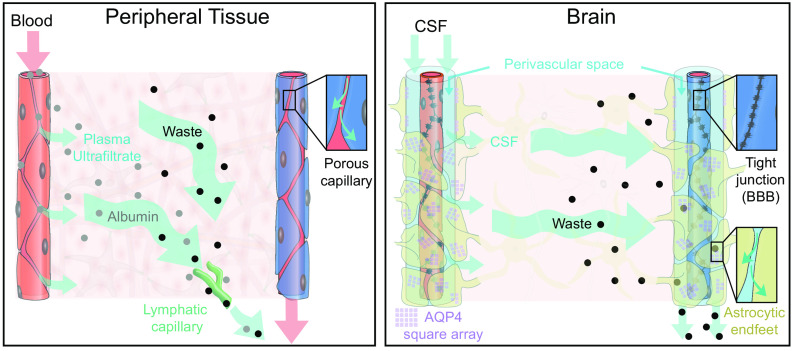

FIGURE 1.

Comparison of fluid and solute flow in peripheral tissues and brain. The source of fluid in peripheral tissue is the porous capillaries, which are permeable to plasma and globular proteins like albumin (gray circles). In addition, endothelial cells express aquaporin-1 (AQP1) water channels. A hydrostatic pressure gradient drives an ultrafiltrate of plasma and globular proteins into the tissue at the arterial end of the capillary bed, while most of the fluid and extracellular proteins, including waste products (black circles) are transported out of peripheral tissues by lymphatic vessels. In the brain, the blood brain barrier (BBB) formed by capillary endothelial cell tight junctions largely prevents influx of vascular fluid and proteins. Instead, the brain produces its own fluid, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). CSF is transported into deep parts of the brain along the periarterial spaces. The unique perivascular spaces of the central nervous system are annular CSF-filled tunnels with low resistance to fluid flow, which are created by a convoluted surface of loosely interconnected astrocytic endfeet plastering the entire cerebral vasculature, including arteries, capillaries and veins. The arterial wall pulsatility drives CSF influx into the neuropil, facilitated by the aquaporin-4 (AQP4) water channels on the astrocytic endfeet. AQP4 channels form square arrays that occupy up to 60% of the surface of astrocytic endfeet facing the perivascular space (John Rash, personal communication). In contrast, brain endothelial cells express few or no water channels. The extracellular fluid and protein waste produced during neural activity are transported to and leave the brain along perivenous spaces for ultimate export by meningeal lymphatic vessels and along cranial and spinal nerve sheaths.