Summary

The daily rhythm of plasma melatonin concentrations is typically unimodal, with one broad peak during the circadian night and near-undetectable levels during the circadian day. Light at night acutely suppresses melatonin secretion and phase shifts its endogenous circadian rhythm. In contrast, exposure to darkness during the circadian day has not generally been reported to increase circulating melatonin concentrations acutely. Here, in a highly-controlled simulated night shift protocol with 12-h inverted behavioral/environmental cycles, we unexpectedly found that circulating melatonin levels were significantly increased during daytime sleep (P<0.0001). This resulted in a secondary melatonin peak during the circadian day in addition to the primary peak during the circadian night, when sleep occurred during the circadian day following an overnight shift. This distinctive diurnal melatonin rhythm with antiphasic peaks could not be readily anticipated from the behavioral/environmental factors in the protocol (e.g., light exposure, posture, diet, activity) or from current mathematical model simulations of circadian pacemaker output. The observation therefore challenges our current understanding of underlying physiological mechanisms that regulate melatonin secretion. Interestingly, the increase in melatonin concentration observed during daytime sleep was positively correlated with the change in timing of melatonin nighttime peak (P=0.0015), but not with the degree of light-induced melatonin suppression during nighttime wakefulness (P=0.92). Both the increase in daytime melatonin concentrations and the change in the timing of the nighttime peak became larger after repeated exposure to simulated night shifts (P=0.009 and P=0.0001, respectively). Furthermore, we found that melatonin secretion during daytime sleep was positively associated with an increase in 24-h glucose and insulin levels during the night shift protocol (P=0.014 and P=0.027, respectively). Future studies are needed to elucidate the key factor(s) driving the unexpected daytime melatonin secretion and the melatonin rhythm with antiphasic peaks during shifted sleep/wake schedules, the underlying mechanisms of their relationship with glucose metabolism, and the relevance for diabetes risk among shift workers.

Keywords: Melatonin, circadian pacemaker, night shift, glucose metabolism

INTRODUCTION

Based on a synthesis of the melatonin literature, a long-standing paradigm exists for understanding melatonin regulation. The endogenous circadian rhythm of plasma melatonin is inherently unimodal with a nocturnal peak, with melatonin rapidly rising in the circadian evening and falling in the circadian morning [1, 2]. This rise at night can be suppressed by light exposure, meaning dim conditions are needed to measure the endogenous rise [3, 4]. Furthermore, according to the commonly-accepted understanding of melatonin regulation, darkness alone does not stimulate melatonin production, but rather is permissive for plasma melatonin to rise under circadian control during the circadian night [5–7]. Also, it is generally accepted that the melatonin rhythm in humans requires a minimum of 5–7 days to re-entrain to a 12-hour shift in the light-dark cycle [8], except in case of exposure to a very strong photic resetting stimulus, e.g., multiple successive nights of long (6–8 h) and very bright (~10,000 lux) light exposure (i.e., ‘type 0’ resetting), in which case it still takes at least three days [4, 9]. This current understanding of melatonin regulation is embodied in mathematical models that have been developed to predict melatonin profiles and to extract information on circadian phase [10–13]. Since melatonin is used as the gold-standard marker for circadian phase, this paradigm is of central importance to the entire research and clinical sleep and circadian field.

Unconventional melatonin profiles, which do not follow a nocturnal unimodal profile, have been reported sporadically before. Elevated melatonin levels in the circadian afternoon have been observed in healthy participants after acutely advancing the sleep episode by 8 hours under highly controlled laboratory conditions [14] or a short nap [15]. Because these phenomena generally occurred with only a modest melatonin elevation, they did not receive much attention or influence the prevailing paradigm. However, because these isolated observations deviate from our current model of melatonin regulation, they indicate that there might be an unknown mechanism underlying the regulation of melatonin secretion.

Here, we unexpectedly observed a surprising daytime melatonin increase after abruptly inverting the sleep-wake cycle (simulated night-shift conditions), i.e., deviating from the conventional paradigm. Given that the inhibition of melatonin production during the circadian day is dependent on GABAergic inhibition by the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN), we tested whether the daytime rise in melatonin would correlate with larger suppression or change in timing of the circadian nighttime peak during simulated night work, since both measures are potential indicators for decreased robustness of circadian oscillators [16, 17]. Furthermore, given evidence that sleep can directly impact SCN neural activity in animal models [18], and that sympathetic nervous system activity can influence melatonin production [19], we also investigated the relationship between the melatonin pattern with sleep parameters and measures of sympathetic nervous system activity. Finally, given the important role of melatonin on glucose metabolism[20], we further tested whether the daytime melatonin increase was linked to the well-known negative effects of circadian misalignment on glucose levels [21].

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Other aspects of this protocol, designed to test independent hypotheses, have been published [22–31]. Method details see Supporting Methods.

Experimental Design.

Fourteen healthy participants [mean age ± SD (range), 28 ± 9 y (20–49 y); BMI, 25.4 ± 2.6 kg/m2 (21–29.5 kg/m2); six women] completed two 8-day laboratory protocols, according to a randomized, cross-over design (Figure 1). Both protocols started with 3 days of adaptation, during which the participants maintained a regular sleep-wake schedule with a 16-h wake episode under a 450-lux light exposure and an 8-h sleep opportunity in darkness, to enhance circadian entrainment. The day-shift protocol maintained this schedule throughout the protocol but lowered the light level to ~4 lux on the transition day (Day 4) and to 90 lux during the wake episodes on the remaining test days to simulate typical room light intensity. The night shift protocol introduced a rapid 12-h shift of the environmental/behavioral cycle on the transition day (Day 4) under dim light (~4 lux), and continued this inverted schedule, but with 90-lux light exposure during waking hours for the remaining three test days—as is typical for many shift workers.

Figure 1.

The day shift protocol (Top) and night shift protocol (Bottom), as part of the randomized, cross-over design. 24-h melatonin profiles were assessed on days 5 and 7 in the day shift protocol and across days 5/6 and 7/8 in the night shift protocol (orange and purple dash lines, as test day 1 and test day 3, respectively). In the night shift protocol, melatonin profiles under dim light on day 4 were also assessed (brown dotted line). Light levels indicated are in the horizontal angle of gaze. Green boxes represent meals (wide) and snacks (narrow).

Data Analysis and Statistics.

We conducted linear mixed-effect models to test, on the group-level, whether melatonin AUC during 11AM-7PM were significantly different between the night-shift and day-shift protocols. The outcome was normalized by using an average of each participant’s levels measured in the day-shift protocol to minimize any effect of interindividual differences in baseline melatonin levels. In this model, shift, day, and interaction of shift and day were used as fixed effects, and participant as random effects including random intercepts and slopes for shift. The effect sizes of the fixed effects were estimated as differences of least squares means. To determine, on the individual level, how many individuals showed a significant elevation of plasma melatonin concentration during the two daytime sleep episodes in the night shift protocol, we calculated upper bound of the 95% confidence interval (CI) as each individual’s threshold based on the values of melatonin levels between 11AM-7PM of both test days in day shift protocol. If average melatonin levels between 11AM-7PM on both test days in night shift protocol (daytime sleep episode) was greater than the threshold, we considered this individual to have a significant melatonin elevation during daytime sleep.

To examine whether melatonin increase during daytime sleep is associated with changes in peak and peak timing of melatonin rhythms, we used the linear mixed model with Daytime Melatonin Increase (details see Supplemental Methods) as the outcome, participants as random effect, Change in Peak Time and Suppression of Peak as fixed effects, and an interaction term of the two fixed effects. The associations of percentage changes in 24-h glucose AUC or 24-h insulin AUC with the inter-individual differences in the melatonin response to the night shift condition were tested by the linear mixed model with Daytime Sleep Melatonin Increase, Change in Peak Time or Suppression of Peak as fixed effects, participants as random effect. Statistical tests were performed in JMP®, Version Pro14, with SAS OnDemand Integration (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, 1989–2007). An analysis of residuals was conducted to determine model fit. A 2-sided p<0.05 was considered significant. Data are presented as mean ± SEM unless otherwise indicated.

RESULTS

Melatonin unexpectedly increased in participants during daytime sleep on the simulated night-shift protocol.

A striking observation was a significantly higher 8-h melatonin area under the curve (AUC) during the daytime sleep episodes (11am-7pm) on the simulated night-shift protocol as compared to the melatonin AUC in the same 8-h daytime window on the day-shift protocol. Overall, the 8-h melatonin AUC was significantly and 2.91 ± 0.35 times higher (shift [night-shift vs. day-shift]: P=0.006, Figure 2B), equivalent to 14 pg*h/ml increase, on the night-shift protocol than that on the day-shift protocol. A longer duration of exposure to the night-shift protocol augmented the daytime increase in melatonin AUC by 1.89 ± 0.21 times (test days 3 vs. 1 on night shift: adj.P=0.002, 10 pg*h/ml, Supplemental Fig. 1). Despite the highly significant increases at the group level, there were large interindividual variations in the magnitude of this change in melatonin AUC (Supplemental Fig. 1; test day 1: range −48% to 450%, coefficients of variation[CV] 53%; test day 3: range 28% to 465%, CV 45%). All except one daytime sleep episode had higher melatonin levels than during daytime wake (25 out of 26 observations on both test days 1 and 3, χ2 (1, N = 26) = 22.1, p < 0.0001; two of the 28 test days were excluded due to missing data points). Specifically, on test day 3, 8 out of the 12 observations had over 3-fold increase in melatonin levels during daytime sleep as compared to daytime wake (Supplemental Fig. 1). Indeed, in eleven out of the fourteen participants, the average melatonin levels during the daytime sleep under the night shifts was higher than the upper bound of the 95% CI of that during the daytime wake episode under the day shifts, indicating a significant melatonin increase.

Figure 2.

Melatonin profiles on test day 1 and test day 3 in day shift (black) and night shift (red) protocols. (A) Representative melatonin pattern with antiphasic daytime and nighttime peaks from one participant. (B) Melatonin profiles of group average. Gray bar and red bar above the x-axis represent sleep opportunity during the day shift and the night shift, respectively. Re-plotted melatonin profiles are presented with dashed line. The insets on the top right in (B) show the average melatonin levels during the 8-h daytime windows that were compared between the two protocols. P values, statistical significance for the effect of shift (i.e., simulated day shift vs. night shift). Data are represented as mean ± SEM.

We also estimated the fitted daytime peak and peak timing of the melatonin rhythm by ensemble empirical mode decomposition (EEMD, see Supporting Methods) for each individual on each test day (n=14 participants, with two of the twenty-eight test days excluded due to missing data points). Eleven out of the fourteen participants had at least one test day with a fitted daytime peak that exceeded 15% of the fitted nighttime peak under the night-shift protocol (Supplemental Table 1), confirming a melatonin pattern with antiphasic peaks (e.g., MSW06, Fig. 2A). On average, the fitted daytime peak was 34.9% (95% CI 13.7%—56.1%) and 52.4% (95% CI 21.8%—83.0%) of the fitted nighttime peak on test days 1 and 3, respectively. The timing of the fitted daytime peak was 12.0 h (95% CI 10.6—13.4 h) and 13.6 h (95% CI 12.4—14.8 h) from the fitted nighttime peak on test days 1 and 3, respectively. Eight of the sixteen prominent daytime peaks (>15% of nighttime peak) occurred during the 1st daytime sleep episode, which was preceded only by prior dim light exposure during transition day.

Large interindividual differences in nocturnal peak of the melatonin rhythm on night-shift protocol.

As compared to the day-shift protocol, the EMD-fitted nighttime melatonin peak during the night-shift protocol was suppressed by 60.3 ± 0.1% (shift: P<0.0001), without significant difference between test days 1 and 3 (test days 1 vs. 3: adj.P = 0.32) (Figure 2B); and the nighttime peak was delayed by 1.9 ± 0.4 h in the night-shift protocol (shift: P < 0.0001), with an estimated delay of 0.5 ± 0.3 h on test day 1 (1 participant excluded due to lack of nighttime peak) and a delay of 3.3 ± 0.3 h on test day 3 (2 participants excluded due to incomplete data for fitting; test days 1 vs. 3: adj.P < 0.0001). However, the individual-level melatonin profiles showed high interindividual variability in response to the 90-lux night light exposure (Figure 3A). The individual suppression of the fitted nighttime melatonin peak ranged from 5% to 94% for test day 1 and from 14% to 96% for test day 3, with CV of 50% and 43%, respectively. The individual change in time of the fitted nighttime peak ranged from −2.6 to 9.8 h for test day 1 and 1.4 to 6.7h for test day 3, with CV of 286% and 55%, respectively (Figure 3B). In one participant, available data suggest that the daytime melatonin elevation in combination with a prominent nighttime light-induced suppression resulted in an inverted melatonin pattern with a nearly 12-h difference in the timing of the observed (damped) peak (e.g., MSW14, Supplemental Fig. 4).

Figure 3.

Individual melatonin profiles in response to simulated night shift conditions. Each individual melatonin profile is labeled with different colors and symbols and kept the same between test day 1 (left) and test day 3 (right) in day shift and night shift protocols. (A) Re-plotted melatonin profiles are presented with dashed line. The symbols above the line profiles mark the peak timing of the corresponding individual melatonin profiles. The size of each symbol represents the magnitude of the peak. Dark gray bar, sleep opportunity in the darkness (0 lux). Light gray bar, wakefulness under dim light condition (4 lux). (B) Rayleigh plots showing the changes in the parameters of melatonin rhythm under night shift protocol as compared to the day shift protocol. The radial length and phase angle of each symbol represents the magnitudes of melatonin suppression (note: shorter radial length represents stronger suppression) and the change in peak timing, respectively, and the black arrow the aggregate phase vector. Note the blue solid circle represents MSW14, in which a nocturnal melatonin peak was absent in test day 1, and the daytime peak at ~2PM was identified as the primary peak. It was excluded from the subsequent analysis involving change in timing of nighttime melatonin peak.

We used an established limit-cycle oscillator of the human circadian system with a component for simulating melatonin curves [12, 32] to predict the expected response to the day-shift and night-shift protocols (see Supporting Methods). The model’s assumptions are based on the existing paradigm for melatonin regulation and has been fitted to group-level and individual-level data in prior work [12]. We found that the model predicted exclusively unimodal melatonin profiles under both day-shift and night-shift conditions, with gradual adaptation to the night-shift protocol (0.8 h phase shift on day 1, 3.3 h phase shift on day 3). The model did not account for the antiphasic or inverted patterns we observed, either at the group or individual level, even after allowing model parameters to be refit to our data (Supplemental Fig. 5A–B). The latter improved predictions of peak timing, but still only resulted in unimodal melatonin patterns. We investigated whether the observed melatonin rhythm with antiphasic peaks could be explained by sleep-based promotion of melatonin synthesis by adding one novel parameter to the model. With this one additional factor, the model was able to reproduce the observed antiphasic melatonin peaks at both the group and individual levels (Supplemental Fig. 5C–F).

Hourly melatonin increase during daytime sleep was negatively correlated with slow-wave sleep, but not with measures of sympathetic nervous system activity.

To examine a possible role of sleep in the melatonin rise during the daytime sleep episode, we examined the correlation between the daytime melatonin increase and variables of sleep architecture assessed objectively using polysomnography (PSG). The quantity and quality of daytime sleep (including sleep efficiency, percentage of stage 1 sleep [N1%], stage 2 sleep [N2%], slow-wave sleep [SWS%], and rapid eye movement sleep [REM%] of the full 8-h sleep opportunity) did not significantly associate with the increase of daytime melatonin in the night shift protocol during those same 8 h (all P>0.34). To explore the temporal dynamics more closely, we also examined this relationship between the hourly sleep architecture and hourly melatonin levels during the daytime sleep. We found that melatonin increase during daytime sleep was negative associated with slow wave sleep (β=−1.5 ± 0.6%, P=0.02) in the same hour, while it tended to be positively associated with REM sleep (β=1.1 ± 0.6%, P=0.08); there was no significant association with the other sleep measures (all P>0.43).

Given that pineal melatonin production is under sympathetic control, we also examined the correlation between the daytime melatonin increase and urinary excretion of epinephrine and norepinephrine during the full 8-h daytime sleep episode. We did not detect any significant associations (all P>0.1).

Melatonin increase during daytime sleep was positively correlated with change in timing of nocturnal melatonin peak.

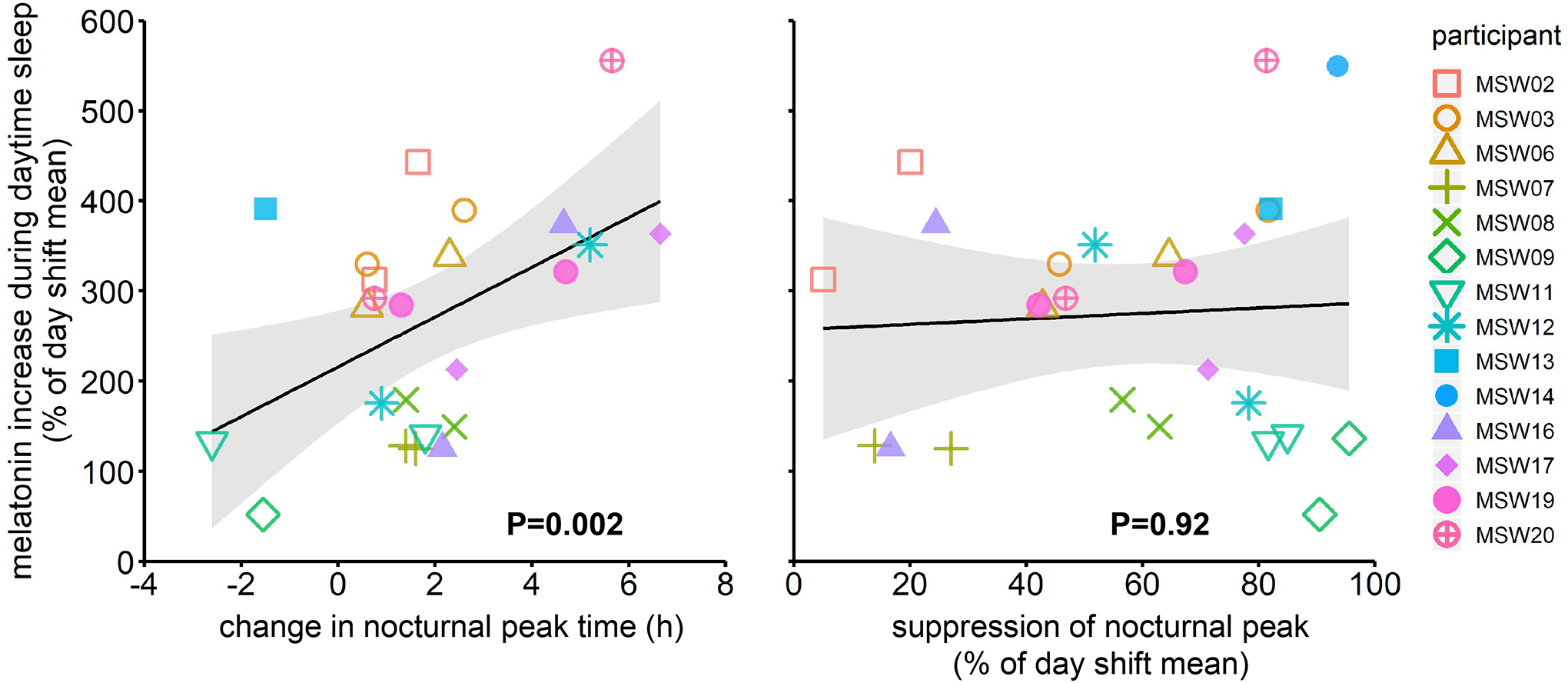

Since circadian synchronizers (e.g., light) can affect both the phase and amplitude of the central circadian pacemaker(s) that regulates the circadian rhythm in circulating melatonin concentrations, we examined the relationship between changes in the nighttime melatonin peak and daytime melatonin elevation. We found that the melatonin increase during daytime sleep was positively associated with the change in peak time (β=42.7 ± 10.0% per hour delay, P=0.002, Figure 4 left), but not with suppression of the nighttime melatonin peak (P=0.92, Figure 4 right; for correlations between the three melatonin measurements see Supplemental video). This association was independent of the quantity and quality of daytime sleep: including sleep parameters as covariates did not change the significance or substantially reduce the β coefficient of the association between change of melatonin peak timing and melatonin increase during daytime sleep (all P<0.05, β ranges from 36.8 to 37.1% per hour delay depending on whether including sleep as covariates).

Figure 4.

Melatonin increase during daytime sleep was positively correlated with change in time of nocturnal melatonin peak (left), but not with suppression of the nocturnal melatonin peak during wakefulness (right) during the simulated night shifts. Each individual is labeled with different colors and symbols. A linear regression line is shown in black with 95% confidence interval in grey. P values, statistical significance for adjusted association of melatonin increase during daytime sleep with change in peak time and suppression of peak.

Melatonin increase during daytime sleep was positively correlated with daily glucose and insulin AUC.

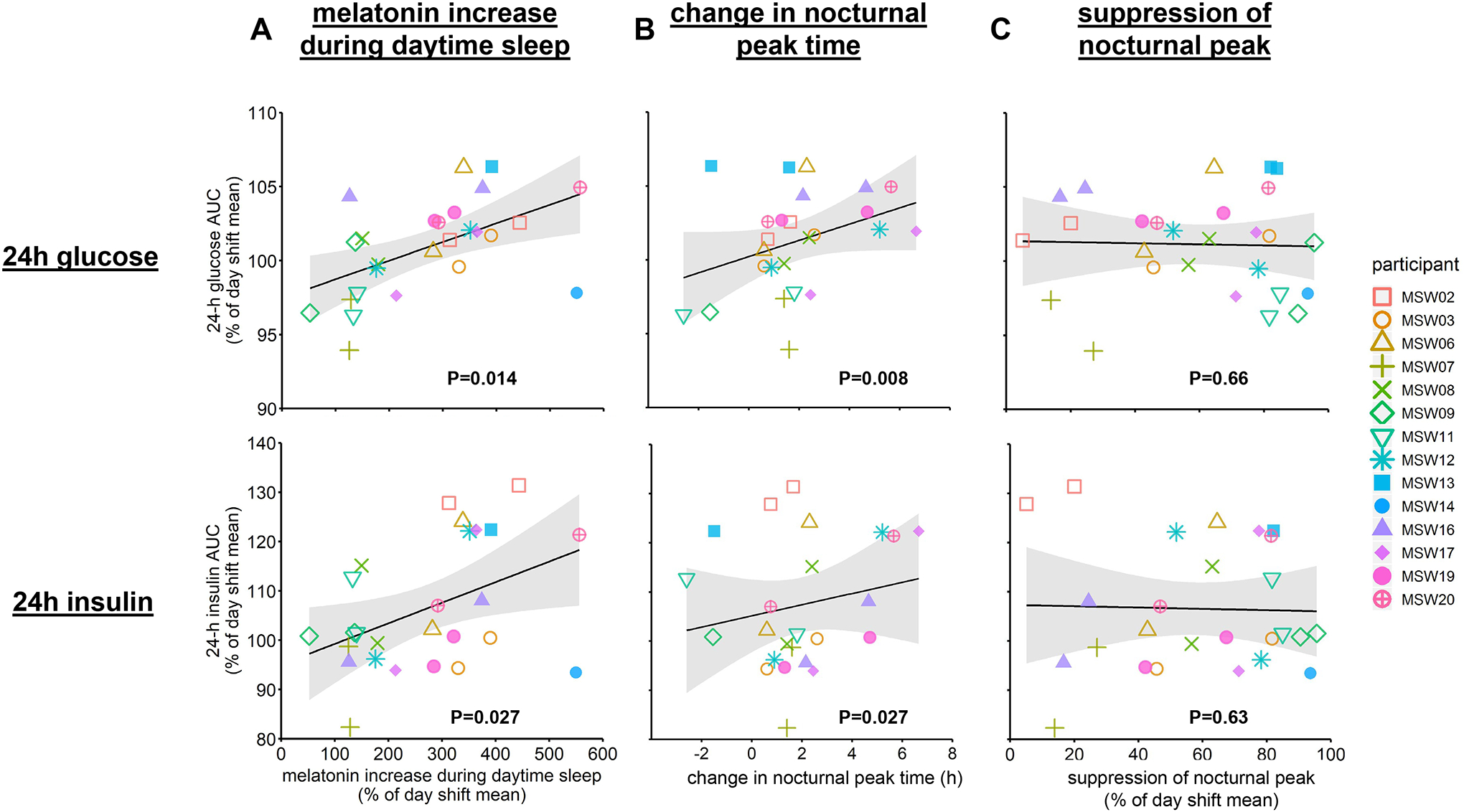

We tested whether interindividual differences in the melatonin response to the night shifts was associated with the adverse effects of circadian misalignment on glucose control. Under the night-shift condition, the percentage change of 24-h glucose AUC and 24-h insulin AUC from the day-shift condition were both positively correlated with melatonin increase during daytime sleep (β=1.2 ± 0.04% per 1-fold melatonin AUC increase, P=0.014 and β=4.7 ± 2.0% per 1-fold melatonin AUC increase, P=0.027, respectively; Figure 5A) with every 1-fold increase in daytime melatonin corresponding to a 1.2% increase in 24-h glucose AUC and a 4.7% increase in 24-h insulin AUC. The increased glucose despite increased insulin suggested that the relationship between daytime sleep melatonin and increased glucose levels may be partially mediated through decreased insulin sensitivity. These correlations remained significant after further adjustment for daytime sleep duration and/or sleep stages (all P<0.05), indicating that the correlations between melatonin increase during daytime sleep and glucose or insulin 24-h AUC were not simply explained by the quantity and quality of daytime sleep. The percentage change of 24-h glucose AUC and 24-h insulin AUC were also positively correlated with change in peak time (β=0.6 ± 0.2% per hour delay, P=0.008 and β=2.8 ± 1.1% per hour delay, P=0.027, respectively; Figure 5B). There was no significant correlation of 24-h glucose AUC or 24-h insulin AUC with suppression of the nocturnal melatonin peak (both P>0.60; Figure 5C).

Figure 5.

Relationships between changes in melatonin rhythm and changes in 24-h glucose (top) and insulin (bottom) AUC during simulated night shifts compared to day shifts. (A) Melatonin increase during daytime sleep was positively correlated 24-h glucose and insulin AUC. (B) Change in nocturnal melatonin peak timing was positively correlated with 24-h glucose AUC, but not with insulin AUC. (C) Suppression of nocturnal melatonin peak had no significant correlation with either 24-h glucose or insulin AUC. Each individual is labeled with different colors and symbols. Linear regression line is shown in black with 95% confidence interval in grey. P values, statistical significance for adjusted association between the changes in melatonin rhythm parameters and glucose/insulin measures.

DISCUSSION

Using a highly controlled simulated night-shift protocol with a rapid 12-hour inversion of sleep/wake schedules, we found that the 24-hour profile of circulating melatonin concentrations showed antiphasic daytime and nighttime peaks in the majority (~80%) of participants. Our findings of increases in circulating melatonin concentrations during daytime sleep in darkness challenge the currently accepted paradigm for the regulation of melatonin secretion. Based on current physiological and mathematical models, melatonin levels were expected to remain at very low, near-undetectable levels during the circadian day, even during darkness or sleep [12, 13, 33]. While it has long been recognized that light exposure suppresses melatonin during the circadian night, there was little prior evidence that exposure to darkness/sleep during the daytime could increase melatonin levels. Therefore, our results challenge this widely-held understanding, and suggest that atypical patterns may emerge in conditions with shifted sleep/wake and light/dark schedules.

Although rarely reported or emphasized, based on an extensive literature search, we found three examples that show some similarities with our reported daytime melatonin increase. One study reported a melatonin secretion pattern that included daytime melatonin secretion in patients with bipolar disorder during a manic episode [34]. However, this unconventional melatonin pattern may be due to neuropathological changes in the brain. The two other publications studied a healthy population. One of these latter two studies observed a significant increase in salivary melatonin in healthy young adults after taking a 30-min afternoon nap [35]. The second study in healthy adults observed a transient elevation in plasma melatonin levels in the afternoon (13:20–15:40) in 5 of the 16 profiles, coinciding with the acutely 8-h advanced sleep/dark episode [14]. While both studies made extra efforts to acknowledge the unusualness of the observed daytime melatonin rise, they only briefly mentioned the observation and did not find any plausible explanations. Importantly, neither reported repeated occurrence of daytime melatonin rise. Thus, the single observation could be a phase advance of melatonin rhythm, or a transient elevation by other factors. We not only observed repeated occurrence, but also a stronger daytime melatonin increase after repeated exposure (test day 3). Our observation indicates a potential circadian oscillatory property rather than a transient effect. Our data show a resemblance to the melatonin patterns with antiphasic peaks seen in hamsters exposed to LDLD 8:4:8:4, and in hamsters whose circadian activity rhythm splits into two bouts about 12 hours apart in response to a novel running wheel in darkness during the circadian day [36, 37]. Our observations based on an in-depth assessment of both between- and within-subject stability and variability of repeated 24-h circulatory melatonin profiles, including across 8-h daytime sleep episodes, and under highly-controlled conditions challenge the current understanding of the circadian regulation of melatonin in which melatonin production is thought to be restricted to the circadian night.

Remarkably, in the current study, more than half of the participants had the daytime melatonin increase occurring immediately after the transition day, with only exposure to dim light (~4 lux) in the interim day before the transition. This observation cannot readily be explained by light-induced phase shifting or amplitude suppression of SCN rhythms, since the phase-resetting effect of light exposure is intensity-dependent [38], the magnitude of phase shift is reduced to half maximum in typical room light (~100 lux as in the current protocol), and is much smaller for dim light (~4 lux) [3, 39]. While there are notable interindividual differences in light sensitivity for melatonin suppression [40], which we observed in response to the 90-lux condition, these differences cannot account for the changes in the melatonin profile observed under the dim light condition. Furthermore, in the current protocol, light exposure occurred in both during the phase delay and phase advance portion of the phase response curve. Importantly, the increases in plasma melatonin level during the daytime sleep episodes happened approximately 12 h separated from the primary peak during the circadian night. Taken together, these observations indicate that this secondary daytime peak was not part of the typical primary circadian nighttime peak in melatonin. Indeed, for some individuals, the melatonin increase during the daytime sleep episode was so distinct that, together with the nighttime peak, it formed a melatonin profile with two antiphasic peaks (e.g., MSW06).

A limit-cycle oscillator model was previously shown to successfully simulate the average effect of light on the melatonin rhythm [12, 32, 39], but it does not predict the daytime melatonin increase here. An alternative model, involving control of melatonin production by two phase-only oscillators, referred as E (evening) and M (morning) oscillators, was extensively investigated by Illnerova and Vanecek [41], following the classic work of Pittendrigh and Daan concerning splitting of circadian function into two components in different light conditions [42]. This two-oscillator model has been proposed to explain the splitting of nocturnal melatonin secretion in humans and sheep in response to changes in the duration of the photoperiod [43, 44]. However, these bimodal patterns of nocturnal melatonin secretion were composed of two melatonin peaks often at the onset and offset of the dark phase, and did not have a secondary peak in the middle of the day. In addition, the two-oscillator model requires over twenty cycles for the “splitting” rhythm to occur [45], which does not fit our abruptly appeared secondary daytime peak. Thus, this unexpected observation prompted us to examine potential mechanisms that may underlie the secondary daytime peak during sleep.

To understand the potential mechanism for the melatonin increase during daytime sleep, we first considered external behavioral and environmental factors that may affect circulating melatonin levels. First, according to decades of research on the circadian system and melatonin secretion, daytime exposure to darkness cannot stimulate melatonin secretion. Seminal animal studies have shown that acute exposure to darkness during the normal light period did not result in an acute increase in pineal melatonin level or N-acetyltransferase activity (the rate-limiting step in the biosynthesis of the circadian hormone melatonin) [5–7]. Human studies have also supported this notion, including those using the classical constant routine (CR) and forced desynchrony (FD) protocols which measured time-series of melatonin to estimate circadian phase and period (cycle length). These CR and FD protocols are typically conducted under constant very dim light condition (<4 lux, including <1 lux). However, to our knowledge, none have reported a melatonin rise during circadian daytime regardless being exposed to dim light (<4 lux) or moderate room light (100–200 lux), being awake (CR) or sleep (FD) [46–49]. Second, the change in physical activity is not likely to have caused the melatonin elevation during daytime sleep. The effect of physical activity on circulating melatonin concentration depends on circadian phase and activity intensity, with high-intensity exercise during nighttime consistently shown to stimulate melatonin secretion acutely [50, 51]. In our study, exercise was prohibited, and participants were limited to very low-level activities (e.g., reading a book, watching a video, slow walking, etc.). Moreover, the transition to inactivity during the sleep episode should have resulted in a decrease—if anything—in melatonin levels, not the increase we observed. Second, posture changes have been shown to affect melatonin levels, with an increase when changing from a supine to upright posture [52, 53]. This is opposite to what we found, where melatonin increased after participants changed from an upright to a supine posture to sleep. Third, there was no difference in the composition of the food between the baseline and shifted days that would obviously account for the change in melatonin levels (e.g., foods high in melatonin), and the timing of the melatonin rise did not match with the timing of the meals (the last meal was consumed 3h prior to onset of the scheduled sleep episode). Finally, we also did not find evidence from urinary catecholamine assays that changes in systemic activity of the sympathetic nervous system contributed to the daytime melatonin increase. However, future studies are needed to investigate this with more direct and higher temporal resolution measures, such as high-frequency blood sampling.

A plausible mechanism for our observations is a role for sleep in directly modulating melatonin production. Both sleep deprivation and sleep may influence plasma melatonin levels. Sleep deprivation has been reported to increase nocturnal melatonin levels during a constant routine as compared to melatonin levels during sleep on the prior baseline night [54] and during nighttime sleep when homeostatic sleep pressure was increased following a night of total sleep deprivation [55]. Probably most relevant to our current study, melatonin levels were also reportedly increased during daytime napping [35]. While none of these studies precisely replicate or account for our observation of daytime melatonin increase after mild sleep loss, they suggest that sleep itself, particularly following sleep deprivation, may indeed affect melatonin secretion, even during the daytime. A previous study in rodents found that slow-wave activity attenuates SCN neuronal activity in the circadian day, though melatonin was not measured in that study [18]. Given that decreased SCN electrical output may lead to attenuated GABAergic inhibitory signals to melatonin secretion[56], this finding suggests a mechanism by which slow-wave sleep might affect melatonin levels in humans, although effects may differ between nocturnal rodents and diurnal humans. On the other hand, the associations we found between daytime melatonin increase and sleep architecture could be driven by the opposite direction of effect: the effects of melatonin on sleep structure. However, it remains unclear how melatonin may affect sleep structure with prior studies reporting either no significant influences on slow-wave sleep and REM sleep [57, 58], or high dose melatonin increasing REM sleep [59]. Thus, future studies are needed to further investigate the relationship between daytime melatonin increase and sleep-wake state.

Interestingly, previous rodent studies have shown that desynchrony of the SCN subregions can be induced by changes in the light schedule, which may account for the distinct melatonin pattern with antiphasic daytime and nighttime peaks immediately after shifting the light-dark cycle by 12 h in our night shift protocol, although the light levels during wakefulness in this study were very dim (~4 lux). Notably, a circadian rhythm with two antiphasic peaks was reported in hamsters under conditions that involve prolonged light exposure during the circadian night, in which an animal’s single daily bout of wheel-running activity dissociated into two stable components about 12 hours apart. Previous studies have shown that this splitting of the behavioral rhythm is caused by a dissociation within the SCN, e.g., with the left and right SCN oscillating in antiphase, or the dorsal and ventral regions of the SCN oscillating in antiphase [60–62]. With a ‘splitting’ rhythm in wheel-running activity, the circadian rhythm of melatonin has also been shown to display two peaks [36, 37]. A sudden shift in the light-dark cycle can also disrupt synchronous oscillations in the SCN. A bimodal pattern in both electrical activity and clock gene expression has been found in SCN slices from rats subjected to a ≥6 hours phase delay or advance of the light-dark cycle [63, 64]. This might cause the inhibitory signal from the SCN to the pineal gland to become bimodal too, ultimately resulting in a melatonin pattern with two antiphasic peaks. The SCN also receives non-photic cues (e.g., rest/activity) [65]. Thus, if bimodal electrical-activity patterns in the SCN can be induced via shifted behavioral cycles, then this may account for why, in some participants, the melatonin increase during daytime sleep happened on test day 1 following only dim light exposure. Future studies are needed to test if other circadian measures (e.g., peripheral clock rhythms from fibroblasts, hair follicles or adipose samples) also acquire a secondary daytime peak under such conditions. On the other hand, previous animal and in vitro studies have shown that a less robust oscillations within the SCN permitted a larger phase shift, which may accelerate entrainment to an external resetting stimulus (e.g., light) [64, 66]. Thus, given the observed association between the melatonin increase during daytime sleep and shift in melatonin peak timing, future studies are needed to test whether a weak circadian oscillation in the SCN underlies the daytime melatonin increase.

Night-shift-induced circadian misalignment is known to adversely impact glucose metabolism, which may contribute to the increased risk of type 2 diabetes among night shift workers [21]. Here, we found that the melatonin increase during daytime sleep was positively associated with the increases in 24-h glucose and insulin levels in response to night-shift conditions. This suggests that the daytime melatonin increase that we observed may be associated with reduced insulin sensitivity. It has been shown that elevation of circulating melatonin concentration reduces glucose tolerance and insulin sensitivity in human [20, 67, 68]. However, the inhibitory effects of melatonin on glucose control shown in those studies occurred after a much larger increase in the melatonin level (>10 pg/mL [67, 69]); thus it is unknown whether a small increase in circulating daytime melatonin can impair glucose tolerance. Alternatively, as we suggested above, the daytime melatonin increase may reflect a less robust output of the central circadian pacemaker, which may result in weakened peripheral tissue entrainment [16, 70, 71]. In this case, under our night shift conditions, a different re-entrainment rate between central and peripheral oscillators may lead to internal desynchrony which has been proposed to compromise glucose control [72]. Whatever the underlying mechanism, this finding has potential practical implications. If an assessment of daytime melatonin expression can be used as an indirect assay of the metabolic impacts of night-shift work, then this could be an important tool for tracking health in shift workers.

Strengths of this study include the within-participant comparison, gold-standard sleep monitoring, and the highly controlled in-laboratory conditions which allowed us to minimize the potential influence from the behavioral and environmental factors. Limitations of the study include the relatively small sample size. Also, the study was not to designed to investigate the underly mechanisms of the melatonin rise during daytime sleep. However, our post-hoc analyses provide some mechanistic insights for future studies. Finally, it is possible that the observed daytime increase in reported melatonin concentrations is due to non-specificity of the assay. Although cross-reactivity is a concern for any radio-immunoassay (RIA), the BÜHLMANN Melatonin radioimmunoassay (Schönenbuch, Switzerland) used herein has a reported cross-reactivity of less than 0.03% with other similar structured compounds (e.g., 6-sulfatoxymelatonin, serotonin, N-acetylserotonin). Thus, it is very unlikely that the observed melatonin increase during daytime sleep represents cross-reactivity of the antibody with another compound.

In summary, in our simulated night-shift protocol, we observed an unexpected increase in melatonin during daytime sleep that was positively associated with the change in timing of the nighttime melatonin peak and the change in glucose and insulin levels (Figure 6). We hypothesize that SCN neuronal network properties or a direct effect of sleep-wake state may account for this unanticipated phenomenon. These findings could have implications for metabolic vulnerability to shift work. Continued investigation of the underlying mechanisms may provide novel insights into the organization of the human circadian system and facilitate the development of improved treatment for circadian rhythm disorders common in shift workers.

Figure 6.

Summary of the relationships among changes in daytime vs. nighttime melatonin, and changes in 24-h glucose and insulin levels in response to simulated night shift protocol as compared to the simulated day shift protocol in the current study.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

We thank the research volunteers and Brigham and Women’s Hospital’s CCI staff. This study was supported by NHLBI Grant R01 HL094806 to F.A.J.L.S., and by Clinical Translational Science Award UL1RR025758 to Harvard University and Brigham and Women’s Hospital from the National Center for Research Resources. J.Q. was funded in part by R01 DK102696 and K99 HL145800. F.A.J.L.S. was funded in part by R01 HL094806, R01 HL118601, R01 DK099512, R01 DK102696, R01 DK105072. K.H. and P.L. were funded in part by RF1AG059867 and RF1AG064312. P.L. was also funded by the BrightFocus Foundation A2020886S.

Footnotes

Declaration of Interests. JQ, PL, WW, KH, and JA declare no conflicts of interest. Please see other authors’ conflicts of interest in Appendix.

REFERENCE

- 1.Kalsbeek A, et al. , Melatonin sees the light: blocking GABA-ergic transmission in the paraventricular nucleus induces daytime secretion of melatonin. Eur J Neurosci, 2000. 12(9): p. 3146–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Perreau-Lenz S, et al. , Suprachiasmatic control of melatonin synthesis in rats: inhibitory and stimulatory mechanisms. Eur J Neurosci, 2003. 17(2): p. 221–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zeitzer JM, et al. , Sensitivity of the human circadian pacemaker to nocturnal light: melatonin phase resetting and suppression. J Physiol, 2000. 526 Pt 3: p. 695–702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jewett ME, Kronauer RE, and Czeisler CA, Light-induced suppression of endogenous circadian amplitude in humans. Nature, 1991. 350(6313): p. 59–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reppert SM, et al. , The effects of environmental lighting on the daily melatonin rhythm in primate cerebrospinal fluid. Brain Res, 1981. 223(2): p. 313–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tamarkin L, et al. , Studies on the daily pattern of pineal melatonin in the Syrian hamster. Endocrinology, 1980. 107(5): p. 1525–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Binkley SA, Klein DC, and Weller JL, Dark induced increase in pineal serotonin N-acetyltransferase activity: a refractory period. Experientia, 1973. 29(11): p. 1339–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lynch HJ, et al. , Entrainment of rhythmic melatonin secretion in man to a 12-hour phase shift in the light/dark cycle. Life Sci, 1978. 23(15): p. 1557–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Czeisler CA, et al. , Bright light induction of strong (type 0) resetting of the human circadian pacemaker. Science, 1989. 244(4910): p. 1328–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brown EN, et al. , A mathematical model of diurnal variations in human plasma melatonin levels. Am J Physiol, 1997. 272(3 Pt 1): p. E506–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Klerman EB, et al. , Comparisons of the variability of three markers of the human circadian pacemaker. J Biol Rhythms, 2002. 17(2): p. 181–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.St Hilaire MA, et al. , A physiologically based mathematical model of melatonin including ocular light suppression and interactions with the circadian pacemaker. J Pineal Res, 2007. 43(3): p. 294–304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Breslow ER, et al. , A mathematical model of the circadian phase-shifting effects of exogenous melatonin. J Biol Rhythms, 2013. 28(1): p. 79–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Van Cauter E, et al. , Rapid phase advance of the 24-h melatonin profile in response to afternoon dark exposure. Am J Physiol, 1998. 275(1): p. E48–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wiesner CD, et al. , Melatonin Secretion during a Short Nap Fosters Subsequent Feedback Learning. Front Hum Neurosci, 2018. 11: p. 648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abraham U, et al. , Coupling governs entrainment range of circadian clocks. Mol Syst Biol, 2010. 6: p. 438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bernard S, et al. , Synchronization-induced rhythmicity of circadian oscillators in the suprachiasmatic nucleus. PLoS Comput Biol, 2007. 3(4): p. e68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Deboer T, et al. , Sleep states alter activity of suprachiasmatic nucleus neurons. Nat Neurosci, 2003. 6(10): p. 1086–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arendt J, Mammalian pineal rhythms. Pineal Res Rev, 1985. 3: p. 161–213. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Garaulet M, et al. , Melatonin Effects on Glucose Metabolism: Time To Unlock the Controversy. Trends Endocrinol Metab, 2020. 31(3): p. 192–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mason IC, et al. , Impact of circadian disruption on glucose metabolism: implications for type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia, 2020. 63(3): p. 462–472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morris CJ, et al. , Circadian misalignment increases cardiovascular disease risk factors in humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2016. 113(10): p. E1402–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morris CJ, et al. , Endogenous circadian system and circadian misalignment impact glucose tolerance via separate mechanisms in humans. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2015. 112(17): p. E2225–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tucker MA, et al. , The Relative Impact of Sleep and Circadian Drive on Motor Skill Acquisition and Memory Consolidation. Sleep, 2017. 40(4). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chellappa SL, Morris CJ, and Scheer F, Daily circadian misalignment impairs human cognitive performance task-dependently. Sci Rep, 2018. 8(1): p. 3041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li P, et al. , Reduced Tolerance to Night Shift in Chronic Shift Workers: Insight From Fractal Regulation. Sleep, 2017. 40(7). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chellappa SL, Morris CJ, and Scheer F, Circadian misalignment increases mood vulnerability in simulated shift work. Sci Rep, 2020. 10(1): p. 18614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Morris CJ, et al. , Endogenous circadian system and circadian misalignment impact glucose tolerance via separate mechanisms in humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2015. 112(17): p. E2225–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Qian J, et al. , Differential effects of the circadian system and circadian misalignment on insulin sensitivity and insulin secretion in humans. Diabetes Obes Metab, 2018. 20(10): p. 2481–2485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Qian J, et al. , Ghrelin is impacted by the endogenous circadian system and by circadian misalignment in humans. Int J Obes (Lond), 2019. 43(8): p. 1644–1649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Qian J, et al. , Sex differences in the circadian misalignment effects on energy regulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2019. 116(47): p. 23806–23812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jewett ME, Forger DB, and Kronauer RE, Revised limit cycle oscillator model of human circadian pacemaker. J Biol Rhythms, 1999. 14(6): p. 493–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Abeysuriya RG, et al. , A unified model of melatonin, 6-sulfatoxymelatonin, and sleep dynamics. J Pineal Res, 2018. 64(4): p. e12474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Novakova M, et al. , The circadian system of patients with bipolar disorder differs in episodes of mania and depression. Bipolar Disord, 2015. 17(3): p. 303–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wiesner CD, et al. , Melatonin Secretion during a Short Nap Fosters Subsequent Feedback Learning. Front Hum Neurosci, 2017. 11: p. 648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Raiewski EE, et al. , Twice daily melatonin peaks in Siberian but not Syrian hamsters under 24 h light:dark:light:dark cycles. Chronobiol Int, 2012. 29(9): p. 1206–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gorman MR, Yellon SM, and Lee TM, Temporal reorganization of the suprachiasmatic nuclei in hamsters with split circadian rhythms. J Biol Rhythms, 2001. 16(6): p. 552–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Boivin DB, et al. , Dose-response relationships for resetting of human circadian clock by light. Nature, 1996. 379(6565): p. 540–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jewett ME and Kronauer RE, Refinement of a limit cycle oscillator model of the effects of light on the human circadian pacemaker. J Theor Biol, 1998. 192(4): p. 455–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Phillips AJK, et al. , High sensitivity and interindividual variability in the response of the human circadian system to evening light. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2019. 116(24): p. 12019–12024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Illnerová H and Vaněček J, Two-oscillator structure of the pacemaker controlling the circadian rhythm of N-acetyltransferase in the rat pineal gland. Journal of comparative physiology, 1982. 145(4): p. 539–548. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pittendrigh CS and Daan S, A functional analysis of circadian pacemakers in nocturnal rodents. Journal of Comparative Physiology ? A, 1976. 106(3): p. 333–355. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wehr TA, et al. , Bimodal patterns of human melatonin secretion consistent with a two-oscillator model of regulation. Neurosci Lett, 1995. 194(1–2): p. 105–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Arendt J, Symons AM, and Laud C, Pineal function in the sheep: evidence for a possible mechanism mediating seasonal reproductive activity. Experientia, 1981. 37(6): p. 584–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Daan S and Berde C, Two coupled oscillators: simulations of the circadian pacemaker in mammalian activity rhythms. J Theor Biol, 1978. 70(3): p. 297–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Santhi N, et al. , Sex differences in the circadian regulation of sleep and waking cognition in humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2016. 113(19): p. E2730–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Smith KA, Schoen MW, and Czeisler CA, Adaptation of human pineal melatonin suppression by recent photic history. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 2004. 89(7): p. 3610–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dijk DJ, et al. , Ageing and the circadian and homeostatic regulation of human sleep during forced desynchrony of rest, melatonin and temperature rhythms. J Physiol, 1999. 516 (Pt 2): p. 611–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wehrens SMT, et al. , Meal Timing Regulates the Human Circadian System. Curr Biol, 2017. 27(12): p. 1768–1775 e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Buxton OM, et al. , Exercise elicits phase shifts and acute alterations of melatonin that vary with circadian phase. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol, 2003. 284(3): p. R714–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Atkinson G, et al. , The relevance of melatonin to sports medicine and science. Sports Med, 2003. 33(11): p. 809–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Deacon S and Arendt J, Posture influences melatonin concentrations in plasma and saliva in humans. Neurosci Lett, 1994. 167(1–2): p. 191–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nathan PJ, et al. , Modulation of plasma melatonin concentrations by changes in posture. J Pineal Res, 1998. 24(4): p. 219–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zeitzer JM, et al. , Plasma melatonin rhythms in young and older humans during sleep, sleep deprivation, and wake. Sleep, 2007. 30(11): p. 1437–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Salin-Pascual RJ, et al. , The effect of total sleep deprivation on plasma melatonin and cortisol in healthy human volunteers. Sleep, 1988. 11(4): p. 362–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Welsh DK, Takahashi JS, and Kay SA, Suprachiasmatic nucleus: cell autonomy and network properties. Annu Rev Physiol, 2010. 72: p. 551–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wyatt JK, et al. , Sleep-facilitating effect of exogenous melatonin in healthy young men and women is circadian-phase dependent. Sleep, 2006. 29(5): p. 609–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Arbon EL, Knurowska M, and Dijk DJ, Randomised clinical trial of the effects of prolonged-release melatonin, temazepam and zolpidem on slow-wave activity during sleep in healthy people. J Psychopharmacol, 2015. 29(7): p. 764–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dijk DJ and Cajochen C, Melatonin and the circadian regulation of sleep initiation, consolidation, structure, and the sleep EEG. J Biol Rhythms, 1997. 12(6): p. 627–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tavakoli-Nezhad M and Schwartz WJ, c-Fos expression in the brains of behaviorally “split” hamsters in constant light: calling attention to a dorsolateral region of the suprachiasmatic nucleus and the medial division of the lateral habenula. J Biol Rhythms, 2005. 20(5): p. 419–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.de la Iglesia HO, et al. , Antiphase oscillation of the left and right suprachiasmatic nuclei. Science, 2000. 290(5492): p. 799–801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yan L, et al. , Two antiphase oscillations occur in each suprachiasmatic nucleus of behaviorally split hamsters. J Neurosci, 2005. 25(39): p. 9017–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nagano M, et al. , An abrupt shift in the day/night cycle causes desynchrony in the mammalian circadian center. J Neurosci, 2003. 23(14): p. 6141–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Albus H, et al. , A GABAergic mechanism is necessary for coupling dissociable ventral and dorsal regional oscillators within the circadian clock. Curr Biol, 2005. 15(10): p. 886–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Edgar DM, Reid MS, and Dement WC, Serotonergic afferents mediate activity-dependent entrainment of the mouse circadian clock. Am J Physiol, 1997. 273(1 Pt 2): p. R265–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.An S, et al. , A neuropeptide speeds circadian entrainment by reducing intercellular synchrony. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2013. 110(46): p. E4355–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Rubio-Sastre P, et al. , Acute melatonin administration in humans impairs glucose tolerance in both the morning and evening. Sleep, 2014. 37(10): p. 1715–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Cagnacci A, et al. , Influence of melatonin administration on glucose tolerance and insulin sensitivity of postmenopausal women. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf), 2001. 54(3): p. 339–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lopez-Minguez J, et al. , Late dinner impairs glucose tolerance in MTNR1B risk allele carriers: A randomized, cross-over study. Clin Nutr, 2018. 37(4): p. 1133–1140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sellix MT, et al. , Aging differentially affects the re-entrainment response of central and peripheral circadian oscillators. J Neurosci, 2012. 32(46): p. 16193–202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Mohawk JA and Takahashi JS, Cell autonomy and synchrony of suprachiasmatic nucleus circadian oscillators. Trends Neurosci, 2011. 34(7): p. 349–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Qian J and Scheer F, Circadian System and Glucose Metabolism: Implications for Physiology and Disease. Trends Endocrinol Metab, 2016. 27(5): p. 282–293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.