Abstract

Background: Family Child Care Homes (FCCHs) are the second-largest childcare option in the US. Given that young children are increasingly becoming overweight and obese, it is vital to understand the FCCH mealtime environment. There is much interest in examining the impact of the Child and Adult Care Food Program (CACFP), a federal initiative to support healthy nutrition, by providing cash reimbursements to eligible childcare providers to purchase nutritious foods. This study examines the association among the FCCH provider characteristics, the mealtime environment, and the quality of foods offered to 2–5-year-old children in urban FCCHs and examines the quality of the mealtime environment and foods offered by CACFP participation.

Methods: A cross-sectional design with a proportionate stratified random sample of urban FCCHs by the CACFP participation status was used. Data were collected by telephone using the Nutrition and Physical Activity Self-Assessment for Child Care survey.

Results: A total of 91 licensed FCCHs (69 CACFP, 22 non-CACFP) participated. FCCH providers with formal nutrition training met significantly more of the quality standards for foods offered than providers without nutrition training (β = 0.22, p = 0.034). The mealtime environment was not related to any FCCH provider characteristics. CACFP-participating FCCH providers had a healthier mealtime environment (β = 0.326, p = 0.002) than non-CACFP FCCHs.

Conclusions: Findings suggest that nutrition training and CACFP participation contribute to the quality of nutrition-related practices in the FCCH. We recommend more research on strengthening the quality of foods provided in FCCHs and the possible impact on childhood obesity.

Keywords: childhood obesity prevention, Family Child Care Homes, food deserts, physical food environment

Introduction

Nearly 2 million children less than 5 years of age in the US are in the care of family child care providers, a labor force that provides care for children in licensed home settings outside the child's home, often termed Family Child Care Homes (FCCHs).1 FCCH providers play an essential role in shaping children's food preferences and habits as children spend an average of 35 hours a week in FCCHs, where they consume most of the day's meals and beverages.2,3 Hence, having a better understanding of the relationship between FCCH provider characteristics and their nutrition practices, namely their mealtime environment, which refers to the norms, values, and culture surrounding feeding interactions between providers and children, and the quality of foods offered to young children, can provide the information needed for tailored provider-level interventions to promote children's adoption of healthy eating habits and prevention of obesity. Examples of mealtime best practices in the child care setting include serving meals family-style, role modeling healthy behaviors, praising children for trying new foods, respecting children's satiety, and setting up healthy nonfood reward systems, all while providing a culturally responsive mealtime environment. In a 2018 systematic review examining the obesity-promoting attributes of the FCCH environment, few of the studies reported sociocultural–demographic information, such as the location of FCCHs (i.e., rural, urban), neighborhood-level information, provider race/ethnicity, level of education, household income, language spoken in the FCCH, and adverse social determinants of health.4 Although not widely studied, provider race/ethnicity, level of education, income level, and languages spoken in child care are shown to influence mealtime practices in the childcare setting.5,6

Evidence does not support making generalizations based solely on ethnicity. In one study, Hispanic FCCH providers were more likely to force children to eat,7 cook food that children like,7 and less likely to allow children to determine their satiety6 than non-Hispanic providers. In contrast, another study found that being a Hispanic provider was associated with children consuming high-quality foods compared with non-Hispanic providers.5

FCCH providers' level of education and exhibiting less authoritarian and controlling feeding practices were found to be significantly inversely correlated,8 and FCCH providers were more likely to participate in training related to obesity compared with center-based providers, which consequently led to more FCCH providers than center-based providers engaging in health promotion activities with parents.9

Finally, child care providers participating in the Child and Adult Care Food Program (CACFP), a federal subsidy nutrition program that reimburses child care providers for nutritious food,10 have been shown to have optimal nutrition practices in center-based care. However, less is known about the mealtime environment of CACFP-participating FCCHs.11–14

Understanding the relationships between FCCH provider characteristics and the mealtime environment is critical since the mealtime environment's quality relates to children's consumption of healthy foods.15–22 For example, caregiver role modeling and encouragement during mealtimes positively relate to children's fruit and vegetable intake.15,16 Evidence from center-based child care facilities has shown that provider encouragement is positively associated with children's vegetable intake20 and that children's involvement in food preparation is associated with less intake of sweet snacks20 and greater acceptance of new foods in the absence of peer pressure.21 Providers sharing meals and eating the same foods as children have been associated with higher vegetable intake.22

In FCCHs, an observational study found that although FCCH providers frequently praised the children for trying new foods, they used both positive and coercive controlling feeding practices (i.e., pressuring and threats) when responding to children's verbal and nonverbal refusals and acceptance of food.18 In another study, only 27% of FCCH providers provided meals, family style.19

The purpose of this study was to examine the association among the FCCH provider characteristics, the mealtime environment, and the quality of foods offered to 2–5-year-old children in FCCHs located in a major urban city in the US. We also aimed to examine if the mealtime environment and quality of food varied by CACFP participation. We hypothesized that CACFP-participating FCCHs have a healthier mealtime environment and quality of foods offered best practices scores than non-CACFP-participating FCCHs.

Methods

This study was a cross-sectional telephone survey of licensed FCCH providers.

Study Sample

The Maryland State Department of Education (MSDE), the licensing agency for FCCHs, provided contact information with CACFP status for all licensed FCCH providers operating in Baltimore City, Maryland. We used a proportionate random sampling technique to generate a study sample that reflected the total percentage of CACFP- and non-CACFP-participating FCCHs in Baltimore, City, ∼75% CACFP, and 25% non-CACFP FCCHs.

The study's main goals were to examine the relationship between FCCH provider characteristics (e.g., years of childcare experience, education) with mealtime environment total score and the association between FCCH provider characteristics with quality of foods offered in the FCCH score. We estimated the sample size needed to detect a moderate effect size of 0.30 in a linear regression with the outcome of total mealtime environment score (or total quality of foods offered score) with given provider characteristics as the independent variables using PASS 14.23 With power of 0.80 and alpha = 0.05, we needed an enrollment target of 82 FCCHs to detect a significant correlation of 0.30 or greater.

Participant Recruitment

We sent recruitment letters containing the description of the study and a prestamped return postcard to randomly selected non-CACFP- and CACFP-participating providers. We asked providers to return the postcard within 2 weeks of receipt if they did not wish to be contacted. Follow-up telephone calls were made to those not returning postcards. Eligibility was assessed, and CACFP status was confirmed over the phone. Inclusion criteria for providers were that they operated a licensed FCCH in Baltimore City with at least one participating child 2–5 years of age in full- or half-time care and English fluency. The exclusion criterion was the nonprovision of lunch and snacks to participating children. For those eligible, interested, and consented, we administered the 45-minute survey.

The FCCH providers received a $25 gift card to a local store. Interviews were conducted between August 2015 and April 2017. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine.

Measures

Demographic characteristics

Providers responded to questionnaires with information on their race/ethnicity, height and weight, participation in any nutrition training within the past year (Yes or No), CACFP participation (Yes/No), years of education, years of licensed childcare experience, and the number of children in their care.

Mealtime environment and quality of foods offered scores

We adapted the Nutrition and Physical Activity Self-Assessment for Child Care, Family Child Care Edition (NAP SACC) to measure best practices in the mealtime environment and the nutritional quality of foods offered.24,25 NAP SACC was developed by The University of North Carolina Chapel Hill researchers consulting several regulations and standards for nutrition in childcare settings, including the CACFP. We included 13 of the items that captured the mealtime environment (i.e., role modeling behaviors, respecting satiety, serving meals family style) and 15 items that captured the quality of foods offered (i.e., quality of fruits, vegetables, and beverages provided).

To establish content validity for mealtime environment and quality of foods offered, a panel of three experts (instrument development, child care, and obesity context experts) judged the concordance between the questionnaire items, mealtime environment, and the quality of foods offered. We emailed each reviewer the items from the NAP SACC tool with detailed instructions on rating, including conceptual definitions for mealtime environment and quality of foods offered. Each reviewer rated each item using a 4-point rating scale (1 = not relevant; 2 = unable to assess relevance without item revision or the item requires such revision that it would no longer be relevant; 3 = relevant but needs minor alteration; 4 = very relevant and succinct) as described in Lynn.26

After combining the ratings and feedback and reviewing and seeking clarification from each reviewer by email, revisions were made regarding concerns and comments related to sentence structure, stem-response options not matching the question, grammar, wording of the question (i.e., starting question with “How often”), or replacing leading words such as “healthy” with more specific words such as “dark leafy vegetables, lean meats, and whole grains” to limit responses due to social desirability. Once revisions were made, 100% agreement was achieved to establish content validity across items. No items were removed due to misalignment with the conceptual definition.

Consistent with the scoring protocol used for NAP SACC, we used a 4-point Likert scale (1 = barely met, 2 = met, 3 = exceeded, 4 = far exceeded childcare standards) to signify how nutrition standards were met (see examples in the Supplementary Data).25 All the items for assessing the mealtime environment and the quality of foods offered can be found in Table 2. The final tool consisting of 13 items measuring the quality of the mealtime environment and 15 items measuring the quality of foods offered, was pilot tested with an informal caregiver of nonrelative young children by phone. The NAP SACC-selected items were adapted to suit a structured telephone interview. To avoid repeating multiple response options, we used open-ended questions to ask about the frequency of foods offered and the mealtime environment. Participants' responses were translated to the appropriate response options.

Table 2.

Prevalence of Mealtime Environment and Quality of Foods Offered Exceeding (Score of 3) or Far Exceeding (Score of 4) Child Care Standards by Child and Adult Care Food Program Status (N = 91)

| NAP SACC items |

Total |

CACFP |

Non-CACFP |

p

|

NAP SACC items |

Total |

CACFP |

Non-CACFP |

p

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mealtime environment | Quality of foods offered | ||||||||

| Meals are served family style most or all of the timea | 28% | 33% | 9% | 0.03 | Fruits and vegetables Fruit (not juice) is served ≥1 times per day |

98% | 97% | 100% | 0.42 |

| Provider consumes the same food and drinks as the children often or always | 62% | 65% | 50% | 0.20 | Fruit is served fresh, frozen, or canned in its own juice often or every time fruit is served | 90% | 88% | 96% | 0.33 |

| Provider eats or drinks foods such as soda, chips, cookies, fried foods in front of the children sometimes or rarely/never. | 96% | 94% | 100% | 0.25 | Vegetables (not including French fries or fried potatoes) are served ≥1 time per day | 91% | 94% | 82% | 0.07 |

| Provider's role model healthy eating often or at every meal and snack time | 82% | 86% | 73% | 0.17 | Vegetables that are dark green, red, orange, or yellow in color are served at least 3 times per week.a | 92% | 96% | 82% | 0.03 |

| Providers praise children for trying new or less-preferred foods often or always a | 96% | 99% | 86% | 0.02 | Cooked vegetables are rarely or sometimes served with added meat fat, margarine, or butter. | 81% | 81% | 82% | 0.95 |

| Providers ask children if they are full before removing their plates often or always when children eat less than half of a meal or snack | 75% | 79% | 62% | 0.10 | Fried or prefried potatoes (French fries, tater tots, hash browns) are served <2 times per week. | 65% | 68% | 55% | 0.25 |

| When children request seconds, providers ask if they are still hungry before serving more food most or all of the time. | 55% | 55% | 55% | 0.97 | Meats Fried or prefried meats (chicken nuggets) or fish (fish sticks) are served <2 times per week. |

56% | 53% | 67% | 0.27 |

| Children are required to finish everything on their plate before leaving the meal table sometimes, rarely, or never. | 73% | 68% | 86% | 0.09 | Meets such as sausage, bacon, hot dogs, bologna, ground beef are served <2 times per week. | 69% | 70% | 67% | 0.76 |

| Reason with a child to eat healthy foodsa,b | 49% | 57% | 27% | 0.02 | Meats, such as baked or broiled chicken, turkey, or fish are served ≥3 times per week. | 56% | 57% | 55% | 0.86 |

| Use of children's preferred foods to encourage them to eat vegetables or less-preferred foods | 84% | 84% | 82% | 0.81 | Whole grains Whole grain foods, including whole wheat bread, whole wheat crackers, oatmeal, and brown rice offered ≥1 time per day.a |

66% | 73% | 46% | 0.02 |

| Providers use food to calm upset children sometimes or rarely/never | 95% | 96% | 91% | 0.40 | Foods such as cookies, cakes, doughnuts, pudding, and muffins offered ≤1 time per weeka | 92% | 97% | 76% | 0.002 |

| Hands on help | 87% | 90% | 76% | 0.12 | Beverages 100% fruit juice is served <1 times per day. |

32% | 30% | 36% | 0.60 |

| Providers remind children to drink water during indoor and outdoor playtime often or all of the time | 86% | 88% | 77% | 0.19 | Sugary drinks (Kool-aid™, sports drinks, sweet tea, punches, and soda) other than 100% juice are served only a few times a year or never | 87% | 87% | 91% | 0.62 |

| Milk served to children ≥2 years of age is mostly 1% or skim.a | 55% | 62% | 86% | 0.04 | |||||

| Flavored milk served ≤1 time per week | 91% | 91% | 91% | 0.97 |

Difference in proportions. by CACFP status (χ2) p < 0.05.

Reason = Providing encouragement to children and an explanation on why it is essential to eat healthy foods.

NAP SACC, Nutrition and Physical Activity Self-Assessment for Child Care.

Statistical Analyses

Normality, skewness, kurtosis, box plots, and histograms were assessed, along with prevalence or means and standard deviations (SDs) for each demographic, mealtime environment, and the quality of foods offered. We conducted independent sample t-tests for means and Pearson's chi-square test for Independence (χ2) to examine the differences in demographic characteristics by CACFP status. The outcome variables of total mealtime environment score and quality of food offered score used in the regression were found to follow a normal distribution, so no transformations were applied.

First, to describe the mealtime environment and quality of foods offered, we conducted a series of difference in proportion tests using chi-square (proportion of sample exceeding or far exceeding best practices for each item) to explore if each mealtime environment item and each quality of food offered item differed by CACFP participation. Specifically for this analysis, each item in the adapted NAP SACC tool was dichotomized (best practices reported [score of 3 and 4] vs. best practices not reported [score of 1 and 2]) and summed to create the best practice sum scores for the mealtime environment (13 items) and the nutritional quality of foods offered (15 items) (Table 2).27

We conducted bivariate linear regressions to examine relations between FCCH provider characteristics (years of education, nutrition training, years of experience, number of children 0–23 months, number of children 2–5 years, receiving childcare subsidy, and CACFP participation) with total mealtime environment score and with the quality of foods offered score. Then, we conducted multivariable linear regressions for the total mealtime environment score and the quality of foods offered score, including CACFP participation and adjusting for significant variables at the p = 0.10 level in the bivariate analyses (Table 3). We conducted all statistical analyses using STATA version 14, using p ≤ 0.05 as significant.28

Table 3.

Results of Multivariable Regressions Predicting the Quality of Foods Offered

| β (95% CI) | p | Adjusted R2 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | |||

| Years of education | 0.213 (0.015 to 1.138) | 0.044 | 0.084 |

| Nutrition training | 0.133 (−0.426 to 1.690) | 0.238 | |

| CACFP participation | 0.197 (−0.122 to 1.938) | 0.083 | |

| Model 2 | |||

| Years of education | 0.236 (0.085 to 1.191) | 0.024 | 0.080 |

| CACFP participation | 0.251 (0.213 to 2.101) | 0.017 | |

| Model 3 | |||

| Years of education | 0.174 (−0.085 to 1.026) | 0.096 | 0.062 |

| Nutrition training | 0.212 (−0.030 to 1.988) | 0.043 | |

CI, confidence interval.

Results

Sample

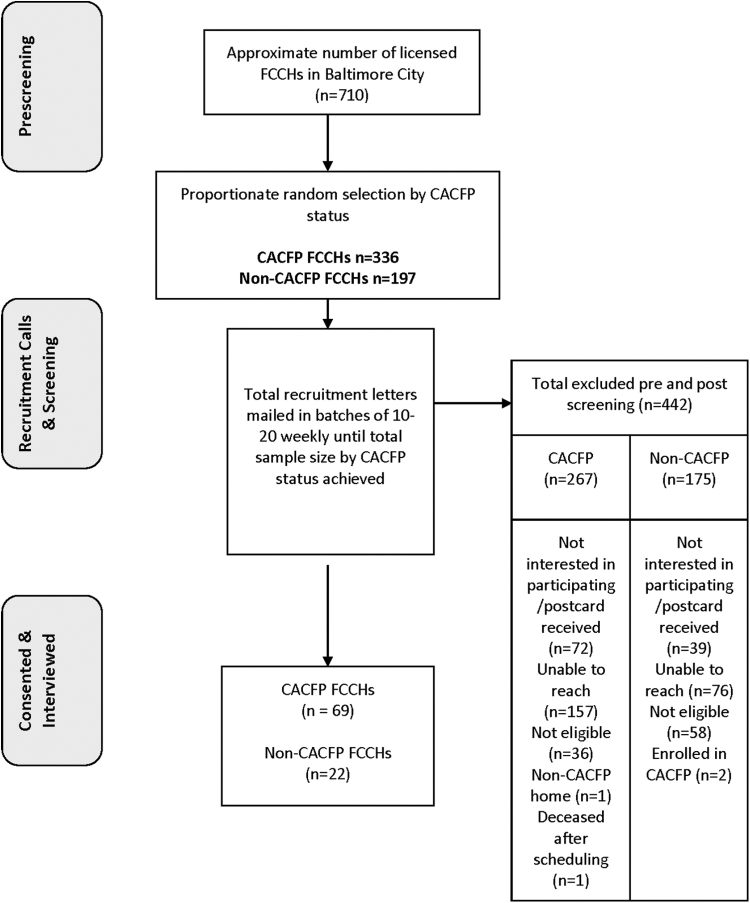

Figure 1 provides a summary of the recruitment process. We mailed 533 recruitment letters, 44% (233) of potential participants were unable to be reached (e.g., incorrect address or phone number, etc.), 21% (111) were not interested in participating and did not participate in eligibility screening, 18% (94) were ineligible, 0.6% (3) CACFP status mismatch, and one participant died after consenting. A total of 91 FCCH providers (69 CACFP and 22 non-CACFP) consented and participated in the phone interview for a response rate of 17%. The majority of the FCCH providers (90%) were Black or African American, with a mean (SD) of 18 (9.5) years of experience and 14.5 (1.7) years of education. Almost half of the providers had obesity (46%), with a mean (SD) body mass index (BMI) of 30 (4.7) kg/m2. There were no significant differences in provider characteristics by CACFP status, with the exception that 87% of CACFP FCCH providers reported having had nutrition training within the past year, compared with 50% of non-CACFP FCCH providers [χ2(1, N = 91) = 13.3, p < 0.001] (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Flowchart describing recruitment efforts. CACFP, Child and Adult Care Food Program; FCCH, Family Child Care Home.

Table 1.

Demographic and Anthropometric Information of Family Child Care Home Providers by the Child and Adult Care Food Program Participation Status (N = 91)

| Total |

CACFP |

Non-CACFP |

CACFP vs. non-CACFP |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (N = 91) |

(n = 69) |

(n = 22) |

||

| N (%) or mean ± SD | p | |||

| aBlack or African American, N (%) | 82 (90) | 63 (91) | 19 (86) | 0.50b |

| Years of education, mean ± SD | 14.5 ± 1.7 | 14.4 ± 0.21 | 14.8 ± 0.33 | 0.54c |

| Educational status, N (%) | 0.73b | |||

| <High school | 1 (1) | 1 (2) | 0 | |

| High school or GED | 32 (35) | 26 (38) | 6 (27) | |

| Some college | 41 (45) | 31 (45) | 10 (46) | |

| ≥College | 16 (18) | 10 (15) | 6 (27) | |

| Years of experience, mean ± SD | 18 ± 9.5 | 18.6 ± 8.8 | 16.1 ± 11.2 | 0.35c |

| Obtained nutrition training within the past year, N (%) | 71 (78) | 60 (87) | 11 (50) | <0.001b |

| BMI kg/m2 mean ± SD | 30 ± 4.7 | 29 ± 4.7 | 31 ± 4.7 | 0.31c |

| Number of children cared for in FCCH, mean ± SD | 5.8 ± 2.4 | 6.0 ± 2.0 | 5.1 ± 3.2 | 0.15 |

| Mealtime environment score, mean ± SD | 9.6 ± 1.6 | 9.9 ± 1.5 | 8.7 ± 1.7 | 0.002c |

| Quality of foods offered score, mean ± SD | 11.1 ± 2.0 | 11.4 ± 1.8 | 10.4 ± 2.3 | 0.051c |

Ethnicity not reported due to too few Hispanics and to protect participant confidentiality.

Pearson's chi-square test for Independence (χ2)

Independent sample t-test for means

Completion of HS or General Education Diploma = 12 years; Some College = 14 years and above.

BMI, body mass index; CACFP, Child and Adult Care Food Program; FCCH, Family Child Care Home; SD, standard deviation.

Prevalence of Mealtime Environment and Quality of Foods Offered Best Practices by CACFP Status

Table 2 provides the prevalence of FCCH providers who reported best practices (score of 3 or 4) for mealtime environment and nutrition (quality of foods offered) by CACFP participation. Regarding the mealtime environment, although 24% more CACFP than non-CACFP providers served meals family style, fewer than 50% of all the FCCHs in this study served meals family style most or all the time. Additionally, compared with non-CACFP providers, significantly more CACFP providers (86% vs. 99%) praised children for trying new foods and reasoned with their child to eat healthy foods often or always, meaning providers provided a reason or explanation on why certain foods were healthy and encouraged children to eat healthy foods (27% vs. 57%). Regarding the quality of the foods offered, 87% of providers did not provide sugary drinks such as sweet tea and soda, but more than 50% of CACFP and non-CACFP homes provided 100% juice more than once a day. Compared with CACFP homes, fewer non-CACFP providers frequently offered whole-grain foods (73% vs. 46%) and dark vegetables (96% vs. 82%), but more non-CACFP infrequently served high-fat/high-sugar foods and mainly served 1% or skim milk.

Relationship of FCCH Provider Characteristics with Mealtime Environment and Quality of Foods Offered Best Practices

Mean scores for the mealtime environment and the quality of foods offered on the number of standards met were normally distributed with means of 9.62 (SD = 1.62, range 5–12 of a possible 13) and 11.13 (SD = 2.09, range = 3–15 of a possible 15), respectively.

In unadjusted bivariate linear regression models, the quality of the mealtime environment was not related to any of the FCCH provider characteristics; years of childcare experience (p = 0.162), years of education (p = 0.917), formal nutrition training within the past year (p = 0.505), BMI (p = 0.970), number of children 0–23 months (p = 0.584), number of children 2–5 years (p = 0.301), number of children 5+ years (p = 0.669), and receiving childcare subsidy (p = 0.412).

In unadjusted bivariate linear regression models, the quality of foods offered was not related to years of childcare experience (p = 0.908), BMI (p = 0.369), number of children 0–23 months (p = 0.508), number of children 2–5 years (p = 0.539), number of children 5+ years (p = 0.854), or receiving childcare subsidy (p = 0.184). However, years of education (p = 0.063) was associated at alpha = 0.10 level with those who had more education offering more quality foods. Providers with formal nutrition training within the past year had met significantly more of the quality standards for foods offered than those without nutrition training (β = 0.22, 95% confidence interval, CI [0.08–2.05, p = 0.034]).

CACFP Status, Mealtime Environment, and Quality of Foods Offered Best Practices

While the CACFP homes had higher quality of food scores (M = 11.36, SD = 1.83) than non-CACFP homes (10.41, SD = 2.32), the difference did not reach statistical significance [t(89) = −1.98, p = 0.051]. To examine the relative importance of the provider characteristics in quality of food offered, we used multivariable linear regressions to predict the quality of foods offered, based on provider years of education, CACFP participation, and nutrition training of FCCH providers (Table 3). Only provider years of education were significant (β = 0.213, 95% CI [0.12–1.14], p = 0.004). The model had an adjusted R2 of 0.08 [F(3, 86) = 3.72, p = 0.014]. CACFP participation and nutrition training were moderately correlated (r = 0.382, p < 0.001) using Cohen's effect size standards,29 indicating some multicollinearity. To investigate their joint association further, nutrition training was not included in the multivariable regression and provider years of education remained significant (β = 0.236, 95% CI [0.09–1.19], p = 0.024), as did CACFP participation (β = 0.251, 95% CI [0.21–2.10], p = 0.017), and the adjusted R2 remained at 0.08. However, when CACFP participation instead of nutrition training was dropped from the model, nutrition training was significant (β = 0.212, 95% CI [0.03–1.99], p = 0.043), although the adjusted R2 dropped to 0.06. CACFP status appears to contribute more to the quality of food offered than having formal nutrition training as it accounts for more variance in the multivariable model than nutrition training.

Mealtime environment mean scores were higher for CACFP homes (M = 9.91, SD = 1.48) compared with non-CACFP homes [M = 8.58, SD = 1.73; t(89) = −3.26, p = 0.002]. Since none of the FCCH provider characteristics was associated with the mealtime environment, we did not conduct a multivariable regression. The final model had CACFP participation as the sole significant predictor (β = 0.326, 95% CI [0.48–1.98], p = 0.002) with an adjusted R2 of 0.10.

Discussion

Our FCCH study provides important information about the mealtime environment and the quality of foods offered in urban FCCHs, and the impact of CACFP participation. We show that in a sample of FCCH providers, the mealtime environment best practices were not related to any of the provider characteristics. Providers who obtained nutrition training within the past year met significantly more best practices for foods offered than those that did not have training. Furthermore, we found that CACFP and nutrition training were positively related, suggesting that CACFP participating FCCH providers were also more likely to have had nutrition training within the past year.

Overall, our results demonstrate that provider nutrition training enhances the quality of foods provided in the FCCH. Although it is not clear whether providers obtain nutrition training every year through the CACFP since yearly training covers many different topics,30 nor is yearly nutrition training mandated by the MSDE independent of the CACFP.31 CACFP-participating providers were more likely to have received nutrition training within the past year. In a similar study conducted in Maryland's center-based childcare,27 provider nutrition training was positively associated with feeding environment best practices when considered among several center demographics, including whether the center participated in the CACFP, served majority Caucasian or African American children, the center size, and center policies. Despite these findings on nutrition training, barriers such as scheduling conflicts, access, and prohibitive costs, persist among childcare providers to obtaining nutrition training.32 Flexible training programs that are virtual and low cost can alleviate some of these barriers. Additionally, mandatory nutrition training among all providers seeking licensure has the potential to improve nutrition practices in the FCCH.

In support of our hypothesis, CACFP-participating FCCHs had significantly higher mealtime environment mean scores than non-CACFP FCCHs. Additionally, compared with non-CACFP providers, more CACFP FCCH providers reported having exceeded or far exceeded child care standards in serving meals family style. Family-style dining is supported as a mealtime best practice because it gives providers the opportunity to role model healthy eating and equips children with social skills around the table. Recent evidence shows that delivering meals family style, instead of preplating or preportioning foods, was associated with lower levels of food restriction33 and may prevent children from overeating.34 More research is needed in exploring the presence of family-style dining in FCCHs.

Although we found that significantly more CACFP than non-CACFP FCCHs provided meals family style, only 9% non-CACFP and 33% CACFP providers reported serving meals family style most or all of the time. In one study, only 27% of FCCH providers provided meals family style.19 Implementing quality family-style dining will affect healthy nutrition practices among providers and improve parent engagement in the FCCH.35 Additional mealtime environment findings in this study include CACFP providers praising children for trying new foods and reasoning or encouraging children to eat healthy foods, both nutrition best practices.

Inconsistent with our hypothesis, the quality of food scores did not significantly differ by CACFP status, despite CACFP providers having a higher quality of food offered scores than non-CACFP providers. However, fewer non-CACFP homes served high-fat/high-sugar foods and served mostly 1% or skim milk. This finding contradicts a study finding conducted in a southern state that showed that CACFP FCCHs were significantly more likely to serve Skim or 1% milk than non-CACFP FCCHs.36 More than 50% of CACFP and non-CACFP homes provided 100% juice more than once a day. This practice is consistent with other findings, which reported that more than half of FCCH providers offered 100% fruit juice 3–4 times weekly.37

Updated Meal Pattern Guidelines for CACFP

By the end of this study's data collection, the Food and Nutrition Service published the final rule for new CACFP meal patterns. It gave early care and education programs until October 1, 2017, to align their nutrition practices with the new meal pattern guidelines.19,38 Additional follow-up studies are needed to examine the success of implementing the new meal patterns in the FCCH.

Strengths and Limitations

There were several limitations to this study. First, because this was a cross-sectional survey, we are unable to determine causality. Potential biases included the willingness to participate in a study, exclusively self-reported data, and the possibility of providing socially desirable responses. To minimize biases, we emphasized that all data would be deidentified and reported in aggregate. Providers were also assured that data were confidential and would not be shared with anyone, including the MSDE. All FCCHs were located within an urban city, limiting the generalizability of our results. However, we strengthened the research design by utilizing a proportionate random stratified sampling approach to accurately reflect the CACFP and non-CACFP providers in the study population.

Despite the study limitations, this survey examines the food environment of FCCHs in a major urban city where more than 20% of its residents live in urban poverty, and more than 60% of its residents are Black or African American. Our study provides unique contributions to the field of FCCH research. We show that the CACFP can be instrumental in fostering a positive mealtime environment in FCCHs. These findings suggest that CACFP's impact could be increased by ensuring that the childcare provider training is centered on what and how food are offered to children in FCCHs.

Conclusion

Nutrition Training and CACFP support to FCCHs helps to promote the best nutrition practices in the FCCH. CACFP providers receive financial assistance and are routinely audited to reinforce best practices within the FCCH.10 Strengthening the CACFP to include training materials on the mealtime environment and recruiting more FCCH providers into the CACFP may improve mealtime interactions between providers and children. Due to newly sanctioned CACFP guidelines, future studies on implementing the new CACFP guidelines in FCCHs is a necessary next step. Finally, developing interventions unique to FCCHs in urban settings would help providers offer the best possible environment for young children living in low-resourced communities.

Supplementary Material

Authors' Contributions

L.F., M.B., and J.A. have made substantial contributions to the conception of the study, and all authors (L.F., N.P., M.B., and J.A.) drafted the article or revised it critically for important intellectual content. Additionally, N.P. provided additional statistical support for data analyses.

Funding Information

This study was supported by the NIH/NINR F31 NR015399, Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award, and the NIH/NINR T32 NR012704, Predoctoral Fellowship in Interdisciplinary Cardiovascular Health Research. The content does not reflect the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1. Laughlin L. Who's Minding the Kids? Child Care Arrangements: Spring 2011. Household Econ Stud 2013;2009:70–135. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Story M, Kaphingst K, French S. The role of child care settings in obesity prevention. Future Child 2006;16:143–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. ChildCare Aware of America. About Child Care. 2019. Available at childcareaware.org. http://usa.childcareaware.org/families-programs/about-child-care/.

- 4. Francis L, Shodeinde L, Black MM, Allen J. Examining the obesogenic attributes of the family child care home environment: A literature review. J Obes 2018;2018:3490651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Tovar A, Risica PM, Ramirez A, et al. . Exploring the provider-level socio-demographic determinants of diet quality of preschool-aged children attending family childcare homes. Nutrients 2020;12:1368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gans KM, Tovar A, Jiang Q, et al. . Nutrition-related practices of family child care providers and differences by ethnicity. Childhood Obes 2019;15:167–184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Freedman MR, Alvarez KP. Early childhood feeding: Assessing knowledge, attitude, and practices of multi-ethnic child-care providers. J Am Diet Assoc 2010;110:447–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Brann LS. Child-feeding practices and child overweight perceptions of family day care providers caring for preschool-aged children. J Pediatr Health Care 2010;24:312–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kim J, Shim JE, Wiley AR, et al. . Is there a difference between center and home care providers' training, perceptions, and practices related to obesity prevention? Matern Child Health J 2012;16:1559–1566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. United States Department of Agriculture. Available at www.fns.usda.gov. https://www.fns.usda.gov/cacfp/child-and-adult-care-food-program Last accessed January 10, 2017.

- 11. Liu ST, Graffagino CL, Leser KA, et al. . Obesity prevention practices and policies in child care settings enrolled and not enrolled in the child and adult care food program. Matern Child Health J 2016;20:1933–1939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ritchie LD, Boyle M, Chandran K, et al. . Participation in the child and adult care food program is associated with more nutritious foods and beverages in child care. Childhood Obes 2012;8:224–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Zaltz DA, Hecht AA, Pate RR, et al. . Participation in the Child and Adult Care Food Program is associated with fewer barriers to serving healthier foods in early care and education. BMC Public Health 2020;20:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hasnin S, Dev DA, Tovar A. Participation in the CACFP Ensures Availability but not Intake of Nutritious Foods at Lunch in Preschool Children in Child-Care Centers. J Acad Nutr Diet 2020;120:1722–1729.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Pearson N, Biddle SJ, Gorely T. Family correlates of fruit and vegetable consumption in children and adolescents: A systematic review. Public Health Nutrition 2009;12:267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. McGowan L, Croker H, Wardle J, Cooke LJ. Environmental and individual determinants of core and non-core food and drink intake in preschool-aged children in the United Kingdom. Eur J Clin Nutr 2012;66:322–328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. McCurdy K, Gorman KS, Kisler T, Metallinos-Katsaras E. Associations between family food behaviors, maternal depression, and child weight among low-income children. Appetite 2014;79:97–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Tovar A, Vaughn AE, Fallon M, et al. . Providers' response to child eating behaviors: A direct observation study. Appetite 2016;105:534–541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Trost SG, Messner L, Fitzgerald K, Roths B. Nutrition and physical activity policies and practices in family child care homes. Am J Prev Med 2009;37:537–540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gubbels JS, Gerards SMPL, Kremers SPJ. Use of food practices by childcare staff and the association with dietary intake of children at childcare. Nutrients 2015;7:2161–2175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hendy HM. Effectiveness of trained peer models to encourage food acceptance in preschool children. Appetite 2002;39:217–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kharofa RY, Kalkwarf HJ, Khoury JC, Copeland KA. Are mealtime best practice guidelines for child care Centers Associated with Energy, Vegetable, and Fruit Intake? Child Obes 2016;12:52–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. PASS 2020 Power Analysis and Sample Size Software. 2020. Available at ncss.com/software/pass.

- 24. Benjamin SE, Neelon B, Ball SC, et al. . Reliability and validity of a nutrition and physical activity environmental self-assessment for child care. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2007;4:61–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ammerman AS, Ward DS, Benjamin SE, et al. . An intervention to promote healthy weight: Nutrition and Physical Activity Self-Assessment for Child Care (NAP SACC) theory and design. Prev Chronic Dis 2007;4:A67. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. LYNN MR. Determination and quantification of content validity. Nurs Res 1986;35:382–386. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bussell K, Francis L, Armstrong B, et al. . Examining nutrition and physical activity policies and practices in Maryland's child care centers. Childhood Obes 2018;14:403–411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 14. 2015.

- 29. Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. New York, New York: Routledge Academic, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Family League of Baltimore. Child and Adult Care Food Program Providing Food, Education, and Services to Children in Care. Available at https://www.familyleague.org/food-access/#1550201868404-17cf228a-ef00 Last accessed September 2, 2021.

- 31. Maryland State Department of Education. What is a Family Child Care Provider? Available at https://earlychildhood.marylandpublicschools.org/child-care-providers/family-child-care-providers Last accessed September 2, 2021.

- 32. Dev DA, Garcia AS, Tovar A, et al. . Contextual factors influence professional development attendance among child care providers in Nebraska. J Nutr Educ Behav 2019;52:270–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Loth KA, Horning M, Friend S, et al. . An exploration of how family dinners are served and how service style is associated with dietary and weight outcomes in children. J Nutr Educ Behav 2017;49:513–518.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Fisher JO, Rolls BJ, Birch LL. Children's bite size and intake of an entrée are greater with large portions than with age-appropriate or self-selected portions. Am J Clin Nutr 2003;77:1164–1170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Garcia AS, Dev DA, Stage VC. Predictors of parent engagement based on child care providers' perspectives. J Nutr Educ Behav 2018;50:905–912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Erinosho T, Vaughn A, Hales D, et al. . Participation in the child and adult care food program is associated with healthier nutrition environments at family child care homes in Mississippi. J Nutr Educ Behav 2018;50:441–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Tandon PS, Garrison MM, Christakis DA. Physical activity and beverages in home- and center-based child care programs. J Nutr Educ Behav 2012;44:355–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. United States Department of Agriculture. Child and Adult Care Food Program: Meal Pattern Revisions Related to the Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act of 2010; Final Rule. Washington, DC, 2016. https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/FR-2016-04-25/pdf/2016-09412.pdf. [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.