Abstract

Suicidal ideation is elevated among individuals who engage in BDSM practices and those with sexual and gender minority (SGM) identities. There is limited research on the intersectionality of these identities and how they relate to suicidal ideation, especially within a theoretical framework of suicide risk, such as the interpersonal theory of suicide. Thus, we tested the indirect relation between BDSM disclosure and suicidal ideation through thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness, as well as the moderating role of SGM identity on these indirect associations. Participants were 125 (Mage = 28.27 years; 64% cisgender men) individuals recruited via online BDSM-related forums who endorsed BDSM involvement and recent suicidal ideation. Results indicated significant moderated mediation, such that BDSM disclosure was indirectly negatively related to suicidal ideation through lower thwarted belongingness, but not perceived burdensomeness, among SGM individuals. This was due to the significant relation between BDSM disclosure and thwarted belongingness. There were no significant moderated mediation or indirect effects related to perceived burdensomeness. We also provide supplemental analyses with positive ideation (i.e., positive thoughts toward life) as the criterion variable. In conclusion, BDSM disclosure appears to be protective against suicidal ideation through thwarted belongingness but only for SGM individuals. This work furthers our understanding of the impact of intersecting marginalized identities on suicide risk and resilience. Implications, limitations, and future directions are further discussed.

Keywords: BDSM, Sexual identity, Gender identity, Suicidal ideation, Interpersonal theory of suicide

Introduction

Individuals who identify as a sexual or gender minority (SGM; e.g., lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, or questioning) and those who endorse greater ambiguity about their sexual self-concept are at elevated risk for suicidal ideation (e.g., Gilman et al., 2001; Grossman & D’augelli, 2007; Haas et al., 2010; King et al., 2008; Talley et al., 2016; Woodward et al., 2013). Research examining suicidal ideation among individuals who engage in other less common sexual practices, such as bondage and discipline, dominance and submission, and sadomasochism (BDSM), is extremely limited (Brown et al., 2017; Cramer et al., 2017; Roush et al., 2017; Spengler, 1977). BDSM is a heterogeneous concept that Kolmes et al. (2006) detail as a “practice, a lifestyle, an identity, and an orientation” (p. 305). Considering that BDSM involves sexual practices and identities that differ from the majority of society, BDSM practitioners may experience similarly elevated rates of suicidal ideation as SGM individuals due to their sexual behavior minority status.

A recent study found that in an adult sample of BDSM practitioners recruited through the National Coalition of Sexual Freedom, a community advocacy organization, 48.6% were at an elevated risk for suicidal ideation and behaviors (Cramer et al., 2017). A separate study found that in a sample of adult BDSM practitioners recruited online via BDSM-related groups or forums, 37.4% reported recent suicidal ideation ranging in severity (Roush et al., 2017). These findings suggest BDSM practitioners may experience elevated rates of suicidal ideation similar to SGM individuals. Although these findings suggest identification as either a SGM or a BDSM practitioner may confer risk for suicidal ideation and behavior, research has yet to examine the intersectionality of multiple sexual minority statuses on suicide risk. Further, the role of experiences that are specific to sexual minorities (e.g., disclosure of sexual minority identity and practices) has not been examined within a theoretical model of suicide risk. This work is vital to the research mission of understanding the impact of intersecting marginalized identities on suicide risk and resilience (Ferlatte et al., 2018; Tucker, 2019).

The interpersonal theory of suicide (Joiner, 2005; Van Orden et al., 2010) may be a useful theoretical framework to better understand suicidal ideation among BDSM practitioners who also identify as a SGM. The interpersonal theory of suicide proposes that suicidal ideation is caused by the simultaneous presence of thwarted belongingness (TB) and perceived burdensomeness (PB), along with a sense of hope-lessness that these states are unable to change. TB refers to a perceived disconnection from others and a lack of reciprocally caring relationships, whereas PB refers to feelings of self-hatred and the belief that one’s life is a liability to others. A recent study suggests that TB and PB are associated with suicidal ideation among BDSM practitioners (Roush et al., 2017); however, it is unclear how these associations may be influenced by BDSM-specific experiences. Thus, there is a need to identify BDSM-specific experiences that may serve as risk or protective factors for suicidal ideation through TB and PB, such as the disclosure of sexual identity and practices.

The literature regarding the effects of disclosure of marginalized sexual identity and practices more broadly has been mixed. There are findings that suggest there may be negative consequences to sexual identity disclosure that could potentially elevate suicidal ideation through TB and PB. For example, considering SGM individuals and BDSM practitioners experience stigma, prejudice, and discrimination, disclosure of sexual identity and practices to others may be distressing (e.g., Bezreh et al., 2012; Grant et al., 2011; Iannotti, 2014; Kelleher, 2009; Ragins et al., 2007; Solomon et al., 2015; Wright, 2008). In fact, both SGM individuals and BDSM practitioners report negative experiences regarding the disclosure of their sexual interests and practices to others, such as alienation, harm to family relationships, and fear of disapproval (Perrin-Wallqvist & Lindblom, 2015; Wright, 2008). These experiences may decrease reciprocal caring relationships and increase feelings of loneliness, which would produce feelings of TB. Additionally, SGM individuals and BDSM practitioners report experiencing job loss following disclosure, feelings of shame, and beliefs that disclosure would be a burden on the recipient (Bezreh et al., 2012; Perrin-Wallqvist & Lindblom, 2015; Wright, 2008), which may lead to feelings of liability on others and low self-worth, which characterizes feelings of PB. These collective findings based on disclosure of marginalized sexual identities and practices, including BDSM, suggest that disclosure of sexual identity and practices by BDSM practitioners may contribute to greater experiences of TB and PB that are subsequently linked to suicidal ideation.

On the contrary, there is also substantial evidence to suggest disclosure of marginalized sexual identities and practices may serve as a protective factor against suicidal ideation. In fact, previous findings among SGM individuals suggest non-disclosure of sexual orientation may be associated with greater TB and PB, such that non-disclosure was related to poorer psychological well-being (e.g., lower self-acceptance, fewer positive relations with others; Durso & Meyer, 2013), a decreased sense of belonging with their peers or families, and feelings of alienation and difficulties with self-acceptance (Perrin-Wallqvist & Lindblom, 2015). Further, SGM individuals and BDSM practitioners report positive experiences as a result of disclosure of their sexual interests and practices. For example, SGM individuals’ disclosure of their sexual identity was associated with numerous positive outcomes, such as higher self-esteem, positive effect, and fewer depressive symptoms (Coulombe & de la Sablonnière, 2015; Kosciw et al., 2015), as well as an increased sense of belonging (Perrin-Wallqvist & Lindblom, 2015). Further, research has shown that interpersonal factors, such as autonomy support (Legate & Ryan, 2014; Legate et al., 2017; Ryan et al., 2017) and acceptance (Ryan et al., 2010), facilitate well-being following disclosure of SGM identity. Moreover, SGM individuals who have disclosed their sexual identity to more individuals (e.g., friends, family, co-workers) report more close relationships that offer social support, lower TB and PB, and lower suicidal ideation and behaviors (Morris et al., 2001; Plöderl et al., 2014). Similarly, a sense of belonging to the SGM community has been associated with greater satisfaction with current social support and better psychosocial well-being (Lin & Israel, 2012), as well as lower risk for depression in SGM adolescents (McCallum & McLaren, 2010). Disclosure of BDSM practices, specifically, also appears to be related to suicide resilience factors. The benefits of disclosing BDSM practices include finding BDSM social groups that offer a sense of belonging, connection, and acceptance (Bezreh et al., 2012; Graham et al., 2016). In fact, a previous study found that the majority of individuals who engage in BDSM (79%) are involved in BDSM social groups in order to gain a sense of community and form personal relationships (Sprott, 2010 as cited in Meeker, 2011). These findings suggest that for SGM individuals and BDSM practitioners, non-disclosure may be detrimental, whereas disclosure of sexual identity and practices may be a protective factor for suicidal ideation through decreased TB and PB.

Research has yet to examine the intersectionality of these sexual identities; however, disclosure of one sexual minority status in the context of another may mitigate potential negative effects of the secondary disclosure. It is possible that individuals with multiple marginalized identities have already experienced the negative effects of disclosure, and their remaining relationships are less likely to involve further social risk (e.g., rejection, discrimination). It is also possible that these individuals are more likely to be involved in social networks that may be more accepting and supportive of marginalized sexual identities; thus, risks of disclosure are minimized, while potential benefits (e.g., sense of belonging) are maximized. Therefore, it is plausible that disclosure of intersecting identities, such as BDSM identity and practices and SGM identity, may be protective against suicidal ideation through lowered TB and PB.

The current study tested the indirect relation between frequency of disclosure of BDSM identity and involvement (hence-forth referred to as BDSM disclosure) and suicidal ideation through TB and PB, as well as the moderating role of SGM identity, among BDSM practitioners. We hypothesized that the relation between BDSM disclosure and suicidal ideation would be associated through TB and PB, independently. Specifically, we predicted that greater BDSM disclosure would be associated with lower TB and PB, and thereby lower suicidal ideation. In this model, we predicted that the negative relation between BDSM disclosure and TB or PB would be stronger for BDSM practitioners who also identify as a SGM compared to BDSM practitioners who do not identify as a SGM. We also include supplemental analyses with positive ideation (i.e., positive thoughts toward life) as the criterion variable, expecting negative associations between TB or PB and positive ideation.

Method

Participants and Procedure

Participants were recruited as part of a larger study on BDSM and suicide risk (Brown et al., 2017; Roush et al., 2017). These analyses reflect one of the study’s primary aims and have not been previously examined. Participants were recruited via online survey methods in which a hyperlink to an anonymous survey was posted to BDSM-related groups or forums on social networking websites (i.e., Facebook, Yahoo Groups, Reddit, Literotica). Potential participants were informed that the study aimed to understand sexual activities and mental health among BDSM practitioners for the purpose of improving mental health care among BDSM practitioners. After obtaining informed consent, the demographic questionnaire was presented first, followed by self-report assessments that were presented in a random order to prevent sequencing effects. As part of the larger study, self-report assessments of sexuality and BDSM behaviors, suicide risk (e.g., acquired capability, suicidal ideation), and mental health (e.g., depression, shame, guilt) were included; however, only details for the measures used in these analyses are provided below. Participants were not compensated for their participation and could discontinue at any time. The only eligibility criterion was that participants were required to be 18 years or older. Following participation, participants were debriefed, during which the aim of the study was reiterated, and a mental health resource sheet (including suicide crisis phone numbers) was provided. All procedures were conducted in accordance with the approved protocol on file with the university’s Institutional Review Board.

A total of 576 who endorsed some level of BDSM involvement (i.e., sex involving BDSM or BDSM is an integral part of my life, not just sex) were enrolled in the larger study. Only participants who correctly responded to four out of five validity check items (e.g., “Answer this item with Agree”), which were included throughout the survey to ensure accurate and attentive responding, were retained. For the current study, only participants who completed the self-report measures used in the analyses (n = 341) and endorsed a nonzero level of suicidal ideation (i.e., one or greater on the Positive and Negative Suicide Ideation Inventory-negative ideation subscale; Osman et al., 1998) were retained, resulting in a final sample of 125 BDSM practitioners with a recent history of suicidal ideation. See Table 1 for demographic information for the full sample, SGM subsample, and non-SGM subsample.

Table 1.

Demographics, descriptive, and reliability statistics for the overall sample, the SGM subsample, and the non-SGM subsample

| Overall sample | SGM | Non-SGM | t/χ2 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample size: % (n) | 100% (125) | 44.8% (56) | 55.2% (69) | ||

| Age: mean (SD) | 28.27 (9.79) | 26.96 (8.21) | 29.30 (10.83) | 1.33 | .187 |

| Gender: % (n) | 18.00 | .001 | |||

| Cisgender men | 64.0% (80) | 44.6% (25) | 79.9% (55) | ||

| Cisgender women | 31.2% (39) | 44.6% (25) | 20.3% (14) | ||

| Other | 4.0% (5) | 9.0% (5) | – | ||

| Did not report | 0.8% (1) | 1.8% (1) | – | ||

| Ethnicity: % (n) | 3.59 | .058 | |||

| Hispanic | 6.4% (8) | 1.8% (1) | 10.1% (7) | ||

| Non-Hispanic | 92.0% (115) | 96.4% (54) | 88.4% (61) | ||

| Did not report | 1.6% (2) | 1.8% (1) | 1.4% (1) | ||

| Race: Percent (n) | 9.60 | .087 | |||

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 0.8% (1) | 1.8% (1) | – | ||

| Asian or Asian-American | 4.0% (5) | – | 7.3% (5) | ||

| Black or African-American | 0.8% (1) | 1.8% (1) | – | ||

| Hispanic or Latina/o | 2.4% (3) | – | 4.3% (3) | ||

| Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander | – | – | – | ||

| White | 82.4% (103) | 87.5% (49) | 78.3% (54) | ||

| Multiracial | 8.8% (11) | 7.1% (4) | 10.1% (7) | ||

| Did not report | 0.8% (1) | 1.8% (1) | – | ||

| Sexual orientation: % (n) | |||||

| Heterosexual or straight | 55.2% (69) | – | 100% (69) | ||

| Gay/lesbian | 0.8% (1) | 1.8% (1) | – | ||

| Bisexual | 25.6% (32) | 57.1% (32) | – | ||

| Unsure/questioning | 5.6% (7) | 12.5% (7) | – | ||

| Other | 12.8% (16) | 28.6% (16) | – | ||

| Suicide attempt history: % (n) | 24.0% (30) | 37.5% (21) | 13.0% (9) | 10.97 | .001 |

| BDSM involvement | |||||

| BDSM fantasies only | 27.2% (34) | 19.6% (11) | 33.3% (23) | ||

| Most sex does not include BDSM | 25.6% (32) | 17.9% (10) | 31.9% (22) | ||

| Sex includes BDSM half of the time | 20.8% (26) | 25% (14) | 17.4% (12) | ||

| Most sex includes BDSM | 16.0% (20) | 23.2% (13) | 10.1% (7) | ||

| All sex includes BDSM | – | – | – | ||

| BDSM is an integral part of my life | 10.4% (13) | 14.3% (8) | 7.2% (5) | ||

| BDSM disclosure: mean (SD) | 14.70 (17.68) | 20.50 (19.90) | 10.00 (14.13) | −3.45 | .001 |

| Close friends | 26.25 (35.28) | 36.71 (39.75) | 17.75 (28.79) | ||

| Family | 4.16 (13.87) | 6.86 (18.66) | 1.94 (7.49) | ||

| Strangers/acquaintances | 13.51 (22.38) | 17.93 (21.59) | 9.93 (22.51) | ||

| INQ: mean (SD); Cronbach’s alpha | |||||

| TB | 33.85 (11.13); α = .73 | 32.66 (12.41); α = .90 | 34.82 (9.96); α = .83 | 1.08 | .280 |

| PB | 14.84 (6.74); α = .76 | 15.50 (7.22); α = .76 | 14.30 (6.32); α = .75 | −0.99 | .326 |

| PANSI: mean (SD); Cronbach’s alpha | |||||

| Negative ideation | 16.65 (6.57); α = .92 | 17.16 (7.25); α = .92 | 16.23 (5.99); α = .92 | −0.79 | .433 |

| Positive ideation | 18.06 (4.79); α = .86 | 17.96 (4.65); α = .83 | 18.13 (4.93); α = .88 | 0.19 | .847 |

SGM = sexual gender minority; suicide attempt history (coded 0 = no previous suicide attempts, 1 = one or more previous suicide attempts); BDSM disclosure = the percentage of time participants disclosed their BDSM identity or activities with others calculated by averaging three disclosure items based on social category (i.e., close friends, family, strangers/acquaintances); INQ = Interpersonal Needs Questionnaire; TB = Thwarted belongingness subscale from the INQ. PB = Perceived burdensomeness subscale, INQ; PANSI = Positive and Negative Suicide Ideation Inventory; Negative ideation = Negative ideation subscale (suicidal ideation), PANSI; Positive ideation = Positive ideation subscale, PANSI. Participants were provided the option to identify as more than one race

Measures

Demographic and Sexuality Questionnaire

Participants were asked to provide demographic information (e.g., age, gender, ethnicity), as well as information pertaining to suicide risk (e.g., suicide attempt history [coded 0 = no previous suicide attempts, 1 = one or more previous suicide attempts]; “Have you attempted suicide? If so, how many times?”). Additionally, participants provided information related to gender identity, sexuality, and BDSM involvement, which were used as variables in our primary analyses (detailed below).

BDSM Involvement

Participants were asked to indicate their current level of BDSM involvement on the following scale: 0 = No BDSM involvement, 1 = BDSM fantasies only, 2 = Most sex does not include BDSM, 3 = Sex includes BDSM about half the time, 4 = Most sex includes BDSM, 5 = All sex includes BDSM, and 6 = BDSM is an integral part of my life, not just sex. Only participants who reported some level of BDSM involvement (> 0) were retained in the analyses. Descriptive statistics for BDSM involvement are presented in Table 1.

SGM Identity

Participants reported how they presently identify their sexual orientation (heterosexual/straight, gay/lesbian, bisexual, unsure/questioning, other) and gender (cisgender male, cisgender female, transgender [male to female], transgender [female to male], other). Their responses were coded into a dichotomous variable as SGM (coded 1) or non-SGM (coded 0) based on their reported sexual orientation and gender identity. For the purposes of this study, participant responses in which the individual identified as either cisgender male or cisgender female and identified as heterosexual/straight were coded as non-SGM; otherwise, participant responses were coded as SGM. Given the low number of participants in each unique SGM identity group (as seen in Table 1), we were not able to analyze each unique SGM group separately.

BDSM Disclosure

Participants were asked to independently rate on a scale of 0–100, “What percentage of time do you disclose your identity in the BDSM community or your BDSM activities with…” individuals in three different social categories (i.e., close friends, family, and strangers/acquaintances). To determine the average percentage of BDSM disclosure, the percentage of time participants disclosed was averaged across the three social categories (i.e., close friends, family, strangers/acquaintances). The averaged BDSM disclosure score was used to represent BDSM disclosure in the analyses. Bivariate and descriptive statistics for BDSM disclosure are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Bivariate correlations for the overall sample

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. TB | – | |||||

| 2. PB | .42** | – | ||||

| 3. BDSM disclosure | − .24** | .04 | – | |||

| 4. SGM identity† | − .10 | .09 | .30** | – | ||

| 5. Suicidal ideation | .52** | .51** | .03 | .07 | – | |

| 6. Positive ideation | − .64** | − .42** | .04 | − .02 | − .50 | – |

TB = Thwarted belongingness subscale, Interpersonal Needs Questionnaire (INQ). PB = Perceived burdensomeness, INQ; SGM identity = sexual gender minority identity (SGM coded 1, non-SGM coded 0);

point-biserial correlation between SGM identity (dichotomous) and the other continuous variables; Suicidal Ideation = Negative ideation subscale, Positive and Negative Suicide Ideation Inventory; Positive Ideation = Positive ideation subscale, Positive and Negative Suicide Ideation Inventory* p < .05; **p < .01

Interpersonal Needs Questionnaire (INQ)

The INQ (Van Orden et al., 2012) is a 15-item self-report measure that assesses recent feelings of TB and PB. Participants respond on a 7-point ordinal response scale ranging from 1 (Not at all true for me) to 7 (Very true for me). The TB subscale consists of nine items (e.g., “These days, I feel like I belong”; “These days, I am close to other people”) that are reverse-scored as needed and sum totaled with higher scores indicating greater TB. The PB subscale includes six items (e.g., “These days, the people in my life would be better off if I were gone”; “These days, I am a burden on society”) that are sum totaled with higher scores indicating greater PB. Both the TB subscale and the PB subscale have evidenced good internal consistency, α = 0.85 and α = 0.89, respectively, and there is evidence for convergent and discriminant validity (Van Orden et al., 2012). See Table 1 for descriptive and reliability statistics and Table 2 for bivariate statistics.

Positive and Negative Suicide Ideation Inventory (PANSI)

The PANSI (Osman et al., 1998) is a 14-item self-report measure comprised of two scales: negative ideation (i.e., suicidal ideation) and positive ideation (i.e., positive thoughts toward life). Participants respond on a 5-point ordinal response scale ranging from 0 (None of the time) to 4 (Most of the time). Items on the negative ideation subscale (8 items; e.g., “Felt so lonely or sad you wanted to kill yourself so that you could end your pain?”; “Felt hopeless about the future and wondered if you should kill yourself?”) and positive ideation subscale (6 items; e.g., “Felt that life was worth living?”; “Felt confident about your plans for the future?”) are sum totaled with higher scores indicating greater positive or negative ideation during the past two weeks. Both the positive ideation subscale and the negative ideation subscale have evidenced good to excellent internal consistency across a variety of samples, α = 0.80–0.85 and α = 0.91–0.94, respectively, and there is evidence for convergent and discriminant validity (Muehlenkamp et al., 2005; Osman et al., 1998, 2003). Only participants who indicated recent suicidal ideation (negative ideation subscale score > 0) were retained for analyses. Of note, out of the original recruited sample who completed the PANSI (n = 341), 36.7% (n = 125) reported a nonzero level of suicidal ideation during the past two weeks, which is significantly higher than the 12-month prevalence of the adult population in the USA (4.3%; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2019). The negative ideation subscale score was used as the criterion in the primary analyses, and the positive suicide ideation subscale score was used as the criterion variable in the supplemental analyses. See Table 1 for descriptive and reliability statistics and Table 2 for bivariate statistics.

Data Analytic Strategy

Data analyses and preparation were conducted using SPSS-26. Missing data were minimal (1.75%), and Little’s Missing Completely at Random (MCAR) indicated that the missing data was MCAR (χ2[1119, N = 341] = 1067.73, p = 0.861); thus, expectation maximization (EM) was used to impute missing data (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2013). Prior to analyses, univariate outliers were examined for each group (SGM vs. non-SGM). Univariate outliers were minimal and ranged from 0 to 5 across the variables on interest. These were adjusted to a score within ± 3.29 standard deviations from the mean for each variable (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2013. There were no multivariate outliers.

A moderated mediation approach (Model 7; Hayes, 2013) was used to test whether the indirect association between BDSM disclosure and suicidal ideation through TB (first model) or PB (second model) would be moderated by SGM identity (i.e., SGM or non-SGM). Specifically, we hypothesized that path a would be moderated by SGM identity, such that those who identified as non-SGM would evidence a weaker association between BDSM disclosure and TB or PB, which in turn would result in a weaker indirect effect between BDSM disclosure and suicidal ideation. We utilized 10,000 bootstrap samples to construct bias-corrected 95% confidence intervals. Confidence intervals not containing zero indicate statistically significant indirect effects (Hayes, 2013). Predictor variables were mean-centered prior to analyses. In contrast to other mediation procedures (e.g., Baron & Kenny, 1986), this statistical analysis procedure does not require a significant direct path from the predictor variable to the criterion variable prior to testing indirect effects (Hayes, 2013). The conditional indirect effects, which is the effect of the mediator between the predictor variable and criterion variable that is conditional on the moderator, were determined (Hayes, 2013; Preacher & Hayes, 2008). Additionally, the index of moderated mediation and bootstrap confidence interval are provided as a formal test of moderated mediation (Hayes, 2015). Interactions were reported, and simple slopes were calculated for significant interactions to demonstrate the change in the association between BDSM disclosure and TB or PB for SGM and non-SGM individuals. Similar supplemental analyses were conducted with positive ideation as the criterion variable.

Results

Primary Analyses

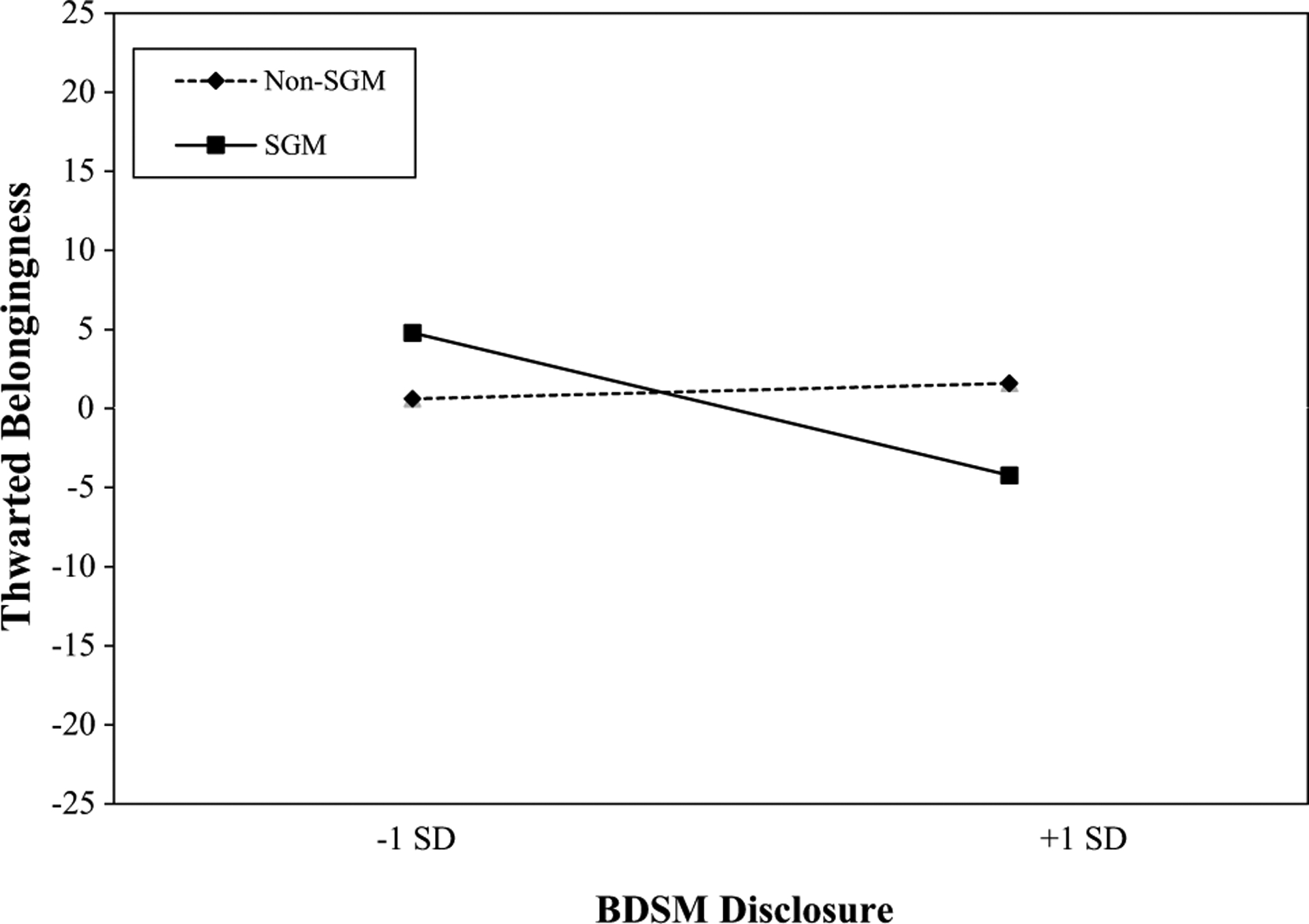

We tested the hypothesis that the indirect association between BDSM disclosure and suicidal ideation through TB would be moderated by SGM identity (Fig. 1). The full model was significant and explained 29% of the variance in suicidal ideation (F[2, 122] = 25.32, R2 = 0.29, p < 0.001). Consistent with our hypothesis, there was significant moderated mediation (index of moderated mediation = −0.09, 95% CI = −0.18, −0.02). Specifically, there was a significant indirect effect of BDSM disclosure to suicidal ideation through TB for those who identified as a SGM (indirect effect = −0.08, 95% CI = −0.15, −0.03), but not for those who did not identify as a SGM (indirect effect = 0.01, 95% CI = −0.05, 0.06). There was a significant interaction between BDSM disclosure and SGM identity predicting TB (b = −0.28, 95% CI = −0.51, −0.05). Simple slopes analyses (Fig. 2) indicated that there was a significant negative association between BDSM disclosure and TB for those who identified as a SGM (b = −0.25, 95% CI = −0.40, −0.11); however, there was not a significant relation between BDSM disclosure and TB for those who did not identify as a SGM (b = 0.03, 95% CI = −0.15, 0.21). There was also a significant direct effect between BDSM disclosure and suicidal ideation (b = 0.06, 95% CI = 0.002, 0.12).

Fig. 1.

Moderating effect of sexual gender minority identity (SGM) on the indirect effect of thwarted belongingness in the relation between BDSM disclosure and suicidal ideation. Unstandardized path coefficients b are reported. SGM identity (coded non-SGM = 0, SGM = 1).*p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001

Fig. 2.

Simple slopes of the relation between BDSM disclosure and thwarted belongingness based on sexual gender minority identity (SGM). Individuals who identify as a SGM have a significant negative relation between BDSM disclosure and thwarted belongingness (TB; b = − 0.25, p < .001), but individuals who identify as non-SGM do not (b = 0.03, p = .761). The scale of the y-axis has been mean-centered

Next, we tested the hypothesis that the indirect association between BDSM disclosure and suicidal ideation through PB would be moderated by SGM identity (Fig. 3). The full model was significant and explained 26% of the variance in suicidal ideation (F[2, 122] = 21.42, R2 = 0.26, p < 0.001). Contrary to our hypothesis, there was not significant moderated mediation (index of moderated mediation = −0.01, 95% CI = −0.10, 0.06). Specifically, there was not a significant indirect effect of BDSM disclosure to suicidal ideation through PB for those who identified as a SGM (indirect effect = −0.003, 95% CI = −0.05, 0.05) or those who did not identify as a SGM (indirect effect = 0.01, 95% CI = −0.05, 0.08). There was also not a significant interaction between BDSM disclosure and SGM identity predicting PB (b = −0.03, 95% CI = −0.17, 0.12). There was also not a significant direct effect between BDSM disclosure and suicidal ideation (b = 0.003, 95% CI = −0.05, 0.06).1

Fig. 3.

Moderating effect of sexual gender minority identity (SGM) on the indirect effect of perceived burdensomeness in the relation between BDSM disclosure and suicidal ideation. Unstandardized path coefficients b are reported. SGM identity (coded non-SGM = 0, SGM = 1).*p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001

Supplemental Analyses

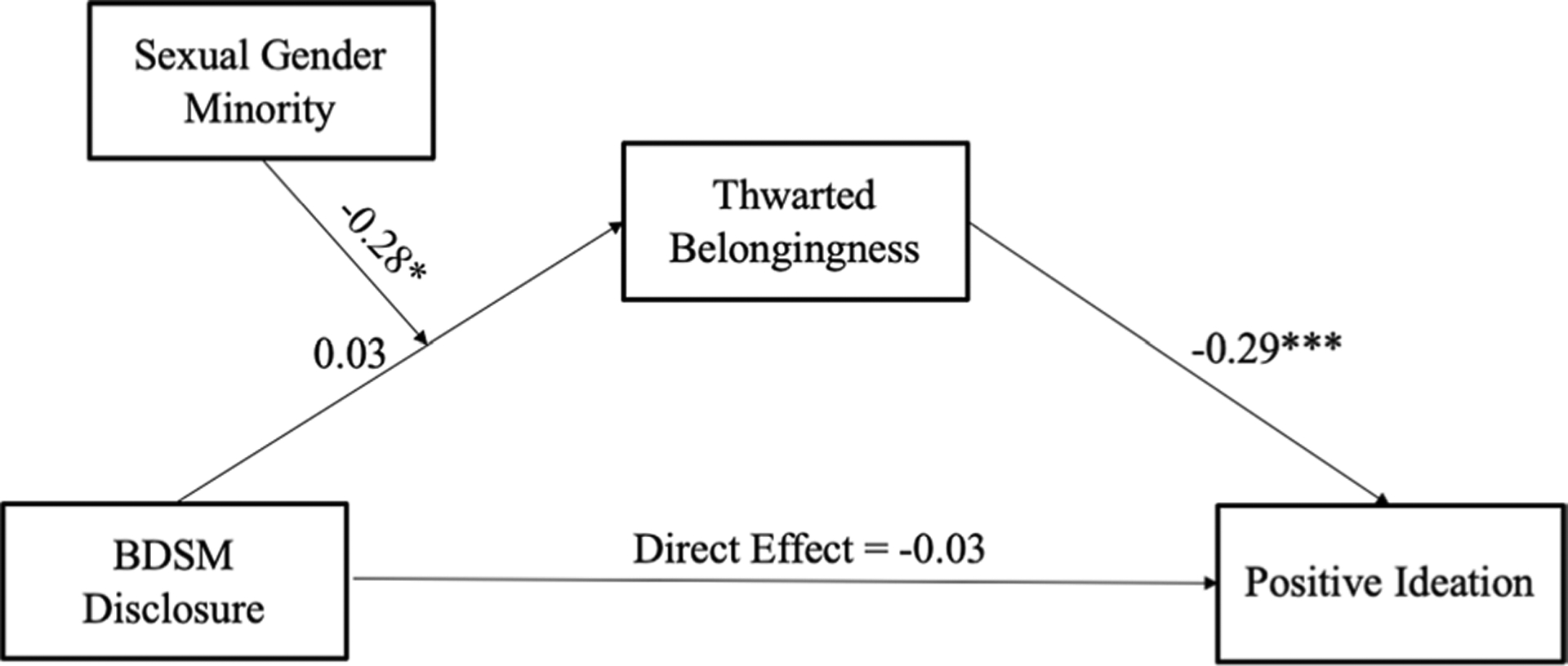

Analyses were also conducted with positive ideation as the criterion variable, given a growing body of research that suggests positive thoughts toward life and reasons for living are associated with decreased risk for suicidal ideation and behaviors (e.g., Bakhiyi et al., 2017; Brown et al., 2005; Bryan et al., 2016; Goods et al., 2020). We tested the hypothesis that the indirect association between BDSM disclosure and positive ideation through TB would be moderated by SGM identity (Fig. 4). The full model was significant and explained 42% of the variance in positive ideation (F[2, 122] = 44.13, R2 = 0.42, p < 0.001). Consistent with our hypothesis, there was significant moderated mediation (index of moderated mediation = 0.08, 95% CI = 0.01, 0.15). Specifically, there was a significant indirect effect of BDSM disclosure to positive ideation through TB for those who identified as a SGM (indirect effect = 0.07, 95% CI = 0.03, 0.13), but not for those who did not identify as a SGM (indirect effect = −0.01, 95% CI = −0.05, 0.04). There was a significant interaction between BDSM disclosure and SGM identity predicting TB (b = −0.28, 95% CI = −0.51, −0.05). Simple slopes analyses were identical to the hypothesized model since the interaction was on the a-path. There was not a significant direct effect between BDSM disclosure and positive ideation (b = −0.03, 95% CI = −0.07, 0.004).

Fig. 4.

Moderating effect of sexual gender minority identity (SGM) on the indirect effect of thwarted belongingness in the relation between BDSM disclosure and positive ideation. Unstandardized path coefficients b are reported. SGM identity (coded non-SGM = 0, SGM = 1).*p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001

We also tested the hypothesis that the indirect association between BDSM disclosure and positive ideation through PB would be moderated by SGM identity (Fig. 5). The full model was significant and explained 18% of the variance in positive ideation (F[2, 122] = 13.26, R2 = 0.18, p < 0.001. Contrary to our hypothesis, there was not significant moderated mediation (index of moderated mediation = 0.01, 95% CI = −0.04, 0.06). Specifically, there was not a significant indirect effect of BDSM disclosure to positive ideation through PB for those who identified as a SGM (indirect effect = 0.002, 95% CI = −0.03, 0.03) or those who did not identify as a SGM (indirect effect = −0.01, 95% CI = −0.05, 0.03). There was not a significant interaction between BDSM disclosure and SGM identity predicting PB (b = −0.03, 95% CI = −0.17, 0.12). There was also not a significant direct between BDSM disclosure and positive ideation (b = 0.01, 95% CI = −0.03, 0.06).

Fig. 5.

Moderating effect of sexual gender minority identity (SGM) on the indirect effect of perceived burdensomeness in the relation between BDSM disclosure and positive ideation. Unstandardized path coefficients b are reported. SGM identity (coded non-SGM = 0, SGM = 1).*p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001

Discussion

The previous literature suggests BDSM practitioners may be at an elevated risk for suicidal thoughts and behaviors (Brown et al., 2017; Cramer et al., 2017; Roush et al., 2017). The previous literature has indicated disclosure of BDSM practices and other SGM identities can have both positive (e.g., Coulombe & de la Sablonnière, 2015; Kosciw et al., 2015; Legate et al., 2017; Perrin-Wallqvist & Lindblom, 2015; Plöderl et al., 2014) and negative (e.g., Bezreh et al., 2012; Grant et al., 2011; Iannotti, 2014; Kelleher, 2009; Ragins et al., 2007; Wright, 2008) consequences. Thus, determining factors that may affect the development of suicidal ideation among BDSM practitioners is necessary to clarify the existing literature, inform future research, and guide clinical practice. No study to our knowledge has examined the relations between BDSM disclosure, SGM identity, and suicidal ideation through two key interpersonal risk factors posited by the interpersonal theory of suicide: TB and PB. To address this gap in the literature, the current study tested the role of TB and PB in the relation between BDSM disclosure and suicidal ideation and positive ideation (i.e., positive thoughts toward life), and whether SGM identity impacted the strength of these relations. This work is vital to the research mission of understanding the impact of intersecting marginalized identities (i.e., BDSM practitioners and SGM identities) on suicide risk and resilience (Ferlatte et al., 2018; Tucker, 2019).

The results of the current study suggest BDSM disclosure was associated with lower TB, which in turn was positively associated with suicidal ideation and negatively associated with positive ideation; however, this varied as a function of SGM identity, such that there was only a significant negative relation between BDSM disclosure and TB among those who also identified as a SGM individual. This finding provides preliminary evidence that BDSM disclosure may be protective against suicidal ideation and associated with greater positive ideation through reduced feelings of TB among those who also identify as a SGM. It appears that BDSM disclosure has the potential to increase feelings of social support, connection, acceptance, and belonging, in turn decreasing the severity of suicidal ideation and increased positive ideation. One possible explanation for this finding is that SGM individuals may have previously disclosed their SGM status to others, and disclosure of an additional sexual identity involved minimal interpersonal risk to existing relationships (i.e., close friends and family) but the opportunity to increase feelings of belonging. Additionally, it is also possible that many SGM individuals in the current study are more likely to be in social networks that may be more accepting and supportive of marginalized sexual identities; thus, BDSM disclosure would provide more opportunities to develop reciprocally caring relationships. Consistent with these explanations, SGM individuals (M = 20.50) were significantly more likely, on average, to engage in BDSM disclosure compared to non-SGM individuals (M = 10.00; t (123) = −3.45, p = 0.001). More research, especially longitudinal studies assessing the relative time course of identity disclosures and changes in the quality of social support across different types of relationships, is needed to understand why disclosure may be protective against suicide risk through TB among those with multiple marginalized identities.

Results of the current study also suggest that BDSM disclosure was not associated with suicidal ideation or positive ideation through PB. Additionally, at the bivariate level, PB was not associated with BDSM disclosure, but PB was positively associated with suicidal ideation and desire to live among BDSM practitioners. One possible explanation for these findings is that PB, as assessed by the INQ, may reflect more global beliefs about burden (e.g., burden on society) or intrapersonal characteristics (e.g., feeling of shame, internalized stigma, low self-esteem, self-hate) that are associated with elevated suicidal ideation and decreased positive ideation (i.e., positive thoughts toward life) even among BDSM practitioners; however, PB may be more stable and less influenced by social interactions, such as disclosure, compared to TB.

Taken together, the current findings provide support that BDSM disclosure may be protective against suicidal ideation among SGM individuals through TB, but not PB. When working with patients surrounding the topic of marginalized identity disclosure and the “coming out” process, clinicians should consider the intersectionality of multiple identity statuses and the potential for developing belonging or mitigating TB through psychosocial interventions. Although BDSM disclosure was not associated with PB in the current study, the direct association between PB and suicidal ideation suggests clinicians should assess and target PB to reduce risk for suicidal ideation. The current findings fail to provide an explanation as to why and for whom BDSM disclosure may increase risk for suicidal ideation. The previous research has demonstrated that whether or not disclosure is associated with positive and negative outcomes is dependent on the context (e.g., Legate et al., 2017); therefore, the inclusion of mediators and moderators such as expectations of rejection, discrimination, self-esteem, and autonomy in future research will better aid researchers and clinicians in understanding the context in which BDSM disclosure is detrimental and confers risk for suicide.

The results of the current study should be interpreted in light of methodological limitations. This study was cross-sectional, meaning longitudinal research is needed to determine temporal associations between these factors. This may be especially important considering research suggests SGM identity is fluid (Katz-Wise, 2015). Given the small number of participants with distinct SGM identities in this sample, we aggregated all SGM identities into one group, which does not allow for the examination of heterogeneous experiences. The item used to measure BDSM disclosure was worded to capture BDSM broadly and reflect terminology related to both identity and involvement; however, this does not allow for distinctions to be made between disclosing one’s identity and disclosing one’s involvement. Perhaps the degree of self-identification as a BDSM practitioner, beyond BDSM involvement, may impact disclosure and interpersonal risk factors; this warrants further investigation. We were also unable to examine whether the social context or types of relationships in which individuals choose to disclose their BDSM identity influences these associations due to low disclosure rates in some groups. Understanding whether BDSM disclosure is beneficial or detrimental depending on the type or quality of social relationships may directly inform clinical intervention.

The sample used in the current study was recruited via an online survey posted on BDSM-specific social media websites; thus, it is possible that the current findings may reflect important characteristics of individuals who are already engaged in some sort of BDSM community (e.g., lower internalized stigma and shame) and may not generalize to BDSM practitioners broadly. Additionally, this study examined these associations among BDSM practitioners who had recent suicidal ideation; therefore, these findings may not generalize to individuals without suicidal ideation and may not inform our understanding of factors associated with the initial onset of suicidal ideation or suicidal behaviors. Lastly, the majority of the sample identified as non-Hispanic White, which may reflect the demographic distribution of the BDSM population, but does not allow for the consideration of the intersectionality of sexual and racial identities in the development of suicide risk. Future research should consider using various recruitment methods that aim to recruit larger, more diverse samples to better understand suicidal ideation and behaviors among individuals with different SGM identities, as well as additional multiple marginalized identities.

Conclusion

The results of the current study indicate that TB, but not PB, partially explains the relation between BDSM disclosure and suicidal ideation and positive ideation (i.e., positive thoughts toward life). This study provided preliminary support for the protective role of BDSM disclosure against suicidal ideation through TB for individuals who also identified as a SGM. Future research is needed to further explore this finding and should consider additional moderating or contextual factors (e.g., previous disclosure, changes in self-esteem and connection following disclosure, other minority statuses). Although BDSM disclosure appears to be protective in this specific context, the previous literature suggests disclosure may have detrimental effects; thus, more research is needed to determine factors and contexts in which BDSM disclosure may confer risk for suicidal ideation and behaviors. The current study has continued to broaden the scant literature on BDSM practitioners’ risk for suicidal ideation; however, further work is necessary to advance our understanding of the complex experiences and processes involved in risk and resiliency for both suicidal ideation and suicidal behaviors.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the National Institute of Mental Health (T32 MH020061; R01 MH115922; L30 MH120575).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest The authors declared that there is no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval All study procedures were conducted in accordance with the Institutional Review Board-approved protocol.

Analyses were also conducted covarying for depressive symptoms (Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression Scale total score; Radloff, 1977). Given that including depressive symptoms as a covariate did not change the trends or patterns of statistical significance of the results and considering issues related to the theoretical and clinical interpretability of results that adjust for depressive symptoms (Mitchell et al., 2017; Rogers et al., 2018), the following models are presented without adjusting for depressive symptoms.

References

- Bakhiyi CL, Jaussent I, Beziat S, Cohen R, Genty C, Kahn JP, Leboyer M, Le Vaou P, Guillaume S, & Courtet P (2017). Positive and negative life events and reasons for living modulate suicidal ideation in a sample of patients with history of suicide attempts. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 88, 64–71. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2016.12.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, & Kenny DA (1986). The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51, 1173–1182. 10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bezreh T, Weinberg TS, & Edgar T (2012). BDSM disclosure and stigma management: Identifying opportunities for sex education. American Journal of Sexuality Education, 7, 37–61. 10.1080/15546128.2012.650984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown GK, Steer RA, Henriques GR, & Beck AT (2005). The internal struggle between the wish to die and the wish to live: A risk factor for suicide. American Journal of Psychiatry, 162(10), 1977–1979. 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.10.1977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown SL, Roush JF, Mitchell SM, & Cukrowicz KC (2017). Suicide risk among BDSM practitioners: The role of acquired capability for suicide. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 73, 1642–1654. 10.1002/jclp.22461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryan CJ, Rudd MD, Peterson AL, Young-McCaughan S, & Wertenberger EG (2016). The ebb and flow of the wish to live and the wish to die among suicidal military personnel. Journal of Affective Disorders, 202, 58–66. 10.1016/j.jad.2016.05.049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coulombe S, & de la Sablonnière R (2015). The role of identity integration in hedonic adaptation to a beneficial life change: The example of “coming out” for lesbians and gay men. Journal of Social Psychology, 155, 294–313. 10.1080/00224545.2015.1007028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cramer RJ, Mandracchia J, Gemberling TM, Holley SR, Wright S, Moody K, & Nobles MR (2017). Can need for affect and sexuality differentiate suicide risk in three community samples? Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 36, 704–722. 10.1521/jscp.2017.36.8.704 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Durso LE, & Meyer IH (2013). Patterns and predictors of disclosure of sexual orientation to healthcare providers among lesbians, gay men, and bisexuals. Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 10, 35–42. 10.1007/s13178-012-0105-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferlatte O, Salway T, Hankivsky O, Trussler T, Oliffe JL, & Marchand R (2018). Recent suicide attempts across multiple social identities among gay and bisexual men: An intersectionality analysis. Journal of Homosexuality, 65, 1507–1526. 10.1080/00918369.2017.1377489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilman SE, Cochran SD, Mays VM, Hughes M, Ostrow D, & Kessler R (2001). Risk of psychiatric disorders among individuals reporting same-sex sexual partners in the National Comorbidity Survey. American Journal of Public Health, 91, 933–939. 10.2105/ajph.91.6.933 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goods NAR, Page AC, Stritzke WGK, Kyron MJ, & Hooke GR (2020). Daily monitoring of the wish to live and the wish to die with suicidal inpatients. In Page AC & Stritzke WGK (Eds.), Alternatives to suicide: Beyond risk and toward a life worth living (pp. 89–110). Elsevier. 10.1016/b978-0-12-814297-4.00005-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Graham BC, Butler SE, McGraw R, Cannes SM, & Smith J (2016). Member perspectives on the role of BDSM communities. Journal of Sex Research, 53, 895–909. 10.1080/00224499.2015.1067758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant JM, Motter LA, Tanis J, Harrison J, Herman JL, & Keisling M (2011). Injustice at every turn: A report of the National Transgender Discrimination Survey. Washington, DC: National Center for Transgender Equality and National Gay and Lesbian Task Force. [Google Scholar]

- Grossman AH, & D’augelli AR (2007). Transgender youth and life-threatening behaviors. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 37, 527–537. 10.1521/suli.2007.37.5.527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas AP, Eliason M, Mays VM, Mathy RM, Cochran SD, D’Augelli AR, Silverman MM, Fisher PW, Hughes T, Rosario M, & Russell ST (2010). Suicide and suicide risk in lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender populations: Review and recommendations. Journal of Homosexuality, 58, 10–51. 10.1080/00918369.2011.534038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. Guilford Press. 10.1111/jedm.12050 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF (2015). An index and test of linear moderated mediation. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 50, 1–22. 10.1080/00273171.2014.962683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iannotti L (2014). I didn’t consent to that: Secondary analysis of discrimination against BDSM identified individuals. CUNY Academic Works. https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/229 [Google Scholar]

- Joiner T (2005). Why people die by suicide. Harvard University Press. 10.2307/j.ctvjghv2f [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Katz-Wise SL (2015). Sexual fluidity in young adult women and men: Associations with sexual orientation and sexual identity development. Psychology & Sexuality, 6, 189–208. 10.1080/19419899.2013.876445 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kelleher C (2009). Minority stress and health: Implications for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and questioning (LGBTQ) young people. Counseling Psychology Quarterly, 22, 373–379. 10.1080/09515070903334995 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- King M, Semlyen J, Tai SS, Killaspy H, Osborn D, Popelyuk D, & Nazareth I (2008). A systematic review of mental disorder, suicide, and deliberate self-harm in lesbian, gay, and bisexual people. BMC Psychiatry, 8, 70. 10.1186/1471-244x-8-70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolmes K, Stock W, & Moser C (2006). Investigating bias in psychotherapy with BDSM clients. Journal of Homosexuality, 50, 301–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosciw JG, Palmer NA, & Kull RM (2015). Reflecting resiliency: Openness about sexual orientation and/or gender identity and its relationship to well-being and educational outcomes for LGBT students. American Journal of Community Psychology, 55, 167–178. 10.1007/s10464-014-9642-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Legate N, & Ryan WS (2014). Autonomy support as acceptance for disclosing and developing a healthy lesbian, gay, bisexual or transgendered identity. In Weinstein N (Ed.), Human motivation and interpersonal relationships (pp. 191–212). Springer. 10.1007/978-94-017-8542-6_9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Legate N, Ryan RM, & Rogge RD (2017). Daily autonomy support and sexual identity disclosure predicts daily mental and physical health outcomes. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 43, 860–873. 10.1177/0146167217700399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin YJ, & Israel T (2012). Development and validation of a psychological sense of LGBT community scale. Journal of Community Psychology, 40, 573–587. 10.1002/jcop.21483 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McCallum C, & McLaren S (2010). Sense of belonging and depressive symptoms among GLB adolescents. Journal of Homosexuality, 58, 83–96. 10.1080/00918369.2011.533629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meeker C (2011). Bondage and discipline, dominance and submission, and sadism and masochism (BDSM) identity development. In Plakhotnik MS, Nielsen SM, & Pane DM (Eds.), Proceedings of the Tenth Annual College of Education & GSN Research Conference (pp. 154–161). Miami: Florida International University. http://coeweb.fiu.edu/research_conference/ [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell SM, Brown SL, Roush JF, Bolaños AD, Littlefield AK, Marshall AJ, Jahn DR, Morgan RD, & Cukrowicz KC (2017). The clinical application of suicide risk assessment: A theory-driven approach. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 24, 1406–1420. 10.1002/cpp.2086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris JF, Waldo CR, & Rothblum ED (2001). A model of predictors and outcomes of outness among lesbian and bisexual women. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 71, 61–71. 10.1037/0002-9432.71.1.61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muehlenkamp JJ, Gutierrez PM, Osman A, & Barrios FX (2005). Validation of the Positive and Negative Suicide Ideation (PANSI) Inventory in a diverse sample of young adults. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 61, 431–445. 10.1002/jclp.20051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osman A, Gutierrez PM, Jiandani J, Kopper BA, Barrios FX, Linden SC, & Truelove RS (2003). A preliminary validation of the Positive and Negative Suicide Ideation (PANSI) Inventory with normal adolescent samples. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 59, 493–512. 10.1002/jclp.10154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osman A, Gutierrez PM, Kopper BA, Barrios FX, & Chiros CE (1998). The Positive and Negative Suicide Ideation Inventory: Development and validation. Psychological Reports, 82, 783–793. 10.2466/pr0.1998.82.3.783 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrin-Wallqvist R, & Lindblom J (2015). Coming out as gay: A phenomenological study about adolescents disclosing their homosexuality to their parents. Social Behavior and Personality, 43, 467–480. 10.2224/sbp.2015.43.3.467 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Plöderl M, Sellmeier M, Fartacek C, Pichler EM, Fartacek R, & Kralovec K (2014). Explaining the suicide risk of sexual minority individuals by contrasting the minority stress model with suicide models. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 43, 1559–1570. 10.1007/s10508-014-0268-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, & Hayes AF (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods, 40, 879–891. 10.3758/brm.40.3.879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS (1977). The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1, 385–401. 10.1177/014662167700100306 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ragins BR, Singh R, & Cornwell JM (2007). Making the invisible visible: Fear and disclosure of sexual orientation at work. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92, 1103–1118. 10.1037/0021-9010.92.4.1103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers ML, Stanley IH, Hom MA, Chiurliza B, Podlogar MC, & Joiner TE (2018). Conceptual and empirical scrutiny of covarying depression out of suicidal ideation. Assessment, 25, 159–172. 10.1177/1073191116645907 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roush JF, Brown SL, Mitchell SM, & Cukrowicz KC (2017). Shame, guilt, and suicide ideation among bondage and discipline, dominance and submission, and sadomasochism practitioners: Examining the role of the interpersonal theory of suicide. Suicide and Life Threatening Behavior, 47, 129–141. 10.1111/sltb.12267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan C, Russell ST, Huebner D, Diaz R, & Sanchez J (2010). Family acceptance in adolescence and the health of LGBT young adults. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing, 23, 205–213. 10.1111/j.1744-6171.2010.00246.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan WS, Legate N, Weinstein N, & Rahman Q (2017). Autonomy support fosters lesbian, gay, and bisexual identity disclosure and wellness, especially for those with internalized homophobia. Journal of Social Issues, 73(2), 289–306. 10.1111/josi.12217 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Solomon D, McAbee J, Åsberg K, & McGee A (2015). Coming out and the potential for growth in sexual minorities: The role of social reactions and internalized homonegativity. Journal of Homosexuality, 62, 1512–1538. 10.1080/00918369.2015.1073032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spengler A (1977). Manifest sadomasochism of males: Results of an empirical study. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 6, 441–456. 10.1007/bf01541150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2019). Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: Results from the 2018 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (HHS Publication No. PEP19–5068, NSDUH Series H-54). Rockville, MD: Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Retrieved from https://www.samhsa.gov/data/ [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick BG, & Fidell LS (2013). Using multivariate statistics (6th ed.). Allyn & Bacon/Pearson Education. [Google Scholar]

- Talley AE, Brown SL, Cukrowicz K, & Bagge CL (2016). Sexual self-concept ambiguity and the interpersonal theory of suicide risk. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 46, 127–140. 10.1111/sltb.12176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker RP (2019). Suicide in transgender veterans: Prevalence, prevention, and implications of current policy. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 14, 452–468. 10.1177/1745691618812680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Orden KA, Cukrowicz KC, Witte TK, & Joiner TE (2012). Thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness: Construct validity and psychometric properties of the Interpersonal Needs Questionnaire. Psychological Assessment, 24, 197–215. 10.1037/a0025358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Orden KA, Witte TK, Cukrowicz KC, Braithwaite SR, Selby EA, & Joiner TE (2010). The interpersonal theory of suicide. Psychological Review, 117, 575–600. 10.1037/a0018697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodward EN, Pantalone DW, & Bradford J (2013). Differential reports of suicidal ideation and attempts of questioning adults compared to heterosexual, lesbian, gay, and bisexual individuals. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Mental Health, 17, 278–293. 10.1080/19359705.2012.763081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright S (2008). Second national survey of violence & discrimination against sexual minorities. Retrieved from https://ncsfreedom.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/Violence-Discrimination-Against-SexualMinorities-Survey.pdf