACB or SS) independently assessed risk of bias for random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding, incomplete outcome data, selective reporting and baseline data using Cochrane's risk of bias tool (Higgins 2011). Each domain was assessed as being at high, low or unclear risk of bias. Disagreements were resolved by discussion with SS. We prioritised the main outcomes length of stay and readmission for our overall assessment of bias for each study.

Measures of treatment effect

We calculated risk ratios (RRs) for unscheduled readmissions and mortality with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for all point estimates, values less than 1 indicated outcomes favouring discharge planning. We calculated mean differences (MDs) with 95% CIs for the hospital length of stay, and reported the results from the individual studies for the remaining outcomes.

Unit of analysis issues

All the included studies were parallel randomised trials, where participants were individually allocated to the treatment or control groups.

Dealing with missing data

We contacted investigators for missing data; we did not include unpublished data in this update.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We quantified heterogeneity among trials using the I2 statistic and Cochrane's Q test (Cochran 1954). The I2 statistic quantifies the percentage of the total variation across studies that is due to heterogeneity rather than chance (Higgins 2003); smaller percentages suggest less observed heterogeneity (Higgins 2019).

Assessment of reporting biases

We constructed funnel plots for the meta‐analysis of the main outcomes, hospital length of stay and readmission (Higgins 2019).

Data synthesis

We calculated a summary statistic for each outcome when there were sufficient data, using Review Manager 5.4 (Review Manager 2020). We used a fixed‐effect model unless heterogeneity was detected, using an I2 of greater than 60% as a rough guide of substantial heterogeneity. We used the Sythesis Without Meta‐analysis and EPOC guidance to summarise the findings if it was not possible to combine data for meta‐analysis (Campbell 2020; EPOC 2017), by reporting the range of estimates of effect and level of uncertainty for each outcome.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

In order to reduce differences between studies, we grouped trial results by participants' condition (medical, requiring surgery, admitted to a mental health facility or studies that recruited participants with a mix of conditions), as the discharge planning needs for these groups might differ. We extracted data on the elements of the intervention with a focus on the timing of the discharge plan, who was the discharge lead, the inclusion of patient education and how the discharge plan was implemented.

Sensitivity analysis

We did not conduct sensitivity analysis.

Summary of findings and assessment of the certainty of the evidence

We created a summary of findings table using GRADEpro GRADEpro GDT 2021) for the main outcomes of hospital length of stay, unscheduled readmission to hospital, patient health status, satisfaction of patients, caregivers and healthcare professionals, healthcare resource use and costs.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

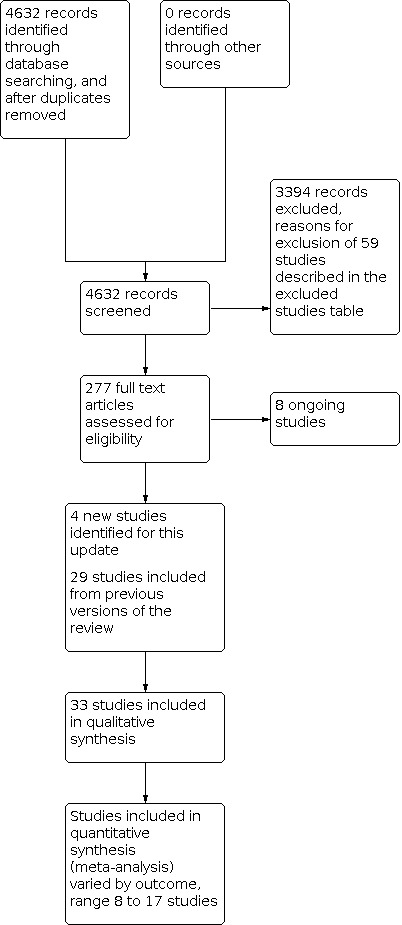

We retrieved 4632 results from electronic searches (Figure 1). Of these, we screened the full text of 277 records and describe reasons for excluding 59 of the studies. We excluded one study that had previously been included due the focus on an occupational therapy post‐discharge home visit (Pardessus 2002), we included four new studies in this update (Bonetti 2018; Cajanding 2017; Lisby 2019; Nguyen 2018), and added these to the 29 trials previously identified (Balaban 2008; Bolas 2004; Eggink 2010; Evans 1993; Farris 2014; Gillespie 2009; Goldman 2014; Harrison 2002; Hendriksen 1990; Jack 2009; Kennedy 1987; Kripalani 2012; Lainscak 2013; Laramee 2003; Legrain 2011; Lin 2009; Lindpaintner 2013; Moher 1992; Naji 1999; Naughton 1994; Naylor 1994; Nazareth 2001; Parfrey 1994; Preen 2005; Rich 1993; Rich 1995; Shaw 2000; Sulch 2000; Weinberger 1996), for a total of 33 studies (12,242 participants, average sample size 370 participants). One of the trials included in the review was translated from Danish to English (Hendriksen 1990). Follow‐up times varied from five days to 12 months.

1.

PRISMA flow diagram

Included studies

Twenty‐six of the 33 trials recruited participants with a medical condition (Balaban 2008; Bolas 2004; Bonetti 2018; Cajanding 2017; Eggink 2010; Farris 2014; Gillespie 2009; Goldman 2014; Harrison 2002; Jack 2009; Kennedy 1987; Kripalani 2012; Lainscak 2013; Laramee 2003; Legrain 2011; Lindpaintner 2013; Lisby 2019; Moher 1992; Naughton 1994; Nazareth 2001; Nguyen 2018; Preen 2005; Rich 1993; Rich 1995; Sulch 2000; Weinberger 1996), with an average age range of 60 to 84 years; nine of these trials recruited participants with heart‐related problems (heart failure or acute coronary syndrome) (Bonetti 2018; Cajanding 2017; Eggink 2010; Harrison 2002; Kripalani 2012; Laramee 2003; Nguyen 2018; Rich 1993; Rich 1995), one recruited participants recovering from a stroke (Sulch 2000), and one trial included participants with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (Lainscak 2013). Four trials recruited participants with a mix of medical and surgical conditions (Evans 1993; Hendriksen 1990; Naylor 1994; Parfrey 1994), one with older people (average age 78 years) admitted to hospital following a hip fracture (Lin 2009), and two with participants who were receiving care in a mental health facility (Naji 1999; Shaw 2000). Two trials used a questionnaire designed to identify participants likely to require discharge planning (Evans 1993; Parfrey 1994). Three trials recruited an ethnically diverse low‐income and under‐served population (Balaban 2008; Goldman 2014; Jack 2009).

The majority of trials evaluated a discharge planning intervention that aimed to facilitate the co‐ordination of post‐discharge care and improve communication between the hospital, primary care and community services to aid the transition of patients from hospital to their discharge destination (see Characteristics of included studies and Table 2). In all but three trials (Evans 1993; Naji 1999; Parfrey 1994), the discharge planning intervention included an education component that provided patients with information of their health condition, medicines and post‐discharge arrangements. In 21 trials a review of medicines was described as one element of the discharge planning intervention, and in nine studies medicine review and reconciliation was the focus of the intervention (Bolas 2004; Bonetti 2018; Eggink 2010; Farris 2014; Gillespie 2009; Kripalani 2012; Nazareth 2001; Nguyen 2018; Shaw 2000).

1. Intervention characteristics.

| Study ID | Components of the assessment and implementation of the discharge plan | Aim, focus and content of the discharge plan | Follow‐up as part of the discharge planning intervention | Control group care |

| Balaban 2008 |

Discharge planning lead: discharge planner registered nurse Timing of discharge plan: enrolled at admission to hospital Education:a patient discharge form for the patient that included information about the patient's health problem/diagnosis, medications, and follow‐up care Implementation of the discharge plan: discharge form was sent electronically to the primary care team to become part of the permanent medical records. |

A discharge plan to improve communication between inpatient and outpatient care teams abd to reconnect patients who lived at home with their primary care team, using a structure‐process‐outcome approach. The intervention was structured for a culturally diverse population. | Telephone call: the day after discharge from hospital, from the primary care nurse | No communication between hospital and primary care nurse, handwritten discharge instruction in English, communication with hospital and primary care physician as required. |

| Bolas 2004 |

Discharge planning lead: one full‐time clinical pharmacist clinical pharmacy service Timing of discharge plan: within 48 hours of admission to hospital Education: patient counselling to explain changes to medication Implementation of the discharge plan: daily contact with the patient to explain changes to treatement, medication history, personalised medication record, discharge letter outlining drug history and changes to medication during hospital and variances to discharge prescription. This was faxed to GP and community pharmacist. Personalised medicine card, discharge counselling, labelling of dispensed medications under the same headings for follow‐up. |

A hospital based community liaison pharmacist to improve the management of medicines and communication between secondary and primary care during transition from secondary to primary care. | Medicines help line | Standard clinical pharmacy service that did not include discharge counselling |

| Bonnetti 2018 |

Discharge planning lead: pharmacist‐led medication counselling Timing of discharge plan: recruited when admitted to hospital, review of discharge medications Education: verbal counseling was delivered by the pharmacists to patients or their caregivers, which included explanations about the indications, benefits, therapeutic targets, doses, dosing schedule, routes, storage, length of therapy, refill pharmacy, and possible ADEs of each prescribed drug. Implementation of the discharge plan: All pharmacist interventions followed a structured format. |

A pharmacist led review of medicines to improve communication about medicines during transition from hospital. | Patients were contacted by telephone three and 15 days post‐discharge to reinforce the previous counseling session. | Standard care from pharmacists and other healthcare providers |

| Cajanding 2017 |

Discharge planning lead: cardiovascular nurse practitioner led structured discharge plan Timing of patient involvement with the discharge plan: the second day of a hospital admission Education: individualized lecture type discussion, provision of feedback, integrative problem solving, goal setting, and action planning at 3 consecutive daily sessions lasting between 30 to 45 minutes Implementation of the discharge plan: a structured programme based from the guidelines set by the American Heart Association, the National Heart Foundation of Australia, and the Philippine Heart Association. |

A nurse led structured discharge programme to improve the quality of care and support the transition from hospital to home | Telephone at 3 and 15 days for the intervention group | Usual care based on the Philippine Heart Association clinical practice guidelines |

| Eggink 2010 |

Discharge planning lead: clinical pharmicist Timing of patient involvement with the discharge plan: at discharge Education: none Implementation of the discharge plan: verbal and written information about (side) effects of, and changes in, their in hospital drug therapy from a clinical pharmacist upon hospital discharge and the discharge medication list was faxed to the community pharmacist, a copy was provide to the patient to give to the GP. |

A multifaceted clinical pharmacist discharge service on the number of medications discrepancies after discharge, recruited participants had 5 + medicines prescribed | Not reported | Usual care |

| Evans 1993 |

Discharge planning lead: not clear Timing of patient involvement with the discharge plan: recruited patients screened at admission for risk of adverse hospital outcome and to minimise inappropriate referrals to discharge planning; discharge planning implemented on day 3 of hospital admission Education: not reported Implementation of the discharge plan: referred to a social worker, assessment of support systems, living situation, finances and areas of need. Plans were implemented with measurable goals. |

General discharge plan | Not reported | Could be referred for discharge planning, usually on day 9 of admission |

| Farris 2014 |

Discharge planning lead: pharmacist case manager Timing of patient involvement with the discharge plan: day 2 or 3 of admission Education: medication counselling to improve medication adherence, every 2 to 3 days, and discharge counselling Implementation of the discharge plan: a discharge medication list and counselling on goals of treatment, medication and barriers to adherence. Primary care provider and community pharmacist received a copy of the discharge plan within 24 hours of discharge and usually within 6 hours, it included the discharge medication list, plans for dosage adjustments and monitoring, recommendations for preventing adverse drug events, with patient specific concerns such as adherence or cost issues highlighted. |

To improve medication related outcomes during transitions of care | Telephone call 3 to 5 days post‐discharge | Usual care was medication reconciliation at admission according to hospital policy, nurse discharge counseling and a discharge medication list for patients. The usual care discharge summary was transcribed and received in the mail by the primary |

| Gillespie 2009 |

Discharge planning lead: clinical pharmicists Timing of involvement with the discharge plan: at admission Education: education provided during the hospital admission, a review of medicines and discharge counselling Implementation of discharge plan: medicine review, patient provided with a copy of the discharge letter. The pharmacist provided a comprehensive account of all changes in drug therapy during the hospital stay, including the rationale behind medication decisions, monitoring needs, and expected therapeutic goals. Drug related problems were listed with suggested actions. The physician responsible for the patient on the ward was required to approve the contents of the pharmacist’s discharge letter before it was sent to the patient’s general practitioner with the original discharge letter. The pharmacists’ discharge letters were not given to the patients. |

To reduce drug related problems, increase patient safety and reduce use of hospital care in people aged 80 years and older | Telephone call 2 months post‐discharge to assess the management of medicines | Standard care from nurse or physician, pharmacist not involved |

| Goldman 2014 |

Discharge planning lead: registered nurse, included native Spanish and Chinese speakers Timing of involvement with the discharge plan: patients who had been admitted in the previous 24 hours were seen by the discharge planning registered nurse Education: disease‐specific patient education that included symptom recognition, medication reconciliation and strategies to navigate the health system. Motivational interviewing techniques and coaching to promote patient engagement. A study RN supplemented verbal instructions with language‐concordant written materials (30). A study RN reinforced teaching using the “teach‐back” method to ensure comprehension (31) Implementation of discharge plan: the discharge planning study registered nurse met with the patient and contacted the patients’ primary care providers to supply the inpatient physicians’ contact information. |

A discharge planning nurse led intervention to facilitate the transition from hospital to home | Study nurse practitioners visited patients within 24 hours of discharge, and called patients on days 1 to 3 and 6 to 10 after discharge. | The bedside RN's review of the discharge instructions, received by all patients. If requested by the medical team, the hospital pharmacy provided a 10 day medication supply and a social worker assisted with discharge. The admitting team was responsible for liaising with the patients' PC |

| Harrison 2002 |

Discharge planning lead: nurse led Timing of involvement with the discharge plan: within 24 hours of Education: a structured evidence based protocol for counselling and education to support heart failure self‐management Implementation of discharge plan: comprehensive discharge plan, hospital and community nurse liaison, standard discharge planning + a comprehensive program that added support to improve the transfer from hospital to home. Hospital and community nurses met to focus on the ‘outreach’ from the hospital and ‘in‐reach’ from the community during the transition. An inter‐sectoral continuity of care framework was used to identify gaps to specifically address 3 major aspects of a hospital‐to‐home transition: (1) supportive care for self‐management; (2) linkages between hospital and home nurses and patients; and (3) the balance of care between the patient and family and professional providers |

A nurse led discharge plan to improve the transition between hospital settings. | Telephone call within 24 hours of discharge | Usual home care visits, available to intervention group |

| Hendriksen 1990 |

Discharge planning lead: project nurse Timing of involvement with the discharge plan: at the time of admission Education: health condition and discharge arrangements Implementation of the discharge plan: patients had daily contact with the project nurse who discussed their illness with them and discharge arrangements; liaison between hospital and primary care staff. |

A co‐ordinated transfer from hospital to home for older people. | Project nurse, a maximum of two visits after discharge | Usual care |

| Jack 2009 |

Discharge planning lead: nurse discharge advocate (DA) Timing of involvement with the discharge plan: Education: the DA used scripts from the training manual to review the contents of an after hospital care plan with the patient. Implementation of the discharge plan: with information collected from the hospital team and the participant, the DA created the after‐hospital care plan (AHCP), which contained medical provider contact information, dates for appointments and tests, an appointment calendar, a colour‐coded medication schedule, a list of tests with pending results at discharge, an illustrated description of the discharge diagnosis, and information about what to do if a problem arises. Information for the AHCP was manually entered into a Microsoft Word template, printed, and spiral‐bound to produce an individualised, colour booklet. On the day of discharge the AHCP and discharge summary were faxed to the primary care provider. |

Reengineered hospital discharge to minimize hospital utilisation after discharge. | A clinical pharmacist telephoned the participants 2‐4 days after the index discharge to reinforce the discharge plan by using a scripted interview. The pharmacist had access to the AHCP and hospital discharge summary and, over several days, made at least 3 attempts to reach each participant. The pharmacist asked participants to bring their medications to the telephone to review them and address medication‐related problems; the pharmacist communicated these issues to the PCP or DA | Usual care. |

| Kennedy 1987 |

Discharge planning lead: gerontology clinical nurse specialist (GCNS) Timing of involvement with the discharge plan: during the hospital admission Education: focused on explaining and clarifying the discharge plan Implementation of the discharge plan: a comprehensive discharge planning protocol (CDPP) was developed for use by the Gerontological Clinical Nurse Specialist (GCNS). Components of the assessment included: health status, orientation level, knowledge and perception of health status, resource use pattern, functional status, skill level, motivation level, and sociodemographic data. The patient's level of dependency was measured using the Long‐Term Care Information System (LTCIS). The GCNS met with the patient and family, physician, and other health care providers to identify resources and support networks for the patient postdischarge. A summary of the assessment information and potential care needs were entered in the progress notes of the patient's chart.The GCNS assisted in the coordination of services. |

A comprehensive discharge planning protocol to improve the health delivered to older people in hospital. | One follow‐up visit to assess the arrangements and care delivered. | Discharge arranged by the primary nurse. |

| Kripalani 2012 |

Discharge planning lead: a pharmacist TIming of patient involvement with the discharge plan: at enrolment to the study during a patients admission to hospital Education: one or two counselling sessions to the patient by the pharmacist, that accounted for the patient's health literacy and aimed to support adherence and minimize adverse effects. Pharmacists used 'teach‐back' to confirm understanding. Implementation of the discharge plan: pharmacist assisted medication reconciliation, tailored inpatient counselling, provision of low‐literacy adherence aids. The pharmacists communicated with the treating physicians to resolve any clinically relevant, unintentional medication discrepancies. |

A tailored intervention to reduce medication errors at and after hospital discharge. | Telephone follow‐up after discharge by a research coordinator, follow‐up call by a pharmacist to address any issues in collaboration with the treating inpatient and outpatient physicians. | Medicine reconciliation and discharge counselling |

| Lainscak 2013 |

Discharge planning lead: a discharge co‐ordinator Timing of patient involvement with the discharge plan: within 48 hours of admission to hospital Education: yes Implementation of the discharge plan: the discharge coordinator assessed the patient situation and home care needs to identify any problems and specific needs. Patients and caregivers were actively involved in the discharge planning process, which was communicated and discussed with community care/home care nurse, general practitioner, social care worker, physiotherapist, and other providers of home services as appropriate to provide continuity of care and care coordination across different levels of health care. |

To coordinate discharge from hospital to post‐discharge care to reduce hospitalizations. | Discharge coordinator called the patient 48 hours after discharge to check adjustment to home environment and additional needs, phone calls continued up to 7 to 10 days after discharge when a home visit was scheduled. | Usual care, routine patient education with written and verbal information about COPD, supervise inhaler use, respiratory physiotherapy as indicated, and disease related communication between medical staff with patients and their caregivers |

| Laramee 2003 |

Discharge planning lead: heart failure nurse case manager Timing of patient involvement with the discharge plan: during admission Education: a 15 page booked on heart failure to support self‐management. Individualised and family education. Implementation of the discharge plan: early discharge planning and coordination of care; facilitated communication between the hospital team and the patient, involved the patient and family in developing a care plan; review and monitoring of medicines and appropriate recommendations. |

Hospital based nurse led case management to co‐ordinate care and reduce hospital utilization. | 12 weeks of telephone follow‐up | Usual care |

| Legrain 2011 |

Discharge planning lead: a dedicated geriatrician Timing of patient involvement with the discharge plan: during admission Education: education on self‐management of disease Implementation of the discharge plan: comprehensive chronic medication review according to geriatric prescribing principles, and detailed transition‐of care‐communication with outpatient health professionals. |

To co‐ordinate a patient centred mult‐modal comprehensive discharge plan for older people to reduce preventable readmission, depression and protein‐energy malnutrition. | Not reported | Usual care in an acute geriatrician unit |

| Lin 2009 |

Discharge planning lead: nurse led Timing of patient involvement with the discharge plan: during the hospital admission Education: not reported Implementation of the discharge plan: structured assessment of discharge planning needs, systematic individualised nursing instruction based on the patient’s individual needs, monitoring services and coordinated resources and arranging of referral placements for each patient. |

To improve discharge planning to meet care needs after discharge for older people admitted to hospital with a hip fracture. | Two home visits post‐discharge to provide support and consultation | Unstructured discharge instructions without following a standardised procedure |

| Lindpainter 2013 |

Discharge planning lead: nurse Timing of patient involvement with the discharge plan: during admission Education: yes Implementation of the discharge plan: included discharge diagnoses, medication, and plans for follow‐up and home care sent on the day of discharge by to the primary care physician and the local visiting nurse organization. This discharge fax supplemented the hospital discharge summary generated as usual by the staff physician in both the intervention and control groups. |

To co‐ordinate care to reduce adverse events and cost | Telephone access via a pager and home visit if required | Standard discharge fax to primary care |

| Lisby 2019 |

Discharge planning lead: nurse Timing of patient involvement with the discharge plan: Education: included assessment of patients' understanding of their discharge recommendations that included medicines Implementation of the discharge plan: an assessment of the patient’s overall situation and requirement for additional healthcare and help, a review of medicines, their comprehension of discharge recommendations, a simple discharge letter targeting the individual patient’s health literacy and a follow‐up telephone call. |

To co‐ordinate care to increase post‐discharge safety and reduce readmissions. | Two week post‐discharge telephone call | Standard discharge letter provided to the primary care physician, the patient sometimes received a copy. |

| Moher 1992 |

Discharge planning lead: a nurse Timing of patient involvement with the discharge plan: shortly after admission to clinical unit. Education: not reported Implementation of the discharge plan: by a nurse co‐ordinator. |

To co‐ordinate and facilitate a discharge plan, tests and procedures, liaise with members of the clinical team and to collect and collate patient information. | Not included | Standard care |

| Naji 1999 |

Discharge planning lead: Psychiatrist Time of patient involvement with the discharge plan: ‐ Education: ‐ Implementation of the discharge plan: psychiatrist telephoned GP to discuss patient and make an appointment for the patient to see the GP within 1 week following discharge. A copy of the discharge summary was given to the patient to hand‐deliver to the GP and a copy was posted to the GP. |

To optimise communication between secondary and primary care at the time of discharge. | Not included | A standard discharge summary |

| Naughton 1994 |

Discharge planning lead: nurse Timing of discharge plan: at admission Education: yes Implementation of discharge plan: implemented at the time of admission; team meetings with the GEM and nurse specialist and physical therapist took place twice a week to discuss patients' medical condition, living situation, family and social supports, and patient and family's understanding of the patient's condition. The social worker was responsible for identifying and co‐ordinating community resources and ensuring the post‐discharge care was in place at the time of discharge and 2 weeks later. The nurse specialist co‐ordinated the transfer to home healthcare. Patients who did not have a primary care provider received outpatient care at the hospital. |

To build on geriatric management through a care plan that included co‐ordination of post‐discharge care. | Routine follow‐up that was not part of the discharge plan | Standard care |

| Naylor 1994 |

Discharge planning lead: nurse Timing of discharge plan: at admission Education: yes Implementation of discharge plan: 1) comprehensive initial and ongoing assessment of the discharge planning needs of the elderly patient and his or her caregiver; 2) development of a discharge plan in collaboration with the patient, caregiver, physician, primary nurse, and other members of the health care team; 3) validation of patient and caregiver education; 4) coordination of the discharge plan throughout the patient's hospitalization and through 2 weeks after discharge; 5) interdisciplinary communication regarding discharge status; and 6) ongoing evaluation of the effectiveness of the discharge plan. |

Timely discharge and facilitate post‐discharge care. | Telephone advise was available for up to two weeks after discharge and the nurse initiated two telephone calls during the first 2 weeks after discharge. | Routine discharge plan that was used for all patients |

| Nazareth 2001 |

Discharge planning lead: hospital and community pharmacists offered an integrated discharge plan. Timing of discharge plan: not clear. Education: the hospital pharmacist provided patients with information on their medicines and liaised with their carers and community professionals when appropriate, counselled patients and their caregivers on the purpose of the medicines, doses and how to dispose of excess medicines and provided carers and health professionals with a copy of the discharge plan. Implementation of discharge plan: Medication review and counselling, the hospital pharmacist assessed the patient's medication and the ability of the patient to manage their medication, provided medicine aids such as large print and special labels. |

Co‐ordination by hospital and community pharmacists to improve care of older people who are prescribed four or more drugs and optimise communication between primary and secondary care professionals | A pharmacist visited the patient at home two weeks after discharge from hospital to review medicines. | Standard discharge letter with diagnosis, investigations and medication, this did not include a review of medicines or a post‐discharge follow‐up visit. |

| Nguyen 2018 |

Discharge planning lead: hospital pharmacist TIming of discharge plan: one week before discharge Education: advise on their condition (acute coronary syndrome), risk factors, prevention; experience of medicines, medication aids, teaching back and correcting misunderstandings. Implementation of the discharge plan: Medication review and counselling, a multi‐faceted intervention of two counselling sessions to assess patients knowledge of their condition (acute coronary syndrome). |

A multi‐faceted intervention to enhance medication adherence, and reduce mortality and hospital readmission | Two weeks after discharge a 30 minute telephone call by a pharmacist to assess general and medication issues, provide tailored advice, teaching back and correcting misunderstanding | Standard care |

| Parfrey 1994 |

Discharge planning lead: member of the multi‐disciplinary team Timing of discharge plan: at admission Education: Implementaiton of the discharge plan: a 1‐page, 65‐item questionnaire was used to identify patients for early discharge planning. |

Early identification of patients for dicharge planning to reduce hospital length of stay | No | Standard discharge arrangements |

| Preen 2005 |

Discharge planning lead: multidisciplinary discharge care planning with primary care providers Timing of discharge plan: 24‐48 hours prior to discharge Education: patients were involved in identifying problems and goals Implementation of the discharge plan: problems and goals identified with the patient and carer, community service providers were identified who met patient needs and who were accessible.The discharge plan was faxed to the GP and all service providers identified on the care plan. |

A discharge care planning model to provide quality discharge arrangements and facilitate continuity of care and communication between the hospital and primary care physician | GP scheduled a consultation (within 7 d postdischarge) for patient review | Standard care that included a discharge summary provide to the patients and GP |

| Rich 1993 |

Discharge planning lead: cardiovascular specialist nurse Timing of discharge plan: early in the hospital admission Education: education about heart failure, treatment plan, diet and medicines using a 5 page guide Implementation of the discharge plan: review of medicines with recommendations to support compliance and reduce adverse effects, early discharge planning, review by social worker and home care team. The discharge plan was sent to the home care division. |

To facilitate discharge planning and ease the transition from hospital to home | Home care visited the patient at home within 48 hours of discharge and two more times during the first week, and then at regular intervals. | Standard care, without the education materials or formal medication review |

| Rich 1995 |

Discharge planning lead: cardiovascular specialist nurse Timing of discharge plan: early in the hospital admission Education: education about heart failure, treatment plan, diet and medicines using a 5 page guide Implementation of the discharge plan: review of medicines with recommendations to support compliance and reduce adverse effects, early discharge planning, review by social worker and home care team. The discharge plan was sent to the home care division. |

Reduce the risk of readmission | Home care visited the patient at home within 48 hours of discharge and two more times during the first week, and then at regular intervals. | Standard care, without the education materials or formal medication review |

| Shaw 2000 |

Discharge planning lead: hospital pharmacist Timing of discharge plan: during hospital admission Education: patient knowledge of illness and medicines was assessed by a questionnaire, and information was provided Implementation of the discharge plan: Medication review and counselling, a checklist was used to identify needs, details of the treatment plan were provided and provided to the patient's community pharmacist |

To identify medication problems experienced by patients | Domiciliary visits at 1, 4 and 12 weeks to assess knowledge and continuing care needs. | Standard care |

| Sulch 2000 |

Discharge planning lead: senior nurse with multi‐disciplinary team Timing of the discharge plan: day 5 to 6 of hospital admission Education: patient and carer education about the care plan and rehabilitation process, medicines, prognosis and related health problems Implementation of the discharge plan: discharge plan was revised during the hospital stay, the plan included discharge options and a date of discharge |

An integrated care pathway to reduce hospital length of stay in people with a stroke and having specialist rehabilitation | Routine follow‐up that was not part of the discharge plan | Standard multi‐disciplinary care |

| Weinberger 1996 |

Discharge planning lead: primary care nurse Timing of discharge plan: three days before discharge Education: patients were provided with educational material. Implementation of the discharge plan: assessment of post‐discharge needs, listed medical problems, assigned the patient to a primary care physician. |

Targetted people with diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or heart failure who were at risk of readmission. Aimed to reduce readmission by strengthening the planning of post‐discharge care | Primary nurse telephoned the patient 2 days after discharge, patient given an appointment to attend the primary care clinic within one week of discharge. | Standard care, did not have access to primary care nurse and did not receive supplemental education or assessment of needs beyond usual care. |

The discharge plan was implemented at varying times during a participant's stay in hospital, from admission to three days prior to discharge. Of the 33 included trials, 15 followed up after discharge with a telephone call (Balaban 2008; Bolas 2004; Bonetti 2018; Cajanding 2017; Farris 2014; Gillespie 2009; Harrison 2002; Jack 2009; Kripalani 2012; Lainscak 2013; Laramee 2003; Lin 2009; Lindpaintner 2013; Nguyen 2018; Weinberger 1996), five offered a home visit (Hendriksen 1990; Kennedy 1987; Lindpaintner 2013; Naylor 1994; Shaw 2000), two scheduled primary care appointments (Preen 2005; Weinberger 1996), and13 did not report any form of follow‐up (Eggink 2010; Evans 1993; Goldman 2014; Legrain 2011; Lisby 2019; Moher 1992; Naji 1999; Naughton 1994;Nazareth 2001; Parfrey 1994; Rich 1993; Rich 1995; Sulch 2000).

In 17 trials discharge planning was nurse‐led (Balaban 2008; Cajanding 2017; Goldman 2014; Harrison 2002; Hendriksen 1990; Jack 2009; Kennedy 1987; Laramee 2003; Lin 2009; Lindpaintner 2013; Lisby 2019; Moher 1992; Naylor 1994; Rich 1993; Rich 1995; Sulch 2000; Weinberger 1996), in nine it was led by a pharmacist (Bolas 2004; Bonetti 2018; Eggink 2010; Farris 2014; Gillespie 2009; Kripalani 2012; Nazareth 2001; Nguyen 2018; Shaw 2000), in three a member of the multidisciplinary team or a discharge co‐ordinator (Lainscak 2013; Naughton 1994; Parfrey 1994), in one a psychiatrist (Naji 1999), a geriatrician (Legrain 2011) and for one the lead was not reported (Evans 1993).

Twenty‐four trials described the control group as receiving usual care with some discharge planning, that might be limited to a discharge letter, but without a formal link through a co‐ordinator to other departments and services, although other services were available on request from nursing or medical staff (Balaban 2008; Bonetti 2018; Cajanding 2017; Eggink 2010; Evans 1993; Gillespie 2009; Goldman 2014; Harrison 2002; Hendriksen 1990; Jack 2009; Laramee 2003; Legrain 2011; Lin 2009; Lisby 2019; Moher 1992; Naji 1999; Naylor 1994; Naughton 1994; Parfrey 1994; Preen 2005; Rich 1993; Rich 1995; Sulch 2000; Weinberger 1996). The control groups in nine trials that evaluated the effectiveness of a pharmacy discharge plan did not have access to a medicine review discharge plan by a pharmacist (Bolas 2004;Bonetti 2018; Eggink 2010; Farris 2014; Gillespie 2009; Kripalani 2012; Nazareth 2001; Nguyen 2018; Shaw 2000). Two trials considered the potential influence of language fluency (Balaban 2008; Goldman 2014), and two health literacy (Jack 2009; Kripalani 2012).

Excluded studies

The main reason for excluding studies was due to the intervention including the delivery of post‐discharge care, such as augmented home care, or being a small part of a multi‐component intervention (Characteristics of excluded studies).

Risk of bias in included studies

Risk of bias assessments are graphically displayed in Figure 2.

2.

Methodological quality summary: review authors' judgements about each methodological quality item for each included study.

Allocation

Twenty‐five trials reported adequate random sequence generation (Bolas 2004; Bonetti 2018; Cajanding 2017; Eggink 2010; Farris 2014; Gillespie 2009; Goldman 2014; Harrison 2002; Jack 2009; Kennedy 1987; Kripalani 2012; Lainscak 2013; Legrain 2011; Lindpaintner 2013; Lisby 2019; Moher 1992; Naji 1999; Naughton 1994; Nazareth 2001; Nguyen 2018; Rich 1993; Rich 1995; Shaw 2000; Sulch 2000; Weinberger 1996), this was unclear for the remaining trials. We assessed 20 trials as having low risk of allocation concealment (Bonetti 2018; Farris 2014; Gillespie 2009; Goldman 2014; Harrison 2002; Jack 2009; Kennedy 1987; Kripalani 2012; Lainscak 2013; Legrain 2011; Naji 1999; Naughton 1994; Nazareth 2001; Nguyen 2018; Parfrey 1994; Preen 2005; Rich 1995; Shaw 2000; Sulch 2000; Weinberger 1996), this was unclear for the remaining trials. We assessed two trials to be at unclear risk for differences in baseline characteristics (Balaban 2008; Laramee 2003), and two as unclear for differences in outcome measures at baseline (Bolas 2004; Laramee 2003), the remaining trials were assessed as low risk of bias for these domains.

Blinding

We assessed 25 trials as low risk of bias for the measurement of the primary outcomes (readmission and length of stay), as investigators used routinely‐collected data to measure these outcomes (Balaban 2008; Bolas 2004; Cajanding 2017; Eggink 2010; Evans 1993; Gillespie 2009; Goldman 2014; Harrison 2002; Hendriksen 1990; Jack 2009; Kennedy 1987; Kripalani 2012; Lainscak 2013; Laramee 2003; Legrain 2011; Moher 1992; Naji 1999; Naughton 1994; Naylor 1994; Nazareth 2001; Parfrey 1994; Rich 1993; Rich 1995; Sulch 2000; Weinberger 1996); one trial as high risk of bias as outcome data were collected by interview rather than through routine data collection (Lindpaintner 2013) The remaining seven trials had an unclear risk of bias for this criterion.

Incomplete outcome data

Four trials were assessed as high risk of bias for incomplete outcome data, range between 19% to 33% (Bolas 2004; Bonetti 2018; Cajanding 2017; Nguyen 2018), three trials as unclear risk of bias (Hendriksen 1990; Naji 1999; Shaw 2000), and the remaining trials as low risk of bias.

Selective reporting

The funnel plots (Figure 3; Figure 4) for hospital length of stay and readmission reflect the small number of underpowered studies included in the review.

3.

Funnel plot of the effect of discharge planning on hospital length of stay

4.

Funnel plot of the effect of discharge planning on unscheduled readmission rates, outcome, average follow‐up within 3 months of discharge from hospital.

Other potential sources of bias

One study (Legrain 2011) used the Zelen patient preference method for randomisation, 380 individuals were randomised but not included in the study as they did not provide consent; and one study reported that after one year of recruitment, less than half of the required study sample was included and the study was terminated (Lisby 2019).

Fidelity of the intervention delivered.

A small number of studies reported difficulties with the implementation of discharge planning. In one trial the authors reported that the delivery of the intervention by two pharmacy case managers varied (Farris 2014), and Cajanding 2017 reported that 8/107 (7.5%) in the intervention group did not complete the intervention.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

Hospital length of stay

People admitted to hospital with a medical condition

There was a small reduction in the initial hospital length of stay for those allocated to discharge planning in trials that recruited older people following a medical admission (mean difference (MD) − 0.73 days, 95% confidence interval (CI) − 1.33 to − 0.12; I 2 9%; 11 trials, 2113 participants; moderate‐certainty evidence) (Analysis 1.1).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Effect of discharge planning on hospital length of stay, Outcome 1: Hospital length of stay ‐ older people with a medical condition

Following surgery

Discharge planning may lead to a small reduction in length of stay in participants who were recovering from surgery (mean difference (MD) ‐ 0.06/ a day, 95% CI − 1.23 to 1.11; I 2 0%; 2 trials, 184 participants; low‐certainty evidence) (Lin 2009; Naylor 1994) (Analysis 1.2).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Effect of discharge planning on hospital length of stay, Outcome 2: Hospital length of stay ‐ older people following surgery

Studies recruiting people with medical condition or recovering from surgery

Three studies recruited a mix of participants recovering from surgery and those with a medical condition, two reported a reduction of less than one day in the groups allocated to discharge planning (Evans 1993; Parfrey 1994) and one a reduction of just over three days (Hendriksen 1990) (Analysis 1.3) (low‐certainty evidence).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Effect of discharge planning on hospital length of stay, Outcome 3: Hospital length of stay ‐ studies recruiting people with a mix of conditions

| Hospital length of stay ‐ studies recruiting people with a mix of conditions | |

| Study | Heading 1 |

| Evans 1993 | Initial hospital length of stay T: Mean number of days in hospital 11.9 (SD 12.7) N=417 C: Mean number of days in hospital 12.5 (SD 13.5) N=418 |

| Hendriksen 1990 | Initial hospital length of stay T: 11 N=135 C: 14.3 N=138 |

| Parfrey 1994 | Recruited from two hospitals, reported a median difference for one hospital: − 0.80 days, P = 0.03; Intervention N=421; Control N=420 |

Readmission to hospital

People admitted to hospital with a medical condition

For older people with a medical condition, discharge planning led to a relative reduction in readmissions to hospital (average follow‐up within three months;risk ratio (RR) 0.89, 95% CI 0.81 to 0.97; 17 trials, I2 15%; 5126 participants; moderate‐certainty evidence).

People admitted to hospital for surgery

Two studies that recruited people recovering from surgery reported data on readmissions (low‐certainty evidence), one reported a 3% difference in readmission rates (95% CI − 7% to 13%; 134 participants) (Naylor 1994) and a second reported little or no difference (Lin 2009) (Analysis 2.2).

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Effect of discharge planning on unscheduled readmission rates, Outcome 2: Hospital readmission rates at various follow‐up times

| Hospital readmission rates at various follow‐up times | ||

| Study | Results | Notes |

| Participants with a medical condition | ||

| Bonetti 2018 | Mean hospital readmissions T= 4 (7.8) N=51, C= 7 (13.2) (N=53) |

Follow‐up: 30 days |

| Farris 2014 | At 30 d: T= 47/281 (17%), C = 43/294 (15%) Difference 2%; 95% CI − 0.04% to 0.08% At 90 d: T= 49/281 (17%), C = 47/294 (16%) Difference 1%; 95% CI − 5% to 8% |

— |

| Gillespie 2009 | At 12 months: T= 106/182 (58.2%), C = 110/186 (59.1%) Difference − 0.9%, 95% CI − 10.9% to 9.1% |

— |

| Goldman 2014 | At 30 d: T= 50/347 (14%), C = 47/351 (13%) Difference 1%; 95% CI − 4% to 6% At 90 d: I = 89/347 (26%), C = 77/351 (22%) Difference 3.7%; 95% CI − 2.6% to 10% |

Data provided by the trialists |

| Kennedy 1987 | At 1 week:

T= 2/38 (5%), C = 8/40 (20%)

Difference − 15%; 95% CI − 29% to − 0.4% At 8 weeks: I = 11/39 (28%), C = 14/40 (35%) Difference − 7%; 95% CI − 27.2% to 13.6% |

— |

| Lainscak 2013 | At 90 d: COPD− related T= 14/118 (12%), C = 33/135 (24%) Difference 12%; 95% CI 3% to 22% All‐cause readmission T = 25/118 (21%), C = 43/135 (32%) Difference 11%; 95% CI − 0.3% to 21% |

Data provided by the trialists; data also available for 30− and 180− d |

| Laramee 2003 | At 90 d:

T = 49/131 (37%), C = 46/125 (37%), P > 0.99 Readmission days: T= 6.9 (SD 6.5), C = 9.5 (SD 9.8) |

— |

| Lindpaintner 2013 | Similar readmission rate to hospital for both groups at 5 and 30 days | As reported by the authors; no further data reported T = 30, C = 30 |

| Lisby 2019 | At 30 d: T = 22/101 (22%), C = 19/99 (19%) Difference 3%; 95% CI ‐8.2% to 14.13 Total readmissions: T = 0.28 (SD 0.67); C = 0.26 (SD 0.63) |

Number of participants who were admitted at least once in each group Authors also report days to first readmission, and preventable first readmission Ascertained by chart review T = 101, C = 99 |

| Moher 1992 | At 2 weeks: T = 22/136 (16%), C = 18/131 (14%) Difference 2%; 95% CI − 6% to 11%, P = 0.58 | — |

| Naylor 1994 | Within 45‐90 d: T = 11/72 (15%), C = 11/70 (16%) Difference 1%; 95% CI − 8% to 12% | Authors also report readmission data for 2‐6 weeks follow up |

| Nazareth 2001 | At 90 d:

T = 64/164 (39%), C = 69/176 (39.2%)

Difference 0.18; 95% CI − 10.6% to 10.2% At 180 d: T = 38/136 (27.9%), C = 43/151 (28.4%) Difference 0.54; 95% CI − 11 to 9.9% |

— |

| Nguyen 2018 | Total number of participants readmitted T = 7/58 (12%), C = 6/68 (9%) Difference 3%, 95% CI ‐7.99 to 14.81 |

Follow‐up: 90 days |

| Weinberger 1996 | Number of readmissions per month

T = 0.19 (+ 0.4) (n = 695), C = 0.14 (+ 0.2), P = 0.005 (n = 701) At 6 months: T = 49%, C = 44%, P = 0.06 Treatment group readmitted 'sooner' (P = 0.07) |

Non‐parametric test used to calculate P values for monthly readmissions |

| Participants with medical or surgical condition | ||

| Evans 1993 | At 4 weeks:

T = 103/417 (24%), C = 147/418 (35%)

Difference − 10.5%; 95% CI − 16.6% to − 4.3%, P < 0.001 At 9 months: T = 229/417 (55%), C = 254/418 (61%) Difference − 5.8%; 95% CI −12.5% to 0.84%, P = 0.08 |

— |

| Participants recruited following surgery | ||

| Lin 2009 | Within 3 months: T=2/26 (7.7%), C=2/24 (8.3%) |

‐ |

| Naylor 1994 | Within 6 to 12 weeks: T = 7/68 (10%), C = 5/66 (7%) Difference 3%; 95% CI 7% to 13% | — |

| Participants with a mental health diagnosis | ||

| Naji 1999 | At 6 months: T = 33/168 (19.6%), C = 48/175 (27%) Difference 7.4%; 95% CI − 1.1% to 16.7% | Mean time to readmission T = 161 d, C = 153 d T: treatment; C: control; CI: confidence interval |

| Shaw 2000 | At 90 d: T = 5/51 (10%), C = 12/46 (26%) | |

People admitted to hospital with a mental health diagnosis

Two studies that recruited participants admitted to mental health facilities reported data on readmissions (low‐certainty evidence), one reported a difference of 7% (95% CI − 1% to 17%; 343 participants) (Naji 1999) and a second a reduction in readmission to hospital (T = 5/51 (10%), C = 12/46 (26%); 97 participants (Shaw 2000) (Analysis 2.2).

Studies recruiting people with medical condition or recovering from surgery

One trial (Evans 1993), reported a reduction in readmission rate to hospital for those receiving discharge planning (difference − 10.5%, 95% CI − 16.6% to − 4.3%) at four weeks follow‐up, but not at nine months (difference − 5.8%, 95% CI − 12.5% to 0.84%; P = 0.08; Analysis 2.2) (low ‐certainty evidence).

Patient health status

Mortality reported in studies that recruited people admitted to hospital with a medical condition

For older people with a medical condition (usually heart failure) it is uncertain if discharge planning has an effect on mortality at three‐ to nine‐month follow‐up (RR 1.05, 95% CI 0.85 to 1.29; I 2 0%; ; 8 trials, 2721 participants; moderate‐certainty evidence) (Analysis 3.1); (Goldman 2014; Lainscak 2013; Laramee 2003; Legrain 2011; Nazareth 2001; Nguyen 2018; Rich 1995; Sulch 2000).

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3: Effect of discharge planning on health status, Outcome 1: Mortality at 3 to 9 months

Mortality reported in studies that recruited people with medical condition or recovering from surgery

One study reported data for mortality at nine‐month follow‐up (treatment: 66/417 (15.8%), control: 67/418 (16%) (low‐certainty evidence) (Evans 1993) Analysis 3.2).

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3: Effect of discharge planning on health status, Outcome 2: Mortality for trials recruiting participants with a medical condition and those recovering from surgery

| Mortality for trials recruiting participants with a medical condition and those recovering from surgery | ||

| Study | Mortality at 9 months | Notes |

| Evans 1993 | T = 66/417 (16%) C = 67/418 (16%) | — |

Health status and quality of life reported in studies that recruited people admitted to hospital with a medical condition

We are uncertain whether discharge planning improves patient reported health status or quality of life (12 studies, 2927 participants when reported; low‐certainty evidence) due to variability among the trials and the range of measures used to assess health status (Harrison 2002; Kennedy 1987 Preen 2005; Weinberger 1996; Sulch 2000; Lainscak 2013; Lindpaintner 2013; Nguyen 2018; Lisby 2019; Nazareth 2001; Cajanding 2017; Rich 1995) (Analysis 3.3).

3.3. Analysis.

Comparison 3: Effect of discharge planning on health status, Outcome 3: Patient‐reported outcomes: a medical condition

| Patient‐reported outcomes: a medical condition | ||

| Study | Patient health outcomes | Notes |

| Patients with a medical condition | ||

| Cajanding 2017 |

MLHFQ Mean difference (C ‐ T) 8.59 (SD 2.29), 95% CI 4.02 to 13.16 CSE Mean difference (C ‐ T) ‐5.61 (SD 1.13), 95% CI ‐7.87 to ‐3.36 |

Minnesota Living With Heart Failure Questionnaire (MLHFQ): a lower score indicates less disability from symptoms Cardiac Self‐Efficacy Questionnaire (CSE): higher scores represent higher self‐confidence Follow‐up: 30 days As reported by the authors, mean difference at follow‐up T = 75, C = 68 C: control; T: treatment; SD: standard deviation |

| Harrison 2002 |

SF‐36 Baseline Physical component T = 28.63 (SD 9.46) N = 78 C = 28.35 (SD 9.11) N = 78 Mental component T = 50.49 (SD 12.45) N = 78 C = 49.81 (SD 11.36) N = 78 At 12 weeks Physical component T = 32.05 (SD 11.81) N = 77 C = 28.31 (SD 10.0) N = 74 Mental component T = 53.94 (SD 12.32) N = 78 C = 51.03 (SD 11.51) N = 78 MLHFQ At 12 week follow‐up (See table 4) n, % Worse: T = 6/79 (8), C = 22/76 (29) Same: T = 7/79 (9), C = 10/76 (13) Better: T = 65/79 (83), C = 44/76 (58) |

SF‐36 a higher score indicates better health status MLHFQ: a lower score indicates less disability from symptoms T = 79, C = 76 (at 12 week follow‐up) |

| Kennedy 1987 | Long Term Care Information System (LTCIS) Health and functional status (also measures services required) | No data reported T = 39, C = 41 |

| Lainscak 2013 |

St. George’s Respiratory

Questionnaire (SGRQ) Change in score from 7 to 180 days after discharge T = 1.06 (IQR CI 8.43 to − 9.50), C = − 0.11 (IQR 8.12 to − 11.34) |

Complete data available for approximately half of the participants allocated to the intervention and comparison groups For the SGRQ, higher scores indicate more limitations; minimal clinically important difference estimated as 4 points. T = 63, C = 72 |

| Lisby 2019 |

VAS T = 60.4 (95% CI 55.4 to 65.5), N = 76; C = 60.2 (95% CI 55.1 to 65.4), N = 81. P = 0.96 |

Visual Analogue Scale (0‐100, higher scores represent better perceived health) Mean scores at 30 days post‐discharge; authors also report EQ‐5D scores for each item T = 76, C = 81 |

| Naylor 1994 | Data aggregated for both groups. Mean Enforced Social Dependency Scale increased from 19.6 to 26.3 P < 0.01 | Decline in functional status reported for all patients. Scale measured:

T = 72, C = 70 |

| Nazareth 2001 |

General well‐being questionnaire: 1 = ill health, 5 = good health

At 3 months:

T = 76, mean 2.4 (SD 0.7)

C = 73, mean 2.4 (SD 0.6) At 6 months: T = 62, mean 2.5 (SD 0.6) C = 61, mean 2.4 (SD 0.7) Mean difference 0.10; 95% CI − 0.14 to 0.34 |

T = 62, C = 61 (at 6 months follow‐up) |

| Nguyen 2018 | EQ‐5D‐3L T = median 0.000 (IQR 0.000 to 0.275), C = 0.234 (IQR 0.000 to 0.379) |

European Quality of Life Questionnaire – (EQ‐5D‐3L). Dimensions: mobility, self‐care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, and anxiety/depression. Each dimension has 3 levels: no problem, some problems, and extreme problems IQR: Interquartile range T = 79, C = 87 Follow‐up: 90 days Changes in quality of life from baseline at the first 3 months after discharge. Data as reported by the authors, no additional data available |

| Preen 2005 | SF‐12 Mental component score Predischarge score: T = 37.4 SD 5.4 C = 39.8 SD 6.1 7 d postdischarge: T = 42.4 SD 5.6 C = 40.9 SD 5.7 Physical component score Predischarge score: T = 27.8 SD 4.8 C = 28.3 SD 4.7 7 d postdischarge: T = 27.2 SD 4.5 C = 27.2 SD 4.1 |

Baseline N: T 91 C 98 Number at follow‐up not reported. |

| Rich 1995 |