Abstract

Objective:

Research suggests that impulsivity is a risk factor for problem drinking, but prior studies have yet to examine typical drinking context as a potential moderator of relations between impulsivity and drinking outcomes. Guided by Person-Environment Transactions Theory, the current study tested whether five facets of impulsivity (negative urgency, positive urgency, lack of premeditation, lack of perseverance, and sensation seeking) interacted with typical drinking context to prospectively predict drinking quantity.

Method:

Young adult participants (N = 448; mean age = 22.27) were recruited from a southwestern university and the surrounding community. Data from a baseline survey (Time [T] 1) and a 1-year follow-up (T2) were used for the current analyses. Impulsivity (UPPS-P Impulsive Behavior Scale), typical drinking context, and typical drinking quantity were assessed at T1, and typical drinking quantity at T2.

Results:

Context items were loaded onto latent factors comprising high-arousal (e.g., at a tailgate, large house party) and low-arousal (e.g., at a restaurant, on a date) drinking contexts. In univariate (separated by UPPS-P facet) and multivariate (UPPS-P facets together) models, lack of premeditation and positive urgency interacted with high-arousal drinking contexts to predict T2 drinking, such that individuals at high/mean levels of impulsivity drank more heavily the more frequently they drank in high-arousal contexts. Only interactions in univariate models remained significant after a false discovery correction, although effect sizes were very similar across univariate and multivariate models.

Conclusions:

Individuals high in positive urgency and lack of premeditation may be particularly vulnerable to riskier drinking behavior in high-arousal environments. Findings advance the literature on context-specific cues that may be important intervention targets, particularly for individuals high in positive urgency and lack of premeditation.

Heavier drinking patterns in young adulthood represent a significant public health concern. Rates of young adult drinking and alcohol use disorder (AUD) have been rising since the early 2000s, and several alcohol-related problems—including hangovers, risky sexual behavior, and alcohol-induced blackouts—are common in young adulthood (Barnett et al., 2014; Rohsenow et al., 2007; Waddell et al., 2021a; Wetherill & Fromme, 2016) Considering the societal impact of heavier drinking patterns, it is crucial to understand prospective risk factors to target via prevention efforts.

One consistent risk factor for heavier drinking is impulsivity (Dick et al., 2010; Henges & Marczinski, 2012; Magid et al., 2007; Stacy et al., 1993), broadly defined as the proclivity to engage in rash, unplanned action with little regard for consequences (Moeller et al., 2001). Modern theories of impulsivity suggest that facets of impulsivity may provide more precise prediction of heavier drinking and alcohol-related consequences (Lynam et al., 2007; Whiteside & Lynam, 2001). Meta-analytic findings suggest that a lack of premeditation (i.e., lacking planning/forethought) and lack of perseverance (i.e., task switching) are the strongest predictors of heavier drinking quantity, sensation seeking (i.e., thrill, novelty seeking) is the strongest predictor of binge drinking frequency, and both positive and negative urgency (i.e., rash action in the presence of positive or negative mood, respectively) are the strongest predictors of alcohol-related problems (Coskunpinar et al., 2013; Cyders & Smith, 2008; Smith & Cyders, 2016). However, studies testing the additive/unique effects of each facet above and beyond other impulsivity facets are less common, despite evidence that some facets of impulsivity uniquely predict drinking outcomes when other facets are accounted for (McCarty et al., 2017; Waddell et al., 2021b; Waddell et al., 2022).

In addition to examining facets of impulsivity, it may be important to examine the extent to which impulsivity differentially affects drinking outcomes based on an individual's typical drinking context. Reactive-person transactions, an aspect of Person-Environment Transactions Theory (Caspi & Roberts, 2001), suggest that individuals perceive and attend to different aspects of an environment (reactive transactions) based on their personality characteristics. Consistent with this model, studies show that individuals high in impulsivity react and attend to appetitive drinking outcomes/cues (Anderson et al., 2003; McCarthy et al., 2001; Settles et al., 2010; Smith & Anderson, 2001) while discounting negative, aversive ones.

Thus, impulsive individuals may gain the most reward from high-arousal drinking contexts. In support of this possibility, impulsivity is associated with feeling more stimulant alcohol effects (e.g., elated, excited; Berey et al., 2019; Leeman et al., 2014; Waddell et al., 2021c, and stimulant alcohol effects are associated with drinking in physically stimulating and social contexts (Corbin et al., 2015; Fairbairn & Sayette, 2013; Kirkpatrick & De Wit, 2013; Sayette et al., 2012). In addition, contexts that are inherently high arousal/exciting, such as those that include drinking games and pregaming, are related to heavier drinking (Cox et al., 2019; Moser et al., 2014), and meta-analytic findings suggest that heavier drinking is more likely in large group contexts (Stanesby et al., 2019). Taken together, these studies suggest that impulsive individuals may be particularly vulnerable to the reward/excitability associated with highly arousing drinking contexts, which may then predict heavier drinking.

Although highly arousing drinking contexts may confer greater risk across impulsivity facets, it is also possible that increased risk in high-arousal drinking contexts is limited to particular aspects of impulsivity. For example, individuals high in positive urgency and sensation seeking may be most vulnerable to the positive-affective cues associated with highly arousing drinking environments. In support of this possibility, Wardell et al. (2012) found that the behavioral activation system, most closely aligned with positive urgency and sensation seeking, was related to positively reinforcing alcohol expectancies (i.e., activity and performance enhancement). In addition, Scott and Corbin (2014) found that sensation seeking was related to stronger stimulant subjective effects, regardless of whether an individual received alcohol or placebo. Thus, individuals high in both traits may drink more heavily in highly arousing contexts. In contrast, individuals high in negative urgency, who commonly endorse coping motives (Settles et al., 2010) and have more internalizing symptoms (Smith et al., 2013), may be more attentive to the relaxing/tension-reducing effects of drinking in lower arousal drinking contexts.

To address these possibilities, the current study tested whether unique aspects of drinking context moderate effects of UPPS-P Impulsive Behavior Scale impulsivity facets on future drinking behavior. To our knowledge, no studies have looked at context by UPPS-P impulsivity interactions, which are theoretically appealing within the context of Person-Environment Transactions Theory (Caspi & Roberts, 2001).

The current study also tested the factor structure of typical drinking contexts. Only one study to our knowledge has conducted factor analytic work on typical drinking contexts (O'Hare, 1997), and the items in that study largely measured drinking motivation (i.e., negative affect coping drinking contexts).

Based on prior research, we hypothesized that two latent factors would emerge from 12 drinking context items (i.e., high- vs. low-arousal drinking contexts). With respect to the primary aim of the study, we hypothesized that both positive urgency and sensation seeking would interact with more frequent drinking in high-arousal drinking contexts to prospectively predict heavier drinking.

Finally, we hypothesized that negative urgency would interact with more frequent drinking in low-arousal drinking contexts to prospectively predict heavier drinking. Examination of potential interactions between drinking contexts and both the lack of premeditation and the lack of perseverance were considered exploratory.

Method

Participants

Participants (N = 448) were recruited from a southwestern university and the surrounding community to participate in a laboratory-based study of subjective alcohol response. Eligible participants were ages 21–25 and endorsed at least one past-month heavy drinking episode. Participants were excluded if they reported serious mental illness or other medical conditions, use of psychotropic medication/pain medication, negative physical reactions to alcohol, use of illicit drugs, daily marijuana use, past treatment or currently seeking treatment for alcohol-related problems, current pregnancy or nursing, alcohol dependence, or a past-month mood or anxiety disorder. The final sample included similar numbers of men and women (n = 253; 56.5% male), had a mean age of 22.27 years (SD = 1.25), and was 66.1% White and 71.7% non-Hispanic/Latinx (see Table 1 for descriptive statistics). Seventy-nine percent of the sample were undergraduate or graduate students.

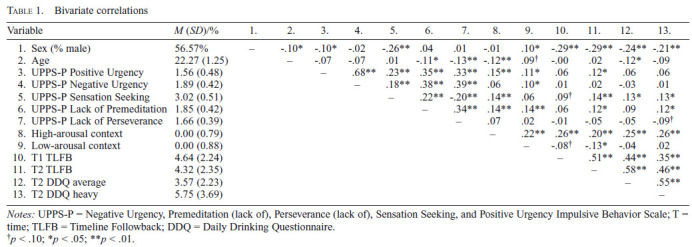

Table 1.

Bivariate correlations

| Variable | M (SD)/% | 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | 9. | 10. | 11. | 12. | 13. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Sex (% male) | 56.57% | - | −.10* | −.10* | −.02 | −.26** | .04 | .01 | −.01 | .10* | −.29** | −.29** | −.24** | −.21** |

| 2. Age | 22.27 (1.25) | - | −.07 | −.07 .01 | −.11* | −.13** | −.12** | .09† | −.00 | .02 | −.12* | −.09 | ||

| 3. UPPS-P Positive Urgency | 1.56 (0.48) | - | − .68** | .23** | .35** | .33** | .15** | .11* | .06 | .12* | .06 | .06 | ||

| 4. UPPS-P Negative Urgency | 1.89 (0.42) | - | − .18** | .38** | .39** | .06 | .10* | .01 | .02 | −.03 | .01 | |||

| 5. UPPS-P Sensation Seeking | 3.02 (0.51) | - | .22** | −.20** | .14** | .06 | .09† | .14** | .13* | .13* | ||||

| 6. UPPS-P Lack of Premeditation | 1.85 (0.42) | - | .34** | .14** | .14** | .06 | .12* | .09 | .12* | |||||

| 7. UPPS-P Lack of Perseverance | 1.66 (0.39) | - | .07 | .02 | −.01 | −.05 | −.05 | −.09† | ||||||

| 8. High-arousal context | 0.00 (0.79) | - | .22** | .26** | .20** | .25** | .26** | |||||||

| 9. Low-arousal context | 0.00 (0.88) | - | −.08t | −.13* | −.04 | .02 | ||||||||

| 10. T1 TLFB | 4.64 (2.24) | - | .51** | .44** | .35** | |||||||||

| 11. T2TLFB | 4.32 (2.35) | - | .58** | .46** | ||||||||||

| 12. T2 DDQ average | 3.57 (2.23) | - | .55** | |||||||||||

| 13. T2 DDQ heavy | 5.75 (3.69) | - |

Notes: UPPS-P = Negative Urgency, Premeditation (lack of), Perseverance (lack of), Sensation Seeking, and Positive Urgency Impulsive Behavior Scale; T = time; TLFB = Timeline Followback; DDQ = Daily Drinking Questionnaire.

p < .10;

p < .05;

p < .01.

Procedure

All study procedures were approved by the Arizona State University Institutional Review Board. Participants were first screened via phone and, if eligible, came into the lab for a baseline assessment. Participants were administered a structured clinical interview and a battery of questionnaires. Eligible participants returned for a placebo-controlled alcohol challenge and were re-contacted for follow-ups. The current study used data from the baseline assessment (T1) and a 12-month follow-up (T2). Although assessments occurred every 6 months, we used 12-month follow-up data because this assessment included a detailed drinking interview for the past 30 days and a measure that captured drinking over the full 12-month period (Daily Drinking Questionnaire [DDQ]), which allowed us to create a composite measure of drinking behavior over the past year.

Measures

Demographics. Age and sex were assessed at T1.

Alcohol use. Alcohol use was assessed at T1 and T2 via the Timeline Followback (TLFB; Sobell & Sobell, 1992). Participants were given standard drink charts and were encouraged to reference memory aids for accurate reporting. Past-30-day typical drinking quantity was computed as the number of total drinks divided by the number of drinking days. The TLFB has evidenced strong validity and reliability (Carey et al., 2004; Sobell & Sobell, 1992).

At the 12-month follow-up (T2), the DDQ (Collins et al., 1985) was administered to assess average daily drinking quantity (Monday–Sunday) in a typical week and during the heaviest drinking week over the past year. Drinking quantity variables were computed as the total number of drinks divided by the number of drinking days. To create a comprehensive index of drinking quantity, we created a latent variable of TLFB drinking quantity, DDQ average drinking quantity, and DDQ heaviest drinking quantity measured at T2. The current study focused on typical drinking quantity rather than binge drinking frequency, considering modest empirical evidence for the 5+/4+ (for men/women) drink threshold (Jackson, 2008).

Impulsivity. Impulsive personality traits were assessed using the UPPS-P Impulsivity Scale (Lynam et al., 2007). The UPPS-P is a 59-item scale assessing positive urgency (e.g., “When I am really ecstatic, I tend to get out of control”), negative urgency (e.g., “When I am upset, I often act without thinking”), sensation seeking (e.g., “I quite enjoy taking risks”), lack of premeditation (e.g., “I usually think carefully before doing anything” [reverse scored]), and lack of perseverance (e.g., “I almost always finish projects that I start” [reverse scored]) on a scale of 1 (agree strongly) to 4 (disagree strongly). All items were recoded such that higher scores indicated more impulsivity, and all subscales had adequate internal consistency (McDonald's ω = .79–.92).

Typical drinking context. Typical drinking contexts were assessed by asking how often participants drank alcohol in 12 different contexts on a scale of 1 (never) to 7 (always). The 12 contexts included “at a bar,” “at a small house party,” “at a large house party,” “in a car,” “while pre-drinking/pre-gaming,” “while playing a drinking game,” “at a tailgate,” “at a concert,” “at home,” “in a restaurant,” “during a meal,” and “on a date.” Some items have been used in past studies to index social drinking (Waddell et al., 2021d) but have not undergone psychometric evaluation.

Data analytic plan

We used structural equation modeling to determine (a) the factor structure of typical drinking contexts and (b) whether impulsive personality traits moderated the effects of typical drinking context on future drinking behavior. To determine the factor structure of drinking contexts, participants were split into two random samples (each n = 224) for exploratory factor analysis (EFA) in sample 1 and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) in sample 2. For the EFA, a combination of parallel analysis, the scree plot, interpretability of factors, and items per factor were used to determine the optimal factor structure (Jöreskog & Sörbom, 1989; Tabachnick & Fidell, 2001). Direct oblimin rotation allowed for correlated factors. After determining the optimal number of factors, items with low factor loadings (less than .32) and/or high cross-loadings (i.e., greater than .32) were removed (Comrey & Lee, 1992; Tabachnick & Fidell, 2001). The second sample (n = 224) was used to confirm the factor structure using CFA. Finally, using the full data set (N = 448), we estimated a measurement model with typical drinking context latent variables, and resulting factor scores were extracted and used as manifest variables in structural models.

Univariate structural models were estimated to test whether UPPS-P facets (separate models) moderated the effect of typical drinking contexts on the T2 latent drinking quantity variable. Main effects of the UPPS-P facets and drinking context were entered first followed by interaction terms between impulsivity and drinking contexts. To ensure that linear interactions were not obscured by quadratic effects (Belzak & Bauer, 2019), quadratic main effects and quadratic interactions were included; quadratic interactions and main effects were retained only if a significant interaction involving a quadratic term was found. Sex, age, and baseline drinking were covaried in all models and allowed to freely covary.

Next, multivariate models were estimated with all main effects and interactions to test whether UPPS-P and context main effects and their interactions prospectively predicted drinking quantity above and beyond other UPPS-P impulsivity facets and their interactions with context. Because positive and negative urgency were highly correlated (r = .69, p < .001), two models were estimated for each drinking context, one with positive urgency, lack of premeditation, lack of perseverance, and sensation seeking, and the other with negative urgency instead of positive urgency. Main effects were entered first, followed by interaction terms between each UPPS-P facet and the drinking context variable of interest; if quadratic interactions were found in univariate models, their interactions (and lower order main effects) were included in multivariate models. Interactions for each facet tested whether the unique variance in each UPPS-P facet interacted with context to predict T2 drinking quantity above and beyond baseline drinking quantity, the effects of the other UPPS-P facets, and their interactions with drinking context. Covariate effects from univariate models were retained and allowed to freely covary.

All models used maximum likelihood estimation with robust standard errors and full information maximum likelihood to estimate missing data. Adequate model fit was defined as comparative fit index (CFI) and Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI) values near .95, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) values near .06, and standardized root mean squared residual (SRMR) values near .08 (Hu & Bentler, 1999). Significant interactions were probed by estimating simple regression equations and estimating marginal means at 1 SD above the mean, the mean, and 1 SD below the mean of impulsivity (Aiken et al., 1991). Standardized model parameters are shown in the tables.

Because univariate models tested 10 linear interactions and multivariate models tested 16 linear interactions, the Benjamini & Hochberg (1995) procedure was used to adjust the false discovery rate.

Results

Factor analysis of typical drinking context

The item “in a car” was removed before the EFA because of low endorsement (80% indicated no drinking in this context). After removing this item, parallel analysis indicated that a five-factor structure was optimal, and a scree plot identified four factors with eigenvalues above 1. However, the five-factor structure was not viable, as two factors had fewer than three items load onto it; thus, the four- and three-factor models were examined next. In the EFA, the three-and four-factor solutions did not converge because of a large residual correlation between “at a large house party” and “at a small house party.” Consideration of residual correlations is not allowed in EFA, so an Exploratory Structural Equation Model (ESEM; Asparouhov & Muthén, 2009; Marsh et al., 2020) was estimated to allow the residual variances of “at a large house party” and “at a small house party” to freely covary. When allowing the two to freely covary, both the four- and three-factor models converged.

In the four-factor solution, only one item loaded significantly onto the fourth factor. In the three-factor solution, three items loaded significantly onto the third factor, but the item “while pre-drinking/pre-gaming” loaded significantly and highly onto two factors (β1 = .41, β2 = .46), leaving only two viable indicators for factor 3, which had no clear theme. Therefore, four- and three-factor solutions were not considered further. In the two-factor solution, seven items loaded significantly onto the first factor and five loaded onto the second, which largely represented high-arousal and low-arousal drinking contexts. The two-factor solution showed significantly better statistical, Δχ2(10) = 174.93, p < .001, and theoretical fit than the one-factor solution and was therefore retained.

Within the two-factor solution, item narrowing began by removing one item with a loading below .32 (i.e., “at a small house party”; β = .28). Next, we removed one item, “at a concert,” because of a significant cross-loading (β = .37) with low-arousal drinking contexts. After removal of these items, all items in the ESEM loaded onto their respective factors at .35 or above and had no cross-loadings above threshold. Next, a CFA was estimated in random sample 2, which evidenced mediocre model fit, χ2(26) = 64.10, p < .001, RMSEA = .081, CFI = .925, TLI = .896, SRMR = .075. The item “while at home” loaded poorly onto the low-arousal drinking context factor (β = .37), and removal of this item led to adequate model fit, χ2(19) = 31.06, p = .04, RMSEA = .053, CFI = .974, TLI = .962, SRMR = .05; Δχ2(7) = 30.85, p < .001. With all items loaded onto their respective factor, no item loadings were below .45, and internal consistency was good (ω = .78–.82; Table 2). The final CFA was estimated in the full sample (N = 448), and model fit was good, χ2(49) = 48.03, p < .001, RMSEA = .058, CFI = .964, TLI = .947, SRMR = .052.

Table 2.

Confirmatory factor structure

| Variable | b | SE | β |

|---|---|---|---|

| High-arousal context (ω = .78) | |||

| While pre-drinking/pre-gaming | 1.00 | 0.03 | .82 |

| At a large house party | 0.62 | 0.05 | .51 |

| At a bar | 0.43 | 0.05 | .43 |

| While playing a drinking game | 0.82 | 0.04 | .74 |

| At a tailgate or sporting event | 0.90 | 0.04 | .67 |

| Low-arousal context (ω = .82) | |||

| On a date | 1.00 | 0.04 | .81 |

| During a meal | 0.96 | 0.03 | .73 |

| In a restaurant | 0.91 | 0.04 | .80 |

Notes: b = unstandardized beta; β = standardized beta; ω = McDonald's omega.

Although the CFA suggested removing “while at home” from analyses, low-arousal drinking context models were re-run with the inclusion of this item. No additional main effects or interactions emerged, and significant effects from the primary model remained significant.

Structural equation models

First, a measurement model was estimated using scores from the T2 30-day TLFB (β = .67, p < .001), the DDQ-average (β = .83, p < .001), and the DDQ-heavy (β = .72, p < .001). All items loaded significantly onto the T2 drinking factor. Next, a series of interactions were tested between UPPS-P facets and both high-arousal and low-arousal drinking contexts as predictors of T2 drinking quantity.

All structural models fit the data well (Supplemental Table 1). (Supplemental material appears as an online-only addendum to this article on the journal's website.) Although theory guided our use of a reflexive latent variable, models were also re-run with formative variables (i.e., sum scores); however, no nonsignificant effects emerged as significant, and no significant effects became nonsignificant.

Univariate models

Covariate effects were consistent across univariate models (Table 3), such that older age and female sex were associated with less drinking, and heavier T1 drinking was associated with heavier T2 drinking. Across models, more frequent drinking in high-arousal contexts prospectively predicted heavier T2 drinking, whereas drinking in low-arousal contexts was unrelated to T2 drinking. Lack of premeditation prospectively predicted heavier T2 drinking, whereas lack of perseverance prospectively predicted less T2 drinking; however, the premeditation finding was significant only in the low-arousal context model, and the perseverance main effect in the high-arousal context model.

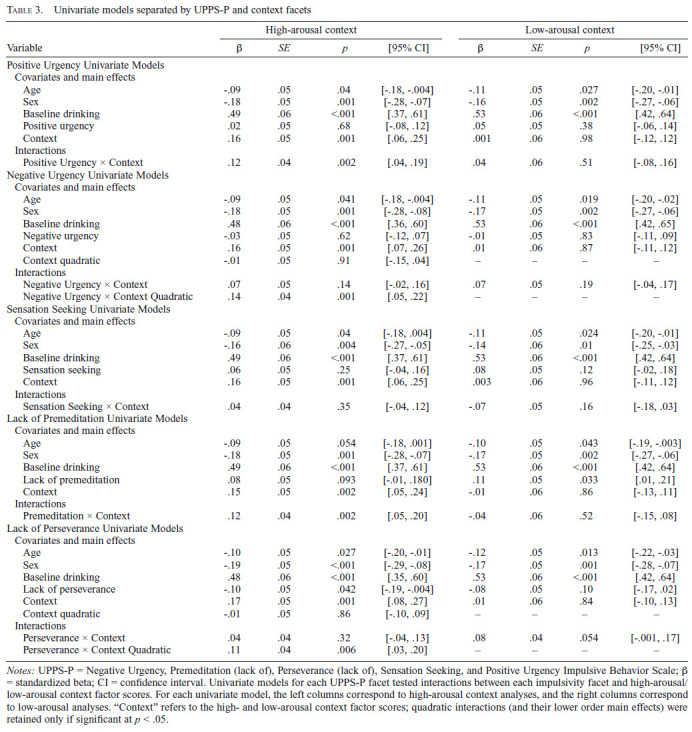

Table 3.

Univariate models separated by UPPS-P and context facets

| Variable | High-arousal context | Low-arousal context | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | SE | p | [95% CI] | β | SE | p | [95% CI] | |

| Positive Urgency Univariate Models | ||||||||

| Covariates and main effects | ||||||||

| Age | −.09 | .05 | .04 | [−.18, −.004] | −.11 | .05 | .027 | [−.20, −.01] |

| Sex | −.18 | .05 | .001 | [−.28, −.07] | −.16 | .05 | .002 | [−.27, −.06] |

| Baseline drinking | .49 | .06 | <.001 | [.37, .61] | .53 | .06 | <.001 | [.42, .64] |

| Positive urgency | .02 | .05 | .68 | [−.08, .12] | .05 | .05 | .38 | [−.06, .14] |

| Context | .16 | .05 | .001 | [.06, .25] | .001 | .06 | .98 | [−.12, .12] |

| Interactions | ||||||||

| Positive Urgency × Context | .12 | .04 | .002 | [.04, .19] | .04 | .06 | .51 | [−.08, .16] |

| Negative Urgency Univariate Models | ||||||||

| Covariates and main effects | ||||||||

| Age | −.09 | .05 | .041 | [−.18, −.004] | −.11 | .05 | .019 | [−.20, −.02] |

| Sex | −.18 | .05 | .001 | [−.28, −.08] | −.17 | .05 | .002 | [−.27, −.06] |

| Baseline drinking | .48 | .06 | <.001 | [.36, .60] | .53 | .06 | <.001 | [.42, .65] |

| Negative urgency | −.03 | .05 | .62 | [−.12, .07] | −.01 | .05 | .83 | [−.11, .09] |

| Context | .16 | .05 | .001 | [.07, .26] | .01 | .06 | .87 | [−.11, .12] |

| Context quadratic | −.01 | .05 | .91 | [−.15, .04] | - | - | - | - |

| Interactions | ||||||||

| Negative Urgency × Context | .07 | .05 | .14 | [−.02, .16] | .07 | .05 | .19 | [−.04, .17] |

| Negative Urgency × Context Quadratic | .14 | .04 | .001 | [.05, .22] | - | - | - | - |

| Sensation Seeking Univariate Models | ||||||||

| Covariates and main effects | ||||||||

| Age | −.09 | .05 | .04 | [−.18, .004] | −.11 | .05 | .024 | [−.20, −.01] |

| Sex | −.16 | .06 | .004 | [−.27, −.05] | −.14 | .06 | .01 | [−.25, −.03] |

| Baseline drinking | .49 | .06 | <.001 | [.37, .61] | .53 | .06 | <.001 | [.42, .64] |

| Sensation seeking | .06 | .05 | .25 | [−.04, .16] | .08 | .05 | .12 | [−.02, .18] |

| Context | .16 | .05 | .001 | [.06, .25] | .003 | .06 | .96 | [−.11, .12] |

| Interactions | ||||||||

| Sensation Seeking × Context | .04 | .04 | .35 | [−.04, .12] | −.07 | .05 | .16 | [−.18, .03] |

| Lack of Premeditation Univariate Models | ||||||||

| Covariates and main effects | ||||||||

| Age | −.09 | .05 | .054 | [−.18, .001] | −.10 | .05 | .043 | [−.19, −.003] |

| Sex | −.18 | .05 | .001 | [−.28, −.07] | −.17 | .05 | .002 | [−.27, −.06] |

| Baseline drinking | .49 | .06 | <.001 | [.37, .61] | .53 | .06 | <.001 | [.42, .64] |

| Lack of premeditation | .08 | .05 | .093 | [−.01, .180] | .11 | .05 | .033 | [.01, .21] |

| Context | .15 | .05 | .002 | [.05, .24] | −.01 | .06 | .86 | [−.13, .11] |

| Interactions | ||||||||

| Premeditation × Context | .12 | .04 | .002 | [.05, .20] | −.04 | .06 | .52 | [−.15, .08] |

| Lack of Perseverance Univariate Models | ||||||||

| Covariates and main effects | ||||||||

| Age | −.10 | .05 | .027 | [−.20, −.01] | −.12 | .05 | .013 | [−.22, −.03] |

| Sex | −.19 | .05 | <.001 | [−.29, −.08] | −.17 | .05 | .001 | [−.28, −.07] |

| Baseline drinking | .48 | .06 | <.001 | [.35, .60] | .53 | .06 | <.001 | [.42, .64] |

| Lack of perseverance | −.10 | .05 | .042 | [−.19, −.004] | −.08 | .05 | .10 | [−.17, .02] |

| Context | .17 | .05 | .001 | [.08, .27] | .01 | .06 | .84 | [−.10, .13] |

| Context quadratic | −.01 | .05 | .86 | [−.10, .09] | - | - | - | H- |

| Interactions | ||||||||

| Perseverance × Context | .04 | .04 | .32 | [−.04, .13] | .08 | .04 | .054 | [−.001, .17] |

| Perseverance × Context Quadratic | .11 | .04 | .006 | [.03, .20] | - | - | - | - |

Notes: UPPS-P = Negative Urgency, Premeditation (lack of), Perseverance (lack of), Sensation Seeking, and Positive Urgency Impulsive Behavior Scale; β = standardized beta; CI = confidence interval. Univariate models for each UPPS-P facet tested interactions between each impulsivity facet and high-arousal/low-arousal context factor scores. For each univariate model, the left columns correspond to high-arousal context analyses, and the right columns correspond to low-arousal analyses. “Context” refers to the high- and low-arousal context factor scores; quadratic interactions (and their lower order main effects) were retained only if significant at p < .05.

There was a quadratic interaction between lack of perseverance and the quadratic effect of high-arousal context (β = .11, SE = 0.04, p = .006, 95% CI [.03, .20]), and negative urgency and the quadratic effect of high-arousal context (β = .14, SE = 0.04, p = .001, 95% CI [.05, .22]). These interactions were included in each univariate model, respectively, to ensure that no linear interaction effects were impacted by the inclusion of quadratic interactions.

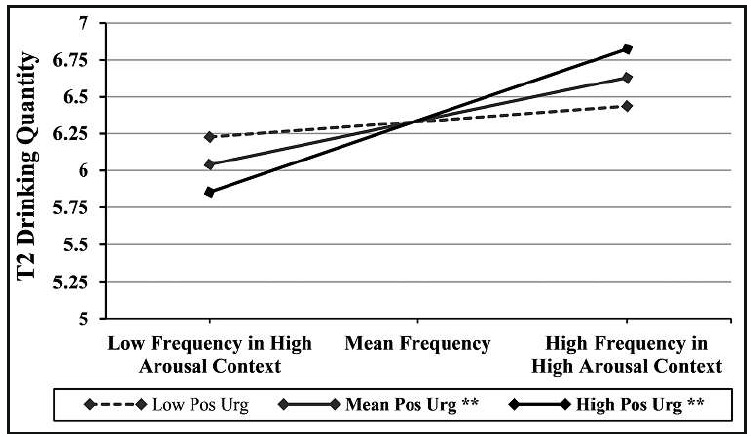

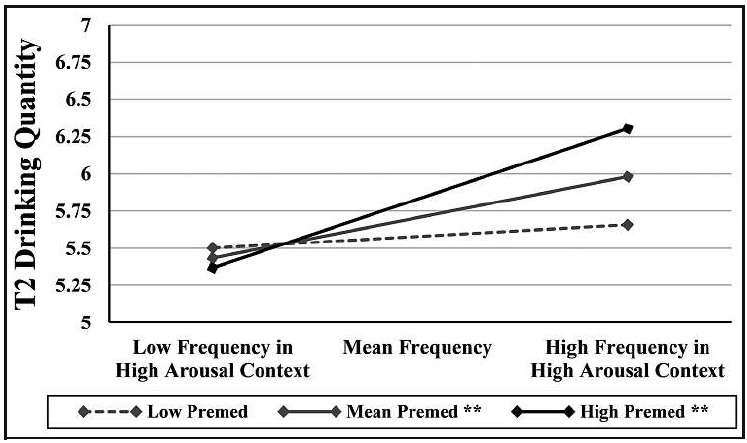

In univariate models, there were significant linear interactions between high-arousal context and both positive urgency (β = .12, SE = 0.04, p = .002, 95% CI [.05, .20]) and lack of premeditation (β = .12, SE = 0.04, p = .002, 95% CI [.04,.19]). Probing of these interactions suggested that more frequent drinking in high-arousal contexts was prospectively associated with heavier drinking for those at high (Positive Urgency β = .87, SE = 0.20, p < .001; Premeditation β = .85, SE = 0.19, p < .001) and mean (Positive Urgency β = .53, SE = 0.16, p = .001; Premeditation β = .49, SE = 0.16, p = .002), but not low (Positive Urgency β = .19, SE = 0.20, p = .33; Premeditation β = .14, SE = 0.19, p = .46) levels of positive urgency and lack of premeditation (Figures 1 and 2). There were no linear interactions between sensation seeking, negative urgency, or lack of perseverance and high-arousal contexts, nor any UPPS-P facets and low-arousal contexts.

Figure 1.

Positive urgency interaction. Pos. = positive; urg. = urgency; T2 = Time 2. **p < .01.

Figure 2.

Lack of premeditation interaction. Note: Premeditation (premed) is scored such that higher values are indicative of lack of premeditation; T2 = Time 2. **p < .01.

After we adjusted the false discovery rate (10 interactions), both the positive urgency and the lack of premeditation interactions remained significant.

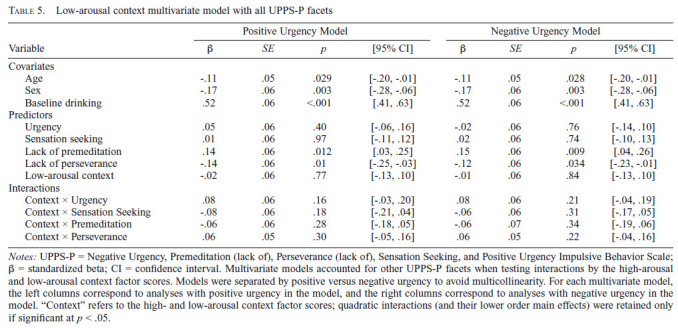

Multivariate models

Next, models were run with UPPS-P facets in the same model to test whether interactions with context persisted above and beyond other main effects and interactions. Two models (one for positive urgency and one for negative urgency) were run for each drinking context. Significant quadratic effects (and lower order main effects) were included in these models.

All covariate effects remained, and lack of premeditation prospectively predicted heavier drinking, whereas lack of perseverance prospectively predicted lighter drinking across models (Tables 4 and 5). In high-arousal context models, interaction between drinking context and both positive urgency (β = .10, p = .026) and lack of premeditation (PU Model β = .11, p = .018; NU Model β = .11, p = .011) remained significant at p < .05.

Table 4.

High-arousal context multivariate model with all UPPS-P facets

| Variable | Positive Urgency Model | Negative Urgency Model | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | SE | p | [95% CI] | β | SE | p | [95% CI] | |

| Covariates | ||||||||

| Age | −.10 | .05 | .037 | [−.19, −.01] | −.10 | .05 | .038 | [−.19, −.01] |

| Sex | −.19 | .06 | .001 | [−.30, −.08] | −.19 | .06 | .001 | [−.30, −.08] |

| Baseline drinking | .47 | .06 | <.001 | [.35, .59] | .47 | .06 | <.001 | [.35, .59] |

| Predictors | ||||||||

| Urgency | .03 | .06 | .54 | [−.07, .14] | −.02 | .06 | .74 | [−.14, .10] |

| Sensation Seeking | −.02 | .06 | .78 | [−.13, .10] | −.01 | .06 | .96 | [−.11, .11] |

| Lack of premeditation | .13 | .06 | .02 | [.02, .24] | .14 | .06 | .016 | [.03, .25] |

| Lack of perseverance | −.16 | .06 | .005 | [−.26, −.05] | −.14 | .06 | .015 | [−.25, −.03] |

| High-arousal context | .15 | .05 | .002 | [.05, .25] | .16 | .05 | .002 | [.06, .26] |

| High-arousal context quadratic | −.01 | .05 | .83 | [−.10, .08] | −.01 | .05 | .085 | [−.10, .08] |

| Interactions | ||||||||

| Context × Urgency | .10 | .04 | .026 | [.01, .18] | .02 | .06 | .78 | [−.09, .12] |

| Context Quadratic × Urgency | - | - | - | - | .13 | .04 | .003 | [.05, .21] |

| Context × Sensation Seeking | −.01 | .05 | .86 | [−.10, .08] | .02 | .04 | .60 | [−.06, .11] |

| Context × Premeditation | .11 | .05 | .018 | [.02, .19] | .11 | .04 | .011 | [.03, .20] |

| Context × Perseverance | −.03 | .05 | .58 | [−.13, .07] | .02 | .05 | .67 | [−.08, .13] |

| Context Quadratic × Perseverance | .11 | .04 | .014 | [.02, .19] | - | - | - | - |

Notes: UPPS-P = Negative Urgency, Premeditation (lack of), Perseverance (lack of), Sensation Seeking, and Positive Urgency Impulsive Behavior Scale; β = standardized beta; CI = confidence interval. Multivariate models accounted for other UPPS-P facets when testing interactions by the high-arousal and low-arousal context factor scores. Models were separated by positive versus negative urgency to avoid multicollinearity. For each multivariate model, the left columns correspond to analyses with positive urgency in the model, and the right columns correspond to analyses with negative urgency in the model. “Context” refers to the high- and low-arousal context factor scores; quadratic interactions (and their lower order main effects) were retained only if significant at p < .05.

Table 5.

Low-arousal context multivariate model with all UPPS-P facets

| Variable | Positive Urgency Model | Negative Urgency Model | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | SE | p | [95% CI] | β | SE | p | [95% CI] | |

| Covariates | ||||||||

| Age | −.11 | .05 | .029 | [−.20, −.01] | −.11 | .05 | .028 | [−.20, −.01] |

| Sex | −.17 | .06 | .003 | [−.28, −.06] | −.17 | .06 | .003 | [−.28, −.06] |

| Baseline drinking | .52 | .06 | <.001 | [.41, .63] | .52 | .06 | <.001 | [.41, .63] |

| Predictors | ||||||||

| Urgency | .05 | .06 | .40 | [−.06, .16] | −.02 | .06 | .76 | [−.14, .10] |

| Sensation seeking | .01 | .06 | .97 | [−.11, .12] | .02 | .06 | .74 | [−.10, .13] |

| Lack of premeditation | .14 | .06 | .012 | [.03, .25] | .15 | .06 | .009 | [.04, .26] |

| Lack of perseverance | −.14 | .06 | .01 | [−.25, −.03] | −.12 | .06 | .034 | [−.23, −.01] |

| Low-arousal context | −.02 | .06 | .77 | [−.13, .10] | −.01 | .06 | .84 | [−.13, .10] |

| Interactions | ||||||||

| Context × Urgency | .08 | .06 | .16 | [−.03, .20] | .08 | .06 | .21 | [−.04, .19] |

| Context × Sensation Seeking | −.08 | .06 | .18 | [−.21, .04] | −.06 | .06 | .31 | [−.17, .05] |

| Context × Premeditation | −.06 | .06 | .28 | [−.18, .05] | −.06 | .07 | .34 | [−.19, .06] |

| Context × Perseverance | .06 | .05 | .30 | [−.05, .16] | .06 | .05 | .22 | [−.04, .16] |

Notes: UPPS-P = Negative Urgency, Premeditation (lack of), Perseverance (lack of), Sensation Seeking, and Positive Urgency Impulsive Behavior Scale; β = standardized beta; CI = confidence interval. Multivariate models accounted for other UPPS-P facets when testing interactions by the high-arousal and low-arousal context factor scores. Models were separated by positive versus negative urgency to avoid multicollinearity. For each multivariate model, the left columns correspond to analyses with positive urgency in the model, and the right columns correspond to analyses with negative urgency in the model. “Context” refers to the high- and low-arousal context factor scores; quadratic interactions (and their lower order main effects) were retained only if significant at p < .05.

However, all multivariate interactions became nonsignificant after adjusting the false discovery rate (16 interactions). Consistent with the statistically significant effects in univariate models and effects that did not remain statistically significant with false discovery rate correction in the multivariate models, standardized effect sizes were slightly smaller in multivariate relative to univariate models (Premeditation univariate β = .12, multivariate β = .11; positive urgency univariate β = .12, multivariate β = .10).

Discussion

The current study is the first to test interactions between impulsivity and typical drinking contexts as prospective predictors of drinking behavior. Guided by Person-Environment Transactions Theory (Caspi & Roberts, 2001), we hypothesized that stimulating/high-arousal drinking contexts (e.g., at a party) would prospectively predict heavier drinking for individuals high in positive urgency and sensation seeking, and that sedating/low-arousal drinking contexts (e.g., in a restaurant) would prospectively predict heavier drinking for individuals high in negative urgency. Findings suggested that drinking context items broke down into high-arousal and low-arousal drinking contexts and that high-arousal drinking contexts were related with heavier drinking. In univariate models, main effects of high-arousal drinking contexts were moderated by positive urgency and a lack of premeditation, such that individuals at high and mean levels of these impulsivity facets drank more heavily the more frequently they drank in high-arousal drinking contexts.

These findings suggest that individuals who are high in positive urgency and lack premeditation/planning may gain more reward from high-arousal (but not low-arousal) contexts, thereby increasing the risk for heavier drinking. Specifically for positive urgency, it is possible that these individuals may feel a loss of control when drinking in highly stimulating contexts, predicting continued drinking with limited awareness of consumption and potential consequences. These experiences of low control coupled with high reward may reinforce drinking behavior, leading to a cycle of heavier future drinking. Impaired control over alcohol use (i.e., an irresistible urge and/or motivation to continue drinking), a proximal antecedent to heavier and problem drinking (Corbin et al., 2020; Leeman et al., 2009), is thought to be a mix of both low inhibitory control/high impulsivity and craving/wanting more alcohol (Leeman et al., 2009) and is highly related to impulsivity, particularly urgency facets (Vaughn et al., 2019; Wardell et al., 2015). Put in the context of the current study, drinking in a highly stimulating environment may provide rewarding memories associated with heavier drinking, thereby predicting habitual heavier drinking patterns, particularly for individuals high in positive urgency.

In contrast, potential mechanisms for the interaction between lack of premeditation and high-arousal contexts are less clear. Given that a lack of premeditation is thought to be a lower order indicator of lack of conscientiousness (Cyders et al., 2014), it is possible that individuals who lack premeditation may drink heavily with little regard for future consequences (low conscientiousness). This may be particularly true when these individuals drink in high-risk contexts that (a) have high-concentration alcohol readily available (i.e., tailgates) and (b) foster heavier drinking in short time spans (i.e., pre-gaming/drinking games).

It is important to note that, when tested in a multivariate model of UPPS-P facets, the p values for the lack of premeditation interaction (Positive Urgency model p = .018, Negative Urgency model p = .014) and positive urgency interaction (p = .026) did not remain significant after a false discovery correction. However, the effect sizes for these interactions (Premeditation univariate β = .12, multivariate β = .11; positive urgency univariate β = .12, multivariate β = .10) were quite similar. Thus, the shared variance between positive urgency and lack of premeditation somewhat reduced the unique prediction that was evident in the univariate models. Future research is needed to replicate these findings using larger samples and in higher risk populations (e.g., heavier drinkers and individuals experiencing alcohol-related problems).

The hypothesized effects for sensation seeking and negative urgency were not supported. This may be a function of our focus on drinking quantity. Some researchers consider sensation seeking to be distinct from impulsivity (Zuckerman, 2010), and sensation seeking may predict any drinking in high-arousal contexts (i.e., the act of going to a high-arousal drinking context may be thrilling), rather than drinking quantity. In contrast, negative urgency represents a strong risk factor for negative consequences and is driven by negative affect reduction (i.e., relaxation). Thus, it is possible that individuals high in negative urgency did not feel negative affect reduction in the current low-arousal drinking contexts examined in the current study.

Although we found only moderate support for the study hypotheses, the current findings have implications for preventive interventions. Focusing on the context in which individuals drink may be an effective way to reduce the risk for heavier drinking. Targeting high-arousal drinking contexts may be an effective strategy to reduce the risk for all drinkers, considering the strong main effect of drinking in high-arousal contexts; however, this strategy may be most effective for those high in positive urgency/lack of premeditation. Interventions may advocate for the use of protective behavioral strategies (e.g., alternate between alcoholic and nonalcoholic drinks), a consistent predictor of lighter drinking (Martens et al., 2004) when drinking in high-arousal contexts, particularly for those high in positive urgency/lack of premeditation.

Although the current study has important implications, the findings must be interpreted in the light of limitations. The current study used an aggregate index of typical drinking quantity, rather than drinking quantity in stimulating and sedating contexts, and thus future research assessing typical drinking quantity within specific drinking contexts is needed. The current study also predicted outcomes across a 1-year period rather than using a daily diary design, which is needed to test the dynamic, momentary mechanisms through which impulsivity contributes to heavy drinking in specific contexts. Furthermore, since the current study used data from only two time points, it was not possible to disentangle between-person from within-person longitudinal processes. Finally, participants were social drinkers and ages 21–25, and replication in higher risk drinkers as well as age-heterogeneous samples are needed.

Despite these limitations, the current study is the first to test theoretically interesting interactions between impulsivity and drinking contexts, finding that individuals who lack premeditation and who are higher in positive urgency drink more heavily the more frequently they drink in high-arousal contexts—although these effects did not remain statistically significant when other UPPS-P interactions with drinking context were accounted for. Future research using intensive longitudinal designs (e.g., Ecological Momentary Assessment) is needed, as are studies designed to understand potential mechanisms (e.g., expectancies, motives, craving) through which impulsivity facets contribute to heavier drinking in specific drinking contexts.

Conflict-of-Interest Statement

Authors report no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

This study was supported by National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Grant R01 AA021148 to William R. Corbin. No author has changed affiliations since the time of the study. A portion of the current findings was presented at the 2020 Collaborative Perspectives on Addiction Meeting.

References

- Aiken L. S., West S. G., Reno R. R. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson K. G., Smith G. T., Fischer S. F. Women and acquired preparedness: Personality and learning implications for alcohol use. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2003;64:384–392. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2003.64.384. doi:10.15288/jsa.2003.64.384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asparouhov T., Muthén B. Exploratory structural equation modeling. Structural Equation Modeling. 2009;16:397–438. doi:10.1080/10705510903008204. [Google Scholar]

- Barnett N. P., Clerkin E. M., Wood M., Monti P. M., O'Leary Tevyaw T., Corriveau D., Kahler C. W. Description and predictors of positive and negative alcohol-related consequences in the first year of college. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2014;75:103–114. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2014.75.103. doi:10.15288/jsad.2014.75.103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belzak W. C. M., Bauer D. J. Interaction effects may actually be nonlinear effects in disguise: A review of the problem and potential solutions. Addictive Behaviors. 2019;94:99–108. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2018.09.018. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2018.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini Y., Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: A practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. Series A, (Statistics in Society) 1995;57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- Berey B. L., Leeman R. F., Chavarria J., King A. C. Relationships between generalized impulsivity and subjective stimulant and sedative responses following alcohol administration. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2019;33:616–625. doi: 10.1037/adb0000512. doi:10.1037/adb0000512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey K. B., Carey M. P., Maisto S. A., Henson J. M. Temporal stability of the timeline followback interview for alcohol and drug use with psychiatric outpatients. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2004;65:774–781. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2004.65.774. doi:10.15288/jsa.2004.65.774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A., Roberts B. W. Personality development across the life course: The argument for change and continuity. Psychological Inquiry. 2001;12:49–66. doi:10.1207/S15327965PLI1202_01. [Google Scholar]

- Collins R. L., Parks G. A., Marlatt G. A. Social determinants of alcohol consumption: The effects of social interaction and model status on the self-administration of alcohol. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1985;53:189–200. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.53.2.189. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.53.2.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comrey A. L., Lee H. B. A first course in factor analysis. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Psychology Press; 1992. Interpretation and application of factor analytic results. [Google Scholar]

- Corbin W. R., Berey B. L., Waddell J. T., Leeman R. F. Relations between acute effects of alcohol on response inhibition, impaired control over alcohol use, and alcohol related problems. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2020;44:1123–1131. doi: 10.1111/acer.14322. doi:10.1111/acer.14322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbin W. R., Scott C., Boyd S. J., Menary K. R., Enders C. K. Contextual influences on subjective and behavioral responses to alcohol. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2015;23:59–70. doi: 10.1037/a0038760. doi:10.1037/a0038760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coskunpinar A., Dir A. L., Cyders M. A. Multidimensionality in impulsivity and alcohol use: A meta-analysis using the UPPS model of impulsivity. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2013;37:1441–1450. doi: 10.1111/acer.12131. doi:10.1111/acer.12131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox M. J., Sewell K., Egan K. L., Baird S., Eby C., Ellis K., Kuteh J. A systematic review of high-risk environmental circumstances for adolescent drinking. Journal of Substance Use. 2019;24:465–474. doi:10.1080/14659891.2019.1620890. [Google Scholar]

- Cyders M. A., Littlefield A. K., Coffey S., Karyadi K. A. Examination of a short English version of the UPPS-P Impulsive Behavior Scale. Addictive Behaviors. 2014;39:1372–1376. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.02.013. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cyders M. A., Smith G. T. Emotion-based dispositions to rash action: Positive and negative urgency. Psychological Bulletin. 2008;134:807–828. doi: 10.1037/a0013341. doi:10.1037/a0013341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dick D. M., Smith G., Olausson P., Mitchell S. H., Leeman R. F., O'Malley S. S., Sher K. Understanding the construct of impulsivity and its relationship to alcohol use disorders. Addiction Biology. 2010;15:217–226. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2009.00190.x. doi:10.1111/j.1369-1600.2009.00190.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairbairn C. E., Sayette M. A. The effect of alcohol on emotional inertia: A test of alcohol myopia. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2013;122:770–781. doi: 10.1037/a0032980. doi:10.1037/a0032980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henges A. L., Marczinski C. A. Impulsivity and alcohol consumption in young social drinkers. Addictive Behaviors. 2012;37:217–220. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.09.013. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L., Bentler P. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling. 1999;6:1–55. doi:10.1080/10705519909540118. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson K. M. Heavy episodic drinking: Determining the predictive utility of five or more drinks. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2008;22:68–77. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.22.1.68. doi:10.1037/0893-164X.22.1.68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jöreskog K. G., Sörbom D. LISREL 7: A guide to the program and applications. SPSS; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Kirkpatrick M. G., de Wit H. In the company of others: Social factors alter acute alcohol effects. Psychopharmacology. 2013;230:215–226. doi: 10.1007/s00213-013-3147-0. doi:10.1007/s00213-013-3147-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leeman R. F., Beseler C. L., Helms C. M., Patock-Peckham J. A., Wakeling V. A., Kahler C. W. A brief, critical review of research on impaired control over alcohol use and suggestions for future studies. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2014;38:301–308. doi: 10.1111/acer.12269. doi:10.1111/acer.12269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leeman R. F., Toll B. A., Taylor L. A., Volpicelli J. R. Alcohol-induced disinhibition expectancies and impaired control as prospective predictors of problem drinking in undergraduates. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2009;23:553–563. doi: 10.1037/a0017129. doi:10.1037/a0017129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynam D., Smith G. T., Cyders M. A., Fischer S., Whiteside S. A. The UPPS-P: A multidimensional measure of risk for impulsive behavior. 2007 Unpublished technical report. [Google Scholar]

- Magid V., MacLean M. G., Colder C. R. Differentiating between sensation seeking and impulsivity through their mediated relations with alcohol use and problems. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:2046–2061. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.01.015. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh H. W., Guo J., Dicke T., Parker P. D., Craven R. G. Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), exploratory structural equation modeling (ESEM) and set-ESEM: Optimal balance between goodness of fit and parsimony. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 2020;55:102–119. doi: 10.1080/00273171.2019.1602503. doi:10.1080/00273171.2019.1602503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martens M. P., Taylor K. K., Damann K. M., Page J. C., Mowry E. S., Cimini M. D. Protective behavioral strategies when drinking alcohol and their relationship to negative alcohol-related consequences in college students. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2004;18:390–393. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.18.4.390. doi:10.1037/0893-164X.18.4.390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy D. M., Kroll L. S., Smith G. T. Integrating disinhibition and learning risk for alcohol use. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2001;9:389–398. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.9.4.389. doi:10.1037/1064-1297.9.4.389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarty K. N., Morris D. H., Hatz L. E., McCarthy D. M. Differential associations of UPPS-P impulsivity traits with alcohol problems. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2017;78:617–622. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2017.78.617. doi:10.15288/jsad.2017.78.617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moeller F. G., Barratt E. S., Dougherty D. M., Schmitz J. M., Swann A. C. Psychiatric aspects of impulsivity. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2001;158:1783–1793. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.11.1783. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.158.11.1783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moser K., Pearson M. R., Hustad J. T., Borsari B. Drinking games, tailgating, and pregaming: Precollege predictors of risky college drinking. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2014;40:367–373. doi: 10.3109/00952990.2014.936443. doi:10.3109/00952990.2014.936443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Hare T. Measuring excessive alcohol use in college drinking contexts: The Drinking Context Scale. Addictive Behaviors. 1997;22:469–477. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(96)00050-0. doi:10.1016/s0306-4603(96)00050-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohsenow D. J., Howland J., Minsky S. J., Greece J., Almeida A., Roehrs T. A. The Acute Hangover Scale: A new measure of immediate hangover symptoms. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:1314–1320. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.10.001. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayette M. A., Creswell K. G., Dimoff J. D., Fairbairn C. E., Cohn J. F., Heckman B. W., Moreland R. L. Alcohol and group formation: A multimodal investigation of the effects of alcohol on emotion and social bonding. Psychological Science. 2012;23:869–878. doi: 10.1177/0956797611435134. doi:10.1177/0956797611435134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott C., Corbin W. R. Influence of sensation seeking on response to alcohol versus placebo: Implications for the acquired preparedness model. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2014;75:136–144. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2014.75.136. doi:10.15288/jsad.2014.75.136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Settles R. F., Cyders M., Smith G. T. Longitudinal validation of the acquired preparedness model of drinking risk. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2010;24:198–208. doi: 10.1037/a0017631. doi:10.1037/a0017631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith G. T., Anderson K. G. Personality and learning factors combine to create risk for adolescent problem drinking: A model and suggestions for intervention. In: Monti P. M., Colby S. M., O'Leary T. A., editors. Adolescents, alcohol, and substance abuse: Reaching teens through brief interventions. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2001. pp. 109–141. [Google Scholar]

- Smith G. T., Cyders M. A. Integrating affect and impulsivity: The role of positive and negative urgency in substance use risk. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2016;163(Supplement 1):S3–S12. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.08.038. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.08.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith G. T., Guller L., Zapolski T. C. A comparison of two models of urgency: Urgency predicts both rash action and depression in youth. Clinical Psychological Science. 2013;1:266–275. doi: 10.1177/2167702612470647. doi:10.1177/2167702612470647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobell L. C., Sobell M. B. Measuring alcohol consumption. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; 1992. Timeline follow-back; pp. 41–72. [Google Scholar]

- Stacy A. W., Newcomb M. D., Bentler P. M. Cognitive motivations and sensation seeking as long-term predictors of drinking problems. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 1993;12:1–24. doi:10.1521/jscp.1993.12.1.1. [Google Scholar]

- Stanesby O., Labhart F., Dietze P., Wright C. J. C., Kuntsche E. The contexts of heavy drinking: A systematic review of the combinations of context-related factors associated with heavy drinking occasions. PLoS One. 2019;14:e0218465. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0218465. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0218465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick B. G., Fidell L. S. Using multivariate statistics, fourth edition. Needham Heights, MA: Allyn & Bacon; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Vaughan C. L., Stangl B. L., Schwandt M. L., Corey K. M., Hendershot C. S., Ramchandani V. A. The relationship between impaired control, impulsivity, and alcohol self-administration in nondependent drinkers. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2019;27:236–246. doi: 10.1037/pha0000247. doi:10.1037/pha0000247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waddell J.T., Elam K.K., Chassin L. Multidimensional Impulsive Personality Traits Mediate the Effect of Parent Substance Use Disorder on Adolescent Alcohol and Cannabis Use. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2022 doi: 10.1007/s10964-021-01556-3. doi:10.1007/s10964-021-01556-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waddell J. T., Sternberg A., Grimm K. J., Chassin L. Do alcohol consequences serve as teachable moments? A test of between-and within-person reciprocal effects from college age to adulthood. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2021a;82:647–658. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2021.82.647. doi:10.15288/jsad.2021.82.647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waddell J. T., Blake A. J., Chassin L. Relations between impulsive personality traits, alcohol and cannabis co-use, and negative alcohol consequences: A test of cognitive and behavioral mediators. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2021b;225:108780. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2021.108780. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2021.108780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waddell J. T., Corbin W. R., Leeman R. F. Differential effects of UPPS-P impulsivity on subjective alcohol response and craving: An experimental test of acquired preparedness. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2021c doi: 10.1037/pha0000524. Advance online publication. doi:10.1037/pha0000524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waddell J. T., Corbin W. R., Marohnic S. D. Putting things in context: Longitudinal relations between drinking contexts, drinking motives, and negative alcohol consequences. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2021d;35:148–159. doi: 10.1037/adb0000653. doi:10.1037/adb0000653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wardell J. D., Quilty L. C., Hendershot C. S. Alcohol sensitivity moderates the indirect associations between impulsive traits, impaired control over drinking, and drinking outcomes. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2015;76:278–286. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2015.76.278. doi:10.15288/jsad.2015.76.278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wardell J. D., Read J. P., Colder C. R., Merrill J. E. Positive alcohol expectancies mediate the influence of the behavioral activation system on alcohol use: A prospective path analysis. Addictive Behaviors. 2012;37:435–443. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.12.004. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wetherill R. R., Fromme K. Alcohol induced blackouts: A review of recent clinical research with practical implications and recommendations for future studies. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2016;40:922–935. doi: 10.1111/acer.13051. doi:10.1111/acer.13051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiteside S. P., Lynam D. R. The Five Factor Model and impulsivity: Using a structural model of personality to understand impulsivity. Personality and Individual Differences. 2001;30:669–689. doi:10.1016/S0191-8869(00)00064-7. [Google Scholar]

- Zuckerman M.Weiner I. B., Craighead W. E., editors. Sensation seeking. Corsini Encyclopedia of Psychology. 2010. doi:10.1002/9780470479216.corpsy0843.