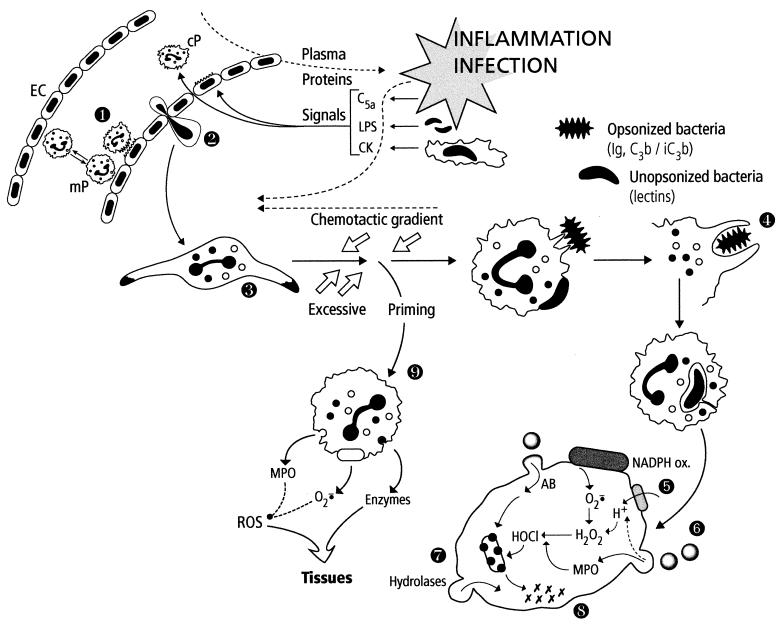

FIG. 2.

Summary of PMN functions. The localized inflammation following pathogen invasion generates many activating signals for endothelial cells (EC) and circulating PMNs (cP). Concomittant activation of these cells results in strong binding of PMNs to EC (step 1) and later in their transendothelial migration (diapedesis) (step 2). PMNs are attracted to the infected area (oriented migration, chemotaxis) along the chemotactic gradient (step 3). During their voyage, PMNs are primed by various signals (cytokines [CK], LPS, etc.) and are thus prepared to perform their bactericidal function. PMNs recognize pathogens via their membrane receptors for the Fc of immunoglobulins (Ig) or complement proteins (C3b/iC3b) or via lectins. The adherent pathogen is engulfed (phagocytosis) (step 4) in a vacuole. The contents of specific and azurophilic granules are released into the phagosome, which becomes a phagolysosome (degranulation, exocytosis) (step 6), parallel to the activation of the NADPH oxidase system initiating the oxidative burst (step 5). Oxygen-dependent and -independent (natural protein and peptide antibiotics [AB]) bactericidal systems cooperate to destroy the pathogen (step 7). The last step corresponds to the digestion of the bacterial debris by hydrolases and other lytic enzymes released in the phagolysosome (step 8). In the setting of excessive priming, PMNs stop migrating and the activation (degranulation, production of reactive oxygen species [ROS]) takes place in the tissues, which can be injured (step 9).