Abstract

Inorganic ions are essential factors stabilizing nucleosome structure; however, many aspects of their effects on DNA transactions in chromatin remain unknown. Here, differential effects of K+ and Na+ on the nucleosome structure, stability, and interactions with protein complex FACT (FAcilitates Chromatin Transcription), poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase 1, and RNA polymerase II were studied using primarily single-particle Förster resonance energy transfer microscopy. The maximal stabilizing effect of K+ on a nucleosome structure was observed at ca. 80–150 mM, and it decreased slightly at 40 mM and considerably at >300 mM. The stabilizing effect of Na+ is noticeably lower than that of K+ and progressively decreases at ion concentrations higher than 40 mM. At 150 mM, Na+ ions support more efficient reorganization of nucleosome structure by poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase 1 and ATP-independent uncoiling of nucleosomal DNA by FACT as compared with K+ ions. In contrast, transcription through a nucleosome is nearly insensitive to K+ or Na+ environment. Taken together, the data indicate that K+ environment is more preserving for chromatin structure during various nucleosome transactions than Na+ environment.

Keywords: FACT, nucleosome, poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase 1, potassium ion, RNA polymerase II, sodium ion, structure

Introduction

Nucleosomes provide the first level of DNA compaction in chromatin and mediate regulated access of chromatin processing proteins to DNA (Klemm et al., 2019; Prieto & Maeshima, 2019). Stable nucleosome structure is maintained by the wrapping of polyanionic double-stranded DNA over cationic histone octamer surface and by the screening of uncompensated charges with inorganic ions (Materese et al., 2009). Inorganic ions have several essential functions: a reduction of electrostatic repulsion between cationic histones forming histone octamer, a decrease of repulsion between neighboring negatively charged DNA gyres on the octamer surface, assistance in strong bending of nucleosomal DNA, and assistance in the regulation of DNA-histone interactions during structural rearrangements of nucleosomes (Materese et al., 2009; Carrivain et al., 2012; Onufriev & Schiessel, 2019). Moreover, at physiological concentrations, the ions can promote further folding of certain nucleosomal arrays into more compact higher-order chromatin structures even in the absence of linker histones that are typically responsible for the formation and stabilization of compact chromatin (Allahverdi et al., 2015).

Low concentration of ions, for example, 10 mМ NaCl, is sufficient for long-term preservation of nucleosome structure in vitro (Gaykalova et al., 2009), while physiologically relevant concentrations of ions are an order of magnitude higher and presumably can affect the structure and stability of nucleosomes, as well as their interactions with DNA repair and replication proteins, and with transcription machinery. Although this field is a subject of numerous studies (Gansen et al., 2013; Allahverdi et al., 2015; Hazan et al., 2015; Lyubitelev et al., 2017), many aspects of inorganic ion action in nucleosome function remain unknown.

Biochemical studies of DNA and nucleosomes are often performed in Na+ environment, although potassium ions are predominant inside the cell nuclei. In some cases, it was reported that K+ and Na+ produce similar effects on DNA and chromatin (Braunlin & Nordenskiöld, 1984; Korolev et al., 1999a, 1999b; Korolev & Nordenskiöld, 2000), but other observations show that K+ and Na+ are considerably different in their interactions with DNA (Zinchenko & Yoshikawa, 2005; Hibino et al., 2006) and nucleosomes (Allahverdi et al., 2015; Lyubitelev et al., 2017).

In the present work, we investigate the differential effects of K+ and Na+ ions on the structure of a nucleosome and its stability, as well as on transcription of nucleosomal DNA by RNA polymerase II (Pol II) and interactions of nucleosomes with poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase 1 (PARP1) and protein complex FACT (FAcilitates Chromatin Transcription).

Materials and Methods

Nucleosomes

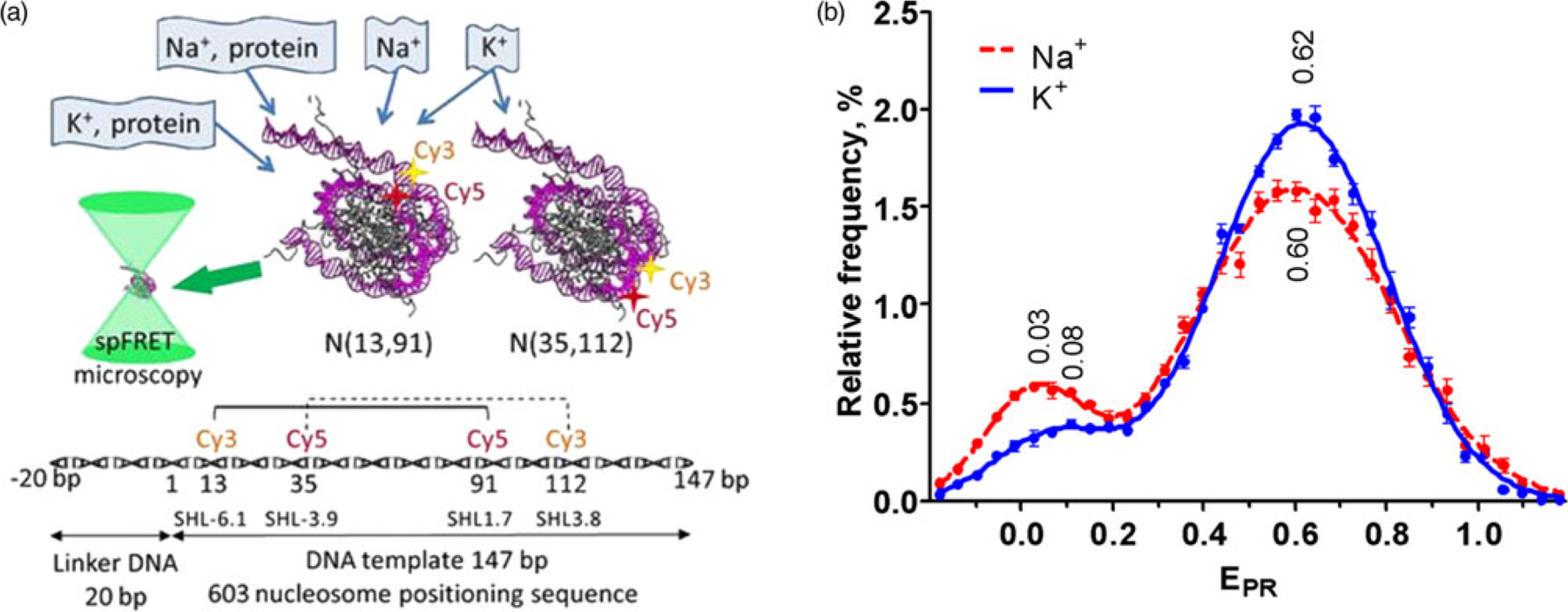

Fluorescently labeled nucleosomes were assembled on a short dsDNA template (167 bp) containing a 20-bp linker DNA fragment followed by the strong nucleosome positioning 603 sequence (147 bp) (Lowary & Widom, 1998). Nucleosomes N(13,91) and N(35,112) were formed using two DNA templates containing Cy3 and Cy5 labels at positions 13 and 91 bp or 35 and 112 bp from the linker-proximal boundary of the 603 sequence, respectively (Fig. 1a). A full sequence of the dsDNA template was as follows:

Fig. 1.

Analysis of nucleosome structure in the presence of K+ or Na+ ions. (a). The experimental approach used to study nucleosome structure and interactions with nuclear proteins in K+ or Na+ environment. Mononucleosomes that were fluorescently labeled either near the entrance of DNA into a nucleosome, i.e. N(13,91), or in a region distal to the entrance, i.e. N(35,112), as well as their complexes with nuclear proteins were studied using spFRET microscopy in a freely diffusion regime. Positions of the labels attached to neighboring DNA gyres are indicated with asterisks. A schematic diagram of the DNA template and relative positions of the labels are shown below. (b). EPR profiles of nucleosomes N(13,91) in a buffer containing either 150 mM KCl (blue) or 150 mM NaCl (red) were calculated using data of spFRET-microscopy. The profiles were averaged over 5 independent experiments (mean ± SEM) and fitted with two Gaussians. Positions of Gaussian maxima are indicated.

5′-CAAGCGACACCGGCACTGGGCCCGGTTCGCGCT#-Cy3CC

3′-GTTCGCTGTGGCCGTGACCCGGGCCAAGCGCGAGG

CGCCTTCCGTGTGTT GTCGT*-Cy5CTCTCGGGCGTCTAAG

GCGGAAGGCACACAACAGCAGAGAGCCCGCAGATTC

TACGCTTAGCGCACG GTAGAGCGCAATCCAAGGCTAAC

ATGCGAATCGCGTGCCATCTCGCGTTAGGTTCCGATTG

CACCGTGCATCGATGTTGAAAGAGGCCCTC

GT#-Cy5GGCACGTAGCTACAACTTTCT*-Cy3CCGGGAG

CGTCCTTATTACTTCAAGTCCCTGGGGT-3′

GCAGGAATAATGAAGTTCAGGGACCCCA-5′

A linker region of DNA is shown in italic; the 603 sequence is underlined. Positions of nucleotides labeled with Cy3 and Cy5 fluorophores are in bold. T# and T* are nucleotides that were labeled in the DNA template prepared for N(13,91) and N (35,112) nucleosomes, respectively.

Nucleosomes for transcription by Pol II assay were assembled on 227-bp DNA template (a 80-bp linker followed by the 147-bp 603 sequence) containing TspRI site. A full sequence of the DNA template was as follows:

ggcactgggCGAGACTACACGAATAGGCGTTTTCCTAGTACAAATCACCCCAGCGTGAGCCGTAAAATAATCGACACTCTCGGGTGCCCAGTTCGCGCGCCCACCTACCGTGTGAAGTCGTCACTCGGGCTTCTAAGTACGCTTAGCGCACGGTAGAGCGCAATCCAAGGCTAACCACCGTGCATCGATGTTGAAAGAGGCCCTCCGTCCTTATTACTTCAAGTCCCTGGGGT

A linker region of DNA is shown in italic, while the 603 sequence is underlined. The TspRI site is shown in the lower case. The templates were obtained by polymerase chain reaction using primers described previously (Bondarenko et al., 2006; Valieva et al., 2016) and purified as described (Kudryashova et al., 2015). Nucleosomes were assembled on the DNA templates using the H1 histone-free donor chromatin from chicken erythrocytes by dialysis from 2M NaCl (Gaykalova et al., 2009). Purified nucleosomes were stored in the buffer containing 10 mM NaCl, 10 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 0.1% NP40, 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol, and 0.2 mM EDTA.

Studies of Na+ and K+ Effects on the Nucleosome Structure

For single-particle Förster resonance energy transfer (spFRET) microscopy studies, nucleosomes were diluted to ca. concentration 1 nM with a buffer containing a variable concentration of NaCl or KCl. Beside the variable ion component, the buffer contained 0.1 mM NaCl, 0.001% NP40, 0.5 mM EDTA, 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), and 2 mM β-mercaptoethanol.

spFRET microscopy was conducted in a free diffusion regime in a well of the 12-well silicon chamber (Greiner Bio-One, Germany) attached to a cover glass. spFRET microscopy measurements were carried out with the LSM710-Confocor3 system (Carl Zeiss, Germany) using the C-Apochromat objective (40×, NA1.2) as described (Kudryashova et al., 2015). Fluorescence was excited with the 514.5 nm wavelength and registered with avalanche photodiodes in the 530–635 nm (Cy3) and 635–800 nm (Cy5) spectral ranges. Signals from single nucleosomes were recorded during several consecutive periods of 10 min immediately after dilution of nucleosomes with a buffer.

Data collected during particular time periods were treated separately and presented as relative frequency distributions of nucleosomes by a proximity ratio (EPR) with a bin width of 0.04 as described (Kudryashova et al., 2015). EPR is the FRET efficiency without correction for quantum yields and detection sensitivity of fluorophores.

EPR distributions of nucleosomes (EPR profiles) were further approximated as a superposition of two or three Gaussian curves, where each Gaussian corresponded to a subpopulation of nucleosomes having a particular structure. Initially, maxima and widths of Gaussians for the description of LF and HF subpopulations of nucleosomes were determined from EPR profiles measured at different concentrations of KCl or NaCl and averaged separately. Positions of peak maxima are presented in the text as mean ± SEM. The averaged values of peak widths and maximum positions were then used to fit the EPR profiles with Gaussian curves (Supplementary Figs. S1, S2). The third Gaussian curve was introduced to fit EPR profiles when the considerable deviation of the profile (calculated with two Gaussians) from the experimental data was observed in the MF region, and the goodness of fit R2 decreased from >0.96 to <0.91. The goodness of fit R2 for all the profiles presented below is >0.96. A relative size (content) of each nucleosome subpopulation was calculated as a ratio of area under corresponding Gaussian peak to the area under the entire EPR profile.

Contents of different nucleosome subpopulations (SC) were plotted as a function of time (t) after dilution of nucleosomes with a buffer containing a particular concentration of K+ or Na+ ions and fitted with an equation

| (1) |

where SC0 is the subpopulation content immediately after dilution of nucleosomes with a buffer and R is a rate of SC changes (a rate of time-dependent DNA uncoiling).

Presented results were reproduced in several independent experiments. Sampling sizes were 4,000–8,000 nucleosomes per 10 min measurement.

Experiments with FACT

Yeast FACT and Nhp6 were purified as described (Ruone et al., 2003; Biswas et al., 2005) and kindly provided by Prof. T. Formoza. All the measurements with FACT were performed in a solution containing 7 mM HEPES (pH 8.0), 0.1 mM EDTA, 3 mM Tris-HCl, 0.3% glycerol, 3.2% sucrose, 53 mg/L BSA, 5 mM β-ME, 115 mM KCl (or NaCl), and supplemented (or not) with 2 mM MgCl2.

Complexes of N(13,91) nucleosomes (ca. 0.5 nM) with FACT/Nhp6 (C1 = (33 nM Spt16/Pob3, 0.33 μM Nhp6) or C2 = (67 nM Spt16/Pob3, 0.67 μM Nhp6)) or with FACT (33 or 67 nM Spt16/Pob3) were prepared as described earlier (Valieva et al., 2016). Three independent series of experiments were performed, and the data (calculated EPR distributions of nucleosomes and their complexes with FACT) were averaged.

Experiments with PARP1

Human recombinant PARP1 (gift of Prof. J. M. Pascal) was purified as described (Langelier et al., 2017). Nucleosomes (ca. 1 nM) were mixed with 50 nM PARP1 in a solution containing 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.9), 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM β-ME, and 150 mM NaCl (or KCl), incubated in low-adhesion tubes for 30 min at 25°C, and analyzed by spFRET microscopy. Calculated EPR profiles were averaged over three independent experiments, and the data were presented as mean ± SEM.

In Vitro Transcription Assay

Yeast Pol II was purified as described (Kulaeva et al., 2009). The in vitro transcription assay with Pol II was performed as described (Kulaeva et al., 2009; Gaykalova et al., 2012). In short, the elongation complexes (ECs) were assembled using purified yeast Pol II as follows. Template oligonucleotide and 9-nt RNA primer were incubated with Pol II to form RNA:DNA duplex with Pol II. ECs were then formed by adding an excess of non-template DNA oligonucleotide (the design of oligonucleotides allows the formation of TspR1 site after annealing). These ECs were purified with Ni-NTA resin (Qiagen) using His-tag on Pol II and ligated to the nucleosomal template through the TspR1 site by T4 ligase (Promega). Pol II was then progressed to position 83 bp upstream the promoter-proximal boundary of the 603 nucleosome using unlabeled ATP, CTP, and α−32P-labeled GTP. Then transcription was resumed in the presence of all unlabeled NTPs (0.5 mM) in the transcription buffer containing different concentrations of NaCl or KCl for 10 min. Transcription was terminated using phenol/chloroform extraction. RNA transcripts were purified and analyzed by denaturing PAGE.

Results and Discussion

Effects of K+ and Na+ on the Structure of the Ends of Nucleosomal DNA

Nucleosomes N(13,91) were studied by spFRET microscopy in the buffer containing either 150 mM NaCl or 150 mM KCl to examine the possible influence of the type of monovalent cations on the nucleosome structure near the entrance of DNA into a nucleosome core at physiological conditions. Two subpopulations of N(13,91) were observed in each case (Fig. 1b; Supplementary Fig. S1a): (1) the main high-FRET (HF) subpopulations detected as peaks in the EPR profiles centered at 0.60 ± 0.01 or 0.62 ± 0.01 (Na+ or K+ environment, respectively); (2) the minor low-FRET (LF) subpopulations centered at 0.03 ± 0.01 or 0.08 ± 0.01, respectively. HF subpopulation includes nucleosomes with DNA tightly wrapped over a histone octamer when the neighboring DNA gyres containing the labeled sites (13 and 91 bp) are close to each other (Fig. 1a). LF subpopulation comprises nucleosomes with disturbed packing of nucleosomal DNA that occurred due to so-called nucleosome breathing (spontaneously reversible uncoiling of DNA (10–20 bp) from histone octamer near the boundaries of a nucleosome core) (Buning & Van Noort, 2010) and histone-free DNA released in the course of nucleosome dissociation at the low nucleosome concentration (ca. 1 nM at spFRET measurements) (Hazan et al., 2015). EPR distributions of N(13,91) are considerably different in Na+ versus K+ environments, including the differences in dispersions of the HF normal distribution, relative sizes of LF and HF subpopulations, and positions of the LF maxima.

Dispersions characterized by the widths at the half maxima of the HF normal distributions are 0.370 ± 0.006 and 0.430 ± 0.006 for N(13,91) in K+ and Na+ environments, respectively. This difference can indicate that K+ ions promote a tighter association of nucleosomal DNA with histones, possibly restricting the mutual movement of neighboring DNA gyres as compared to Na+ environment. At the same time, a type of monovalent cations does not affect the packing of nucleosomal DNA of N(13,91), since maxima of the HF normal distributions are nearly the same in K+ and Na+ environments (Fig. 1b). LF subpopulation of N(13,91) increases from 11 ± 1% in the K+ buffer to 19.4 ± 0.5% in the Na+ buffer, and this effect is statistically reliable ( p = 0.001). It means that K+ ions reduce the probability of spontaneous DNA uncoiling as compared to Na+. Moreover, the amplitude of “nucleosome breathing” is decreased in K+ environment, since the value of the LF peak maximum is higher in the Na+ buffer: 0.08 versus 0.03.

Comparative PAGE analysis of N(13,91) nucleosomes pre-incubated at 150 mM NaCl or KCl shows Na+-facilitated release of a small amount of DNA and absence of detectable free DNA at 150 mM KCl (Supplementary Fig. S3) that is consistent with the data of spFRET microscopy about the stabilizing effect of K+ on a nucleosome structure.

Molecular dynamics simulations revealed that Na+ ions have an enhanced ability to penetrate DNA interior and condense around DNA as compared to K+ ions due to a complex combination of electrostatic, steric, and hydration effects (Savelyev & Papoian, 2006). Na+ ions have higher activity toward DNA than K+ ions in a crowded environment (Zinchenko & Yoshikawa, 2005). It means that Na+ ions can compete with histones for interactions with DNA more efficiently than K+ ions, in particular, in the regions of DNA entry into nucleosome. This can explain the observed shift of dynamics of “nucleosome breathing” toward the local DNA uncoiling in the presence of Na+ ions and release of DNA in some cases. The predicted decrease in the flexibility of DNA in the presence of Na+ ions (Savelyev & Papoian, 2006) seems to be an additional factor promoting spontaneous DNA uncoiling. Similarly, wrapped DNA can be more dynamic because of enhanced interfering of Na+ ions with DNA-histone bonds, and it is detected as an increased dispersion of the HF normal distribution in the Na+-containing buffer.

Concentration Dependence of the Effects of K+ and Na+ on the Nucleosome Structure

To further characterize the structural features of nucleosomes in K+ and Na+ environments, the spFRET studies were carried out at concentrations of monovalent cations ranging from 0.1 to 500 mM. A comparison of the effects of K+ and Na+ on the nucleosome structure at different ion concentrations was performed by measuring the EPR distributions of N(13,91) during five consecutive 10-min intervals after changing ion composition (Fig. 2). The EPR profiles were fitted as a superposition of Gaussian curves (normal distributions) corresponding to subpopulations of N (13,91) with different structures, and relative contents of these subpopulations were quantified. Dependences of subpopulation contents on time (Fig. 3) were approximated with a linear function according to equation (1) (see Materials and Methods), and two parameters were defined: the content of HF subpopulation immediately after changing ion composition (SC0(HF), Fig. 4a) and the rate of DNA uncoiling (−R(HF), Fig. 4b). The analysis of the data shows that nucleosome structure changes as a function of ion concentration and time, and these changes depend on the type of cations present in a solution.

Fig. 2.

Stability of nucleosomes N(13,91) as a function of time at different concentrations of Na+ (a,b,d,f,h,j) and K+ (c,e,g,i,k) ions. spFRET-microscopy analysis: typical EPR profiles of N(13,91) are presented at different time intervals after ion addition.

Fig. 3.

Time-courses of nucleosomal DNA uncoiling at different concentrations of K+ and Na+ ions. spFRET-microscopy analysis: сhanges in the content of HF (solid symbols and lines) and MF (open symbols and dashed lines) subpopulations of N(13,91) (all symbols except for triangles) and N(35,112) (light green triangles) are presented as a function of time after addition of K+ (dark or light green) and Na+ (circles, magenta) ions. Experimental data (symbols) were fitted with linear dependences (lines). Concentrations of the cations (mM): 0.1 (a), 40 (b), 80 (c), 150 (d), 300 (e), 500 (f), 700 (g), 1,000 (h), and 1,300 (i).

Fig. 4.

Uncoiling of nucleosomal DNA at different ion concentrations. (a,b) Dependences of parameters SC0(HF) and –R(HF) defined by equation (1) on Na+ and K+ concentrations. SC0(HF) is a content of HF subpopulation immediately after dilution of nucleosomes N(13,91) with a buffer. Asterisks mark significantly different values ( p < 0.05). Parameter −R(HF) is a rate of changes in the HF subpopulation content (a rate of time-dependent DNA uncoiling) for N(13,91). (c) Time dependences of the ratio (α) of disordered nucleosomes N(35,112) (LF and MF subpopulations) to disordered nucleosomes N(13,91). Ratio α shows how many nucleosomes are subjected to increased uncoiling among all nucleosomes with disordered structure.

At the conditions of spFRET measurements, some nucleosomes can lose their initial structure with time (Hazan et al., 2015). Several reasons can provoke structural rearrangement and/or disruption of nucleosomes: (i) adsorption of histones on the glass/silicon chamber walls occurring during collisions of nucleosomes with the walls; (ii) spontaneous dissociation of histones, which is practically irreversible at the nanomolar concentration of nucleosomes used in the spFRET experiments; (iii) reversible partial unfolding of nucleosomes without loss of histones (Böhm et al., 2011). The probability of these events depends on the stability of the nucleosome structure, which is apparently modulated by ionic strength and a type of cations present in a solution (Figs. 2, 3).

Time-dependent structural changes were observed as an increase in the LF subpopulation with a concomitant decrease in the HF subpopulation. At 300 and 500 mM NaCl or KCl, these changes were accompanied by the appearance of the middle-FRET (MF) subpopulation of N(13,91) nucleosomes (Fig. 3), which was recognized in the course of fitting of EPR profiles with Gaussian curves as an additional normal distribution centered at EPR = 0.47 (Supplementary Fig. S1b). The MF subpopulation having a moderately disturbed structure of nucleosomal DNA could comprise of nucleosomes, where H2A–H2B histone dimer is partially separated from (H3–H4)2 tetramer, but all histones are still bound to DNA (Böhm et al., 2011). The formation of such an intermediate state was revealed for nucleosomes assembled on the 601 DNA template at NaCl concentrations of >300 mM (Böhm et al., 2011). Native PAGE analysis shows that migration of N(13,91) nucleosomes pre-incubated with 500 mM NaCl or KCl occurs slower than those pre-incubated with 150 mM NaCl or KCl, while according to FRET-in-gel analysis, a distance between DNA gyres near the labels is not considerably disturbed (Supplementary Fig. S3). These observations are in a general agreement with the formation of the intermediate conformational state (proposed above) that slightly increases the effective hydrodynamic diameter of nucleosomes and decreases the rate of their migration in the gel. According to the PAGE analysis, the amount of free DNA released from the nucleosomes at 500 mM NaCl or KCl is slightly higher than at 150 mM NaCl, and Na+ promotes greater DNA release as compared to K+ (Supplementary Fig. S3).

The estimated parameter SC0(HF) (content of fully coiled HF nucleosomes) reflects alterations in a nucleosome structure that occur immediately after changing ion composition. SC0(HF) increased slightly when the KCl concentration raised from 40 to 80–150 mM and decreased at 300–500 mM KCl (Fig. 4a). In contrast, SC0(HF) decreased steadily when NaCl concentration raised from 40 to 300 mM (Fig. 4a). Interestingly, SC0(HF) was not significantly changed when a concentration of either KCl or NaCl increased from 300 to 500 mM. Since K+ provided higher SC0(HF) values than Na+ in the entire range of studied concentrations except for 40 mM (Fig. 4a), the potency of K+ to uncoil nucleosomal DNA is generally lower than that of Na+. At 80–150 mM K+ (i.e., at physiological concentrations), the probability of DNA uncoiling from a nucleosome (“nucleosome breathing”) is minimal. In the case of Na+, the probability of nucleosomal DNA uncoiling is minimal at the ion concentration of 40 mM or less.

It seems that the effects related to differential interaction of Na+ and K+ ions with DNA (Zinchenko & Yoshikawa, 2005; Savelyev & Papoian, 2006) increase in the 80–300 mM range of ion concentrations, while at higher concentration, a general destabilizing influence of high ionic strength begins to obscure these differences (Fig. 4a). A higher flexibility of DNA in the presence of K+ ions (Savelyev & Papoian, 2006) could also contribute to the enhanced stability of the nucleosome structure at physiological concentrations of ions.

Initial alterations in the distribution of N(13,91) between LF and HF states induced by the changes in ionic strength are followed by a time-dependent decrease in HF subpopulation (Figs. 2, 3) that is characterized by the rate of DNA uncoiling (−R (HF), Fig. 4b). In K+ environment, this rate is lower (<0.07% of nucleosomes per minute) at 40–150 mM KCl and increases nearly linearly with a further increase in ionic strength (Fig. 4b). Except for the 150 mM concentration, the rate of DNA uncoiling is slightly higher in Na+ than in K+ solutions, but this difference is statistically insignificant (Fig. 4b).

Life-times of the DNA in the partially uncoiled and coiled states during the nucleosome breathing are 10–50 ms and 0.25–1.2 s, respectively (Buning & Van Noort, 2010). Therefore, local structural alterations related to “nucleosome breathing” have to be equilibrated during the short period after changes in ion composition, and the observed long-term structural rearrangements are mainly associated with further increased uncoiling of nucleosomal DNA.

The data indicate that, as compared to Na+ ions, K+ cations stabilize nucleosome structure, reduce the probability and amplitude of “nucleosome breathing” at physiological ion concentration, and cause less pronounced disruption of the nucleosome structure when ion concentration deviates from the physiological one. Our observation of nucleosome structure stabilization by K+ ions is consistent with data on stabilizing effect of K+ over Na+ on a structure of DNA duplex revealed with an optical tweezing technique (Vieregg et al., 2007).

K+-Induced Rearrangements in the Structure of Nucleosomal DNA

Since K+ is predominant in the cell nucleus, and the structural features of nucleosomes in K+ environment are still insufficiently studied, we utilized N(35,112) to probe structural rearrangements induced by K+ in the region that is localized more distally from the entrance/exit of DNA into/from the nucleosome. At the physiological conditions (150 mM KCl), the structure of nucleosomal DNA at the distal region (at 35 and 112 bp) is nearly uniform: a distance between neighboring DNA gyres is fixed, and the majority of nucleosomes (95 ± 1%) belongs to an HF subpopulation presented in the EPR histogram by a normal distribution centered at 0.60 ± 0.01 (Fig. 5; Supplementary Fig. S2a). Small LF subpopulation (normal distribution centered at 0.03 ± 0.01, Fig. 5) is likely produced primarily by histone-free DNA, since structural changes induced by “nucleosome breathing” cannot spread so deep into the nucleosome.

Fig. 5.

Stabilities of N(35,112) (a–f) and N(13,91) (g–i) nucleosomes at different concentrations (0.15–1.3M) of K+ ions. spFRET-microscopy analysis: typical EPR profiles of N(35,112) and N(13,91) are presented at different time intervals after ion addition.

An increase in KCl concentration from 0.5 to 1M results in a decrease in HF subpopulation and concomitant increase in LF subpopulation of N(35,112) nucleosomes (Figs. 5c–5e). Noticeable time-dependent structural changes in this region of nucleosomal DNA are detected at 500 mM KCl and higher, while immediate alterations in the structure of this region are observed when KCl concentration is >1M (Fig. 5f). When KCl concentration is ≥1M, a small MF subpopulation of nucleosomes (normal distribution centered at EPR = 0.37 ± 0.04; Supplementary Fig. S2b) is observed in addition to HF and LF subpopulations (Figs. 3h, 3i). Structural changes in the distal region indicate increased uncoiling of nucleosomal DNA. A comparison of data for N(13,91) and N(35,112) (Figs. 2, 3, 5) shows that the increase in the concentration of K+ in the 0.5–1.3M range results in progressive uncoiling of nucleosomal DNA that begins at the ends of nucleosomal DNA and spreads into the nucleosome in a time-dependent manner. This conclusion is illustrated in Figure 4c showing time dependences of the ratio (α) of disordered nucleosomes N(35, 112) (LF and MF subpopulations) to disordered nucleosomes N(13,91) at 500–1,300 mM KCl. At 300 mM KCl, the structure disturbance is local and occurs near the entrance of DNA into nucleosome (Figs. 2, 3, 5). At 500 and 700 mM KCl, the structural changes are mainly local: α is less than 20% during 40 min of exposure to KCl (Fig. 4c). At 1M KCl, all nucleosomes have the disturbed structure, and the progressive DNA uncoiling occurs in 40–80% of nucleosomes as a function of time (Fig. 4с). At 1.3M KCl, the increased DNA uncoiling is observed in the majority of nucleosomes (Fig. 4с). Our previous studies show that the structural changes occurring in nucleosomes during short (10 min) exposure to 700 mM KCl are fully reversible (Feofanov et al., 2018). Therefore, at KCl concentration of less than 700 mM, most of the observed structural changes are restricted by DNA uncoiling from histone octamer, which involves from 13 to 35 bp of nucleosome positioning sequence, and proceed without loss of core histones.

Only 70 and 50% of nucleosomes restore their initial structure after the short exposure to 1.0 and 1.3M KCl, respectively (Feofanov et al., 2018). At these concentrations, DNA uncoiling involves more than 35 bp and results in the dissociation of core histones, which is essentially irreversible at low (ca. 1 nM) concentration of nucleosomes. PAGE analysis shows that pre-incubation with 1.0 or 1.3M KCl leads to the release of DNA in a noticeable fraction of nucleosomes, while the remaining nucleosomes have an altered mobility in the gel (especially at 1.3M KCl) as compared to the nucleosomes at 150 mM KCl (Supplementary Fig. S3). In general agreement with the spFRET data, the nucleosomes pre-incubated with 1.3M KCl demonstrate reduced FRET in gel as follows from the observed red-to-yellow change of color in the nucleosome band (Supplementary Fig. S3). The altered mobility of these nucleosomes and the decrease in FRET likely indicate that partial dissociation of core histones occurs before or during electrophoresis.

Since K+ and Na+ differentially affect the nucleosome structure, next we have studied the effects of these cations on interactions of FACT, PARP1, and Pol II with nucleosomes.

Effect of Cations on FACT-Induced Nucleosome Unfolding

Yeast FACT is a histone chaperone that induces ATP-independent and reversible uncoiling of nucleosomal DNA (Valieva et al., 2016). Yeast FACT is a complex of Spt16 and Pob3 proteins functioning in the presence of Nhp6 protein. We have analyzed differences in (FACT/Nhp6)-nucleosome interactions in K+- and Na+-containing solutions (Fig. 6a). Two concentrations of FACT/Nhp6 were selected, which induced DNA uncoiling in 50–80% of nucleosomes. This uncoiling occurred only when both FACT and Nhp6 were present in a solution (Supplementary Fig. S4a), and it was accompanied by an increase in an amplitude of the low-EPR peak and a decrease in an amplitude of the high-EPR peak (Supplementary Fig. S4a). (FACT/Nhp6)-mediated nucleosomal DNA uncoiling involved a higher fraction of nucleosomes in Na+ than in K+ environment (Supplementary Fig. S4). The differences were 11 ± 2 and 8 ± 3% of unfolded nucleosomes at the C1 and C2 concentrations of FACT/Nhp6, respectively. Moreover, the differential effect of Na+ and K+ on the interaction of FACT/Nhp6 with a nucleosome is preserved in the presence of 2 mM Mg2+ ions (Fig. 6a). When Mg2+ ions were added, the differences in subpopulations of unfolded nucleosomes in Na+ and K+ environments were 12 ± 5 and 23 ± 7% at the C1 and C2 concentrations of FACT/Nhp6, respectively. Evidently, Na+ ions more efficiently facilitate uncoiling of nucleosomal DNA by FACT/Nhp6 as compared to K+ ions, likely due to the enhanced ability of Na+ to weaken DNA-histone interactions and to increase subpopulation of nucleosomes with DNA unwound near the boundary of a nucleosome (LF-subpopulation in EPR profile). Nhp6 is known to induce considerable bending of DNA (Stillman, 2010). When DNA is tightly wrapped around the histone octamer, Nhp6 accommodates the existing DNA bending, and therefore its binding to a nucleosome does not induce DNA unwrapping (Valieva et al., 2016). Loss or weakening of some DNA-histone interactions facilitates binding of negatively charged regions of FACT to histones, while Nhp6 possibly forms additional interactions with the unwrapped DNA, further increasing (together with FACT) uncoiling of nucleosomal DNA from the octamer.

Fig. 6.

Effect of Na+ and K+ ions on nucleosome interactions with FACT (a,b) and PARP1 (c). (a) Na+ ions support more efficient ATP-independent uncoiling of nucleosomal DNA by FACT/Nhp6 as compared with K+ ions. Nucleosomes N(13,91) were incubated with FACT/Nhp6 at two different concentrations C1 or C2 in Na+ or K+ environment in the presence of 2 mM Mg2+ ions as described in Materials and Methods. (b) Content of uncoiled nucleosomes in Na+ or K+ environment at FACT/Nhp6 concentrations C1 or C2 (mean ± SEM, n = 3) was calculated from the data presented in (a). Statistical significance of differences: *p = 0.01, **p = 0.005. (c) Na+ ions support more efficient reorganization of nucleosome structure by PARP1 as compared with K+ ions. Nucleosomes N(13,91) were incubated with PARP1 as described in Materials and Methods. The EPR profiles (a,c) were averaged over three independent experiments (mean ± SEM) and fitted with two Gaussians. Positions of Gaussian maxima are indicated in (c). (d) A drawing showing reorganization of a nucleosome in the complex with FACT/Nhp6 (Valieva et al., 2016) and in the complex with PARP1 (Sultanov et al., 2017). FACT/Nhp6 induces a large-scale, reversible unwinding of nucleosomal DNA without loss of core histones (Valieva et al., 2016). PARP1 induces reorganization of a nucleosome structure, which is accompanied by an increase in the distance between DNA gyres (Sultanov et al., 2017).

Effect of Cations on PARP1-Nucleosome Interaction

PARP1 is an enzyme and a regulatory protein that facilitates access of repair and transcription regulatory proteins to DNA in chromatin (Caldecott, 2007; Kraus, 2008; De Vos et al., 2012). Our previous in vitro experiments suggest that at least in part this function is mediated by a reversible rearrangement of the nucleosome structure induced by PARP1 binding (Sultanov et al., 2017). Here, we examined whether PARP1-mediated structural changes in nucleosomes depend on the type of monovalent cations present in a solution. Comparative analysis was performed at the PARP1 concentration that induced the formation of ca. 50% PARP1-N(13,91) complexes with rearranged nucleosome structure. In agreement with the previously reported data (Sultanov et al., 2017), PARP1 binding to nucleosome N(13,91) is accompanied by a decrease in a nucleosome subpopulation with EPR ≈ 0.6 and appearance of a nucleosome subpopulation with EPR = 0.4 both in K+ and Na+ environments (Fig. 6c). The observed changes in the EPR profiles reflect a PARP1-induced partial nucleosome unfolding (Sultanov et al., 2017). Equal positions of maxima of the EPR peaks corresponding to the PARP1-nucleosome complexes suggest that the structures of these complexes are similar in K+- and Na+-containing solutions. At the same time, Na+ facilitate the formation of the PARP1-nucleosome complexes more efficiently as compared to K+ (Fig. 6c): at 50 nM PARP1, the contents of the complexes are significantly different ( p = 0.009): 63 ± 2 and 45 ± 4% in Na+- and K+- containing solutions, respectively. Thus, the rearrangement of the nucleosome structure that accompanies PARP1-nucleosome complex formation occurs easier in the presence of Na+ ions and can be explained by the more pronounced weakening of DNA-histone interactions induced by Na+ as compared to K+ ions. It should be noted that the presence of divalent Mg2+ ions (5 mM) does not abolish the differences in Na+ and K+ influence on PARP1-nucleosome complexes.

Our data indicate that K+ and Na+ ions differentially modulate at least two unrelated ATP-independent processes in chromatin: reorganization of nucleosome structure by FACT and PARP1.

Effect of Cations on Transcription of Nucleosomal DNA by Pol II

Next, we questioned whether the efficiency of a process that actively consumes chemical energy is affected by the type of monovalent cations. Transcription through a nucleosome by Pol II is ATP-dependent and accompanied by pausing of the enzyme at several distinct positions within nucleosome (Kireeva et al., 2002). The pattern of pausing reflects changes in the nucleosome structure that occur during transcription (Kulaeva et al., 2009); therefore, the positions and intensities of the pauses can serve as an indicator of the efficiency of formation of the intermediates during transcription (reviewed in Kulaeva et al. (2013)). The pausing pattern can be visualized by detecting the yields of radio-labeled RNA products of different lengths formed during the transcription process (Fig. 7). We have studied whether the pausing pattern (i.e., the efficiency of formation of the intermediates) during transcription of nucleosomal DNA by Pol II is differentially affected by K+ and Na+ ions. In agreement with previously published data (Kireeva et al., 2002; Kulaeva et al., 2009), an increase in ion concentration from 40 to 150 and further to 300 mM progressively facilitates transcription through the nucleosome by Pol II and results in a decrease in the strength of the nucleosomal barrier to Pol II (Fig. 7). However, our experiments did not reveal any considerable differences in the pausing pattern induced by the substitution of K+ by Na+ ions (Fig. 7). Thus, Pol II is an example of the nucleosome processing nuclear protein complex that is functioning nearly independently of the type of monovalent cations present in a solution, but is sensitive to ionic strength.

Fig. 7.

Transcription through a nucleosome by Pol II at different concentrations of KCl and NaCl. (a) The assembled Pol II EC was ligated to the 603 nucleosome. The RNA was pulse labeled in the presence of unlabeled ATP, CTP, and [α−32P]GTP (-UTP mix), and Pol II was stalled at the position of the active center 83 bp upstream of the proximal nucleosome boundary. Then, transcription was resumed by adding all unlabeled NTPs at various concentrations of KCl and NaCl. (b). Analysis of pulse-labeled RNA formed during transcription through a nucleosome by Pol II at different concentrations of KCl and NaCl, by 8% denaturing PAGE. The numbers on the left indicate the length of pulse-labeled RNA (nucleotides), the numbers on the right indicate distances from the promoter-proximal nucleosome boundary (bp).

Conclusions

Our results show that structural features and the stability of nucleosomes as well as the efficiency of protein-induced nucleosome rearrangements strongly depend on ion environment and are controlled not only by the concentration of inorganic ions but also by the type of cations. In particular, Na+ and K+ considerably and differentially affect DNA-histone interactions in nucleosomes and nucleosome transactions at physiological concentrations of the cations.

Our results obtained using mononucleosomes are consistent with the data obtained using polynucleosomal templates (Allahverdi et al., 2015) and suggest that K+ environment is more physiologically relevant for the analysis of interactions between nucleosomes and nuclear proteins in vitro. Accordingly, the results of experiments conducted in Na+ environment in vitro should be extrapolated to in vivo state with some caution.

Sodium ions efficiently stabilize the nucleosome structure at lower concentrations, but the stabilization effect decreases at ion concentrations higher than 40 mM. K+ ions surpass Na+ in the stabilization of a nucleosome structure in the 80–500 mM concentration range. In contrast to Na+, the maximal stabilization of DNA-histone interactions by K+ ions was observed at ca. 80–150 mM (Fig. 4a). Thus, local fluctuations near physiological concentrations of K+ in the nucleus should minimally affect nucleosome stability and transactions. The stabilization effect of K+ ions could contribute to nucleosome positioning on DNA in chromatin.

The regulation of DNA accessibility to various DNA-interacting proteins and protein complexes is an important function of ATP-dependent chromatin remodelers and histone chaperones. Sodium ions likely compete with core histones for the interactions with DNA near the entrance of DNA into nucleosome, enhancing “nucleosome breathing” and thus increasing partial DNA uncoiling from the octamer that, in turn, facilitates the reorganization of the nucleosome structure by histone chaperones like FACT and PARP1. Our data indicate that K+ ions produce a barrier hindering the uncoiling of nucleosomal DNA, and its overcoming is likely an important part of the action of various chromatin-interacting ATP-independent proteins, such as FACT and PARP1. On the contrary, transcript elongation by Pol II depends on chemical energy and appeared to be sensitive to ion strength but not to the cation type. Local intranuclear concentrations of Na+ and K+ ions change during a cell cycle (Strick et al., 2001). We speculate that the action of histone chaperones could be regulated to some extent by local concentrations of specific ions in vivo. Certain ion types could affect the stability of nucleosomes, thus modulating the outcome of chromatin transactions affected by the chaperones.

Supplementary Material

Financial support.

spFRET studies were supported by Russian Science Foundation (grant no. 19–74-30003). PARP1 studies were supported by NIH grant CA220151. Studies of transcription through chromatin were supported by NIH grant RO1GM119398. The research was partially performed using facilities of the Interdisciplinary Scientific and Educational School of Moscow University “Molecular Technologies of the Living Systems and Synthetic Biology.”

Footnotes

Supplementary material. To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1431927621013751.

Conflict of interest. The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Allahverdi A, Chen Q, Korolev N & Nordenskiöld L (2015). Chromatin compaction under mixed salt conditions: Opposite effects of sodium and potassium ions on nucleosome array folding. Sci Rep 5, 8512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biswas D, Yu Y, Prall M, Formosa T & Stillman DJ (2005). The yeast FACT complex has a role in transcriptional initiation. Mol Cell Biol 25, 5812–5822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Böhm V, Hieb AR, Andrews AJ, Gansen A, Rocker A, Tóth K, Luger K & Langowski J (2011). Nucleosome accessibility governed by the dimer/tetramer interface. Nucleic Acids Res 39, 3093–3102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bondarenko VA, Steele LM, Újvári A, Gaykalova DA, Kulaeva OI, Polikanov YS, Luse DS & Studitsky VM (2006). Nucleosomes can form a polar barrier to transcript elongation by RNA polymerase II. Mol Cell 24, 469–479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braunlin WH & Nordenskiöld L (1984). A potassium-39 NMR study of potassium binding to double-helical DNA. Eur J Biochem 142, 133–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buning R & Van Noort J (2010). Single-pair FRET experiments on nucleosome conformational dynamics. Biochimie 92, 1729–1740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldecott KW (2007). Mammalian single-strand break repair: Mechanisms and links with chromatin. DNA Repair 6, 443–453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrivain P, Cournac A, Lavelle C, Lesne A, Mozziconacci J, Paillusson F, Signon L, Victor JM & Barbi M (2012). Electrostatics of DNA compaction in viruses, bacteria and eukaryotes: Functional insights and evolutionary perspective. Soft Matter 8, 9285–9301. [Google Scholar]

- De Vos M, Schreiber V & Dantzer F (2012). The diverse roles and clinical relevance of PARPs in DNA damage repair: Current state of the art. Biochem Pharmacol 84, 137–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feofanov AV, Andreeva TV, Studitsky VM & Kirpichnikov MP (2018). Reversibility of structural rearrangements in mononucleosomes induced by ionic strength. Mosc Univ Biol Sci Bull 73, 157–161. [Google Scholar]

- Gansen A, Hieb AR, Böhm V, Tóth K & Langowski J (2013). Closing the gap between single molecule and bulk FRET analysis of nucleosomes. PLoS One 8, e57018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaykalova DA, Kulaeva OI, Bondarenko VA & Studitsky VM (2009). Preparation and analysis of uniquely positioned mononucleosomes. Methods Mol Biol 523, 109–123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaykalova DA, Kulaeva OI, Pestov NA, Hsieh F-K & Studitsky VM (2012). Experimental analysis of the mechanism of chromatin remodeling by RNA polymerase II. Methods Enzymol 512, 293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hazan NP, Tomov TE, Tsukanov R, Liber M, Berger Y, Masoud R, Toth K, Langowski J & Nir E (2015). Nucleosome core particle disassembly and assembly kinetics studied using single-molecule fluorescence. Biophys J 109, 1676–1685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hibino K, Yoshikawa Y, Murata S, Saito T, Zinchenko AA & Yoshikawa K (2006). Na+ more strongly inhibits DNA compaction by spermidine (3+) than K+. Chem Phys Lett 426, 405–409. [Google Scholar]

- Kireeva ML, Walter W, Tchernajenko V, Bondarenko V, Kashlev M & Studitsky VM (2002). Nucleosome remodeling induced by RNA polymerase II: Loss of the H2A/H2B dimer during transcription. Mol Cell 9, 541–552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klemm SL, Shipony Z & Greenleaf WJ (2019). Chromatin accessibility and the regulatory epigenome. Nat Rev Genet 20, 207–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korolev N, Lyubartsev AP, Rupprecht A & Nordenskiöld L (1999a). Competitive binding of Mg2+, Ca2+, Na+, and K+ ions to DNA in oriented DNA fibers: Experimental and monte carlo simulation results. Biophys J 77, 2736–2749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korolev N, Lyubartsev AP, Rupprecht A & Nordenskiöld L (1999b). Experimental and monte carlo simulation studies on the competitive binding of Li+, Na+, and K+ ions to DNA in oriented DNA fibers. J Phys Chem B 103, 9008–9019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korolev N & Nordenskiöld L (2000). Influence of alkali cation nature on structural transitions and reactions of biopolyelectrolytes. Biomacromolecules 1, 648–655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraus WL (2008). Transcriptional control by PARP-1: Chromatin modulation, enhancer-binding, coregulation, and insulation. Curr Opin Cell Biol 20, 294–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kudryashova KS, Chertkov OV, Nikitin DV, Pestov NA, Kulaeva OI, Efremenko AV, Solonin AS, Kirpichnikov MP, Studitsky VM & Feofanov AV (2015). Preparation of mononucleosomal templates for analysis of transcription with RNA polymerase using spFRET. Methods Mol Biol 1288, 395–412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulaeva OI, Gaykalova DA, Pestov NA, Golovastov VV, Vassylyev DG, Artsimovitch I & Studitsky VM (2009). Mechanism of chromatin remodeling and recovery during passage of RNA polymerase II. Nat Struct Mol Biol 16, 1272–1278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulaeva OI, Hsieh FK, Chang HW, Luse DS & Studitsky VM (2013). Mechanism of transcription through a nucleosome by RNA polymerase II. Biochim Biophys Acta Gene Regul Mech 1829, 76–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langelier MF, Steffen JD, Riccio AA, McCauley M & Pascal JM (2017). Purification of DNA damage-dependent PARPs from E. coli for structural and biochemical analysis. In Methods in Molecular Biology, Tulin A (Ed.), vol. 1608. pp. 431–444. New York, NY: Humana Press Inc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowary PT & Widom J (1998). New DNA sequence rules for high affinity binding to histone octamer and sequence-directed nucleosome positioning. J Mol Biol 276, 19–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyubitelev AV, Studitsky VM, Feofanov AV & Kirpichnikov MP (2017). Effect of sodium and potassium ions on conformation of linker parts of nucleosomes. Mosc Univ Biol Sci Bull 72, 146–150. [Google Scholar]

- Materese CK, Savelyev A & Papoian GA (2009). Counterion atmosphere and hydration patterns near a nucleosome core particle. J Am Chem Soc 131, 15005–15013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onufriev AV & Schiessel H (2019). The nucleosome: From structure to function through physics. Curr Opin Struct Biol 56, 119–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prieto EI & Maeshima K (2019). Dynamic chromatin organization in the cell. Essays Biochem 63, 133–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruone S, Rhoades AR & Formosa T (2003). Multiple Nhp6 molecules are required to recruit Spt16-Pob3 to form yFACT complexes and to reorganize nucleosomes. J Biol Chem 278, 45288–45295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savelyev A & Papoian GA (2006). Electrostatic, steric, and hydration interactions favor Na+ condensation around DNA compared with K+. J Am Chem Soc 128, 14506–14518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stillman DJ (2010). Nhp6: A small but powerful effector of chromatin structure in saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biochim Biophys Acta 1799, 175–180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strick R, Strissel PL, Gavrilov K & Levi-Setti R (2001). Cation-chromatin binding as shown by ion microscopy is essential for the structural integrity of chromosomes. J Cell Biol 155, 899–910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sultanov D, Gerasimova N, Kudryashova K, Maluchenko N, Kotova E, Langelier M-F, Pascal J, Kirpichnikov M, Feofanov A & Studitsky V (2017). Unfolding of core nucleosomes by PARP-1 revealed by spFRET microscopy. AIMS Genet 4, 21–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valieva ME, Armeev GA, Kudryashova KS, Gerasimova NS, Shaytan AK, Kulaeva OI, McCullough LL, Formosa T, Georgiev PG, Kirpichnikov MP, Studitsky VM & Feofanov AV (2016). Large-scale ATP-independent nucleosome unfolding by a histone chaperone. Nat Struct Mol Biol 23, 1111–1116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vieregg J, Cheng W, Bustamante C & Tinoco I (2007). Measurement of the effect of monovalent cations on RNA hairpin stability. J Am Chem Soc 129, 14966–14973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zinchenko AA & Yoshikawa K (2005). Na+ shows a markedly higher potential than K+ in DNA compaction in a crowded environment. Biophys J 88, 4118–4123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.