Abstract

Objective:

To perform a blind comparative evaluation of the quality of orthodontic treatment provided by orthodontists and general dentists.

Materials and Methods:

Sixty cases of orthodontic treatment were evaluated—30 treated by specialists in orthodontics and 30 treated by general dentists with no specialization course. Orthodontists were selected randomly by lots, in a population of 1596 professionals, and recordings were performed based on the guideline established by the Objective Grading System proposed by the American Board of Orthodontics. Each participant was asked to present a case considered representative of the best outcome among the cases treated, regardless of the type or initial severity of the malocclusion. Statistical analysis involved the chi-square, Wilcoxon, and Mann-Whitney tests. The level of significance was set at P = .05 for the statistical tests.

Results:

The results showed that 29 orthodontists (96.7%) presented cases considered satisfactory and would be approved on the qualification exam, whereas only 15 dentists (50%) had cases considered satisfactory. Moreover, treatment time was significantly shorter among the orthodontists (P = .022), and the posttreatment comparison revealed that orthodontists achieved better outcomes considering all the variables studied.

Conclusions:

Orthodontists spend less time on treatment and achieve better quality outcomes than cases treated by general dentists who have not undergone a specialization course in orthodontics.

Keywords: Orthodontics, Dentist's practice patterns, Single-blind method

INTRODUCTION

The assessment of the results of orthodontic treatment involves the determination of functional, morphologic, and esthetic aspects as well as stability over the years.1 Such assessments assist in establishing goals, setting standards, and determining methods for measuring the quality of orthodontic outcomes. Moreover, assessments are useful for educational purposes in postgraduate programs in orthodontics, contributing to the technical and scientific improvement of oral healthcare professionals.2

The literature reports that 20% to 50% of all orthodontic treatment is performed by general dentists with no certificate of specialization in orthodontics.3–5 While there is no legal basis for impeding general dentists from providing orthodontic treatment, society needs scientific parameters that allow the choice of oral healthcare professionals who are capable of providing the best care in terms of quality orthodontic treatment. Thus, knowledge of the experience of orthodontic communities in different countries can favor the proper political and administrative conduct of institutions involved in orthodontics as a science.

A critical evaluation of the literature reveals that most studies on the assessment of the results of orthodontic treatment address aspects related to treatment performed by specialists and postgraduate students. Such studies focus specifically on variables that contribute toward the success or failure of treatment.6–15 On the other hand, there are few studies on the quality of orthodontic treatment offered by general dentists.16 Thus, a number of issues have frequently arisen in the orthodontic scientific community, such as whether the results of orthodontic treatment provided by general dentists meet the criteria of quality considered satisfactory and whether clinical excellence is indeed needed in the outcome of treatment. Furthermore, some dental programs do not offer a comprehensive course in orthodontics. So how do the general dentists acquire adequate information as to how to treat a case?

The aim of the present study was to perform a blind comparative evaluation of the quality of orthodontic treatment provided by orthodontists and general dentists based on the guideline established by the Cast/Radiograph Evaluation (C-R Eval)13 proposed by the American Board of Orthodontics (ABO).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This study received approval from the Human Research Ethics Committee of Vale do Rio Verde University – UNINCOR. The sample size was based on data on the mean and standard deviation (SD) scores of a previous study.16 Estimating that a clinically significant difference between two groups would be 1 SD and adopting an effect size of 0.5, a sample size of 27 in each group would give a 95% power to detect this as difference at a significance level of .05. In order to compensate for possible losses, 30 models were actually recruited. Thus, the quality of the outcome of 60 cases of orthodontic treatment was evaluated—30 treated by specialists in orthodontics and 30 treated by general dentists with no specialization course.

All participants were residents of the state of Minas Gerais, which is the second most populous state in Brazil, with approximately 20 million inhabitants. Documentation consisted of initial and final study models as well as initial and final panoramic radiographs. Orthodontists and dentists were selected randomly by lots using the list provided by the Regional Dentistry Board as reference, which contained all duly registered specialists in orthodontics (n = 1596). Once an orthodontist had been selected, the researcher contacted him/her, explained the study objectives and solicited documentation for analysis. In cases of refusal, an additional lot was drawn. For each orthodontist selected, the researcher contacted a general dentist in the same city by telephone who agreed to participate in the study. Each participant was asked to present a case considered representative of the best outcome among the cases treated, regardless of the type or initial severity of the malocclusion.

The C-R Eval analyzes seven criteria on plaster models: alignment, marginal ridges, buccolingual inclination, occlusal contacts, occlusal relationships, overjet, and interproximal contacts. The eighth criterion uses panoramic radiographs for the determination of root angulation. For measurements and calibration, the researcher used the calibration kit adopted by the ABO, which contains three pairs of models with their respective scores (made by an examiner of the ABO), the classification system manual, a ruler for measuring irregularities and a CD-ROM with instructions.13

Based on the C-R Eval, possible subtracted points total 380. A case that loses less than 20 points (5.3%) is approved, and a case that loses more than 30 points (7.9%) fails. Cases losing between 20 and 30 points may be approved provided there is quality in the documentation, a treatment plan with appropriate objectives, satisfactory positioning of the maxilla, mandible, upper and lower teeth, and adequate facial profile.13 However, the present study only considered cases to be satisfactory when losing fewer than 20 points due to the fact that the orthodontists and dentists had chosen cases with their best results, thereby presupposing greater rigor in the evaluation.

All pairs of models were numbered and coded by a research assistant such that the researcher had no knowledge regarding the type of oral healthcare professional who had performed the treatment. The researcher then underwent a training exercise using the ABO kit and instructions. Intraexaminer agreement was determined using new measurements of the initial and final models of five randomly selected patients, with a 15-day interval between the first and second measurements. For the assessment of causal error, the standard deviation of the error was calculated using the Dahlberg formula: SDe = √(ΣD2 / 2N).17 Concordance was assessed using the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC). The causal errors were small and acceptable. The largest causal error occurred for the alignment measurement, achieving a value of 1.095. ICC values ranged from 0.80 to 0.91, demonstrating good intraexaminer agreement.

The statistical analysis was performed using SPSS for Windows 17 (SPSS, Chicago, Ill). The data were submitted to a variance homogeneity test (Levene test) and normality test (Shapiro-Wilk). These tests revealed that nonparametric tests should be employed in the data analysis. The Wilcoxon test was used to determine associations between variables within the same group before and after treatment (P ≤ .05). The Mann-Whitney U-test was used for comparisons of variables before and after treatment performed by orthodontists and general practitioners (P ≤ .05). The Mann-Whitney U-test was also used for comparisons of treatment time and patient age between groups (P ≤ .05). The chi-square test was used for the assessment of patient gender in both groups (P ≤ .05).

RESULTS

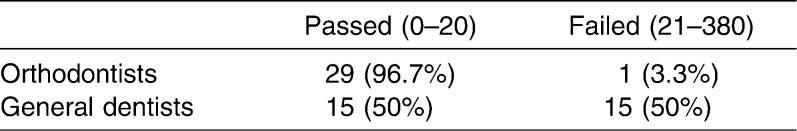

Thirty-six orthodontists were selected from different cities in the state of Minas Gerais, six of whom did not agree to participate in the study. For the selection of the general dentists, 328 telephone contacts were made until reaching the sample of 30 dentists. Based on ABO criteria, 29 orthodontists (96.7%) presented cases considered satisfactory and would be approved on the qualification exam, whereas only 15 dentists (50%) had cases considered satisfactory (Table 1).

Table 1.

Number and Percentage of Cases Treated by Orthodontists and General Dentists Considered Passed or Failed Based on ABO Criteria

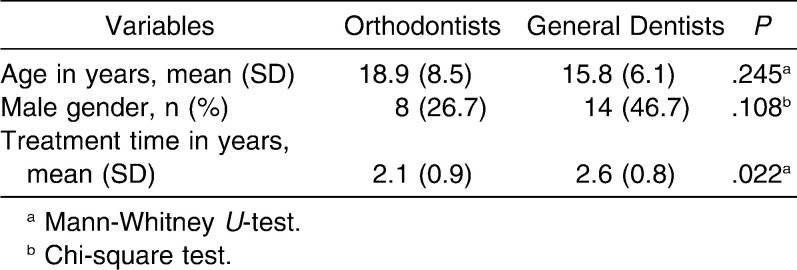

No significant differences were found with regard to gender or age of the patients treated by the orthodontists and dentists. However, treatment time was significantly shorter among the orthodontists (P = .022) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Comparison of Variables Related to Patients (Age and Gender) and Treatment Time Between Cases Treated by Orthodontists and General Dentists

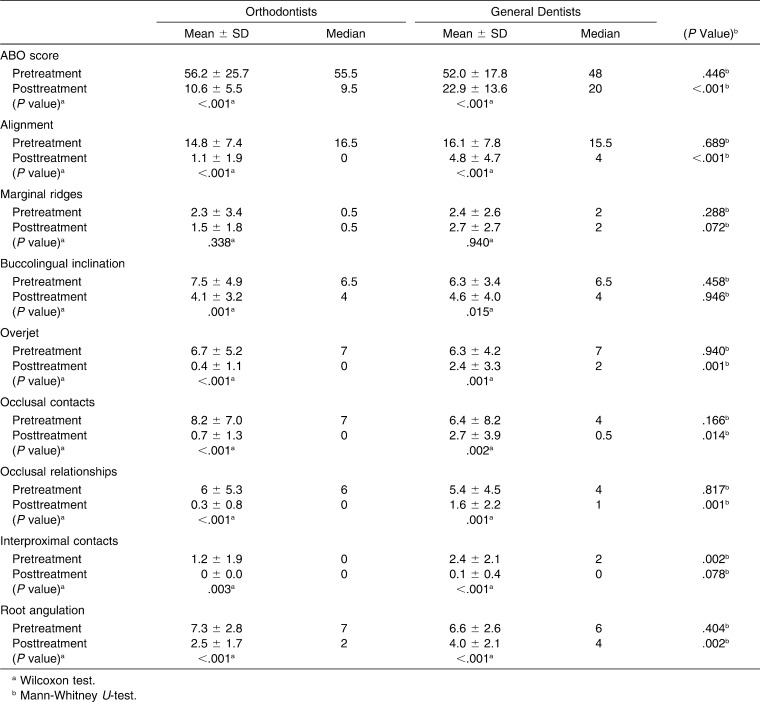

Significant reductions in the number of negative points occurred for all variables between the pretreatment and posttreatment evaluations for both groups of orthodontists and dentists. However, greater statistical significance in these changes was detected in the cases treated by orthodontists (Table 3).

Table 3.

Results of American Board of Orthodontics (ABO) Criteria Before and After Treatment Performed by Orthodontists and General Dentists

The pretreatment comparison revealed that the orthodontists and dentists selected cases with similar degrees of severity, except with regard to “interproximal contact” (P = .002). The posttreatment comparison revealed that orthodontists achieved better outcomes considering all the variables studied, except “buccolingual inclination,” for which no statistically significant difference was detected (Table 3).

DISCUSSION

Decisions based on evidence regarding treatment need and efficacy are the mark of excellence in healthcare in the 21st century.18 The findings of the present study indicate that the quality of orthodontic treatment offered by general dentists who had not undergone a specialization course in orthodontics was unsatisfactory in most cases. Moreover, the general practitioners spent approximately 5 months longer to complete treatment in comparison to the orthodontists. Mascarenhas and Vig19 found that orthodontists spent longer than postgraduate students on treatment, but also achieved better outcomes. The implications of the results of the present study encompass aspects of a financial nature as well as those related to oral health. Thus, these findings offer evidence that underscores the importance of a specialization course as a prerequisite for the practice of orthodontics.

The primary considerations of parents when seeking orthodontic treatment for their children are cost and the perception of the effectiveness of treatment.20 Moreover, parents are more concerned with esthetics than functional alterations stemming from malocclusion.20 However, patients are unable to determine differences in the results of treatment provided by specialists and general practitioners.16 These factors certainly explain the reasons for the considerable offer of orthodontic treatment on the part of general dentists. Moreover, specialization courses are relatively expensive, especially for recent graduates of dentistry, which may be one of the reasons why a large number of dentists do not seek to expand their professional knowledge.

The results of the present study are in agreement with those reported by Abei et al.16 who evaluated 196 cases and found that the mean overall score of patients treated by 70 specialists was significantly lower than that of patients treated by general practitioners. Alignment was the criterion that most contributed to this difference in both studies, indicating that this variable is a critical factor regarding the quality of treatment offered by general dentists who have not undergone a specialization course.

It should be stressed that the C-R Eval as applied in this study was not designed to measure pretreatment case complexity, unfavorable craniofacial growth pattern, or patient cooperation, which are important factors with regard to treatment success. However, the initial models of each case were measured in the present study only as comparative features. The authors were not interested in comparing the initial severity of the cases, since each professional was free to choose his/her own best patient. The absence of significant systematic errors and the low number of causal errors observed in the present study demonstrate the precision of the measurements, thereby characterizing the ABO evaluation system as reliable and reproducible, which adds credibility to the results. Moreover, the fact that both the orthodontists and dentists who participated in the study were from different schools reduces the chances of bias.

Another important aspect is that we do not know anything on the quality of orthodontic training of those general dentists who passed based on the ABO criteria. The results should not mislead the reader that 50% of the general dentists can provide adequate orthodontic treatment. In other words, all in all the ABO system gives an indication how precise the clinician is by looking at their treatment results to evaluate their clinical competencies. That does not give any indication of their knowledge of diagnosis and treatment planning.

Through a demonstration of the quality of service, healthcare professionals enhance their reputation and job satisfaction.21 It is therefore important to point out that all participants in the present study were volunteers and believed they were providing the best possible care for their patients. Thus, the results of the present study may favor clinical conduct among both orthodontists and dentists alike by identifying their errors and contributing toward further improvement with regard to the results of future treatment.

CONCLUSION

For the current sample of cases that was submitted for evaluation, orthodontists spend less time (21.±0.9 versus 2.6±0.8 years) on treatment and achieve better quality outcomes (96.7% versus 50% passed ABO criteria) than cases treated by general dentists who have not undergone a specialization course in orthodontics.

REFERENCES

- 1.Freitas K. M. S, Freitas M. R, Janson G, Henriques J. F. C, Pinzan A. Avaliação pelo índice PAR dos resultados do tratamento ortodôntico da má oclusão de Classe I tratada com extrações. R Dental Press Ortodon Ortop Facial. 2009;2:94–104. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Faber J. O board Brasileiro de Ortodontia. R Dental Press Ortodon Ortop Facial. 2009;14:5. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jacobs R. M, Bishara S. E, Jakobsen J. R. Profiling providers of orthodontic services in general dental practice. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1991;99:269–275. doi: 10.1016/0889-5406(91)70008-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wolsky S. L, McNamara J. A. Orthodontic services provided by general dentists. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1996;110:211–217. doi: 10.1016/s0889-5406(96)70111-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vicéns J, Russo A. Comparative use of Invisalign by orthodontists and general practitioners. Angle Orthod. 2010;3:425–434. doi: 10.2319/052309-292.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gotlieb E. L. Grading your orthodontic treatment results. J Clin Orthod. 1975;3:155–161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pickering E. A, Vig P. The occlusal index used to assess orthodontic treatment. Br J Orthod. 1975;1:47–51. doi: 10.1179/bjo.2.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berg R. Postretention analysis of treatment problems and failures in 264 consecutively treated cases. Eur J Orthod. 1979;1:55–68. doi: 10.1093/ejo/1.1.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eismann D. Reliable assessment of morphological changes resulting from orthodontic treatment. Eur J Orthod. 1980;1:19–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Elderton R. J, Clark J. D. Orthodontic treatment in the general dental service assessed by the Occlusal Index. Br J Orthod. 1983;4:178–186. doi: 10.1179/bjo.10.4.178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Richmond S, Shaw W. C, O'Brien K. D, Buchanan I. B, Jones R, Stephens C. D, Roberts C. T, Andrews M. The development of the PAR Index (Peer Assessment Rating): reliability and validity. Eur J Orthod. 1992;2:125–139. doi: 10.1093/ejo/14.2.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Buchanan I. B, Shaw W. C, Richmond S, O'Brien K. D, Andrews M. A comparison of the reliability and validity of the PAR Index and Summers Occlusal Index. Eur J Orthod. 1993;1:27–31. doi: 10.1093/ejo/15.1.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Casko J. S, Vaden J. L, Kokich V. G, et al. Objective grading system for dental casts and panoramic radiographs. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1998;114:589–599. doi: 10.1016/s0889-5406(98)70179-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pangrazio-Kulbersh V, Kaczynski R, Shunock M. Early outcome assessed by the Peer Assessment Rating index. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1999;115:554–560. doi: 10.1016/s0889-5406(99)70277-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.King G. J, McGorray S. P, Wheeler T. T, Dolce C, Taylor M. Comparison of Peer Assessment Ratings (PAR) from 1-phase and 2-phase treatment protocols for Class II malocclusions. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2003;123:489–496. doi: 10.1067/mod.2003.S0889540603000453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abei Y, Nelson S, Amberman B. D, Hans M. G. Comparing orthodontic treatment outcome between orthodontists and general dentists with the ABO index. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2004;126:544–548. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2003.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Houston W. J. B. The analysis of errors in orthodontic measurements. Am J Orthod. 1983;83:382–390. doi: 10.1016/0002-9416(83)90322-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ackerman M. B, Rinchuse D. J, Rinchuse D. J. ABO certification in the age of evidence and enhancement. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2006;130:133–140. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2005.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mascarenhas A. K, Vig K. Comparison of orthodontic treatment outcomes in educational and private practice settings. J Dent Educ. 2002;66:94–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marques L. S, Pordeus I. A, Ramos-Jorge M. L, Filogônio C. A, Filogônio C. B, Pereira L. J, Paiva S. M. Factors associated with the desire for orthodontic treatment among Brazilian adolescents and their parents. BMC Oral Health. 2009;18:29–34. doi: 10.1186/1472-6831-9-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Richmond S, Daniels C. P. International comparisons of professional assessment in orthodontics: Part 1—treatment need. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1998;113:180–185. doi: 10.1016/s0889-5406(98)70290-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]