Abstract

Background:

Despite emphasis on efforts to prevent cardiovascular disease (CVD), 13–34% of people never fill a prescribed statin (primary nonadherence). This study determined perceptions of adults with primary nonadherence to statins.

Methods:

Ten focus groups were conducted with 61 adults reporting primary nonadherence to statins (93% without known CVD). Participants were recruited from an academic medical center and nationwide Internet advertisements.

Results:

Major themes related to primary nonadherence were: 1) desire to pursue alternatives before starting a statin (e.g., diet and/or exercise, dietary supplements); 2) worry about risks and adverse effects of statins; 3) perceptions of good personal health (suggesting that a statin was not needed); and 4) doubt about the benefits of statins in the absence of disease. Additional themes included mistrust of the pharmaceutical industry, mistrust of prescribing providers, inadequate provider communication about statins, and negative prior experiences with medication. Though rare, a few patients said that high cholesterol does not require treatment if it is genetic. One-third noted during focus group discussions that they did not communicate their decision not to take a statin to providers.

Conclusions:

Adults with primary nonadherence to statins describe seeking alternatives, avoiding perceived risks of statins, poor acceptance/understanding of CVD risk estimates, and doubts about the benefits of statins. Many do not disclose their decisions to providers, thus highlighting the need for provider awareness of the potential for primary nonadherence at the point of prescribing, and the need for future work to develop strategies to identify patients with potential primary nonadherence.

Keywords: Medication adherence, statins, primary nonadherence, qualitative research

INTRODUCTION

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the United States’ leading cause of morbidity, mortality, and rising health care costs,1 but proven population-based CVD risk reduction strategies are often not fully used. Many organizations seek to reduce CVD risk factors such as high cholesterol.2–8 Patients not meeting goals after lifestyle modification are prescribed HMGCoA reductase inhibitors, commonly referred to as “statins,” for CVD prevention.9,10 But patients often do not take statins as prescribed. Secondary nonadherence (stopping or taking a medication differently than prescribed) is a recognized problem,11,12 but it is less well recognized that 13–34% of people never fill a new statin prescription (primary nonadherence).13–18

While existing studies have identified the incidence and demographics associated with primary nonadherence, none have exclusively explored the reasons, attitudes and beliefs behind primary statin nonadherence. This study aims to address this gap in understanding. Previous studies in the United States, all from one managed care healthcare system, suggest that patients with primary nonadherence tend to be English-speaking, younger, black, on no other medications, and have fewer comorbidities,17–19 suggesting that they were prescribed statins for primary prevention. One study showed that most respondents had “general concerns” about statins, were scared of side effects, or failed to understand why statins were prescribed or their purpose.17 Outside of these findings, the literature lacks a deeper understanding of the attitudes and beliefs of patients with primary statin nonadherence, the information patients consider before deciding not to start statins, or how primary statin nonadherence might be avoided. This focus group study was designed to investigate attitudes, beliefs, and perceptions of patients who chose not to fill their first prescription for a statin.

METHODS

Participant Identification and Recruitment

Participants were recruited from: 1) lists of patients with primary nonadherence at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), identified by querying electronic health records linked to Surescripts medication fill data;20 2) placing internet advertisements on Craigslist.com in 22 United States metropolitan areas over a 6-month period; and 3) a large internet-based CVD cohort (the Health eHeart Study). Advertisements contained a link to a study information sheet and to an eligibility screening questionnaire; the study team contacted potentially eligible participants.

Eligibility criteria were: aged 18 and older, received a new statin prescription within 2 years prior to contact, and did not start taking the prescription. We oversampled for minority patients. The UCLA Institutional Review Board (IRB) approved the study protocol, and served as the IRB of record for the University of California, San Francisco. No written informed consent was required, but participants gave verbal consent prior to the focus groups.

Data Collection

Focus groups were conducted between February and July 2018 by two project coordinators with psychology backgrounds who were experienced interviewers. We chose interviewers without medical backgrounds to lead the focus groups so that patients would not feel inhibited sharing their honest opinions about their medical care. To minimize variation in technique, both interviewers were thoroughly oriented to the research problem, participated in developing the interview guide and potential probes, and engaged in debriefing sessions after each focus group. A physician-investigator with expertise conducting focus group interviews concerning patient medication use21–24 was present for all but one focus group discussion, and worked with the interviewers to probe participant perspectives. To avoid influencing patient responses, this investigator was introduced only by first name, and patients were informed only that the investigator was a research team member. Focus groups lasted a mean of 80.2 (SD=11.1) minutes and were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Interviewers used a focus group discussion guide to lead conversations and probed participants as needed for detailed answers. Interviewers met with two of the investigators (JBS [a cardiologist] and DMT [a family physician]) after each focus group to reflect on interview findings, put them into context of earlier focus group discussions, and to modify the focus group guide as needed to prompt greater depth of responses (Table 1).25,26 All participants were surveyed about their demographics; history of heart disease/heart attack, stroke, or diabetes; and number of prescription medications taken. Participants received a $60 gift card for participating.

Table 1.

Sample Focus Group (FG) Interview Guide

| • Think back to why you didn’t get your statin medicine. What sorts of things kept you from getting it? |

| • Tell us about your interaction with your doctor when s/he prescribed the statin. |

| • What would have led you to fill the statin prescription when your doctor prescribed it? |

| • What might lead you to get the statin medicine in the future? |

| • Where do you get most of your information about statin medicines? |

Focus Group Analyses

Four investigators with different backgrounds (family physician with expertise in physician-patient communication, medical sociologist, cardiologist, and project coordinator with psychology background) formed the coding team. On completion of data collection, they independently reviewed a subset of two focus group transcripts, using inductive content analysis,27,28 existing literature,29 and clinical expertise to generate themes. The coders used open coding to identify comments in focus group discussions that related to patient decisions about not starting a prescribed statin. Themes were classified as “major themes” if they emerged in every focus group discussion, and as “minor themes” if they were raised in only a subset of discussions. Subthemes (specific themes within major and minor themes) also were identified. The coding team engaged in discussions about the themes, resolved disagreements via consensus, and generated a codebook describing the themes. After theme generation, 3 coders performed focused coding using the codebook, with at least 2 coders analyzing each transcript. Coding discrepancies were resolved through discussion. ATLAS.ti 8.0 (Scientific Software Development GmbH) was used for coding. Theoretical saturation, when no new themes can be generated from the data, was reached after eight transcripts. This was assessed by using ATLAS.ti to track the codes applied to each transcript.

RESULTS

Ten focus groups were conducted with 61 total participants. Participants were mostly middle-aged and without CVD (Table 2). All participants met screening criteria for primary nonadherence to statins within the past 2 years, but it became apparent during the discussions that 4 participants (in 3 focus groups) had taken statins in the distant past.

Table 2.

Focus group patient characteristics; n=61

| Characteristic | n (%) or mean (SD) |

|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD), range | 53.0 (10.2), 25–75 |

| Female, n (%) | 33 (54.1) |

| Race/ethnicity, n (%) | |

| White | 20 (32.8) |

| Black | 18 (29.5) |

| Hispanic | 16 (26.2) |

| Asian | 5 (8.2) |

| Mixed race | 2 (3.3) |

| History of diabetes, n (%) | 10 (16.4) |

| History of heart attack, n (%) | 4 (6.6) |

| History of stroke, n (%) | 0 |

| Prescription medications taken, mean (SD), range | 1.4 (1.8); 0–7 |

| Not taking any prescription medications | 27 (44.3) |

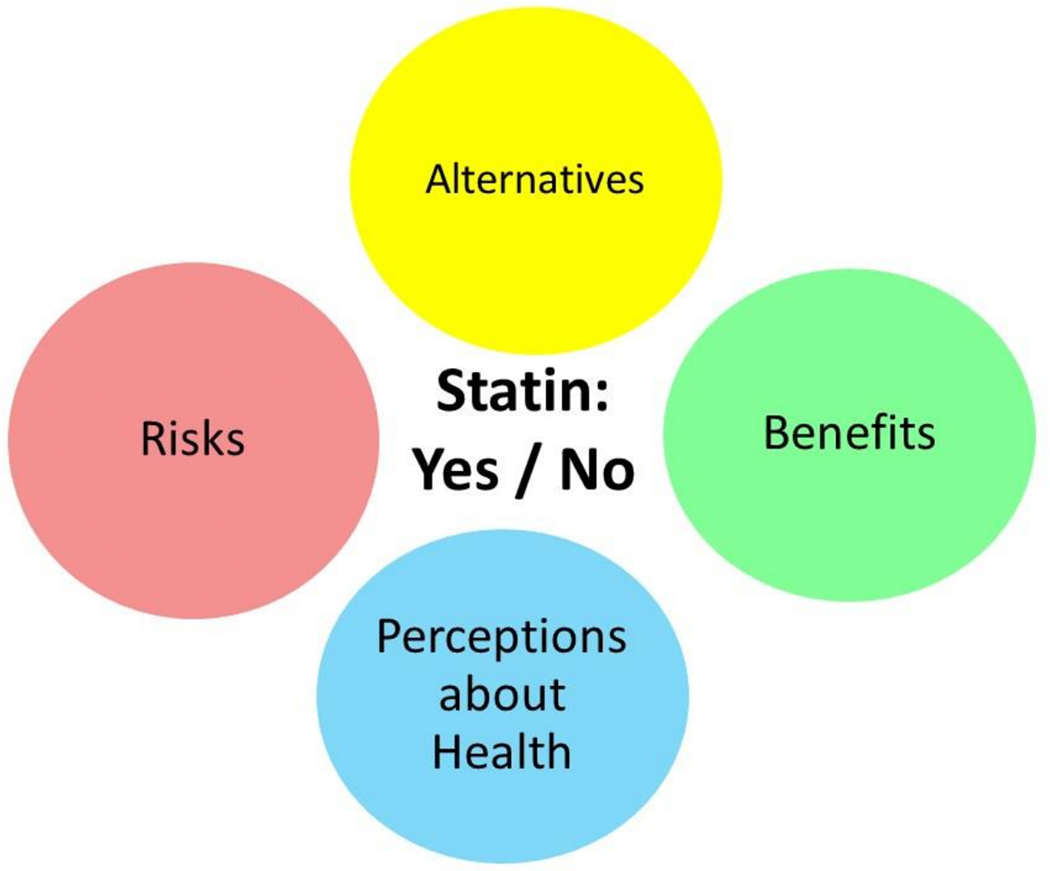

Four major themes describing patient perspectives about starting a statin medication emerged from all focus group discussions: 1) desire for alternative treatments; 2) worry about the risks of statins; 3) perceptions of good personal health; and 4) uncertainty about the benefits of statin use. We also present “minor themes” that emerged from some but not all focus group discussions, as well as themes related to provider-patient relationships and interactions that influenced patient decisions about starting a statin. Below we describe each of the major themes in detail (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Framework describing major categories of information patients consider when newly prescribed a statin medication

Major Themes Related to Primary Statin Nonadherence (Table 3)

Table 3.

Sample Quotations Depicting the Subthemes Associated with Each Major Theme Influencing Primary Statin Nonadherence

| Major Themes and Associated Subthemes | Sample Quotes |

|---|---|

| Desire for Alternative Treatments | |

| Lifestyle changes (diet and exercise) | “I actually informed my doctor that I wasn’t gonna take it, but he can prescribe it to me first, but I wanted to go to changing my diet first to see if that would help.” [FG5:P1] |

| Dietary supplements / alternative treatments | I think if you look up a bunch of your herbs, herbs that you can eat…that will also help. Natural herbs. [FG6:P1] |

| Risks | |

| Risks of statins worry patients | |

| Side effects and interactions | “I don’t [want to] have liver and kidney problems, and muscle cramp[s], and all those crazy side effects.” [FG5:P4] |

| Worsening of existing problems | “Some of my friends and…me, I have asthma. They had took statin and they had more symptoms. It worsened their lung functions… yeah, it made it worse. Worsened their lungs.” [FG6:P3] |

| Creating new medical problems | “The last thing I wanted to do was to get type 2 diabetes while trying to lower my cholesterol. So it just seemed counterproductive [FG9:P1] |

| Causing addiction or dependency | “ I didn’t know if this is something that you can get addicted to or something like that.” [FG6:P4] |

| Perceptions of Good Health | |

| Too healthy or young to start a statin | “Made me feel old, you know. I always thought statins would be for older people like, retirees, versus someone in their 40s.” [FG3:P2] |

| Good family history | “My mother had the same lipid profile I have, and they wanted to put her on a statin. And I think she did it for a while, but – without it, though, she hit 93.” [FG1:P3] |

| Cholesterol slightly high or not that high | “I’m not that over the scale that I should have to be taking [a statin] … I’m only eight points over.” [FG2:P4] |

| Correctable reason for high cholesterol | “…my cholesterol was just over the normal, and I had lost my mother so I gained some weight…” [FG3:P5] |

| High cholesterol is genetic | “I heard my family mention that they also have the same issue with the high cholesterol. They were told that it was genetic and basically they were told that it didn’t matter if they took the medication…Basically, the medication wasn’t going to help. So I figure if it’s a genetic thing, why even take the medication?” [FG10:P1] |

| Benefits – Uncertainty about benefits | |

| Scientific evidence not definitive | “…the other key point from that [JAMA] article was that there was not as strong evidence that it really…that everybody would really need it even though it was being recommended under the new guidelines.” [FG7:P6] |

| Risk calculator does not look at people as individuals | “…we’re being treated by a medical profession that sees us sort of as a statistic. I mean, statistically speaking, you have a 10 percent chance of having a cardiac event in the next blah-blah-blah. And we’re not all the same.” [FG1:P4] |

| Link between cholesterol and CVD is uncertain | “…it’s not really clear how important is it to take statins, in spite of having a so called high level of bad cholesterol.” [FG2:P1] |

| Cholesterol cutoffs for treatment are arbitrary | “I’m not going to take [a statin] for what could be just an arbitrary number.” [FG4:P5] |

| Statins do not cure | “…we have to make changes in our life…Medication is not a cure. It’s just a band aid.” [FG4:P7] |

Desire for Alternative Treatments

Almost all participants expressed a desire to pursue alternative treatments before starting a statin. Alternatives ranged from lifestyle changes (e.g., exercise, dietary changes, weight loss) to dietary supplements and “home remedies.” Participants often mentioned wanting ‘natural’ treatments such as red yeast rice, vitamin E, and cinnamon. One participant noted: “…as an alternative, I have bought an over-the-counter plant sterol gummy and I’ve been taking the gummies for awhile.” [FG8:P3] Another participant’s experience involved visiting: “a health food store, and they recommended some herbs to take, like garlic, fenugreek, turmeric, ginger, omega-3, flaxseed…I’ll make a smoothie every other day and include the herbs.” [FG4:P7] Home remedies included boiling avocado leaves and drinking the resultant tea. Other approaches included yoga and following a holistic lifestyle.

Participants mostly felt no urgency to start statins. In addition to wanting alternatives, some wanted to repeat their cholesterol test, do other additional testing, or get more information about statins. Many stated they were willing to start a statin if alternative treatments were ineffective.

Worry about the Risks of Statins

Almost all focus group participants worried about statin side effects (e.g., liver damage, muscle pain), which they typically read about on the internet or heard about from friends or family. Participants also had concerns about worsening existing medical issues and about potential interactions with other medications, for example: “Because if you’re on a lot of medications…it seems like it conflicts a bit.” [FG9:P4]. Some were apprehensive about creating new problems, for example: “Problem that I see, it causes like a domino effect. You take one medication for one thing, and it causes something else to happen, so then you have to take another medication to counteract the problem that the side effect is causing.” [FG2:P5] Those with a family history of diabetes were particularly concerned about statin use leading to diabetes.

Perceptions of Good Personal Health

There were several subthemes describing participant perceptions of personal health. A few participants felt that statins were unwarranted because they had no medical problems or were too young. Others noted they had a healthy lifestyle, no family history, or no symptoms. Some said immediate statin use was unwarranted because their cholesterol was only slightly above normal, for example, “I found myself healthy. Just a little change in the cholesterol. It doesn’t mean I have to start [a statin].” [FG7:P4]

Almost all indicated they would start a statin in a “life or death” or “life-threatening” situation. Some said they would consider a statin if their cholesterol became “really high,” if they had worsening health, or they started eating more unhealthy foods. One participant noted, “If I knew that I was in serious probability of having [a heart attack], I would probably think twice about taking it.” [FG9:P2] Many said they would take a statin if they had a heart attack, stroke, or heart disease.

Uncertainty about the Benefits of Statin Use

Some participants seemed to have a poor understanding about the benefits of statins. For example, a participant with heart disease revealed a disconnect: “If there’s a medication that I could take that would help with my heart problem and prolong my life, you know, that’s a no-brainer. You take it.” [FG7:P5]

Some participants correctly noted that statins lower cholesterol levels. But many questioned the benefits of statins, with some asserting that statins are not that helpful or important, and others suggesting that the evidence for use is unclear: “even though medical studies say that…the benefits will be such in such, what it turns out that in many cases that is wrong, and on later stud[ies] that information is wrong” [FG3:P6]. A handful were unconvinced that 10-year cardiovascular event risk calculators appropriately incorporated their personal characteristics. A minority questioned the link between cholesterol and CVD. Several also felt that cholesterol treatment cutoffs were arbitrary. Participants mostly failed to understand the concept of personal risks for CVD; discussions often turned to the risks of statins when the term “risk” was mentioned.

Minor Themes Related to Primary Statin Nonadherence

Participant Hesitation about Medication Use

Many participants generally resisted taking medications. Those already taking medications hesitated to add another prescription. Some felt that taking too many medications was detrimental. Those naïve to chronic medications were resistant to starting one. Two patients conceded they were in denial; one acknowledged: “I’m kind of like more in denial. By taking [a statin], I’m admitting I have a problem.” [FG10:P2] One patient mentioned: “I wanted to avoid having that stigma of having to go on Lipitor. I mean, to me, there’s a stigma, maybe kind of some type of judgment that others make when they would find out.” [FG7:P3] Some felt that medications were overprescribed, with doctors tending to pursue a “quick fix” [FG6:P7]. Other participants talked about not wanting a daily medication, feeling hesitant about taking a medication for the rest of their life, or dosing regimens that were difficult for them to follow.

Prior experiences contributed to hesitation to take statin

Prior experiences that influenced participants included experiencing adverse medication effects, hearing about others’ negative experiences with medications, or having prior success lowering cholesterol with non-pharmaceutical therapies. As one participant noted: “there’s other drugs that I’ve taken that have had side effects, and so I just don’t need another drug that has side effects.” [FG1:P2]

Mistrust of pharmaceutical industry

Participants in 8 of 10 groups voiced concerns about pharmaceutical companies influencing prescribing: “I’m inclined to think…that some doctors are paid commissions for prescribing medicines, their medicines, by their pharmaceutical companies.” [FG8:P2] Another participant noted: “I can be cynical enough to think that the pharmaceutical marketing may actually impact the guidelines. You and I all know that they’ve been milking millions of dollars, pouring into vacations and cars…and I don’t know who writes those ever-changing opinions about when should somebody start [a statin]…” [FG1:P2]

Medication Cost

Only a handful of participants cited cost as the primary reason they failed to fill their statin prescription. High costs mostly served to reinforce participants’ hesitation, for example: “I had to come out-of-pocket for $75.00. I was like, no, I’m not going to do that. I think that if I go natural, I will feel much better. I will put less side effects on my body and I will have to pay less.” [FG10:P3]

Themes Related to Provider-Patient Relationships and Interactions

Mistrust of prescribing provider

Several participants felt unsure about starting a statin because it was prescribed by a provider they had never seen. Others wanted their primary care provider’s approval before starting the statin: “I didn’t feel like the hospital cardiologist was equipped or knew enough about me to prescribe medication to me other than my PCP.” [FG10:P2] Poor provider-patient relationships and mistrust also contributed to primary nonadherence.

Inadequate provider communication about statins

Communication lapses were important. One patient shared that his doctor “…didn’t even say anything, just told that they were sending me the pills.” [FG5:P5] Lack of shared decision-making deterred patients from filling statins, as did patient perceptions that providers did not care or were not very worried about a patient’s cholesterol. Two patients did not realize their provider prescribed a statin until their pharmacy notified them. As one described: “I got a notice on my cell phone, a text message, that I had another prescription and I was confused. He had sent, this doctor, which I’d never seen before, had sent a prescription for Lipitor [to the pharmacy], which I didn’t fill because I felt like I wasn’t informed. I didn’t know what it was for.” [FG7:P2]

Participant Comments on Disclosing Nonadherence to Providers

During focus group discussions, not all participants commented about disclosing their nonadherence, but 20 of 61 participants stated that they had not told their providers about their primary nonadherence. Half of these participants were planning on telling their provider, but a few believed it was disrespectful to question their provider’s recommendations, and were hesitant to bring up their primary nonadherence. Of 26 participants who told a provider about their primary nonadherence, 19 (73.1%) indicated their hesitation at the time of prescribing and the rest during a follow-up visit.

“We’re Not All the Same”

One focus group participant summarized the need for providers to individualize approaches when prescribing statins, by addressing aspects of the major themes that might prevent patients from starting a statin:

“Some people just get that prescription, go and pop the pill, and they’re done. Other people need an explanation…need to understand what all the ramifications are if I do this and if I don’t do that and so on. And so you have to, as a medical professional, adjust the way you approach your patient. And so, if you see someone’s reluctant, you have to be able to either explain it in a way – if you really believe that this would benefit the person, explain it in a way that they are, let’s say, convinced, which is maybe too strong a word, or demonstrate it by doing other tests and giving some more data because…we’re not all the same. Different people need different information.” [FG1:P4]

DISCUSSION

The focus group interviews in this study elucidated why adults might choose primary nonadherence to statins. Participants discussed four major themes influencing their decisions: 1) desire for alternative treatments; 2) worry about the risks of statins; 3) perceptions of good personal health; and 4) uncertainty about the benefits of statin use. Existing literature shows that patients in general do not wish to take new medications, and may go to extremes to avoid using them.30 Many themes identified in this study echoed those found in other studies examining patient perspectives towards statins and on reasons underlying nonadherence to other medications such as anti-hypertensive drugs.31,32 However, with its focus on primary nonadherence to statins (mostly for primary CVD prevention), this study goes beyond the existing literature by illustrating that primary nonadherence to statin medications reflects a decision-making process that is weighted toward belief in individual ability to alter lifestyle, diet, or exercise to reduce cholesterol levels, and minimization of personal risk and the potential benefit of a statin in the absence of symptomatic conditions/disease. Laboratory cutoff points and guideline-based risk assessments did not appear to convince participants that a statin medication was necessary.

It makes intuitive sense that people who perceive themselves to be at low risk for an adverse medical outcome may want to delay starting a newly prescribed chronic medication and to first try alternative measures. While we did not examine participant medical records or calculate CVD risks, limited medication use and young mean age of participants support their lack of reported CVD. Participant preferences for lifestyle or dietary modifications align with most guidelines recommending initial primary prevention in people with high cholesterol without CVD.3,6 It is reassuring that most participants would reconsider statin use if their efforts failed to lower their cholesterol, if their cholesterol levels increased, or if they developed CVD. Thus, this decision may be mutable but may require time for individuals to process information or try alternatives. Providers need to find better ways to convey concepts regarding CVD risk, achievable goals from lifestyle modification, and the lack of evidence for dietary supplements in improving CVD risk, as well as the evidence of benefits of statins. Discussions about 10-year risk calculators may need proper context and framing for patients who worry mostly about their immediate risks for adverse outcomes.

One-third of all focus group participants did not inform their providers about their nonadherence to the statin. This finding is limited and requires additional exploration because not all participants commented on this topic. In the absence of this communication, there is no opportunity to address poor understanding about the role of statins for primary prevention of CVD, the risks of statin therapy and ways to monitor or minimize them, or the opportunity to develop a plan to reduce their cardiovascular risk over time.

Previous studies have shown lapses in provider communication around newly prescribed medications.33,34 In this study, some participants revealed that gaps in communication contributed to their unwillingness to start a statin. Providers often are reluctant to question or confront patients about nonadherence,23 but our data suggest that it is important to assess a patient’s stance toward statins at the time of prescribing, to make sure patients know providers are considering their individual situations, to tailor discussions to address individual patient concerns, and to ensure that patients have follow-up appointments to assess adherence. Reluctant patients would likely benefit from a trial of lifestyle or dietary changes, or other preferred treatment modalities. Providers could employ discussions regarding the duration and goals of the trial. Follow-up visits would ascertain success in meeting goals, address individual patient concerns about the benefits and risks of statins, and help patients better understand their personal risks for cardiovascular events.35 If goals were met in the short-term, a plan for future reassessment could be established.

Mistrust was commonly raised during the focus group discussions. Mistrust of the pharmaceutical industry led some participants to question the validity of scientific guidelines, and even their providers’ motives for prescribing statins. This erosion of trust likely influences people’s ability to trust that population-based guidelines apply to individuals, and to accept that the benefits of statins outweigh the risks. Thus, for some patients, restoring trust in the pharmaceutical industry or strengthening trust in their physician may be crucial to their acceptance of treatments that are beneficial to their health.

Study limitations include those inherent to focus group studies, such as potential lack of transferability due to participant self-selection.36 EHR identification of patients with primary nonadherence was inaccurate and yielded insufficient numbers of patients for purposive sampling based on patient characteristics. Thus most of our participants were recruited from online advertisements, and the majority of the participants used the internet. However, internet usage is growing, with 87% and 66% of adults aged 50–64 and aged 65+, respectively, using the internet in 2018.37 We discovered during focus group discussions that a small number of participants in 3 focus groups had secondary, rather than primary nonadherence. All of the themes raised by these patients were consistent with those mentioned by patients with primary nonadherence. The majority of patients in this study were prescribed a statin for primary, rather than for secondary CVD prevention, so additional studies may be needed to assess potential differences in attitudes of those prescribed a statin for secondary prevention.

In conclusion, this study describes patients’ wishes to choose their own lifestyle or dietary changes, their concerns regarding the risks of statins, and their lack of understanding of personal risks necessitating statin use and potential benefits of statin therapy as major contributors to primary nonadherence to statins in people without CVD. In addition, we found that patients often do not communicate their decision not to take a statin to their providers. The work identifies promising targets for improvement that could help reduce cardiovascular risks.

Acknowledgements.

The authors appreciate the assistance of Maria Cornejo-Guévara for her help conducting focus groups and Althea Miller for providing feedback on focus group guides.

Funding. This project was supported by: 1) National Institutes of Aging (NIA) grant 1R21AG055832, 2) NIH/NIDDK K24DK102057 (Dr. Fernandez), and 3) National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, through UCLA CTSI Grant Number UL1TR001881. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH or NIA.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest. Drs. Tarn and Schwartz have been funded by the BMS/Pfizer Alliance ARISTA-USA to conduct unrelated research studies. Dr. Schwartz presented at a National Institutes of Aging advisory workshop on statins, is on advisory boards for Bristol Myers Squibb and Pfizer for unrelated work, and has received grant funding from Future Diagnostics for vitamin D research. Ms. Barrientos, Dr. Pletcher, Mr. Cox, Dr. Turner and Dr. Fernandez report no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, Go AS, et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2016 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2016;133(4):e38–e360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lloyd-Jones DM, Hong Y, Labarthe D, et al. Defining and setting national goals for cardiovascular health promotion and disease reduction: the American Heart Association’s strategic Impact Goal through 2020 and beyond. Circulation. 2010;121(4):586–613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grundy SM, Stone NJ, Bailey AL, et al. 2018 AHA/ACC/AACVPR/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ADA/AGS/APhA/ASPC/NLA/PCNA Guideline on the Management of Blood Cholesterol: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2019;139(25):e1082–e1143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grundy SM, Stone NJ, Bailey AL, et al. 2018 AHA/ACC/AACVPR/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ADA/AGS/APhA/ASPC/NLA/PCNA Guideline on the Management of Blood Cholesterol: Executive Summary: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2019;139(25):e1046–e1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grundy SM, Stone NJ, Bailey AL, et al. 2018 AHA/ACC/AACVPR/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ADA/AGS/APhA/ASPC/NLA/PCNA Guideline on the Management of Blood Cholesterol: Executive Summary: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2019;73(24):3168–3209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grundy SM, Stone NJ, Bailey AL, et al. 2018 AHA/ACC/AACVPR/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ADA/AGS/APhA/ASPC/NLA/PCNA Guideline on the Management of Blood Cholesterol: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2019;73(24):e285–e350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Division for Heart Disease and Stroke Prevention. Retrieved on July 26, 2020 from https://www.cdc.gov/cholesterol/

- 8.Healthy People 2020. [Internet]. Heart Disease and Stroke. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Retrieved on July 26, 2020 from: https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/heart-disease-and-stroke. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wilson PWF, Polonsky TS, Miedema MD, Khera A, Kosinski AS, Kuvin JT. Systematic Review for the 2018 AHA/ACC/AACVPR/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ADA/AGS/APhA/ASPC/NLA/PCNA Guideline on the Management of Blood Cholesterol: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2019;139(25):e1144–e1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wilson PWF, Polonsky TS, Miedema MD, Khera A, Kosinski AS, Kuvin JT. Systematic Review for the 2018 AHA/ACC/AACVPR/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ADA/AGS/APhA/ASPC/NLA/PCNA Guideline on the Management of Blood Cholesterol: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2019;73(24):3210–3227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ho PM, Bryson CL, Rumsfeld JS. Medication adherence: its importance in cardiovascular outcomes. Circulation. 2009;119(23):3028–3035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kini V, Ho PM. Interventions to Improve Medication Adherence: A Review. Jama. 2018;320(23):2461–2473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liberman JN, Hutchins DS, Popiel RG, Patel MH, Jan SA, Berger JE. Determinants of primary nonadherence in asthma-controller and dyslipidemia pharmacotherapy. American Journal of Pharmacy Benefits. 2010;2(2):111–118 118p. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Raebel MA, Ellis JL, Carroll NM, et al. Characteristics of patients with primary nonadherence to medications for hypertension, diabetes, and lipid disorders. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(1):57–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shin J, McCombs JS, Sanchez RJ, Udall M, Deminski MC, Cheetham TC. Primary nonadherence to medications in an integrated healthcare setting. Am J Manag Care. 2012;18(8):426–434. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tamblyn R, Eguale T, Huang A, Winslade N, Doran P. The incidence and determinants of primary nonadherence with prescribed medication in primary care: a cohort study. Annals of internal medicine. 2014;160(7):441–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harrison TN, Derose SF, Cheetham TC, et al. Primary nonadherence to statin therapy: patients’ perceptions. Am J Manag Care. 2013;19(4):e133–139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cheetham TC, Niu F, Green K, et al. Primary nonadherence to statin medications in a managed care organization. Journal of managed care pharmacy : JMCP. 2013;19(5):367–373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Derose SF, Green K, Marrett E, et al. Automated outreach to increase primary adherence to cholesterol-lowering medications [Randomized Controlled Trial; Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t]. JAMA internal medicine. 2013;173(1):38–43. doi: 10.1001/2013.jamainternmed.717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.The Surescripts Network Alliance. Retrieved July 26, 2020 from: https://surescripts.com/.

- 21.Tarn DM, Guzman JR, Good JS, Wenger NS, Coulter ID, Paterniti DA. Provider and patient expectations for dietary supplement discussions. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(9):1242–1249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tarn DM, Paterniti DA, Williams BR, Cipri CS, Wenger NS. Which providers should communicate which critical information about a new medication? Patient, pharmacist, and physician perspectives. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57(3):462–469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tarn DM, Mattimore TJ, Bell DS, Kravitz RL, Wenger NS. Provider views about responsibility for medication adherence and content of physician-older patient discussions. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(6):1019–1026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tarn DM, Paterniti DA, Wenger NS, Williams BR, Chewning BA. Older patient, physician and pharmacist perspectives about community pharmacists’ roles. The International journal of pharmacy practice. 2012;20(5):285–293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gubrium JF. The Sage handbook of interview research : the complexity of the craft. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks: SAGE; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gubrium JF, Holstein JA. Handbook of interview research : context & method. Thousand Oaks, Calif.: Sage Publications; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Babbie ER. The basics of social research. Sixth edition. ed. Belmont CA: Wadsworth, Cengage Learning; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Denzin NK, Lincoln YS. The Sage handbook of qualitative research. 4th ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 29.World Health Organization (WHO). Adherence to Long-Term Therapies: Evidence for Action. 2003, Geneva, Switzerland. Retrived on July 26, 2020 from http://www.who.int/chp/knowledge/publications/adherence_report/en/. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Traulsen J, Britten N, J K. Patient perspectives. In: Elseviers BW M, Almarsdottir AB, Andersen M, Benko R, Bennie M, Eriksson I, Godman B, Krska J, Poluzzi E, Taxis K, Vlahovic-Palcevski V, Stichele RV, ed. Drug Utilization Research.2016:347–354. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ju A, Hanson CS, Banks E, et al. Patient beliefs and attitudes to taking statins: systematic review of qualitative studies. The British journal of general practice : the journal of the Royal College of General Practitioners. 2018;68(671):e408–e419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Polinski JM, Kesselheim AS, Frolkis JP, Wescott P, Allen-Coleman C, Fischer MA. A matter of trust: patient barriers to primary medication adherence. Health Educ Res. 2014;29(5):755–763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tarn DM, Heritage J, Paterniti DA, Hays RD, Kravitz RL, Wenger NS. Physician communication when prescribing new medications. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(17):1855–1862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tarn DM, Paterniti DA, Heritage J, Hays RD, Kravitz RL, Wenger NS. Physician communication about the cost and acquisition of newly prescribed medications. Am J Manag Care. 2006;12(11):657–664. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Navar AM, Wang TY, Mi X, et al. Influence of Cardiovascular Risk Communication Tools and Presentation Formats on Patient Perceptions and Preferences. JAMA Cardiology. 2018;3(12):1192–1199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Morgan DL. Focus groups as qualitative research / Morgan David L.. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, Calif.: Sage Publications; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pew Research Center Internet and Technology. Internet Use by Age. Retrieved July 26, 2020 from https://www.pewinternet.org/chart/internet-use-by-age/.