ABSTRACT

A cross-sectional field survey was conducted from November 2020 to January 2021 among 7259 participants to investigate the public perception, willingness, and information sources for COVID-19 vaccination, with the focus on the elderly and non-communicable chronic disease (NCD) population. Multiple logistic regressions were performed to identify associated factors of the vaccination willingness. The willingness rate of the elderly to accept the future COVID-19 vaccine (79.08%) was lower than that of the adults aged 18–59 (84.75%). The multiple analysis didn't identify significant relationship between NCD status and the vaccination intention. The main reasons for vaccine hesitancy by the public were: concern for vaccine safety, low infection risk, waiting and seeing others getting vaccinated, concern of vaccine effectiveness and price. Their relative importance differed between adults aged 18–59 and the elderly, and between adults aged 18–59 with or without NCD. Perception for vaccination importance, vaccine confidence, and trust in health workers were significant predictors of the vaccination intention in both age groups. The elderly who perceived high infection risk or had trust in governments were more likely to accept the vaccine. Compared with the adults aged 18–59, the elderly used fewer sources for COVID-19 vaccination information and more trusted in traditional media and family, relatives, and friends for getting vaccination recommendations. To promote vaccine uptake, the vaccination campaigns require comprehensive interventions to improve vaccination attitude, vaccine accessibility and affordability, and tailor strategies to address specific concerns among different population groups and conducted via their trusted sources, especially for the elderly.

KEYWORDS: COVID-19, vaccine, acceptance, elderly, chronic disease, China

1. Introduction

The Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) pandemic has continued to spread worldwide, imposing enormous disease burdens and severely disrupting social and economic development.1–3 Being regarded as one of the most promising and cost-effective interventions to prevent and control the pandemic, COVID‐19 vaccines have been developed, tested, and put into use at an unprecedented pace.4–6 Since December 2020, many countries, such as Israel, the UK, the USA, and some EU countries, have prepared or launched mass vaccination campaigns with aims to protect key and vulnerable populations (e.g., healthcare workers, the elderly, and patients with chronic diseases) firstly and then achieve herd immunity as soon as possible.7–10 In China, one of the leading countries in developing vaccines against COVID‐19, about 14 vaccines are under development with different technical routes so far, and five of them have entered phase III clinical trials.11 On December 15, 2020, with a few vaccines authorized for limited use, China officially launched a vaccination program targeting several key groups, including cold-chain workers, customs officers, and medical workers.11 On December 30, with the first COVID‐19 vaccine, Sinopharm, being granted for public use, China has been preparing vaccination initiatives and designing the mass vaccination program for the general public.11

However, even with available COVID-19 vaccines, the vaccine rollout remains a huge challenge, and vaccine hesitancy is one of the predominant obstacles.12–18 The past decade has seen vaccine hesitancy becoming a growing global public concern, and its complex determinants, including demography, disease, place, time, and other contextual factors, have made the detection of reasons and design of intervention hard tasks.19–22 For the COVID-19 vaccine, which was developed and approved urgently against a newly emerging infectious disease, the hesitancy may be severer.12–14,23–28 A systematic review found that as the pandemic progressed, the rate of willingness to accept COVID-19 vaccination has decreased.28 Even in countries that have launched vaccination programs or have been relatively well-prepared in the supply side, such as France and Italy, the public refusal or hesitancy to get vaccinated is also a policy concern.13,26,29 Some factors have contributed to the hesitancy, such as socio-economic characteristics (age, gender, etc.), perception toward vaccination, misinformation or conspiracy theory in the social media, etc.23–25,27,28,30–33 To control the pandemic at the national and global level, effective and appropriate prompting interventions, designed based on evidence and studies, are urgently needed.15–17

Although China has relatively contained the pandemic, the large population base and uncertainty of the present public perception for the vaccination have made it difficult to increase the uptake of the future COVID-19 vaccine.34,35 A few studies, mainly conducted during the pandemic period in China, have reported a public intention rate for future COVID-19 vaccination about 83.3%-91.3%.31,36,37 And one study identified a decline in the acceptance from the severe-pandemic period (March 2020) to the well-contained period (Nov-Dec 2020).37 Unlike other countries, China has intended to start the mass vaccination program with healthy adults aged 18–59 instead of vulnerable population groups (e.g., the elderly or those with chronic disease), considering a relatively low risk of pandemic and uncertain safety consequences of the vaccination.11,38 So, understanding adults’ perception would be the priority to assess potential barriers to the vaccination and prepare for the forthcoming national vaccination campaign.30,31,36 The elderly and those with non-communicable chronic diseases (NCDs) should also be investigated, as they have a higher infection risk and severity of the COVID-19 diseases and therefore are the priority groups for vaccination.8,9 Besides, due to the health status or other socio-economic factors, they may have different acceptance or concerns about the COVID-19 vaccination compared with adults or the healthy population.27,28,39,40 Articles in other countries like the US found higher acceptability of the elderly, but there are mixed findings on the effect of NCD on the vaccination intention so far.26–28,39,40 While most of the existing studies in China were conducted online with a limited sample size, it is hard to access different population groups and identify the possible difference of the vaccination perception.30,31,37 In addition, facing an increasing threat of misinformation about COVID-19 vaccination across media outlets and complexity in vaccine hesitancy, researchers worldwide have urged to understand the information sources that individuals trusted or used and to specify the reasons for not accepting a vaccine so that health education by authorities or healthcare workers could reach and impact the population effectively via these sources and address potential vaccine hesitancy.16,17,41–43

As early as December 8, 2020, Britain has started its vaccination campaign, followed by the US on December 14 and Israel on December 19.44 And the vast majority of the European Union launched vaccination drives on December 27.44 China was also among the first countries to commence vaccination programs.11,44 China has launched its first vaccination program targeting several key population groups since December 15, 2020, and intended to expand the program toward the general adult population aged 18–59 in the following 2 months.11 During the well-controlled pandemic and the preparation of a mass vaccination program in China, we conducted a large-scale field survey to assess the public perception of COVID-19 vaccination and the willingness to get vaccinated, with the aim to examine the specific perception in the elderly and the people with NCD. This study would provide the latest evidence of the public willingness to accept the newly developed COVID-19 vaccine and the public perception of vaccination, which informs the design of interventions to increase vaccine uptake.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Study design, population and sampling

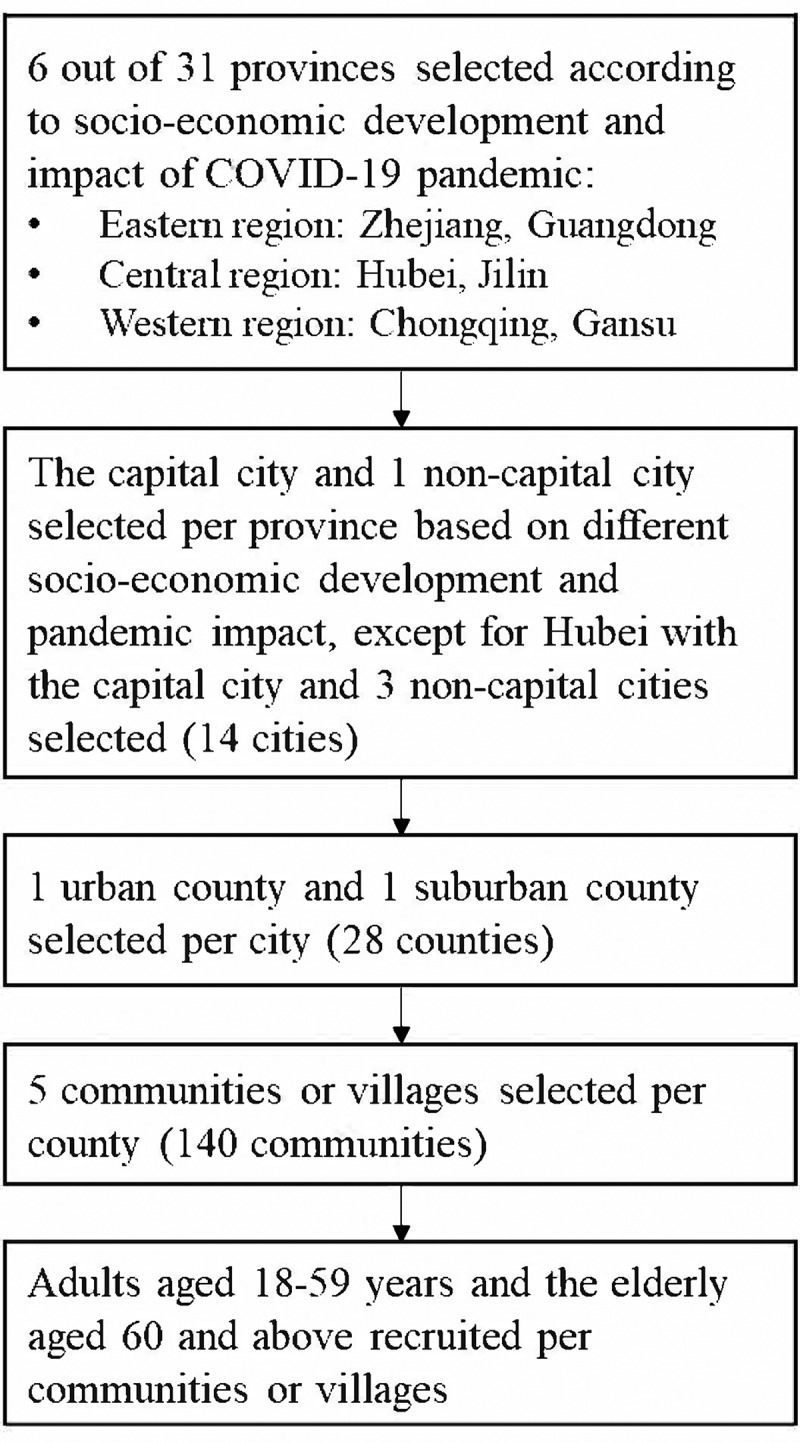

A cross-sectional field survey was conducted among adults in China from November 17, 2020, to January 28, 2021, when the national vaccination program was being prepared. A multistage sampling approach was used, and Figure 1 shows the sampling process in detail. In total, 140 communities or villages of 28 counties in 6 provinces were selected as the sample places surveyed. Investigators were recruited from local community health centers or community resident committees, and trained by central or provincial Centers for Disease Prevention and Control. Eligibility criteria of participants included: being a Chinese resident, aged 18 and above, having no communication difficulties, and consenting to participate in the survey. With the assistance of local health service centers or resident committees in providing suggestions and helping to acquire the locals’ permission, investigators recruited participants by inviting adults on the road and/or conducting household surveys within the community or village. Investigators conducted the face to face interviews with the participants in the local health service centers or resident committees, or in the participants’ household. The questionnaire was filled by the investigators. The average time for each interview was 15 minutes. The study was approved by Peking University Institutional Review Board (IRB00001052-20011).

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the sampling process. In stage two, two cities in each province other than Hubei were selected: the capital city with a relatively higher socio-economic level and higher level of the pandemic, and a non-capital city with a relatively lower socio-economic level and lower level of the pandemic. Four cities in Hubei were selected, the capital city and three non-capital cities, based on the same stratification method of social-economic level and the pandemic scale, because the Hubei was the most severely impacted by the pandemic.

2.2. Measures

Based on studies of the acceptance of vaccines against newly emerging infectious diseases13,14,31,32,45–48 and frameworks of vaccine hesitancy,19,20 the questionnaire was developed to include four sections: (1) Demographic characteristics, including age, gender, health status, NCD status, education, employment status, marital status, annual household income in 2019, region (urban/rural) and province. (2) Perception of COVID-19 vaccination and vaccine, including the perceived infection risk and severity of COVID-19, the importance of vaccination, perceived safety and effectiveness of the COVID-19 vaccine, and trust in health workers and governments regarding vaccination information and suggestions. A 5-point Likert scale (e.g., “very high” to “very low” on infection risk and severity, “very important” to “very unimportant” on vaccination importance) was used to assess each item mentioned above, except for the measure of perceived safety and effectiveness of the vaccine using a 3-point scale. The perceptions for the COVID-19 diseases and the vaccination, which surveyed each aspects of the concept framework of vaccine hesitancy, are the potential impact factors on the individuals’ decision-making of vaccination.20 (3) Willingness to accept the future COVID-19 vaccination and reasons for vaccine hesitancy. The primary outcome of the survey was the willingness to accept COVID-19 vaccination using the question “When the COVID-19 vaccine is available for the public, would you be willing to get the vaccination?.” Respondents who answered “Unsure” or “No” were asked to answer reasons for vaccine hesitancy in a multiple-choice question consisted of designed reasons and an open-end choice to report other reasons not listed. The reasons were designed based on the “3 C” vaccine hesitancy model proposed by the World Health Organization (WHO) Strategic Advisory Group of Experts (SAGE) Working Group, which measures the participants’ confidence (e.g., the effectiveness and safety of vaccines), complacency (e.g., perceived risks and severity of the disease) and convenience (e.g., affordability, geographical accessibility) for vaccination.20 In addition, the nfluence of newly developed vaccines on the perception of vaccination, which has been reported by studies of H1N1 influenza and the present COVID-19, were considered, such as the reason “waiting and seeing others getting vaccinated.”14,31,46,47 (4) Information sources for COVID-19 vaccines and vaccination, including the’ sources frequently used (by the multiple-choice question) and the source from which respondents were most likely to accept vaccination recommendations. The content validity is tested to cover aspects of vaccination hesitancy and perception proposed by the SAGE groups. The experts of China Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention examined the questionnaire in Chinese to ensure its readability, clarity and comprehensiveness for Chinese population (Supplemental Materials 1).

2.3. Statistical analysis

EpiData 3.1 (EpiData Association, Odense, Denmark) was used to input survey data, and the statistical analyses were performed in Stata 16.0 (Stata Corp, College Station, TX, USA). Descriptive statistics were used to describe respondents’ demographic characteristics, perception of COVID-19 vaccination and vaccine, and information sources. Chi-squared tests were used to examine differences in vaccination intention, perception on vaccination and vaccine, reasons for vaccine hesitancy, and information sources among respondents between two age groups (adults aged 18–59 and the elderly) and between respondents with and without NCD in two age groups, respectively. Categorical measures of vaccination perception with 5-point Likert scales, including the perceived infection risk and severity of COVID-19, vaccination importance, trust in health workers and governments, were merged as binary scales for analysis. Answers of the two scales “very high/important” and “high/important” were merged as one category, and another three scales “fair,” “low/unimportant” and “very low/unimportant” were merged as the other category. Multiple logistic regressions were conducted in the total sample and then in two age groups, respectively, to identify associated factors of COVID-19 vaccination intention, including the demographic characteristics and perceptions for the vaccination. Adjusted odds ratio (aOR), 95% confidence interval (CI), and p-value were presented.

3. Results

3.1. Respondent characteristics

A total of 7259 participants were recruited. Among them, 3928 were adults aged 18–59, and 3331 were elderly aged 60 and above. Table 1 presented the demographic characteristics of the respondents. The average age was 38.79 years old (standard deviation = 11.21) in adults aged 18–59 and 68.85 years old (standard deviation = 6.25) in the elderly. The self-reported health status score of the elderly (73.97) was lower than that of the adults aged 18–59 (85.06). And the proportion of having noninfectious chronic diseases (non-NCD) was 55.96% in the elderly and 13.06% in adults aged 18–59. 41.29% of adults aged 18–59 and 48.90% of the elderly were male. 46.87% of adults aged 18–59 had a degree of associate/ bachelor and above, and 55.00% of the elderly had a degree of primary school and below. The employment rate was 76.63% in adults aged 18–59 and 28.37% in the elderly, and the marriage rate was at the same level (81.77% and 82.62%). 63.59% of the adults aged 18–59 and 51.70% of the elderly lived in urban. The family income level in the elderly was lower compared with that of adults aged 18–59, as 79.14% of the elderly had an annual household income below CNY 100,000 in 2019.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics

| Characteristics | Adults aged 18–59 (n = 3928) |

The elderly aged 60 and above (n = 3331) |

Total sample (n = 7259) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean(SD) | 38.79 (11.21) | 68.85 (6.25) | 52.59 (17.61) |

| Having NCD, n(%) | 513 (13.06) | 1864 (55.96) | 2377 (32.75) |

| Health status score, mean(SD) | 85.06 (11.93) | 73.97 (15.04) | 79.97 (14.53) |

| Male, n(%) | 1622 (41.29) | 1629 (48.90) | 3308 (45.57) |

| Education, n(%) | |||

| Primary school and below | 414 (10.54) | 1832 (55.00) | 2246 (30.94) |

| Middle or high school | 763 (19.42) | 752 (22.58) | 1515 (20.87) |

| Senior high school | 910 (23.17) | 532 (15.97) | 1442 (19.86) |

| Associate/bachelor and above | 1841 (46.87) | 215 (6.45) | 2056 (28.32) |

| Employed, n(%) | 3010 (76.63) | 945 (28.37) | 3955 (54.48) |

| Married, n(%) | 3212 (81.77) | 2752 (82.62) | 5964 (82.16) |

| Annual household income in 2019, n(%) | |||

| ≤ CNY 50,000 | 1225 (31.19) | 1699 (51.01) | 2924 (40.28) |

| CNY 50,000–100,000 | 1406 (35.79) | 937 (28.13) | 2343 (32.28) |

| CNY 100,000–150,000 | 669 (17.03) | 424 (12.73) | 1093 (15.06) |

| ≥CNY 150,000 | 628 (15.99) | 271 (8.14) | 899 (12.38) |

| Urban, n(%) | 2498 (63.59) | 1722 (51.70) | 4220 (58.13) |

| Province, n(%) | |||

| Jilin | 572 (14.56) | 433 (13.00) | 1005 (13.84) |

| Guangdong | 575 (14.64) | 414 (12.43) | 989 (13.62) |

| Zhejiang | 521 (13.26) | 486 (14.59) | 1007 (13.87) |

| Hubei | 1037 (26.40) | 963 (28.91) | 2000 (27.55) |

| Gansu | 698 (17.77) | 582 (17.47) | 1280 (17.63) |

| Chongqing | 525 (13.37) | 453 (13.6) | 978 (13.47) |

3.2. Willingness to accept the COVID-19 vaccination and related perception

Table 2 compares the willingness to accept COVID-19 vaccination and related perception among respondents by age and NCD status. The intention rate for COVID‐19 vaccination in adults aged 18–59 was 84.75% (95% CI = 83.63–85.87), which was higher than that of the elderly (79.08%, 95% C = 77.70–80.46) by the univariate test (p < .001). Vaccine hesitancy was found in both groups, with 15.25% (95% CI = 14.13–16.37) of adults aged 18–59 and 20.92% (95% CI = 19.54–22.30) of the elderly being unsure or unwilling to get the vaccination. More proportion of adults aged 18–59 perceived high COVID-19 infection risk (30.50%, 95% CI = 29.06–31.94) or high severity of COVID-19 diseases (83.50%, 95% CI = 82.34–84.66), compared with the elderly (23.78%, 95% CI = 22.33–25.23, and 79.74%, 95% CI = 78.38–81.10, respectively) (p < .001). And the proportions of participants who believed the vaccination is important to themselves (86.05%, 95% CI = 84.97–87.13) or others (87.63%, 95% CI = 86.60–88.66) were also higher in adults aged 18–59 than in the elderly (79.41%, 95% CI = 78.04–80.78 and 81.15%, 95% CI = 79.82–82.48, respectively) (p < .001). Regarding the vaccine confidence, though 65.05% (95% CI = 63.56–66.54) of adults aged 18–59 and 63.58% (95% CI = 61.95–65.21) of the elderly believed in the safety when it was approved and available for the public, there is still about 30% in both groups being unsure. And the adults aged 18–59 showed more confidence in the effectiveness (68.30%, 95% CI = 66.84–69.76) than the elderly (65.51%, 95% CI = 63.90–67.12) (p = .036). Besides, the elderly was found to have lower trust in health workers (84.93%, 95% CI = 83.72–86.14) or governments (85.05%, 95% CI = 83.84–86.26) compared with adults aged 18–59 (90.17%, 95% CI = 89.24–91.10 and 89.59%, 95% CI = 88.63–90.55, respectively) (p < .001).

Table 2.

Comparison of COVID-19 vaccination intention and perception among respondents with different age and NCD status, (%, 95% CI)

| Items | Adults aged 18–59 |

The elderly aged 60 and above |

p-valuea | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total sample (n = 3928) |

NCD status |

Total sample (n = 3331) |

NCD status |

||||||

| No (n = 3415) |

Yes (n = 513) |

p-valueb | No (n = 1467) |

Yes (n = 1864) |

p-valueb | ||||

| COVID-19 vaccination intention | 0.001 | 0.44 | <0.001 | ||||||

| Yes | 84.75 (83.63, 85.87) | 85.48 (84.30, 86.66) | 79.92 (76.45, 83.39) | 79.08 (77.70, 80.46) | 79.69 (77.63, 81.75) | 78.59 (76.73, 80.45) | |||

| Unsure or no | 15.25 (14.13, 16.37) | 14.52 (13.34, 15.70) | 20.08 (16.61, 23.55) | 20.92 (19.54, 22.30) | 20.31 (18.25, 22.37) | 21.41 (19.55, 23.27) | |||

| Complacency measures | |||||||||

| Perceived risk of COVID-19 infection | 0.16 | 0.034 | <0.001 | ||||||

| High | 30.50 (29.06, 31.94) | 30.89 (29.34, 32.44) | 27.88 (24.00, 31.76) | 23.78 (22.33, 25.23) | 22.02 (19.90, 24.14) | 25.16 (23.19, 27.13) | |||

| Fair or low | 69.50 (68.06, 70.94) | 69.11 (67.56, 70.66) | 72.12 (68.24, 76.00) | 76.22 (74.77, 77.67) | 77.98 (75.86, 80.10) | 74.84 (72.87, 76.81) | |||

| Perceived severity of COVID-19 diseases | 0.76 | 0.172 | <0.001 | ||||||

| High | 83.50 (82.34, 84.66) | 83.57 (82.33, 84.81) | 83.04 (79.79, 86.29) | 79.74 (78.38, 81.10) | 21.34 (19.24, 23.44) | 19.42 (17.62, 21.22) | |||

| Fair or low | 16.50 (15.34, 17.66) | 16.43 (15.19, 17.67) | 16.96 (13.71, 20.21) | 20.26 (18.9, 21.62) | 78.66 (76.56, 80.76) | 80.58 (78.78, 82.38) | |||

| Importance of COVID-19 vaccination for myself | 0.008 | 0.382 | <0.001 | ||||||

| Important | 86.05 (84.97, 87.13) | 86.62 (85.48, 87.76) | 82.26 (78.95, 85.57) | 79.41 (78.04, 80.78) | 80.10 (78.06, 82.14) | 78.86 (77.01, 80.71) | |||

| Fair or not important | 13.95 (12.87, 15.03) | 13.38 (12.24, 14.52) | 17.74 (14.43, 21.05) | 20.59 (19.22, 21.96) | 19.90 (17.86, 21.94) | 21.14 (19.29, 22.99) | |||

| Importance of COVID-19 vaccination for others (e.g. family, friends, neighbors) | 0.001 | 0.044 | <0.001 | ||||||

| Important | 87.63 (86.60, 88.66) | 88.29 (87.21, 89.37) | 83.24 (80.01, 86.47) | 81.15 (79.82, 82.48) | 82.69 (80.75, 84.63) | 79.94 (78.12, 81.76) | |||

| Fair or not important | 12.37 (11.34, 13.40) | 11.71 (10.63, 12.79) | 16.76 (13.53, 19.99) | 18.85 (17.52, 20.18) | 17.31 (15.37, 19.25) | 20.06 (18.24, 21.88) | |||

| Confidence measures | |||||||||

| Perceived safety of COVID-19 vaccines | 0.194 | 0.47 | 0.058 | ||||||

| Safe | 65.05 (63.56, 66.54) | 65.56 (63.97, 67.15) | 61.60 (57.39, 65.81) | 63.58 (61.95, 65.21) | 62.44 (59.96, 64.92) | 64.48 (62.31, 66.65) | |||

| Unsure | 31.01 (29.56, 32.46) | 30.60 (29.05, 32.15) | 33.72 (29.63, 37.81) | 33.17 (31.57, 34.77) | 34.22 (31.79, 36.65) | 32.35 (30.23, 34.47) | |||

| Not safe | 3.95 (3.34, 4.56) | 3.84 (3.20, 4.48) | 4.68 (2.85, 6.51) | 3.24 (2.64, 3.84) | 3.34 (2.42, 4.26) | 3.17 (2.37, 3.97) | |||

| Perceived effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines | 0.72 | 0.263 | 0.036 | ||||||

| Effective | 68.30 (66.84, 69.76) | 68.43 (66.87, 69.99) | 67.45 (63.40, 71.50) | 65.51 (63.90, 67.12) | 64.01 (61.55, 66.47) | 66.68 (64.54, 68.82) | |||

| Unsure | 29.43 (28.00, 30.86) | 29.37 (27.84, 30.90) | 29.82 (25.86, 33.78) | 32.21 (30.62, 33.80) | 33.54 (31.12, 35.96) | 31.17 (29.07, 33.27) | |||

| Not effective | 2.27 (1.80, 2.74) | 2.20 (1.71, 2.69) | 2.73 (1.32, 4.14) | 2.28 (1.77, 2.79) | 2.45 (1.66, 3.24) | 2.15 (1.49, 2.81) | |||

| Trust in health workers regarding vaccination information and suggestions | <0.001 | 0.28 | <0.001 | ||||||

| Trust | 90.17 (89.24, 91.10) | 91.04 (90.08, 92.00) | 84.41 (81.27, 87.55) | 84.93 (83.72, 86.14) | 85.69 (83.90, 87.48) | 84.33 (82.68, 85.98) | |||

| Fair or not trust | 9.83 (8.90, 10.76) | 8.96 (8.00, 9.92) | 15.59 (12.45, 18.73) | 15.07 (13.86, 16.28) | 14.31 (12.52, 16.10) | 15.67 (14.02, 17.32) | |||

| Trust in governments regarding vaccination information and suggestions | 0.004 | 0.82 | <0.001 | ||||||

| Trust | 89.59 (88.63, 90.55) | 90.13 (89.13, 91.13) | 85.96 (82.95, 88.97) | 85.05 (83.84, 86.26) | 85.21 (83.39, 87.03) | 84.92 (83.3, 86.54) | |||

| Fair or not trust | 10.41 (9.45, 11.37) | 9.87 (8.87, 10.87) | 14.04 (11.03, 17.05) | 14.95 (13.74, 16.16) | 14.79 (12.97, 16.61) | 15.08 (13.46, 16.7) | |||

aComparison of the difference between two age groups on COVID-19 vaccination intention and perception measures by Chi-square tests.

bComparison of the difference between respondents with or without NCD on vaccination intention and perception measures in two age groups, respectively, by Chi-square tests.

In adults aged 18–59, the univariate analysis found the willingness to get vaccinated was lower in respondents with NCD (79.92%, 95% CI = 76.45–83.39) than that of those without NCD (85.48%, 95% CI = 84.30–86.66)) (p = .001), but no significant difference was found between the elderly with and without NCDs. In both age groups, those with NCDs shows a lower proportion in believing in the vaccination importance for others. And no significant relationships were found between NCD status and the confidence in COVID-19 vaccine safety and effectiveness in both age groups.

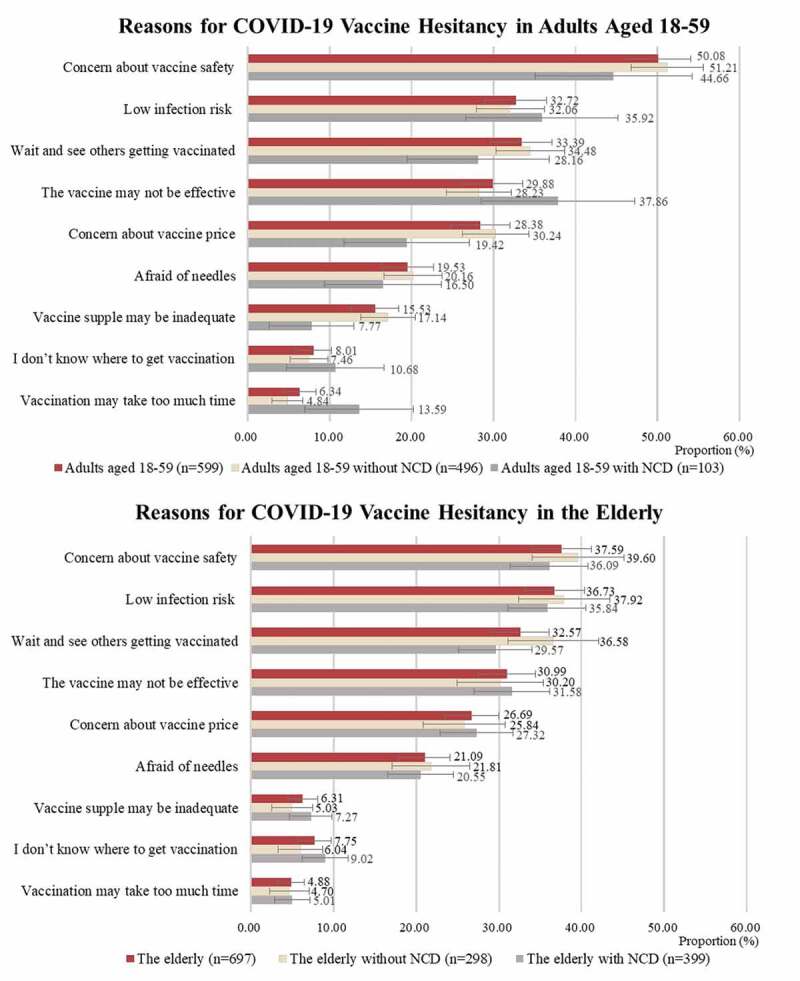

3.3. Reasons for COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy

Figure 2 presents the main reasons (reported proportion>10%) for COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy by age and NCD status of the participants. In both groups, the top 5 reasons are concern about vaccine safety, low infection risk, waiting and seeing others getting vaccinated, concern about vaccine effectiveness and price. But the relative importance of reasons differed. In respondents aged 18–59, the most important reason was concern about vaccine safety (50.08%, 95% CI = 46.08–54.09), followed by low infection risk (32.72%, 95% CI = 28.96–36.48) and waiting and seeing (33.39%, 95% CI = 29.61–37.17). In the elderly, the concern of vaccine safety (37.59%, 95% CI = 33.99–41.19) and low infection risk (36.73%, 95% CI = 33.15–40.31) ranked as the two most frequently reported reasons. And statistical tests show that the adult participants aged 18–59 were significantly more concerned about the vaccine safety (50.08%, 95% CI = 46.08–54.09 vs 37.59%, 95% CI = 33.99–41.19) and adequacy of vaccine supply (15.53%, 95% CI = 12.63–18.43 vs 6.31, 95% CI = 4.51–8.12%) compared with the elderly (p < .05). Regarding the reason for vaccine hesitancy between respondents with and without NCDs, significant differences were found among the adults aged 18–59. Those without NCDs were more like to be hesitant because of concern about vaccine price (30.2%, 95% CI = 26.20–34.28 vs 19.4%, 95% CI = 11.78–34.28), adequacy of supply (17.14%, 95% CI = 13.82–20.45 vs 7.77%, 95% CI = 2.60–12.94) compared with those with NCDs (p < .05), while the NCD population were more concerned that the vaccination may take too much time (13.59, 95% CI = 6.97–20.21 vs 4.84%, 95% CI = 2.95–6.73) (p < .05). In the elderly, no significant differences were found, though more of the healthy elderly intended to wait and see others getting vaccinated (36.58%, 95% CI = 31.11–42.05 vs 29.57%, 95% CI = 25.10–34.05, p = .051).

Figure 2.

Reasons for COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in adults aged 18–59 and the elderly. Chi-square tests were used to examine differences in the proportion of each reason between participant groups by ages and NCD status. Between the adults aged 18–59 and the elderly, the proportions of reasons that have significant differences are “concern about vaccine safety” and “vaccine supply may be inadequate” are (p < .05). Between the adults aged 18–59 with and without NCD, the proportions of reasons that have significant differences are “concern about vaccine price,” “vaccine supply may be inadequate” and “vaccination may take too much time” (p < .05). The p-value of the chi-square test in the proportion of “the vaccine may not be effective” is 0.052. Between the elderly with and without NCD, no significant differences are found among the reasons. The p-value of the chi-square test in the proportion of “wait and see others getting vaccinated” is 0.051.

3.4. Influencing factors of willingness to accept COVID-19 vaccination

Appendix Table A1 shows the association of demographic characteristics with the willingness to accept the future COVID-19 vaccine in the total sample. Age, measured as the continuous variable, was identified as a significant impact factor, and older respondents were less likely to accept the vaccine (aOR = 0.994, 95% CI = 0.989–0.999). But the influence of NCD was not significant (aOR = 0.979, p = .79). And as shown in Appendix Table A2, univariate analyses show that perception for vaccination, including the vaccine complacency and confidence, are significantly associated with the willingness to accept the COVID-19 vaccine in both age groups. In Table 3, multiple logistic regressions were conducted in the adults aged 18–59 and the elderly participants, respectively, to identify the influencing factors, controlling for demographic characteristics. In both age groups, those who believed in COVID-19 vaccination importance for themselves (adults aged 18–59: aOR = 3.16, 95% CI = 2.12–4.72; the elderly: aOR = 2.61, 95% CI = 1.78–3.83) and for others (adults aged 18–59: aOR = 1.77, 95% CI = 1.16–2.68; the elderly: aOR = 1.86, 95% CI = 1.26–2.74) were more likely to accept the vaccine. And those who believed in vaccine safety (adults aged 18–59: aOR = 2.15, 95% CI = 1.60–2.90; the elderly: aOR = 1.58, 95% CI = 1.12–2.22) and effectiveness (adults aged 18–59: aOR = 2.91, 95% CI = 2.15–3.93; the elderly: aOR = 2.99, 95% CI = 2.13–4.20) were also more likely to accept the vaccine compared with those do not. And those who trusted in health workers regarding vaccination information and suggestions more intended to get the vaccination (adults aged 18–59: aOR = 2.02, 95% CI = 1.38–2.97; the elderly: aOR = 1.52, 95% CI = 1.07–2.16). Some other factors were found to be significantly associated with the vaccination intention in the elderly group. The elderly who perceived high infection risk were more likely to accept a vaccine than those who did not (aOR = 1.70, 95% CI = 1.26–2.30). Those who trusted in governments regarding vaccination information and suggestions were more likely to accept the vaccine (aOR = 2.31, 95% CI = 1.62–3.28).

Table 3.

Influence factors of willingness to accept COVID-19 vaccine by multiple logistic regressions

| Variables | Adults aged 18–59 |

The elderly |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| aOR (95% CI) | p-value | aOR (95% CI) | p-value | |

| Perceived high infection risk (yes vs. no) | 1.04 (0.81–1.32) | 0.78 | 1.70 (1.26–2.30) | 0.001 |

| Perceived high severity of COVID-19 diseases (yes vs. no) | 1.25 (0.95–1.65) | 0.11 | 0.94 (0.72–1.23) | 0.66 |

| Believe COVID-19 vaccination is important for myself (yes vs. no) | 3.16 (2.12–4.72) | <0.001 | 2.61 (1.78–3.83) | <0.001 |

| Believe COVID-19 vaccination is important for others (yes vs. no) | 1.77 (1.16–2.68) | 0.008 | 1.86 (1.26–2.74) | 0.002 |

| Believe the COVID-19 vaccine is safe (yes vs. no) | 2.15 (1.60–2.90) | <0.001 | 1.58 (1.12–2.22) | 0.01 |

| Believe the COVID-19 vaccine is effective (yes vs. no) | 2.91 (2.15–3.93) | <0.001 | 2.99 (2.13–4.20) | <0.001 |

| Trust in health workers regarding vaccination information and suggestions (yes vs. no) | 2.02 (1.38–2.97) | <0.001 | 1.52 (1.07–2.16) | 0.02 |

| Trust in governments regarding vaccination information and suggestions (yes vs. no) | 1.34 (0.91–1.98) | 0.143 | 2.31 (1.62–3.28) | <0.001 |

| Age | 0.99 (0.98–1.01) | 0.37 | 1.00 (0.97–1.01) | 0.25 |

| Have NCD (yes vs. no) | 0.85 (0.61–1.17) | 0.32 | 1.04 (0.83–1.31) | 0.73 |

| Health status | 0.99 (0.98–1.00) | 0.15 | 1.00 (0.99–1.01) | 0.52 |

| Male (vs. female) | 1.09 (0.88–1.36) | 0.44 | 1.24 (1.00–1.54) | 0.05 |

| Education (vs. primary school and below) | ||||

| Middle or high school | 1.27 (0.85–1.88) | 0.24 | 1.14 (0.86–1.52) | 0.35 |

| Senior high school | 1.21 (0.83–1.77) | 0.33 | 1.04 (0.76–1.43) | 0.81 |

| Associate/bachelor and above | 0.92 (0.62–1.37) | 0.69 | 0.88 (0.57–1.35) | 0.55 |

| Married (vs. single/divorced/widowed) | 0.86 (0.61–1.20) | 0.37 | 1.07 (0.80–1.43) | 0.67 |

| Employed (vs. unemployed) | 1.23 (0.96–1.58) | 0.11 | 1.33 (1.02–1.72) | 0.03 |

| Annual household income in 2019 (vs. ≤ CNY 50,000) | ||||

| CNY 50,000–100,000 | 0.89 (0.69–1.15) | 0.38 | 1.12 (0.86–1.46) | 0.41 |

| CNY 100,000–150,000 | 1.27 (0.88–1.84) | 0.20 | 0.84 (0.59–1.20) | 0.34 |

| ≥CNY 150,000 | 0.82 (0.56–1.20) | 0.30 | 0.63 (0.42–0.94) | 0.02 |

| Urban (vs. rural) | 1.08 (0.85–1.37) | 0.53 | 0.82 (0.64–1.05) | 0.11 |

| Province (vs. Jilin) | ||||

| Guangdong | 1.17 (0.79–1.72) | 0.43 | 1.44 (0.96–2.17) | 0.08 |

| Zhejiang | 1.04 (0.68–1.58) | 0.87 | 0.76 (0.50–1.16) | 0.20 |

| Hubei | 2.62 (1.84–3.73) | <0.001 | 2.78 (1.95–3.98) | <0.001 |

| Gansu | 0.41 (0.29–0.58) | <0.001 | 0.36 (0.25–0.54) | <0.001 |

| Chongqing | 2.99 (1.89–4.73) | <0.001 | 2.53 (1.59–4.04) | <0.001 |

Respondents who had vaccine hesitancy (reported “unsure” or “no” for the vaccination) as reference group.

3.5. Information sources for COVID-19 vaccines and vaccination

Table 4 presents the information sources for COVID-19 vaccines and vaccination among respondents of different ages and NCD statuses. In adult respondents aged 18–59, television and/or radio (85.23%, 95% CI = 84.12–86.34), social media (76.88%, 95% CI = 75.57–78.20) and network platform (64.84%, 95% CI = 63.35–66.34) were three major sources. In the elderly, family, relatives, friends (57.85%, 95% CI = 56.17–59.53) were also the frequently used sources except for television and/or radio (86.2%, 95% CI = 85.05–87.39), and they used social media (40.44%, 95% CI = 38.77–42.10) and network platform (29.3%, 95% CI = 27.75–30.85) less. The sources providing official information in China included official government website and platform, and medical professional platform or healthcare personnel. And fewer of the elderly reported using the two official sources compared with the respondents aged 18–59 (36.03%, 95% CI = 34.39–37.66 vs 57.20%, 95% CI = 55.66–58.75 for official government website and platform, 39.24, 95% CI = 37.58–40.90 vs 52.85%, 95% CI = 51.29–54.41 for medical professional platform or healthcare personnel).

Table 4.

Information sources for COVID-19 vaccines and vaccination among respondents with different age and NCD status, (%, 95% CI)

| Items | Adults aged 18–59 (n = 3928) |

The elderly aged 60 and above (n = 3331) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total sample (n = 3928) |

NCD status |

Total sample (n = 3331) |

NCD status |

|||

| No (n = 3415) | Yes (n = 513) | No (n = 1467) | Yes (n = 1864) | |||

| Information sources for COVID-19 vaccines and vaccination | ||||||

| Television and/or radio | 85.23 (84.12, 86.34) | 85.10 (83.94, 86.29) | 86.16 (83.17, 89.15) | 86.22 (85.05, 87.39) | 87.39 (85.69, 89.09) | 85.30 (83.69, 86.91) |

| Newspapers, magazines, books and periodicals | 40.27 (38.74, 41.81) | 40.64 (38.99, 42.29) | 37.82 (33.62, 42.01) | 26.93 (25.42, 28.44) | 30.20 (27.85, 32.55) | 24.36 (22.41, 26.30) |

| Social media (e.g. Weixin, Weibo, Toutiao, short-form video) | 76.88 (75.57, 78.20) | 77.98 (76.62, 79.37) | 69.59 (65.61, 73.57) | 40.44 (38.77, 42.10) | 45.47 (42.92, 48.02) | 36.48 (34.30, 38.67) |

| Network platform (e.g. portal website, search engine, news client APP) | 64.84 (63.35, 66.34) | 66.62 (65.06, 68.20) | 53.02 (48.7, 57.34) | 29.30 (27.75, 30.85) | 32.92 (30.52, 35.33) | 26.45 (24.45, 28.45) |

| Official government website and platform | 57.20 (55.66, 58.75) | 58.33 (56.69, 59.98) | 49.71 (45.38, 54.03) | 36.03 (34.39, 37.66) | 37.56 (35.08, 40.04) | 34.82 (32.65, 36.98) |

| Medical professional platform or healthcare personnel | 52.85 (51.29, 54.41) | 53.73 (52.07, 55.41) | 46.98 (42.66, 51.30) | 39.24 (37.58, 40.90) | 41.79 (39.26, 44.31) | 37.23 (35.04, 39.43) |

| Family, relatives, and friends | 45.06 (43.51, 46.62) | 44.74 (43.07, 46.41) | 47.17 (42.85, 51.49) | 57.85 (56.17, 59.53) | 59.99 (57.48, 62.49) | 56.17 (53.92, 58.42) |

| Others | 0.79 (0.51, 1.07) | 0.79 (0.44, 1.09) | 0.78 (0.02, 1.54) | 1.41 (1.01, 1.81) | 1.91 (1.21, 2.61) | 1.02 (0.56, 1.48) |

| Most trusted information source in receiving vaccination recommendationsa, b, c | ||||||

| Television and/or radio | 18.30 (17.10, 19.51) | 17.95 (16.63, 19.24) | 20.66 (17.16, 24.17) | 26.84 (25.33, 28.34) | 28.56 (26.25, 30.87) | 25.48 (23.50, 27.46) |

| Newspapers, magazines, books and periodicals | 1.48 (1.10, 1.85) | 1.61 (1.14, 2.03) | 0.58 (0, 1.24) | 0.90 (0.58, 1.22) | 0.82 (0.36, 1.28) | 0.97 (0.52, 1.41) |

| Social media (e.g. Weixin, Weibo, Toutiao, short-form video) | 6.98 (6.18, 7.77) | 7.12 (6.21, 7.98) | 6.04 (3.98, 8.1) | 3.36 (2.75, 3.97) | 3.95 (2.96, 4.95) | 2.90 (2.14, 3.66) |

| Network platform (e.g. portal website, search engine, news client APP) | 2.95 (2.42, 3.48) | 2.90 (2.29, 3.46) | 3.31 (1.76, 4.86) | 1.62 (1.19, 2.05) | 1.70 (1.04, 2.37) | 1.56 (0.99, 2.12) |

| Official government website and platform | 33.32 (31.85, 34.80) | 33.56 (31.96, 35.14) | 31.77 (27.74, 35.80) | 26.18 (24.69, 27.67) | 25.56 (23.33, 27.79) | 26.66 (24.66, 28.67) |

| Medical professional platform or healthcare personnel | 33.53 (32.05, 35.00) | 33.70 (32.10, 35.29) | 32.36 (28.31, 36.41) | 29.72 (28.17, 31.27) | 29.58 (27.25, 31.92) | 29.83 (27.75, 31.91) |

| Family, relatives, and friends | 2.70 (2.19, 3.21) | 2.43 (1.86, 2.95) | 4.48 (2.69, 6.27) | 10.75 (9.70, 11.8) | 9.13 (7.66, 10.61) | 12.02 (10.54, 13.49) |

| Others or missing | 0.74 (0.47, 1.01) | 0.73 (0.40, 1.02) | 0.78 (0.02, 1.54) | 0.63 (0.36, 0.90) | 0.68 (0.26, 1.10) | 0.59 (0.24, 0.94) |

aIn adults aged 18–59, difference between respondents with and without NCD were not statistically significant (p = 0.083).

bIn the elderly, difference between respondents with and without NCD were not statistically significant (p = 0.073).

cDifference between respondents of adults aged 18–59 and the elderly were statistically significant (p < 0.001).

Regarding the most trusted information source in receiving vaccination recommendations, medical professional platform or healthcare personnel (33.53%, 95% CI = 32.05–35.00 and 29.72%, 95% CI = 28.17–31.27), official government website and platform (33.32%, 95% CI = 31.85–34.80 and 26.18%, 95% CI = 24.69–27.67) and television and/or radio (18.30%, 95% CI = 17.10–19.51 and 26.84%, 95% CI = 25.33–28.34) were the three most reported sources in respondents aged 18–59 and the elderly. There are significant differences in the most trusted information sources between adult respondents aged 18–59 and the elderly (p < .001). No significant relationship was found between NCD status and the information sources for COVID-19 vaccines and vaccination in both respondents aged 18–59 (p = .083) and the elderly (p = .073).

4. Discussion

In the preparation stage of a national COVID-19 vaccination program in China, the willingness of the elderly to accept COVID‐19 vaccination (79.08%) was lower than adults aged 18–59 (84.75%). No significant difference was found between respondents with and without NCDs, controlled for other demographic characteristics. Compared with the elderly, adults aged 18–59 perceived higher infection risk and severity of COVID-19 diseases. Moreover, they had more recognition of the vaccination importance, confidence in the vaccine effectiveness, and trust in health workers and governments. Concern about vaccine safety, low infection risk, waiting and seeing others getting vaccinated, and concern of the vaccine effectiveness and price were the primary reasons for vaccine hesitancy, which differed in the relative importance between the two age groups and between participants who aged 18–59 with and without NCDs. Besides, the effect of vaccination perception on the willingness to accept the COVID-19 vaccination and the information sources for the vaccination also differed between the two age groups.

A few studies of the COVID-19 vaccination acceptance rate in China have reported rates ranging from 82.3% to 91.3%, which were based on online surveys during the severe-pandemic period.31,36,37,49 The willingness rate of the Chinese public to accept COVID-19 vaccination in our findings was relatively lower than those of previous surveys during the severe-pandemic period, which may be due to our field survey design and survey period (the well-controlled period).31,36,37 However, the intention rate in China was still at a high level compared with other countries, such as about 62% – 80% in European countries, 69% in the UK, and about 50% in the US, and Asian countries had relatively higher intention rates, such as 79.8% in South Korea, 67.0%–93.3% in Indonesia and 94.3% in Malaysia.12,13,24–27,40,48

Socio-economic characteristics, especially age, have been reported to impact the COVID-19 vaccine acceptance.12,23–28,33,40 Our study indicates that the elderly have less willingness to accept COVID‐19 vaccination compared to those aged 18–59. Some previous studies show different results: in some countries and regions, the elderly had a higher level of vaccination willingness compared to the younger, whereas others found a contrary result with a higher level of willingness in the non-elderly.23,26,48,50–54 The different results may be attributed to the different epidemic phases, perceived risk, perceptions for the vaccination, and sociodemographic factors of the participants. Chinese working-aged people were more likely to inoculate themselves compared to the elderly.55 It’s partly because the elderly and the younger in other countries may be under the same possibility to the risk and the elderly can be more sensitive to the risk. But in China, under a well-controlled phase of pandemic, the elderly were less exposed to the infection risk and up-to-date information, and thus it was hard to raise their awareness for the vaccination. Furthermore, the relationship between NCD status and willingness to accept the COVID-19 vaccination has not been conclusive.26,28,33,37 A higher proportion of Chinese adults in Beijing with chronic diseases were found to be willing to get vaccinated compared to those without the diseases.56 We found no significant difference in the willingness of NCD patients compared with that of the non-NCD population in the multiple analysis, which may be due to the control of the health status.

However, experiences of the vaccination against newly infectious diseases, such as H1N1 influenza, have suggested that a high acceptance would not guarantee a real uptake, and many impact factors should be considered to promote the vaccine coverage, including public perception about the disease, confidence of vaccine profiles, and vaccination convenience, etc.24,26,45,46 We found that the perception of the COVID-19 vaccination importance (for oneself and others) and vaccine confidence (safety and effectiveness) were strong predictors of the willingness to be vaccinated, which were consistent with previous studies.37,48 Nonetheless, the perceived severity of COVID-19 disease did not significantly enhance their willingness in Chinese respondents.30,37 Meanwhile, the difference of some impact factors that we found between the adults aged 18–59 and those aged 60 and above may also help to explain the aforementioned difference of willingness between the subgroups. The elderly generally have a lower education level, income level, and employment rate compared with adults aged 18–59, which may reduce their infection risk and contribute to their perceptions on lower infection risk and severity, the less awareness and confidence on the vaccine and less trust in health authorities. These perceptions have been suggested to be important determinants of vaccination decision.19,27,31,48 As the elderly consist of a large part of the general population in China and are the key population in the COVID-19 vaccination campaign, more resources and specific-designed interventions, especially health education and promotion, need to be deployed to motivate them.

For respondents with vaccine hesitancy, the concern of vaccine safety was the primary reason, which was reported by 50.1% of the adults aged 18–59 and 37.6% of the elderly.13,14,25,33,48 And only about 60% of the respondents in both age groups believed that the vaccine would be safe when it was approved and available, with 30% being unsure. More importantly, the widely-reported reasons “low infection risk” (>30%) and “waiting and seeing others getting vaccinated” (>30%) suggest a dilemma for COVID-19 vaccination in China and other countries/regions that have contained the pandemic: the better control of the disease, the slower the vaccine rollout.57 So, to encourage the public to accept the vaccination rapidly, more efforts are needed in addressing related vaccination barriers, such as reducing possible adverse reactions in vaccine development, promoting the access, convenience, and affordability for immunization, alleviating the public’s wait-and-see attitude by health education.6,15,17,18,31,42,43 Besides, in adult participants aged 18–59, the relative importance of reasons for vaccine hesitancy differed between those with and without NCDs: the NCD patients’ decision on vaccination was more influenced by infection risk, vaccine effectiveness, and vaccination convenience (e.g., time, place), which suggests for targeted promotion strategies for NCD patients aged 18–59.

To address vaccine hesitancy and promote perception for COVID-19 vaccine and vaccination, conducting better communication via appropriate channels toward the public are urgently needed.16,17,41–43 This is especially important under the present circumstance where information sources have become diverse among the general population, and the widely-used social media bring risks in distributing misinformation and proliferatinganti-vaccination sentiment.41–43 We found that the official channels, including the governments and the health care workers were still trusted by the Chinese general. But unlike the previous online survey which reported that the public primarily used the Internet to obtain COVID-19 vaccine information, our field study further identified differences in information sources between the two age groups.30 Compared with adults aged 18–59 who used diverse sources, the elderly used much fewer types of sources for COVID-19 vaccination information and relied more on traditional media (86.2%) and family, relatives and friends (57.9%). The difference was also found regarding the most trusted sources: a higher proportion of the elderly chose television and/or radio (26.8%), and family, relatives, friends (10.8%). The less access of the elderly to the new media where the information of the disease and vaccine is being updated most frequently may also contribute to their less positive perception for the vaccination.42,43 So, our findings highlight that though current practices have focused on creatively leveraging social media platforms in promoting acceptance, there is a necessity to encourage the authorities, including the government and health workers, to release tailored information via frequently used ways of targeted groups.16,17,41–43 Particularly, for the elderly who have less health literacy and access to new media, the importance of traditional media and neighboring people to provide vaccination recommendations should not be underestimated.41

Since March 2021, China has expanded the mass vaccination program for the general publicin addition to key population groups.58 And the vaccination for the elderly have also been proposed since April.59,60 Though with a slow start, the vaccination campaign in China has made significant progress so far. By September 18, China had administered 2.17 billion doses, making the coverage rate (at least one dose) of 78% among the general population.61 According to available reports in China, the coverage rate has reached 99.4% among people aged 18 and above in Zhejiang province, and 99.23% among people aged 12 and above in Guangdong province.62,63 And out of the 264 million elderly aged 60 and above nationally, over 200 million have got at least one dose of COVID-19 vaccine, making the coverage about 75.7% among the elderly.64 The actual vaccine uptake among the population aged 18–59 are at the same level or higher compared with the vaccine acceptance surveyd in our study, which may due to the effect of comprehensive promotion strategies, including the free-vaccination policy, communication campaigns by agencies like governments and centers for disease control and prevention (CDCs), and promotion of the immunization service capacity.49 The free-vaccination policy has been reported to enhance the vaccination intention by eliminating the economic barrier, and news conferences have been held weekly or sometimes daily to update the latest progress in vaccine development and vaccination, to clarify rumors and questions, and to provide recommendations.11,38,49,58,61,62,64 However, the coverage rate of the elderly is lower than the our surveyed intention rate, which may due to the vaccination for the elderly being started soon and the elderly being with lower recognition on the vaccination importance

This study has several limitations. First, the questionnaire adopted single item to assess each aspect of the vaccination perceptions, which was based the vaccine hesitancy framework proposed by SAGE group.20 But this would reduce the validation of measures since the construct validity could not be assessed.20,31,36 And some self-reported questions of the questionnaire may result in response bias. Second, causal relationships between the influencing factors and willingness to accept the vaccination could not be established because of the cross-sectional design. Third, the willingness rate to accept vaccination of the total sample may be relatively higher due to the larger sample size in Hubei province who experienced a severe pandemic impact. In addition, the participants were recruited using convenience sampling in the communities and villages, hindering the use of weighted estimation methods and the representative of the sample. Future studies and investigations are needed to monitor the public perception, willingness of acceptance, and uptake of COVID‐19 vaccination with the progress of a national vaccination program, and assess the effects of vaccination programs in terms of access, distribution, coverage, and equity.

On December 30, 2020, China approved its first COVID‐19 vaccine, Sinopharm, for public use and has been preparing a mass vaccination program.11 During this period, the field survey identified a high willingness rate of the general population to accept future COVID-19 vaccine in China, with the elderly showing a lower intention than the adults aged 18–59. To reach the herd immunity against COVID-19, our finding highlights the importance of comprehensive strategies in the vaccination campaign, including promoting public vaccination attitude and perception by health communications and education, enhancing vaccination accessibility, affordability and convenience, alleviating concern about vaccine safety. More importantly, the differences found among people of different ages and NCD status on the vaccine acceptance, reasons of vaccine hesitancy, and information sources suggested that tailored promotion strategies should be designed to address specific concerns among different population groups and conducted via their trusted sources.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank investigators from local community health centers or community resident committees for conducting the field survey, and staff members from central or provincial Centers for Disease Prevention and Control for organizing the collaboration, training investigators and conducting the field survey.

Appendix A.

Table A1.

Influence of demographic factors on COVID-19 vaccination intention among the total sample (n = 7259)

| Characteristics | aOR | p-Value | 95%CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.994 | 0.021 | 0.989–0.999 |

| Have NCD (yes vs. no) | 0.979 | 0.790 | 0.836–1.146 |

| Health status | 1.004 | 0.097 | 0.999–1.009 |

| Male (vs. female) | 1.014 | 0.834 | 0.893–1.150 |

| Education (vs. primary school and below) | |||

| Middle or high school | 1.341 | 0.002 | 1.118–1.609 |

| Senior high school | 1.343 | 0.003 | 1.107–1.630 |

| Associate/bachelor and above | 1.319 | 0.013 | 1.060–1.642 |

| Married (vs. single/divorced/widowed) | 1.035 | 0.685 | 0.875–1.225 |

| Employed (vs. unemployed) | 1.363 | <0.001 | 1.183–1.571 |

| Annual household income in 2019 (vs. ≤ CNY 50,000) | |||

| CNY 50,000–100,000 | 0.881 | 0.108 | 0.755–1.028 |

| CNY 100,000–150,000 | 0.973 | 0.797 | 0.789–1.200 |

| ≥CNY 150,000 | 0.691 | 0.001 | 0.550–0.868 |

| Urban (vs. rural) | 1.023 | 0.761 | 0.884–1.184 |

| Province (vs. Jilin) | |||

| Guangdong | 1.543 | <0.001 | 1.240–1.921 |

| Zhejiang | 1.484 | 0.001 | 1.170–1.881 |

| Hubei | 3.934 | <0.001 | 3.173–4.877 |

| Gansu | 1.113 | 0.308 | 0.906–1.367 |

| Chongqing | 3.545 | <0.001 | 2.748–4.574 |

Respondents who had vaccine hesitancy (reported “unsure” or “no” for the vaccination) as reference group.

Table A2.

Associations between COVID-19 vaccination intention and perception among respondents in groups of adult aged 18–59 and the elderly, (%, 95% CI)

| Items | Adults aged 18–59 |

The elderly aged 60 and above |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total sample (n = 3928) |

Willingness to accept COVID-19 vaccination |

Total sample (n = 3331) |

Willingness to accept COVID-19 vaccination |

|||||

| Yes (n = 3329) |

Unsure or no (n = 599) |

p-Valuea | Yes (n = 2634) |

Unsure or no (n = 697) |

p-Valuea | |||

| Complacency measures | ||||||||

| Perceived risk of COVID-19 infection | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||

| High | 30.50 (29.06, 31.94) | 31.90 (30.32, 33.48) | 22.70 (19.35, 26.06) | 23.78 (22.33, 25.22) | 26.88 (25.19, 28.57) | 12.05 (9.63, 14.47) | ||

| Fair or low | 69.50 (68.06, 70.94) | 68.10 (66.52, 69.68) | 77.30 (73.94, 80.65) | 76.22 (74.78, 77.67) | 73.12 (71.43, 74.81) | 87.95 (85.53, 90.37) | ||

| Perceived severity of COVID-19 diseases | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||

| High | 83.50 (82.34, 84.66) | 85.31 (84.11, 86.51) | 73.46 (69.92, 76.99) | 79.74 (78.37, 81.10) | 83.41 (81.99, 84.83) | 65.85 (62.33, 69.37) | ||

| Fair or low | 16.50 (15.34, 17.66) | 14.69 (13.49, 15.89) | 26.54 (23.01, 30.08) | 20.26 (18.90, 21.63) | 16.59 (15.17, 18.01) | 34.15 (30.63, 37.67) | ||

| Importance of COVID-19 vaccination for myself | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||

| Important | 86.05 (84.97, 87.13) | 92.25 (91.34, 93.16) | 51.59 (47.58, 55.59) | 79.41 (78.03, 80.78) | 89.41 (88.23, 90.58) | 41.61 (37.95, 45.27) | ||

| Fair or not important | 13.95 (12.87, 15.03) | 7.75 (6.84, 8.66) | 48.41 (44.41, 52.42) | 20.59 (19.22, 21.97) | 10.59 (9.42, 11.77) | 58.39 (54.73, 62.05) | ||

| Importance of COVID-19 vaccination for others (e.g. family, friends, neighbors, etc.) | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||

| Important | 87.63 (86.60, 88.66) | 93.30 (92.45, 94.15) | 56.09 (52.12, 60.07) | 81.15 (79.82, 82.48) | 90.51 (89.39, 91.63) | 45.77 (42.07, 49.47) | ||

| Fair or not important | 12.37 (11.34, 13.40) | 6.70 (5.85, 7.55) | 43.91 (39.93, 47.88) | 18.85 (17.52, 20.18) | 9.49 (8.37, 10.61) | 54.23 (50.53, 57.93) | ||

| Confidence measures | ||||||||

| Perceived safety of COVID-19 vaccines | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||

| Safe | 65.05 (63.56, 66.54) | 71.76 (70.23, 73.29) | 27.71 (24.13, 31.30) | 63.58 (61.95, 65.22) | 72.63 (70.92, 74.33) | 29.41 (26.03, 32.79) | ||

| Unsure or not safe | 34.95 (33.46, 36.44) | 28.24 (26.71, 29.77) | 72.29 (68.70 75.87) | 36.42 (34.78, 38.05) | 27.37 (25.67, 29.08) | 70.59 (67.21, 73.97) | ||

| Perceived effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||

| Effective | 68.30 (66.84, 69.76) | 75.22 (73.75, 76.68) | 29.88 (26.22, 33.55) | 65.51 (63.89, 67.12) | 74.98 (73.33, 76.64) | 29.7 (26.31, 33.09) | ||

| Unsure or not effective | 31.70 (30.24, 33.16) | 24.78 (23.32, 26.25) | 70.12 (66.45, 73.78) | 34.49 (32.88, 36.11) | 25.02 (23.36, 26.67) | 70.3 (66.91, 73.69) | ||

| Trust in health workers who providing vaccination information and suggestions | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||

| Trust | 90.17 (89.24, 91.10) | 94.23 (93.44, 95.02) | 67.61 (63.87, 71.36) | 84.93 (83.71, 86.14) | 92.37 (91.36, 93.38) | 56.81 (53.14, 60.49) | ||

| Fair or not trust | 9.83 (8.90 10.76) | 5.77 (4.98, 6.56) | 32.39 (28.64, 36.13) | 15.07 (13.86, 16.29) | 7.63 (6.62, 8.64) | 43.19 (39.51, 46.86) | ||

| Trust in governments on providing vaccination information and suggestions | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||

| Trust | 89.59 (88.63, 90.55) | 93.60 (92.77, 94.43) | 67.28 (63.52, 71.04) | 85.05 (83.84, 86.26) | 92.98 (92.00, 93.95) | 55.09 (51.4, 58.79) | ||

| Fair or not trust | 10.41 (9.45, 11.37) | 6.40 (5.57, 7.23) | 32.72 (28.96, 36.48) | 14.95 (13.74, 16.16) | 7.02 (6.05, 8.00) | 44.91 (41.21, 48.60) | ||

aUnivariable associations between COVID-19 vaccination intention and perception measures among respondents in two age groups, respectively, by Chi-square tests.

Funding Statement

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Author's contributions

JW, BY and XL (Xinran Lu) contributed equally to this paper. WY and HF conceived the presented idea. WY, HF, JW, XL (Xiaoxue Liu), LL, SG, HZ, XL (Xiaozhen Lai) developed the design and the questionnaire. WY, XL (Xiaoxue Liu), LL, SG conducted the field survey. HF, JW, XL (Xiaoxue Liu) performed the analysis. JW, XL (Xinran Lu) wrote the first draft. BY, HF, LL, YL, YF, RJ, JG, YH, XL (Xun Liang) commented on the draft and revised the manuscript. All authors discussed the results and contributed to the final manuscript.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed on the publisher’s website at https://doi.org/10.1080/21645515.2021.2009290

References

- 1.Huang C, Wang Y, Xingwang L, Ren L, Zhao J, Hu Y, Zhang L, Fan G, Xu J, Gu X, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.The great lockdown: worst economic downturn since the great depression – IMF Blog. [accessed 2021 May 20]. https://blogs.imf.org/2020/04/14/the-great-lockdown-worst-economic-downturn-since-the-great-depression/.

- 3.WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) dashboard | WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) dashboard with vaccination data. [accessed 2021 March 26]. https://covid19.who.int/.

- 4.Lurie N, Saville M, Hatchett R, Halton J.. Developing Covid-19 vaccines at pandemic speed. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(21):1969–73. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2005630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Draft landscape and tracker of COVID-19 candidate vaccines . [accessed 2021 March 29]. https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/draft-landscape-of-covid-19-candidate-vaccines.

- 6.Wouters OJ, Shadlen KC, Salcher-Konrad M, Pollard AJ, Larson HJ, Teerawattananon Y, Jit M.. Challenges in ensuring global access to COVID-19 vaccines: production, affordability, allocation, and deployment. LANCET. 2021;397(10278):1023–34. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00306-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.COVID-19 vaccines. [accessed 2021 March 27]. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/covid-19-vaccines.

- 8.COVID-19 vaccination first phase priority groups - GOV.UK. [accessed 2021 May 27]. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/covid-19-vaccination-care-home-and-healthcare-settings-posters/covid-19-vaccination-first-phase-priority-groups.

- 9.ACIP COVID-19 Vaccine Recommendations | CDC. [accessed 2021 May 27]. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/hcp/acip-recs/vacc-specific/covid-19.html.

- 10.Rosen B, Waitzberg R, Israeli A. Israel’s rapid rollout of vaccinations for COVID-19. ISR J HEALTH POLICY. 2021;10(1). doi: 10.1186/s13584-021-00440-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Press Conference of the Joint Prevention and Control Mechanism of the State Council on December . 2020. 31 [accessed 2021 March 20]. http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/gwylflkjz143/index.htm.

- 12.Lazarus JV, Ratzan SC, Palayew A, Gostin LO, Larson HJ, Rabin K, Kimball S, El-Mohandes A. A global survey of potential acceptance of a COVID-19 vaccine. NAT MED. 2021;27(2):225–28. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-1124-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Neumann-Böhme S, Varghese NE, Sabat I, Barros PP, Brouwer W, van Exel J, Schreyögg J, Stargardt T. Once we have it, will we use it? A European survey on willingness to be vaccinated against COVID-19. Eur J Health Econ. 2020;21(7):977–82. doi: 10.1007/s10198-020-01208-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dror AA, Eisenbach N, Taiber S, Morozov NG, Mizrachi M, Zigron A, Srouji S, Sela E. Vaccine hesitancy: the next challenge in the fight against COVID-19. EUR J EPIDEMIOL. 2020;35(8):775–79. doi: 10.1007/s10654-020-00671-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Engineering And Medicine National Academies Of Sciences . Vaccine access and hesitancy: part one of a workshop series: proceedings of a workshop—in brief. Washington (DC): The National Academies Press; 2020. p. 5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Buttenheim AM. SARS-CoV-2 vaccine acceptance: we may need to choose our battles. ANN INTERN MED. 2020;173:1018–19. doi: 10.7326/M20-6206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chevallier C, Hacquin AS, Mercier H. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy: shortening the last mile. TRENDS COGN SCI. 2021;25(5):331–33. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2021.02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Laine C, Cotton D, Moyer DV. COVID-19 vaccine: promoting vaccine acceptance. ANN INTERN MED. 2021;174(2):252–53. doi: 10.7326/M20-8008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dubé E, and MacDonald NE. Chapter 26 - vaccine acceptance: barriers, perceived risks, benefits, and irrational beliefs. In: Bloom BR, and Lambert P-H, editors. The vaccine book. 2nd ed. Cambridge, MA, USA: Academic Press;2016. p.507–528. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Report of the Sage Working Group on Vaccine Hesitancy. [accessed 2021 March 2]. https://www.who.int/immunization/sage/meetings/2014/october/1_Report_WORKING_GROUP_vaccine_hesitancy_final.pdf.

- 21.Larson HJ, Jarrett C, Eckersberger E, Smith DMD, Paterson P. Understanding vaccine hesitancy around vaccines and vaccination from a global perspective: a systematic review of published literature, 2007–2012. Vaccine. 2014;32(19):2150–59. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.01.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Larson HJ, Cooper LZ, Eskola J, Katz SL, Ratzan S. Addressing the vaccine confidence gap. LANCET. 2011;378(9790):526–35. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60678-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kelly BJ, Southwell BG, McCormack LA, Bann CM, MacDonald PDM, Frasier AM, Bevc CA, Brewer NT, Squiers LB. Predictors of willingness to get a COVID-19 vaccine in the U.S. BMC Infect Dis. 2021;21(1). doi: 10.1186/s12879-021-06023-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kreps S, Prasad S, Brownstein JS, Hswen Y, Garibaldi BT, Zhang B, Kriner DL. Factors associated with US adults’ likelihood of accepting COVID-19 vaccination. JAMA Network Open. 2020;3(10):e2025594. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.255942020-10-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nguyen KH, Srivastav A, Razzaghi H, Williams W, Lindley MC, Jorgensen C, Abad N, Singleton JA. COVID-19 vaccination intent, perceptions, and reasons for not vaccinating among groups prioritized for early vaccination - United States, September and December 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70(6):217–22. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7006e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schwarzinger M, Watson V, Arwidson P, Alla F, Luchini S. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in a representative working-age population in France: a survey experiment based on vaccine characteristics. Lancet Public Health. 2021;6(4):e210–21. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(21)00012-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lin C, Pikuei T, Beitsch LM. Confidence and receptivity for COVID-19 vaccines: a rapid systematic review. Vaccines. 2021;9(1):16. doi: 10.3390/vaccines90100162020-12-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Robinson E, Jones A, Lesser I, Michael D. International estimates of intended uptake and refusal of COVID-19 vaccines: a rapid systematic review and meta-analysis of large nationally representative samples. VACCINE. 2021;39(15):2024–34. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Graffigna G, Palamenghi L, Boccia S, Barello S. Relationship between citizens’ health engagement and intention to take the COVID-19 vaccine in Italy: a mediation analysis. Vaccines. 2020;8(4):576. doi: 10.3390/vaccines80405762020-10-01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang Y, Luo X, Ma ZF. Willingness of the general population to accept and pay for COVID-19 vaccination during the early stages of COVID-19 pandemic: a nationally representative survey in mainland China. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2021;17(6):1622–27. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2020.1847585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang J, Jing R, Lai X, Zhang H, Lyu Y, Knoll MD, Fang H. Acceptance of COVID-19 Vaccination during the COVID-19 Pandemic in China. Vaccines. 2020;8(3):482. doi: 10.3390/vaccines80304822020-08-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Harapan H, Wagner AL, Yufika A, Winardi W, Anwar S, Gan AK, Setiawan AM, Rajamoorthy Y, Sofyan H, Mudatsir M. Acceptance of a COVID-19 vaccine in southeast asia: a cross-sectional study in Indonesia. Front Public Health. 2020:8. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.003812020-07-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yoda T, Katsuyama H. Willingness to Receive COVID-19 Vaccination in Japan. Vaccines. 2021;9(1):48. doi: 10.3390/vaccines90100482021-01-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen S, Yang J, Yang W, Wang C, Barnighausen T. COVID-19 control in China during mass population movements at New Year. Lancet. 2020;395(10226):764–66. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30421-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Burki T. China’s successful control of COVID-19. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20(11):1240–41. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30800-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang J, Xinran L, Lai X, Lyu Y, Zhang H, Fenghuang Y, Jing R, Li L, Yu W, Fang H, et al. The changing acceptance of COVID-19 vaccination in different epidemic phases in China: Longitudinal study A. Vaccines. 2021;9(3):191. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9030191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lin Y, Zhijian H, Zhao Q, Alias H, Danaee M, Wong LP. Understanding COVID-19 vaccine demand and hesitancy: a nationwide online survey in China. PLOS NEGLECT TROP D. 2020;14(12):e8961. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.00089612020-12-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Press Conference of the Joint Prevention and Control Mechanism of the State Council on January. 2021. 13 [accessed 2021 March 20]. http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/gwylflkjz145/index.htm.

- 39.Baumgaertner B, Ridenhour BJ, Justwan F, Carlisle JE, Miller CR. Risk of disease and willingness to vaccinate in the United States: a population-based survey. PLoS Med. 2020;17(10):e1003354. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lazarus JV, Wyka K, Rauh L, Rabin K, Ratzan S, Gostin LO, Larson HJ, El-Mohandes A. Hesitant or not? The association of age, gender, and education with potential acceptance of a COVID-19 vaccine: a country-level analysis. J Health Commun. 2020;25(10):799–807. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2020.1868630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Verger P, Eve D. Restoring confidence in vaccines in the COVID-19 era. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2020;19(11):991–93. doi: 10.1080/14760584.2020.1825945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Puri N, Coomes EA, Haghbayan H, Gunaratne K. Social media and vaccine hesitancy: new updates for the era of COVID-19 and globalized infectious diseases. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2020;16(11):2586–93. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2020.1780846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schiavo R. Vaccine communication in the age of COVID-19: getting ready for an information war. J Commun Healthc. 2020;13(2):73–75. doi: 10.1080/17538068.2020.1778959. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Coronavirus (COVID-19) vaccinations - statistics and research - our world in data. [accessed 2021 March 27]. https://ourworldindata.org/covid-vaccinations?country=OWID_WRL.

- 45.Wu S, Yang P, Li H, Ma C, Zhang Y, Wang Q. Influenza vaccination coverage rates among adults before and after the 2009 influenza pandemic and the reasons for non-vaccination in Beijing, China: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:636. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Brien S, Kwong JC, Buckeridge DL. The determinants of 2009 pandemic A/H1N1 influenza vaccination: a systematic review. Vaccine. 2012;30(7):1255–64. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.12.089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chen M, Li Y, Chen J, Wen Z, Feng F, Zou H, Fu C, Chen L, Shu Y, Sun, C. An online survey of the attitude and willingness of Chinese adults to receive COVID-19 vaccination. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2021;1–10. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2020.1853449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wong LP, Alias H, Wong PF, Lee HY, AbuBakar S. The use of the health belief model to assess predictors of intent to receive the COVID-19 vaccine and willingness to pay. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2020;16(9):2204–14. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2020.1790279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Liu R, Zhang Y, Nicholas S, Leng A, Maitland E, Wang J. COVID-19 vaccination willingness among Chinese adults under the free vaccination policy. Vaccines. 2021;9(3):292. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9030292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tsai F, Yang H, Lin C, Liu JZ. Acceptability of COVID-19 vaccines and protective behavior among adults in Taiwan: associations between risk perception and willingness to vaccinate against COVID-19. INT J ENV RES PUB HE. 2021;18(11):5579. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18115579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Murphy J, Vallieres F, Bentall RP, Shevlin M, McBride O, Hartman TK, McKay R, Bennett K, Mason L, Gibson-Miller J. Psychological characteristics associated with COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and resistance in Ireland and the United Kingdom. NAT COMMUN. 2021;12(1):29. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-20226-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sethi S, Kumar A, Mandal A, Shaikh M, Hall CA, Kirk JMW, Moss P, Brookes MJ, Basu S. The UPTAKE study: a cross-sectional survey examining the insights and beliefs of the UK population on COVID-19 vaccine uptake and hesitancy. BMJ OPEN. 2021;11(6):e48856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wong MCS, Wong ELY, Huang J, Cheung AWL, Law K, Chong MKC, Ng RWY, Lai CKC, Boon SS, Lau JTF, et al. Acceptance of the COVID-19 vaccine based on the health belief model: a population-based survey in Hong Kong. VACCINE. 2021;39(7):1148–56. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.12.083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Alabdulla M, Reagu SM, Al Khal A, Elzain M, Jones RM. COVID‐19 vaccine hesitancy and attitudes in Qatar: a national cross‐sectional survey of a migrant‐majority population. Influenza Other Resp. 2021;15(3):361–70. doi: 10.1111/irv.12847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gan L, Chen Y, Hu P, Wu D, Zhu Y, Tan J, Li Y, Zhang D. Willingness to receive SARS-CoV-2 vaccination and associated factors among Chinese adults: a cross sectional survey. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(4). doi: 10.3390/ijerph18041993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rui M, Suo L, Lu L, Pang X. Willingness of the general public to receive the COVID-19 vaccine during a second-level alert — Beijing municipality, China, May 2020. China CDC Weekly. 2021;3(25):531–37. doi: 10.46234/ccdcw2021.118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.These Countries Did Well With Covid . So Why Are They Slow on Vaccines? The New York Times. [accessed 2021 May 27]. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/04/17/world/asia/Japan-south-Korea-Australia-vaccines.html.

- 58.Press Conference of the Joint Prevention and Control Mechanism of the State Council on March . 2020. 28 [accessed 2021 Sept 21]. http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/gwylflkjz153/index.htm.

- 59.Question and Answer for COVID-19 Vaccination. [accessed 2021 Spet 21]. http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2021-04/01/content_5597357.htm.

- 60.Mohamadi M, Lin Y, Vulliet MVS, Flahault A, Rozanova L, Fabre G. COVID-19 vaccination strategy in China: a case study. Epidemiologia. 2021;2(3):402–25. doi: 10.3390/epidemiologia2030030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Press Conference of the Joint Prevention and Control Mechanism of the State Council on September. 2020. 18 [accessed 2021 Spet 21]. http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/gwylflkjz153/index.htm.

- 62.The 76th Press Conference on COVID-19 Prevention and Control in Zhejiang Province. [accessed 2021 Spet 21]. https://baijiahao.baidu.com/s?id=1708413801540021226&wfr=spider&for=pc.

- 63.In Guangdong, 90% of people aged 12 and above were vaccinated against COVID-19. [accessed 2021 Spet 21]. https://m.gmw.cn/baijia/2021-09/08/1302561119.html.

- 64.Press Conference of the Joint Prevention and Control Mechanism of the State Council on September . 2020. 6 [accessed 2021 Spet 21]. http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/gwylflkjz153/index.htm.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.