Abstract

In an attempt to move the field of public health from documenting health disparities to acting to rectify them, in 2001, the American Public Health Association (APHA) recognized racism as a fundamental cause of racial health disparities. Both APHA and the Council on Education for Public Health have moved to incorporate new competencies in health equity for public health professionals. As schools and programs of public health work to establish curricular offerings in race and racism, a need exists to identify approaches currently in use that can be replicated, adapted, and scaled. This systematic review sought to identify pedagogical methods and curricula that exist to support the training of US public health students in understanding racism as a structural determinant of health. We found 11 examples from peer-reviewed literature of curricula, lessons, and competencies that have been developed by public health faculty and departments since 2006. The articles discussed a range of approaches to teaching about structural racism in public health, suggesting that little consensus may exist on how to best teach this material. Furthermore, we found little rigorous evaluation of these teaching methods and curricula. The results of this review suggest future research is needed on public health pedagogy on structural racism.

Keywords: racial justice, antiracism, structural racism, pedagogy, health equity

With the resurgence of white nationalism in the past 2 decades, 1 -3 renewed calls have been made to address racism and white supremacy in US institutions. Many fields, including public health, are examining their past to understand how historical steeping in racist thought and behavior may influence present-day positionality and outcomes. 4 Although these efforts may be more broad based and publicly visible now than previously, such critical engagement builds on decades of scholarship and advocacy in public health. 5 This previous work led to the development of a rich body of research and practice that documents racial disparities, characterizes the ways in which racism functions as a structural driver of social determinants of health, and promotes equity and intergenerational healing from racist trauma. 6 -11 Despite the growth of the related fields of health equity and antiracist public health research and praxis in recent decades, relatively little is written about teaching these concepts in public health education.

US public health education is indelibly shaped by the legacy of Jim Crow. At the turn of the 20th century, the field was in its infancy and largely considered a subspecialty of medicine; public health was also sometimes referred to as preventive medicine or hygiene and sanitation. 12 The 1910 publication of Medical Education in the United States and Canada by Abraham Flexner, better known as the Flexner Report, 13 and the 1915 Welch–Rose Report 14 were instrumental in shaping the early development of public health pedagogy. The Flexner Report, often credited with establishing criteria for schools of medicine, reorganized medical education around laboratory and clinical science. 13 It also shuttered 5 of the 7 schools of medicine that admitted Black students, arguing Black students needed “good schools rather than many schools—schools to which the more promising of the race can be sent to receive a substantial education in which hygiene rather than surgery, for example, is strongly accentuated.” 13 The Flexner Report stated that schools serving Black students were “at this moment in no position to make any contribution of value” but provided no further evidence to support the claim. 13 Remaining schools were then able to broaden their curricular offerings, including through programs of study in public health.

The 1915 Welch–Rose Report, developed by a Flexner-led commission, laid the foundation for institutes of public health as professional training schools. The report stated that schools of public health should “be closely affiliated with a university . . . medical school” 14 and underscored a biomedical disease model of public health centered on hygiene. 15 Institutions serving White students were closed to Black students, severely curtailing access to education and credentialing in medicine and public health. 16 Throughout the 20th century, institutions of higher education that served White students primarily offered public health programs of study, at a time when the color line was still well-established and strongly enforced. In fact, the Council on Education for Public Health (CEPH) did not accredit a master of public health degree program at a Historically Black College or University until 1999 17 ; therefore, no accredited public health courses of study were available to Black students until institutions serving White students began to desegregate under legal orders in the 1950s. 18 Details on the history of desegregation in public health institutions are available elsewhere. 5,19,20 These historical barriers to accessing public health education have lasting importance, contributing to, for example, the contemporary dearth of senior Black academicians.

The 1980s and 1990s witnessed the rise of a cadre of Black public health scientists and increasing focus on “minority health.” 5 Although Black scholars called attention to ways public health failed to serve Black and other communities of color, the pedagogy of the predominantly White academy largely reinforced structural racism by presenting health disparities as the result of cultural deficits and poor personal health choices rather than systems of oppression. 21 To move the field from documenting disparities to rectifying them, in 2001 the American Public Health Association (APHA) recognized racism as a fundamental cause of racial health disparities. 22 Both APHA and CEPH have moved to incorporate new competencies in health equity, 23,24 underscoring the need for curricula that name racism and equip emerging professionals to actively dismantle racist systems. These changes are largely in response to ongoing leadership and advocacy by Black scholar–activists who have championed efforts to teach and address the role of internalized, interpersonal, and structural racism in the etiology of health disparities. 25

As schools and programs of public health expand curricular offerings on racism, identifying approaches that can be replicated, adapted, and scaled is necessary. Although much has been written about teaching cultural competency and implicit bias, 26,27 less has been published on teaching about racism as a structural determinant of health (tracing its history, how it was encoded into health-related policy, and how it produces disparate health outcomes) or methods to address structural racism to achieve health equity. Therefore, the objective of this systematic review was to synthesize peer-reviewed literature describing programs, curricula, and pedagogical methods designed to train students attending schools and programs of public health in the United States in structural racism and the application of racial equity principles to public health practice and scholarship.

Methods

Search Strategy

We developed a search protocol following Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines to identify literature catalogued in 6 electronic databases (PubMed, ProQUEST Health Management, EBSCOHost ERIC, EBSCOHost MasterFILE Premier, Scopus, and Web of Science) published from inception through February 15, 2019. The search was subsequently updated through April 3, 2020. We collaborated with a health sciences librarian to develop a search strategy for each database with search terms related to racial equity, public health, and education (Box).

Box. Search terms used in a systematic review to identify US undergraduate and graduate public health training programs, curricula, and pedagogical methods related to structural racism and racial equity in 6 electronic databases from their inception through April 3, 2020.

| (“Racial equity” OR “health equity” OR “racial justice” OR “cultural humility” OR “critical race” OR “structural racism” OR “structural competence” OR “institutional racism” OR “institutionalized racism” OR “reproductive justice” OR “reproductive oppression” OR “reproductive freedom” OR “social justice” OR “cultural competence” OR “cultural humility” OR “cultural competency” OR “cultural sensitivity” OR “popular education”) |

| AND |

| (“public health” OR population OR public OR community) |

| AND |

| (education OR educational OR training OR trainings OR workshop OR workshops OR workshopping OR curriculum OR curricula OR curricular OR pedagogy OR pedagogical OR pedagogies OR institute OR institutes) |

Eligibility Criteria

We included articles in peer-reviewed journals published in English that discuss teaching, training, and/or capacitating public health students in racial equity. We defined racial equity capacitation as a curriculum or training on (1) the historical antecedents of racialized health disparities/inequities, (2) institutional and/or structural racism, (3) the intersection between policy and racialized health disparities (both historic and contemporary), or (4) applied antiracism. Articles included quantitative, qualitative, and mixed-methods studies; commentaries; and case reports (which may not have been peer reviewed despite being published in a peer-reviewed publication). We included articles that described lessons, curricula, or programs for students enrolled in a school or program of public health in the United States, regardless of level (undergraduate, master, or doctoral), format (residential or online), or accreditation status. The primary outcome measures for this review were increased awareness of racial equity principles, improved understanding of how structural and institutional racism undermine population health, and enhanced ability to apply racial equity approaches to conducting public health work and scholarship. We included studies if these outcomes were described in the curriculum/training learning objectives and/or evaluation outcomes, although evaluation of the curriculum/training was not necessary for inclusion.

We excluded studies that focused solely on in-service training or continuing education and training designed exclusively for direct service providers (eg, social workers, health practitioners in clinical roles). Because the focus of this review was public health professional training programs in the United States, we excluded studies that discussed public health training for high school students or students in other grades, were conducted outside the United States, were designed for students in other countries, and/or exclusively focused on geographic contexts other than the United States. Finally, reflecting our focus on structural racism, we excluded studies focused solely on instructional programs to reduce or eliminate interpersonal racism and/or bias.

Screening Protocol

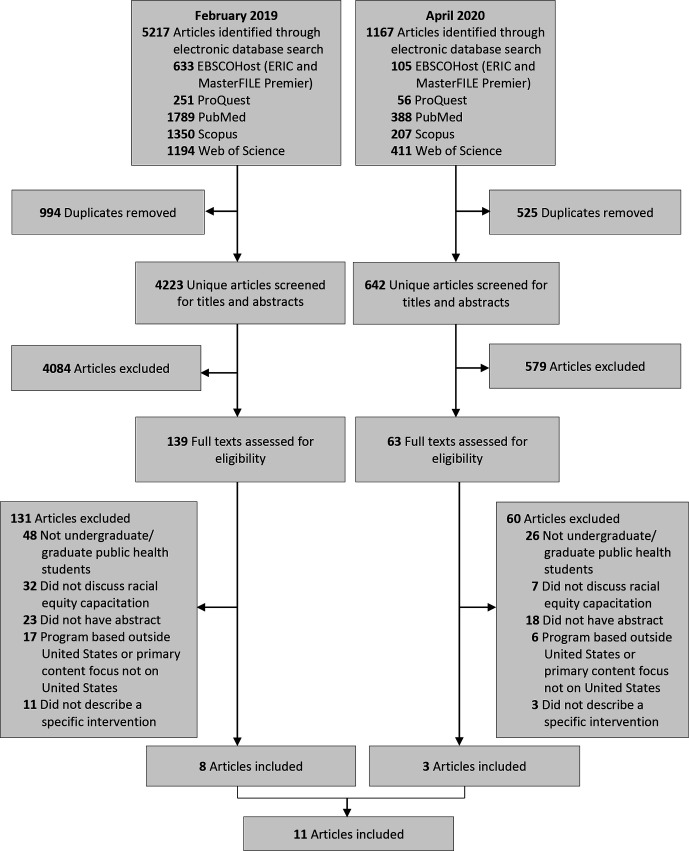

Our searches returned 6384 results, including 4865 unique articles (Figure). Three reviewers (C.E.C., M.W.T., C.R.W.) screened each title and abstract for potential inclusion and identified 202 articles for full-text review. In pairs, the same 3 reviewers independently screened each article in full-text review. The team of 3 reviewers held conferences to resolve discrepancies in decisions to include or exclude articles as well as discrepancies in the reason for exclusion. Eleven articles met eligibility criteria. A hand search of reference lists of included articles did not identify any additional articles to include.

Figure.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) diagram of articles identified as describing approaches for training public health students in structural racism and racial equity. Searches conducted in February 2019 and April 2020. Exclusion criteria were not mutually exclusive; only the primary reason for exclusion is reflected in the PRISMA diagram.

Data Extraction and Analysis

We extracted data from the 11 articles meeting eligibility criteria. We developed a standardized data extraction form through REDCap, an open-source online platform that facilitates data collection and management. We conducted a thematic analysis on extracted data to identify commonalities in key topic areas and pedagogical approaches across the instructional programs described in the identified articles.

Results

Topic and Content

The 11 articles framed key instructional topic areas in terms of health disparities or inequities (n = 3), 28 -30 structural issues (n = 3), 28,31,32 social determinants of health (n = 3), 32 -34 racism or antiracism (n = 2), 33,35 social justice (n = 1), 36 health (n = 1), 37 and pedagogy of collegiality (ie, application of feminist and critical theories in classroom activities and assignments to promote inclusion of diverse learning styles, open communication between students and instructors, community building, and multicultural education) (n = 1), 38 and used widely varying program content to capacitate students in racial equity (Table 1). For example, programs incorporated racial equity capacitation by using interactive lessons to teach about power, oppression, and privilege 28,38 or through using the television show The Wire to study the interplay of political, cultural, structural, and individual factors that perpetuate health disparities. 30,31 Other faculty members lectured on Dr Camara Jones’ Three Levels of Racism framework. 39 Moving beyond the classroom, some curricula guided students through a museum tour of exhibits on Black Wall Street and the Tulsa Race Massacre 33 or incorporated arts rooted in African communities to teach about the role of historical relations among political authorities, individuals, and collectives in producing health inequities without reifying inequities. 29 Other programs examined the effects of federal and state policies on health disparities 32,36 ; explored the social, political, and economic upstream factors, such as trade policy, that contextualize individual behaviors 34 ; and analyzed the effect of colonial processes on the health outcomes of Indigenous Peoples. 37 One program developed a schoolwide antiracism competency with courses that build students’ skills in antiracist analysis. 35

Table 1.

Components of US undergraduate and graduate public health training programs, curricula, and pedagogical methods for teaching about structural racism and racial equity in studies published before April 2020: results of a systematic review

| Author | Program description | Intervention setting, duration, materials, and evaluation | Audience a | Instructor(s) b | Pedagogical approach c |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Browne et al, 2013 28 |

Program summary: Authors analyzed online responses to local news stories about health disparities and reflected on how that information could be used to prepare students for work on eliminating health disparities. Responses to news stories showed the public’s belief that disparities were “leftist liberal” political agendas or the result of individual factors of Black people. Authors suggest framing health disparities in terms of “agent” (ie, group to whom society has given greater power/privilege) and “target” (ie, group for whom society limits power) groups to encourage students to examine oppression at a structural rather than individual level, using these real-world examples. Key topic areas: Health disparities, structural issues, racialized contexts |

Setting: Classroom Duration: Not stated Materials: Action planning worksheet, discussion questions Evaluated: No |

Graduate students and undergraduate students | Faculty | Group discussion |

| Buttress et al, 2013 31 |

Program summary: Seminar series that used The Wire to examine the context of urban health disparities: the interplay among political, cultural, structural, and individual factors that perpetuate disparities. For example, one seminar used The Wire to frame a discussion on the relationships among deindustrialization, policing, drug policy, and gun violence among African American young people. Key topic areas: Structural issues that affect urban health |

Setting: Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health seminar series Duration: 9 seminars Materials: The Wire (HBO series) Evaluated: No |

This seminar was hosted by the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health and open to the community, including students. It was not clear if the seminar was targeted specifically for undergraduate or graduate public health students. | Faculty, community members, organizations, other | Didactic lecture/seminar talk, group discussion |

| Chávez et al, 2006 38 |

Program summary: A semester-long course, “Public Health Through a Lens of Community Organizing,” used pedagogy of collegiality

d

to shift students’ thinking from a biomedical understanding of illness and disease to an explicit use of language about social justice, cultural competence, and human rights. Instructors used techniques such as journaling, ethnographic study, and community circle to teach about such topics as social justice, human rights, ethics of community-based research, and power, oppression, and privilege. Key topic areas: Pedagogy of collegiality centered on 4 essential features: (1) principles of community organizing, (2) building community and valuing diversity, (3) engaging the senses, and (4) writing across the curriculum. |

Setting: Introductory public health course for students in master of public health program Duration: 15-wk semester Materials: Music, classroom decorations (eg, textiles from various cultures), paper Evaluated: Yes |

Graduate students | Faculty, graduate teaching assistants | Didactic lecture/seminar talk, group discussion, group project, individual project, experiential |

| Dennis et al, 2019 33 |

Program summary: Program integrated a didactic lesson on the Three Levels of Racism,

38

workshops on privilege and implicit bias, and a museum tour of an exhibit on Black Wall Street and the Tulsa Race Massacre. Key topic areas: Understanding racism as an SDH by examining structural, personally mediated, and internalized racism |

Setting: Lecture and workshop series for a community medicine residency program and community health leadership program Duration: 4-5 h during an 11-mo period Materials: YouTube videos, paper, community report cards, museum exhibit Evaluated: Yes |

Graduate students | Faculty, community members, or organizations | Didactic lecture/seminar talk, group discussion, experiential |

| Garcia et al, 2019 32 |

Program summary: Facilitators used interactive didactic PowerPoint presentations and videos to discuss SDH and structural determinants of health (eg, the effect of federal policies on health outcomes of American Indian/Alaska Native people). They then engaged participants in a storytelling activity to teach about access to health care among American Indian/Alaska Native people. Key topic areas: SDH and structural determinants of health among urban American Indian/Alaska Native people |

Setting: Workshop for medical students, residents, physicians, and other health care professionals or trainees, including graduate students in public health Duration: 90 min Materials: Facilitator’s guide, PowerPoint presentation, land acknowledgment resources, videos (Honor Native Land, The Art of Indigenous Resistance), storytelling cards, evaluation forms Evaluated: Yes |

Graduate students | Faculty, other (racial equity consultants from outside the host institution) | Didactic lecture/seminar talk, group discussion, experiential |

| Hagopian et al, 2018 35 |

Program summary: A schoolwide antiracism competency that was adopted to guide antiracism training across programs and departments. Courses designed to meet this competency developed skills in antiracist analysis. Key topic area: Antiracism competency to “recognize the means by which social inequities and racism, generated by power and privilege, undermine health.” |

Setting: Schoolwide antiracism competency Duration: Ongoing Materials: Toolkit with case examples to guide course instructors to improve inclusive teaching practices Evaluated: Yes |

Graduate students and undergraduate students | Faculty, graduate teaching assistants, other (racial equity consultants from outside the host institution) | Guiding competency |

| McGrath, 2019 29 |

Program summary: Described a pedagogical approach for teaching about social processes that produce health inequities among African communities (on and off the continent) in a way that does not reify the inequities themselves—in particular, by using arts rooted in these communities. Suggests studying present and past forms of public health by examining historical relations among political authorities, individuals, and collectives. Key topic areas: Social processes that produce health inequities among African communities |

Setting: Classroom Duration: Not stated Materials: Unequal Causes documentary, artistic materials that represent African lives (eg, Everyday Africa Instagram account), materials by and about African people Evaluated: No |

Graduate students and undergraduate students | Faculty | Didactic lecture/seminar talk, group discussion |

| Mogford et al, 2011 34 |

Program summary: A critical health literacy workshop or course that can be adapted to meet the needs of the audience. The curriculum is guided by a 4-part framework: (1) Knowledge of SDH and health as a human right. This component includes a “causes of the causes” activity, pushing students to analyze individual behaviors in the context of social, political, and economic upstream factors such as international trade agreements and global markets. (2) Students as social change agents. (3) Advocacy tools and strategies. (4) Development and implementation of actions intended to increase equity by addressing SDH. Key topic area: Applying the critical health literacy framework to address SDH |

Setting: Course or workshop in a classroom, community health center, or other community settings Duration: Ranged from 2-h workshop to 12-wk course Materials: Universal Declaration of Human Rights; Just Health Actions advocacy continuum; Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Treats analysis tool; Objective, Reflective, Interpretive, Decisional facilitation tool Evaluated: Yes |

Graduate students and undergraduate students | Community members or organizations | Didactic lecture/seminar talk, group discussion, group project, individual project |

| Rosales et al, 2012 36 |

Program summary: Described strategies to incorporate social justice into the master of public health curriculum, including discussions in existing courses, lunchtime discussions and trainings on research and interventions, service learning with community coalitions to learn about the short-term and long-term effects of social injustice, an annual social justice symposium, and a course with service-learning opportunities that includes working with underserved communities to raise awareness of how federal and state policies affect communities. Key topic areas: Social justice and health |

Setting: Public health courses Duration: Not stated Materials: Not stated Evaluated: No |

Graduate students and undergraduate students | Faculty | Didactic lecture/seminar talk, group discussion, experiential |

| Taualii et al, 2013 37 |

Program summary: Six competencies to prepare students to assist in addressing the health and wellness needs of Indigenous People: (1) Describe Indigenous Peoples’ health in a historical context and analyze the effect of colonial processes on health outcomes. (2) Analyze key comparative health indicators and SDH for Indigenous Peoples. (3) Critically evaluate Indigenous public health policy and programs. (4) Apply the principles of economic evaluation to Indigenous programs, with a particular focus on the allocation of resources relative to need. (5) Demonstrate a reflexive public health practice for the health contexts of Indigenous Peoples. (6) Demonstrate a disease prevention strategy that values and incorporates the traditional knowledge of Indigenous Peoples. Key topic area: Native Hawaiian and Indigenous health |

Setting: Competencies to support a Native Hawaiian and Indigenous Health concentration Duration: Master of public health program Materials: Not stated Evaluated: No |

Graduate students | Faculty | Didactic lecture/seminar talk, experiential, guiding competency |

| Tettey, 2018 30 |

Program summary: Students watched season 4 of The Wire and used the socioecological model to analyze a character’s life and the contextual factors that influence that character. The Wire helps students understand both the “what” of health disparities and the “how” and “why” by presenting the intersectionality of concentrated poverty, a failed education system, corrupt government, mass incarceration, and the war on drugs, among other factors. Key topic area: Health disparities |

Setting: Undergraduate public health course Duration: Semester Materials: Season 4 of The Wire (HBO series) Evaluated: Yes |

Undergraduate students | Faculty | Group discussion, individual project |

Abbreviation: SDH, social determinants of health.

aCategories were graduate students and undergraduate students.

bCategories were faculty, graduate teaching assistants, community members or organizations, and other.

cCategories were didactic lecture/seminar talk, group discussion, group project, individual project, experiential, and guiding competency (ie, competency adopted by a school or program of public health specifying knowledge and/or skills that all students should learn).

dApplication of feminist and critical theories in classroom activities and assignments to promote inclusion of diverse learning styles, open communication between students and instructors, community building, and multicultural education.

Instructional Program Format

Instructional programs included in-person classes (n = 8) 28 -30,34 -38 and workshops or seminars (n = 4). 31 -34 Instructional program durations varied, from 90-minute workshops 32 to semester-long courses. 30,38 One instructional program was designed only for undergraduate students, 30 5 were designed only for graduate students, 31 -33,37,38 and 5 were designed for both undergraduate and graduate students. 28,29,34 -36 The instructors for half the instructional programs were faculty members only (n = 5), 28 -30,36,37 whereas others included faculty members 31 -33,35,38 and a combination of graduate teaching assistants, 35,38 community members, 31,33 or other types of instructors (eg, racial equity consultants from outside the host institutions). 31,35 One instructional program was led solely by a nonprofit organization that taught critical health literacy working toward health equity. 34 Pedagogical approaches included didactic lecture/seminar talk (n = 8), 29,31 -34,36 -38 group discussion (n = 9), 28 -34,36,38 group projects (n = 2), 34,38 individual projects (n = 3), 30,34,38 worksheets (n = 1), 28 experiential learning (n = 5), 32,33,36 -38 and guiding competencies (n = 2). 35,37 All but 1 article 35 used a combination of pedagogical approaches. Materials and resources ranged widely and included in-person presentations, 32 music, 38 classroom decorations and other artistic materials, 29,38 YouTube videos, 33 a local museum, 33 documentaries, 29 television shows, 30,31 and toolkits. 35

Evaluation

Six of the 11 programs included some form of evaluation (Table 2). 30,32 -35,38 Evaluation designs included qualitative and quantitative feedback on lessons, courses, or course offerings (n = 4) 30,32,33,38 ; pretests–posttests of knowledge (n = 2) 32,34 ; and audits of course materials (n = 1). 35 Key evaluation indicators included feedback on sessions 33,38 and knowledge of core concepts. 32,34 Key indicators were not stated in 2 articles. 30,35 Outcomes of the evaluations showed positive qualitative and quantitative feedback on sessions (eg, enjoyment of session) and self-reported increases in knowledge. 30,32,33,38 Two articles did not discuss the results of the evaluations. 34,35

Table 2.

Evaluation design and outcomes of US undergraduate and graduate public health training programs, curricula, and pedagogical methods for teaching about structural racism and racial equity in studies published before April 2020: results of a systematic review

| Authors | Evaluation design | Key indicators | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chávez et al, 2006 38 | Course evaluations | Not stated; presented selected quotes | Quotes presented were positive and showed that students found the pedagogy engaging. |

| Dennis et al, 2019 33 | Anonymous quantitative assessment of didactic sessions; nonanonymous qualitative feedback sent from fellows via email, analyzed by using inductive methods | Quality of didactic session (on 5-point Likert-type scale, with 1 = did not meet expectations and 5 = exceeded expectations) | All sessions had a mean score >4 on a 5-point scale, indicating that didactic sessions met expectations. Common themes that emerged from qualitative feedback were appreciation; a positive experience; awareness/education; mixed concerns (getting too much of this content, need more time to discuss, need more definitions); topic is sensitive; training will lead to advocacy and education; deepened understanding of bias and privileges (critical consciousness); challenged assumptions of self, colleagues, patients, and clients; and increased self-awareness/critical self-awareness. |

| Garcia et al, 2019 32 | Preworkshop and postworkshop questionnaire (~5 min) designed to assess participants’ knowledge of content about American Indian/Alaska Native people, demographic information about participants, and feedback about the effectiveness of the workshop | Change in knowledge about 5 content areas as demonstrated by an increase in the correct answer being chosen on multiple-choice questions | Paired-sample t test demonstrated a significant increase in the mean number of correct responses. All participants agreed or strongly agreed that the workshop met the identified learning objectives. |

| Hagopian et al, 2018 35 | A doctoral student reviewed all course materials for diversity-related topics, conducted interviews of faculty, held focus groups of students in the core courses, and presented findings at faculty meetings. | Not stated | Not stated |

| Mogford et al, 2011 34 | Process evaluation used student reflections and journal responses to inform curriculum adaptations. Pretest and posttest survey administered to measure outcomes. | Knowledge of social determinants of health (SDH), health inequities, and health as a human right; attitudes about SDH, human rights, and activism; self-efficacy and future intentions to act on SDH | Authors stated that preliminary results were positive, but those results have not yet been published. |

| Tettey, 2018 30 | End-of-course discussion and open-ended survey | Not stated | Students felt The Wire was an effective teaching tool that helped them make connections between SDH and health outcomes in the characters. |

Discussion

Since at least 2008, racism has been described as a structural determinant that shapes access and positionality with respect to social determinants of health. 40 Yet, the present systematic review found only 11 examples in the peer-reviewed literature that describe teaching about racism in this way, and only 7 of those examples presented any form of evaluation of teaching outcomes. The most rigorous evaluation design was a pretest–posttest in knowledge; most evaluations examined students’ emotional response to the material. Although key topic areas, settings, and pedagogical approaches for each instructional program differed, nearly all programs incorporated sociocultural content or materials to aid in students’ understanding of the historical contexts of racism in the United States.

The relative “thinness” of this literature means that as schools and programs of public health reexamine how they teach about racism and health equity, the available peer-reviewed literature provides little pedagogical guidance to inform such examination and consider changes. Schools and programs of public health must, per CEPH accreditation criteria, “explain the social, political and economic determinants of health and how they contribute to population health and health inequities,” 24 yet our findings suggest that little peer-reviewed evidence or consensus exists on how to effectively teach about racism. Individual scholars steeped in theory and research about racism as a structural determinant of health may be able to provide such education in a deep and thoughtful way (eg, threading together theory-based discussions of racism with scholarship on health disparities). However, other scholars may be ill-equipped to design course content that engages students to push past erroneous biological determinist beliefs about the origins of health disparities to understand the systems of inequity that underlie disparate outcomes. Without clear guidance on best practices and minimum standards, faculty members (who may themselves never have received such training) are left to exercise their best judgment in developing curricula on racism. Consequently, student learnings may vary.

Such concerns are not limited to education on racism as a structural determinant of health. The last decade has seen calls for more systematic and rigorous approaches to public health pedagogy, including through the development of competency-based models and learning communities on evidence-based education. 41 -43 Thus, our findings come alongside this broader movement for strengthening public health education, as increasing numbers of students pursue public health degrees. 44,45 Entering their degree programs on the heels of severe racial disparities in the COVID-19 pandemic and major national awakening around racism, incoming students will likely be aware that race is associated with health outcomes. In shaping that awareness into understanding, it will be incumbent on schools and programs of public health to provide evidence-based frameworks that contextualize race as an artificial construct with profound social meaning, not a biological fact. 5 Medicine and social work have begun to develop robust pedagogical literatures on racism as a structural determinant (often referred to as “structural competency”), which can help to inform public health thinking. 46 -50 This scholarship must be adapted to address population health but can serve as a useful starting point.

Limitations

This review had several limitations. First, we restricted our search to peer-reviewed journals, which are not the only avenue for sharing information on curricula and educational materials. Institutional websites such as those run by the Association of Schools and Programs of Public Health and the Association for Prevention Teaching and Research offer pedagogical resources to faculty. 43 Professional association meetings, such as the APHA annual meeting, also host sessions on education and pedagogy. 43 Our review omitted such gray literature sources because they are not systematically catalogued, but we acknowledge that they may contain a broader set of materials than represented here. In addition, faculty may learn about innovative pedagogical approaches from colleagues, through discussions, and by sharing syllabi. These informal networks are not documented in peer-reviewed journals yet may serve as an important source of best practices in teaching. Therefore, the dearth of literature in peer-reviewed journals found in our review should not be interpreted as a reflection on the state of teaching about racism as a structural determinant of health. Rather, it serves to show that such teaching is not well documented in the peer-reviewed literature.

A second limitation is related to the language used to describe work on racism in public health. Naming “racism” in public health research and practice was long taboo, and experts working to eliminate health disparities often took pains to find other language, perceived as more neutral, to describe their work. 5 In screening articles, we attempted to maintain a broad stance toward the kind of work that might be considered addressing racism as a structural determinant, and we did not require that the words racism or structural determinant be present to be included if the description of the focus of the program described aligned with definitions of racism and structural determinants of health. On one hand, this decision may have led to analytic imprecision in terms of what materials were included, contributing to the heterogeneity of the results. On the other hand, authors’ use of coded language to describe racism may have led us to exclude articles that otherwise would have merited inclusion.

Finally, this review focused strictly on programs, curricula, and pedagogical methods for students of public health so as to inform faculty in schools and programs of public health on effective strategies for teaching about structural racism and racial equity in the context of population health. This review did not capture information on pedagogical approaches used in other fields, including medicine, or the rich body of literature that is available to teach students about racism as a structural determinant of health. Indeed, textbooks, such as Racism: Science and Tools for the Public Health Professional 4 and Minority Populations and Health: An Introduction to Health Disparities in the United States, 51 and the growing bodies of literature on critical race theory and racism as a driver of health disparities are foundational resources that faculty may find useful as pedagogical tools.

Despite these limitations, this review—to our knowledge, the first systematic review on public health pedagogy of racism as a structural determinant of health—provides important information to the field. The breadth and interdisciplinarity of the included databases provided a wide survey of the field and explicitly included education-focused materials published outside traditional public health venues. The systematic search and screening procedure provided a rigorous methodological approach. Because this review was completed before the antiracist protests that followed the killing of George Floyd, it can provide a useful baseline for the state of peer-reviewed literature about antiracist public health education before renewed attention to racial injustice prompted schools and programs of public health to revisit health equity curricula.

Conclusion

Although a vibrant field exists of research and public health practice that understands the implications of racism as a structural determinant of health, literature on public health pedagogy on this topic is lagging. More research is needed to document how to educate public health students on the roots of the health issues they will address in their careers. Such education is critical so that the research, interventions, programs, and policies the public health workforce creates go beyond individual-level or superficial solutions, to change the systems that structure social determinants of health and subsequent health outcomes.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Jon Hussey, PhD, University of North Carolina Gillings School of Global Public Health, Department of Maternal and Child Health, for providing critical feedback in conceptualizing and developing this systematic review and Mary White, MS, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Health Sciences Library, for her help in developing the search strategy. We also thank reviewers for their thoughtful feedback.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Ms Chandler was supported by an award to the Carolina Consortium on Human Development from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (T32HD007376).

ORCID iD

Caroline E. Chandler, MPH  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4468-9626

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4468-9626

References

- 1. Swain CM. The New White Nationalism in America: Its Challenge to Integration. Cambridge University Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Jones SG. The rise of far-right extremism in the United States. Center for Strategic & International Studies. 2018. Accessed August 13, 2020. https://www.csis.org/analysis/rise-far-right-extremism-united-states

- 3. Giroux HA. White nationalism, armed culture and state violence in the age of Donald Trump. Philos Soc Crit. 2017;43(9):887-910. 10.1177/0191453717702800 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ford CL., Griffith DM., Bruce MA., Gilbert KL, eds. Racism: Science and Tools for the Public Health Professional. APHA Press; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Jenkins WC., Schoenbach VJ., Rowley DL., Ford CL. Overcoming the impact of racism on the health of communities: what we have learned and what we have not. In: Ford CL., Griffith DM., Bruce MA., Gilbert KL., eds. Racism: Science and Tools for the Public Health Professional. APHA Press; 2019:15-45. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Krieger N. Does racism harm health? Did child abuse exist before 1962? On explicit questions, critical science, and current controversies: an ecosocial perspective. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(2):194-199. 10.2105/AJPH.93.2.194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Krieger N., Rowley DL., Herman AA., Avery B., Phillips MT. Racism, sexism, and social class: implications for studies of health, disease, and well-being. Am J Prev Med. 1993;9(6 Suppl):82-122. 10.1016/S0749-3797(18)30666-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ford CL., Airhihenbuwa CO. Critical race theory, race equity, and public health: toward antiracism praxis. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(S1):S30-S35. 10.2105/AJPH.2009.171058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Williams DR., Collins C. Racial residential segregation: a fundamental cause of racial disparities in health. Public Health Rep. 2001;116(5):404-416. 10.1016/S0033-3549(04)50068-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Nazroo JY. The structuring of ethnic inequalities in health: economic position, racial discrimination, and racism. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(2):277-284. 10.2105/AJPH.93.2.277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Krieger N. Methods for the scientific study of discrimination and health: an ecosocial approach. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(5):936-944. 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300544 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Institute of Medicine Committee on Educating Public Health Professionals for the 21st Century . History and current status of public health education in the United States. In: Gebbie K., Rosenstock L., Hernandez L., eds. Who Will Keep the Public Healthy? Educating Public Health Professionals for the 21st Century. National Academies Press; 2003:41-60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Flexner A. Medical education in the United States and Canada. From the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching, bulletin number four, 1910. Bull World Health Organ. 2002;80(7):594-602. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Welch WH., Rose W. Institute of Hygiene, presented to the General Education Board, May 27, 1915. RF, RG 1.1, Series 200L, Box 183, Folder 2208, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- 15. Fee E. The Welch–Rose Report: Blueprint for Public Health Education in America. Delta Omega Honorary Public Health Society; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Steinecke A., Terrell C. Progress for whose future? The impact of the Flexner Report on medical education for racial and ethnic minority physicians in the United States. Acad Med. 2010;85(2):236-245. 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181c885be [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Morehouse School of Medicine . M.P.H. program overview. Accessed August 13, 2020. https://www.msm.edu/Education/MPH/ProgramOverview.php

- 18. Stefkovich JA., Leas T. A legal history of desegregation in higher education. J Negro Educ. 1994;63(3):406-420. 10.2307/2967191 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Thomas KK. Dr. Jim Crow: The University of North Carolina, the regional medical school for negroes, and the desegregation of southern medical education, 1945-1960. J Afr Am Hist. 2003;88(3):223-244. 10.2307/3559069 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Thomas KK. Health and Humanity: A History of the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, 1935-1985. Johns Hopkins University Press; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Airhihenbuwa CO., Iwelunmor JI. A call for leadership in tackling systemic and structural racism in the academy. In: Ford CL., Griffith DM., Bruce MA., Gilbert KL., eds. Racism: Science and Tools for the Public Health Professional. APHA Press; 2019:97-109. [Google Scholar]

- 22. American Public Health Association . Research and intervention on racism as a fundamental cause of ethnic disparities in health. Am J Public Health. 2001;91(3):515-516. 10.2105/AJPH.91.3.515 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. American Public Health Association . Public health code of ethics. Accessed July 30, 2020. https://www.apha.org/-/media/files/pdf/membergroups/ethics/code_of_ethics.ashx

- 24. Council on Education for Public Health . Accreditation criteria: schools of public health & public health programs. 2016. Accessed July 30, 2020. https://ceph.org/assets/2016.Criteria.pdf

- 25. Hasson RE., Rowley DL., Blackmore Prince C., Jones CP., Jenkins WC. The Society for the Analysis of African-American Public Health Issues (SAAPHI). Am J Public Health. 2014;104(11):2072-2075. 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301672 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Brottman MR., Char DM., Hattori RA., Heeb R., Taff SD. Toward cultural competency in health care: a scoping review of the diversity and inclusion education literature. Acad Med. 2020;95(5):803-813. 10.1097/ACM.0000000000002995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Price EG., Beach MC., Gary TL. et al. A systematic review of the methodological rigor of studies evaluating cultural competence training of health professionals. Acad Med. 2005;80(6):578-586. 10.1097/00001888-200506000-00013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Browne T., Pitner R., Freedman DA. When identifying health disparities as a problem is a problem: pedagogical strategies for examining racialized contexts. J Prev Interv Community. 2013;41(4):220-230. 10.1080/10852352.2013.818481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. McGrath MM. How we measure survival: narratives of Africa in the public health classroom. Afr Today. 2019;65(4):137-157. 10.2979/africatoday.65.4.09 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Tettey N-S. Teaching health disparities, the social determinants of health, and the social ecological model through HBO’s The Wire . J Health Educ Teaching. 2018;9(1):27-36. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Buttress A., German D., Holtgrave D., Sherman SG. The Wire and urban health education. J Urban Health. 2013;90(3):359-368. 10.1007/s11524-012-9760-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Garcia AN., Castro MC., Sánchez JP. Social and structural determinants of urban American Indian and Alaska Native health: a case study in Los Angeles. MedEdPORTAL. 2019;15:10825. 10.15766/mep_2374-8265.10825 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Dennis SN., Gold RS., Wen FK. Learner reactions to activities exploring racism as a social determinant of health. Fam Med. 2019;51(1):41-47. 10.22454/FamMed.2019.704337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Mogford E., Gould L., Devoght A. Teaching critical health literacy in the US as a means to action on the social determinants of health. Health Promot Int. 2011;26(1):4-13. 10.1093/heapro/daq049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hagopian A., West KM., Ornelas IJ., Hart AN., Hagedorn J., Spigner C. Adopting an anti-racism public health curriculum competency: the University of Washington experience. Public Health Rep. 2018;133(4):507-513. 10.1177/0033354918774791 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Rosales CB., Coe K., Ortiz S., Gámez G., Stroupe N. Social justice, health, and human rights education: challenges and opportunities in schools of public health. Public Health Rep. 2012;127(1):126-130. 10.1177/003335491212700117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Taualii M., Delormier T., Maddock J. A new and innovative public health specialization founded on traditional knowledge and social justice: Native Hawaiian and Indigenous health. Hawaii J Med Public Health. 2013;72(4):143-145. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Chávez V., Turalba RAN., Malik S. Teaching public health through a pedagogy of collegiality. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(7):1175-1180. 10.2105/AJPH.2005.062950 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Jones CP. Levels of racism: a theoretic framework and a gardener’s tale. Am J Public Health. 2000;90(8):1212-1215. 10.2105/ajph.90.8.1212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Commission on Social Determinants of Health . Closing the Gap in a Generation: Health Equity Through Action on the Social Determinants of Health. Final Report of the Commission on Social Determinants of Health. World Health Organization; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Calhoun JG., Wrobel CA., Finnegan JR. Current state in U.S. public health competency-based graduate education. Public Health Rev. 2011;33(1):148-167. 10.1007/BF03391625 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ablah E., Biberman DA., Weist EM. et al. Improving global health education: development of a global health competency model. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2014;90(3):560-565. 10.4269/ajtmh.13-0537 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Merzel C., Halkitis P., Healton C. Pedagogical scholarship in public health: a call for cultivating learning communities to support evidence-based education. Public Health Rep. 2017;132(6):679-683. 10.1177/0033354917733745 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Leider JP., Plepys CM., Castrucci BC., Burke EM., Blakely CH. Trends in the conferral of graduate public health degrees: a triangulated approach. Public Health Rep. 2018;133(6):729-737. 10.1177/0033354918791542 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Leider JP., Castrucci BC., Plepys CM., Blakely C., Burke E., Sprague JB. Characterizing the growth of the undergraduate public health major: U.S., 1992-2012. Public Health Rep. 2015;130(1):104-113. 10.1177/003335491513000114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Metzl JM., Petty J., Olowojoba OV. Using a structural competency framework to teach structural racism in pre-health education. Soc Sci Med. 2018;199:189-201. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.06.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Metzl JM., Hansen H. Structural competency: theorizing a new medical engagement with stigma and inequality. Soc Sci Med. 2014;103:126-133. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.06.032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Morris JE., Cribb Fabersunne C., Scott N., Saldaña F. Teaching to undo structural racism. Med Educ. 2018;52(5):552-553. 10.1111/medu.13550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Sacks T., Jacobs L. Introduction to the special issue on structural competency. J Sociol Soc Welf. 2019;46(4). [Google Scholar]

- 50. Hayman K., Wen M., Khan F., Mann T., Pinto AD., Ng SL. What knowledge is needed ? Teaching undergraduate medical students to “go upstream” and advocate on social determinants of health. Can Med Educ J. 2019;11(1). 10.36834/cmej.58424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. LaVeist TA. Minority Populations and Health: An Introduction to Health Disparities in the United States. Jossey-Bass; 2005. [Google Scholar]