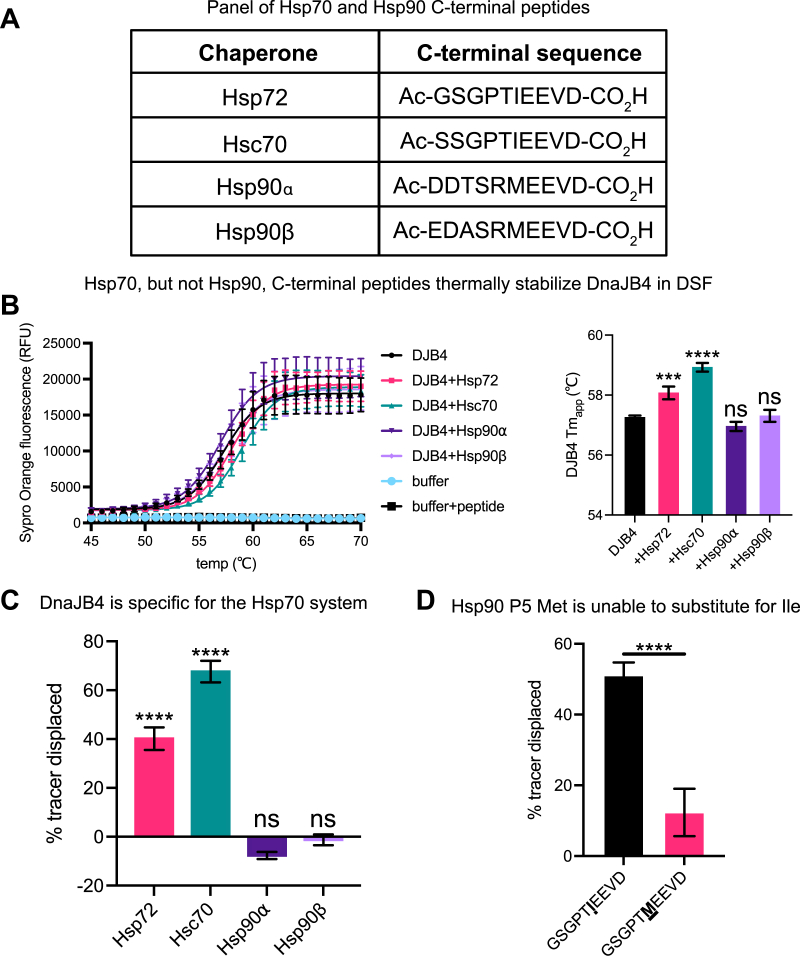

Figure 3.

DnaJB4 binds Hsp70’s IEEVD motif but not the closely related MEEVD from Hsp90.A, table listing the sequences of chaperone C-terminal peptides used in this study. B, differential scanning fluorimetry melting curves and apparent melting temperatures (Tm,app) of 5 μM DnaJB4 in the presence of either a dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) control or various chaperone peptides (100 μM). Temperature-dependent unfolding was monitored by Sypro Orange fluorescence. The melting curves represent the mean Sypro Orange fluorescence ± SD (n = 4). Buffer alone and buffer + peptide samples were used as negative controls. The calculated DnaJB4 Tm,app values are mean ± SD (n = 4). Statistics were performed using unpaired Student’s t test (∗∗∗p < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001, ns, not significant compared with DMSO control). C, FP experiment showing displacement of Hsp72 probe from DnaJB4 by various chaperone competitor peptides. Graph shows the mean tracer displacement relative to a DMSO control ± SD (n = 4). Statistics were performed using unpaired Student’s t test (∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001, ns, not significant compared with DMSO control). D, competition FP experiment comparing WT Hsp72 to a mutant in which the P5 Ile was replaced by Met. Graph shows the mean tracer displacement relative to DMSO control ± SD (n = 4). Statistics were performed using unpaired Student’s t test (∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001 compared with WT control).