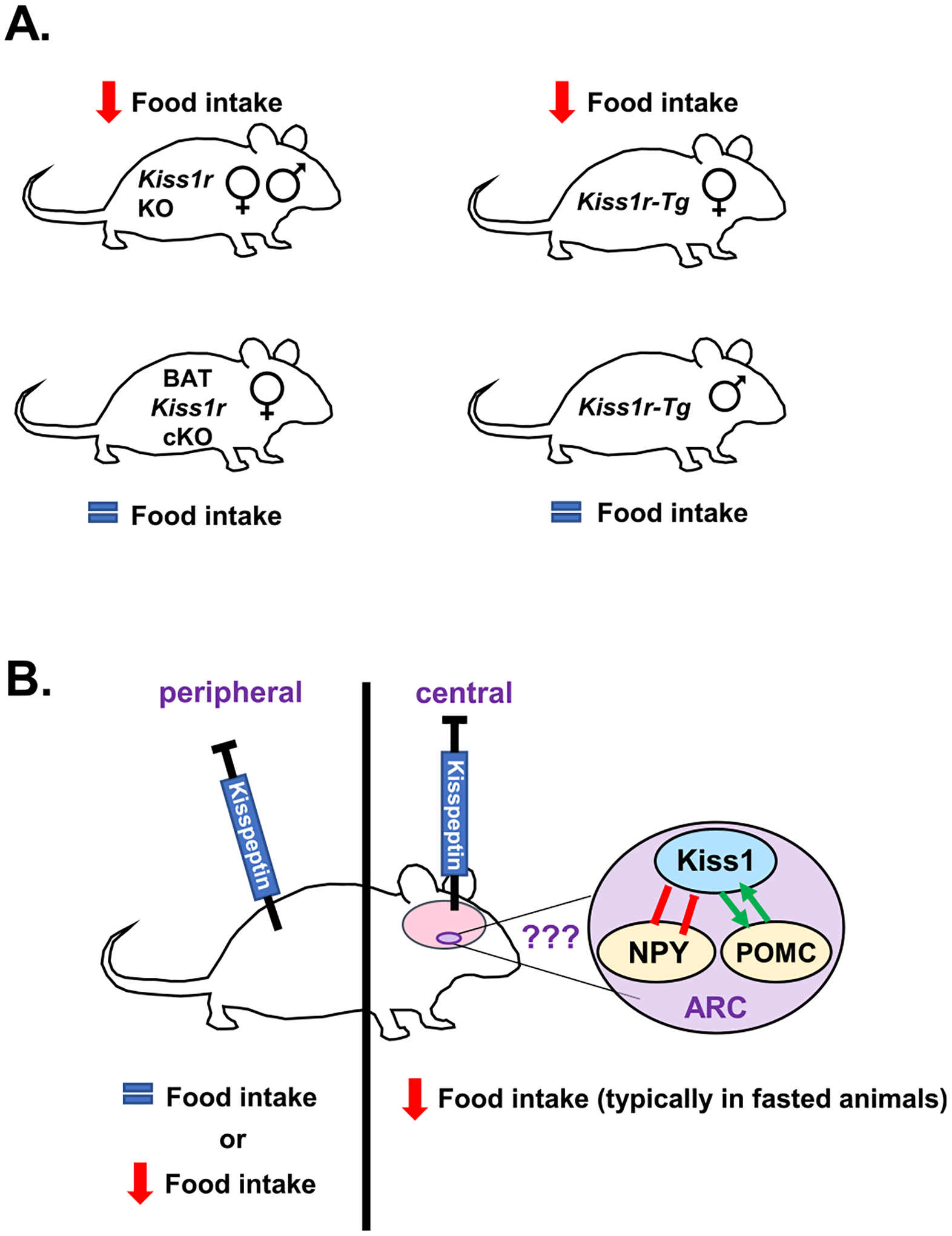

Fig. 3.

The effects of kisspeptin signaling on food intake. (A) Global Kiss1r KO male and female mice show reduced food intake, especially during the dark phase when mice consume most of their food (Tolson et al., 2014; Velasco et al., 2019). Similarly, female Kiss1r-Tg mice (global Kiss1r KOs that have KISS1R rescued back into GnRH neurons), show decreased food intake (Velasco et al., 2019), though males do not. In contrast, selective knockout of Kiss1r from just BAT (BAT Kiss1r cKO) had no effect on daily food intake (Tolson et al., 2020). (B) Rodent studies of kisspeptin administration in vivo have found either no effect on feeding or an inhibition of food intake. More specifically, several studies administering kisspeptin peripherally found no effect on food intake (Izzi-Engbeaya et al., 2018; Stengel et al., 2011) whereas one study reporting a decrease in 24 h cumulative food intake after peripheral kisspeptin treatment (Dong et al., 2020). In contrast, most studies infusing kisspeptin centrally (i.c.v) report anorexigenic effects (decreased feeding) (Sahin et al., 2015; Saito et al., 2019; Stengel et al., 2011; Talbi et al., 2016); the anorexigenic effects in rodents generally required extended fasting before the refeeding period, except for one study reporting an anorexigenic effect in ad libitum fed male rats (Cázarez-Márquez et al., 2021). The anorexigenic effects of i.c.v. kisspeptin may be due to effects on hypothalamic hunger/satiety circuits (NPY and POMC neurons which are known to be regulated by arcuate kisspeptin neurons), although other brain areas may also be involved, and this still needs more investigation.