Abstract

Objectives

The aim of this study is to develop and validate a scale to measure provider attitudes towards provision of youth-friendly sexual and reproductive health (SRH) services in a conservative setting in the Middle East.

Design

Cross-sectional, psychometric validation study.

Setting

Public health facilities in Amman, Irbid, Mafraq and Zarqa in Jordan.

Participants

552 healthcare providers were recruited by convenience. Providers were eligible if they were a practising midwife, nurse or physician in one of the selected health facilities.

Methods

An initial pool of 52 items was generated using theory and local expert input. We evaluated the psychometric properties of the scale using factor analysis. We assessed internal consistency reliability by calculating Cronbach’s alpha and convergent construct validity using linear regression to assess the association between a provider’s score on the scale and whether they had ever received training on SRH issues.

Results

Our final scale consisted of 3 dimensions and 29 items corresponding to the constructs of: (1) Attitudes towards Information and Services Offered to Youth (11 items) (2) norms and personal beliefs (10 items) and (3) attitudes towards the service delivery environment (8 items). Cronbach’s alpha was estimated at 0.72 for the full scale, and between 0.70 and 0.73 for each subscale. The scale demonstrated high construct validity. The results of the linear regression analysis suggest that respondents who had received SRH training had a mean score that was 16% higher (0.64 points; 95% CI 0.2 to 11.2; p<0.01) on the full attitudes scale compared with those who did not.

Conclusions

This paper describes a study to formally develop and validate a scale to measure healthcare provider attitudes in support of youth-friendly SRH services, thus providing an important tool to identify areas for improvement of youth SRH programmes in the Middle East and globally.

Keywords: health policy, sexual medicine, quality in health care, reproductive medicine

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Scale items were generated through a participatory process engaging local and international experts.

The scale underwent a assessment of several forms of validity and reliability using a large sample of healthcare providers.

The purpose of this paper is to develop and validate a scale, rather than to describe provider attitudes using a generalisable sample of providers in Jordan.

While the scale items may be adapted to other contexts, items were developed to focus on the adolescent sexual and reproductive health priorities in the Middle East.

Background

Despite increased global attention focused on the sexual and reproductive health (SRH) needs of youth, youth continue to comprise an important population whose SRH needs are often overlooked.1 Issues such as sexual and gender-based violence, prevention of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and unintended pregnancy, access to contraception and safe abortion remain important priorities for youth throughout the world. Many of the SRH concerns that affect youth are exacerbated by social and cultural norms and other economic and policy constraints that restrict access to SRH information and services.

A number of the barriers that prevent youth from obtaining SRH services exist within the health service delivery environment. In some cases, the attitudes and practices of health service providers may deter youth from accessing and utilising SRH services.2 3 Youth may be afraid to approach health service providers in fear of judgmental attitudes, disrespect or stigmatisation, poor quality of care and breaches of confidentiality.4–6 Providers may also unnecessarily restrict access to SRH services to youth by requiring parental or spousal permission where it is not required, refusing to provide services based on their own personal moral or religious beliefs, or enforcing non-existent or misunderstood policies or laws pertaining to the provision of specific services based on age, parity or marital status.6–9

Reorienting health services to be youth-friendly is one strategy that has been shown to improve SRH service utilisation among youth.9 10 Youth-friendly SRH services are those that attract youth, provide a comfortable and appropriate setting for youth, meet the service delivery needs of youth and retain their youth clientele through follow-up visits.11 The WHO defines youth-friendly services within a quality of care framework that focuses on whether services provided to youth are accessible (youth are able to obtain existing services), acceptable (youth are willing to obtain existing services), equitable (all youth are able to obtain services), appropriate (the correct services are provided to youth) and effective (the correct services are provided in a correct way).12 Tylee et al further operationalise WHO’s youth-friendly criteria13 and identify several attributes of youth-friendly services that relate specifically to providers with an emphasis on ensuring quality and respectful service delivery.14 In a systematic review of indicators related to youth-friendly healthcare, staff attitudes, such as those related to respect and friendliness, emerged as a universally applicable concern and an important area to consider when measuring whether services offered are youth-friendly.15

Despite the important role that providers play in ensuring that SRH services are youth-friendly, there has been little consistency in measuring provider attitudes towards the provision of youth-friendly SRH services across studies,16 and the majority of other studies are narrow in scope and have important methodological limitations. The majority of studies that have sought to measure provider attitudes towards youth-friendly services focus on specific health topics such as post-abortion care or contraception,17 use only a few items,18 19 or use qualitative methodologies.20 As a result, they may not provide a comprehensive picture or be broadly applicable to a variety of country or programmatic settings. Three studies conducted in Ethiopia, Nigeria, Zambia and Kenya employ multi-item scales;5 21 22 however, they do not provide details as to whether the scales were developed and validated according to established psychometric methods.

SRH issues among youth have been identified as a national priority in Jordan; however, the provision of youth-friendly SRH services remains nascent and health services are underutilised by youth. The 2005–2009 National Youth Strategy focused on improving reproductive health services for youth, especially through information dissemination, premarital medical examination, and the provision of youth-friendly services,23 however, the policy lacks indicators and a well-defined monitoring strategy. Measuring provider attitudes towards the provision of youth friendly services is therefore critical to meeting Jordan’s stated policy objectives and improving SRH service utilisation among youth. Past research has shown that youth often find existing SRH services unpleasant, inadequate and unprofessional; health service providers do not take youth’s concerns seriously, and that youth report negative experiences with SRH services.24 25 Despite there being a strong demand for youth-friendly services,24 no studies to date have focused expressly on the service providers themselves in this context.26 As such, the purpose of this study is to describe the development and psychometric validation of a scale to measure provider attitudes in support of youth-friendly SRH services that is applicable within Jordan and in other countries across the Middle East.

Methods

Research aim

Our overall research aim is to develop and validate a scale to measure provider attitudes in relation to the delivery of youth-friendly SRH services. Our target population is considered to be generalist providers that are most likely to encounter youth seeking SRH services: nurses, midwives, and primary care physicians. The measurement properties of interest focus on the target population’s attitudes towards the services provided to youth between the ages of 15–24, including youth who are both married and unmarried, as well as both men and women. To do this, we followed a standard, multistep process including item generation, data collection and factor analysis, which is described in detail in the following sections.

Scale development and data collection took place between August 2018 and August 2019.

Patient and public involvement

We involved a group of eight external key informants, including government representatives, academics, service providers and youth advocates in the development of our study tools as described in the sections below.

Scale item generation

To develop the initial set of items to include in the scale, we followed standard procedures to ensure content validity. Content validity refers to whether the items in a scale are relevant to and fully representative of the target construct and its domains.27 Our process included the following steps: (1) we conducted a literature review to define the construct of provider attitudes in support of youth-friendly SRH services and identify relevant domains, (2) we extracted relevant items from existing scales that were retrieved from our search and (3) we engaged local and international experts to assess content validity and to ensure that the items in the scale were contextually relevant.28 To conduct our literature review, we searched PubMed and scanned references of retrieved and relevant documents. Search terms used included ‘adolescent,’ ‘youth,’ ‘teen,’ ‘health services,’ ‘healthcare,’ ‘health delivery,’ ‘youth-friendly,’ ‘reproductive health’ and ‘sexual health.’

In the first step, we derived 40 statements related to attitudes towards service provision from the literature review to correspond with the theoretical constructs in relation to the five domains identified by WHO to characterise youth-friendly health services: accessibility (eg, ‘Schools and health facilities should work together to provide reproductive health information and services to youth’), acceptability (eg, ‘Youth should be given the same level of confidentiality when receiving sexual and reproductive health services as adults’), equity (eg, ‘Reproductive health services are not necessary for boys’), appropriateness (eg, ‘If a young woman says that she has experienced sexual or gender-based violence, I will call official institutions to help her’) and effectiveness (eg, ‘I am not trained to address the reproductive health needs of youth’). We included all items that corresponded to these domains. Statements focused on SRH topics of both international and local importance, such as sexual and gender-based violence, family planning and contraception, sexuality, reproductive infections, and puberty, and included questions about married and unmarried youth.

In the second step, the scale consisting of the original forty statements was presented to a group of eight local and two international experts in the field of youth SRH. Experts were identified as individuals who were involved in youth health service delivery programme and policy within the local context, and included government officials at relevant ministries, representatives from international donor organisations, and local programmatic stakeholders from health service delivery organisations, and were selected by convenience and interest in the study. These experts consisted of Jordanian key informants, including government representatives, academics, service providers and youth advocates, participated in an interactive consultation in which they were instructed to critique, edit and add to the pool of statements. After this initial review, we again distributed the expanded list of items to the key informants to serve as expert judges to independently assess whether the items were appropriate, accurate and interpretable.29 We used the judgement method to determine whether items should be accepted, rejected or modified based on majority opinion.30

Survey questions were translated from English to Arabic then back to English to ensure proper translation of key ideas. Two international experts then reviewed the suggested changes to ensure clarity of all items. No items were removed at this stage. From this review, 12 items were added, for a total of 52 statements. Responses to each statement in the scale ranged from 1 (‘strongly disagree’) to 4 (‘strongly agree’). Table 1 provides the original 52 items included in the scale as well as their relationship to the original domains of accessibility, acceptability, equity, appropriateness and effectiveness. The final survey instrument is available as online supplemenal file 1.

Table 1.

Original 52 items generated in scale development and their theoretical orientation

| Scale item | Youth-friendly domain | |

| 1 | Unmarried adolescents seeking sexual and reproductive health services should be told to abstain when they ask for contraceptives | Appropriateness, equity |

| 2 | If a girl asks me a question about sex, I should answer the question honestly | Effectiveness |

| 3 | Adolescent boys should be taught that masturbation is dangerous | Appropriateness |

| 4 | Healthcare providers should pressure on clients to make them admit that they have been a victim of sexual or gender-based violence | Effectiveness |

| 5 | Boys and girls should not be given information about puberty because it will encourage them to engage in sexual behaviour | Acceptability, appropriateness |

| 6 | Only girls should be given information about sexual and reproductive health because they are the ones who have the most issues related to sexual behaviour | Equity |

| 7 | Discussing sexual intercourse with unmarried women and men is shameful | Acceptability, equitable |

| 8 | Unmarried youth should never be asked about reproductive health concerns because they are not sexually active | Effectiveness, equitable |

| 9 | If a girl has irregular periods, I will suspect she is sexually active | Acceptability |

| 10 | The best way to prevent unmarried adolescents from becoming sexually active is to keep them in the dark about these issues | Acceptability |

| 11 | Educating youth on reproductive health topics leads to sexual immorality | Acceptability |

| 12 | Youth who are out of school are more likely to be sexually promiscuous than youth in school | Acceptability |

| 13 | If a boy or a girl has a genital ulcer, it is because he or she is promiscuous | Acceptability |

| 14 | If a girl has irregular periods, her parents should be informed | Acceptability |

| 15 | I would feel comfortable counselling a young man showing symptoms of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) | Effectiveness |

| 16 | I would feel comfortable treating an unmarried girl with an ovarian cyst | Effectiveness |

| 17 | I would treat an unmarried woman showing symptoms of STIs without judging her | Acceptability |

| 18 | Contraceptives should not be given to young women who suffer reproductive health issues because it will negatively affect their future fertility | Equity, effectiveness |

| 19 | Girls should not receive any information about contraceptives before they are married because it will cause them to become sexually active. | Equitable, appropriateness |

| 20 | Asking youth if they are victims of any kind of violence is considered interfering with their personal or family issues | Appropriateness |

| 21 | Boys should be taught how to use a condom | Appropriateness |

| 22 | Unmarried adolescents should not be provided with contraceptives because culture and religion prohibit engagement in premarital sex | Equity, acceptability |

| 23 | Youth should learn about contraceptives before marriage | Appropriateness |

| 24 | Teaching unmarried youth about contraceptives is acceptable | Appropriateness |

| 25 | Healthcare providers should provide both married and unmarried adolescents with contraceptives if they ask for them | Equity |

| 26 | An unmarried girl should never be given contraceptives to treat menstrual cramps or irregular periods | Effectiveness |

| 27 | If a boy asks for condoms, it shows responsibility | Acceptability |

| 28 | I feel comfortable providing adolescent girls with contraceptives for any reason | Effectiveness |

| 29 | In my culture, it is wrong for adolescents to use contraceptives | Acceptability |

| 30 | I would scold an unmarried adolescent if he or she asks for contraceptives | Acceptability |

| 31 | I would refuse to provide contraceptives for adolescents before marriage. | Effectiveness |

| 32 | Parents should be informed if their unmarried daughters come to a health facility to seek reproductive health services | Acceptability |

| 33 | Youth should be given the same level of confidentiality when receiving sexual and reproductive health services as adults | Acceptability |

| 34 | Reproductive health services are not necessary for boys. | Equity |

| 35 | The concerns that youth have regarding reproductive health are not important | Acceptability |

| 36 | Reproductive health services are only available for married women | Equity |

| 37 | If a young woman comes into a health facility and says she has been the victim of sexual assault, she probably did something to deserve it. | Acceptability |

| 38 | Women and men of all ages should be welcomed into the clinic for sexual and reproductive health services if they seek them | Accessibility, equity |

| 39 | Parents need to provide permission for their daughters to receive any reproductive health services | Accessibility |

| 40 | It is important to make sure that any services provided to youth are done so privately so no one else in the clinic can hear | Acceptability |

| 41 | Educational materials on sexual and reproductive health should be openly available to unmarried boys and girls | Accessibility |

| 42 | Schools and health facilities should work together to provide reproductive health information and services to youth | Accessibility |

| 43 | If a young woman says that she has experienced sexual or gender-based violence, I will call official institutions to help her | Appropriateness |

| 44 | My personal beliefs guide the way I provide health services to adolescents | Effectiveness |

| 45 | My religion supports the provision of sexual and reproductive health information and services to youth, regardless of their marital status | Effectiveness, equity |

| 46 | I am afraid that I would be punished if I provide any reproductive health services to unmarried adolescents | Effectiveness |

| 47 | I am not trained to address the reproductive health needs of youth | Effectiveness |

| 48 | Health workers play an important role in reducing sexual and reproductive health problems among premarital adolescents | Acceptability, equity |

| 49 | I would feel annoyed if a young, unmarried woman came to me with symptoms of induced abortion | Acceptability |

| 50 | Sexual and gender-based violence among youth should receive governmental attention as a significant social issue | Accessibility |

| 51 | If a client does not volunteer information to me that they have been subject to violence perpetrated by members of their family, I shouldn’t ask them directly about it because it is none of my business. | Appropriateness |

| 52 | By definition, boys cannot be the victims of sexual assault | Equity |

bmjopen-2021-052118supp001.pdf (100.7KB, pdf)

Scale validation

Our process for validating the scale consisted of a multistep process, as described in detail below. First, we collected primary data from healthcare providers. Second, we used the data collected to perform a psychometric evaluation of the properties of the scale.

To collect data from health service providers, we administered the original 52-item scale to a sample of 582 healthcare providers practicing in primary care health centres and maternal child health centres located in Amman, Irbid, Mafraq and Zarqa. The survey was administered individually, via pen and paper, to reduce potential bias related to the sensitivity of the topic.

We used a two-stage cluster sampling scheme to identify participants in the study. In the first stage, we randomly selected health facilities in the four governorates included in the study. In the second stage, we recruited primary care physicians, midwives and nurses working in each selected facility by convenience. All primary care physicians, midwives and nurses working at the facility at the time of recruitment were eligible to participate.

The following equation was calculate the per-governorate sample size that incorporates the design effect to account for clustering in the data:

where: N=required sample

t=value of confidence level

p=estimated prevalence of the indicator of interest

m=margin of error

Deff=intracluster correlation.

To calculate the sample required, we used a 95% CI and a margin of error of 0.1. To maximise the required sample size, we assumed the prevalence (p) of youth-friendly attitudes was 0.5, as the true value is unknown. Further, we assumed an intra-cluster correlation within facilities of 1.2.31 We arrived at a required sample size of 116 per governorate, and a total minimum sample of 464 providers needed for the study.

Analysis

To assess the psychometric properties of the scale using the primary data collected, we began by using an iterative analysis process using exploratory factor analysis to reduce the dimensionality of the data. Factor analysis simplifies the data by identifying the number of latent dimensions needed to account for the common variance of the items in the scale.32 Stata V.14.0 was used for all statistical analyses.33

To prepare the data for factor analysis, we reverse-coded any items that were worded negatively and examined the distribution of each item and patterns of missing responses. We used a combination of case-wise deletion of individuals missing items and mean imputation. Both of these approaches are common in multivariate analysis using survey responses with missing data,34 as factor analysis can only be completed on complete matrices.35 We first excluded individuals who had missing responses to more than two questions (n=30). We then used mean imputation to substitute missing responses with the scale mean for individuals who were missing responses to 1 (n=123) or 2 (n=43) survey questions. To ensure that our results were robust, we later performed a sensitivity analysis using only the 386 complete cases and compared the results to ensure no substantial differences in findings.34 To ensure that our sample contained sufficient common variance to perform exploratory factor analysis, we calculated the Keiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) Measure of Sampling Adequacy.36 KMO values above 0.60 are considered to be adequate to perform exploratory factor analysis.37

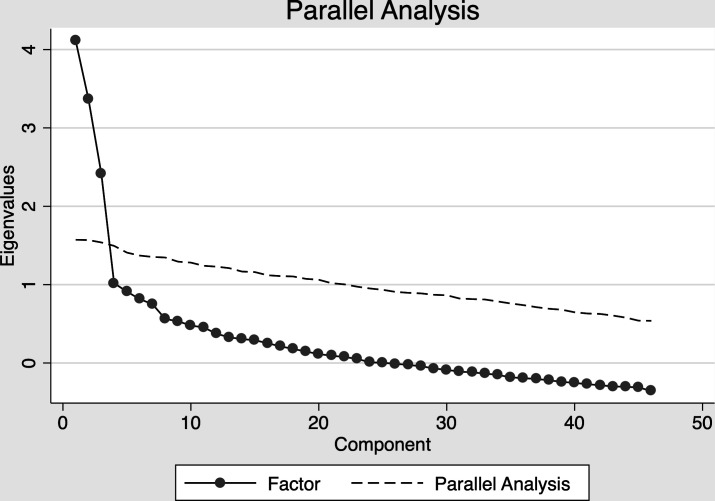

To conduct the factor analysis, we first determined the underlying factor structure by drawing on several accepted analytical approaches as well as underlying theory.38 We first examined the Eigenvalues (which is a measure of how much variance is explained by the factor) and the scree plot resulting from an initial factor analysis. Kaiser’s criterion suggests that factors with Eigenvalues greater than one are retained.39 We then generated a scree plot to plot the relationship between the number of factors and the Eigenvalues. The number of factors to retain corresponds with the point at which the curve forms an ‘elbow,’ or levels off into a linear trend.28 Last, we conducted a parallel analysis, which provides insight into the maximum number of factors to retain in the model based on comparing the data with randomly generated datasets.40 41 It should be noted, however, that exploratory factor analysis is a process that uses a combination of empirical and subjective approaches,42 and interpretability of the factors retained is the ultimate criterion.32 Thus, we used this process iteratively and at each step we focused on the conceptual interpretability of the results.

After factor extraction, we rotated the factors using oblique rotation. Factor rotation orients the factor pattern to an interpretable position that facilitates interpretation by maximising a criterion known as simple structure, whereby items exhibit high loadings on one or two factors and low loadings on the remaining factors.32 43 We chose to use oblique rotation as it allows the factors to be correlated38 given there is overlap with regard to the domains related to provider attitudes in support of youth-friendly SRH services. We retained factors with loadings greater than 0.3.44 45

Using the final scale, we assessed internal consistency reliability by calculating Cronbach’s alpha,46 which relates to how well the items in a scale measure the same underlying construct.47 Cronbach’s alpha ranges from 0 to 1 with a higher score implying greater reliability. Alpha higher than 0.7 is typically considered to be good, while an alpha higher than 0.90 may indicate redundancy among some items as.28 38 48 49 As per best practices in scale development, we examined any item for deletion that did not improve the scale’s internal consistency reliability.38

Criterion validity relates to whether the measure is related to some criterion or ‘gold standard’ by which the phenomenon of interest is typically measured.28 In the absence of a ‘gold standard,’ researchers focus on establishing construct validity through empirical assessments to examine the relationship between the scale and a variable that is theoretically believed to share a similar relationship to the underlying construct.45 50 Construct validity explores the degree to which the measure sufficiently represents the intended concept by examining its theoretical relationship with other variables; in other words, it assesses whether the measure=behaves in the way it should behave with regard to other established measures.28 As there is no ‘gold standard’ by which to measure provider attitudes in support of youth-friendly SRH services, we assess convergent construct validity through linear regression to assess the association between whether a respondent had ever been specifically trained in SRH issues and their mean score for the full scale and each subscale. Training on SRH issues has been found to be associated with youth-friendly attitudes in other settings.5 We hypothesised that individuals who had received training on SRH issues would be more likely to espouse more supportive attitudes towards youth-friendly SRH services.

Results

Characteristics of the study population

The characteristics of the study population are described in table 2. The majority of respondents were between the ages of 25–35 years (58.2%), female (77.4%), nurses (50.9%) and had received SRH training in the past (69.8%).

Table 2.

Descriptive characteristics of healthcare providers, their background in SRH service provision, and the healthcare facility

| Sample characteristics | % (n) |

| Age | |

| 18–24 years | 8.35 (46) |

| 25–35 years | 50.09 (276) |

| 36–45 years | 27.40 (151) |

| 46+years | 13.97 (77) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 19.20 (106) |

| Female | 80.80 (446) |

| Religion | |

| Muslim | 98.73 (545) |

| Christian | 1.27 (7) |

| Governorate | |

| Amman | 40.04 (221) |

| Irbid | 19.75 (109) |

| Mafraq | 21.56 (119) |

| Zarqa | 18.66 (103) |

| Facility type | |

| Maternal child health centre | 43.4 (23) |

| Primary/comprehensive care centre | 54.72 (29) |

| No answer | 1.9 (1) |

| Provider type | |

| Midwife | 36.93 (202) |

| Nurse | 42.60 (233) |

| Primary physician | 20.29 (111) |

| Length of practice | |

| Less than 5 years | 26.74 (146) |

| 5–10 years | 28.75 (157) |

| 11–20 years | 32.42 (177) |

| 20+ years | 12.09 (66) |

| Had SRH training | |

| Yes | 61.72 (337) |

| No | 38.10 (208) |

SRH, sexual and reproductive health.

Results from psychometric validation

The examination of the parallel analysis plot and eigenvalues supported a three-factor solution. The results from the parallel analysis are provided in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Results from parallel analysis with the original scale items.

Our final scale consisted of 3 dimensions and 29 items which corresponded to the underlying constructs of: (1) ‘Attitudes towards Information and Services Offered to Youth’ (11 items), (2) ‘Norms and Personal Beliefs’ (10 items) and (3) ‘Attitudes towards the Service Delivery Environment’ (eight items). The final three-factor solution explains 89% of the total variance of the items in the scale. The factor loadings for each item retained in the scale and their subscale assignment are provided in table 3.

Table 3.

Final factor loadings and subscales for each item retained in the final provider attitudes towards youth-friendly services scale

| Statement | Factor loadings | |||

| Dimension 1 | Dimension 2 | Dimension 3 | ||

| Subscale 1: Attitudes towards information and services offered to youth | ||||

| 1 | Unmarried adolescents seeking sexual and reproductive health services should be told to abstain when they ask for contraceptives | 0.34* | −0.02 | −0.09 |

| 7 | Discussing sexual intercourse with unmarried women and men is shameful | 0.31* | 0.12 | 0.20 |

| 21 | Boys should be taught how to use a condom | 0.33* | −0.31 | 0.22 |

| 22 | Unmarried adolescents should not be provided with contraceptives because culture and religion prohibit engagement in premarital sex | 0.48* | 0.03 | −0.08 |

| 28 | I feel comfortable providing adolescent girls with contraceptives for any reason | 0.35* | −0.38 | 0.23 |

| 29 | In my culture, it is wrong for adolescents to use contraceptives | 0.40* | −0.02 | −0.12 |

| 30 | I would scold an unmarried adolescent if he or she asks for contraceptives | 0.59* | 0.09 | 0.06 |

| 31 | I would refuse to provide contraceptives for adolescents before marriage | 0.64* | 0.03 | 0.13 |

| 32 | Parents should be informed if their unmarried daughters come to a health facility to seek reproductive health services | 0.41* | 0.07 | −0.02 |

| 36 | Reproductive health services are only available for married women | 0.39* | 0.15 | 0.19 |

| 49 | I would feel annoyed if a young, unmarried woman came to me with symptoms of induced abortion | 0.44* | −0.07 | −0.21 |

| Subscale 2: Norms and personal beliefs | ||||

| 5 | Boys and girls should not be given information about puberty because it will encourage them to engage in sexual behaviour | 0.03 | 0.42* | 0.03 |

| 6 | Only girls should be given information about sexual and reproductive health because they are the ones who have the most issues related to sexual behaviour | 0.11 | 0.36* | −0.06 |

| 10 | The best way to prevent unmarried adolescents from becoming sexually active is to keep them in the dark about these issues | 0.08 | 0.48* | 0.13 |

| 11 | Educating youth on reproductive health topics leads to sexual immorality | 0.13 | 0.54* | 0.17 |

| 13 | If a boy or a girl has a genital ulcer, it is because he or she is promiscuous | 0.00 | 0.42* | −0.06 |

| 20 | Asking youth if they are victims of any kind of violence is considered interfering with their personal or family issues | 0.06 | 0.42* | 0.11 |

| 35 | The concerns that youth have regarding reproductive health are not important | 0.03 | 0.39* | 0.08 |

| 37 | If a young woman comes into a health facility and says she has been the victim of sexual assault, she probably did something to deserve it | −0.06 | 0.46* | −0.03 |

| 51 | If a client does not volunteer information to me that they have been subject to violence perpetrated by members of their family, I shouldn’t ask them directly about it because it is none of my business | 0.05 | 0.35* | 0.01 |

| 52 | By definition, boys cannot be the victims of sexual assault | −0.06 | 0.45* | −0.03 |

| Subscale 3: Attitudes towards the service delivery environment | ||||

| 24 | Teaching unmarried youth about contraceptives is acceptable | 0.24 | 0.05 | 0.41* |

| 33 | Youth should be given the same level of confidentiality when receiving sexual and reproductive health services as adults | −0.11 | 0.07 | 0.38* |

| 38 | Women and men of all ages should be welcomed into the clinic for sexual and reproductive health services if they seek them | 0.24 | 0.06 | 0.52* |

| 40 | It is important to make sure that any services provided to youth are done so privately so no one else in the clinic can hear | −0.23 | 0.21 | 0.44* |

| 41 | Educational materials on sexual and reproductive health should be openly available to unmarried boys and girls | 0.13 | −0.11 | 0.64* |

| 42 | Schools and health facilities should work together to provide reproductive health information and services to youth | 0.06 | −0.01 | 0.63* |

| 43 | If a young woman says that she has experienced sexual or gender-based violence, I will call official institutions to help her | −0.28 | 0.25 | 0.36* |

| 48 | Health workers play an important role in reducing sexual and reproductive health problems among premarital adolescents | −0.13 | 0.14 | 0.50* |

*Factor loading greater than 0.3.

Cronbach’s alpha for the entire 29-item scale and for each subscale is provided in table 4, along with the mean scores (ranging from 0 to 4 points). Cronbach’s alpha ranged from 0.70 to 0.73 for each subscale, with the full scale achieving a value of 0.72. On average, the mean overall score on the scale ws 2.73, ranging from 2.23 (Attitudes towards Information and Services Offered to Youth) to 3.06 (norms and personal beliefs).

Table 4.

Mean scores and Cronbach alpha for the full Healthcare provider attitudes scale and Subscales

| Mean | SD | Min | Max | Possible range of scores | Alpha | |

| Full Provider Attitudes Scale (30 items) | 2.73 | 0.28 | 1.79 | 3.65 | 0–4 | 0.72 |

| Subscales | ||||||

| Attitudes towards information and services offered to youth (11 items) | 2.23 | 0.42 | 1.27 | 3.55 | 0–4 | 0.70 |

| Norms and personal beliefs (10 items) | 3.06 | 0.43 | 1.3 | 4 | 0–4 | 0.70 |

| Attitudes towards the service delivery environment (eight items) | 2.91 | 0.50 | 1 | 4 | 0–4 | 0.73 |

Regression results

Finally, the results of our simple linear regression analysis suggest that respondents who had received SRH training had a mean score that was 16% higher (0.64 points; 95% CI 0.02 to 0.11; p<0.01) on the full attitudes scale compared with those who did not. With regard to the subscales, respondents who had received SRH training had a mean score that was 23% higher on the ‘Norms and Personal Beliefs’ subscale (0.93 points; 95% CI 0.18 to 0.17; p<0.05) and 25% higher on the ‘Attitudes Towards the Service Delivery Environment’ subscale (0.99 points; 95% CI 0.13 to 0.18; p<0.05). We did not find a significant association between training and a provider’s mean score on the ‘Attitudes Towards Information and Services Offered to Youth’ subscale.

Discussion

This paper describes a process to formally develop and validate a scale to measure healthcare provider attitudes in support of youth-friendly SRH service provision according to standard psychometric methods. The final 29-item scale as a whole, as well as the three identified subscales, all exhibit high internal consistency reliability which suggests that future research could use the full scale in its entirety or administer individual subscales.51 The three dimensions extracted from the original item pool correspond to clear conceptual ideas that are theoretically based within the framework of youth-friendly SRH services. Even though the items in the scale were generated to align with the five underlying domains of accessibility, acceptability, equity, appropriateness and effectiveness, many of the individual items in the initial item pool related to multiple domains and as such, we did not expect the final factor solution to fully match these five areas.

The items retained in the final scale and their organisation into the three subscales appear to reflect social and cultural issues specific to Jordan and the Middle East, which may be similar to other relatively conservative contexts. Many of the items that were retained in the ‘Attitudes toward information and services offered to youth’ and the ‘Norms and Personal Beliefs’ subscales reflect value judgements in determining which services are appropriate for youth. A study in a conservative, religious context in Africa found that counselling adolescents on SRH issues caused ethical concerns for providers as their attitudes reflected the norms of the community, which may suggest that providers were not adequately prepared to put their own beliefs aside to deal with issues related to adolescent sexuality.5 Similarly, a qualitative study in Kenya found that providers were not comfortable providing SRH services to youth and they felt torn between their traditional values and their role as service providers.52 As such, while certain items are specific to norms in the Middle East, the scale may also be easily adapted to other relatively conservative or religious settings in other parts of the world where youth sexual behaviour is closely monitored or stigmatised with some revision to ensure that scale items reflect local, common concerns specific to that setting without affecting the underlying construct being measured.

Items that relate to confidentiality emerged across the subscales in ways that highlight specific concerns in the Jordanian context. In Jordan, parents are often deeply involved in their children’s lives, with emphasis placed on a strong family unit.53 54 Social norms also emphasise the importance of privacy in relation to events that take place in the home; individuals who breach that privacy, especially in the case of sexual and gender-based violence, may be punished.55–57 Several items retained in the scale relate to confidentiality with regard to the service delivery environment, while some items specifically focus on whether parents should be informed if a child seeks SRH services. Interestingly, in the ‘Norms and Personal Beliefs’ subscale, two items retained specifically emphasise the role of the service provider in asking about the family environment.

Equity with regard to gender and marital status also emerged as an important theme within the ‘Attitudes towards Information and Services Offered to Youth’ and the ‘Norms and Personal Beliefs’ subscales and are particularly important issues within the Middle East. In terms of gender equity, men in Jordan typically do not seek SRH services as a result of strict gender norms that place such issues in the woman’s domain.24 58 As such, it is likely that health service providers have limited interaction with men in relation to SRH services. As for marital status, conservative social and religious norms in Jordan and throughout the Middle East prohibit sexual activity outside of marriage and youth who engage in premarital sexual behaviour may face dire social consequences. Ensuring providers are well equipped to handle interactions with both unmarried youth and men is critical to ensuring youth-friendly SRH service provision.

With regard to construct validity, the positive associations observed between providers who had SRH training and their mean overall score and on the ‘Norms and Personal Beliefs’ and the ‘Service Delivery Environment’ subscales provide evidence that our scale is associated with a theoretically similar variable. However, we note that there is no association observed between providers who were trained on SRH and their mean score on the ‘Attitudes about Information and Services Provided to Youth’ subscale. This may be potentially be related to the fact that many of these items focus on interpersonal interactions with youth, which is a specific skillset that is often not included in provider trainings and is also one of the more challenging areas to address. Previous research in Jordan has found that provider counselling skills on family planning tend to be weak in Jordan, and that improved provider training in this area is specficially needed;59 thus, the lack of association observed between a provider’s receipt of training and the ‘Attitudes about Information and Services Provided to Youth’ subscale may simply reflect the general need to improve provider trainings with regard to counselling and interpersonal interactions with clients in this context.

While this study contributes to an understudied area of research, the results should be interpreted in light of several limitations. As the goal of this study is to develop a scale, the intended purpose is not to describe provider attitudes using a generalisable sample of providers in Jordan. In addition, while we do not expect providers in the public sector to differ dramatically from those in the private sector, we did not include private sector providers in our study, which is an important source of health services for youth in Jordan. Our approach to generating items for inclusion in the scale was based on retrieving items from the literature and working with experts and service providers to ensure content validity. The content validity of our scale may have been improved by involving youth in our item generation process, we drew instead on the results of previous studies conducted among youth in Jordan on their concerns related to provider interactions in the context of SRH service delivery to form the basis of the items that we added to the measure to ensure these perspectives were reflected.

Future research using our scale should be conducted in clinical settings in Jordan to describe provider attitudes that incorporates providers from multiple sectors, including those working on behalf of non-governmental organisations and the private sector, in order to further validate our scale. Our scale could also be validated in other contexts, especially elsewhere in the Middle East to assess its generalisability as some of the items included in the scale may be of specific relevance to the Jordanian context. Further, while there is an emphasis on certain items that focus on SRH topics that are priorities in the Jordanian context, such as sexual and gender-based violence, many of the items may still be relevant in other culturally conservative or religious settings and the topical domains of the questions could be altered to emphasise SRH priorities among youth in a given context.

Conclusions

Given the important role that providers play in ensuring the delivery of youth-friendly SRH services, there is a need for more consistent measurement of provider attitudes to enable comparisons across study settings and to track progress over time. This study represents an initial step towards that goal, and may serve as a base for future research with larger study populations and in other settings. The provider attitudes scale towards youth-friendly services described in this paper has high validity and reliability as measured with a sample of Jordanian healthcare providers. Further, it identifies three domains: (1) ‘Attitudes Towards Information and Services Offered to Youth’, (2) ‘Norms and Personal Beliefs’ and (3) ‘Attitudes Towards the Service Delivery Environment.’

Using this scale as a means to better understand providers’ perspectives on the barriers to providing improved quality care to youth would offer an opportunity to develop important and tangible recommendations that are directly relevant to improving health services targeting youth across the region and globally.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors were involved in conceptualisation of the study design and development of study methods, instruments, and protocol. JG wrote the first draft and conducted the analysis. AO, RA-Q, AS, MA, ILH, MD and AL provided critical input and revisions. All authors approved of the final draft. JG is responsible for the overall content as the guarantor.

Funding: This work is part of the Sexual and Reproductive Health Research Programme with project number W 08.560.012, which is financed by the WOTRO Science for Global Development of the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO).

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of NWO/WOTRO.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data are available on reasonable request.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

This study obtained ethical approval at the institutional review boards (IRB) at the Harvard TH Chan School of Public Health’s IRB (Protocol# IRB19-0813) and University of Jordan IRB. Participants gave informed consent to participate in the study before taking part.

References

- 1.Chandra-Mouli V, Svanemyr J, Amin A, et al. Twenty years after International Conference on population and development: where are we with adolescent sexual and reproductive health and rights? J Adolesc Health 2015;56:S1–6. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.09.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Morris JL, Rushwan H. Adolescent sexual and reproductive health: the global challenges. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2015;131 Suppl 1:S40–2. 10.1016/j.ijgo.2015.02.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics . Aolescent sexual and reproductive health. London: FIGO, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tangmunkongvorakul A, Kane R, Wellings K. Gender double standards in young people attending sexual health services in northern Thailand. Cult Health Sex 2005;7:361–73. 10.1080/13691050500100740 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Warenius LU, Faxelid EA, Chishimba PN, et al. Nurse-Midwives' attitudes towards adolescent sexual and reproductive health needs in Kenya and Zambia. Reprod Health Matters 2006;14:119–28. 10.1016/S0968-8080(06)27242-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wood K, Jewkes R. Blood blockages and scolding nurses: barriers to adolescent contraceptive use in South Africa. Reprod Health Matters 2006;14:109–18. 10.1016/S0968-8080(06)27231-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McCleary-Sills AW, Stoebenau K, Hollingworth G. Understanding the adolescent family planning evidence base. Washington DC: ICRW, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bankole A, Malarcher S. Removing barriers to adolescents' access to contraceptive information and services. Stud Fam Plann 2010;41:117–24. 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2010.00232.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mmari KN, Magnani RJ. Does making clinic-based reproductive health services more youth-friendly increase service use by adolescents? Evidence from Lusaka, Zambia. J Adolesc Health 2003;33:259–70. 10.1016/S1054-139X(03)00062-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ross DA, Dick B, Ferguson J. Preventing HIV/AIDS in young people: a systematic review of the evidence from developing countries. WHO, 2006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Senderowitz J. Making reproductive health services youth friendly, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 12.World Health Organization . Making health services adolescent friendly: developing national quality standards for adolescent friendly health services, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tylee A, Haller DM, Graham T, et al. Youth-friendly primary-care services: how are we doing and what more needs to be done? The Lancet 2007;369:1565–73. 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60371-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brittain AW, Loyola Briceno AC, Pazol K, et al. Youth-Friendly family planning services for young people: a systematic review update. Am J Prev Med 2018;55:725–35. 10.1016/j.amepre.2018.06.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ambresin A-E, Bennett K, Patton GC, et al. Assessment of youth-friendly health care: a systematic review of indicators drawn from young people's perspectives. J Adolesc Health 2013;52:670–81. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.12.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mazur A, Brindis CD, Decker MJ. Assessing youth-friendly sexual and reproductive health services: a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res 2018;18:216. 10.1186/s12913-018-2982-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Evens E, Otieno-Masaba R, Eichleay M, et al. Post-abortion care services for youth and adult clients in Kenya: a comparison of services, client satisfaction and provider attitudes. J Biosoc Sci 2014;46:1–15. 10.1017/S0021932013000230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vernon R, Durá M. Improving the reproductive health of youth in Mexico, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mngadi PT, Faxelid E, Zwane IT, et al. Health providers' perceptions of adolescent sexual and reproductive health care in Swaziland. Int Nurs Rev 2008;55:148–55. 10.1111/j.1466-7657.2007.00625.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chilinda I, Hourahane G, Pindani M. Attitude of health care providers towards adolescent sexual and reproductive health services in developing countries: a systematic review. Health 20141706;6. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tilahun M, Mengistie B, Egata G, et al. Health workers' attitudes toward sexual and reproductive health services for unmarried adolescents in Ethiopia. Reprod Health 2012;9:19. 10.1186/1742-4755-9-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ahanonu EL. Attitudes of healthcare providers towards providing contraceptives for unmarried adolescents in Ibadan, Nigeria. J Family Reprod Health 2014;8:33. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.InJordan Communication Advocacy and Policy (JCAP) . Policies, legislation and strategies related to family planning in Jordan: review and recommendations. Amman: JCAP, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Khalaf I, Abu Moghli F, Froelicher ES. Youth-friendly reproductive health services in Jordan from the perspective of the youth: a descriptive qualitative study. Scand J Caring Sci 2010;24:321–31. 10.1111/j.1471-6712.2009.00723.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Johns Hopkins University Center for Communication Programs . Jordanian youth survey: knowledge, attitudes and practices on reproductive health and life planning 2001.

- 26.Gausman J, Othman A, Dababneh A, et al. Landscape analysis of family planning research, programmes and policies targeting young people in Jordan: stakeholder assessment and systematic review. East Mediterr Health J 2020;26:1115–34. 10.26719/emhj.20.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Haynes SN, Richard DCS, Kubany ES. Content validity in psychological assessment: a functional approach to concepts and methods. Psychol Assess 1995;7:238–47. 10.1037/1040-3590.7.3.238 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.DeVellis RF. Scale development: theory and applications. vol. 26. Sage, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Boateng GO, Neilands TB, Frongillo EA, et al. Best practices for developing and validating scales for health, social, and behavioral research: a primer. Front Public Health 2018;6:149. 10.3389/fpubh.2018.00149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Augustine LF, Vazir S, Fernandez Rao S, et al. Psychometric validation of a knowledge questionnaire on micronutrients among adolescents and its relationship to micronutrient status of 15-19-year-old adolescent boys, Hyderabad, India. Public Health Nutr 2012;15:1182–9. 10.1017/S1368980012000055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bennett S, Woods T, Liyanage WM. A simplified general method for cluster-sample surveys of health in developing countries, 1991. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reise SP, Waller NG, Comrey AL. Factor analysis and scale revision. Psychol Assess 2000;12:287–97. 10.1037/1040-3590.12.3.287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.InStataCorp . Stata statistical software: release 14. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Frane JW. Some simple procedures for handling missing data in multivariate analysis. Psychometrika 1976;41:409–15. 10.1007/BF02293565 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.de Ligny CL, Nieuwdorp GHE, Brederode WK, et al. An application of factor analysis with missing data. Technometrics 1981;23:91–5. 10.1080/00401706.1981.10486242 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Howard MC. A review of exploratory factor analysis decisions and overview of current practices: what we are doing and how can we improve? Int J Hum Comput Interact 2016;32:51–62. 10.1080/10447318.2015.1087664 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dziuban CD, Shirkey EC. When is a correlation matrix appropriate for factor analysis? Some decision rules. Psychol Bull 1974;81:358–61. 10.1037/h0036316 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hinkin TR, Tracey JB, Enz CA. Scale construction: developing reliable and valid measurement instruments. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research 1997;21:100–20. 10.1177/109634809702100108 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cattell RB. The Scree test for the number of factors. Multivariate Behav Res 1966;1:245–76. 10.1207/s15327906mbr0102_10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.HORN JL. A rationale and test for the number of factors in factor analysis. Psychometrika 1965;30:179–85. 10.1007/BF02289447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hayton JC, Allen DG, Scarpello V. Factor retention decisions in exploratory factor analysis: a tutorial on parallel analysis. Organ Res Methods 2004;7:191–205. 10.1177/1094428104263675 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Worthington RL, Whittaker TA. Scale development research: a content analysis and recommendations for best practices. The Counseling Psychologist 2006;34:806–38. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Thurstone LL. Multiple factor analysis. Psychol Rev 1931;38:406–27. 10.1037/h0069792 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kline P. An easy guide to factor analysis. Routledge, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Spector PE. Summated rating scale construction: an introduction. Sage, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cronbach LJ. Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika 1951;16:297–334. 10.1007/BF02310555 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tavakol M, Dennick R. Making sense of Cronbach's alpha. Int J Med Educ 2011;2:53–5. 10.5116/ijme.4dfb.8dfd [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Carmines EG, Zeller RA. Reliability and validity assessment. vol. 17. Sage publications, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Streiner DL. Starting at the beginning: an introduction to coefficient alpha and internal consistency. J Pers Assess 2003;80:99–103. 10.1207/S15327752JPA8001_18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Westen D, Rosenthal R. Quantifying construct validity: two simple measures. J Pers Soc Psychol 2003;84:608–18. 10.1037/0022-3514.84.3.608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Afulani PA, Diamond-Smith N, Phillips B, et al. Validation of the person-centered maternity care scale in India. Reprod Health 2018;15:147. 10.1186/s12978-018-0591-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Godia PM, Olenja JM, Lavussa JA, et al. Sexual reproductive health service provision to young people in Kenya; health service providers' experiences. BMC Health Serv Res 2013;13:476. 10.1186/1472-6963-13-476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.DeJong J, Jawad R, Mortagy I, et al. The sexual and reproductive health of young people in the Arab countries and Iran. Reprod Health Matters 2005;13:49–59. 10.1016/S0968-8080(05)25181-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gausman J, Othman A, Daas I, et al. How Jordanian and Syrian youth conceptualise their sexual and reproductive health needs: a visual exploration using concept mapping. Cult Health Sex 2021;23:176–91. 10.1080/13691058.2019.1698769 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.UNICEF . Shattered lives: challenges and priorities for Syrian children and women in Jordan. 6, 2014: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Spencer RA, Shahrouri M, Halasa L, et al. Women's help seeking for intimate partner violence in Jordan. Health Care Women Int 2014;35:380–99. 10.1080/07399332.2013.815755 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.UN Women . Gender-Based violence and child protection among Syrian refugees in Jordan, with a focus on early marriage. Amman, Jordan: UN Women, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jordan Communication Advocacy and Policy Activity . Exploring gender norms and family planning in Jordan: a qualitative study. Abt Associates, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kamhawi S, Underwood C, Murad H, et al. Client-centered counseling improves client satisfaction with family planning visits: evidence from Irbid, Jordan. Glob Health Sci Pract 2013;1:180–92. 10.9745/GHSP-D-12-00051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2021-052118supp001.pdf (100.7KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data are available on reasonable request.