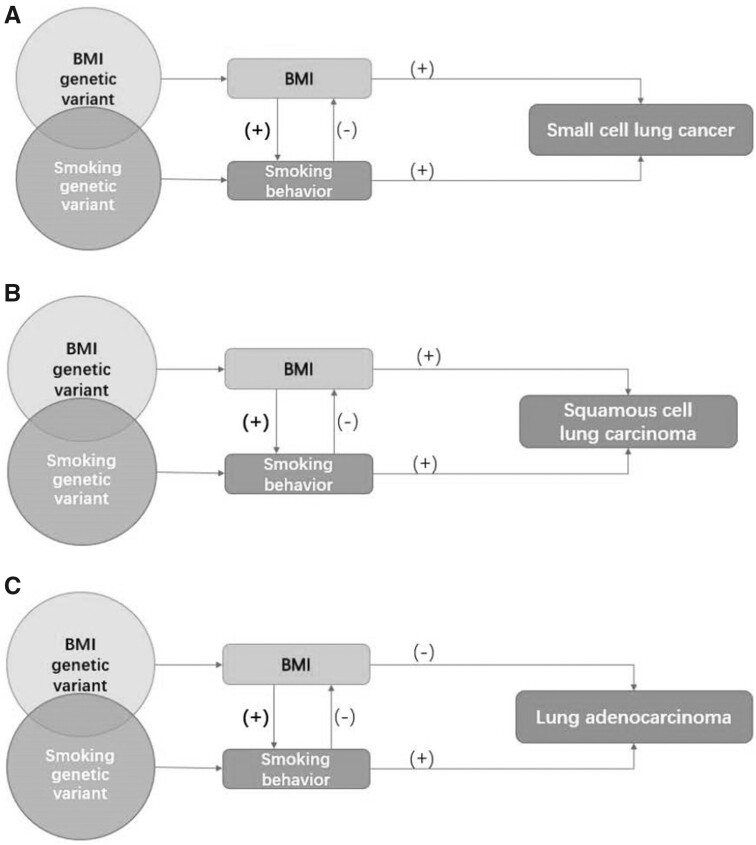

Figure 2.

Associations between obesity, smoking, and risk of lung cancer subtypes. A) Illustration of the association between obesity, smoking, and small cell lung cancer risk. B) Illustration of the association between obesity, smoking, and squamous cell lung carcinoma risk. C) Illustration of the association between obesity, smoking, and lung adenocarcinoma risk. Genetically predicted body mass index (BMI) was positively associated with the number of cigarettes smoked per day; on the contrary, genetically predicted and observed smoking is associated with lower BMI. The bold (+) implies a much stronger path from BMI to smoking phenotypes rather than from smoking to BMI. From this perspective, the presence of smoking can either violate the independence assumption (single variant polymorphisms [SNP]s used are not associated with confounders, such as smoking) or the exclusion restriction assumption (SNPs used affect the outcome only through the effect on BMI) that underpin Mendelian randomization (MR) studies. Using multivariable MR analyses controlling for smoking, the findings that BMI was positively associated with risk of small cell lung cancer but inversely associated with lung adenocarcinoma in MR studies are in accordance with conventional observational studies that carefully address reverse causality and confounding by smoking. For squamous cell carcinoma, a subtype that is most strongly influenced by smoking, MR studies that have advantages in minimizing confounding bias find a positive association, whereas the inverse association observed in conventional observational studies is likely to result in a negative (residual) confounding by smoking.