Abstract

BK polyomavirus (BKPyV) is a ubiquitous pathogen that typically results in asymptomatic infection. However, in immunocompromised individuals, BKPyV viral shedding in the urine can reach 109 copies per mL. These high viral levels within urine provide ideal samples for next-generation sequencing to accurately determine BKPyV genotype and identify mutations associated with pathogenesis. Sequencing data obtained can be further analyzed to better understand and characterize the genetic diversity present in BKPyV. Here, methods are described for the successful extraction of viral DNA from urine and the subsequent amplification methods to prepare a sample for next-generation sequencing.

Keywords: BK polyomavirus (BKPyV), Diversity, Variation, Genotype, Rolling circle amplification

1. Introduction

BK polyomavirus (BKPyV, Family Polyomaviridae, Genus Betapolyomavirus) – also known as human polyomavirus 1 – is a double-stranded DNA virus with a circular genome. The genome is approximately 5 kilobase pairs (kbp). Worldwide seroprevalence rates approach 90 % by age 10 years (Knowles, 2006). Initial infection is asymptomatic followed by a life-long persistent infection within the urogenital tract and typically remains asymptomatic in immunocompetent individuals.

In healthy individuals, BKPyV shedding occurs in approximately 10 % of urine samples with the absence of symptoms (Kling et al., 2012). Viral shedding in the urine (viruria) in immunocompromised individuals is more frequent and occurs in over 70 % of patients with a CD4 count <200 cells/mm3 (Hu et al., 2018). Viruria is also detected in individuals after kidney or hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT); however, unlike other immunocompromised populations, this can result in a symptomatic infection. Viruria is more common than detection of BKPyV in the blood (viremia) and is typically associated with high viral loads that may exceed 109 copies/mL.

BKPyV exists as four genotypes and multiple sub-genotypes (reviewed in Blackard et al., 2020). Genotype I is the most prevalent worldwide. Genotype IV is commonly reported in East Asia, while genotypes II and III are rarely reported (Yogo et al., 2009). The classification of BKPyV genotypes was first established using a variable region – amino acids 61–83 – within the VP1 structural gene (Li et al., 1993). Nonetheless, the presence of viral polymorphisms, as well as recombination outside of this region have been identified, and full genome analysis should be considered for rigorous and accurate determination of genotypes. To fully understand the consequences of mutations, viral diversity of BKPyV must be investigated by increasing the available sequencing data.

There are no published methods for the effective extraction of BKPyV from urine, subsequent amplification, and sequencing. The ability to obtain viral genomic data from non-invasive sources, such as urine, can provide important insights into BKPyV variability and evolution on a scale not previously possible.

2. Methods

2.1. Human samples

Urine samples from a previously established cohort were evaluated (Laskin et al., 2019). Briefly, subjects were enrolled from the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP) and Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center (CCHMC) who were older than 2 years of age and undergoing their first allogeneic HSCT. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards at the CHOP, CCHMC, and the University of Cincinnati. Stored urine samples were confirmed for BKPyV infection by quantitative real-time PCR using an assay with a dynamic range of 500 to 1 × 1010 copies/mL (Laskin et al., 2019). The BKPyV quantified in patient urine samples spanned this wide dynamic range. Although the procedure was followed regardless of viral load, samples included those with high (>108 copies/mL), medium (105 to 108 copies/mL), and low (<105 copies/mL) viral loads for later analysis.

2.2. Viral DNA extraction

For the current study, viral DNA was extracted from 1 mL of urine using the QIAamp UltraSens Virus Kit (Qiagen). Manufacturer’s instructions were followed with minor modifications to accommodate urine as the biological sample. Briefly, a room temperature sample was lysed, and precipitated with Buffer AC and carrier RNA, mixed and incubated as directed. The sample was then centrifuged at 4000 g for 4 min, instead of the recommended 1200 g for 3 min. The supernatant was then removed, resuspended in Buffer AR and proteinase K, and incubated as directed. Buffer AB was added, and the mixture was added to the QIAamp spin column and centrifuged at 3000 g. The two wash steps were performed as specified as well as an additional full speed, 1 min centrifugation of the column with no buffer. Two elution steps were performed, each with 30 μL of water. The concentration of the eluted DNA was quantified on a NanoPhotometer (Implen), and aliquots were stored at −20 °C for future use.

2.3. Rolling circle amplification

For rolling circle amplification (RCA) of circular DNAs, EquiPhi29 polymerase (Thermo Fisher) was used with the denatured mix consisting of 4 μL of EquiPhi29 reaction buffer, 1 μL of extracted viral DNA, and 1 μL of each RCA primer listed in Table 1. The mixture was heated to 95 °C for 3 min and placed on ice for 5 min. A reaction mix was made consisting of 0.4 μL of 100 mM DTT (included in EquiPhi kit), 4 μL of 10 mM dNTPs (Thermo Fisher), 2 μL of EquiPhi29 polymerase, and 19.6 of μL water. The mix was vortexed, combined with the denatured mix, incubated at 45 °C for 3 h, and at 65 °C for 10 min to terminate the reaction.

Table 1.

Primer sequences used in this study.

| Primer | Use | Primer sequence (5′-> 3′) | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| BK1731F | Full-length | GGG GGA TCC AGA TGA AAA | (Chen et al., 2004) |

| PCR | CCT TAG GGG CTT TAG | ||

| BK1739R | Full-length | GGA TCC CCC ATT TCT GGG | (Chen et al., 2004) |

| PCR | TTT AGG AAG CAT TCT AC | ||

| VP1-F | Nested VP1 | TGG ACT TAA GAA ATC AAC | (Sahoo et al., 2015) |

| PCR | AAA GTG TAC ATT CAG GA | ||

| VP1-R | Nested VP1 | CTG CTG AAG ATT CCC AAA | (Sahoo et al., 2015) |

| PCR | GGT CAG AC | ||

| PBK761For | EquiPhi | AGC ACT KTT GGG GGA CCT | (Peretti et al., 2018) |

| RCA | AGT TGC | ||

| PBK785For | EquiPhi | TGT DTC TGA GGC TGC TGC | (Peretti et al., 2018) |

| RCA | TGC | ||

| PBK740Rev | EquiPhi | TGG CAA CTA GGT CCC CCA | (Peretti et al., 2018) |

| RCA | AMA GTG | ||

| BKJC-VP1A | EquiPhi | AAG CAT ATG AAG ATG GCC | (Peretti et al., 2018) |

| RCA | CCA | ||

| PBK4934Rev | EquiPhi | TGG ATA GAT TGC TAC TGC | (Peretti et al., 2018) |

| RCA | WTT GAY TGC T | ||

| BKJC-VP1B | EquiPhi | CTG CTC CTC AAT GGA TGT | (Peretti et al., 2018) |

| RCA | TGC C | ||

| BKJC-VP1Drev | EquiPhi | CTC TGG ACA TGG ATC AAG | (Peretti et al., 2018) |

| RCA | CAC | ||

| BKJC-VP1Frev | EquiPhi | GGA ARG AAA GGC TGG ATT | (Peretti et al., 2018) |

| RCA | YWG | ||

| BKJC-VP1Grev | EquiPhi | TYA GGC CWG TWG CTG AYT | (Peretti et al., 2018) |

| RCA | TTG C |

For the TempliPhi procedure, the TempliPhi amplification kit (Cytiva) was used according to the manufacturer’s instructions. In short, 1 μL of extracted DNA and 5 μL of sample buffer were combined, denatured at 95 °C for 3 min, and placed on ice. A premix of 5 μL of reaction buffer and 0.2 μL of enzyme mix was combined. 5 μL of the premix was added to the sample mix and incubated at 30 °C for 18 h, followed by an inactivation step at 65 °C for 10 min.

Both reactions were performed in a thermocycler with a heated lid. Products of both reactions were stored at −20 °C for future use.

2.4. BamHI digest

To linearize the RCA product for PCR amplification, 1 μL of the RCA reaction was mixed with 1 μL of BamHI (New England Biolabs), 2.5 μL of NEBuffer 3.1, and 20.5 μL of water. The mix was incubated at 37 °C for 1 h.

2.5. PCR

LongRange PCR Kit (Qiagen, discontinued) was performed to amplify the full-length BKPyV genome, as well as the VP1 region, using primers listed in Table 1. Each full-length reaction consisted of 1 μL of RCA product post-BamHI digestion, 5 μL of buffer, 2.5 μL of dNTP mix, 2 μL of forward and reverse primers (0.4 μmol), 37.1 μL of water, and 0.4 μL of enzyme mix. Cycling conditions were 93 °C for 2 min, 10 cycles of 93 °C for 30 s, 55 °C for 60 s, 68 °C for 5.5 min, followed by 30 cycles of 93 °C for 30 s, 65 °C for 60 s, 68 °C for 10 min, and 68 °C for 30 min, and a 4 °C hold. For the nested PCR to amplify the viral VP1 region, the reaction mix was prepared in the same manner, with the input DNA being the full-length BKPyV PCR product instead of the RCA product. The cycling conditions were 93 °C for 3 min, 35 cycles of 93 °C for 15 s, 55 °C for 1.5 min, 68 °C for 1.5 min, and a 4 °C hold.

Similar success was obtained with the successor kit – UltraRun LongRange PCR Kit (Qiagen) – with updated cycling conditions. The reaction set up is the same for both PCR reactions and includes 5 μL of UltraRun LongRange PCR Master Mix, 1 μL each of the forward and reverse primers, 1 μL of input DNA – either RCA product or the full-length BKPyV PCR product – and 12 μL of water. The cycling conditions for the full-length reaction is 93 °C for 3 min, 25 cycles of 93 °C for 30 s, 59 °C for 15 s, 68 °C for 3 min, followed by 72 °C for 10 min and a 4 °C hold. The cycling conditions for the nested VP1 PCR is 93 °C for 3 min, 25 cycles of 93 °C for 30 s, 55 °C for 15 s, 68 °C for 1.5 min, followed by 72 °C for 10 min and a 4 °C hold.

2.6. Agarose gel

All RCA, after BamHI digestion, and PCR products were run on a 1% agarose gel. DNA was extracted using the QIAEX II gel extraction kit (Qiagen).

2.7. Sequencing

BKPyV samples were sent to the University of Cincinnati College of Medicine Genomics, Epigenomics and Sequencing Core. Library preparation was completed with the NEB NEBNext Ultra II FS DNA library prep kit, followed by sequencing on an Illumina HiSeq 1000 sequencer with SR 1 × 51 bp. Resulting reads were run through FastQC, aligned to the Dunlop BKPyV reference, and a consensus sequence was generated in UGENE version 37.0 as described previously (Odegard et al., 2021).

2.8. Phylogenetic analysis

Phylogenetic analysis utilized the Bayesian Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) approach implemented in the Bayesian Evolutionary Analysis by Sampling Trees (BEAST) program version 1.10.4 (Suchard et al., 2018). Settings included an uncorrelated relaxed clock, the HKY substitution model, and a nucleotide site heterogeneity with a gamma distribution. A MCMC chain length of 1,000,000,000 was used and visualized in Tracer version 1.7.1 to confirm chain convergence. The effective sampling size values were >1,000, indicating adequate sampling. In Tree Annotator version 1.10.4, a maximum clade credibility tree was selected after a 10 % burn-in and was visualized in FigTree version 1.4.4. Genetic distances between BKPyV sequences were calculated in MEGA X version 10.2.4.

3. Results

Our modifications of the QIAamp UltraSens Virus Kit optimized the use of urine as a biological sample. The kit is intended for use of serum or plasma; however, the adjustments of centrifugation speed and time enabled reliable BKPyV DNA isolation from urine as seen by the quantifiable viral DNA detected post-extraction, as well as the downstream amplification in the samples tested.

RCA utilizes the phi29 polymerase to non-specifically amplify any circular DNA present within a sample. Two commercially available phi29 polymerases – EquiPhi and TempliPhi – were compared to determine which was best suited for amplifying BKPyV in patient urine samples. EquiPhi utilizes Thermo Scientific’s proprietary phi29 DNA polymerase and allows for more protocol customization, while TempliPhi is Cytiva’s proprietary amplification kit. The EquiPhi polymerase includes a buffer and DTT, while the user adds dNTPs and selects either virus-specific or random primers; we utilized BKPyV-specific primers. TempliPhi does not disclose the exact contents, but includes a sample buffer, reaction buffer, and enzyme mix. The sample buffer utilizes random hexamers as primers. RCA requires digestion with BamHI to linearize the product for visualization on an agarose gel and for future PCR amplifications.

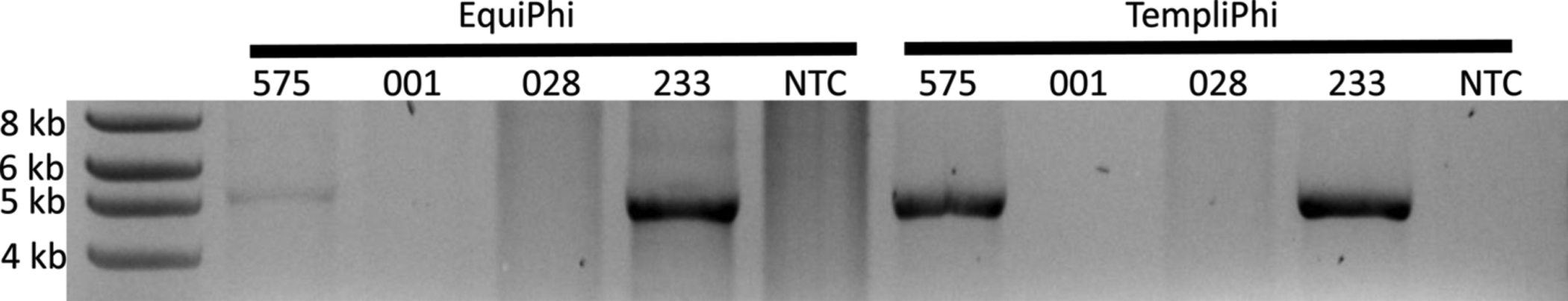

Both TempliPhi and EquiPhi were utilized according to the manufacturers’ instructions and evaluated using both high and low viral load samples from four subjects. Each used 1 μL of extracted DNA, a 1 h BamHI digestion, and visualization of reaction products on a 1% agarose gel (Fig. 1). Both methods yielded visible 5 kb bands representing the full-length BKPyV genome. However, EquiPhi had more background, as well as faint non-specific bands. Thus, the TempliPhi was selected for additional use.

Fig. 1.

Comparison of RCA methods followed by a 2 h BamHI digestion, visualized on 1% agarose gel. Input DNA was 1 μL in all cases. Subjects 575 and 233 had high viral load samples, while subjects 001 and 028 had low viral loads. Both methods yielded 5 kb bands, although the EquiPhi method had more background. NTC = no template control.

Following extraction. RCA and BamHI digest, a full-length PCR was performed on the two low viral load samples – 1 and 28 – although neither yielded visible 5 kb bands (results not shown). Another RCA reaction was performed in which the amount of input DNA was increased from 1 to 3 μL. This RCA, after BamHI digestion, also yielded no positive 5 kb bands. The product was then used as input DNA in a full-length PCR and run on a 1% agarose gel (Fig. 2). Subject 028 had a positive 5 kb band when using 2 μL or 3 μL of extracted DNA.

Fig. 2.

Amplification of low viral load patient samples using TempliPhi RCA protocol with varying volumes of input DNA (1, 2, 3 μL). Following BamHI restriction enzyme digest and full-length PCR imaged on a 1% agarose gel. In low viral load subjects, increasing the input DNA to RCA resulted in a visible downstream product in some cases. NTC = no template control.

Following RCA reactions, digestion times with BamHI enzyme were evaluated to ensure full digestion of the product using a single subject sample (Fig. 3). The contents of each reaction were identical but with the digestion time set at 1, 2, 4, or 24 h. Digestions took place in a thermocycler at 37 °C with a heated lid. BamHI does not require heat inactivation, and at the end of digestion time, the reaction tubes were placed at −20 °C. No change in product visualized on an agarose gel was observed across all times tested. Thus, a 1 h digestion was selected for subsequent experiments.

Fig. 3.

BamHI restriction enzyme digest after TempliPhi RCA. Each digestion contained 1 μL of BamHI, 2.5 μL of buffer, 1 μL of RCA product, and 20.5 μL of water. Reaction conditions were 37 °C for 1, 2, 4, or 24 h, and results were visualized on a 1% agarose gel.

Using a patient sample with a high viral load (Odegard et al., 2021), serial dilutions of the extracted DNA were performed up to 1:1,000,000, 000, and 1 μL of each dilution was used in the following TempliPhi RCA reaction. BamHI digestion was performed for 1 h, and the products were run on a 1% agarose gel (Fig. 4). Positive 5 kb bands were observed for the 1:1, 1:10, and 1:100 dilutions. The RCA products were then used as input DNA in a full-length PCR. All dilutions between 1:1 and 1:1,000, 000 had visible 5 kb products.

Fig. 4.

Serial dilutions of DNA extracted from a high viral load patient was performed to 1:1b. A) RCA of diluted samples was performed with TempliPhi, followed by a 1 h BamHI digestion. Visible 5 kb products were observed for the first 3 dilutions (1:100). B) The products of A were used as input for full-length PCR, and visible 5 kb products were observed up to the 1:1 m dilution. C) The products of B were used as input for a nested VP1 PCR. Visible 1.6 kb products were observed up to the 1:1 m dilution. NTC = no template control.

In order to determine if any of these amplification steps dramatically altered the resulting sequencing data, a single patient sample was analyzed. Both urine and plasma samples were collected, and 1 mL aliquots were processed on two separate occasions. Samples were submitted for next generation sequencing at various steps of this process, including after BamHI digestion, both before and after gel purification, and after full-length PCR and gel purification. For each NGS sample, a consensus sequence was generated and aligned to representative BKPyV references. As shown in Fig. 5, all sequences from this patient cluster together with minimal genetic differences between sequences (average: 0.17 %; range: 0.00 % to 0.40 %). A consensus sequence for was generated from all sequences and is available in GenBank, MZ189087 (accession number assigned but not yet published).

Fig. 5.

Subject 717 urine (U) and plasma (P) samples were processed on two separate occasions (labeled 1 or 2). Samples were submitted for next-generation sequencing after RCA and BamHI digest (A), that product run on a 1% agarose gel, the 5 kb band was cut out and DNA extracted (B) or following full-length PCR, 1% agarose separation and extraction (C). Sequences were compared to representative BKPyV sequences (labeled by GenBank accession number and country of origin). All 717 sequences branch from the node circled. Evolutionary distance between these sequences is 0.17 %.

4. Discussion

Urine from immunocompromised hosts represents an abundant source of BKPyV DNA. Several studies have analyzed urine samples to identify and quantify the presence of the polyomaviruses (Kluba et al., 2015; Pang et al., 2008). However, the study of BKPyV diversity is severely limited compared to other viruses and can help identify the impact on pathogenesis, replication, cell tropism at both the individual and population level (Blackard et al., 2020). An initial study utilized urine from subjects to evaluate quasispecies within the VP1 region of BKPyV (Luo et al., 2012). Since then, few studies have investigated quasispecies diversity further, and urine remains an underutilized biological sample to study BKPyV diversity. In the current study, an optimized methodology to extract, amplify, and sequence BKPyV from urine is provided. This methodology generates abundant viral genomic data from samples with positive BKPyV regardless of viral load and can then be used to study BKPyV variability at the individual and population levels.

Viral DNA extraction from urine can be accomplished with 1 mL of urine and the use of a commercially available kit. Step 5, when samples are centrifuged at 4000 g for 4 min, of the QIAamp UltraSens Virus Kit is a vital step in this process. In some samples, debris remains in the supernatant after centrifugation. In this case, a short 5 s centrifugation is necessary to fully form a pellet. While some samples will have no visible pellet and no debris in the supernatant, it is important to continue with the procedure and remove the supernatant, avoiding touching the sides of the microcentrifuge tube with the pipette tip. Following DNA extraction, quantification of DNA present in samples is suggested, as some samples may not have detectable DNA due to low viral copy number or low-quality sample collection/processing.

Comparing commercially available RCA kits illustrated the benefit of using random hexamers over specific primers, as previous studies have used (Rockett et al., 2015). Although specific primers have been seen to be effective, the use of non-specific primers reduces background and results in a cleaner product for future use. Optimization of the restriction enzyme digest demonstrated an effective digest within 1 h to minimize reaction time. The PCR reaction conditions for both the discontinued LongRange PCR kit and the successor UltraRun LongRange PCR kit effectively amplify with the given primers. Performing RCA prior to PCR increases the number of positive samples, thus increasing the sequencing data obtained. Further, the consensus sequences from NGS-derived PCR products are nearly identical for all preparations and manipulations of the input DNA.

In summary, this process is both effective and efficient in obtaining next-generation sequencing data from a biological sample known to have BKPyV. Urine is the most abundant source of BKPyV in immunocompromised hosts, although the same methods have been successful using plasma from patients with high viremia. This is the first methodology that explains this process and should facilitate the generation of more BKPyV sequence data.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases awards R01 DK125418 to BLL and JTB. Dr. Kleiboeker is an employee of Eurofins Viracor laboratories and performed the initial PCR testing on blood and urine samples free of charge.

Footnotes

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors report no declarations of interest.

References

- Blackard JT, Davies SM, Laskin BL, 2020. BK polyomavirus diversity—why viral variation matters. Rev. Med. Virol 30 10.1002/rmv.2102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Sharp PM, Fowkes M, Kocher O, Joseph JT, Koralnik IJ, 2004. Analysis of 15 novel full-length BK virus sequences from three individuals: evidence of a high intra-strain genetic diversity. J. Gen. Virol 85, 2651–2663. 10.1099/vir.0.79920-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu C, Huang Y, Su J, Wang M, Zhou Q, Zhu B, 2018. The prevalence and isolated subtypes of BK polyomavirus reactivation among patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus-1 in southeastern China. Arch. Virol 163, 1463–1468. 10.1007/s00705-018-3724-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kling CL, Wright AT, Katz SE, McClure GB, Gardner JS, Williams JT, Meinerz NM, Garcea RL, Vanchiere JA, 2012. Dynamics of urinary polyomavirus shedding in healthy adult women. J. Med. Virol 84, 1459–1463. 10.1002/jmv. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kluba J, Linnenweber-Held S, Heim A, Ang AM, Raggub L, Broecker V, Becker JU, Schulz TF, Schwarz A, Ganzenmueller T, 2015. A rolling circle amplification screen for polyomaviruses other than BKPyV in renal transplant recipients confirms high prevalence of urinary JCPyV shedding. Intervirology 58, 88–94. 10.1159/000369210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knowles WA, 2006. Discovery and epidemiology of the human polyomaviruses BK virus (BKV) and JC virus (JCV). In: Ahsan N (Ed.), Polyomaviruses and Human Diseases Springer, New York, New York, NY, pp. 19–45. 10.1007/0-387-32957-9_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laskin BL, Denburg MR, Furth SL, Moatz T, Altrich M, Kleiboeker S, Lutzko C, Zhu X, Blackard JT, Jodele S, Lane A, Wallace G, Dandoy CE, Lake K, Duell A, Litts B, Seif AE, Olson T, Bunin N, Davies SM, 2019. The natural history of BK polyomavirus and the host immune response after stem cell transplantation. Clin. Infect. Dis 1–11. 10.1093/cid/ciz1194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Gibson PE, Knowles WA, Clewley JP, 1993. BK virus antigenic variants: sequence analysis within the capsid VP1 epitope. J. Med. Virol 39 (1), 50–56. 10.1002/jmv.1890390110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo C, Hirsch HH, Kant J, Randhawa P, 2012. VP-1 quasispecies in human infection with polyomavirus BK. J. Med. Virol 84, 152–161. 10.1002/jmv.22147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odegard EA, Meeds HL, Kleiboeker SB, Ziady A, Sabulski A, Jodele S, Davies SM, Laskin BL, Blackard JT, 2021. BK polyomavirus genotypes in two patients after hematopoietic cell transplant. Microbiol. Resour. Announc 10. 10.1128/mra.01122-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pang XL, Martin K, Preiksaitis JK, 2008. The use of unprocessed urine samples for detecting and monitoring BK viruses in renal transplant recipients by a quantitative real-time PCR assay. J. Virol. Methods 149, 118–122. 10.1016/j.jviromet.2007.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peretti A, Geoghegan EM, Pastrana DV, Smola S, Feld P, Sauter M, Lohse S, Ramesh M, Lim ES, Wang D, Borgogna C, FitzGerald PC, Bliskovsky V, Starrett GJ, Law EK, Harris RS, Killian JK, Zhu J, Pineda M, Meltzer PS, Boldorini R, Gariglio M, Buck CB, 2018. Characterization of BK polyomaviruses from kidney transplant recipients suggests a role for APOBEC3 in driving in-host virus evolution. Cell Host Microbe 23, 628–635.e7. 10.1016/j.chom.2018.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rockett R, Barraclough KA, Isbel NM, Dudley KJ, Nissen MD, Sloots TP, Bialasiewicz S, 2015. Specific rolling circle amplification of low-copy human polyomaviruses BKV, HPyV6, HPyV7, TSPyV, and STLPyV. J. Virol. Methods 215–216, 17–21. 10.1016/j.jviromet.2015.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahoo MK, Tan SK, Chen SF, Kapusinszky B, Concepcion KR, Kjelson L, Mallempati K, Farina HM, Fernández-Viña M, Tyan D, Grimm PC, Anderson MW, Concepcion W, Pinskya BA, 2015. Limited variation in BK virus T-cell epitopes revealed by next-generation sequencing. J. Clin. Microbiol 53, 3226–3233. 10.1128/JCM.01385-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suchard MA, Lemey P, Baele G, Ayres DL, Drummond AJ, Rambaut A, 2018. Bayesian phylogenetic and phylodynamic data integration using BEAST 1.10. Virus Evol 4, 1–5. 10.1093/ve/vey016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yogo Y, Sugimoto C, Zhong S, Homma Y, 2009. Evolution of the BK polyomavirus: epidemiological, anthropological and clinical implications. Rev. Med. Virol 10.1002/rmv.613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]