Abstract

Staphylococcus aureus–mediated food poisoning is a primary concern worldwide. The presence of the organism in food is an indicative of poor sanitation during production, and it is essential to have efficient methods for detecting this pathogen. A novel molecular diagnostic technique called loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) serves as a rapid and sensitive detection method, which amplifies nucleic acids at isothermal conditions. In this study, a LAMP-based diagnostic assay was developed to detect Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus) using two target genes femA and arcC. The optimum reaction temperature was found to be 65 °C and at 60 °C for femA and arcC genes, respectively. The developed assay specifically amplified DNA from S. aureus, not from other related bacterial species and compared to PCR, and a 100-fold higher sensitivity was observed. Furthermore, the LAMP assay could detect the pathogen from food samples mainly meat and dairy samples when analyzed in both intact and enriched conditions. Thirteen samples were found positive for S. aureus with LAMP showing a greater number of positive samples in comparison to PCR. This study established a highly sensitive and a rapid diagnostic procedure for the detection and surveillance of this major foodborne pathogen.

Keywords: Foodborne pathogens, LAMP, Staphylococcus aureus, arcC, femA, Genes

Introduction

Foodborne pathogens cause diseases through consumption of contaminated food or water. There are over 250 diseases reported to be caused by bacteria, viruses, and parasites. Outbreaks of foodborne pathogens occur around the world, and two-thirds of the most encountered outbreaks have been linked to bacteria such as Salmonella, Clostridium, and Staphylococcus [1]. More than 3000 deaths are reported every year due to foodborne infections [2, 3]. The process of elimination of microbes is an essential at every step of food production, right from the farm, harvest, food processing, storage, and all the way to the distribution stage [4]. The primary requirement is an effective diagnostic technique followed by surveillance and preventive measures for ensuring food safety. Over the years, the development of nucleic acid-based molecular techniques has made detection and characterization of the pathogens more rapid with greater specificity [5].

Staphylococcus aureus food poisoning is typically associated with consumption of contaminated meat and dairy products. It is frequently isolated from various food samples mainly in dairy, meat, egg, pastries, and sandwich filling products which are high in protein and starch. The organism’s ability to grow at a wide range of temperature and up to 15% NaCl enables it to survive in processed foods. Food poisoning caused by S. aureus serves as one of the most economically important foodborne diseases and is a major issue for public health programs worldwide [6, 7]. The incidence of S. aureus in packed meat and meat products is estimated at 15.7% [8]. The pathogen can be detected by various techniques such as microbiological, biochemical assays, molecular techniques, and immunological assays. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-based methods targeting the enterotoxins; sea, seg, seh, and sei genes; and 23S rDNA have been developed for S. aureus detection [9, 10]. Similarly, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and enzyme-linked fluorescent assay (ELFA) have been used, but these methods lacked sensitivity and specificity [11]. More recently, MALDI-TOF has been used to analyze the proteins produced by the pathogen [12]. However, these techniques are cost intensive and require skilled personnel. Therefore, diagnostic tools, which are cost-effective, specific, and sensitive, are required for the rapid detection of S. aureus. Loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP), a nucleic acid amplification method, has found tremendous applications in the field of diagnosis of infectious diseases, genetic disorders, and genetic traits from the year 2000. This method has overcome many shortcomings of the available molecular methods. The LAMP technique amplifies nucleic acids under isothermal conditions, without the need of thermal cyclers, and thus can be implemented in resource-limited laboratories in developing countries. In LAMP within a short period of time, large quantities of DNA can be synthesized with high specificity [13].

The technique depends on an auto-cycling, strand displacement activity by Bst DNA polymerase, and DNA synthesis with a set of four to six specific primers which recognizes a total of eight distinct sequences on the target DNA and synthesizes many different sizes of DNAs containing several inverted repeats of the target sequence (stem loops). The basic advantage of LAMP is that the technique is a single step process as amplification and detection of the specific gene is completed by incubation at a constant temperature without the requirement of a denaturation step. Simple detection by the naked eye is possible by observing the turbidity derived from the white precipitate of magnesium pyrophosphate, which is generated as a by-product, or under UV light as bright fluorescence derived from calcein in the presence of manganese ions or in real time (every 6 s) by Loopamp Turbidimeter. Here, we describe a LAMP assay targeting femA and arcC, genes specific to the pathogenic S. aureus.

Materials and methods

Bacterial DNA extraction

Standard Staphylococcus aureus strain (ATCC 29,213) was used in the study for optimization of the assay. The culture grown in Luria Bertani broth (LB) (HiMedia Laboratories Pvt. Ltd., India) at 37 °C with continuous shaking overnight was used for genomic DNA extraction following the cetyl trimethyl ammonium bromide (CTAB) method [4].

Primer construction and optimization of LAMP and PCR conditions

A set of four specific primers including two inner primers (FIP and BIP) and two outer primers (F3 and B3) were designed based on the sequence information of the target genes femA (NC_007795.1) and arcC (BX571856.1) using the primer expolorerV4 (http://primerexplorer.jp/elamp4.0.0/index.html) software. The sequence information of the LAMP primers is available on request.

Optimization of LAMP conditions

Genomic DNA isolated from the reference strain was used for optimization of time and temperature of LAMP assays. The LAMP assay was conducted using Loopamp, DNA Amplification kit, (Eiken Chemical Co., Ltd., Japan). Optimization of reaction temperature involved monitoring the reaction at isothermal conditions between 58 and 65 °C. The optimization of the reaction length of LAMP assays was done between 15 and 80 min at the optimum temperature with a 15 min difference between each time point. The assay was carried out in 12.5-µl reaction volume containing 1 µl each of inner primers (40 pmol each), 0.5 µl of F3 and B3, 6.25 µl of 2 × reaction mixture {40 mM TrisHcl, 20 mM Kcl, 16 mM MgSo4, 20 mM (NH4)2SO4, 0.2% tween 20, 1.6 M betaine, 2.8 mM dNTPs each}, 0.5 µl of Bst DNA polymerase, and 1 µl of target DNA and make up the volume with distilled water. The reaction volume of 12.5 µl was prepared and maintained at required isothermal conditions in a dry bath (GeNei, Merck Bioscience, and Bangalore, India). The reaction was terminated by inactivating the enzyme activity at 80 °C for 10 min. The LAMP products were electrophoresed in a 2% agarose gel and visualized using Gel Doc system (Bio-Rad, USA).

Specificity of LAMP assay

To determine the specificity, LAMP assay was carried out using DNA extracted from S. aureus and other closely related gram-positive organisms such as S. epidermidis (ATCC 12,228), Micrococcus luteus (ATCC 9341), Bacillus cereus (ATCC 10,876), Salmonella Typhimurium (ATCC 14,028), Escherichia coli (ATCC 8739), and Listeria monocytogenes (ATCC 35,152).

Sensitivity of LAMP assay

The sensitivity of LAMP assay was determined by using serial dilutions of the initial genomic DNA to obtain the minimum concentration of DNA required for detection. The assay was compared with conventional PCR. A ten-fold serial dilution method was used to determine the minimum concentration of DNA with the initial concentration of DNA at 150 ng/µl. PCR was carried out in 12.5-μl reaction volumes containing 5 μl of dNTP mixture (2.5 mM each of dATP, dCTP, dGTP, and dTTP) and 10 × Gene Taq universal buffer, 0.5 μl of Taq polymerase (5 U μL−1) (HiMedia), 5.0 μl (10 μM) of each primer (target genes: arcC and femA): Fw and Rv, 5.0 μl distilled water, and 1.0 μl DNA. A total of 35 amplification cycles were performed with annealing at 57 °C for femA and 58 °C for arcC for 1 min. The products were electrophoresed on 2% agarose gels and documented using a gel doc system (Bio-Rad, USA).

Screening of Staphylococcus aureus from food samples

The food samples (milk and dairy products, meat samples) were collected in sterile 2.0-ml microcentrifuge tubes (Tarsons Pvt. Ltd, India). One gram or 1 ml of the sample was homogenized in 1 ml Butterfield’s Phosphate buffered dilution water. One hundred microliter of the sample was spread on Baird-Parker agar (BPA) plates and incubated at 37 °C for 48 h. The black-centered colonies with clear zone were further streaked on to LB plates. The isolates were confirmation by Latex agglutination assay which screens for protein A and bound coagulase which are markers for S. aureus (HiMedia, India). The retained samples that were determined as positive by the conventional method were then enriched by inoculating 1 g of sample in 9 ml tryptic soya broth for 12–18 h and the enrichment subjected to crude DNA extraction after 1% Triton X-100 treatment and by boiling for 10 min [14]. The supernatant was used as a template for both LAMP and PCR.

Results

Optimization of LAMP assays for arcC and femA genes

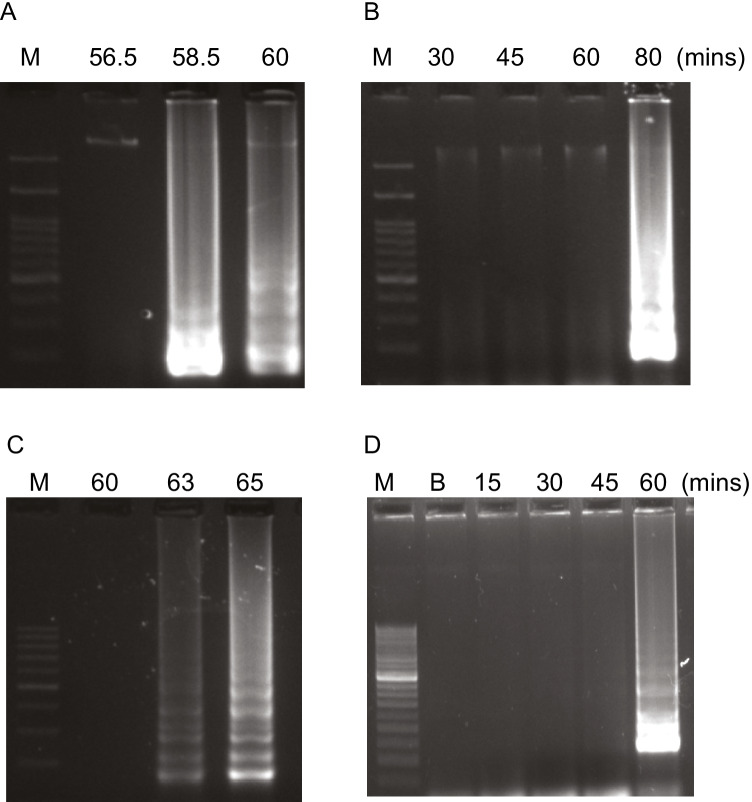

To determine the optimum temperature and time for LAMP using femA and arcC genes, the generation of amplicons was observed at different temperatures and time intervals. Formation of bands was observed at 63 °C and 65 °C for femA gene and at 58.5° C and 60° C for arcC gene. However, 60 °C for 80 min (Fig. 1A and B) and 65° C for 60 min (Fig. 1C and D) were considered as optimum temperature for arcC and femA, respectively, due to the sharpness and clarity of bands.

Fig. 1.

Optimization of time and temperature for LAMP reaction for femA and arcC. A Temperature for femA; lane 1, 60 °C; 2, 63 °C; 3, and 65 °C. B Time for femA; lane 1, blank; 2, 15 min; 3, 30 min; 4, 45 min; and 5, 60 min (C) temperature for arcC gene; and D time for arcC gene. All the products were run on 2.0% agarose gel and stained with ethidium bromide

Specificity of arcC and femA LAMP assays

In order to determine whether the developed assays could specifically identify S. aureus, template DNA obtained from several gram-positive bacteria belonging to other species within the same genus or closely related species within the same family, viz. Staphylococcus epidermidis, Micrococcus luteus, Bacillus cereus, and Listeria monocytogenes, was used for LAMP with arcC and femA genes. As shown in Table 1, positive amplification (formation of multiple stem-loop DNA bands) was seen only in the assays that contained S. aureus DNA indicating the high specificity of the developed assay for detection of S. aureus.

Table 1.

Specificity of LAMP reaction for Staphylococcus aureus

| Target organisms | arc C | femA |

|---|---|---|

| Staphylococcus aureus | + ve | + ve |

| Staphylococcus epidermidis | -ve | -ve |

| Micrococcus luteus | -ve | -ve |

| Listeria monocytogenes | -ve | -ve |

| Bacillus cereus | -ve | -ve |

| Salmonella typhimurium | -ve | -ve |

| Escherichia coli | -ve | -ve |

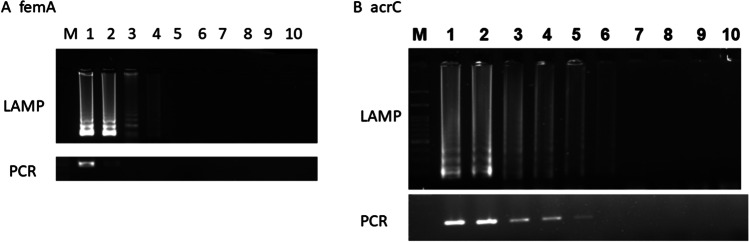

Evaluation of sensitivity of LAMP assay

The sensitivity of the LAMP assays was evaluated by comparing the detection limit of LAMP with that of PCR using tenfold serially diluted template DNA. The initial concentration of DNA used was 150 ng/µl. As shown in Fig. 2A and B, the sensitivity of LAMP was higher than PCR for both arcC and femA genes. In case of femA, the detection limit of LAMP was 100-fold (1.5 pg/μl) higher than that of PCR (15 ng/μl) (Fig. 2A). Similarly, in case of arcC, the detection limit of LAMP was tenfold (1.5 pg/μl) higher than that of PCR (15 pg/μl).

Fig. 2.

Sensitivity of LAMP and PCR reaction for A femA and B arcC with tenfold dilutions of DNA. Lanes: M, 100 bp marker; lane 1, 10 ¯ 1; 2, 10 ¯ 2; 3, 10 ¯ 3; 4, 10 ¯ 4; 5, 10 ¯ 5; 6, 10 ¯ 6; 7, 10¯7; 8, 10 ¯ 8; 9, 10 ¯ 9; 10, 10 ¯ 10. All the products were electrophoresed on 2.0% agarose gel and stained with ethidium bromide

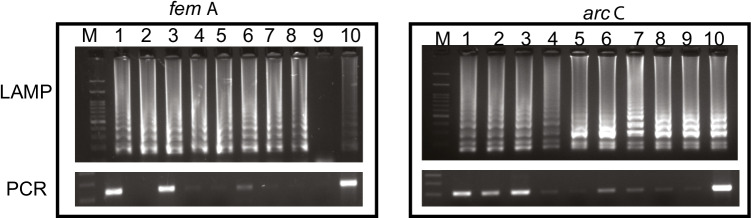

Screening of samples

In order to determine the feasibility of the developed assay as a molecular technique for detection of S. aureus from food samples such as dairy products and meat, random samples were subjected to LAMP assays both in intact and enriched conditions. Out of 36 samples, screened, 13 were positive for S. aureus by the conventional culture method. The enrichment of samples positive by the conventional method were positive for femA and arcC by LAMP indicating the presence of the pathogenic organism in the sample. The number of samples showing the presence of femA and arcC was more in LAMP assay (12/13 and 13/13) when compared to those in PCR (4/13 and 7/13, respectively) (Fig. 3), suggesting an increased sensitivity of the assay using LAMP.

Fig. 3.

Representative image of A LAMP screening of samples for femA and arcC; M, 100 bp marker; lanes 1 and 2, milk samples; lanes 3, 4, 5, 6, and 7, chicken samples; lane 8, mutton sample; lane 9, egg yolk; lane 10, bakery product. B PCR screening of samples for femA and arcC; M, 100 bp marker; lane 1, positive control; 2, milk samples; lanes 3, 4, 5, 6, and 7, chicken samples; lane 8, mutton sample; lane 9, egg yolk; lane 10, bakery product

Discussions

Foodborne illness have been a concern with the rise in incidence of outbreaks every year. Developing countries have visibly higher rates of mortality due to foodborne illness. Staphylococcus aureus is considered as an important human pathogen causing gastroenteritis [1, 13] worldwide. However, many cases remain misdiagnosed and unreported due to the presence of symptoms that indicate similar nature of etiological agents. Nevertheless, it is a major public health concern worldwide. In India, there has been no regular structured surveillance on the various foods involved and the statistical incidence of outbreaks. In a recent pilot study conducted by Ronald Ross Institute of Tropical diseases, Hyderabad, Staphylococcus aureus was found to be the most common etiological agent [15] in food poisoning.

Traditionally, S. aureus is detected through biochemical and immunological parameters, with final confirmation through molecular tests. Over the years, some molecular methods have been developed for S. aureus detection due to the increased sensitivity and the specificity of nucleic acid-based methods. For instance, PCR-based detection of 23S rDNA has proved to be quite effective in identification of the bacterium [16–18]. Similarly, PCR-based detections, both conventional and real-time methods, of Staphylococcus enterotoxins were found to be relatively rapid and a better alternative for the conventional immunological assays [19, 20]. More recently, multiplex PCR that can detect the presence of enterotoxigenic strains has also been developed [21, 22].

In this study, a novel LAMP assay has been developed, which was found to be rapid, highly sensitive, and specific for detection of S. aureus from food samples. Although several LAMP assays have been developed for detection of S. aureus in the last few years, most of these assays were based on genes associated with the antibiotic resistance [23, 24] and have targeted S. aureus associated with clinical infections [25, 26]. However, given the fact that the genes responsible for antibiotic resistance can transfer from one bacterial species to another, assays using such genes might result in false positives. S. aureus causing food infections differ from those that cause other clinical conditions based on the ability of the former to produce enterotoxins. LAMP specific to enterotoxin coding genes has been reported to have better sensitivity than PCR [27]. However, the diversity in the enterotoxin variants of Staphylococcal enterotoxins limits the use of toxin specific detection for food safety [28]. In the present study femA gene, which codes for a cell wall metabolism factor and arcC, which a housekeeping gene was targeted. These genes are specific to the pathogenic strains of S. aureus. The whole process of the LAMP assay from the preparation of DNA template to endpoint detection only required 80 min, whereas the conventional PCR required 4 h starting from DNA template to the visualization of the amplicons using agarose gel electrophoresis. The developed method showed high specificity for S. aureus and was more sensitive than PCR. Even in random food sample screening, isolates that were positive as determined by the latex test for protein A were negative for PCR but gave positive results in LAMP assay, suggesting an increased sensitivity of the developed assay. The culture method requires selective growth on BPA and further confirmation with coagulase. The entire process has a minimum turnover time of 72 h. Microbiological analysis of food samples for S. aureus relies on the confirmation by the coagulase test which further requires the ready availability of highly perishable rabbit plasma While direct analysis of food sample is rapid, studies have shown that sensitive methods like LAMP require a minimum of 100 CFU/g of sample [27]. Statutory microbiological standards require a complete absence of S. aureus in food and hence conventional culture techniques though time-consuming are the gold standard. The method developed herein provides an initial enrichment step which caters to ensuring the availability of minimum number of cells for detection by LAMP. Thus, the developed methods can specifically detect S. aureus in the food samples within 24 h of sample receipt and yet provide the sensitivity of detecting as low as 1 CFU/g of sample. Additionally, the LAMP-based method can detect viable but non-culturable forms that can still cause infection but are not detected by the conventional culture method [29].

The developed assay could be adapted as the standard detection technique by virtue of easefulness in screening of food samples. This assay could be further developed as a point of care device for routine screening of suspected samples, particularly during outbreaks. The developed assay can pave the way for more specific methods to detect enterotoxin producing strains as cases of coagulase-negative enterotoxigenic staphylococci have recently come to the attention of food safety. Inclusion of dye-based methods of detection can aid in rapid visual analysis and avoid the additional step of agarose gel electrophoresis [30].

The primers used in this study are highly specific for S. aureus as closely related species S. epidermidis was not detected. The objective of this study was to develop a rapid method for the detection of S. aureus in food. While our study proves that initial enrichment provides better results than direct detection from sample, its applicability for routine food testing can be ascertained after testing the method for a sufficient sample size for each different food matrix.

Conclusion

In summary, the developed LAMP assay targeting femA and acrC could be used for rapid detection and screening technique of Staphylococcus aureus in food samples. The sensitivity of the assay was found to be 100-fold higher than conventional PCR. The specificity of the assay is an important criterion while developing a technique for accurate identification of a pathogen; the developed assay was found to be very specific for Staphylococcus aureus. Thus, assay could be further developed as a point of care device for routine screening of suspected samples, particularly during outbreaks.

There is no denying the fact that non-specific amplification is one of the major issues in LAMP technique. However, this limitation can be overcome by standardizing the primer and buffer concentrations. Currently, many automated LAMP devices are commercially available as powerful alternatives for accurate and quick identification of pathogens in different fields of research.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the Department of Science and Technology (DST), Government of India for providing the fund under women Scientist Scheme (WOS-A): SR/WOS-A/LS-1065/2014 (G). The corresponding author also sincerely acknowledged Prof. Dr. Indrani Karunasagar for her constant guidance throughout the project.

Author contribution

MH: conducts the research and investigation process, specifically performing the experiments, or data collection, and manuscript preparation.

RV: conducts the research and investigation process.

JMR: experiments design and conducts the research and investigation process and manuscript preparation.

GC: conceptualization of the research design, funding acquisition, and manuscript preparation and supervision of the research.

Funding

Women Scientist Scheme (WOS-A): SR/WOS-A/LS-1065/2014 (G). Department of Science and Technology (DST), Government of India.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Responsible Editor: Luis Augusto Nero

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Le Loir Y, Baron F, Gautier M. Staphylococcus aureus and food poisoning. Genet Mol Res. 2003;2(1):63–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mead PS, Slutsker L, Dietz V, McCaig LF, Bresee JS, Shapiro C, Griffin PM, Tauxe RV. Food-related illness and death in the United States.". Emerg Infect Dis. 1999;5(5):607. doi: 10.3201/eid0505.990502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.De Boer E, Zwartkruis-Nahuis JT, Wit B, Huijsdens XW, De Neeling AJ, Bosch T, Van Oosterom RA, Vila A, Heuvelink AE. Prevalence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in meat. Int J Food Microbiol. 2011;134:52–56. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2008.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ausubel FM, Kingston R, Moore RE, Seidman DD, Smith, J G JA, Struhl K, Ferreira Behravesh CB, Williams, IT, Tauxe RV (2012) Emerging foodborne pathogens and problems: expanding prevention efforts before slaughter or harvest. Improving Food Safety through a One Health Approach Workshop Summary.

- 5.Dwivedi HP, Jaykus LA. Detection of pathogens in foods: the current state-of-the-art and future directions. Crit Rev Microbiol. 2011;37:40–63. doi: 10.3109/1040841X.2010.506430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alarcon B, Vicedo B, Aznar R. PCR-based procedures for detection and quantification of Staphylococcus aureus and their application in food. J Appl Microbiol. 2006;2:352–364. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2005.02768.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Su J, Liu X, Cu H, Li Y, Chen D, Li Y, Yu G. Rapid and simple detection of methicillin-resistance staphylococcus aureus by orfX loop-mediated isothermal amplification assay. BMC Biotechnol. 2014;14:8. doi: 10.1186/1472-6750-14-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rodríguez-Lázaro D, Oniciuc EA, García PG, Gallego D, Fernández-Natal I, Dominguez-Gil M, Eiros-Bouza JM, Wagner M, Nicolau AI, Hernández M. Detection and characterization of Staphylococcus aureus and methicillin-resistant S aureus in foods confiscated in EU borders. Frontiers in microbiology. 2017;8:1344. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.01344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pereira V, Lopes C, Castro A, Silva J, Gibbs P, Teixeira P. Characterization for enterotoxin production, virulence factors, and antibiotic susceptibility of Staphylococcus aureus isolates from various foods in Portugal. Food Microbiol. 2009;26(3):278–282. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2008.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goto M, Hayashidani H, Takatori K, Hara-Kudo Y. Rapid detection of enterotoxigenic Staphylococcus aureus harbouring genes for four classical enterotoxins, SEA, SEB, SEC and SED, by loop-mediated isothermal amplification assay. Lett Appl Microbiol. 2007;45:100–107. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765X.2007.02142.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Byrne B, Gilmartin N, Lakshmanan RS, O’Kennedy R (2015) Antibodies, enzymes, and nucleic acid sensors for high throughput screening of microbes and toxins in food. High throughput screening for food safety assessment: 25–80.

- 12.Hennekinne JA, De Buyser ML, Dragacci S. Staphylococcus aureus and its food poisoning toxins: characterization and outbreak investigation. FEMS microbiology reviews. 2012;36:815–836. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2011.00311.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tomita N, Mori Y, Kanda H, Notomi T. Loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) of gene sequences and simple visual detection of products. Nat Protoc. 2008;3:877–882. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sowmya N, Thakur MS, Manonmani HK. Rapid and simple DNA extraction method for the detection of enterotoxigenic Staphylococcus aureus directly from food samples: comparison of PCR and LAMP methods. Journal of applied microbiology. 2012;113:106–113. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2012.05315.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shriver-Lake LC, Shubin YS, Ligler FS. Detection of staphylococcal enterotoxin B in spiked food samples. J Food Prot. 2003;66:1851–1856. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X-66.10.1851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sudershan RV, Naveen Kumar R, Kashinath L, Bhaskar V, Polasa K (2014) Foodborne infections and intoxications in Hyderabad India. Epidemiology Research International, 2014.

- 17.Straub TM, Chandler DP. Towards a unified system for detecting waterborne pathogens. J Microbiol Methods. 2003;53:185–197. doi: 10.1016/S0167-7012(03)00023-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koreen L, Ramaswamy SV, Graviss EA, Naidich S, Musser JM, Kreiswirth BN. spa typing method for discriminating among Staphylococcus aureus isolates: implications for use of a single marker to detect genetic micro-and macro variation. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42:792–799. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.2.792-799.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Girish PS, Anjaneyulu ASR, Viswas KN, Shivakumar BM, Anand M, Patel M, Sharma B. Meat species identification by polymerase chain reaction-restriction fragment length polymorphism (PCR-RFLP) of mitochondrial 12S rRNA gene. Meat Sci. 2005;70:107–112. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2004.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johnson WM, Tyler SD, Ewan EP, Ashton FE, Pollard DR, Rozee KR. Detection of genes for enterotoxins, exfoliative toxins, and toxic shock syndrome toxin 1 in Staphylococcus aureus by the polymerase chain reaction. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;29(3):426–430. doi: 10.1128/jcm.29.3.426-430.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Omoe K, Ishikawa M, Shimoda Y, Hu DL, Ueda S, Shinagawa K. Detection of seg, seh, and sei genes in Staphylococcus aureus isolates and determination of the enterotoxin productivities of S. aureus isolates harbouring seg, seh, or sei genes. J Clin Microbiol. 2002;40:857–862. doi: 10.1128/JCM.40.3.857-862.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pereira V, Lopes C, Castro A, Silva J, Gibbs P, Teixeira P. Characterization for enterotoxin production, virulence factors, and antibiotic susceptibility of Staphylococcus aureus isolates from various foods in Portugal. Food Microbiol. 2009;26:278–282. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2008.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang T, Wang C, Wei X, Zhao X, Zhong X (2012) Loop-mediated isothermal amplification for detection of Staphylococcus aureus in dairy cow suffering from mastitis. Journal of Biomedicine and Biotechnology: 435982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Su J, Liu X, Cui H, Li Y, Chen D, Li Y, Yu G. Rapid and simple detection of methicillin-resistance staphylococcus aureus by orfX loop-mediated isothermal amplification assay. BMC Biotechnol. 2014;14:8. doi: 10.1186/1472-6750-14-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Koide Y, Maeda H, Yamabe K, Naruishi K, Yamamoto T, Kokeguchi S, Takashiba S. Rapid detection of mecA and spa by the loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) method. Lett Appl Microbiol. 2010;50(4):386–392. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765X.2010.02806.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen C, Zhao Q, Guo J, Li Y, Chen Q. Identification of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) using simultaneous detection of mecA. nuc. and femB by loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) Curr Microbiol. 2017;74(8):965–971. doi: 10.1007/s00284-017-1274-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sowmya N, Thakur M, Manonmani H. Rapid and simple DNA extraction method for the detection of enterotoxigenic Staphylococcus aureus directly from food samples: comparison of PCR and LAMP methods. J Appl Microbiol. 2012;113:106–113. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2012.05315.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hu DL, Li S, Fang R, Ono HK. Update on molecular diversity and multipathogenicity of staphylococcal superantigen toxins. Animal Diseases. 2021;1:7. doi: 10.1186/s44149-021-00007-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li Y, Yang L, Fu J, Yan M, Chen D, Zhang L. The novel loop-mediated isothermal amplification based confirmation methodology on the bacteria in Viable but Non-Culturable (VBNC) state. Microb Pathog. 2017;111:280–284. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2017.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pang B, Yao S, Xu K, Wang J, Song X, Mu Y, Zhao C, Li J. A novel visual-mixed-dye for LAMP and its application in the detection of foodborne pathogens. Anal Biochem. 2019;574:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2019.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]