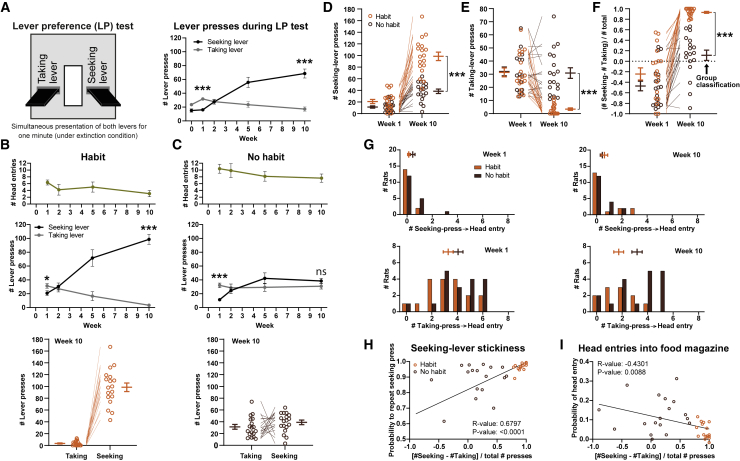

Figure 2.

A novel preference test to measure the development of habits

(A) Habit formation was tested by presenting both levers simultaneously for 1 min under extinction conditions (left). In week 1 of VI60:FR1 seeking-taking training, rats preferentially pressed the taking lever, but by week 10, preference had shifted to the seeking lever (right).

(B) In the habit group, the number of food-magazine head entries remained stable (top) across weeks, but rats switched from a taking- to a strong seeking-lever preference (middle) and exhibited more seeking than taking presses in week 10 (bottom).

(C) Food-magazine head entries remained stable in the no-habit group (top), but rats switched from a taking-lever preference to no preference (middle) and exhibited no significant difference between seeking and taking presses in week 10 (bottom).

(D and E) Habitual rats performed more seeking-lever presses (D) and fewer taking-lever presses (E) than non-habitual rats in week 10, but not in week 1.

(F) The seeking-taking preference index demonstrates a higher seeking-lever preference in habitual rats compared to non-habitual rats in week 10, but not in week 1.

(G) The conditioning “logic” translated from training to preference test: food-magazine head entries were executed more frequently after taking-lever presses than after seeking-lever presses, both in habitual and non-habitual rats. Histogrammed data with mean ± SEM shown separately.

(H and I) Linear regression analyses demonstrate associations of the seeking-lever index with other habit-like behavior during the preference test, i.e., (H) a positive correlation with seeking-lever stickiness and (I) a negative correlation with food-magazine head-entry probability. Data are mean ± SEM, in some panels combined with individual animals (open circles). ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗∗p < 0.001.

See also Figures S2 and S3.