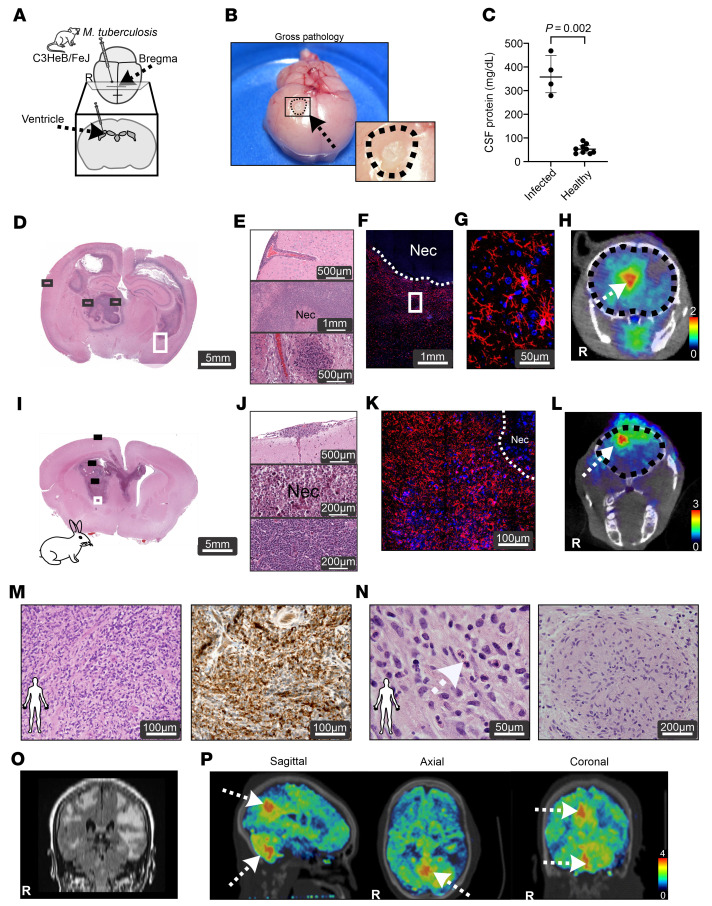

Figure 2. Animal models of TB meningitis recapitulate human disease.

Mice (A–H), rabbits (I–L), and humans (M–P). (A) Schematic of brain infection of mice with live M. tuberculosis. Two weeks after infection, brain lesions were noted on gross pathology (B) with high protein in the CSF (n = 4–9 animals/group) (C). Histopathology from the brains of infected mice (D–G) and rabbits (I–K) demonstrates TB lesions with inflammatory cells. Panels E and J show meningitis (upper panels), necrotizing tuberculomas (middle panels), and nonnecrotizing tuberculomas (lower panels). Immunohistochemistry demonstrates microglia (Iba-1 stain in red and DAPI nuclear stain in blue) in brains from infected mice (F and G) and rabbits (K). 18F-FDG uptake is noted in the brain lesions on PET/CT images (arrows) from infected mice (H) and rabbits (L). Areas of nonspecific PET uptake were also noted extracranially. (M and N) Histology from brain lesion biopsies from 2 patients with TB meningitis (subjects 3 and 5, Supplemental Table 1) CD68+ cells (right, panel [M]) and multinucleated giant cells (left panel [N], white arrow). (O) MRI from a 67-year-old female with TB meningitis (subject 3, Supplemental Table 1) demonstrating focal FLAIR hyperintensities and 18F-FDG uptake (arrows) noted on PET/CT images (P). Coronal PET images are presented as standardized uptake values (SUV). High-power views (D, E, I, J, M, and N) are shown in Supplemental Figures 1 and 3, respectively. Data are represented as median ± IQR. Statistical comparisons were performed using a 2-tailed Mann-Whitney-Wilcoxon test (B). R, right; Nec, necrotizing.