Abstract

Objectives

Ki-67, a marker of cellular proliferation, is associated with prognosis across a wide range of tumours, including gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms (NENs), lymphoma, urothelial tumours and breast carcinomas. Its omission from the classification system of pulmonary NENs is controversial. This systematic review sought to assess whether Ki-67 is a prognostic biomarker in lung NENs and, if feasible, proceed to a meta-analysis.

Research design and methods

Medline (Ovid), Embase, Scopus and the Cochrane library were searched for studies published prior to 28 February 2019 and investigating the role of Ki-67 in lung NENs. Eligible studies were those that included more than 20 patients and provided details of survival outcomes, namely, HRs with CIs according to Ki-67 percentage. Studies not available as a full text or without an English manuscript were excluded. This study was prospectively registered with PROSPERO.

Results

Of 11 814 records identified, seven studies met the inclusion criteria. These retrospective studies provided data for 1268 patients (693 TC, 281 AC, 94 large cell neuroendocrine carcinomas and 190 small cell lung carcinomas) and a meta-analysis was carried out to estimate a pooled effect. Random effects analyses demonstrated an association between a high Ki-67 index and poorer overall survival (HR of 2.02, 95% CI 1.16 to 3.52) and recurrence-free survival (HR 1.42; 95% CI 1.01 to 2.00).

Conclusion

This meta-analysis provides evidence that high Ki-67 labelling indices are associated with poor clinical outcomes for patients diagnosed with pulmonary NENs. This study is subject to inherent limitations, but it does provide valuable insights regarding the use of the biomarker Ki-67, in a rare tumour.

Prospero registration number

CRD42018093389.

Keywords: respiratory tract tumours, pathology, endocrine tumours

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This systematic review and meta-analysis provides a comprehensive synopsis of the literature published up to February 2019.

The protocol adheres to Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis guidelines and was published in the BMJ Open ensuring transparency.

Heterogeneity in methodologies, diverse cohort sizes and types and variety of endpoints considered may limit comparison across studies.

Introduction

Bronchopulmonary neuroendocrine neoplasms (NENs) encompass a group of malignancies, which exhibit considerable diversity and behave in an extremely heterogeneous manner. Pulmonary NENs are classified through a combination of morphological neuroendocrine characteristics together with additional histological parameters by the 2015 WHO classification.1 This classification separates pulmonary NENs into four distinct groups ranging from typical and atypical carcinoids (ACs)to large cell neuroendocrine carcinomas (LCNECs) and small cell lung carcinomas (SCLCs). Typical carcinoids (TCs) are well differentiated, slow growing, indolent tumours which rarely metastasise. By way of contrast, SCLCs are aggressive, poorly differentiated tumours, which have frequently metastasised at the point of presentation. Clinical outcomes are also markedly different; the 10-year survival for TCs is reported to be 82%–87%, while the prognosis for untreated metastatic small cell lung cancer is 6–12 weeks.2–4

Originally identified in the 1980s by Gerdes et al, the DNA binding nuclear protein, Ki-67, is expressed during all phases of the cell cycle barring the rest phase (G0).5 MKI67, the gene that encodes the Ki-67 protein is located on chromosome 10q26.6 While a number of studies initially implicated Ki-67 in ribosomal RNA synthesis, more recent evidence suggests that its main role is as a biological surfactant to disperse mitotic chromosomes.7 In the setting of malignancy, Ki-67 has become established as a robust biomarker of cellular proliferation given its characteristic property of being rapidly degraded during anaphase and telophase with a short half life of 1–1.5 hours. Across multiple tumour sites, numerous studies have determined an association between the Ki-67 LI and patient survival.8–12 Furthermore, evidence in other solid tumours suggests that Ki-67 is also a useful predictive biomarker, predicting response to treatment such as chemotherapy; in gastroenteropancreatic NENs (GEP-NENs) Ki-67 LI is not only integral to grading and classification but subsequently also assists oncologists to determine how best to sequence treatments for patients.

Pulmonary NENs are classified on the basis of morphological characteristics, including mitotic activity and the presence or absence of necrosis (2015 WHO classification). As outlined above, they are stratified into the well-differentiated NETs (TC and ACs) and the poorly differentiated NECs (LCNECs and SCLCs). Despite each of these subtypes being endowed with behavioural heterogeneity, these tumours are not further subcategorised according to tumour grade.13 This places pulmonary NENs at odds with GEP-NENs, where the Ki-67 index together with the mitotic rate are important considerations when determining the grade of disease and also significantly influences how therapies are sequenced. The updated 2019 WHO classification of digestive NENs has progressed further, by formally recognising the heterogeneity of grade 3 NENs—a well-differentiated grade 3 NET group has been included for the first time differentiated them from their poorly differentiated counterparts.14

While a number of studies have been conducted to examine the prognostic utility of Ki-67 in pulmonary NENs, its omission from the pulmonary NEN classification system remains controversial. No consensus has been established for the routine use of Ki-67 in pulmonary NENs. Nevertheless, oncologists continue to request this in the belief that this marker is predictive and/or prognostic.15 Therefore, the primary aim of this systematic review and meta-analysis is to determine whether existing evidence supports or refutes the use of Ki-67 as a prognostic biomarker in pulmonary NENs.

Methods

This study was prospectively registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) website following the production of a protocol in accordance with Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. A copy of the PRISMA protocol is also available via the BMJ Open.16

Search strategy and selection criteria

A systematic review was conducted evaluating the prognostic relevance of the Ki-67 LI in patients with bronchopulmonary NENs. MEDLINE Ovid, Embase, the Cochrane Library and Scopus were searched to look for relevant studies published from the inception of each database to 28 February 2019. The following search terms were employed: ‘Ki-67’, ‘mib-1’, ‘neuroendocrine tumor, ‘carcinoid’ and ‘small cell lung carcinoma’. References of articles included in the analysis were also screened to ensure a complete data set that was available for review. An example of the full-search strategy is available in online supplemental file 1.

bmjopen-2020-041961supp001.pdf (54.5KB, pdf)

To be eligible, studies had to provide details of prognostic outcomes (HRs with CIs or 5-year overall survival (OS)) in more than 20 subjects with pulmonary NENs according to Ki-67 LI. Studies that did not provide sufficient prognostic details for the pulmonary NEN cohort, studies not published in English or not available as a full manuscript were excluded. Articles that contained only predictive outcomes were also excluded.

Two independent reviewers (SN and CH) screened the title and abstracts against the predefined eligibility criteria independently of each other. Where discrepancies arose, a third reviewer (GP) served as arbitrator and a collective decision was then reached. Data from the studies were extracted (SN) and reviewed (GP).

Data analysis

For each study included in the meta-analysis, the following study characteristics were extracted wherever possible: first author, year of publication, country where the study was carried out, study design, number of patients, histological subtypes, mean age, disease stage, gender distribution, length of follow-up and methodology for calculating Ki-67. HRs with 95% CIs were sought as the primary outcome measure from each study in terms of OS, disease-free survival (DFS) and recurrence-free survival (RFS). Secondary outcomes for each study were 5-year survival rates. DFS denotes the length of time between primary treatment and first relapse, whereas RFS refers to the time between primary treatment and local or regional relapse.

The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (as recommended by the Cochrane Non-Randomised Studies Methods Working Group) was utilised to appraise the quality of studies eligible for meta-analysis.17 This involved appraising the selection, comparability and outcome of each study with scores ranging from 0 to 9. Scores of 0–3 indicate a low-quality study, 4–5 and 6–9 are considered medium and high quality, respectively. Only medium and high-quality studies were considered for inclusion in the meta-analysis.

Statistical analysis

The statistical analyses were performed using the RevMan V.5.3 software (Cochrane Collaboration, Copenhagen, Denmark). The generic inverse variance model was employed to pool and weight HRs. In order to assess the heterogeneity of results between studies, Higgins I2 statistic was used. Where there was evidence of high levels of heterogeneity (ie, I2 >50%), a random-effects model was utilised. It was intended to assess the risk of bias using funnel-plot visual inspections together with Begg’s and Egger’s test.

Role of the funding source

There was no funding source for this study. The corresponding author had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Results

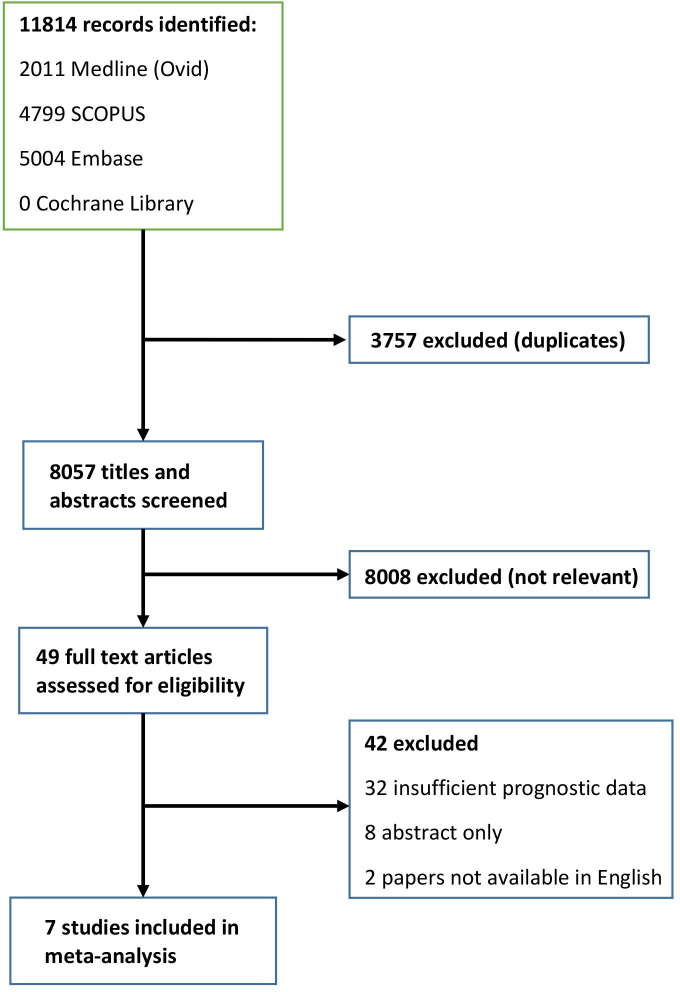

The database searches identified 11 814 publications. Following the exclusion of duplicates, 8057 studies remained. 8008 articles were excluded following initial screening of titles and abstracts. The remaining 49 articles were retrieved for full-text review. Fourty-two further articles were excluded, with the main reason for exclusion being insufficient prognostic data to facilitate a meta-analysis. A flowchart of the study selection process is shown in figure 1. Although the planned protocol had intended to also capture 5-year survival data, due to the heterogeneity of Ki-67 cut-offs utilised and data presentation via Kaplan-Meier curves, it was not possible to present this in a meaningful way. This was due to the 5-year survival estimates not being reported in all studies and could only be detected through Kaplan-Meier plots.

Figure 1.

Study selection.

Study characteristics and quality evaluation

Seven papers, published between 2013 and 2018 including 1268 patients (693 TC, 281 AC, 94 LCNEC and 190 SCLC), fulfilled the inclusion criteria for meta-analysis.18–24 All included studies were retrospective and observational in nature, with no prospective studies identified. The cohort sizes varied between 82 and 399 subjects. Only one study (Rindi et al) was inclusive of the full range of pulmonary NENs with most studies only including the well-differentiated NETs (TCs and ACs). Four of the studies included Italian cohorts, with France, Brazil, Finland and the UK each contributing a single study. The majority of studies used the MIB-1 antibody (4 of 7), although not all studies provided this information.

The majority (76.8%) of the patients had well-differentiated tumours (either in the form TC or AC) with only a minority (23.1%) having poorly differentiated NECs. Fifty-one per cent of the participants were women. The age range of participants varied between 15 and 83 years with one study failing to provide this information. Three studies did not report data for tumour stage. Across the remaining four studies, the majority of participants were noted to have early stage disease (54.3% of patients had stage I disease, 15.5% stage II, 14.2% stage III, 13.8% stage IV, 4.2% stage X). Median length of follow-up ranged between 9.6 and 70 months. The population characteristics of studies included in the meta-analysis are summarised in table 1.

Table 1.

Main characteristics of all studies included in the meta-analysis

| Author (year) | Trial design (study centres) | Number of subjects | Histological subtypes | Age range | Gender M:F |

Stage | Antibody | Methodology for calculating Ki-67 | Median length of follow-up (months) | Ki-67 cut-off thresholds (%) | Outcome measure | HR (95% CI) from univariate analyses |

| Cusumano et al (2017)18 | Retrospective multicentre study (France, Italy) | 195 | TC (159); AC (36) | 52.94 (TC); 60.16 (AC) (mean values) | 89:106 | I=163; II=16; III=16; IV=0 | NR | NR | 75 (mean) | NR | OS (Death HR) DFS |

1.07 (0.97 to 1.17) 0.97 (1.01 to 1.2) |

| Rego et al (2017)24 | Retrospective, multicentre study (Brazil) | 82 | SCLC (82) | 35–81 (mean 59) | 48:34 | I=0; II=0; III=6; IV=76 | MIB-1 (1:1000) | Hotspot method; otherwise not specified | 10.3 | 55 | OS | 1.15 (0.70 to 1.89) |

| Marchio et al (2017)20 | Retrospective multicentre study (Italy) |

239 | TC (171); AC (68) | NR | 100:139 | NR | NR | Manual counting of >1000 cells | NR | 4 | OS TTP |

4.31 (1.624 to 11.45) 3.994 (1.58 to 10) |

| Filosso et al (2013)21 | Retrospective, single centre study (Italy) | 126 (NB 110 included in Ki-67 analysis) | TC (83); AC (43).(In Ki-67 analysis TC (79); AC (31)) | 15–82 (mean 60) | 52:74 | I=90; II=18; III=16; IV=2; X=1 | Anti–Ki-67 antibody (DAKO) not further specified |

NR | 60 | 6 | OS | 2.08 (1.02 to 4.27) |

| Rindi et al (2014)23 | Retrospective, multicentre study (Italy) | 399 | TC (113); AC (84); LCNEC (94); SCLC (108) | 63.26 (median) | 245:154 | I=183; II=90; III=76; IV=17; X=33 | MIB-1 antibody | Computer-assisted manual count method 500–2000 cells | 70.72 | <4 vs 4–20 | OS | 1.26 (0.84 to 1.89) |

| Clay et al (2017)22 | Retrospective, single centre study (UK) | 94 (NB survival analysis performed on 84) | TC (75); AC (19) (NB survival analysis performed 67 TC, 17 AC patients) | 21–83 (median 60.5) | 39:55 | NR | MIB-1 antibody (1:50) | Manual count method 500–2000 cells in hot spot | 35 | NR | RFS | 1.47 (1.25 to 1.74) |

| Vesterinen et al (2018)19 | Retrospective, single centre study (Finland) | 133 (129 included in Ki-67 analysis) | TC (100); AC (33) | 47:86 | NR | MIB-1 antibody (1:100) | Manual and automated counting of 2000 cells | 9.6 | 2.5 | Disease-specific mortality | 10.51 (2.12 to 52.13) |

DFS, disease free survival; F, female; M, male; NR, not recorded; OS, overall survival; RFS, recurrence free survival; TTP, time to progression.

Quality evaluation revealed that the studies included in the meta-analysis were of an overall good quality. The median Newcastle-Ottawa Scale score was 7, with three papers scoring 7 and 8 each and one scoring 6 (table 2). Five and three studies made HR and CI data available for OS and RFS, respectively.

Table 2.

Quality assessment of included studies utilising the (modified) Newcastle-Ottawa Scale

| Author (year) | Representativeness of cohort (one point) |

Adequate definition of cases (one point) |

Assessment of exposure (one point) |

Outcome of interest not present at start of study (one point) |

Comparibility on the basis of the design or analysis (two points) |

Assessment of outcome (death or recurrence) (one point) |

Adequacy of median follow-up for outcome (>2 years) (one point) |

Adequacy of follow-up of cases (<20% or reported) (one point) |

Total quality score |

| Cusumano et al (2017)18 | ✰ | ✰ | ✰ | – | ✰✰ | ✰ | ✰ | ✰ | 8 |

| Rego et al (2017)24 | ✰ | ✰ | ✰ | – | ✰ | ✰ | – | ✰ | 6 |

| Marchio et al (2017)20 | ✰ | ✰ | ✰ | – | ✰✰ | ✰ | – | ✰ | 7 |

| Filosso et al (2013)21 | ✰ | ✰ | ✰ | – | ✰✰ | ✰ | ✰ | ✰ | 8 |

| Rindi et al (2014)23 | ✰ | ✰ | ✰ | – | ✰✰ | ✰ | ✰ | ✰ | 8 |

| Clay et al (2017)22 | ✰ | ✰ | ✰ | – | ✰ | ✰ | ✰ | ✰ | 7 |

| Vesterinen et al (2018)19 | ✰ | ✰ | ✰ | – | ✰✰ | ✰ | – | ✰ | 7 |

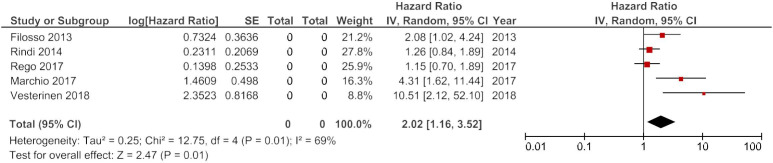

Meta-analysis of OS

In the meta-analysis of OS, five studies were included (Cusumano et al published a death HR, while Vesterinen et al offered a HR for disease specific mortality—both were deemed to be surrogate markers of OS).17 18 HRs derived from univariate analyses were considered for meta-analysis over their multivariate counterparts in an effort to limit the heterogeneity, resulting from how HRs are derived. The heterogeneity was high: I2=69%. This necessitated the use of a random-effects model. The pooled HR for Ki-67 was 2.02 (95% CI 1.16 to 3.52) with a p value of 0.01 (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Forest plot of studies evaluating the association between Ki-67 expression and overall survival in pulmonary neuroendocrine neoplasms.

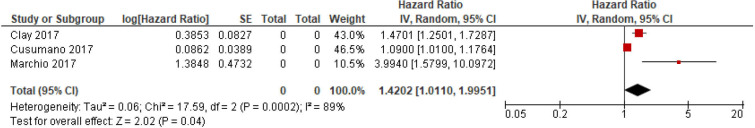

Meta-analysis of RFS

In the meta-analysis of RFS, three studies were available (in one recurrence, HR was available while a second study provided a time to progression HR—both were considered to be surrogate markers of RFS). Once again, the heterogeneity was high (I2=89%) and, therefore, a random-effects model was appropriate. The pooled HR was 1.42 (95% CI 1.01 to 2.00; p 0.04) (figure 3).

Figure 3.

Forest plot of studies evaluating the association between Ki-67 expression and recurrence-free survival in pulmonary neuroendocrine neoplasms.

Risk of bias

Despite the intention to assess the risk of bias using funnel-plot visual inspections, Begg’s and Egger’s test, this was not feasible due to the low number of studies included in the meta-analysis.

Discussion

Prognostic biomarkers and tools play an important role in oncological management and decision-making processes. In pulmonary NENs, the dearth of prognostic biomarkers is notable and, therefore, oncologists often request Ki-67 indices in order to assist in therapeutic decisions despite the fact that this has not been formally adopted. The primary aim of this study was to evaluate whether existing Ki-67 LI is associated with prognosis in pulmonary NENs as has been demonstrated in numerous other tumour types (eg, GEP-NENs, urothelial carcinomas, breast cancer, lymphoma and lung cancer).

Ki-67 is most frequently evaluated immunohistochemically on paraffin sections using the MIB-1 antibody. Scoring is generally formulated by the percentage of tumour cells stained positively to the antigen (also known as the labelling index (LI)). Several methods are available to evaluate the Ki-67 LI, including digital image analysis, eyeball estimation and manual counting. In digestive NENs, the method currently considered ‘gold standard’ is to evaluate the area with the most dense Ki-67 staining (ie, histological ‘hotspots’) and to subsequently manually count a minimum of 500 cells, with best practice being to count 2000 cells or 2 mm2.25 26 Manual counting is subjected to limitations—not only it can become tedious, but it is time-consuming as counting 2000 cells can take approximately 40 min to complete. Utilising camera-captured printed images reduces issues with interobserver variability, although the issue of intratumorous heterogeneity remains as selecting which tumour area will be subjected to counting can be difficult to establish with consistency.27 Therefore, some pathologists resort to eyeball estimations, resulting in poor reproducibility and interobserver variability relating to the pathologists experience.28 Digital image analysis has been heralded as a means of deriving uniformity, but it is not currently widely employed as a result of a number of obstacles, including technical issues (eg, overcounting unwanted cells and underestimating negative cells) as well as its current lack of worldwide availability.

This meta-analysis provides tentative evidence demonstrating that high Ki-67 indices are associated with a 40% greater risk of recurrence among patients diagnosed with pulmonary NENs. This risk appears to be further exaggerated when considering OS, where patients with a high Ki-67 have double the risk of death in comparison with patients with a lower Ki-67 LI. The strength of the association between Ki-67 LI and prognosis was only evaluated in studies that calculated HRs using univariate analyses. As a result, no attempt has been made to account for confounding factors (such as stage, grade and mitotic index).

One of the major pitfalls of including Ki-67 in the classification of pulmonary NENs has in establishing the most appropriate thresholds or cut-offs that should be utilised when grading tumours. In the main, Ki-67 has not been used as a linear biomarker within the whole pulmonary NEN cohort, instead focusing on its utility within each categorical histological subtype. While categorising NENs by grade is helpful in establishing management plans, it is likely that proliferative markers (such as Ki-67 and mitotic index) are continuous rather than categorical variables. Therefore, there may not be a single or absolute optimal cut-off value to categorise tumours into distinct entities and a pragmatic approach is likely to be needed. In order to facilitate clinical clarity, it would be preferable to use the same thresholds as are utilised in GEP-NETs and any future studies should attempt to clarify this further. However, it is unclear whether attempting to implement a similar grading system in pulmonary NENs as GEP NENs does a disservice to the fundamental biological diversity between the two different tumour sites.29 Examples of this diversity include the variability of genetic alterations seen as well as the differing rates of associated syndromes and hormone expression.30–35

Unfortunately only two studies involving SCLC and high-grade neuroendocrine carcinomas of the lung were available. It is important to clarify that Ki-67 is not likely to be useful in subtyping these tumours prognostically. A number of biomarkers have been identified, which may have greater utility in these patients. Nevertheless, further research into Ki-67 is required in these tumour groups with such little evidence, especially in light of the fact that, in GEP-NENs, there is good evidence to suggest that Ki-67 is contributory with a cut-off of 55%.36

As with all studies, this meta-analysis is also subjected to inherent limitations. None of the studies included in the meta-analyses was prospective in design; retrospective analyses are prone to error through issues with selection bias and reporting. Second, studies with a variety of endpoints (eg, RFS analyses included studies where the endpoint was DFS and time to progression analyses, etc), diverse cohort sizes, differences in the dilution of the primary antibody as well as variable Ki-67 cut-offs have all been amalgamated. While some degree of heterogeneity is always to be expected, it diminishes the validity of the combined data set and subsequent results. This is reflected in the I2 statistics noted across both meta-analyses.

This study also preferentially utilised univariate analyses. While multivariate analyses can be significantly distorted by differing in their approach to modelling or prognostic factors, univariate analyses fail to account for confounding variables. Furthermore, given the small number of studies identified as suitable for inclusion in this meta-analysis, it is clear that future international multicentre efforts are needed to develop studies which are prospective with large cohorts to clarify whether Ki-67 labelling index is truly a prognostic biomarker in the setting of bronchopulmonary NENs.

Conclusions

Although it is difficult to draw definitive conclusions, this meta-analysis of over 1250 patients with pulmonary NENs indicates that a high Ki-67 LI is associated with an adverse prognosis. While these findings are subjected to a number of limitations, they provide a valuable insight into a rare tumour and should be considered when producing new guidelines regarding the use of Ki-67 in pulmonary NENs.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: SN contributed to the study question, protocol design, screening, data collection, data analysis, dissemination of results including preparation of the manuscript. CH contributed to the screening and data collection. LT, NWP, BG and EJ contributed to protocol design. LP assisted with the statistical analysis. CHO, JC and GP were responsible for the study question; all authors have been involved in the preparation of the manuscript. SN and GP act as guarantors.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

This study does not involve human participants.

References

- 1.Travis WD, Burke AP, Marx A, et al. WHO classification of tumours of the lung, pleura, thymus and heart. Int Agency Res Cancer 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Asamura H, Kameya T, Matsuno Y, et al. Neuroendocrine neoplasms of the lung: a prognostic spectrum. J Clin Oncol 2006;24:70–6. 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.1202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ducrocq X, Thomas P, Massard G, et al. Operative risk and prognostic factors of typical bronchial carcinoid tumors. Ann Thorac Surg 1998;65:1410–4. 10.1016/S0003-4975(98)00083-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Soga J, Yakuwa Y. Bronchopulmonary carcinoids: an analysis of 1,875 reported cases with special reference to a comparison between typical carcinoids and atypical varieties. Ann Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1999;5:211–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gerdes J, Schwab U, Lemke H, et al. Production of a mouse monoclonal antibody reactive with a human nuclear antigen associated with cell proliferation. Int J Cancer 1983;31:13–20. 10.1002/ijc.2910310104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Menon SS, Guruvayoorappan C, Sakthivel KM, et al. Ki-67 protein as a tumour proliferation marker. Clin Chim Acta 2019;491:39–45. 10.1016/j.cca.2019.01.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cuylen S, Blaukopf C, Politi AZ, et al. Ki-67 acts as a biological surfactant to disperse mitotic chromosomes. Nature 2016;535:308–12. 10.1038/nature18610 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de Azambuja E, Cardoso F, de Castro G, et al. Ki-67 as prognostic marker in early breast cancer: a meta-analysis of published studies involving 12,155 patients. Br J Cancer 2007;96:1504–13. 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603756 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khor L-Y, Bae K, Paulus R, et al. MDM2 and Ki-67 predict for distant metastasis and mortality in men treated with radiotherapy and androgen deprivation for prostate cancer: RTOG 92-02. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:3177–84. 10.1200/JCO.2008.19.8267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jann H, Roll S, Couvelard A, et al. Neuroendocrine tumors of midgut and hindgut origin: tumor-node-metastasis classification determines clinical outcome. Cancer 2011;117:3332–41. 10.1002/cncr.25855 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Klöppel G, La Rosa S. Ki67 labeling index: assessment and prognostic role in gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms. Virchows Arch 2018;472:341–9. 10.1007/s00428-017-2258-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Richards-Taylor S, Ewings SM, Jaynes E, et al. The assessment of Ki-67 as a prognostic marker in neuroendocrine tumours: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Pathol 2016;69:612–8. 10.1136/jclinpath-2015-203340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pelosi G, Bianchi F, Hofman P, et al. Recent advances in the molecular landscape of lung neuroendocrine tumors. Expert Rev Mol Diagn 2019;19:281–97. 10.1080/14737159.2019.1595593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Klimstra D, Kloppel G, La Rosa Salas B. Classification of neuroendocrine neoplasms of the digestive system. In: WHO classification of tumours. Digestive system tumours. 5th edn, 2019: 16–21. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marchevsky AM, Hendifar A, Walts AE. The use of Ki-67 labeling index to grade pulmonary well-differentiated neuroendocrine neoplasms: current best evidence. Mod Pathol 2018;31:1523–31. 10.1038/s41379-018-0076-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Naheed S, Holden C, Tanno L. The utility of Ki-67 as a prognostic biomarker in pulmonary neuroendocrine tumours. BMJ Open 2019;9:e031531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stang A. Critical evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Eur J Epidemiol 2010;25:603–5. 10.1007/s10654-010-9491-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cusumano G, Fournel L, Strano S, et al. Surgical resection for pulmonary carcinoid: long-term results of multicentric Study-The importance of pathological N status, more than we thought. Lung 2017;195:789–98. 10.1007/s00408-017-0056-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vesterinen T, Mononen S, Salmenkivi K, et al. Clinicopathological indicators of survival among patients with pulmonary carcinoid tumor. Acta Oncol 2018;57:1109–16. 10.1080/0284186X.2018.1441543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marchiò C, Gatti G, Massa F, et al. Distinctive pathological and clinical features of lung carcinoids with high proliferation index. Virchows Arch 2017;471:713–20. 10.1007/s00428-017-2177-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Filosso PL, Oliaro A, Ruffini E, et al. Outcome and prognostic factors in bronchial carcinoids: a single-center experience. J Thorac Oncol 2013;8:1282–8. 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31829f097a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Clay V, Papaxoinis G, Sanderson B, et al. Evaluation of diagnostic and prognostic significance of Ki-67 index in pulmonary carcinoid tumours. Clin Transl Oncol 2017;19:579–86. 10.1007/s12094-016-1568-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rindi G, Klersy C, Inzani F. A three tier grading system based on Ki-67 index, mitotic count and necrosis with cut-offs specifically generated for lung neuroendocrine tumors is prognostically effective and accurate. Neuroendocrinology 2014;99:251. [Google Scholar]

- 24.de M Rêgo JF, de Medeiros RSS, Braghiroli MI, et al. Expression of ERCC1, Bcl-2, LIN28A, and Ki-67 as biomarkers of response to first-line platinum-based chemotherapy in patients with high-grade extrapulmonary neuroendocrine carcinomas or small cell lung cancer. Ecancermedicalscience 2017;11:767. 10.3332/ecancer.2017.767 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fabbri A, Cossa M, Sonzogni A, et al. Ki-67 labeling index of neuroendocrine tumors of the lung has a high level of correspondence between biopsy samples and surgical specimens when strict counting guidelines are applied. Virchows Arch 2017;470:153–64. 10.1007/s00428-016-2062-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pelosi G, Rindi G, Travis WD, et al. Ki-67 antigen in lung neuroendocrine tumors: unraveling a role in clinical practice. J Thorac Oncol 2014;9:273–84. 10.1097/JTO.0000000000000092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reid MD, Bagci P, Ohike N, et al. Calculation of the Ki67 index in pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors: a comparative analysis of four counting methodologies. Mod Pathol 2015;28:686–94. 10.1038/modpathol.2014.156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Klimstra DS, Modlin IR, Adsay NV, et al. Pathology reporting of neuroendocrine tumors: application of the Delphic consensus process to the development of a minimum pathology data set. Am J Surg Pathol 2010;34:300–13. 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181ce1447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kasajima A, Klöppel G. Neuroendocrine neoplasms of lung, pancreas and gut: a morphology-based comparison. Endocr Relat Cancer 2020;27:R417–32. 10.1530/ERC-20-0122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jiao Y, Shi C, Edil BH, et al. DAXX/ATRX, MEN1, and mTOR pathway genes are frequently altered in pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Science 2011;331:1199–203. 10.1126/science.1200609 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Simbolo M, Barbi S, Fassan M, et al. Gene expression profiling of lung atypical carcinoids and large cell neuroendocrine carcinomas identifies three transcriptomic subtypes with specific genomic alterations. J Thorac Oncol 2019;14:1651–61. 10.1016/j.jtho.2019.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Swarts DRA, Scarpa A, Corbo V, et al. MEN1 gene mutation and reduced expression are associated with poor prognosis in pulmonary carcinoids. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2014;99:E374–8. 10.1210/jc.2013-2782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Alcala N, Leblay N, Gabriel AAG, et al. Integrative and comparative genomic analyses identify clinically relevant pulmonary carcinoid groups and unveil the supra-carcinoids. Nat Commun 2019;10:3407. 10.1038/s41467-019-11276-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gustafsson BI, Kidd M, Chan A, et al. Bronchopulmonary neuroendocrine tumors. Cancer 2008;113:5–21. 10.1002/cncr.23542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pape U-F, Jann H, Müller-Nordhorn J, et al. Prognostic relevance of a novel TNM classification system for upper gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Cancer 2008;113:256–65. 10.1002/cncr.23549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sorbye H, Welin S, Langer SW, et al. Predictive and prognostic factors for treatment and survival in 305 patients with advanced gastrointestinal neuroendocrine carcinoma (WHO G3): the Nordic NEC study. Ann Oncol 2013;24:152–60. 10.1093/annonc/mds276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2020-041961supp001.pdf (54.5KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information.